Dianne Jacob's Blog, page 4

April 27, 2021

How to Avoid Cultural Appropriation in Food Writing

A guest post by Nandita Godbole

A guest post by Nandita Godbole

Recipe writers and content creators frequently struggle to understand cultural appropriation. To some, cultural appropriation challenges the old ways of doing things. Others wonder why food writers lose their jobs over it. They question why it is important. Is it?

Here’s my understanding of cultural appropriation and how to avoid it as a food writer: 1. First of all, what is cultural appropriation?Wikipedia describes cultural appropriation as “The adoption of an element or elements of one culture or identity by members of another culture or identity.” For me, it also means profiting from another culture without compensating them adequately.

In the food space, cultural appropriation shows up in products, as repackaged ingredients, in cookbooks, and in recipes. The most problematic scenarios emerge when people outside the culture use an item for their own profit. Cultural appropriation can create an elitist environment and approach to world cuisines. It assumes that the cultural legacies of under-represented or historically marginalized cultures and people are available for profit.

2. How does it start, and how does it go horribly wrong?Most civic-minded adults do not intentionally seek to harm or misrepresent another persons’ culture or cuisine. But sometimes, writers channel the innocent appreciation of other cultures into a commodity that only benefits themselves. Such commodification typically eliminates all mentions of the origins of that food culture. It also eliminates the communities who consume the foods every day. And it ignores the place of that food in the culinary history of that culture, or mentions all of it in passing.

One famous instance occurred when two American women tried to pass off classic Mexican recipes as their own to start a business. Jaime Olivers’ interpretation of jerk rice proved problematic because of who made it versus the dish’s origins. People also objected to the ingredients of the dish as prepared by Jamaicans versus what he prepared for his audience. Oliver’s glaringly incomplete knowledge of the dish insulted Jamaicans, who consume jerk dishes every day. While Oliver tried to highlight his creativity, his “inspiration” was poised to profit from a historically underrepresented community that often is undervalued and underpaid.

In each case, none of the individuals or companies had any direct ethnic or cultural ties to the commodity they promoted under their own brand name.

In this Eater piece, Navneet Alang discuss the aftermath of the Alison Roman controversy. Alang notes that most successful folks are successful because they have worked very hard. But, despite their best intentions, the thrill of success can sometimes trigger cultural appropriation. When successful people do not recognize the inequities in the business, or become part of perpetuating inequities, they are part of the problem.

3. Can people cook dishes from another culture?Yes. We can cook anything we like. But if we are teaching someone else (in the family or for commerce) there are ways to do it respectfully:

When cooking for yourself or your family, learn about that culture’s foodsIf you must promote another culture’s dish for commerce, include several ways your audience can learn more about that cuisine and dish from a different source or expert from that cuisineSocial media posts are particularly notorious for blurring the lines. Making a dish for fun is one thing. If you do not include information about your inspiration for the dish, it risks being called out as cultural appropriation.4. How to cook from, write about, or teach someone else a dish from your own heritage.This topic deals with at least three issues: ownership, lived experience, and communication, all negotiated through access to resources and the guidance of a teacher. When you are writing about your heritage, you are often navigating a grey area.

Regardless of your proximity to a culture, when writing or developing a recipe for a blog, a cookbook, or an article, treat it as a research paper. Identify all your sources and inspirations, especially if the dish is heavily inspired by something or someone other than yourself. Include how you are connected to the dish. If family or friends taught you a dish, include them in the headnote. Readers want to know how our experiences fit into the story of that dish.

Here’s another thing to consider: What makes you an expert to write about it? If it relies on access to the editor’s desk, share the spotlight those who know the topic better than you.

No one is born with all the knowledge, or can fully claim to being an expert. Yet, we all have our place in telling the story of a dish. While we teach those who come after us, there are more who came before who taught us.

Reflect the interchangeable roles of teacher and student. If you felt inspired by the work of a fellow writer or a published author, recognize that that work that came before your own. Even small but meaningful gestures can show respect.

In closingNo matter the platform or medium of audience engagement, if you show someone how to make a dish, you take on the role of a teacher. A good teacher encourages thoughtful inquiry and encourages students to be respectful of the food and culture they learn about.

Writers must continually inspire mutual respect. A cuisine or its people are never a curiosity, a theme, or an invitation to commodify. A cuisine tells the story of humans living, thriving, and nourishing other humans. Good writers, like good journalists, tell the complete human stories in the best way they can, because those stories will always matter more than the byline.

* * *

Nandita Godbole is an Atlanta-based, Indian origin, indie author of many cookbooks, including her latest, “Seven Pots of Tea: an Ayurvedic approach to sips and nosh.” Her work has appeared on Healthline, Forbes, NBC-Asian America, CNN, BBC-Futures, Thrillist, Epicurious. As @currycravings on social media, she shares simple ways to make classic Indian recipes. She also talks about chai and the bounty of her unruly garden.

( Photo courtesy of Julian Hochgesang-Huep on Unsplash.)

The post How to Avoid Cultural Appropriation in Food Writing appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

April 13, 2021

Win a New Edition of Will Write for Food!

I’m excited to announce that the fourth edition of Will Write for Food: Pursue Your Passion and Bring Home the Dough Writing Recipes, Cookbooks, Blogs, and More is available for pre-order. It will publish on May 25, 2021.

I’m excited to announce that the fourth edition of Will Write for Food: Pursue Your Passion and Bring Home the Dough Writing Recipes, Cookbooks, Blogs, and More is available for pre-order. It will publish on May 25, 2021.

And you should definitely win a copy from me. Just leave a comment below.

Can you believe that I’ve written four editions of this book? Sometimes I want to pinch myself. Especially since they have sold a collective 55,000 copies since debuting in 2005.

Maybe you have read or owned a previous edition. Here’s what they look like, to jog your memory:

The first edition debuted in 2005. I was only supposed to write 80,000 words, but I got carried away and wrote 120,000, all in four months! The editor liked it all and kept it. It has stayed the same size ever since. If you’re old enough to remember the cover of The Man Who Ate Everything, an enormously successful book of essays by Jeffrey Steingarten, we riffed on its design for our own version. And I loved the nod to my old journalism days, where I typed stories on a typewriter, not a computer.

The second edition published five years later, in 2010. I thought the cover was a little feminine. Some people said they thought it was a memoir. I ditched the chapter on writing fiction and wrote a long new chapter about this thing called food blogging. Lifelong Books/Perseus bought Marlowe & Company, so that meant a new editor and publisher. Luckily for me, Renee Sedliar became the editor of this and the future editions.

The third edition published in 2015. I thought this cover was very strong. I wanted a pen instead of one of the cooking utensils, but lost that battle. Notice that “Restaurant Reviews” disappeared from the subtitle list. Few people want to go in that direction these days. With Yelp on the scene, there is little call for criticism.

So you’re probably wondering what’s new in this edition of Will Write for Food. A few things:1. There’s a new chapter on voice.These days so many food writers cover the same topics, so how do you stand out? With a strong, distinguishable voice. Voice also comes through in your photography, and I give some examples.

2. I’ve kept the expert advice from names you recognize, and added new people.They talk about best practices for freelancers, critics, and bloggers, including:

Priya Krishna, now a reporter for the food section of the New York TimesSoleil Ho, restaurant reviewer of the San Francisco ChronicleChandra Ram, editor of Plate magazineNamiko Hirasawa Chen, food blogger of the mega blog Just One CookbookMaggie Zhu, food blogger at Omnivore’s Cookbook.3. There’s more about how to make money as a blogger.Big bloggers tell me that the people who ask them for advice want to make money. As a result I’ve expanded the chapter on Bringing Home the Bacon, with more inside information on how they and others make the big bucks.

4. I expanded the section on self publishing.I’ve found that, when I teach about how to become traditionally published, many people realize that the way to go is to self publish. I’ve expanded the section and resources for where to find publishers, designers, and printers.

5. There’s more about social media.I’m constantly surprised by how many people want to write a cookbook but can’t bring themselves to do social media. I hope to convince them that there’s a way forward that they can actually enjoy. Social media has become such a big, indispensable part of what we do. And pretty much inevitable. So I concentrate on how to build bigger platforms and how to accept your love/hate relationship with it.

Overall, I’ve tried to update everything, to make it as current as possible. There are chapters on how to get published, how to write recipes, how to come up with a cookbook, get better freelance assignments, start and continue a blog, review restaurants and write personal essays and memoir.

Food writing has never been so popular, in a nation obsessed with food. I hope that if you’ve read prior editions and found them useful, you’ll help me get the word out about this update. If you’d like to buy a copy, please purchase Will Write for Food from your favorite independent bookseller. They need your support more than Jeff Bezos. I use Amazon daily for research but prefer to purchase books from an independent.

I hope to see you in one of my upcoming events. I”m excited abut a June in person event at Omnivore Books in San Francisco— the first live events since the pandemic began. Otherwise, please subscribe to my free food writing newsletter, if you haven’t already, to see what’s on the calendar.

Enter to win your copy!Now, if you’d like to win a copy of the fourth edition of Will Write for Food, please leave a comment below. I will pick a winner at random by May 1, 2021. This offer applies to residents of the US only.

(Disclosure: This post contains an affiliate link.)

The post Win a New Edition of Will Write for Food! appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

March 30, 2021

7 Tips for Making a Cookbook — and Keeping Your Sanity

By Jennifer Kurdyla and Abbey Rodriguez

By Jennifer Kurdyla and Abbey Rodriguez

Do you dream of turning your blog (or collection of index cards) into a cookbook? Or maybe you already have a publishing deal in place? Regardless, so much goes into making a cookbook that you won’t see in the finished product. But like recipes themselves, there are ways to make the process easier.

The two of us spent 2020 creating Root & Nourish, our new cookbook focused on herbalism for women’s health. The pandemic threw us some major curveballs, but even in normal times, making a cookbook reveals lots of gaps in preparation, knowledge, and experience.

Here are some of the things we wish we knew when we made Root & Nourish: 1. Your book is not your blog.As a blogger, you may have an audience/food niche/tone already established and beloved by your readers. Keep this in mind as you develop your ideas and start writing. But also feel free to explore something different. We both had our own blogs, with overlapping but different focuses. The book became a hybrid of the two. It also introduced concepts and a cohesive narrative about food and cooking that neither of us had deliberately focused on thus far.

There’s also key distinctions in the style of blogs versus books. As a general rule, the headnotes in books are much shorter than those on blogs (with less personal story and less SEO). Books also need introductory writing to explain what the book is about. The whole book has to tell a story, and your recipes must contribute to that story in a cohesive way.

If you’re working with a publisher, they’ll likely want input on the writing and photography, so keep in mind that the creation process will be more collaborative than a solo blog. If you’re taking your own photos, keep them clean and classic, rather than optimized for Pinterest. Avoid overly trendy backgrounds, props, or styling. Think about how the images can serve as part of the instruction and how they will look together, in terms of the book’s overall layout and composition.

2. You’ll need a task list and timeline.When you’re about to cook, you make sure you have the ingredients you need, and maybe prepare a mise en place. The same goes for writing a book. You need to prep to make it all come together at the end (literally and metaphorically!).

Here’s a test of one of our homemade photo backdrops. Abbey chose hues of pink, white, and grey paint that helped unify the photos throughout. We sent these “swatches” to our design team. They advised us which backgrounds to pair with which dish, and guided the other design elements of the book.

We used Google Drive to make folders, and spreadsheets and shared docs for different stages of the process. We built in deadlines for rest and to celebrate meeting a goal (which is very much a part of what’s in the book). Our process reflected our practice in that way. Here are the tasks we considered:

Proposal developmentAgent searchingPublisher searchingManuscript development Recipe testingPhoto shoot planning and executing (including making the food)Manuscript editing Marketing and publicity.3. Make a book budget — and double it.We were so excited to start working with a publisher for a number of reasons, including because they gave us money up front (called an advance) to do our work. But publishing budgets rarely line up with reality, so we did some math to see if we could make a profit.

Preparing a budget helps establish clear expectations for the resources you’ll need to write, cook and photograph your book. Consider:

the cost of groceriestime to make the food, write about it, and to do the other writing for the book and the marketing and mailing costs that might be extraneous to what the publisher will contribute.You’ll probably need to make some dishes a few times, which multiplies how much time and money each costs. So look at the numbers you crunch initially, then double them, and you might find yourself close to breaking even at the end.

Depending on your financial and life situation, you may need to make adjustments to other sources of income, childcare, or even where you are living. Jennifer did her recipe development from a tiny New York kitchen with only one saute pan, a one-quart sauce pan, baking sheets, and one Dutch oven. Abbey made her recipes and styled photos while taking care of (and home-schooling) three kids. The pandemic definitely complicated some of our plans, even the ones with lots of wiggle room. Planning for more time, money, and space is always the side to err on.

4. Recruit friends who like to eat.

One of the things we were most excited about for the book-making process was recipe testing. We envisioned tasting parties with friends, family, and neighbors, where people would gather around a big table and comment on myriad versions of the same dish, giving feedback on which one tasted best. The pandemic changed all that, but we still relied on a number of people to offer this valuable information—and help us make sure our leftovers didn’t go to waste.

Inviting people into our process during quarantine was even more important, since it served as a way to connect. Delivering meals and having people make things themselves at home created much-needed diversions and excuses to reach out to people and talk about things other than the news. Even in non-pandemic conditions, testing and getting other people’s opinions—who have different tastes and cooking experience—ensures your cookbook is accessible and enjoyable for your readers. We wound up making all of our recipes at least twice, including once during the photo shoot, which was not necessarily the best time to realize a recipe needed tweaking.

5. Storyboard your photo shoot ahead of time.

Here’s Abbey setting up her camera for an overhead shot. We worked in very real-life conditions, shooting in her home with changing light conditions. It required some fancy equipment (including daredevil ladder balancing!). Planning out which dishes we needed for this set-up was so helpful. We shot many in a row and avoid having to recreate these specific camera heights and angles.

