Everett Maroon's Blog, page 22

August 9, 2012

A Better Dad Letter

I have loved you since the moment I saw you pass before my eyes, right before the doctor placed you on your mother’s chest. In truth, I loved you before then, and since we’re on the subject, I would say I was in deep, deep like with the very possibility of you, but certainly having the actual you around is much better.

I read a horrible letter the other day from a father who was cutting ties with his son only because his child had asserted he was gay. I’ve known people like this, who wielded their ignorance against their own families, and yes, it is astonishing how human beings can revolt against their own kin. But it does remind me that this is why we have chosen families, dear confidants, and supportive systems of loved ones that may or may not share DNA with us.

That man is misguided. It’s clear to me after only 11 months of knowing you, that my mission as your parent is to help you grow into the best person you can be, and I ought not attempt to control who you become–it’s folly, for one thing, and mean to boot. Yes, I should expose you to ideas, talk with you as you sort through your place in the world and what to make of this great big mess, and tell you I love you, but your path is your own. If you tell me tomorrow that you want to be known as Priscilla Queen of Splendiferousness, I’ll simply be astonished that you’re talking this soon. I won’t worry that it’s because we dressed you up like Liberace for Halloween last year–you did look fabulous, by the way.

I’m also not going to fret if you insist on playing with trucks and dinosaurs, because my goal is to avoid foreclosing possibilities for you in your childhood. And when you tell me you hate me and to leave you alone at 13, I’ll remind myself that this is normal for adolescence. You need to find your independence.

So calling me at 19 to tell me you’re gay, joining a circus, found the love of your life, or declaring your membership in the NRA, will all be met with support (though do expect some literature about gun violence if you go the NRA route, my love). I will never write a letter instructing you not to send me any presents or to imply you need not show up at my funeral. I hope that no such stupidity and cruelty ever comes between us, Emile. You are my love and I owe it to you to model through the rest of my life, the kind of person I hope you aspire to as an adult. Generous, thoughtful, supportive, and genuine.

I hope you find love. It tends to come not when you are looking for it, at least in my experience. I really don’t care what the gender identity of your partner is, as long as they’re nice to you. Mutually supportive relationships are nice, too. I’m certainly not going to cut you off just because you fall for someone of the same sex! And I’ll try not to hold too high a bar for anyone you bring home to meet us, and I say that knowing it’s going to be challenging to live up to that. I’ll do my best.

Incidentally, that’s all I expect of you. To do your best. We’re going to make a lot of mistakes along the way, but that is how we folks improve over time.

Now then, there are a few guidelines I can impart that should increase your chances for success:

1. Never drink orange juice right after you’ve brushed your teeth.

2. No matter how appealing it may seem, never lick a steak knife.

3. Good friends agree to play by your rules some of the time. Great friends agree to make up the rules with you.

4. Cuts and bruises are totally worth the price for a fun afternoon. Lasting damage is not.

5. Yes, you should question authority. You should also question peer pressure, and anyone who doesn’t seem to respect you.

6. If you can’t talk to mom or me about it, find an adult you trust and talk to them.

7. Inside is for walking, and outside is for running and climbing trees, and watching the clouds, and plucking daisy petals, and counting the cars that drive past.

8. I’ll try not to lay down an inordinate number of rules to obey and in return, I hope you’ll try to listen when I remind you of the ones we do have.

9. Don’t hit or bite other people, even if they’re mean or you think they deserve it.

10. Don’t trust people who say they don’t like great stuff like chocolate or pizza.

I love you. We’re just about ready to celebrate your first birthday! I can’t wait to have even more wonderful days with you in your second year.

Dad

August 5, 2012

Ebb and Flow

A couple of weeks ago the Boy Scouts caused a stir when they concluded after a two-year assessment, to continue their ban on gay boys and men as scouts and scout leaders. Well, their ban on out gay boys and men, but whatever. On the heels of this the Internet exploded over news-certainly not sudden–that Chick-Fil-A gave substantial money to anti-gay interests, including groups who advocate for killing gay and lesbian people in Uganda, since advocating for that kind of thing on US soil is a big no-no. And while this was going on, NASA was preparing to launch its most ambitious rover mission to Mars. Certainly NASA doesn’t ban people of a queer inclination, but that’s beside the point. My point, since I’ve buried it at the end of this paragraph, is that we humans are capable of astounding progress and horrifying cruelty, and this never fails to fascinate me.

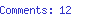

I can’t believe we are still arguing about whether global warming is real or not. Seriously, look at this glacier.

Or this one.

The first photos are from Alaska and the second glacier is the one that feeds the Columbia River from Alberta through the Pacific Northwest and out to the Pacific through Oregon. Last month a section of Greenland fell into the ocean, a section about twice the size of Manhattan. But like that old saying, if a tree falls in a forest and no one hears it, we take these enormous moments as abstractions. Unless we’re regular donors to Greenpeace, but you get the idea. With evidence that sea levels are rising, average temperatures are hotter, and new weather patterns are emerging in response to these other climate changes,* we still give public consideration that this is simply part of the natural course of Earth and/or an act of God who is pissed that the Boy Scouts even thought about letting gays into its organization.

The first photos are from Alaska and the second glacier is the one that feeds the Columbia River from Alberta through the Pacific Northwest and out to the Pacific through Oregon. Last month a section of Greenland fell into the ocean, a section about twice the size of Manhattan. But like that old saying, if a tree falls in a forest and no one hears it, we take these enormous moments as abstractions. Unless we’re regular donors to Greenpeace, but you get the idea. With evidence that sea levels are rising, average temperatures are hotter, and new weather patterns are emerging in response to these other climate changes,* we still give public consideration that this is simply part of the natural course of Earth and/or an act of God who is pissed that the Boy Scouts even thought about letting gays into its organization.

