Duncan Green's Blog, page 171

February 9, 2015

What are the implications of ‘doing development differently’ for NGO Campaigns and Advocacy?

I’ve been having fun recently taking some of the ideas around ‘Doing Development Differently’ and applying them to INGOs, building on the post I wrote last year on ‘You can’t take a supertanker white-water rafting’. The Exam Question is: Given complexity, systems thinking and the failure of top down approaches, what future, if any, is there for International NGOs? Paper and blog forthcoming – bet you can’t wait.

I’ve been having fun recently taking some of the ideas around ‘Doing Development Differently’ and applying them to INGOs, building on the post I wrote last year on ‘You can’t take a supertanker white-water rafting’. The Exam Question is: Given complexity, systems thinking and the failure of top down approaches, what future, if any, is there for International NGOs? Paper and blog forthcoming – bet you can’t wait.

Last week, I discussed the draft paper with my campaigns, policy and influencing colleagues (we seem to have stopped saying ‘advocacy’ – not quite sure why). I kicked off by suggesting some implications/questions for them:

1. For INGOs, learning to go white water rafting means big shifts, which could include

Consciously pursuing many more experiments, built on fast feedback, learning how to identify failure and success much faster, then iterating and adapting into new experiments. How does that differ from standard campaign approaches?

In NGO world, rafts are are small organizations, more likely than supertankers to develop innovative ideas, and respond quickly to shifting contexts. But a large NGO can support them and scale up new approaches. So the best combination might be to make more effort to identify and steal good ideas, and to spin off successful experiments as soon as possible, so that they can flourish away from the clutches of corporate process.

2. Why don’t we do more on spotting and backing existing winners (positive deviance) rather than trying to come up with our own solutions to every problem?

3. In complex systems, where organizations and ideas are constantly rising and falling, the best unit of analysis may not be the project, but the individual. Why don’t NGOs do more to support people not projects (scholarships, more investment in leadership)?

The conversation threw up some really interesting additional observations and suggestions:

What do we mean by ‘Power’? We all pay lip service to the importance of understanding the nature and distribution of power in the systems we seek to influence, but often, we mean different things by the phrase ‘power analysis’. Campaigners and advocates think much more in terms of challenging power, whereas a lot of programme people (especially in governance, but also livelihoods work on things like producer organizations), focus more on personal and collective empowerment. In terms of Jo Rowlands’ ‘3 (or 4) powers’ model, we have a bit of a Venn Diagram going on here. Campaigners think in terms of Power With and Power To, whereas programmes work on Power Within and Power With. No wonder we’re confused.

What do we mean by ‘Power’? We all pay lip service to the importance of understanding the nature and distribution of power in the systems we seek to influence, but often, we mean different things by the phrase ‘power analysis’. Campaigners and advocates think much more in terms of challenging power, whereas a lot of programme people (especially in governance, but also livelihoods work on things like producer organizations), focus more on personal and collective empowerment. In terms of Jo Rowlands’ ‘3 (or 4) powers’ model, we have a bit of a Venn Diagram going on here. Campaigners think in terms of Power With and Power To, whereas programmes work on Power Within and Power With. No wonder we’re confused.

Critical Junctures: Events play a huge role in many big changes, whether of policy, politics, or broader attitudes and beliefs. Within NGOs the people who are geared to respond to events are the emergencies people – long term development and campaigns teams are often less able to respond. What could influencers learn from their humanitarian colleagues about reacting better to big events like the Egyptian Revolution, a new and more progressive government, or a financial or climate meltdown? For example, what could be put in place before the more predictable events (floods, elections), to enable us to react more rapidly afterwards (e.g. 90% cooked policy papers, coalitions ready to go public in the days after a major shock) while there is still an appetite for new ideas and approaches? Or have a system like the humanitarians to move resources and people around in response to events?

Detector networks: influencers are sometimes too caught up in their own ideas and networks to spot when things have changed in the world outside, even when those changes bring new opportunities. The first we researchers in Oxford new of the global price spike in 2008 was when journalists phoned up and asked for a comment. Field staff on the ground may be better placed to spot relevant trends in their own context, even if they don’t add those up to see global trends, as may journalists or other observers. How do we develop better ‘early warning systems’ to harvest such signals? A monthly ring round of 1000 key informants? A big data scraping exercise to spot words appearing more frequently on twitter or in our email subject headings (partnership with GCHQ anyone? – only joking)?

Global, National or City? Like lots of other INGOs, Oxfam is shifting resources from global influencing to national level. But that can be challenged on two grounds: firstly, there is still a huge gap in global governance, with few active players – INGOs may be better placed to influence there than in the crowded cauldron of national politics. But at the other end of the spectrum, many of the most interesting innovations at national level emerge through experiments by city administrations, and are then adopted at national level (think cash transfers, participatory budgeting or low carbon transitions). So is it worth consciously pursuing city influencing strategies, identifying the more promising urban authorities, and then developing the right staff, partners, networks, research, tactics etc?