If you have a blog and take your own photos, you know that hours go into every shot you post. Maybe you have a set routine, like batch cooking and shooting one day, then writing another, or maybe you do a whole post from start to finish to stay in the same headspace.

Either way, the scale of a cookbook shoot is bigger than even the most intricate blog post. You’ll make and shoot dozens of recipes, and depending on where you’re shooting (whether at home or in a studio), who’s helping you, and your budget and timeline, the process might take place over weeks, or even months.

Look at your schedule, consider any seasonal ingredients, and make a storyboard for your photos ahead of time to help the process go more smoothly. Consider which parts of the dish are important to show. Is there a special technique, ingredient, or mood you want to highlight? Sketch them out and put them all in order so you can evaluate the flow of the photos. You won’t want all the same style shots next to each other. We also shared inspiration photos from blogs and magazines with our art directors ahead of time, so they could weigh in on the photo story.

Then, plan to take groups of photos with the same set-up, props, or ingredients, so you don’t have to switch out so many things for every shot. (This likely won’t be the order the photos will go in for the book.)

The pandemic prevented us from doing the week-long photo-fest we originally planned. We were only able to get together to shoot in the same space for two days. Having that plan in place was crucial for when Abbey, who (wo)manned the camera, and had to finish the other half of the photos solo.

6. Get a kitchen assistant.

We made all of the dishes in the book fresh for the photo shoot. Despite our extensive plans, we weren’t expecting to be so exhausted by the end of the first two days. No doubt part of that fatigue came from prepping the dishes, styling them, shooting them, and cleaning up all at the same time. Our four hands could only do so much!

While we did have some generous lighting help from Abbey’s sons, having another cook in the kitchen would have been very helpful. You could hire a stranger or recruit a foodie friend to keep the recipes coming out hot. It’s definitely worth the investment. Remember: payment in food could be a reasonable option.

7. Think beyond the book.Holding our finished books in our hands was one of the best moments of our lives. All our hard work was finally here, in this tangible thing other people would soon buy and enjoy. But realistically, we don’t expect to be living off royalties of Root & Nourish. And at heart, we are teachers who want to make the ideas we put in our book something people incorporate into their daily lives, as we have.

So we’re imagining different kinds of media, resources, events, classes, and products. They might give the book a life outside of the binding. They could offer ways to continually bring new people to the book. And they will help us grow as cooks and writers. Showing how people really respond to the recipes and giving feedback can inspire us on where to go next.

Just like with cooking, the best part of any meal is sharing it. Finding creative ways to repurpose your book’s ethos will serve the long-term benefit of your book sales, business, and creativity.

* * *

Jennifer Kurdyla and Abbey Rodriguez are co-authors of Root & Nourish: An Herbal Cookbook for Women’s Wellness (Tiller Press, 2021). Jennifer is an Ayurvedic health counselor, yoga teacher, and writer. Plant-based since 2008, she lives in Brooklyn, New York. Read more at www.benourished.me and follow her on Instagram @jenniferkurdyla. Abbey Rodriguez is a certified holistic nutritionist, herbalist, and food content creator. Since 2015, she has developed recipes for women and young families on her food and wellness blog, The Butter Half. She lives in Northern Virginia with her husband and three children. Visit her on Instagram @thebutterhalf.

The post 7 Tips for Making a Cookbook — and Keeping Your Sanity appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

March 16, 2021

Tons of Tips to Improve Your Food Styling

By Pascale Beale

By Pascale Beale

Food photography and styling is all about seduction. When someone looks at your image, you want them to think, “That looks so good, I want to eat that, now!” So, before taking a photo, think about two key elements that will improve your food styling:

Which medium is the image for? This will dictate the shape, style and composition. Instagram works best with square shots, which would impact your styling choices, for example.What story is the shot telling us? Your choice of background, props and plating style will help to tell that story. A shot of a dish cooked outdoors requires a different set of props and styling than a photo of a dessert.Once you establish the key elements, here’s how to improve your food styling for blogs, social media and cookbooks:1. Pick one: natural or artificial light.Good lighting is the most fundamental part of food photography. It literally shapes the food. You can have the most beautifully plated food, but if the light is wrong, the dish will look flat and unappetizing. Shoot with either natural (my preferred choice) or artificial light. You cannot use both.

I shot this salad (used as the cover of my cookbook, Salade II) with indirect natural light, which accented the different textures of the white elements — cheese, platter, and servers — in the dish.

As acclaimed food photographer Eva Kosmas Floras says:

“Never mix two different color temperatures in the same photograph (i.e., artificial + natural light). You will end up with blue or orange parts of the image, or both, and it will have a very strange effect on the final photograph.

“If shooting in natural light, (it) has different color temperatures depending on the time of day, ranging from blue to yellow/orange. Blue light invokes freshness, yellow light suffuses images with comfort. Achieving a white balance, where white looks white, is key to making the food look as natural as possible on the plate.”

(For more information on color temperature, see the post Understanding color temperature and read Art of Light by Rachel Korinek.)

Either light source creates shadows across the dish. Use shadow to add texture, dimension, form and depth. Shadow also helps you tell a story. A bright and diffused background evokes lunchtime or a summer’s day. It complements light foods such as salads or chilled soups. Lengthy dark shadows evoke the feeling of an evening meal, and complement heartier fare such as stews and roasts.

2. Find the focal point of your photo.In an art class in eighth grade, I learned about the rule of thirds, a rule that has served me to this day with food styling. It advises that you break any image into a grid with two horizontal and two vertical lines, forming nine equally proportioned areas. Place the key elements either on the lines or where they intersect. The resulting composition draws the viewer’s eye across the scene and to the focal point, the dish you showcase.

All the elements in this image draw the eye to the radishes in the middle of the shot.

Negative space and offset framing help create an interesting background for your food and can improve your food styling. A bowl of soup placed so that only half can be seen, but with some key ingredients scattered around the dish, create a more dynamic shot than a bowl centered in the frame.

Many photographers love overhead shots. They can be effective and attractive when shooting a whole tablescape of multiple dishes — a mezze feast, for example, or capturing the geometric pattern made by pastries cooling on a wire rack. But overhead shots don’t work for every dish. They would not show a soufflé to its best advantage, for example.

3. Tell a story.This is about ambiance and mood. Hands cupping a steaming bowl of soup, or pulling out a slice of cheesy pizza from a pizza box immediately convey a story. The first shows a dish that is cozy and warm, and the second shows a dish you can’t wait to dive into. Similarly, a plate of buttery croissants with bite taken out of one piece, a cup of tea on the side, and a half-finished crossword with a folded over newspaper tucked under the cup conjures an entire vignette.

I shot this image for a blog post about Sunday lunch. The simple props, plates in the background, and the carving knife and fork all suggest that lunch is about to be served.

A work surface with a dusting of flour, a rolling pin and cookie cutters immediately imply baking even if the cookies are not in the image. Sometimes Instagrammers use a series of step-by-step images to tell the story. A lead image of the all-but-empty plate can entice viewers to scroll through the next shots to see what was so appetizing.

Not all food has to be plated. Creating movement engages the eye. A knife and a few breadcrumbs on a cutting board next to a loaf of sliced bread implies that someone just cut the loaf. Make these accents complementary to the focal point of the shot and not a distraction. Sometimes images end up messy and over styled. Less, as they say, is more.

4. Use props and backgrounds to add interest.Food styling includes everything you see in the image, not just what is on the plate. The goal to find the best props to showcase the dish you are styling. Here are a few rules of thumb:

Choose a background that complements the dish. A background creates textural layers and gives context to the food. One or two folded tea towels tucked around a pot of stew set on a wooden board makes sense, but five would be excessive. Keep your images logical.

A red and white checked tablecloth under a plate of sushi would look jarring, but works well with a plate of pasta, or as shown here, gazpacho.

Avoid patterns and colors that distract. A chicken tagine in a distinctive white bowl looks stunning, but placed in a yellow bowl, it would just fade away. Brown colored foods can be notoriously hard to style. But they can work well in a distinctive dish with a vibrant garnish on top. A butternut squash soup in a dull earthenware bowl would look bland, but you could transform it in a white bowl with finely-chopped herbs on top.

Choose complementary colors. Oranges set against a cobalt blue background work well. Monochromatic backgrounds, plates and linens are fine with a bright pop of color. A saffron-colored soup would look stunning in a dark bowl, placed on top of a black slate, with a curled-handled spoon on its side.

Use white or monochromatic plates and serving pieces. Plate food on smaller plates and bowls. Small portions look more appetizing.

Collect napkins and linens. I hunt down tea towels and linen napkins in different colors in antique shops and garage sales. A folded piece of cloth adds movement and life to an image. Vintage tablecloths can add textural background layers.

Top-down views are not always best. Focus on the most important aspect of the dish. In this case, the height of the souffle would be lost when viewed from above. I used a neutral colored linen so as not to distract from the star of the shot.

Get rid of marks. You would be amazed at how often fingerprints show up on silverware or stemware. Have plenty of clean kitchen towels on hand to wipe down the surfaces of everything you use in the shoot, so that smudges and prints don’t appear on camera. If they do, the plate or utensil just doesn’t look clean.

5. The food is always the star.

Here a few useful tips to tuck up your sleeve when prepping food for a photo shoot:

Show only the best quality ingredients. Small blemishes really show up in photographs. This is essential if you show produce.

Use individual ingredients as a prop. A bowl of lemons next to a lemon tart gives the impression that you just prepared the dish. Viewers can imagine the transformation from raw ingredient to finished dish. This is an easy way to improve your food styling.

Heat is the enemy of cooked food. Everything wilts under lights, so being prepared is key. A sizzling steak will start to dry out and look dull within 20 minutes. Fats begin to congeal. Undercooking food helps preserve its appeal. (Remember how you cooked the food if you are going to eat it, though! Because we eat everything on our shoots, I prep the sets with stand-ins for positioning, and then finish the dish at the last minute so that it is fresh out of the oven, or off the stove.)

Don’t dress salads until the very last second, and even then, hardly at all. Small brushes are useful here to “paint” on a little of the vinaigrette. Use too much and the acidity in the dressing will wilt the greens.

Tweezers are your friend. There will always be an errant piece of chive or the curl of a piece of arugula that is not quite right. It’s hard to pick those pieces out with your fingers and not disturb everything. Hence the tweezers.

Garnish dishes with complementary ingredients. Herbs, salt, pepper, powdered sugar, or nuts add another layer of texture to your image.

Make brown food look good! The repeated pattern of the gratin dishes, set on a dark background, and the warm side lighting, made the cheesy topping pop in the photo.

Food styling should be natural and uncomplicated. Resist the temptation to over-style a dish. You want food that looks good enough to eat, not so pretty that you wouldn’t want to touch it. The goal is to have viewers feel that they could pull up a chair to the table and dig in.

***

Pascale Beale grew up in England and France, where she learned classical French culinary techniques from her grandmother, and Provençal-Mediterranean cooking from her mother. She is an award-winning columnist for Edible Santa Barbara, and the author of nine cookbooks. Encouraged and inspired by her friendships with Julia Child, Michel Richard and Alain Giraud, in 1999 she founded Pascale’s Kitchen, a Santa Barbara, California-based cooking school devoted to California-Mediterranean cuisine. In addition to her classes, she has an IGTV and YouTube Cooking Channel. Find her recipes and online store at www.pascaleskitchen.com and weekly live classes on Instagram at @pascaleskitchen.

The post Tons of Tips to Improve Your Food Styling appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

March 2, 2021

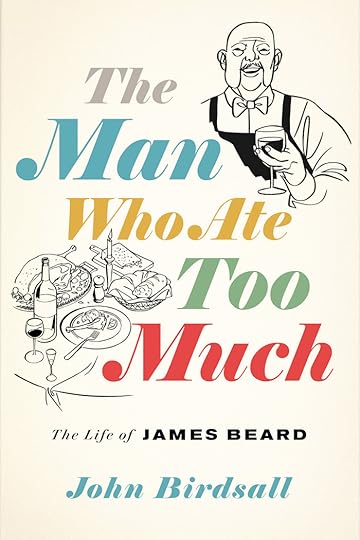

Q&A: John Birdsall on Writing a Profile of James Beard

Recently I had the pleasure of reading The Man Who Ate Too Much, by John Birdsall, a two-time James Beard Award-winning author and a writer I’ve admired since his early days as a critic. John combined scholarly research with the skills of a novelist to create this nuanced portrait of the famous cookbook author and personality. I wanted to find out about his process and methods of writing a profile about James Beard, especially since profiles are rare in the food world. Here is our interview:

Recently I had the pleasure of reading The Man Who Ate Too Much, by John Birdsall, a two-time James Beard Award-winning author and a writer I’ve admired since his early days as a critic. John combined scholarly research with the skills of a novelist to create this nuanced portrait of the famous cookbook author and personality. I wanted to find out about his process and methods of writing a profile about James Beard, especially since profiles are rare in the food world. Here is our interview:

A. When I was a chef, back in the late 1980s, I cooked at a restaurant in San Francisco with a focus on regional American cooking. I became familiar with Beard’s 1972 masterpiece, James Beard’s American Cookery. That book has a particular language—the recipes, the sketches, the way it’s designed. It intrigued me.

Later, in 2013, I wrote an essay for Lucky Peach magazine titled “America, Your Food Is So Gay,” about the influence on American cooking of three closeted cookbook authors of the mid- to late-20th century: Richard Olney, Craig Claiborne, and Beard. That piece had a big impact—I won a James Beard Award for it, and many readers, chefs and others, reached out.

Beard lingered in my imagination for a few years. He seemed the most interesting of the three, someone who was a household name for over three decades in the 20th century, yet who had to obfuscate. He rewrote his story, hid behind an image, and created myths about himself to conceal his homosexuality. I was fascinated to learn how that could possibly be.

Q. How long did it take to research and write this book?A. It took ten months to write the proposal for the book—most of 2016. I did some research for the proposal (I sort of arrogantly thought I’d done a lot), but, as it turned out, I’d only scratched the surface. My agents and I sold my book to W.W. Norton in early 2017 (the legendary editor Maria Guarnaschelli, who recently passed away, acquired it). Research and writing took pretty much every working minute of my life for the next three years.

While dozens of food memoirs exist, few food writers have attempted a book-length profile. Perhaps it’s because of the amount of research and complexity involved.

I wrote three major drafts—not just minor revisions from draft to draft but some pretty intricate reworking. I was so naive when I began, thinking I’d take a year purely devoted to research, and spend another year writing. It was nearly as clean as that: I was feverishly doing research until the last draft was nailed down (actually, it continued after that!). A biography is a beast of a thing to take on, and James Beard had a very full, very intricate life.

Q. Was it more fun to do the research than to write?A. I was so consumed with the research. It’s addictive. Each piece of it comes with multiple threads leading to other pieces, with multiple threads leading to yet more pieces. You definitely need a good editor to step in and let you know when you’re getting sidetracked, following something that might be interesting but that isn’t central to the book. It’s so easy to lose perspective.

And writing about a closeted subject has loads of other challenges. Beard erased lots of clues about his life. He and his friends destroyed letters deemed “incriminating;” that is, that revealed his sexuality or too much about his private life. So there was an added layer of detective work.

Actually, it felt like archeology: finding shards and traces of information and digging to find more. Sometimes it took intuition: having a feeling that I’d find something down some avenue. My most successful intuitive find was at the ONE archives at USC. They have papers relating to the early years of the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay rights organizations in the US. I had a hunch that Beard would have a connection to Mattachine activists. I made a special trip to LA and spent a day in the archives. In the last box of letters I found something: A letter from a friend of Beard’s, ordering a gift subscription of the organization’s magazine in 1957. Definitely a high point of the whole project.

But for every success, there were a bunch of dead ends. Writing, by contrast, felt much surer: an act of hunkering down in my office.

Q. What was the easiest part?A. There’s no easy part! That’s sort of a joke, but not really. I mean, writing a biography, something that has a long life, that will shape the public’s understanding of the subject for decades to come, is a huge responsibility. At times I felt paralyzed by it. In a weird way I felt Beard’s ghost as a very present companion through all if it. I felt that I was able to share in his emotions, at times in his life’s story, to feel his triumphs and deep sorrows.

At the same time, people who end up being my sources of information—people who knew Beard—often had their own ideas about the biography I should be writing. The thing is, though, they didn’t have all of the information. They knew Beard in a certain way at a particular time.

Being a biographer means you must keep to your convictions about your subject, writing the story of a life as you understand it, with all of the information before you. There’s a saying about writing a biography: “Shoot the widow,” meaning don’t let anyone tell you how to write about your subject, even sources who were very close to them. It’s important to stay clear of anyone’s agenda about your subject, and especially, as in Beard’s case, if there was a sort of conspiracy among those who knew him to keep his private life a secret.

Q. How did you learn to write nonfiction like a novel?A. It felt natural for Beard’s life, which had operatic plot twists, secrets and betrayals, and soaring success and dark corners. One of his goals as a cookbook author was to write in a narrative style. But except for his 1964 book Delights and Prejudices, he was never able to do it, partly because he wasn’t a particularly skilled writer, but mostly because cookbook publishers wanted comprehensive recipe collections, like Joy of Cooking, not singular narratives with recipes. Anyway, writing in a strong narrative style seemed appropriate to Beard’s life.

I wanted food to be a major driver of the story of his life: meals he’d had that changed the course of his life, dishes he cooked as expressions of love, or longing. Focusing on food made a novelistic approach appropriate.

And, I mean, Beard was a huge character who thought, in many ways, like an actor (which he’d trained to be). I wanted the tone of my bio to swing as far from academic as possible, which is why I included really copious endnotes. In a way, it’s two biographies: the main narrative and the documentation in the notes.

Q. What was the editing process like?A. My editor at Norton, Melanie Tortorolli, was such a pleasure to work with. She inherited my book after Maria Guarnaschelli retired, as I mentioned earlier. And as I got into the research, my manuscript had a slightly different emphasis than the one in my original proposal. But Melanie was amazing, acknowledging the shift but giving me her blessing to take the book where it needed to go.

Q. Beard borrowed recipes from other writers and published them as his own. Today’s food writers “adapt” recipes all the time. Why was this approach frowned upon?A. Yes, lots of cookbook authors plagiarized others, or (which is still common, if not universal) tweaked existing recipes, sometimes only slightly, “adapting” them to make them their own. Publishing standards were looser when James Beard wrote his first cookbooks in the early 1940s. It wasn’t until the mid-1950s that a major American publishing house, Doubleday, had a full-time editor dedicated to cookbooks, so many editors wouldn’t necessarily have known if an author committed plagiarism.

Published in 1959, this cookbook was the first American book to begin life as a paperback. According to Beard’s friend and editor, John Ferrone, it has been Beard’s bestseller.

Overall, there was a huge lack of transparency in cookbooks. Most Americans cooked recipes from huge comprehensive books, like the Betty Crocker Picture Cookbook or the Better Homes and Gardens Cookbook, even Joy of Cooking and Fannie Farmer, consistently among the best-selling cookbooks of the twentieth century. These were written by teams of editors and recipe testers who were “home economists” and rarely, if ever, named.

What made Beard’s plagiarizing disappointing was that he portrayed himself as an author. Indeed, the appeal of his books was that he was a man of singular tastes and experience, and that you were buying his personality, as much as anything, his authorial knowledge. But yeah, cookbooks have a terrible history of transparency. The great editor Judith Jones of Knopf made sure Irene Sax, Beard’s ghostwriter for his last book, Beard on Pasta, stayed a ghost. Jones didn’t even invite Sax to the book’s launch party. “And everybody in food in New York,” Sax told me, “was invited to that party.”

Q. What would you say to writers who might want to approach a complicated subject?A. Complexity is truth. We’re all deeply complex, flawed individuals who live surrounded by nuance and contradictions. Writing successful profiles, especially of people in food, especially at this moment when food media is facing a reckoning about the past, calls for complexity. Even for a subject you’re excited about, someone you believe has made incredible contributions, don’t shy away from including discordant notes. It’ll ground your writing, and make your subject even more convincing.

And all of us who write, whatever our subjects or our field, we have an obligation to keep a certain distance from our subjects, to cultivate the skills of a critic, and to take a rounded, deeply considered approach to what we’re writing about. James Beard had serious character flaws, but they make his positive achievements seem even more impressive, and serve as a reminder that humanity is complicated.

The post Q&A: John Birdsall on Writing a Profile of James Beard appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

February 16, 2021

5 Ways to Maximize Cookbook Sales

Some news: I recently became an affiliate of Jason’s online cookbook publishing course for bloggers, content creators, and chefs. If you decide to take his course (which I recommend — his content compliments mine), enter the code WWFF for 30 percent off! I will earn a small commission. Now, here’s his guest post about how to maximize cookbook sales.

A guest post by Jason Logsdon

Your cookbook just came out. Congratulations! But your work isn’t done yet, you still need to sell it! These keys to maximize cookbook sales have helped me move more than 60,000 copies of the 15 books I’ve written and published.

Many of the sales were for my self published books, where the challenge of marketing and promotion was all on my shoulders.

Here are my five keys to maximize cookbook sales: 1. Mention your book everywhere.To sell lots of copies of your book, you need public exposure. And whether that exposure is a blog, podcast, tv show, social media accounts, or speaking engagements, you must constantly mention your book.

Authors tend to fall in the trap of assuming that “everyone knows I have a book.” After all, you toiled away on it for a year or longer and it’s now a part of your identity. However, most people don’t realize you have a book, even after you tell them…and tell them…and tell them.

Once when I had a book out, I mentioned it in every blog post I wrote, every podcast interview I gave, at least once a week on social media, and in every newsletter I sent out. And I STILL had people who had been following me for years who didn’t know.

You don’t need to be in your fans’ faces. But you do need to continually drop a mention of your new cookbook in all of your communication. These mentions result in small sales that will continue leading to more success.

2. Find and Cultivate Your Super Fans

In today’s noisy world, word of mouth is still effective. But when it comes to promoting your book, not all readers are created equal.

Finding and cultivating those readers who develop a strong connection with you and your content is key. These super fans are the ones who read everything you write, comment on social media and email you. They are the ones who will promote your book for you and share it with everyone they know.

I cultivate my relationships with super fans by making sure I respond to everything they write about me. I also comment on and share the content they post online, as well as call them out by name on my podcast and in my articles. Finally, I always send them review copies of my books. Not only does that make them feel like part of the launch process and my team, but it also leads to many great reviews right away.

Find these fans, make them feel included, and they will be your best salespeople!

3. Look for a company to partner with.

Partner with a company that is big in your niche. An example is the sous vide book I was publishing through Sterling Epicure. Through a deal with Instant Brands, Sterling rebranded my book as The Instant Pot Ultimate Sous Vide Cookbook. It became the official sous vide cookbook for the Instant Pot brand.

This partnership created brand recognition for my book that lead directly to sales. Instant Pot also bought copies in bulk to bring to trade shows to give away.

I partnered with a website retailer to create a custom version of this book. It sold thousands.

I partnered with Modernist Pantry, a seller of kitchen ingredients and supplies, to sell my self-published cookbook, Modernist Cooking Made Easy: Getting Started. We created a custom version that only Modernist Pantry can sell. It carries the company’s branding. They sell it as part of their “Getting started” kit. Over the last five years, Modernist Pantry has sold several thousand copies of my book.

4. Create wholesaling deals.

The most lucrative deals I’ve found are with companies that distribute other products in my niche. These are equipment manufacturers, creators of ingredients, or general distributors. These types of companies look for books to round out their merchandise. If your book is an authority on a product they sell, then it’s a natural fit for them to promote it.

Self publishers can sell directly to companies at wholesale rates. If you are working with a publisher, you can put them in touch with each other.

I sell my book, The Whipping Siphon, through Creamright, the largest distributor of whipping siphons in North America. Sous Vide Supreme sold my book Sous Vide Grilling on its website. Cedarlane Culinary, a general distributor of modernist equipment, sold my book Modernist Cooking Made Easy: Party Foods.

5. Stick with what makes you comfortable.

This is not an exhaustive list or “the only way” to maximize cookbook sales. It’s just what worked for me. And part of the reason it worked is because I enjoy these specific techniques.

Some authors use speaking engagements to sell large quantities of books. Others email copies to magazines and writers, hoping for reviews. And some hit the streets, looking for small wholesale or consignment deals at local stores. But none of those sound appealing to me.

Find what works for you and what you like to do. Selling books is an ongoing process. Make sure the sales methods you pick are those you can keep up for the long haul.

* * *

Jason Logsdon is a best selling author, public speaker and passionate home cook who explores everything from sous vide and whipping siphons to blow torches, foams, spheres and infusions. He has published 15 cookbooks which have sold more than 60,000 copies. He runs AmazingFoodMadeEasy.com, one of the largest sous vide and modernist cooking websites. His website MakeThatBacon.com is dedicated to helping food bloggers succeed. Jason is the creator of the video course Self Publishing 101: How to Publish a Printed Book on Amazon Using KDP and runs a free weekly newsletter.

Photo by Mathieu Turle on unsplash.com.

Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links.

The post 5 Ways to Maximize Cookbook Sales appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

February 2, 2021

Is 1/2 tablespoon the New Recipe Measurement?

It doesn’t matter if they’re plastic, metal, round or rectangular. I need lots of measuring spoons when I cook and bake. And a few years ago, I bought my first set that included a 1/2 tablespoon measure.

It doesn’t matter if they’re plastic, metal, round or rectangular. I need lots of measuring spoons when I cook and bake. And a few years ago, I bought my first set that included a 1/2 tablespoon measure.

Huh, I thought. I haven’t seen this before. The spoons have been pretty standard until recently: 1 tablespoon, 1 teaspoon, 1/2 teaspoon, 1/4 teaspoon, and sometimes 1/8 teaspoon. Then I got a second set that included 1/2 tablespoon measure. Something’s going on!

Up until now, I’ve changed recipes that call for that measurement, because we had no physical measure. Most recipe writers call for 1 1/2 teaspoons, which comes to 1/2 tablespoon. So I wondered whether there’s a revolt underway, at least from spoon manufacturers.

Should we start using this new measurement in recipes?For an answer, I turned to copy editor Suzanne Fass, who has written for my blog in the past. She was of two minds. If a reader has a 1/2 tablespoon measure, it’s fine if the recipe calls for it. “But how prevalent is that measurement in sets?” asks Suzanne. “How long has it been available?”

“New cooks who have only just outfitted their kitchens might have one, but cooks who have been at it longer, with older equipment, may not. If that size is just gradually joining spoon sets and is not yet found everywhere, I’d guess that not very many readers will have it.

“”I fear that far too many folks don’t know that it equals 1 1/2 teaspoons,” she added. “You don’t want to force most readers to do math. And they’ll hate you for it, or get it wrong, or both.

“I guess my bottom line is: Don’t write 1/2 tablespoon.”

What about you? Do you have this newer measure? Have you been stating 1/2 tablespoon in your recipe ingredients list? Will you now? Let’s get it straightened out.

* * *

(Photo by Kara Eads on Unsplash)

The post Is 1/2 tablespoon the New Recipe Measurement? appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

January 19, 2021

Is a Work-for-Hire Cookbook Worth It?

In January, 2020, my husband asked me what were my top goals for the year. Instinctively, I said, “I want to write a cookbook.” At the time, I didn’t know that would mean a work-for-hire cookbook.

A few weeks later, I received a cookbook offer from Callisto Media. The editor wanted a cookbook on world curries made easy, using an electric pressure cooker. Here was a topic that fit my interests and aligned with the recipes on my blog.

I had heard about Callisto from two food blogger friends who published with them. I also read Priya Krishna’s article in the New York Times that highlighted the negatives about writing a work-for-hire cookbook. After brief consideration, I accepted the offer, purely to gain the experience of writing a cookbook.

A work-for-hire cookbook means that the publisher engages services for a fee. That meant doing the research, recipe and content development, writing, editing and rewriting, all for a fixed, full and final compensation. Unlike traditional book offers, I didn’t receive an advance or royalties. The publisher retained all rights to the book, including the proceeds from book sales.

A work-for-hire cookbook means that the publisher engages services for a fee. That meant doing the research, recipe and content development, writing, editing and rewriting, all for a fixed, full and final compensation. Unlike traditional book offers, I didn’t receive an advance or royalties. The publisher retained all rights to the book, including the proceeds from book sales.

Callisto paid me to deliver 75 recipes along with other content. I agreed to produce close to 30,000 words in seven weeks.

The Electric Pressure Cooker Curry Cookbook: 75 Recipes From India, Thailand, the Caribbean, and Beyond, was published in August, 2020, just eight months later. Since then, I get many queries from fellow and aspiring food bloggers who want to know more about the book offer and if the cookbook was really worth it. So I’ll share my experience, along with the advantages and some trade-offs.

Let me answer a few questions about the work-for-hire process:1. The schedule sounds crazy. How did you do it?I had to submit the final manuscript with 75 recipes, plus other content, in less than seven weeks. That meant researching, developing, testing, writing and finalizing two recipes a day, plus time to research and write other content.

Having been a graphic designer prior to food blogging, I knew about tight timelines. I also knew that this highly ambitious deadline needed a fail-proof plan. The publisher provided a helpful outline and a timeline with multiple milestones. They were great templates to divide the content and recipes for my schedule.

Just like any cookbook author, I wanted every recipe to be fail-proof and enjoyable. I wanted curry lovers to expand their palette beyond the common Indian and Asian curries. And finally, I wanted to tell a story about how curry originated, travelled the world and transformed into hundreds of delicious dishes. And all that needed time!

Just like any cookbook author, I wanted every recipe to be fail-proof and enjoyable. I wanted curry lovers to expand their palette beyond the common Indian and Asian curries. And finally, I wanted to tell a story about how curry originated, travelled the world and transformed into hundreds of delicious dishes. And all that needed time!

Fortunately, my husband and teenage daughters stepped in. While I juggled all aspects of the book, they ran multiple grocery trips, took over my mommy duties and took on other responsibilities. As my sous-chefs, they cleaned up after I developed and tested recipes, helped me prep for the following day, and provided feedback on the dishes.

With such a tight timeline, I started my day at 6 a.m. and worked past midnight. If a recipe didn’t work, I remade it right away, sometimes twice, until I was satisfied. Towards the end, when I was running out of time, I reached out to my blogger friends and a few of Spice Cravings’ frequent readers on Instagram and Facebook to ask if they would test a recipe for me. Luckily, most obliged.

I continued to test recipes during the three stages of editing. My editor was kind enough to accommodate those changes. That’s how I tested every recipe multiple times before it made it to print. I am proud to say that I met all my deadlines. Discipline and hard work got me through, plus help from family and friends.

2. Was the work-for-hire cookbook experience worth it, personally and financially?Yes. In retrospect, it depends on what you want from the experience. The financial part isn’t so black or white. It depends on what you’re earning from your blog including ad revenue, sponsorships or other paid recipe development projects at the time. Here are the pros and cons:

What was hard, but expected: Limited time. There was less time for my blog, which affected content creation, income, and building my brand image on social media.No time. There was no time for other income opportunities, such as sponsorships and other recipe development.So tired. I worked crazy hours with no time for family and friends, or self-care. Those seven weeks were physically and mentally exhausting.What was worth it: Terrific exposure. I was less than three years into blogging. Getting a cookbook offer isn’t easy when you’re that early in your career. Even though my blog was fairly established at the time, it’s great exposure and an endorsement for up-and-coming bloggers.A great learning experience. The streamlined, well researched outline and disciplined editorial process at Callisto taught me how to weave the book together through my recipes. It introduced me to all the elements that go into writing a good cookbook.

Overall, writing this cookbook was a great learning experience. But having done one cookbook this way, why do it again? I have been approached with similar opportunities and I turned them down. Here are a few reasons why:

It’s not enough money. I want to be paid at par with industry standards.There weren’t enough photos. My cookbook has twenty full page pictures, with only nine pictured recipes including the cover. It’s a real challenge to sell a cookbook with limited photos. That’s the only negative feedback I got on Amazon reviews.I want royalties from book sales next time. Call me a material girl, but I want to be rewarded for all the time, effort and creativity I put into ongoing promotions of my cookbook.Writing a work-for-hire cookbook not necessarily a stepping stone to a dream book deal. Cookbooks are a crowded space. Those with a high social media presence are most in demand as authors. Also, any esteemed publisher would want to see how well a first book sold. Due to the limited photos, that is not going to be a ground-breaking number for me.I am proud of the Electric Pressure Cooker Curry Cookbook. The reviews tell me that people enjoy the recipes, and in the end that’s what matters. After all, that’s why I started Spice Cravings in 2017.

* * *

Aneesha Gupta is a recipe developer, photographer, writer, and food blogger who has been featured on NBC News, Yahoo, MSN, and more. She is the founder of Spice Cravings, where she shares quick and easy international recipes that are low in effort and big on taste. With step-by-step instructions and smart shortcuts, her recipes are doable for busy families, even on weeknights.

The post Is a Work-for-Hire Cookbook Worth It? appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

January 5, 2021

10 Mistakes Not to Make When Working with an Editor

By Amy Sherman

By Amy Sherman

Writers have mixed feelings about working with an editor. As a freelance writer, I get it. When I started writing about food in 2003, I didn’t have an editor because I was writing for my own site. Even when I blogged for outlets such as Epicurious, KQED and Frommer’s, my editors were hands off. As my career progressed and I wrote articles for consumer, trade and academic publications, my editors became more involved. I learned that an editor could make my writing much better.

But sometimes working with an editor was just plain frustrating. I struggled with vague assignments and a lack of clear feedback. Other times I read a final story and barely recognized it, because the editor had taken it in a different direction. Too frequently my editors disappeared, not responding to my emails or calls.

Last year I became editor-in-chief for a new site, the Cheese Professor. A few months later I was also hired as editor-in-chief of the Alcohol Professor. My goal was to be the editor I wished I had as a freelance writer. One of the first things I did was create writer guidelines for both sites. Submission or writer’s guidelines are less common than they used to be, which is a shame. I vowed to communicate clearly, to be flexible, patient and understanding. I would always respond to their emails.

But sometimes, when I work with writers, things don’t go as smoothly as I would like. I hope by sharing my pet peeves that you’ll see some ways to improve your relationships with your editors.

Here are 10 mistakes writers make when working with an editor:

1. Boring or vague pitches.

A pitch should sell me on your idea. Tell me enough to entice me to assign the proposed story. Convince me you are the right person to write it. “I want to write about X” is not a compelling pitch.

2. Disregarding the guidelines.

I can’t force anyone to read them. Before every pitch or assignment, look at the publication’s guidelines. I keep them in Google Docs so they are always up to date.

3. Not writing for the audience.

The first rule of writing should be to know your audience. The audience for our publications is a combination of industry professionals and enthusiasts. Yet I find many writers write for the consumer. Also, our publication isn’t regional, but writers submit stories that are too locally focused.

4. Disappearing.

As a freelance writer, I hate it when editors disappear and ghost me. But writers do the same thing. Please answer emails from an editor promptly. If you need an extension on a deadline, ask for one as soon as possible.

5. Writing the wrong story.

I try to be clear in my assignments, but if writers don’t read them thoroughly or understand them, it’s likely going to mean revisions. That means more work for both of us.

6. Grammatical and spelling mistakes.

It should go without saying, but writers must copyedit and proofread their stories before sending them to editors. Most word processing applications and platforms have built in tools, so use them. There is no excuse for not using the free version of Grammarly.

Review your story the day after you write it. You’ll see it with fresh eyes, where it’s easier to catch mistakes. (And of course you have planned for this, so you can make your deadline.)

A photo for a story for the Cheese Professor, by freelancer Sarah Fritsche, about the fondue served at The Matterhorn, a San Francisco restaurant. The story features tips, a recipe, and photos by the author. (Photo by Angela Pham on Unsplash.)

7. Phoning it in.

Some PR people provide a ton of material about their product, company or service. Some writers just tweak the information and turn it in to me. Other writers conduct an email interview and then barely edit it and submit it. Just as a teacher knows when a student has plagiarized, a keen editor can see when a writer hasn’t done the necessary work to write a good story.

8. Not formatting photos correctly.

I wish I had a photo editor, but I don’t. I don’t want to have to download a ton of photos, resize them or hunt down photo credits. Even worse? Writers who don’t submit images at all or submit blurry ones I can’t use. The photo specs are in the guidelines.

9. Invoicing incorrectly.

Invoicing can be a pain, especially if you write for lots of outlets or clients. Everyone has a different procedure. But if you want to get paid, you’ll need to follow the invoicing instructions. And you guessed it, the invoicing instructions are in the guidelines!

10. Not sharing your published story on social media.

It’s not required, but if writers don’t share their stories on social media, it makes me wonder if they are proud of the finished story or embarrassed by it? The truth is, the more traffic their stories get, the more likely I am to work with them again.

In a nutshell, editors don’t just value good writing. They value detail oriented, conscientious writers who follow instructions and meet deadlines. To build a strong relationship with an editor, start by reading their publication or website. Ask the editor for the guidelines before sending in a pitch. If you want to pitch me, check out the Cheese Professor writer’s guidelines or the Alcohol Professor writer’s guidelines. They include all the information you need to know about the sites, the kinds of stories we assign and more.

* * *

Amy Sherman began her food blog, Cooking with Amy, in 2003. She has been a freelance writer and recipe developer and is the author of two cookbooks. Currently Amy is the editor-in-chief of the Cheese Professor and the Alcohol Professor websites.

The post 10 Mistakes Not to Make When Working with an Editor appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

December 22, 2020

24 Fascinating Food Writing Links for Writers and Bloggers

I hope it’s been a good year for you. It might have been a little harder than usual to concentrate. That’s why a list of great food writing links could be just what you need right now. As we approach the holidays, take a break from Christmas cookie decorating to get caught up on our industry.

I hope it’s been a good year for you. It might have been a little harder than usual to concentrate. That’s why a list of great food writing links could be just what you need right now. As we approach the holidays, take a break from Christmas cookie decorating to get caught up on our industry.

And some of these links are just plain fun anyway.

If you’d like to find more terrific stories like these, they’re in my free twice-monthly newsletter on food writing. So don’t worry about tracking down these stories all by yourself. Twice a month, they’ll show up in your email.

Here’s my latest list of can’t-miss food writing links:

1. Deb Perelman is Thankful for Tacos. A New Yorker interview wonders why the Smitten Kitchen blogger is not as famous as Martha and Ina.

2. Writer Mayukh Sen is Crafting a New Food Media Playbook. The award-winning writer discusses his process.

3. NPR’s best cookbooks of the year. A mix of familiar comfort food and the more adventurous.

4. The best cookbooks of 2020. The San Francisco Chronicle critics felt much better about what’s on offer this year compared to last.

5. The Joylessness of Cooking. Helen Rosner holds forth about a “crisis of culinary anhedonia.”

6. How a Fortuitous Email Led to Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen. Another in the series of Cherry Bombe features about how people get their cookbook deals and write their books.

7. Building a longer table: Jamila Robinson’s vision for a more socially and racially equitable restaurant world. Journalist Jamila Robinson delves into this topic and how food writing needs to change.

8. What Did Bon Appétit Do Now? Well, they stepped in it, yet again.

9. A Case for a More Regional Understanding of Food. The Western food media needs to deconstruct its monoliths, says author Bettina Makalintal.

10. Is American Dietetics a White-Bread World? These Dietitians Think So. Dieticians need to pay more attention to different diets, body types and lives. (New York Times possible paywall.)

11. Nigella Lawson stuns Cook, Eat, Repeat viewers with ‘butter facial’ remark while making mash. Much ado about nothing, but you know how social media is.

12. Which Food Publication Won the 2020 Holiday Cookie Bake-off? Eater editors dish about which package they like best.

13. Best cookbooks and food writing of 2020. The UK Guardian stakes out its winners.

14. Just How White Is the Book Industry? The New York Times analyzes publishing and bestsellers. (New York Times possible paywall.)

15. Do you know about Exploding Topics? The site’s food page tells you what’s hot right now. Vegan keto? That’s a thing.

16. How Does Ina Do It? The New York Times profiles her rise. (Possible paywall.)

17. Time to get your publisher to submit your new book to the IACP awards.

18. A food blogger turned the tables on haters by creating ‘Shirley,’ a fake customer service representative who responds to mean comments. Amanda Rettke of the I Am Baker food blog has a ball with her new character.

19. The Substackerati. Substack is a venture-backed company featuring white male writers. So is this anything new?

20. A New York City Cookbook Store Survives. An interview with Matt Sartell of Kitchen Arts & Letters, which recently set up a successful GoFundMe campaign. Read on to see what kinds of cookbooks he’d like to see more of.

21. The Ultimate Texas Tacopedia. I don’t usually post food stories, but this piece is encyclopedic! I did not know about West Indian tacos, for example.

22. Yes, Chef: Here Are the Year’s Best Cookbooks. A food critic lists his favorites for Wired magazine.

23. The Challenge and Pleasures of Elizabeth David. Just discovered this, and what a great read it is.

24. The 19 Best Cookbooks to Give the Chic Chef This Holiday Season. So says Vogue magazine, with little explanation.

I’ll be back in 2021 for my 12th year of writing blog posts. Thanks so much for your support during this challenging time. It means the world to me!

Happy holidays! Here’s to a productive 2021.

The post 24 Fascinating Food Writing Links for Writers and Bloggers appeared first on Dianne Jacob, Will Write For Food.

By

By