Why do we entertain notions that one can only describe as foolish at best? Or more accurately, why do masses of humans who know better allow the most superstitious few of us to direct these conversations? Why don’t we pull the same tree-in-a-forest logic on them and let them spout off their ridiculousness (Haiti’s earthquake was caused by a deal with the devil, Japan’s tsunami is because their emperor sleeps with Succubi) in a media vacuum?

It must be that something draws us to keeping offensive, idiotic notions like these in the room. When the Tea Party formed in the aftermath of Barack Obama’s election in 2009, there was a lot of press attention to the sizes of their crowds at rallys, so much so that some news outlets *cough cough FoxNews cough* doctored the footage** to suggest there were more people protesting the communist socialist President who was “just like” Hitler. Fast forward to the brouhaha around Chick-Fil-A, and the images of people standing in line to show support for being proudly bigoted against LGBT people, and once again the news media frames these conversations about civil rights and freedom of thought as a pissing contest of which group has more people in it. I can’t think of a more vapid way to think about religion, liberty, the civil rights of a community, and fried chicken.

The reality is that the number of Americans now in favor of same-sex marriage has reached parity with those who are not, but more importantly, the vast majority of voters are in favor of anti-discrimination laws for LGBT people, and there is strong support for similar laws targeting most every marginalized community except undocumented workers. (Which is something we need to work on, yes.)

One need only look at NBC’s Olympics coverage to find an example of how the press creates a non-reality for us to watch on television. I much prefer the stakes of misrepresenting sporting events than making people believe in the lie of a large, vocal extreme-right populace. Then I find myself in very muddy territory–am I arguing that these misrepresentations cause violence to people? Don’t I trust Americans to know reality from non-reality? To do the right thing?

When the right thing is buying a greasy fried chicken sandwich, I’m not sure I trust everyone, no. At some point within this stream of disconsciousness, some individuals will begin to believe the narrative and not their material reality. It’s at play when people who are not served by the Republican tax policy vote against their own interests and support GOP candidates at the polls. It’s evidenced when closeted gay men in Congress advocate against LGBT issues. It’s certainly in action when Christians put aside the traditional calls to do work for the poor and begin blaming poor people for everything from the housing market crash to the federal budget deficit.

Please don’t think I see some kind of straight [sic] line between news stories and rampant erroneous beliefs in America; I’m quite sure it’s more nuanced and convoluted than this. But somewhere in the midst of increased pressure on news outlets for ratings, competition from a bazillion Internet sites and blogs, a more masterful grip on online tools by ideologues of both poles, our longstanding historical amnesia for political and social moments of the past, and the harsh financial pressure from a near-flat economy, many people have begun to earnestly believe the narratives as presented to them by the media machine, which itself is a near-monopoly at this point.

All I can think is that at some point, we will shift direction again. We must. There is only so long humans can afford to interpret the melting of the earth as an outlier moment, only so long we can give airtime to bigots of any persuasion before those communities will resist in an organized fashion, and only so long we can delude ourselves in believing the singular greatness of our nation until it is clear that the rest of the globe has passed by us. Perhaps we need these false narratives right now because our reality feels so grim, but instead I’d rather we wake from our created dream early and have the hard conversations now while there is still time to correct some of these ongoing mistakes.

Ebb and flow.

*By the way, that linkage is brought to you by a scientist from NASA. There go those gay-loving scientists again.

**CBS News also broadcast images from a non-Tea Party rally that showed a much larger group of people in protest.

July 31, 2012

Usable Metaphors to Get over Rejection

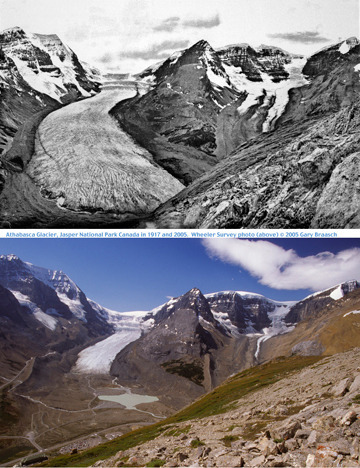

Every now and again I write a little ditty about rejection letters, because in the world of the writer, they happen with great frequency. As many, many more talented authors than I have waxed about how rejections are good events because they push the writer forward, and are a sign that one is engaging in the publication enterprise.

Every now and again I write a little ditty about rejection letters, because in the world of the writer, they happen with great frequency. As many, many more talented authors than I have waxed about how rejections are good events because they push the writer forward, and are a sign that one is engaging in the publication enterprise.

But rejections sting. They can make us doubt our talent or our message or execution. I’ve heard more than once the dreaded “doesn’t rise above anecdote” when submitting short work. Don’t you dare write only an anecdote, even if our maximum word count is 1,000. Rejection can be frustrating enough that say, a garden variety writer like myself could lose the better part of the afternoon just stewing about the twelve words in the email from the journal editor.

Obsessing over the NOs doesn’t do us any good. With our future productivity and success in mind, let me jot down some metaphors to make rejection more palatable.

It’s like a beacon from an enigmatic civilization, in a galaxy far, far away—Writing, especially if you’re not workshopping a work-in-progress, is a lonely process. We can get lost in the murk of our own minds. As Einstein hypothesized, if a person is in total blackness and weightlessness, she cannot know if she is moving. Rejection letters give us some new information about our work. Even if all we read is a form rejection with no editorial reaction, it is a thin ping from another part of the universe that can help us assess what we need to improve in the piece, especially if it’s not the story’s first rejection.

It’s tough love from a guardian who wants us to be our best—Maybe we’ve gotten sloppy and submitted a piece that’s not quite ready, but we didn’t want to wait for the next open submission period, and the deadline was upon us. Maybe we knew this story was better suited for another literary journal or agent, but we sent it in anyway. Whatever the case, the resulting rejection letter is evidence that we need to get more discipline. That’s a positive thing, even if it hurts.

It’s like having a sex change, only not as complicated or annoying—Seriously, once you decide to live as the other gender, a lot of life’s grievances pale in comparison. I mean, not cancer probably, or surviving an airplane crash, but for the most part, sex change is a bigger mess to deal with. So when that next rejection rolls in—and it will—just tell yourself, “hey, it’s easier to get over than transition!” That’ll put a smile on your face.

It’s like a certificate of authenticity—I know, the standard idea with rejections is that they’re evidence we’re not good writers. “Don’t quit your day job,” blah blah blah. But let’s reframe rejection a little. As I mentioned earlier, we can only receive a rejection note because at some previous point, we engaged with the publishing industry. Plumbers don’t engage publishers. Doctors don’t measure their worth in how many submissions they’ve sent out to editors. Writers do. Getting rejected means we wrote something worth sending in for consideration, and that is evidence that we’re writing. And what do writers do? They write.

And most definitely, they get rejected.

Keep writing.

July 24, 2012

Spree Killer Contradictions

I refuse to write his name because he’s not the point, the is-he-or-isn’t-he faking psychosis mass murderer who destroyed dozens of families last weekend in his quest for selfishness. As much as we want to aim our fingers at him in judgment, this act of violence isn’t about him, just as it wouldn’t be about the lone terrorist who stuffed a bomb into his underwear, or the two disgruntled men who took out the Federal building in Oklahoma City all those Aprils ago. I don’t absolve any of these men of their acts, certainly not, but I can’t abide providing them the public attention they crave and that they receive from so many media outlets.

One wonders where people even get the idea (CSI) to gun down (Call of Duty) large groups of people (The Closer, NCIS) in a twisted sense of justice (Breaking Bad, Dexter) or superhuman power (The X-Men, The Dark Knight). And we could ponder why we see these events as solely the actions of a broken brain (Criminal Minds, Numb3rs, The Silence of the Lambs) are at their core individual episodes and not related in any way to larger systems that have a perverse need to produce violence.

I just don’t know how we get here, where a stream of life-ending bullets descends onto a crowd gathered for a movie, and it takes everyone too long to realize they’re actually under attack. Susanne called this aspect of Friday night’s tragedy particularly sad, and she’s got a good point there. Who are we as a culture that extreme violence is so much of our contemporary entertainment narratives?

Also weird to me is the utter silence around potentially productive conversations we could be having right now but aren’t. The National Rifle Association balked when people were upset about a tweet they posted after the shooting:

Well, they didn’t know about the deaths, sheesh. But soon enough there were calls not to even discuss gun control in light of the legal purchases this latest murderer made in advance of wounding more than 70 people and killing 12. It wasn’t just presumed GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney who said that “now is not the time” to talk about gun control legislation; Dianne Feinstein cautioned against the Obama Administration attempting to win points on the issue, and Senator Feinstein is a long-time gun control advocate.

After the Twin Towers collapsed on September 11, 2001, did anyone say that then was not the time to talk about homeland security? In fact, I’m pretty sure we went in the other direction, banning regular-sized shampoo bottles on carryon luggage, and subjecting Americans to xray machines for even the shortest of puddle jumping flights. Our conservative Republican President expanded the Federal Government in response, and nobody from the NRA or any right-wing organization asked for a waiting period before we jumped to conclusions about who had attacked us and why. In fact, the NRA isn’t exactly familiar with the concept “waiting period.”

So I am suspicious about calling off discussions about assault rifles now. Why is it okay in one instance to respond in the heat of our shock, and not in another? Why is it acceptable to draw stereotypical conclusions when the perpetrator of gross violence is of color but not okay to question what drives some white men to kill 6-year-old children? When are we allowed to interrogate the thick stream of contradiction that floods our collective consciousness after horrific events?

I’ll do my part, as a bleeding heart liberal, to understand the perspective of the other side. I think firing a shotgun at a clay pigeon is terrific fun. It feels exciting to hold a heavy weapon in my arms, propped against my shoulder, hearing the target shatter and crash to the ground, despite the bright orange plugs nuzzled in my ear canals. The click as I pull back and discharge the plastic shell, reloading for the next pull of the launcher. I bet I’d also like firing a handgun at a paper target, because, hello, Mark Harmon makes it look so enticing when he does it. I have radical left friends who insist that they are armed because the progressives need their own weapons for when the revolution rolls around, and I can’t argue with them on that. This shotgun or handgun that I’m talking about, however, is a far cry from an assault rifle with a 100-clip magazine. I am not going to say that all guns are evil, but I don’t buy the line about “people killing people,” either. Hunters who act responsibly are not in the same class as mass murderers, and mass murderers are too well supported by lax gun laws. Of course someone with the means and the intent will find a way to kill scores of people, but does it have to be legal to ready oneself for such an atrocity?

Also, why shouldn’t purchasing four firearms in 60 days set off a red flag to authorities? If I buy too much fertilizer or Sudafed I may be subject to investigation–why are assault rifles any different?

Because fertilizer makers aren’t part of a money-rich lobby, and firearms are. It’s that simple. The NRA, originally a gun club for men after the Civil War to improve their clumsy shooting skills, has evolved into a cornerstone of the extreme right, and if I were a gun owner, I might be more than a little concerned about that. Like I feel about the arch-conservative bishops who are currently ruining American Catholicism, I would shake my head in sadness that my philosophy around responsible gun ownership was overshadowed by people with delusions of grandeur or anger. I might even call for a new way to regulate gun sales and manufacture in the United States, where 25 people a day (on average) die from gunshot wounds.

I don’t think it’s unreasonable to want a different dialogue this time around who we are as a country and what we value. It’s contradictory, in my opinion, to claim to be pro-life when we’re talking about humans who haven’t been born yet, but be pro assault rifle, when there is very little one can do with such a machine other than taking human life or pretending, in the woods with one’s friends, to take human life. It’s contradictory to tsk tsk the bravado that accompanied the Aurora shooter but write an article about how amazing the men who shielded their girlfriends from the bullets were (yes, they were amazing, but can we not see these as mirror moments of masculinity?). It’s contradictory to bloviate about terrorism when shooters are from the Middle East, but not call it terrorism when the person pulling the trigger is from Colorado. It’s contradictory to claim shock at real world violence yet never question the violence we consume as part of popular culture. And it’s most certainly contradictory to disallow debate about what underpinned this moment last weekend but continue so many already discredited conversations about our country in its place (I’m looking at you, Sheriff Arpaio, Donald Trump, and Mike Hukabee).

At some point, the pendulum of sanity has got to swing back to center, because where we are right now, in this world where a sexual assault survivor is charged with crime for naming her attackers on Twitter, where George Zimmerman gets to spout whatever ridiculousness he wants on national television, and where a trans woman who defended herself from beating and lacerations is sitting in a jail cell for two years–this world is not sustainable.

So let’s start with a discussion about entitlement, masculinity, and the availability of killing machines.

July 22, 2012

After the Agent Pitch

Emerging writers flock to conferences like the one just held by the Pacific Northwest Writers Association because they’re looking for information–from presenters with tips on craft and marketing, from fellow writers on lessons learned, from the bulletin board that lists local critique groups, and of course from editors and agents who are broadly viewed to hold the keys to the palace of publishing. We practice our pitches, memorize our log lines and synopses, update with lightning speed our writing credentials for our bios, all in the hopes that some paragon of the industry–or new agent looking to sign unknown authors–will ask for a partial manuscript. We feel the onslaught of butterflies invade our intestines when we’re instructed to give a specific subject line in our email message, like we’ve just learned the 21st Century’s version of “Open, Sesame.”

Emerging writers flock to conferences like the one just held by the Pacific Northwest Writers Association because they’re looking for information–from presenters with tips on craft and marketing, from fellow writers on lessons learned, from the bulletin board that lists local critique groups, and of course from editors and agents who are broadly viewed to hold the keys to the palace of publishing. We practice our pitches, memorize our log lines and synopses, update with lightning speed our writing credentials for our bios, all in the hopes that some paragon of the industry–or new agent looking to sign unknown authors–will ask for a partial manuscript. We feel the onslaught of butterflies invade our intestines when we’re instructed to give a specific subject line in our email message, like we’ve just learned the 21st Century’s version of “Open, Sesame.”

Before you click on that send button, do a few things:

1. Double-check the spelling of the agent or editor’s name–I know, it sounds so very basic, but do it anyway. They may still love your book idea, or they may stop reading and go to the next email message. Because there is always another email message waiting in the queue.

2. Only send what has been requested–If it’s 20 pages, don’t send 50. If they asked for the first three chapters, don’t send two or four. If they asked for your latest bio paragraph, don’t neglect sending that in the letter. Sure, this means tailoring each missive to each requesting agent, but this could be the first day of the rest of your career. These folks know what they’re capable of reading and they have their preferences, so check what you’re about to send with what they require.

3. Don’t ramble–Maybe you felt magic in those three minutes of the power pitch session, or perhaps the structure of the event reminded you of that time you made delicious eye contact during the speed dating night you signed up for a year ago, but refrain, under all circumstances, from attempting to relive it in your email note. First of all, they don’t care (and really, do we want them to?). Second, you are a blur in what was probably 8 hours of listening to people make their best cases for their projects, so that special sensation is yours alone. But most importantly, going on about how great it was to meet them at the conference is just a distraction from your project. And your project is the real focus here. Win them over with the words in your partial manuscript. As a bonus, you won’t kill your chances by coming off like a sociopath.

4. Make sure you reference whatever they’ve asked you to reference in the subject line–Often agents and editors use filters to deal with what are overwhelming amounts of email and paper letters. If they tell you to put their name in the subject line–one of the folks I met this weekend noted that–do it, because it may be the first line of defense against ending up in the slush pile. You worked hard to get the professional’s attention, so don’t waste that by forgetting any special instructions regarding the subject of the email. Unless you really really enjoy always standing on Square One.

5. Avoid mentioning any other project in the email than the one you spoke about earlier–If Ms. Agent told you she was curious about your swashbuckling pirate YA, don’t jam in references to the adult paranormal thriller you’ve also completed. She requested the one project, so only note the one project. Agents represent what they do for a reason, and they’re their reasons, not yours. If he or she takes you on as a client, then you can converse about all of the other glorious books in your cupboard or brain. Or cupboard brain, if that’s how your brain works–there’s no judging here.

6. Thank the professional again–Yes, you plunked down good money for the opportunities the writing conference would offer you, and the agent or editor booked their own ticket to the event, too. So thank them again when you close your note–say that you sincerely appreciate their interest and consideration. Because you do, of course. I myself have awkwardly signed off without a thanks and then bonked myself on the head for my poor manners. Remember, agents want to work with thoughtful writers, especially as they’re looking for a long, fruitful relationship with us.

It takes money and time to attend things like writer’s conferences and pitch sessions, and you spent a lot of energy–some of it nervous–preparing to showcase your best work. Now that you’ve gotten a request for a partial or full manuscript, give it one last glance for egregious errors, language that could use a little improvement, and craft. No agent is going to reject your email because you sent it to her one month after you spoke with her. It may not take that much time to review and polish your manuscript, but if it does, take the time. They’ll likely be impressed that you cared enough to send your very best.

No, don’t send the agent a greeting card with your partial.

July 21, 2012

PNWA 2012 Moments from Friday

The first time I came to the PNWA Conference I was by myself, staying as a guest in the man cave of a friend’s house and commuting to the conference hotel by bus. I got to the event early and stayed all day, rumbled home on uneven roads, and zonked out until it was time to repeat the process in the morning. The next year I came with my sweetheart in tow, who was 9 months pregnant at the time, so I ducked out often to grab a meal with her or check in. This year I’ve got a family with me, meaning that I’m attempting to cram baby watching time in with networking, going to panels, and pitching stories to industry folks. Now that exhaustion from two years ago seems tame in comparison.

The first time I came to the PNWA Conference I was by myself, staying as a guest in the man cave of a friend’s house and commuting to the conference hotel by bus. I got to the event early and stayed all day, rumbled home on uneven roads, and zonked out until it was time to repeat the process in the morning. The next year I came with my sweetheart in tow, who was 9 months pregnant at the time, so I ducked out often to grab a meal with her or check in. This year I’ve got a family with me, meaning that I’m attempting to cram baby watching time in with networking, going to panels, and pitching stories to industry folks. Now that exhaustion from two years ago seems tame in comparison.

Also, this is the first year I’ve attended the conference as a published author. That’s pretty rad. Even still, my self-pessimistic nature continues to knock at my mind’s door. Oh, look at your puny stack of one book. And you call yourself a writer?

I’ve written before about how I’ve sent my inner critic away on a permanent vacation. Sometimes it pops back for a rendezvous with the rest of my thoughts, and I have to shoo it away again. Yesterday it tried to set its suitcases down and I handed it a ticket to Argentina. Go see the llamas and glaciers, I said. It slumped off, pissed and dejected.

The editor’s session at yesterday’s PNWA was instructive, as always. In the room were:

Melissa Manlove, Chronicle Books–Looking for children’s books and picture books.

Renda Dodge, Pink Fish Press and Line Zero–Looking for literature as art, taking on novel length fiction and memoir, and quarterly submission to literary magazine.

Tom Colgan, Berkeley at Penguin–Looking for boy’s books: military fiction, thrillers.

Tracy Bernstein, New American Library at Penguin–Looking for adult fiction and non-fiction (mainly memoir).

Meghan Stephenson, Hudson St. Books and Plume at Penguin–Looking for how-to books, social sciences, expert non-fiction.

Peter Lynch, Sourcebooks–Looking for adult fiction and non-fiction.

Lynn Price, Behler Publications–Looking for memoir and biography, stories about overcoming problems and personal growth.

Tim Schulte, Variance Publishing–Looking for genre fiction of all kinds.

Diane Gedymin, Turner Publishing–Looking for category breakers and concept books.

J. Ellen Smith, Champagne Books–Looking for sex. Sex books, she means. She did not solicit the audience.

Some of the DOs and DON’Ts of pitching them:

Don’t say anything extraneous, just give us the story.

Show as much of the conflict and characters as possible in the pitch.

Try not to be so nervous.

Don’t give them the genre, and don’t compare your book to the extreme best sellers in the category.

Research what they’re looking for so you can pitch the right story to the right editor.

Leave room at the end for the editor to respond (for 3-minute pitches at the conference).

July 16, 2012

The Problem with Passing Privilege

I had a great blog post almost ready to launch earlier today, really I did. It was about moving my office from one location to another clear across town, and who thinks what about it, what went wrong during the move, ending with why all of this is funny.

I had a great blog post almost ready to launch earlier today, really I did. It was about moving my office from one location to another clear across town, and who thinks what about it, what went wrong during the move, ending with why all of this is funny.

And then WordPress ate it. No matter how much I cursed WordPress, I still was faced with a big blog of empty white space where once tiny words had lived. Sure, I could rewrite that post, as I’ve done before, only this blog post has decided to pop up in its place.

Instead of a trite chucklefest about who inhabits office buildings, what moving is like for a small nonprofit, and how hilarious (and nice) Walla Wallans can be in the midst of mini-crises, I’m going to write about passing privilege. I’m certainly not going for a laugh, but if you feel like having one, feel free to click on the keyword “funny” to the right and read any number of humorous experiences I’ve had. The ones where I’m in intestinal distress are the best, in my opinion.

On to the actual post.

I’ve read a number of online articles, blog posts, and rants lately about who has it worse, trans men or trans women. I’ve also come across at least a dozen pieces about who is more oppressed, transsexuals or transgender-identified people. And I have to say, with great respect to my loved and cherished friends all along the gender nonconforming spectrum/in some category of gender ID’d minority: these frames for discussion are not helping us. Yes, you are free to disagree with me, and call me out, claim I’m speaking with the voice of the entitled, yes. I still would like to pose some questions about several of the presumptions in how this idea of oppression is framed. As an example, I’ll point to established cultural theory from a principled thinker.

Patricia Hill Collins was an early advocate of intersectionality, looking at how multiple oppressions reveal insight into the institutions that mete out that oppression. In this frame, jockeying for position as the most oppressed is considered an unhelpful means of taking hegemony to task. Instead, she looked to a careful examination of white supremacist capitalism and its intersections with race, gender, and class. Attached to a history of disempowerment and slavery, and connected up to modern ideas about who black women are (in the way of cultural stereotypes and problematic role models), Collins inquired about how a group of oppressed people could rearticulate not only an empowering cultural identity, but also use that identity in a material way–to achieve improved/liberatory lives as a class of people.

If we give up on the concept of finding the most oppressed community, some new possibilities open up. Power, for example, is no longer absolutely granted or absolutely forbidden. For another way of looking at it, power is never pure, not in this social system of ours, anyway. Power and its attending privilege is wrapped in social and material history, positionality, and intersectionality with other markers of identity. So when we talk about how trans men are “better off” than trans women (especially, as we’re often reminded, than trans women of color), what do we mean? We mean when those trans men have passing privilege, for one, and for another, we mean that masculinity is regarded as so powerful that even people who did not come into the world as men but who aspire to it now are more privileged than people who are leaving masculinity behind. While it’s true that individual trans-identified and/or masculine-identified people may hold horrible or bigoted views of feminine-identified people, we should not insist this is an issue of the entire community. At the very least, such insistence is yet another demonization of a group of oppressed people. Do we really want to go there in forming our progressive politic?

Let’s also examine this idea about passing privilege as evidence that the question of the most oppressed is problematic. In my personal experience, I spent 15 years as a masculine-looking, female-identified person who was subjected to ridicule, harassment, and physical attacks in both my personal life and at my workplace because I didn’t have normative gender expression. When I figured out the trans thing and began to transition, those events actually increased in frequency until a certain point. Let’s call it the passing tipping point. What passing was for me, in my experience, was a series of short moments in which someone read me as male instead of female. In a given day toward the beginning of my medical transition, they amounted to something like 5 total minutes. Not that I was displeased with 5 minutes! But more than a year later, I still had coworkers asking each other behind my back what my sex was. In that 2+ years of getting to 95 percent read as male every day, how should we understand that passing privilege?

In many of these conversations, passing privilege is thrown around reductively, as if it’s a permanently ascribed status to a particular body in culture. But the very word “passing” describes its impermanence. It also points to the difference between one’s history and one’s current–even momentary–social positionality. In the arguments about who has it worse, there is little nuance given to passing. When did a trans man leave behind his female socialization and simply become an entitled, stage-stealing, unfeminist part of the problem? The first moment he’s read as male? The fifth? After the second month of full-time passing status? What do we make of him when he’s in public with his family and they purposely mispronoun him so others know his transness? Do we really want to argue that his social position is predicated on one moment over another? Or is there a more productive way to understand the navigation between passing and not passing, or “read as oppressed” and “read as privileged” shifts that many transfolk experience?

I’ve said before that most dichotomies are impoverished, inaccurate, and lead us into supporting the status quo instead of deconstructing it. Human beings in western culture have a stubborn insistence on our individual exceptionalism (most people are this way, but not ME), and a lack of solid memory. It can be difficult to spend more time listening than speaking when a person transitions into occupying a male identity, after years of hearing in those wonderful women’s studies classes that women should take up more space. I know as a transsexual that it’s damn hard not holding one’s pre-transition life against oneself for the rest of one’s existence, but this is where we need to be kind to ourselves and others.

Part of the usefulness of intersectionality is that it unpacks how different communities on the margins are pitted against each other, by the culture and institutions of the controlling ideology, and in furtherance of ideology’s continued hold on all of us. If white women and black women are both (but differently) harmed by sexism and misogyny, it helps the hegemonic system if they are suspicious of each other. When we debate whether trans women or trans men have it worse, we necessarily remove accountability from the system of oppression and point fingers at each other, and that leads us to some questionable conclusions–in this rubric, trans women are incapable of leaving behind their male privilege, and trans men are incapable of being anything other than subsumed by that same male privilege.

If we were to look at how culture differently positions trans women and trans men (and in greater context, transsexuals and people under the transgender umbrella), we could identify a more comprehensive theory of gender. Certainly the paranoia among some second-wave feminists that trans women are a danger to nontrans women puts forth a different construction about gender than comments from conservatives that trans men are really confused women who should be raped back into gender conformity. I am not arguing that trans women aren’t murdered in higher numbers than trans men, but I would rather ask why that’s happening and how we can change that reality than use it as evidence that trans women are the most oppressed community.

Perhaps one of the biggest questions here is this: how do traditional ideas about masculinity and femininity adversely mark gender non-conforming people, and how can we re-understand these gender abstractions to our and culture’s betterment? After 40 years of women’s liberation and gender theory working against the idea of “natural,” essential gender, why are those concepts still so prevalent?

July 13, 2012

Daniel Tosh Is Not the Problem

Last week, a brouhaha erupted on the Internet after Daniel Tosh, a lackluster comic and host of Tosh.0 on Comedy Central made a joke about rape. Or rather, he attempted such a joke, knowing full well that somebody out there in the world, if not his audience, would find it unfunny and offensive. Many smart people have written about why there’s no place in comedy for jokes or comic routines on the subject of rape, others have waxed eloquent on where this moment intersects with the First Amendment, but I’d like to expand the discussion here.

Last week, a brouhaha erupted on the Internet after Daniel Tosh, a lackluster comic and host of Tosh.0 on Comedy Central made a joke about rape. Or rather, he attempted such a joke, knowing full well that somebody out there in the world, if not his audience, would find it unfunny and offensive. Many smart people have written about why there’s no place in comedy for jokes or comic routines on the subject of rape, others have waxed eloquent on where this moment intersects with the First Amendment, but I’d like to expand the discussion here.

The issue of what’s funny and where the boundaries of taste and appropriateness in comedy comes up often. Stephen Colbert recently apologized for likening the food industry’s infamous pink slime to transsexuals. Tracy Morgan was taken to task for saying during a stage routine that he’d kill his own son if he found out the kid was gay–when asked about the lines, he remarked:

I don’t “f*cking care if I piss off some gays, because if they can take a f*cking d**k up their ass … they can take a f*cking joke.

Adam Sandler’s last movie, let’s face it, was one big affront to LGBT people and not too many other folks thought it was funny. It swept the Razzies and Rotten Tomatoes for bad filmmaking.

Am I trying to steal the attention away from rape survivors? Um, no. But maybe it’s time we took a look at a bigger framework here. Let’s posit that popular culture has a relationship to actual lives–after all, we spend time, money and energy on engaging with popular culture, we talk to our friends about what we’ve seen (OMG, Breaking Bad was awesome last night!), and we anticipate popular culture like we anticipate spending time with people we know. But more than that, we use popular culture as a shared, communal experience (e.g., the water cooler discussion), and we debate the issues and subjects popular culture offers us.

Finally, popular culture is, by design, attempting to get a response from the audience. Comics may be looking for laughs and not hecklers, sure, but they do anticipate a reaction–that’s what jokes are for. If the makers of popular culture’s products weren’t invested in the audience’s response, they wouldn’t look to publish, televise, or release their work to the public. Thus if people like our aforementioned comics are going to make careers and livings out of putting their products into the public space, then they have also opened themselves up to critique.

So what is there to critique? Well, as already noted, popular culture’s content has effects on the people living in culture. We form and develop opinions based on the world around us, and that includes the movies, comic routines, televisions shows, Web sites, etc., that we consume. There may not be a simple formula or path from rape joke to an actual sexual assault, but there certainly are material effects from suggesting, even jokingly, that a group of nearby men should gang-rape a woman in their midst. And I would argue that when Stephen Colbert suggested that there were so many hormones in pink slime that it deserved a place in the transsexual community, he reduced the image of transfolk TO the hormones they take. What does it mean to do that? Well, for one, it’s dehumanizing. And I know I don’t need to explain why dehumanizing an entire community is a bad thing, right? (But it’s also inaccurate–transsexuals aren’t on more hormones than anyone else, they’re just on the opposite ones, which shuts down their original sources of hormones. In fact, many trans people I know are on low doses once their initial transition is over.)

Representation matters, insofar as mainstream culture offers more exposure of people on the margins of society than the people themselves do. After all, marginalized groups often must go through some institution of popular culture to get any kind of widespread exposure, be it the press, a gatekeeper from the industry (like an agent or editor), a publisher or producer, or a spokesperson who then interacts with…an arm of popular culture. Even if social media has carved out some paths around traditional media organizations, popular culture rushes in [sic] and reinterprets these moments, picking up Twitter feeds and Facebook posts and vaulting them to media outlets on the Web, and so forth. In many ways, negative feedback to the producers of content in popular culture represents one of our best ways–and it’s a democratic way at that–to change those representations for the better. I would hope that with a curtailing of lynch, rape, and murder jokes, that more people would glean the idea that these are unacceptable acts, and conversely, fewer people will put up with jokes premised on such things. After all there is more than enough space in the sphere of popular culture for jokes that are truly funny and that don’t rely on suggesting individuals harm each other.

No, Daniel Tosh is not the problem. He’s the symptom of a larger, structural problem in understanding and representing vulnerabilities among different groups of people, but it’s also the case that he’s made his career on laughing at people in one of the most juvenile ways possible. Perhaps someday so many of us will see that his humor is so bereft of interest and cleverness that popular culture itself will turn away from giving him any air time.

July 8, 2012

The Limitations of Dichotomies

[image error]I don’t pretend that this is news, for I first learned about false dichotomies in 1991, as the prequel war began in Iraq. Actually the rhetoric around that conflict gives good context for this discussion, because it was presented by the media to all of us as a fight between good and evil, the granddaddy of all dichotomies. George Bush the Elder seemed not quite the thousandth point of light to we idealistic college students, and although Saddam Hussein clearly wasn’t a benevolent leader for his country, many of us questioned the purity of malignancy that our government suggested he represented.

Friends came back from Desert Storm with nagging or incapacitating illnesses that were written off as psychosomatic, while the faces of so many dead Iraqis scarcely made the evening news. We told ourselves that it was a good thing the whole event was over in three weeks, at least until several years later when Colin Powell explained to the United Nations that this was why we needed to return and finish off the regime once and for all.

The story about the good forces in the world and its evil counterparts is compelling, certainly. It’s also got longevity in culture because its very narrative design is never-ending. Good and evil are intertwined, at battle forever. And by extension, so is every other dichotomy that has positive and negative valences. Maddona/whore. Rich/poor. Country/city. Bully/bullied.

But these either/or concepts catapult us into dangerous territory. If we take up the issue of bullying only within this “side versus side” lens, we lose a large portion of people’s lived experience in our analyses. Many individuals have been bullied and also bullied someone else. In thinking about anti-bullying policy, how would an understanding of the gray boundary of people’s behavior change how we respond to bullying wherever it is found? Last month a video of students mocking a school bus monitor–a female senior citizen, in this case–went viral, and it is a good example of seeing that bullying doesn’t necessarily always follow an expected set of actors. How, for instance, does the idea of bully/bullied unravel when we look at the Columbine High School massacre, since those perpetrators were acting out against chronic harassment from other students?

Dichotomies also don’t take into account that behavior occurs over time. Humans are more than capable of shifting their positions in culture and interpersonal relationships, using their frustration on the margins in one community and enacting it against others they perceive as weaker in another location. Such tendencies are well documented in psychology and social psychology, perhaps most famously by Milgram’s experiments on people’s willingness to hurt others when confronted with draconian authority. What was a mild mannered person in one moment, before sitting down at a machine that would deliver electricity to another person, becomes, over a series of moments that desensitize that person’s conscience, an abuser. If bullies aren’t “born” but are created through perverse motivation and circumstances, why continue to give the dichotomy credibility? Why are we willing, in the face of empirical evidence that the dichotomy is impoverished and wrong, to go about using it when setting anti-bullying policy?

Perhaps it’s not politically possible to write policy that understands that children can occupy either position, or vacillate between those poles. Or maybe we’re not comfortable with discussing how teachers, administrators, supervisors, and school board members exacerbate bullying. I suppose it’s hard to take on issues of accountability in communities where everyone knows each other and have history with each other. But for the sake of our future generations, don’t we owe it to them to try?

While we’re at it, crafting new ideas about how bullying occurs and what consequences it has for the individuals affected by it, how about we also eschew other dichotomies? I’d like to start with these–innocent/guilty, and oppressor/oppressed. Okay, okay, I’ll give them their own proper posts.

July 5, 2012

Writing Through Stress

We adult-type people recognize that life is hectic, tilted toward entropy, and full of aggravation. Big moments, unexpected problems, and the aforementioned garden variety pressures get us stressed out, and I know that is an understatement. But the writing (and the dinner making, diaper changing, phone call returning, toothbrushing) must go on. Of course nothing resolves stress like actual problem solving, but let’s presume that some stress is ongoing or can’t be eliminated before one needs to spend quality time with their project. Just what is in my particular box of tricks? For writers like me, having a toolkit of tactics to deal with chronic stress so the creative whatnot can flow is critical stuff. Check out the following:

We adult-type people recognize that life is hectic, tilted toward entropy, and full of aggravation. Big moments, unexpected problems, and the aforementioned garden variety pressures get us stressed out, and I know that is an understatement. But the writing (and the dinner making, diaper changing, phone call returning, toothbrushing) must go on. Of course nothing resolves stress like actual problem solving, but let’s presume that some stress is ongoing or can’t be eliminated before one needs to spend quality time with their project. Just what is in my particular box of tricks? For writers like me, having a toolkit of tactics to deal with chronic stress so the creative whatnot can flow is critical stuff. Check out the following:

Do something that relaxes you, and have time set aside for writing immediately thereafter–Book a massage, read something by your favorite author (always also good for inspiration in general), go for a walk to release some stress-killing endorphins, and while you’re still in the afterglow, tackle your writing project. If you’re still staring at the screen in frustration, hit up other sections of your brain by picking up a pen and making notes, jotting down back story, writing in longhand a description of the protagonist, and so on. Often one successful creative jolt fuels the next.

Set the music–I try to ascertain, as quickly as possible, if I need a familiar or a new song to kickstart a writing session. That’s not to say I always write to music, but when I need it, I need it, and I don’t worry about why or what it means. Remember, the real work comes in the long editing and rewriting phase. I select music that counters the forces dragging me down; if I’m overexcited, I decelerate down my own personal I dunno with slow grooves, and if I need to bring up my energy level, well, you get the idea. I do have some go-to play lists for those days when I can’t think about anything too much and I need to prioritize diving into the work.

Change up the scenery–I acknowledge that many people have lovely writing studios or work areas, and I hope to be one of those people in my future. For now, I am a minimalist, preferring to work on a laptop or with a notebook, and keeping only a pen, index cards, and a refreshing beverage at my side. I swear this lets me switch up my writing environment when it stops encouraging words to come out of my head. Music helps take me out of my own headspace and helps me capture the world I’ve created, and that is exactly where a writer needs to reside.

Get more sleep, if possible–Sleeping enough helps our brains parse through the chemicals that make us feel stressed out, so trying to get 7 or 8 hours of shut eye a night helps set us up for future success. I recognize such things aren’t always possible–I’m a father of a 10-month-old, after all–but don’t give up on sleep. If you need to assess your daily schedule to figure out how to make more time for sleep, give it a try. I’m about to make a shift this fall to scheduling my writing time in the early morning before the Wee One wakes (I’m sure it will be the subject of more than one blog post). And yes, it will necessitate an earlier bedtime for yours truly, probably soon after I put the baby down for the night, in fact.

Switch projects–Hey, it might not be your stress level that is dragging down a given project; instead, maybe it’s not be the right project for this time in your life. Perhaps a story about loss isn’t approachable when one is mourning the death of a close loved one, for example. If we’re dedicated writers, we will in all likelihood get back to a story that demands to be finished. It’s okay to change gears and work on something else, and not only is it okay, it’s common. I mean, you’re not common, of course not. But you’re in good company if you trunk a project for a while and pick up a new one that resonates better with your emotional or energy needs.

I hope these are helpful suggestions; I’d love to see other ideas in the comments. What do you all do when you need to produce but are on your last nerve?