Finding Funding: to some extent, all of this stands or falls on our ability to find funders willing to support this kind of innovation. I’m actually optimistic, because so many of the interesting things I see in Oxfam in part owe their inspiration to examples of ‘Good Donorship ’. But we may need to develop new kinds of funding instrument (eg innovation/influencing funds that allow us to break up larger chunks of cash into smaller, better targeted pieces that can be disbursed quickly and won’t overwhelm the recipient).

Any more suggestions?

February 8, 2015

Links I Liked

Never make predictions, especially about the future: 42 predictions by futurologists from c1960 (some correct – driverless cars) [h/t Tim Harford]

Flurry of posts on life and love in the aid biz:

How not to get a job in development. Some painful examples of pressing the self destruct button

‘Your mother will love the fact that you’re dating someone so caring’ 52 reasons to date an aid worker.

What does it take to start a development career? Check out DevQuest, a site for newcomers to the sector

Fascinating summary of research on links between aid & conflict: small aid (eg cash transfers) reduces it; big aid (eg infrastructure) seems to increase it.

Is it exciting or depressing that the OECD has persuaded mining giants to commit not to sanction torture, human rights abuses etc?

Tide turns on water privatization? 180 cities in 35 countries have re-municipalised” water systems in past decade.

The mother of all counterfactuals. Has the ICC had a deterrent effect on human rights abusers? (Answer: a cautious yes)

Must read from Owen Barder: Why 21st C development policy must go (way) beyond aid (UK MPs agree)

This is brilliant @Eboladeeply & @okayafrica produce on-the-ground Ebola reporting from Sierra Leone. Here’s the first 2 minute episode: [h/t David Sasaki]

February 5, 2015

What should Europe do about Illicit Financial Flows? Five take-aways from the African Union’s High-Level report

This post by tax campaigner Christian Hallum (@ChrHallum) also appeared on the Eurodad blog.

Last Saturday a landmark decision was taken when the African Union, made up of 54 African Heads of State, adopted the report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows (IFF). This report documents the scale and impact of IFF from the continent and gives a range of policy recommendations. Our friends at the Tax Justice Network says the report is “probably the most important report yet produced on this issue” and for good reasons.

The new report is not only a strong testament to the importance that African leaders are placing on the issue of IFF, but its publication ahead of July’s Financing for Development (FfD) conference is an indication that the issue is likely to figure prominently among items raised by developing countries during the negotiations.

While the report has its regional focus on Africa the implications of its findings and recommendations are intrinsically linked to the European continent. Here, we identify the top five take away points for Europe:

1. Tax dodging by transnational companies is the main driver of illicit financial flows in Africa…

The report clearly identifies transnational corporations as “by far the biggest culprits of illicit outflows” (p3). By massaging their accounts and structuring their operations in tax havens, transnationals illicitly draw money out of the African continent, with no tax paid on these funds.

The report clearly identifies transnational corporations as “by far the biggest culprits of illicit outflows” (p3). By massaging their accounts and structuring their operations in tax havens, transnationals illicitly draw money out of the African continent, with no tax paid on these funds.

The report highlights many examples of the tricks used by companies, including how transnational companies in Mozambique under-declare the value of the shrimps they export; how 100,000 barrels of oils goes missing each day in Nigeria; or how an investor in South Africa set up subsidiaries with a handful of staff in Switzerland and in the UK to avoid paying $2 billion in taxes (p27-28).

The report tackles corruption and money laundering, but it also makes it clear that we cannot tackle IFF without tackling the issue of tax dodging transnational companies. European officials and governments who want to believe that IFFs are only about corruption and that all transnational corporations are beneficial to developing countries should listen and learn.

2. …And European countries are a centre for these flows

The report notes that “illicit financial outflows whose source is Africa end up somewhere in the rest of the world.” (p4). One of the innovations of the Panel’s report is that they are able to narrow down where some of the illicit flows end up, and it turns out that a lot of it comes to Europe. For example, 22.5% of the illicit flows emanating from Nigeria’s oil sector end up in Spain, while 11.7% of IFF from Algerian oil ends up in Italy and 23.6% of IFF from Cote d’Ivore’s cocoa sector ends up in Germany (p100). At the same time, the report notes that the proceeds from corruption have a tendency to end up in bank accounts in developed countries (p46).

“Countries that are destinations for these outflows also have a role in preventing them and in helping Africa to repatriate illicit funds and prosecute perpetrators” notes the report.

There are three obvious solutions which European leaders can introduce. Automatic exchange of information for tax purposes, public country by country reporting and  public registries of beneficial owners of companies, trust and similar legal structures. However, while the European and G20 governments have taken steps to implement these tools in ways that create more transparency for themselves, there are not yet any solid transparency initiatives which will create transparency from an African perspective.

public registries of beneficial owners of companies, trust and similar legal structures. However, while the European and G20 governments have taken steps to implement these tools in ways that create more transparency for themselves, there are not yet any solid transparency initiatives which will create transparency from an African perspective.

3. Capacity building will not solve the problem…

The report states that capacity building of tax administrations in Africa would be a good idea, and that African countries would need an additional 650,000 new tax officials to have the same ratio of tax officials to their population as OECD countries (p59). This is an area supported by several European aid agencies.

However, the report does state the limits of this approach: “It is somewhat contradictory for developed countries to continue to provide technical assistance and development aid (though at lower levels) to Africa while at the same time maintaining tax rules that enable the bleeding of the continent’s resources through illicit financial outflows” (p60).

As long as the international financial system is rigged against Africa more tax inspectors alone will not fix the situation. The report notes that “the critical ingredient in the struggle to end illicit financial flows is the political will of governments, not only technical capacity” (p.3).

4. …Instead the solution is political with massive implications for European leaders

The report gives many recommendations for African leaders, but for our purpose it is interesting to note that many of the recommendations speak directly to developed countries. There are at least five recommendations that should be on the radar for European decision makers.

• Firstly, the report calls for fully public registers of beneficial owners of companies and trusts (p86). The EU had a chance to deliver this when a deal was reached on the revision of the EU’s Anti-Money Laundering Directive in December 2014. While government’s failed to agree that registries should be public, it is still perfectly possible for individual member states to decide this, and France, the UK (on companies only), and Denmark have already announced plans to make their registers public. Unless the registries are public, the developing country governments and citizens will have great difficulties accessing the information, and other member states therefore need to follow suit and make their registries public.

• Secondly, the report calls for comprehensive and publicly available Country by Country reporting (p85). The EU has adopted such standards for its banking industry through the Capital Requirements Directive, but it is yet to take the logical step to extend it to all sectors.

• Secondly, the report calls for comprehensive and publicly available Country by Country reporting (p85). The EU has adopted such standards for its banking industry through the Capital Requirements Directive, but it is yet to take the logical step to extend it to all sectors.

• Thirdly, there is a strong focus on the need for more balanced Tax Treaties between developed and developing countries, noting that “we are particularly concerned about the risk that African countries face in making unbalanced concessions with regards to double taxation agreements” (p58-59). Research conducted by Eurodad supports this concern, showing that European tax treaties with developing countries significantly reduce withholding tax rates and allow for abusive treaty shopping. Such treaties obviously need to be renegotiated or removed all together.

• Fourth, in relation the EU system of Automatic Exchange of Information for tax purposes through the Directive on Administrative Cooperation (DAC) it is significant that the report calls for “common but differentiated responsibilities” for developing countries (p46). This would entail allowing developing countries a transitional period toward reciprocal Automatic Exchange of Information, during which they receive information automatically even though they are not able to send any information back.

• Lastly, the report notes that developed countries could “undertake an analysis of the impact of the tax systems of developed countries on African countries” (p60). Such spill-over analysis has already been conducted by some European countries, including the Netherlands and Switzerland. It would no doubt be useful for these exercises to be extended to all European countries as well as the EU as a whole. It is also vital that these studies are followed up with political action to remove the negative impacts on developing countries.

In short, Europe plays a key role in the illicit flow of financial resources from Africa, and we must also play a key role in solving the problem.

5. African leaders will not be sidelined anymore in international negotiations

So why have the changes that are necessary for Africa’s development not happened before? While the report does not try to answer this question directly it does provide some explanation when it states “although the OECD is working to address issues of base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS), this work is not principally geared to developing country concerns.” (p66). The solutions so far proposed by the BEPS initiative do not follow the recommendations contained in the report. For example, BEPS does not call for Country by Country reporting to made publicly available, and does not include provisions for Automatic Exchange of Information with developing countries following the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”. But then again the developing countries are not represented in the OECD. As a result, the report recommends that “Africa needs to act in concert with its partners to ensure that the United Nations plays a more coherent and visible role in tackling IFFs”. This demand links closely to the ongoing negotiations on financing for development, where African governments, together with a broad group of other developing countries, have demanded an intergovernmental UN body on tax matters, to allow them a seat at the table when decisions on international tax reform are taken. European governments must support this call and engage in global cooperation between developed and developing countries to close the bleeding wound, which illicit financial flows constitute for our economies.

February 4, 2015

Are developing countries heading for another debt crisis? And if so, what is anyone doing about it?

Skating on thin ice is an occupational hazard in my job, but it was really cracking underfoot at a recent Chatham House Rules roundtable on ‘debt crisis prevention in

No, not that debt crisis

developing countries’. The only way to survive is to stay quiet, nod and look thoughtful when people refer to completely unintelligible things like ‘the clarification of pari passu, which created difficulties in the US that we’re all aware of.’ But I don’t see why a detail like not understanding what was said should stop me from blogging about it ……

The topic – are developing countries heading for another debt crisis and if so, who/when/how/what can be done? – could hardly be more topical. As we met, British Finance Minister George Osborne was meeting his unbelievably cool Greek counterpart, Yanis Varoufakis to discuss the Greek debt crisis. The Economist was running articles on looming debt crises in Africa, affecting The Gambia, Ghana, Zambia and others.

So what did I learn from the assembled debt geeks?

First, after bottoming out in the mid 2000s, levels of developing country borrowing have risen and come from an

Sovereign bond issuances in Sub-Saharan Africa. Source: Annalisa Prizzon & Judith Tyson, ODI

increasing range of sources (‘heterogeneity’ seems to be the favourite word in these circles). Bonds (both private and government issued), Public Private Partnerships (PPPs), concessional loans, market-rate loans, aid, money from new lenders like China and Brazil. In Africa sovereign bond issuances have ‘skyrocketed’, with $6bn issued just last year. 15 African countries have joined in, including several former debt relief (HIPC) recipients.

Is that a good thing or a bad thing? All depends. The costs of different kinds of ‘instrument’ (as a percentage, net of the amount of finance provided) varies hugely – see this handy comparison from a recent Development Finance International report. PPPs turn out to cost an arm and a leg, which is alarming, given the emphasis being put on them as a source for funding the post-2015 goals, while getting money for free (aid grants) is the best value, but

Off = Official; Con = Concessional; Dom = Domestic. Work the rest out for yourselves.

there are lots of gradations in between.

There were both debt optimists and pessimists in the room, but all agreed that at least 8 African ‘problem cases’ are heading for the brink, and that some in the Caribbean and Pacific are already having a debt crisis. .

And it’s not always their governments’ fault. External shocks, such as the current commodity price collapse, often sweep all before them, and it makes little difference whether the World Bank has decreed a country well governed or not.

The traditional political dividing lines were in evidence, albeit couched in very polite terms, including ‘market-based v statutory approaches’ and ‘creditor v lender responsibility’. On the latter, there were lots of warm words on shared responsibility for both preventing debt crises, and then sharing the burden should they occur. But all the real pressure seems to be on the borrower countries to reform their economies and repay their debts (as per usual), with plentiful excuses for avoiding lenders doing their share. Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism? ‘No appetite on the IMF board’ (those guys definitely show signs of an eating disorder when it comes to regulation); the UK urging other rich countries to follow its lead on banning vulture funds? ‘we need to consult with other countries first’. Endorsing UNCTAD’s Principles on Promoting Responsible Sovereign Lending and Borrowing? Um, we need to think more about that.

On a more systemic level, all that heterogeneity is creating a fragmented ‘non system’ rather than a sensible international architecture for handling debt in good times and bad. Which got me thinking about complexity and Andrew Haldane’s brilliant paper on the financial crisis. Haldane argues (delightfully) that financial regulators are like dogs trying to catch a frisbee – if they try and work it all out in advance, it’s like trying to apply Newton’s laws of motion to work out where the Frisbee lands. Hopeless. Instead, you need a few simple rules, and fast feedback (and the ability to run fast).

On a more systemic level, all that heterogeneity is creating a fragmented ‘non system’ rather than a sensible international architecture for handling debt in good times and bad. Which got me thinking about complexity and Andrew Haldane’s brilliant paper on the financial crisis. Haldane argues (delightfully) that financial regulators are like dogs trying to catch a frisbee – if they try and work it all out in advance, it’s like trying to apply Newton’s laws of motion to work out where the Frisbee lands. Hopeless. Instead, you need a few simple rules, and fast feedback (and the ability to run fast).

A lot of the people in the room still seem to be trying to apply Newton, seeking to predict the trajectory of debts in ever more fragmented and unpredictable systems. Haldane’s paper suggests two better approaches: firstly some simple ‘thou shalt not’ regulations, (in his case, separating commercial and investment banking) which are less fallible than the clever stuff, and second paying much more attention to detecting and responding rapidly (and fairly) to debt crises as they occur.

This topic is going to get louder as we approach the big Financing for Development summit in Addis in July. For some background from people who actually know what they’re talking about, check out this paper on debt sustainability, and this more general paper on FFD, both from ODI.

February 3, 2015

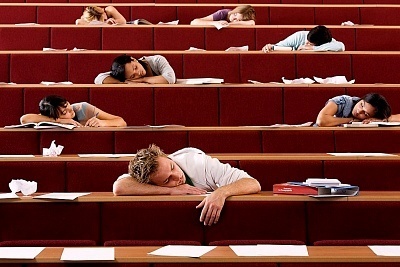

How do you keep 100 students awake on a Friday afternoon? Fast feedback and iterative adaptation seem to work

I wrote this post for the LSE’s International Development Department blog

There’s a character in a Moliere play who is surprised and delighted to learn that he has been speaking prose all his life without knowing it. I thought of him a couple of weeks into my new role as a part-time Professor in Practice in LSE’s International Development Department, when I realized I had been using ‘iterative adaptation’ to work out how best to keep 100+ Masters students awake and engaged for two hours last thing on a Friday afternoon.

The module is called ‘Research Themes in International Development’, a pretty vague topic which appears to be designed to allow lecturers to bang on about their research interests. I kicked off with a discussion on the nature and dilemmas of international NGOs, as I’m just writing a paper on that, then moved on to introduce some of the big themes of a forthcoming book on ‘How Change Happens’.

As an NGO type, I am committed to all things participatory, so ended lecture one getting the students to vote for their preferred guest speakers (no I’m not publishing the results). In order to find out how the lectures were going, I also introduced a weekly feedback form on the LSE intranet (thanks to LSE’s Lucy Pickles for sorting that out), and asked students to fill it in at the end of the session. The only incentive I could think of was to promise a satirical video (example below) if they stayed long enough to fill it in before rushing out the door – it seemed to work. The students were asked to rank presentation and content separately on a scale from ‘awful’ to ‘brilliant’, and then offer suggestions for improvements.

It’s anonymous, and not rigorous of course (self-selecting sample, disgruntled students likely to drop out in subsequent weeks etc), but it has been incredibly useful, especially the open-ended box for suggestions, which have been crammed full with useful content. The first week’s comments broadly asked for more participation, so week two included lots of breakout group discussions. The feedback then said, ‘we like the discussion, but all the unpacking after the groups where you ask what people were talking about eats up time, and anyway, we couldn’t hear half of it’, and asked for more rigour, so week three had more references to the literature, and 3 short discussion groups with minimal feedback – it felt odd, but seemed to work.

At this point, the penny dropped – I was putting into practice some of the messages of my week two lecture on how to work in complex systems, namely fast feedback loops that enable you to experiment, fail, tweak and try again in a repeat cycle until something reasonably successful emerges through trial and error. One example of failing faster – I tried out LSE’s online polling system, but found it was too slow (getting everyone to go online on their mobiles and then vote on a series of multiple choice questions) but also not as energising as getting people to vote analogue style (i.e. raising their hands). The important thing is getting weekly feedback and responding to it, rather than waiting til the end of term (by which time it will be too late).

The form is not the only feedback system of course. As any teacher knows, talking to a roomful of people inevitably involves pretty intense realtime feedback too – you feel the energy rise and fall, see people glazing over or getting interested etc. What’s interesting is being able to triangulate between what I thought was happening in the room/students’ heads, and what they subsequently said. Broad agreement, but the feedback suggested their engagement was reassuringly consistent (see bar chart on content), whereas my perceptions seem to amplify it all into big peaks and troughs – what I thought was a disastrous second half of lecture two appears to have just been a bit below par for a small number of students.

The form is not the only feedback system of course. As any teacher knows, talking to a roomful of people inevitably involves pretty intense realtime feedback too – you feel the energy rise and fall, see people glazing over or getting interested etc. What’s interesting is being able to triangulate between what I thought was happening in the room/students’ heads, and what they subsequently said. Broad agreement, but the feedback suggested their engagement was reassuringly consistent (see bar chart on content), whereas my perceptions seem to amplify it all into big peaks and troughs – what I thought was a disastrous second half of lecture two appears to have just been a bit below par for a small number of students.

The feedback also helps crystallize half-formed thoughts of your own. For example, several complained about the disruption of students leaving in the middle of the lecture, something I also had found rather unnerving. So I suggested that if people did need to leave early (it’s last thing on Friday after all), they should do so during the group discussions – much better.

What’s been striking is the look of mild alarm in the eyes of some of my LSE faculty colleagues, who warned against too much populist kowtowing to student demands. That’s certainly not how it’s felt so far. Here’s a typical comment ‘I think that this lecture on the role of the state tried to take on too much. This is an area that we have discussed extensively. I think it would have been more useful to focus on a particular aspect, perhaps failed and conflict-affected states since you argue that those are the future of aid’. Not a plea for more funny videos (though there have been a few of those), but a reminder to check for duplication with other modules, and a useful guide to improving next year’s lectures.

What is also emerging, again in a pleasingly unintended way, is a sense that we are designing this course together and the students seem to appreciate that (I refuse to use the awful word co-create. Doh.) Matt Andrews calls this process ‘Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation’ – I would love to hear from other lecturers on more ways to use fast feedback to sharpen up teaching practices.

And now of course it’s over to the students themselves to say what’s really been going on…..

February 2, 2015

The real population boom – the over 60s: great new killer facts and graphics from Age International

Ageing is one of those development issues that is only going to get bigger. A new report from Age International pulls together all the killer facts and

infographics you should need to be convinced, and lots of eminent talking heads (Margaret Chan, Richard Jolly, Mary Robinson etc) to drive home the message. Here’s a selection

Today, 868 million people are over 60

62% of people over 60 live in developing countries; by 2050, this number will have risen to 80%.

Over the last half century, life expectancy at birth has increased by almost 20 years.

340 million older people are living without any secure income. If current trends continue, this number will rise to 1.2 billion by 2050.

80% of older people in developing countries have no regular income.

80% of older people in developing countries have no regular income.Only one in four older people in low-and middle-income countries receive a pension.

Nearly two-thirds of the 44.4 million people with dementia live in low-or middle-income countries.

In countries like Zimbabwe and Namibia, up to 60% of orphaned children live in grandparent-headed households. In these situations, grandmothers are more likely to be the main carers.

And here’s a puff video for the report and Age International

February 1, 2015

Links I Liked

This week’s displacement-activity selection from the best of the twitterstream

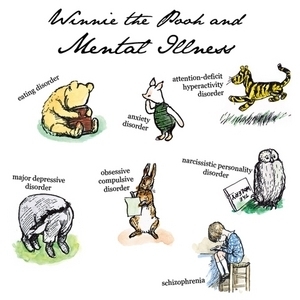

Lots of traffic about the need to destigmatize mental illness, but what really got to me was this reinterpretation of Winnie the Pooh. Is nothing sacred?

Extraordinary takedown of Winston Churchill (by Churchill) – choice quotes include “I am strongly in favour of using poison gas against uncivilised tribes” [h/t Alan Beattie]

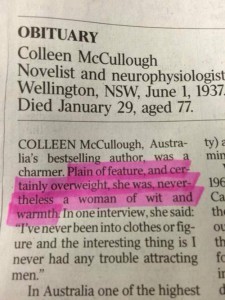

And you thought death put an end to sexism? An extraordinary obituary in The Australian of author of The Thorn Birds (highest-selling Australian book of all time ) and Yale Neuroscientist Colleen McCullough [h/t @vanbadham] More discussion on sexist obits here

And you thought death put an end to sexism? An extraordinary obituary in The Australian of author of The Thorn Birds (highest-selling Australian book of all time ) and Yale Neuroscientist Colleen McCullough [h/t @vanbadham] More discussion on sexist obits here

Ouch. 52 reasons not to date an aid worker. (No. 21: All conversations lead to a time when they were in …)

Some mixed blogger news

Very disturbing. Uberblogger Andrew Sullivan has decided to stop posting in order to read books and ‘walk around

in my own thoughts’. You won’t get rid of me that easily – all I ever think about is blogging.

On the other hand, this is going to be fun. Syriza’s new Finance Minister, the ridiculously cool Yanis Varoufakis, is going to carry on blogging regardless, providing instant feedback on the unfolding drama in Greece. There’s even a free ebook of extracts from his new book on the Eurocrisis.

And I am one happy blogger, after @studenthubs makes FP2P its top banana. Thanks. (Cue humble bragging, honoured to be in such august company, yadda yadda). Sincerely hope you are reading the others too.

Meanwhile, the fallout from Deborah Hardoon’s Davos paper on inequality rumbles delightfully on

‘Critics of Oxfam’s Poverty Statistics Are Missing the Point’. The New Yorker nails the ‘silly arguments’ over the 80 richest individuals have wealth of 3.5bn poorest stat

Inequality czar Branko Milanovic backs us and also asks why we can’t grade the megarich on the predator-wealth creator spectrum?

But funniest of the lot was watching a multimillionaire ‘celebrate’ the stat; watch the interviewer’s double take

January 29, 2015

Migrant remittances are even more amazing that we thought

At least in economic terms, migration appears to be some kind of developmental wonder-drug. Remittances from migrants to developing countries are  now running at some three times the volume of aid, and barely faltered during the 2008-9 financial crisis (see graph). The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report looks at the impact of migrant remittances on developing countries and consumption, especially during crises. Here’s their conclusions (my limited understanding of the econo-speak is that procyclical is bad – means everything goes up and down in synch, exacerbating volatility. Countercyclical is good, as things move in different directions, smoothing out overall volatility. Acyclical is somewhere in between):

now running at some three times the volume of aid, and barely faltered during the 2008-9 financial crisis (see graph). The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report looks at the impact of migrant remittances on developing countries and consumption, especially during crises. Here’s their conclusions (my limited understanding of the econo-speak is that procyclical is bad – means everything goes up and down in synch, exacerbating volatility. Countercyclical is good, as things move in different directions, smoothing out overall volatility. Acyclical is somewhere in between):

‘Remittances are relatively stable, and acyclical. In a substantial proportion of the countries, remittance receipts are not significantly related to the domestic business cycle. In contrast, debt flows and foreign direct investment are procyclical.

Stability and acyclicality imply that remittances have the potential to make a critical contribution in supporting consumption in the face of economic adversity. This is particularly important in developing countries, where remittances are used to finance household consumption directly.

Remittances have also been stable during episodes of financial volatility when capital flows fell sharply. This stabilizing effect tends to be greater for remittance-receiving countries with a more dispersed migrant population.

Remittances are associated with more stable domestic consumption growth. Countries with large remittance receipts tend to display less correlation between output and consumption growth over the business cycle. Such consumption behavior often enhances welfare.

Development’s footsoldiers?

These findings provide additional evidence of the beneficial effects of remittances. While household members may not themselves base their decisions to work abroad mainly on a desire to send stable remittances back home, these benefits provide a rationale to implement policies in recipient countries to reduce impediments to remittances, like lowering the costs of sending remittances, avoiding the taxation of remittances, and doing away with multiple exchange rate regimes. These impediments often discourage remittances as well as drive them into informal channels. Specific policy areas to be considered are as follows:

Costs of Remittances. While the average price of retail cross-border money transfers has been falling, it remains high. The average cost of sending about US $200 fell from 9.8 percent in 2008 to 7.9 percent in the third quarter of 2014. It will be important to reduce such costs further by ensuring competition in money transfer services, establishing an appropriate regulatory regime for electronic transfers, and supporting improvements in retail payments services.

Taxes on Remittances. Governments may be tempted to tax remittances in an effort to increase revenue. In general, this would discourage remittances and is likely to have a direct negative effect on household welfare. From the viewpoint of tax equity, one might note in addition that these transfers are made from after-tax income earned in source countries.

Exchange Rate Regime. Exchange rate flexibility provides an automatic stabilizer to recipients of remittances, in that the domestic currency value of remittances increases when the U.S.-dollar value of the currency drops, as it usually does during an adverse event. Dual exchange rate systems, in contrast, may deter remittance inflows, by artificially lowering the local currency proceeds of remittances and creating uncertainty about the U.S.-dollar cost of the domestic currency. This undermines the automatic stabilizer role that remittances can play during periods of exchange rate depreciation.’

Shame the political and cultural aspects of migration aren’t as straightforward. I guess the pragmatic approach is to pursue policies that maximise the developmental benefits of current migration levels, and then (if you want to) have a separate, enormous punch-up about migration and domestic politics in the North.

January 28, 2015

Why ending poverty in India means tackling rural poverty and power

Vanita Suneja, Oxfam India’s Economic Justice Lead, argues that India can’t progress until it tackles rural poverty

More than 800 million of India’s 1.25 billion people live in the countryside. One quarter of rural India’s population is below the official poverty line – 216  million people. A search for economic justice for a population of this magnitude is never going to be possible only by relying on migration to the cities. Rural-urban migration and absorption of labour in the urban economy has been slow, and will likely remain so due to the slow growth of employment, especially in labour-intensive manufacturing. The rural labour force will therefore have to find a way to improve their incomes back home in the countryside.

million people. A search for economic justice for a population of this magnitude is never going to be possible only by relying on migration to the cities. Rural-urban migration and absorption of labour in the urban economy has been slow, and will likely remain so due to the slow growth of employment, especially in labour-intensive manufacturing. The rural labour force will therefore have to find a way to improve their incomes back home in the countryside.

Agriculture is still the largest employer in rural areas. Of the total rural households (90.2 million), over half (57.8 percent) are involved in farming. In any case, rural farm and non-farm incomes have a mutual sustaining relation in the rural economy and sustenance of a strong non-farm rural economy is possible only if the agricultural economy is doing well and vice versa.

So what works in boosting the rural economy? Concentrated policy interventions including spending and reforms in extension services from 2005-2014 has shown what is possible .Average agricultural growth jumped from 2.4% during the decade 19995 to 2004 to 4% for 2005 to 2014.

But it’s not just about money – this is an area which also needs innovation and scalable pilots where grassroots civil society needs to play a much larger role . The first step is to look closely into the salient features of this sector and its actors. More than 85 % of farmers own less than 2 ha of land. These small and marginal farmers are the backbone of India’s food security and can stimulate broad based inclusive growth in rural areas.

Another feature of the farm economy is the feminization of agriculture. Though there are still more men than women in agriculture, employment data shows more men are getting out while the absolute number of women farmers in India has increased by about 62 million from 2001-2011, and now accounts for 37% of the total agricultural population.

Another feature of the farm economy is the feminization of agriculture. Though there are still more men than women in agriculture, employment data shows more men are getting out while the absolute number of women farmers in India has increased by about 62 million from 2001-2011, and now accounts for 37% of the total agricultural population.

Many women smallholders are part time farmers, earning part of their incomes from employment in the non-farm sector (typically in day work such as construction).

Incomes are very low. The government estimates average monthly incomes per agricultural household across the whole of India from July 2012- June 2013 as just Rs.6426/- ($105), out of which farming accounted for 60 percent and nearly 32 percent came from wages.

Investments and policy reforms in agriculture need to give priority to these small and marginal farmers and specifically facilitate more entrepreneurship opportunities for women. The major obstacle is often absence of land titles in their name, which hinders their access to technology, irrigation, credit and markets. It is vital that technology outreach, agricultural schemes, and information on the Minimum Support Price (MSP) are not restricted to full time big farmers but reach to part time famers especially women.

But achieving inclusive growth and prosperity in rural India is not just about farming. Forest-based employment has been seriously neglected over the years. Forest-dependent communities are often in conflict with the government’s Forest Department, demanding rights over their forest resources. Around 1/4 of the rural population including 87 million tribals, are living in and around forest areas and depend on forest resources for their livelihoods.

Sixty per cent of India’s forest area is in tribal areas. So-called ‘scheduled tribes’ lag 20 years behind the general population, display the worst indicators of child malnutrition and mortality and are at risk of becoming locked out altogether of sharing prosperity. The states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Odisha together account for 1/3rd of total tribals, ¼ of forest resources and 2/3 of minerals – conflicts around mining are commonplace.

Ending the exclusions of forest-dependent communities is hardly rocket science – they need secure access to their forests; support for building up value chains based on minor forest produce (MFP), and an end to the government forest bureaucracy’s dual control on forest resources and their sale. Though the Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006 recognized community rights over forest resources, its implementation has been systematically undermined by the Forest Department. It is important to expedite the implementation of FRA and bring further reforms under it – for example the FRA does not provide explicit rights over timber.

One progressive step has been the introduction of a government scheme to provide a Minimum Support Price (MSP) to forest dwellers for some of their products, but again, its implementation leaves much to be desired, while many important products such as tendu leaves (used to make beedi cigars) and bamboo are nationalized and under the control of the forest department.

Two external forces further threaten rural livelihoods: – Firstly, dispossession by the state for mining, industry and infrastructure; secondly, the impact of climate change on both agriculture and forestry. Safeguards to minimize forced dispossession; informed consent, resettlement, rehabilitation and adequate compensation are some of the key elements needed to protect broad-based growth in rural areas. State Action Plans on climate change and especially adaptation budgets need to be made effective and acted upon swiftly.

Climate change cannot be seen as a standalone issue, disassociated from wider issues of resilience in rural India, which in turn depends on sustained  incomes and control over natural resources such as agriculture, forestry and renewable energy – these are the essential components of a structural shift towards intra country equity and resilience to climate threats.

incomes and control over natural resources such as agriculture, forestry and renewable energy – these are the essential components of a structural shift towards intra country equity and resilience to climate threats.

Last but not least is the role of social protection programs under the Food Security Act, 2013, such as the Public Distribution System (PDS), Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), Mid-day meal scheme (MDMS) and the Maternity Benefit program in rural India. All act as safety nets, addressing malnutrition and hunger, and are a necessary condition for populations to strive for economic justice.

Demanding policies and investments for a resilient and prosperous rural India where people have dignified livelihoods still remains a transformative and necessary agenda, just as it was for Gandhi.

January 27, 2015

What are governments doing on inequality? Great new cross-country data (and some important conclusions) from Nora Lustig

Oxfam and Oxford University held a big inequality conference last week, timed to coincide with Davos and the launch of our new pre Davos briefing (massive media coverage – kudos to author Deborah Hardoon and Oxfam press team).

briefing (massive media coverage – kudos to author Deborah Hardoon and Oxfam press team).

I generally find conferences pretty disturbing. This one at least spared us the coma-inducing panels of nervous researchers reading out their papers. All the speakers were confident and convincing.

The meta-messaging at this one was great – major figures from the worlds of politics, business and academia stressing the importance of the issue and the need for action. Get this from Lady Lynn Forester de Rothschild (who started by apologising for her name – ‘I love my husband, but…..’): ‘Charlatan financiers, clueless regulators, pensioners losing their savings, CEO wages 200 times the average. Clearly things had gone wrong by the time of the 2008 crisis – collusive capitalism, big business and government colluding for their own interests is simply appalling.’

The anecdotes were pretty good too, especially on the ‘race to the bottom’ on tax incentives:

Donald Kaberuka (sadly, nearing the end of his term as President of the African Development Bank) on the experience of being Rwanda’s finance minister:

‘The multinational comes to you and says we want to invest in your country, but we need a 5 year tax holiday and this long list of requirements. And by the way, we only have 6 hours, and then our plane is taking us to your neighbour, who will probably agree to all of our demands.’

Another former Foreign Minister, Guatemala’s Juan Alberto Fuentes, had the same experience, as Costa Rica pulled the rug out from under a Central American agreement in order to do a deal with Intel.

But where was the data? Just as my powerpoint craving was getting serious, Nora Lustig rode to my rescue with a great presentation of the findings from the ‘Commitment to Equity’ research programme, which she directs. The project is ‘designed to analyze the impact of taxation and social spending on inequality and poverty in individual countries, and provide a roadmap for governments, multilateral institutions, and nongovernmental organizations in their efforts to build more equitable societies.’

Some of the more striking findings from her talk:

Cash transfers reduce inequality and do so quite substantially in some countries, e.g. South Africa, Chile, and Brazil. Direct taxes tend to be equalizing but their impact is relatively small.

Net indirect taxes (e.g., VAT, but also including energy and food subsidies and VAT exemptions) cut both ways: they increase inequality compared to

pre-tax disposable income inequality in some countries (notably, Bolivia and Guatemala) but reduce it in others (among them, Mexico and Ethiopia). See bar chart.

So much for inequality – what about poverty? Reassuringly, Nora finds that Direct Transfers (including direct taxes) reduce poverty (see the second bar chart). But the picture is more mixed with Indirect Taxes, which actually increase poverty in several countries.

I got a bit bogged down with the detail here, so tried out an impromptu executive summary with her in Q&A. We subsequently agreed via email on:

‘If governments care about inequality, they should take a holistic approach: don’t just look at individual interventions like personal income taxes or cash

transfers, and look at what tax and benefits systems do to equity both in terms of people’s cash stance (eg, cash transfers and subsidies minus direct and indirect taxes) and access to free or subsidised health and education. The best way to reduce inequality is generally to spend lots on cash transfers, health and education. Be careful with the design of indirect taxes like VAT, and worry about Poverty as well as Inequality, because sometimes, even inequality-reducing taxes can worsen poverty.’

Clear as mud?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers