Duncan Green's Blog, page 172

January 26, 2015

When will we reach Peak Inequality?

Post Davos, Max Lawson, Oxfam’s Head of Global Policy and Campaigns, is still trying to get his head around the inequality stats

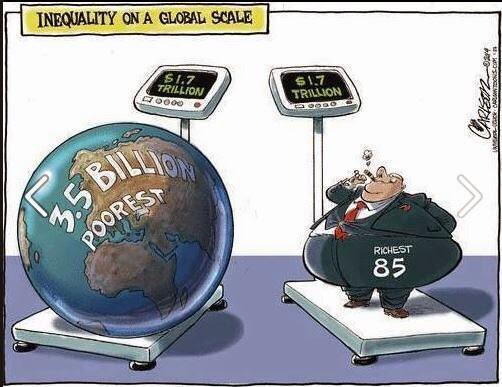

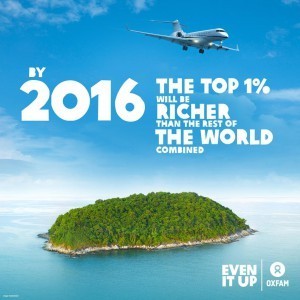

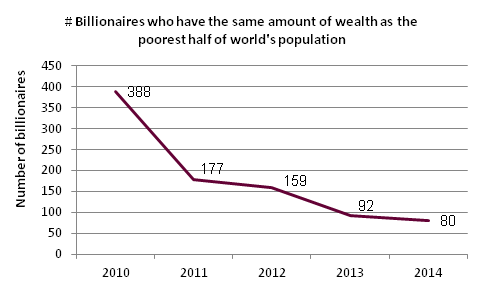

Last year it was 85 people; this year it’s down to just 80 individuals who have the same wealth as the bottom 3.5 billion people. By next year the top 1% will own more wealth than the rest of us put together.

This of course makes you wonder when it will end. When will we reach peak inequality? Just how bad is it going to get? Not hard to imagine the Guardian front page in January 2020: ‘Oxfam Reveals: One man now owns the same as half the world’. Perhaps with a sub story about how Davos has had to downsize as wealth is now so concentrated that 2,500 delegates was starting to look a bit petit bourgeois.

Inequality is already at ludicrous levels. By some measures worse than it has ever been in the United States. Worse than in the time of the robber barons, or Gatsby. Many other nations are headed in the same direction. I think partly there is a cultural and perceptual time-lag, as we struggle to catch up with the economic facts. Many impacts are only just starting to be felt, as Piketty points out, such as the return to prominence of inherited wealth. What is clear is that unless something changes fast, for our children, Downton Abbey will be a current affairs soap opera, and families will wistfully watch carefully crafted period dramas about meritocratic government schools in the 1970’s where clever poor kids were still able to go to university paid for by taxes on the rich.

Ah those were the days – it’s 80 now

I didn’t realise this, but apparently one of the benefits of a Rolex is it doesn’t need batteries; the motion of your wrist keeps the watch going. This presents a problem however when you own more than one. So those clever Swiss boffins have invented a Rolex ‘Rocker’ for you to safely store your Monday Rolex whilst sporting your Tuesday one. I can think of no better symbol for the insanity of today’s world. Hundreds of millions of people will go to bed hungry tonight; not just in countries in Africa, or in Asia, but in Spain, the UK and the United States. Meanwhile Rolex is doing a roaring trade in rockers.

There at least seems to be a consensus emerging now that this insanely skewed distribution of wealth is harming us all and jeopardising our collective future. It is threatening our economic progress, corrupting our governance, corroding our societies and constructing a dystopian and scary future. Unless we reach peak inequality soon, we are in deep trouble.

In this there are huge parallels with climate change and the desperate need to reach peak carbon too. We need to rapidly start building more equal and sustainable societies for our children. Instead we seem to be accelerating in the opposite direction, burning more carbon and becoming more unequal than ever before. As soon as my sons are old enough. I have no doubt they will berate me and my generation for not doing more to stop them inheriting a broken, burning world.

Naomi Klein believes the connecting causal factor is market fundamentalism, driven by the same small, organised right wing global elite that is causing both the inequality and climate crises. Duncan is far more optimistic, and thinks we have passed ‘peak neo-liberal’. I am not sure what I think, but it does seem to me that the policies implemented during the period of capitalism when the most progress was made in tackling inequality, policies such as public provision of services, public ownership and subsidy of industry, progressive taxation of rich individuals and corporations, strong trade unions and labour rights, full employment, universal welfare states, strong limits to intellectual property – are still pretty much frozen out of current debates. There have been some glimmers of hope recently with the IMF saying that ‘at times redistributive policies can in fact not be harmful to growth’- but the fact that this limited and admission made a headline in the Financial Times itself shows how much further we have to go to return to common sense.

Last time we had peak inequality, it took a Russian Revolution, a great depression and two world wars before governments introduced progressive  policies and delivered decades of falling inequality and shared prosperity. This time around, we must pray that sense prevails less painfully.

policies and delivered decades of falling inequality and shared prosperity. This time around, we must pray that sense prevails less painfully.

What is exciting is that some countries are already bucking the trend – most recently Indonesia, where the new popular progressive president Jokowi is introducing universal health coverage and the largest social protection scheme in the world, paid for in part by cutting regressive subsidies on fuel. Many countries in Latin America are also making strong strides in tackling inequality. Stories like that fill me with hope.

The lesson is consistently clear: progressive, anti-inequality policies are implemented to appeal to the majority. They happen when the balance of people power outweighs plutocracy. So whilst debates in the dining rooms of Davos are all very well, the precise date of peak inequality will be decided on the streets and voting booths of Athens, Jakarta, London and Mexico City.

January 25, 2015

Links I Liked

Kids in Nairobi’s Kibera slum take on the land grabbers to defend their playground against cops, dogs & tear gas. And win, at least for now.

Last week was Davos week: Oxfam’s Winnie Byanyima starred in a truly brilliant BBC debate on inequality (Christine Lagarde was the other standout, other panellists were Robert Schiller, Mark Carney, Martin Sorrell and Klaus Kleinfeld). Try and find an hour to watch it.

Gender inequality got a good airing by Lagarde, and Action Aid chipped in with a new report estimating that “women in developing countries wouild be $9 trillion better off if pay and access to paid work were equal to mens’”

At a more micro level there are ‘practical steps you can take to reduce sexism in economics’ [h/t Claire Melamed] and (if you’re a man) you can join me in signing up to Owen Barder’s pledge not to appear on men-only panels (I guess you could argue that all women have already signed….)

Owen’s had a good week, with this forensic rebuttal of criticisms of the way DFID hit its 0.7 last aid target last year. Must read for UK aid wonks.

This year seems to be hitting peak summit (is that a thing?). Kevin Watkins discusses breakthroughs v epic fails on the Financing for Development, Sustainable Development Goals and Climate Change summits coming our way

Nice sign in London’s Kew Book Shop – every other independent bookstore in the world, you know what to do …….

Nice sign in London’s Kew Book Shop – every other independent bookstore in the world, you know what to do …….

January 22, 2015

Why Bill and Melinda’s Annual Letter is both exciting and disappointing

Judging by his latest annual letter, if you could bottle and sell Bill Gates’ optimism, you’d probably make even more money than he has  from software. In what they call a ‘big bet’ (actually, more like a prediction), the letter sets out Bill and Melinda’s personal version of some post-MDG goals for 2030 (Charles Kenny sees it as an implicit criticism of the official UN process on that):

from software. In what they call a ‘big bet’ (actually, more like a prediction), the letter sets out Bill and Melinda’s personal version of some post-MDG goals for 2030 (Charles Kenny sees it as an implicit criticism of the official UN process on that):

‘We think the next 15 years will see major breakthroughs for most people in poor countries. They will be living longer and in better health. They will have unprecedented opportunities to get an education, eat nutritious food, and benefit from mobile banking.

These breakthroughs will be driven by innovation in technology—ranging from new vaccines and hardier crops to much cheaper smartphones and tablets—and by innovations that help deliver those things to more people.’

That progress includes:

‘Child deaths will go down by half

Cutting the number of children who die before age 5 in half again

Reducing the number of women who die in childbirth by two thirds

Wiping polio and three other diseases off the face of the earth

Finding the secret to the destruction of malaria

Forcing HIV to a tipping point

Farming: Africa will be able to feed itself

Banking: Mobile banking will help the poor radically transform their lives

Education: Better software will revolutionize learning’

The final section of the letter is a ‘Call for Global Citizens’ who will ‘take a few minutes once in a while to learn about the lives of people who are worse off than you are. You’re willing to act on your compassion, whether it’s raising awareness, volunteering your time, or giving a little money.’

That’s all great, and particularly on issues such as climate change, we need that global citizens’ movement asap. We also need it to rein in the arms trade, predatory corporates and tax evasion, which aren’t mentioned (although at Davos this week Bill urged his rich colleagues to pay their taxes).

But even so, I read the letter with a growing sense of uneasiness. The Gates Foundation is full of incredibly smart, dedicated people, who must know from bitter experience that getting all this progress entails both understanding and working with the messy realities of power, systems, politics and institutions – the stuff that I write about ad nauseam on this blog. So does it matter that the Letter completely ignores them? Instead what it offers is a technocrats’ charter – a parallel universe in which new tech will solve ill health, climate change, illiteracy and just about everything else – this is a ‘thinking and working politically’ – free zone. Two reasons why that matters (there are many more).

Instead what it offers is a technocrats’ charter – a parallel universe in which new tech will solve ill health, climate change, illiteracy and just about everything else – this is a ‘thinking and working politically’ – free zone. Two reasons why that matters (there are many more).

Firstly, development is above all about domestic politics and the interaction between citizens and states. If the Ministry of Health is only interested in looking after one part of the population, or its senior civil servants are all running private businesses out of their offices, no amount of new tech is going to help much – only politics and the struggle for accountability and better government can do that. Even in terms of resources, aid is becoming less important compared to domestic taxation and mineral revenues, neither of which get a mention (nor does inequality). Instead, the letter feels like a throwback to a ‘Make Poverty History’ frame that depicts aid, technological progress and philanthropy as the main drivers of progress. They aren’t.

Second, conflict is a massive barrier to all these potential gains, but doesn’t get a mention (maybe it’s too messy, no tech fixes?). The only reference to DRC laments its lack of paved roads, but passes over the chronic violence that has claimed millions of lives.

Is it OK to airbrush out the messiness of real developing countries, turning them into an imaginary peaceful, low income recipient of technological progress, run by well-intentioned philosopher kings (preferably elected)? I had an enjoyable argument with an Oxfam colleague on this who responded ‘why does the Foundation need to ‘do development differently’ if they are achieving successful results in addressing issues of poverty, illness, food security, technological innovation, and increased citizen voice?’ I think it matters because encouraging an apolitical mindset in the aid community has already proven to be a really bad idea, setting them up to fail and secondly, because giving the public only half the story (or less) is setting the aid business up for a bigger backlash when things go wrong (as they will, at some point).

And as poverty increasingly becomes concentrated in fragile and conflict states, the gulf between the Letter’s can-do optimism and an increasingly fragmented reality is only going to grow. The Gates Foundation people know all this, but the letter doesn’t acknowledge any of it.

Does that matter? Isn’t this a letter that is supposed to galvanize public opinion (primarily in the North) and show what is possible? Given Ebola, Syria etc, we can certainly do with a Charles Kenny style reminder that overall, things are indeed Getting Better. Maybe so, but my gut feeling is that airbrushing to this extent does the cause a disservice, and is bound to come back and haunt us one day. I think Bill and Melinda should level with people. What do you think?

Here’s Bill and Melinda in cartoon versions summarizing the letter

January 21, 2015

Why ‘what’s your endgame?’ is a better question for aid agencies than ‘how do we go to scale?’

Maybe it’s partly an age thing, but a lot of senior people in the aid business seem to obsess about scale. What’s the point of running a few projects, however

Going to scale can end in tears

successful? No, the only worthwhile end is ‘going to scale’, affecting the lives of millions of people, not a few hundred. It’s understandable and laudably ambitious, but it can have some bad side effects:

It can lead to an outbreak of ‘best practicitis’, ‘rolling out’ cookie cutter programmes in dozens of countries, when all the Doing Development Differently work shows that approach doesn’t work – solutions have to be crafted by local actors, and will differ according to context.

It can lead to a ‘bigger is better’ rush to boost income, leading to jumping into bed with bad guys, or reversing decades of progress in reducing the use of emotive ‘poverty porn’ fund raising images.

It promotes a ‘we know best’ arrogance that ignores local solutions.

But a brilliant piece in the Stanford Social Innovation Review calls for a rethink and proposes some really useful ways to go about it:

‘Most nonprofits never reach the organizational scale that they would need to catalyze change on their own. High structural barriers limit their access to the funding required to grow in a significant and sustainable way. Given those barriers, it’s time for nonprofit leaders to ask a more fundamental question than “How do you scale up?” Instead, we urge them to consider a different question: “What’s your endgame?”

An endgame is the specific role that a nonprofit intends to play in the overall solution to a social problem, once it has proven the effectiveness of its core model or intervention. We believe that there are six endgames for nonprofits to consider—and only one of them involves scaling up in order to sustain and expand an existing service. Nonprofits, we argue, should measure their success by how they are helping to meet the total addressable challenge in a particular issue area. In most cases, nonprofit leaders should see their organization as a time-bound effort to reach one of those six endgames.

So what is your endgame? Is it “continuous growth and ever greater scale”? In light of the enormous challenges that exist within the social sector, that is an easy and compelling answer for nonprofit leaders to give. But it may not be the right answer.’

And here’s their six endgames, and their implications for how we work – well worth reading and thinking about this. I’d love to hear your reactions.

January 20, 2015

14 ways for aid agencies to better promote active citizenship

As you may have noticed, I’ve been writing a series of 10 case studies of Oxfam’s work in promoting ‘active citizenship’, plus a synthesis paper. They  cover everything from global campaigns to promoting women’s leadership to labour rights. They are now all finished and up on the website. Phew. Here’s the accompanying blog which summarizes the findings of the exercise (with links to all the papers). Huge thanks to everyone who commented on the draft studies when they appeared on the blog.

cover everything from global campaigns to promoting women’s leadership to labour rights. They are now all finished and up on the website. Phew. Here’s the accompanying blog which summarizes the findings of the exercise (with links to all the papers). Huge thanks to everyone who commented on the draft studies when they appeared on the blog.

Programme design

1. The right partners are indispensable

Whether programmes flourish or fail depends in large part on the role of partners. Usually this means local NGOs or civil society organizations, but sometimes also individuals, consultants or academics. Good partners bring an understanding of local context and culture (especially important when working with excluded minorities such as the tribal peoples of Chhattisgarh). They often have well-developed networks with those in positions of local power and will carry on working in the area long after the programme has moved on.

2. Start with the ‘power within’

Promoting active citizenship means building the power of citizens, starting with their ‘power within’ – their self confidence and assertiveness – especially in work on gender rights. In the case of We Can in South Asia or Community Discussion Classes in Nepal, building this ‘power within’ was almost an end in itself. Elsewhere, citizens went on to build ‘power with’ in the form of organizations that enabled poor and excluded individuals to find a strong collective voice with which to confront and influence those in power. This approach has led to some impressive progress in what are often the most unfavourable of circumstances (women’s rights in Pakistan, civilian protection in Eastern Congo).

3. Build the grains of change

Active citizenship is often built on collective organization. But building such organizations is about much more than simply promoting protest movements. Historically, social movements have been ‘granular’. Short term surges in active citizenship are actually made up of myriad ‘grains’ – longer- lasting organizations that span everything from faith groups and trade unions, to sports clubs and funeral societies. Success in building active citizenship usually involves identifying and working with existing grains, such as trade unions in Indonesia, or building new ones, like the Women’s Leadership Groups in Pakistan or the Community Protection Committees in the DRC. These groups are best placed to weather the storms of setbacks and criticism, and provide the long term foundations for activism, whether as channels of information, sources of mutual support, or as expressions of collective power.

lasting organizations that span everything from faith groups and trade unions, to sports clubs and funeral societies. Success in building active citizenship usually involves identifying and working with existing grains, such as trade unions in Indonesia, or building new ones, like the Women’s Leadership Groups in Pakistan or the Community Protection Committees in the DRC. These groups are best placed to weather the storms of setbacks and criticism, and provide the long term foundations for activism, whether as channels of information, sources of mutual support, or as expressions of collective power.

4. The importance of broad alliances and coalitions

Who should the grains engage with? Change is often achieved by engaging and, if possible, allying with a range of stakeholders to pursue a particular issue. A rigorous initial power analysis is essential to reveal the range of possible allies, but in general, the broader the range, the better. For example, those working on violence against women and women’s empowerment made it a priority to work with men. Building relationships with conservative evangelicals and Republicans in the Deep South paved the way for success in the campaign to ensure the fines from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill truly benefited local communities.

5. Individuals and relationships matter

Processes of change are driven by real people, not faceless masses. In practice, there will be some individuals on both sides of the negotiating table (or barricade) who are more able and willing to understand the dreams and demands of all sides, and more interested in seeking change and compromise. Other individuals will have ‘invisible power’ in the shape of critical behind the scenes influence. Identifying, understanding and building relationships with these people, whether they are adidas buyers in Indonesia or military commanders and traditional leaders in DRC, is essential.

6. Building active citizenship takes time

Gathering the grains into a social movement is painstaking work, requiring sustained investment of time and empathy. Many of the timelines for the case studies show work stretching back over a decade or more – far longer than the typical NGO funding arrangement. This poses real challenges both to funders and ‘implementers’. One approach is to agree a 10–20 year ‘envelope’ for a programme, which then shames the 2–3 year modules within it that are required to seek funds.

Choosing promising targets

7. Quick wins

Embarking on a ten year process with no certainty of victory is a daunting task. Successes, however small (for example a brother no longer insisting that  his sister brings him food), can boost spirits and sustain people for the long haul. This is even more the case when, as with the tribal peoples of Chhattisgarh, there have been few previous examples of successful dealings with the authorities.

his sister brings him food), can boost spirits and sustain people for the long haul. This is even more the case when, as with the tribal peoples of Chhattisgarh, there have been few previous examples of successful dealings with the authorities.

8. Implementation gaps

While some of the programmes recorded in the case studies lobbied for new laws, many targeted the gaps between existing rules and their implementation. On women’s empowerment, rules on quotas of women in various decision-making bodies in many South Asian countries (such as Nepal) offered an enticing target. In Indonesia, Oxfam made an explicit decision to work within the existing legal framework, out of recognition of its identity as an outside organization.

9. Windows of opportunity

Change is seldom continuous. Long periods of stagnation and stasis are punctuated by sudden spikes of activity. These are often linked to ‘shocks’, whether political, economic or environmental. New constitutions, decentralization processes, elections, floods in Pakistan, even an oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, have all served to shake up existing power relations and alliances, and make new movements and conversations possible. Successful programmes plan around such windows where possible or spot and respond to them rapidly as new ones open up.

Challenges and Weaknesses

10. Working with faith groups

Many people living in poverty place enormous trust in religious institutions, which are often central to the construction of norms and values, including those that promote (and sometimes inhibit) active citizenship. In some of the case studies, programmes reached out to religious leaders and faith groups. For example, in the US, conservative evangelicals played a crucial role in ensuring that the response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill supported local communities. In Tanzania, the Chukua Hatua programme belatedly recognized and built on the prevalence of religious leaders among its ‘animators’, who are trained to catalyse change in their community. The Aurat Foundation in Pakistan arrived at a nuanced and well thought through engagement approach that included working with progressive Islamic scholars, but avoided religious leaders.

In other cases, however, a ‘secular default’ in Oxfam’s work has meant not engaging properly with faith leaders on issues such as the Arms Trade Treaty, which would on the face of it seem a natural and promising arena for collaboration.

11. Can you do active citizenship without addressing jobs and income?

Trying to make income-generating schemes work can devour the time and resources of a programme, but ignoring the importance of income risks alienating people who are desperate to improve their material conditions. Moreover, as Raising Her Voice (RHV) found, activism costs at least some money, and low incomes can be a deterrent. In Pakistan, the RHV programme and its Women’s Leadership Groups from the outset worked to link women to sources of credit and grants. In DRC, initial efforts to include income generation were abandoned because they didn’t work.

Serious change is seldom entirely peaceful, but conflict carries huge risks for people living in poverty, whether physical or material (for example, being cut off from sources of patronage). In the most high risk environments (Pakistan; DRC; We Can South Asia), programmes opted explicitly for a ‘softly softly’ approach. Elsewhere, an insider/outsider combination of cooperation with allies, mixed with confrontation and protest were necessary and proved effective. For example, in Nigeria, successful advocacy for the passing of the 2013 Violence Against Persons Prohibition Bill, led by RHV partner WRAPA, included hiring a former legislator to navigate the corridors of power, text message barraging of Ministers and highly publicised mock tribunals.

13. Formal politics

The world is not neatly segregated between acts of citizenship and formal politics. The two inevitably leach into each other, posing challenges to programmes who are concerned about ‘contamination’ from the formal political world, which in many countries is associated with clientilism, corruption and coercion. In Nepal, political parties quickly identified and tried to recruit fledgling women leaders – in the end the RHV Nepal programme had no option but to try and equip them with the means to judge and manage the interaction. In Pakistan, the programme embraced formal politics from the beginning, building support networks between women political leaders.

14. Funding, evaluation and value for money

Many of the programmes in the case studies relied on ‘good donorship’ – donors that were willing to take risks. In Tanzania, DFID funded an experimental approach without pre-agreed outcomes. The success of RHV grew partly from a five year funding agreement (also with DFID), which allowed time for experimentation, failure, learning and redesign.

The pressure to demonstrate results and value for money puts particular pressures on active citizenship work, where attribution is hard to prove and most (if not all) evaluation is qualitative (often seen as second best by donors). The key seems to be in developing genuinely rigorous approaches to evaluation and ‘counting what counts’.

And here’s a lovely video from the Nepal case study that makes it all a bit more human

https://www.youtube.com/watch?wmode=t...” width=”WIDTH” height=”HEIGHT” >

January 19, 2015

Links I Liked

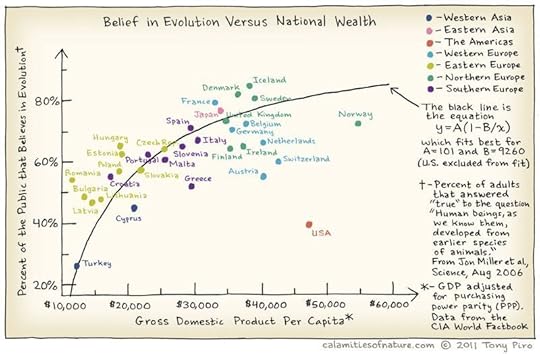

America the Outlier. Belief in Evolution v national GDP per cap. Spot the odd one out. I’ve seen similar graphs on life expectancy v health spending. Any other candidates?

The Napoleonic war, infant industry protection and herpes. Vintage Chris Blattman

Then there’s some bad news

Trade Bullies? EU holds Kenya’s big and job-creating flower industry hostage to force it to open its markets and sign an EPA trade agreement

Q: 5 years on, what is legacy of the Haiti response? A: No idea. Simon Levine on the short termism of humanitarianism.

And Mixed News

You’re Fired! UN Global Compact expels 657 member companies for failing to produce reports on compliance for two consecutive years (well at least they’re doing something about it) [h/t Richard King]

15 African countries have national elections in 2015. But remember that according to Paul Collier, conflict risk peaks just before and after elections brookings.edu/blogs/africa-i…

15 African countries have national elections in 2015. But remember that according to Paul Collier, conflict risk peaks just before and after elections brookings.edu/blogs/africa-i…

But quite a bit of good news too

Mainstream US Democrats see Robin Hood Tax as central to “a move towards establishing a 21st century structure for financial markets.” [h/t Gawain Kripke]

New and hypnotic Hans Rosling bubble graph on declining fertility by country (up to 2013)

Statistical evidence that IMF debt relief reduced child mortality in Africa.

Finally, Charlie Hebdo continues to reverberate.

‘As a Muslim, I’m fed up with the hypocrisy’: Great counterblast on double standards from Mehdi Hassan.

Beyond satire. Instant infamy for the Fox News interviewee on the state of Islam in Britain, who in turn spawned a hilarious online riff of ‘Fox News Facts’.

January 18, 2015

Davos: new briefing on global wealth, inequality and an update of that 85 richest = 3.5 billion poorest killer fact

This is Davos week, and over on the Oxfam Research team’s excellent new Mind the Gap blog, Deborah Hardoon has an update on the mind-boggling maths of global inequality .

Wealth data from Credit Suisse, finds that the 99% have been getting less and less of the economic pie over the past few years as the 1% get more. By next year, if the 2010-2014 trend for the growing concentration of global wealth is to continue, the richest 1% of people in the world will have more wealth than the rest of the world put together.

Measurements of wealth capture financial assets (including money in the bank) as well as non financial assets such as property. It is not just inefficient to concentrate more and more wealth in the hands of a few, but also unjust. Just think of all the empty properties bought by wealthy people as investments rather than providing housing for those in need of a home. Think of the billionaire chugging out carbon emissions flying around in a private jet, whilst the poorest countries suffer most from the impacts of climate change and the poorest individuals living want for a decent bicycle to get to school or work.

Measurements of wealth capture financial assets (including money in the bank) as well as non financial assets such as property. It is not just inefficient to concentrate more and more wealth in the hands of a few, but also unjust. Just think of all the empty properties bought by wealthy people as investments rather than providing housing for those in need of a home. Think of the billionaire chugging out carbon emissions flying around in a private jet, whilst the poorest countries suffer most from the impacts of climate change and the poorest individuals living want for a decent bicycle to get to school or work.

Wealth inequality is now so extreme, that in 2014 just 80 people have the same wealth as the bottom half of the planet. The richest 80 people in the world have a collective wealth of $1,898,600,000,000, (that’s 1.9 trillion dollars) or an average of $24,000,000,000 (24 billion dollars) each. These are big numbers, lots of 0’s, so let’s try to break it down.

Wealth inequality is now so extreme, that in 2014 just 80 people have the same wealth as the bottom half of the planet. The richest 80 people in the world have a collective wealth of $1,898,600,000,000, (that’s 1.9 trillion dollars) or an average of $24,000,000,000 (24 billion dollars) each. These are big numbers, lots of 0’s, so let’s try to break it down.

Let’s get rid of all the zeroes. Wealth of $24 per person would be pretty negligible, not much you can do to invest this or purchase productive assets. Increasing this by $3 in one year wouldn’t make much difference at all, especially as prices in the economy increase.

Wealth of $24,000 could be transformative. It could enable you have own a mode of transport or farming equipment to enable your work and livelihood. It could provide cash in the bank, just in case you need some reserves if the income that you rely on is affected or you face a financial surprise or shock. $3,000 more in a year could make an important difference for you and your family.

Wealth of $24,000,000 would be more than enough for a (financially) worry free life. So long as you do not have a dangerous shopping habit, you potentially be financially secure for your entire life with this kind of wealth, owning property so that you would never need to pay rent and earning enough interest to provide a stable income, a 1% interest on this would give you an annual income of $230,000). Another $3,000,000 every year is, quite frankly, unnecessary.

Wealth of $24,000,000,000 blows my mind. Based on even tiny levels of interest, this wealth would grow faster than you could spend it. And it grows fast, an extra $3,000,000,000 in one year alone. Aside from what this extreme level of wealth might do to shopping habits and holiday destinations, what does it mean for the rest of us that do not have this amount of wealth at our disposal?

“Wealth: Having it all and wanting more” is a short research brief published today that looks at wealth data and finds that it is more unequally distributed than ever before. In 2010 it took 388 billionaires to have the same amount of wealth of the bottom half of the world, it now takes just 80 of them. The extreme wealth at the top of the distribution as desired above is not only mindblowing, but quite obscene when compared with how wealth is distributed to the rest of us in the world. The average wealth of adults in the bottom half of the world is $784, in Malawi the wealth per adult is just $230.

Why do I use the word obscene? Why is this disparity a problem? Many reasons, better articulated in Oxfam’s recent Even It Up report and by others here, here and here. But I’ll just mention one that I feel strongly about, the vicious and pernicious cycle of wealth, power and influence that leaves the rest of us excluded from determining the policies that affect us all, as stated last year in Oxfam’s “Working for the Few”.

Why do I use the word obscene? Why is this disparity a problem? Many reasons, better articulated in Oxfam’s recent Even It Up report and by others here, here and here. But I’ll just mention one that I feel strongly about, the vicious and pernicious cycle of wealth, power and influence that leaves the rest of us excluded from determining the policies that affect us all, as stated last year in Oxfam’s “Working for the Few”.

In the report, I delve into the Forbes billionaires data to identify the origins of their extreme wealth (the excel file I used is also online, so you can have a look too). Around one third inherited some or all of their wealth. But most interesting were the sectors from which their fortunes were derived. 20% of the billionaires on the 2014 list were listed as having interests or activities in the finance or insurance sector. No doubt these individuals have been hardworking, smart and creative, but we also know that companies from the finance and insurance sector spend a lot of time and money on influencing, in 2013 more than $500mil was spent on lobbying by this sector in Washington and Brussels alone. And this is just scratching the surface of how high net worth individuals and companies can use their position to influence others to support their agenda to the detriment of the rest of society, particularly the poor. There is a real cost involved here, when the policies and people that are influenced no longer work in the interests of the majority, of those most in need of support, those people that can’t afford to take their political representatives out for swanky meals. Companies from the pharmaceutical and healthcare sector are spending similar amounts on lobbying, protecting their corporate interests when the world is badly in need of the provision of affordable drugs and new vaccines – both which challenge the bottom line of pharma companies.

For a fairer and more just policy making and governance, alongside keeping lobbyists and other influencing mechanisms in check, we also need to be pro active in strengthening the voice and participation of the 99%. Transparency and open government initiatives in many countries presents an opportunity for citizens to engage, but we need to find a way to do that effectively. Strengthening unions, actively supporting causes we feel strongly about, standing up against restrictions on freedom of expression. We need more power and we need it now to prevent the runaway wealth of the rich running us into insignificance.

Lots of coverage of Deborah’s briefing in the Financial Times, BBC and Guardian, among others – top job. (And if you’re pining for this week’s Links I Liked, it’ll be along tomorrow)

January 15, 2015

Every key stat you could possibly want about humanitarianism, emergencies etc – please steal

Clearly you can’t use the term ‘killer facts’ when they concern actual deaths, so Oxfam has tweaked the name to Humanitarian Key Facts in a new  compilation (to be updated on a regular basis). It’s a powerful collection that should provide lots of link-tastic, well referenced ammunition (sorry - language problem again) for advocacy. The most striking one for me was that of the total $3trn in aid over the last 20 years, just $70bn has gone on responding to ‘natural disasters’, and only $13.4bn (0.4%) on preparing for them in advance (Disaster Risk Reduction). I thought it was a much higher proportion. Here’s a sample, co-authored with Laura Searle of the Humanitarian policy team.

compilation (to be updated on a regular basis). It’s a powerful collection that should provide lots of link-tastic, well referenced ammunition (sorry - language problem again) for advocacy. The most striking one for me was that of the total $3trn in aid over the last 20 years, just $70bn has gone on responding to ‘natural disasters’, and only $13.4bn (0.4%) on preparing for them in advance (Disaster Risk Reduction). I thought it was a much higher proportion. Here’s a sample, co-authored with Laura Searle of the Humanitarian policy team.

CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE

• In the 12 months to June 2015, the world will spend £7bn on peacekeeping (Source: UN). This is less than half of 1 percent of world military expenditure (estimated at $1.75 trillion). (Source: SIPRI)

• The five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the UK, US, France, China and Russia) account for 75 percent of the world’s arms transfers, 59 percent of global military expenditure and less than 4 percent of UN peacekeepers.

• Every year since 2008, the world has become less peaceful. In 2014, the ongoing conflicts in Syria, Ukraine and South Sudan all contributed to this continuing trend. (Source: Institute for Economics and Peace)

• By the end of 2013, 51 million people were forcibly displaced as a result of persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations. This is the highest number since the Second World War. (Source: UNHCR)

• More than 1.5 billion people already live in countries that are blighted by conflict and face repeated cycles of violence. (Source: World Bank)

• One-third of the world’s poor live in fragile and conflict-ridden countries. By 2018, this share is likely to grow to one-half, and by 2030 it could be as much as two-thirds. (Source: OECD DAC and Brookings Institution)

• There are 21 countries where the lives of women are blighted by rape and other forms of sexual violence which may be used as a weapon of war. In the space of one year (2006–2007) four women were raped every five minutes in the Democratic Republic of Congo; or more than 400,000 women in 12 months. (Source: UN and The Telegraph)

• It is notoriously difficult to count the number of people killed in conflicts, but millions of people have lost their lives in recent years. Since 1998, violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo has led to 5.4 million deaths. (Source: International Rescue Committee)

DISASTERS FROM NATURAL HAZARDS

• In the last 20 years, disasters from natural hazards have killed 1.3 million, affected 4.4 billion people, and caused almost $2tn in economic losses. (Source: Oxfam)

• The number of weather-related disasters reported has tripled in 30 years. (Source: Oxfam)

• The number of weather-related disasters reported has tripled in 30 years. (Source: Oxfam)

• An estimated 258,000 people died in Somalia from famine and food insecurity between October 2010 and April 2012. (Source: FAO)

• By the 2030s, large parts of Southern Africa and South and East Asia will be more exposed to droughts, floods and other hazards; 325 million people in extreme poverty will live in the most exposed areas. (Source: ODI)

• Small, local disasters often go unnoticed by donors and media alike. But they account for a large proportion of disasters’ global impact: 54 percent of houses damaged, and 83 percent of people injured. (Source: Oxfam)

• Disasters from natural hazards hit poor countries far harder than richer ones: 81 percent of disaster deaths are in low-income and lower-middle income countries, even though they account for only 33 percent of disasters; in 2010, the earthquake that struck Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas , killed 200 times as many people as an earthquake in Chile weeks later; Chile’s earthquake was 500 times stronger;

• Vulnerability to disasters is enormously unequal: Less than 10 percent of workers in least developed countries are covered by social security; in most industrial nations, it is almost 100 percent; 97 percent of people living on less than $4 per day have no insurance cover, and so are highly vulnerable to major risks or financial shocks.

• Disasters kill more women than men, particularly in major calamities. Women accounted for 70–80 percent of those killed by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, and according to UNDP, women and children are 14 times more likely than men to die during a disaster. (Source: LSE and UNDP)

HUMANITARIAN ACTION

• In the last decade, the number of people who need humanitarian aid and the cost of helping them has significantly increased. Funding requirements have more than doubled, to over $10bn per year. (Source: UNOCHA) For 2015, the UN has appealed for more than $16bn. (Source: UNOCHA)

• In the last decade, international funding has consistently failed to meet one third of the humanitarian need outlined in UN appeals. (Source: Development Initiatives) At $4.7bn, 2013 saw the largest shortfall since 2000 between the amount requested and the amount given. (Source: UN OCHA and Oxfam)

• Hardly any crisis gets the funds to fully meet its needs. But the amount given is extraordinarily unequal: for every $1 spent on a person affected by Haiti’s earthquake in 2010, 13 cents was spent on a person in need in South Sudan in 2013, 9 cents in Sudan, 4 cents in the Central African Republic. (Source: Oxfam – see footnotes 1 to 4)

• The world spends nearly three times as much on ice cream as it does on humanitarian aid: $59bn on ice cream against, in 2013, $22bn on humanitarian aid. (Source: Market Research and The Guardian)

• For all the talk of building local partnerships, less than 5 percent of humanitarian aid is spent directly through local groups. After Haiti’s earthquake in 2010, less than 1 percent of the total international aid went through Haitian NGOs or companies, and less than 1 percent of the international humanitarian aid was channelled through the Haitian government. (Source: Lessons from Haiti)

• In 2012, OECD countries spent just 6 percent ($630m) of their humanitarian assistance to fund Disaster Risk Reduction. (Source: Development Initiatives) Since 1991 the international community has spent $69.9bn in response to disasters, and only $13.5bn on risk reduction. (Source: ODI)

• Yet prevention is value for money: every $1 spent on disaster resilience in Kenya has saved $2.90 in reduced humanitarian spend, reduced losses and development gains. (Source: DFID)

January 14, 2015

Civil Society and the dangers of Monoculture: smart new primer from Mike Edwards

Mike Edwards has just written a 3rd edition of his book ‘Civil Society’. It’s a 130 page primer, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy reading. I found some of the  conceptual stuff on different understandings of civil society pretty hard going, but was repaid with some really interesting and innovative systems thinking, leading to what I think are some novel suggestions for how NGOs and donors should/shouldn’t try to support civil society in developing countries.

conceptual stuff on different understandings of civil society pretty hard going, but was repaid with some really interesting and innovative systems thinking, leading to what I think are some novel suggestions for how NGOs and donors should/shouldn’t try to support civil society in developing countries.

Edwards sets out some fairly arcane (to me anyway) debates, identifying three schools of thought that see CS as

‘Associational life’ that builds trust and social capital (de Toqueville, Robert Puttnam etc)

The Good Society: a good thing in itself

A protagonist in the public sphere, incubating debates that will eventually turn into laws and policies (think tobacco campaigners, or women’s rights)

‘“What to do” depends on what one understands civil society to be. Devotees of associational life will focus on filling in the gaps and disconnections in the civil society ecosystem, promoting volunteering and voluntary action, securing an “enabling environment” that privileges NGOs and other civic organizations through tax breaks, and protecting them from undue interference through laws and regulations that guarantee freedom of association.

Believers in the good society will focus on building positive interactions between institutions in government, the market and the voluntary sector around common goals such as poverty reduction, human rights and deep democracy.

Supporters of civil society as the public sphere will focus on promoting access to, and independence for, the structures of communication, extending the paths and meeting grounds that facilitate public deliberation and building the capacities that citizens require to engage with each other across their private boundaries.’

Unsurprisingly, Edwards advocates a synthesis of all three, but then he gets interesting.

‘If, like me, you see virtue in all these approaches, then the logical thing to do is to look for interventions that can strengthen the interactions between different models in order to generate an inclusive associational ecosystem matched by a strong and democratic state, in which a multiplicity of independent public spheres enable equal participation in setting the rules of the game.’

But what he sees instead is institutional monoculture – aid donors and NGOs promoting a single subsection of CS – the bits that look like Western NGOs – with disastrous consequences for the resilience and effectiveness of the system as a whole:

But what he sees instead is institutional monoculture – aid donors and NGOs promoting a single subsection of CS – the bits that look like Western NGOs – with disastrous consequences for the resilience and effectiveness of the system as a whole:

‘the approach of the civil society-building industry that has proliferated since 1989 – with some exceptions – resembles a crude attempt to manipulate associational life in line with Western, and specifically North American, liberal-democratic norms: pre-selecting organizations that donors think are most important (advocacy NGOs or other vehicles for elites, for example, usually based in capital cities), ignoring domestic expressions of citizen action that do not conform to Western expectations (such as informal, village- or clan-based associations in Africa and the Islamic world, more radical social movements or pre-political formations), spreading mistrust and rivalry as fledgling groups compete for foreign aid, and creating a backlash when associations are identified with foreign interests.

The creation of public spheres is usually ignored, apart from occasional support to independent media groups and organizations promoting government accountability. And ignoring Ralf Dahrendorf’s warning that “it takes six months to create new political institutions, six years to create a half-way viable economy, and . . . sixty years to create a civil society,” project timescales are collapsed to bite-sized two- or three-year chunks and accountability is reoriented up the system to outside donors and regulators.

Nurturing civic institutions takes careful and sensitive accompaniment over long periods of time. By contrast, the aid industry resembles a bulldozer driven by someone convinced that they are heading in the right direction, but following a map made for another country at another time. The Coalition Provisional Authority’s insistence that Iraq needed a Ministry of Civil Society in the chaos that emerged after the US occupation is a good example of priorities gone horribly awry.’

And he has some very interesting suggestions for how to put it right:

‘The first rule of thumb is always to look for forms of associational life that “live” relatively independently in their context – not just the “usual suspects.”

Healthy ecosystem. With shark.

They may be conservative-minded mosque associations in Lebanon (which are contributing to the development of tolerance), burial societies in South African townships (which played key social, economic and political roles under apartheid) or labor unions in France and Brazil (which have been prime movers in the burgeoning global justice movement). It is groups like these that occupy the frontiers in organizing new responses to problems of community and association against the background of globalizing capitalism, resurgent nationalism, and the fragmentation they breed.

Second, we should focus on the associational ecosystem by fostering the conditions in which all of its components can function more effectively, alone and together. If the “soil” and the “climate” are right, associational life will grow and evolve in ways that suit the local environment. This requires support to as broad a range of groups as possible, helping them to work synergistically to defend and advance their visions of civic life, providing additional resources for them to find their own ways of marrying flexible, humane service with independent critique, and leaving them to sort out their relationships both with each other and with the publics who must support them, and to whom they must be accountable, if their work is to be sustained.

Third, we should focus as much attention as possible on strengthening the financial independence of voluntary associations, since dependence on government contracts, foundations or foreign aid is the Achilles’ heel of authentic civic action.’

So the litmus test for a good civil society strategy should include questions like

What are we doing on the enabling environment to that any civil society group, (even ones we don’t like) can flourish?

Do we support a range of partners who don’t look like us, and don’t know or even like each other?

Have we helped our partners to learn how to raise funds locally so that they can wean themselves off aid?

Really interesting stuff

January 13, 2015

Is this the best paper yet on Doing Development Differently/Thinking and Working Politically?

Some of the old lags have reacted to all the hype around TWP/DDD with ‘any aid worker worth their salt knows that all ready – what’s new’?’

An outstanding new paper from Jaime Faustino and David Booth takes up that challenge in one particular context – advocating reforms in the Philippines – that has much wider implications. Jaime works for The Asia Foundation in the Philippines, and has become something of a TWP celebrity. At the ODI, David has been an influential voice in rethinking governance work. Their paper is crisply written, full of concrete suggestions, and thoroughly engrossing.

Their focus is ‘development entrepreneurs’ (DEs) – not grandstanding politicians, or Tahrir Square type revolutionaries, but the usually-invisible reformers working within the system, in this case to introduce substantial reforms in education, taxation, civil aviation regulation or property rights (I’ve covered some of these stories in a previous post). The paper is aimed at the big bilateral agencies, but has clear implications for NGOs too.

Here’s how the authors summarize the role of DEs

‘Their focus is on identifying objectives that are technically sound and politically possible. Technical soundness is assessed in terms of:

1. Impact: The likelihood the measure will change the incentives and behavior of people and organizations sufficiently, so development outcomes improve;

2. Scale: The prospects the reform will spread well beyond the initial project site; and

3. Sustainability: The likelihood the reform will continue without additional donor support.

Experience in the Philippines suggests, in addition, there is particular value in aiming for reforms that are ‘self-implementing’ in the sense that they lock in new market dynamics or patterns of behavior. This is most likely to be achieved by measures that alter the incentives of politicians, officials, firms and/or citizens without requiring them to redefine their interests or values in a fundamental way. In addition, the selected objective needs to be politically possible, meaning there is a reasonable prospect of the change being introduced, given the prevailing political realities.

Experience in the Philippines suggests, in addition, there is particular value in aiming for reforms that are ‘self-implementing’ in the sense that they lock in new market dynamics or patterns of behavior. This is most likely to be achieved by measures that alter the incentives of politicians, officials, firms and/or citizens without requiring them to redefine their interests or values in a fundamental way. In addition, the selected objective needs to be politically possible, meaning there is a reasonable prospect of the change being introduced, given the prevailing political realities.

The second distinctive feature of the model is the use of an entrepreneurial logic that encourages iterative ‘learning by doing’. Navigating through complex development challenges to discover possible pathways to reform must involve a great deal of trial and error.

Entrepreneurial logic involves making a series of small bets instead of seeking large all-or-nothing opportunities. Decisions at each stage depend on educated guesses, drawing on an equal combination of science, the results gained with small bets and imagination. This involves embracing error as a vital source of learning and the willingness and ability to adjust to new information in a dynamic environment.

Part of the attraction of the DE concept is that it builds on a lot of research and experience in the private sector. Jaime and David summarize ‘five principles of entrepreneurship’, each of which raises important challenges for NGOs (summarized in the square brackets):

1. Bird in Hand: An acceptance of how the world is, what resources are at their disposal and whom they know. [NGO angle: tension with normative/transformational agenda – too much acceptance of status quo here?]

2. Affordable Loss: Recognition that failures and setbacks are part of the process of finding and determining the ‘winning formula’. Instead of making large bets at the start, entrepreneurs make a series of small bets. Based on feedback and assessment, further actions are taken. [NGO angle: who absorbs losses – partners, NGOs or their funders?]

3. Strategic Partnerships: Understanding that collaboration, working with others, is essential for success. Entrepreneurs build partnerships with self-selecting stakeholders. By obtaining these commitments from key partners early on, entrepreneurs reduce uncertainty and co-create with interested partners. [NGO angle: that doesn’t sound very inclusive – what about voices that are not already at the table? And what are implications for attribution and proving impact?]

4. Leveraging Contingencies: Awareness that new developments and surprises can be turned into opportunity. For entrepreneurs, the correct response to surprises is ‘adjust and embrace the change’. [NGO angle: a big challenge – see you can’t take a supertanker white-water rafting]

5. Pilot in the Plane: Entrepreneurs tend to focus on activities within their control. ‘An entrepreneurial worldview is based in the belief that the future is neither found nor predicted, but rather made.’ [NGO angle: when you’re small, fewer things are within your control – the danger is that seeking to be in charge reduces your ambition by making you focus on easily measurable impacts, rather than ‘riding the wave’]

The key to this way of working is failing and learning faster – can NGOs do speed?

DEs are leaders, but of a different sort from the national Big Men (Kagame, Meles) who I’ve previously criticised David for being too keen on. Above all,  they work in small teams (the paper quotes Amazon’s Jeff Bezos: If it takes more than two pizzas to feed the team, it is too big). They add some fascinating suggestions (see box) for the kind of skills that a team needs to bring together.

they work in small teams (the paper quotes Amazon’s Jeff Bezos: If it takes more than two pizzas to feed the team, it is too big). They add some fascinating suggestions (see box) for the kind of skills that a team needs to bring together.

What can external supporters (aid agencies, INGOs etc) do to help/not hinder Development Entrepreneurs? The paper recommends backing ‘intermediary organizations’ with the skills to spot and support DEs (which probably means cloning Jaime), and spending more via flexible grant agreements. ‘As one development entrepreneur put it to us, ‘We are going to do this anyway, so giving us resources is a bonus and makes it a little easier.’’ I suspect that was Jaime too. Maybe the next paper should be entitled ‘where there is no Faustino’……

And my favourite quote of the paper (and 2015 thus far): ‘Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth’ – from Mike Tyson (and he should know).

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers