Duncan Green's Blog, page 170

March 2, 2015

How can research help promote empowerment and accountability?

In the development business, DFID is a research juggernaut (180 dedicated staff, £345m annual budget, according to the ad for a new boss for its Research and Evidence Division). So it’s good news that they are consulting researchers, NGOs etc tomorrow on their next round of funding for research on empowerment and accountability (E&A). Unfortunately, I can’t make it, but I had an interesting exchange with Oxfam’s Emily Brown, who will be there, on some of the ideas we think they should be looking at. Here’s a sample:

In the development business, DFID is a research juggernaut (180 dedicated staff, £345m annual budget, according to the ad for a new boss for its Research and Evidence Division). So it’s good news that they are consulting researchers, NGOs etc tomorrow on their next round of funding for research on empowerment and accountability (E&A). Unfortunately, I can’t make it, but I had an interesting exchange with Oxfam’s Emily Brown, who will be there, on some of the ideas we think they should be looking at. Here’s a sample:

What do we need to know?

On E&A, we really need to nail down the thorny topic of measurement – how do you measure say, women’s empowerment, in a manner that satisfies the ‘gold standard’ demands of the results/value for money people? And just to complicate matters, shouldn’t a true measure of empowerment be determined by the people concerned in each given context, rather than outside funders? We’ve made some progress on such ‘hard to measure benefits’, but there’s still a long way to go.

I’d also be delighted if DFID would push a positive deviance approach on E&A: instead of NGOs or researchers promoting their preferred brand of E&A snake oil, could they first go and study the existing state of E&A, say across municipalities, and then try and understand the outliers that do particularly well/badly, as Jonathan Fox did to such good effect in Mexico?

Then there’s the question of what works – the current orthodoxy (at least in my Doing Development Differently bubble) is that purely supply side approaches (train the officials) and demand side (stoke up the protests) don’t work in isolation, so now it’s all about ‘convening and brokering’, ‘collective problem solving’ etc. But superficially at least, that contradicts other research (including Fox’s) on the importance of conflict and contestation in triggering change. Could DFID help us get to a better understanding of how the dynamics of episodes of conflict and reform interact with the process of collective problem solving?

Are Fragile States different?

If you believe Andrew Rogerson and Homi Kharas, the aid business will be increasingly focussed on fragile states, which just happen to be the hardest to work in – so there’s a big research agenda here, including on E&A.

If you believe Andrew Rogerson and Homi Kharas, the aid business will be increasingly focussed on fragile states, which just happen to be the hardest to work in – so there’s a big research agenda here, including on E&A.

Our experience is that it is often more productive to design programmes (and possibly research) in fragile and conflict states at local (community, village, municipal) rather than national level. Even in meltdowns like the DRC, we have been able to do really interesting E&A work at community level.

Beyond the question of scale, it may be that more evolutionary programming is required in fragile states (lots of multiple experiments + fast feedback and course corrections, then see where you end up). How can donors like DFID better understand and fund that sort of work? In fragile contexts, investing in people and processes may be at least as (if not more) important as the actual results at any given moment, since nice neat project outcomes can so easily be swept away by the next event.

The crackdown on civil society space

There are increasing restrictions on civic space in dozens of countries. What can outside aid agencies and INGOs do to defend domestic civil society’s license to operate? How can E&A approaches be adapted to still achieve impact when political space is minimal? One idea we are currently developing is ICT solution to map, track and respond to such restrictions.

Joining up with Governance

There’s a bit of a gulf between the way E&A people talk and the governance conversations in Doing Development Differently/Thinking and Working Politically meetings. The latter are drifting towards an alarmingly (to me) top down approach, which seems more interested in using politics to get better results – ‘small p’ rather than the big P of empowering marginalized groups. Nowhere is this more evident than on gender, which routinely goes missing in the DDD/TWP discussions on the more macho themes of institutions, reform etc, whereas gender is customarily at the heart of E&A discussions. It would be great if research could both help us understand the reasons for this disparity, and then get rid of it.

Getting NGOs to talk to Researchers

In the UK, the Research Excellence Framework, through which the government funds university research, places increasing emphasis on impact (bit of  a nightmare if your topic is 12th Century East Anglian field systems, but there we go). That ought to be pushing researchers and NGOs together – they do the research, we both have boots on the ground, and are rather good at all that noisy message and comms stuff. But there is still a gulf in ways of working, language, respect, incentives, timescales etc that makes such partnerships really difficult – could DFID consciously promote such partnerships, for example by giving brownie points to joint funding applications?

a nightmare if your topic is 12th Century East Anglian field systems, but there we go). That ought to be pushing researchers and NGOs together – they do the research, we both have boots on the ground, and are rather good at all that noisy message and comms stuff. But there is still a gulf in ways of working, language, respect, incentives, timescales etc that makes such partnerships really difficult – could DFID consciously promote such partnerships, for example by giving brownie points to joint funding applications?

And of course (Emily would kill me if I don’t say this), they should definitely fund research linked to Oxfam’s fantastic Raising Her Voice project on women’s empowerment, which Emily manages (see below for funky RSAnimate style intro).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?wmode=t...” width=”WIDTH” height=”HEIGHT” >

And if you have any other E&A related research issues you want to raise, feel free – we can always pass them on. [and a big thanks to Jo Rowlands and Ross Clarke for their additions to this post].

March 1, 2015

Links I Liked

Forget mixed panels, how often do you see this at a conference? (although a crèche might have made her life easier…..) [h/t Rahma M Mian]

Wonder what Dominique Strauss-Kahn would make of the IMF’s new report on national restrictions on women’s rights

‘Number of wrecked airplanes near the runway of the main airport’. Crowd-sourced “Real World Development Indicators” from Chris Blattman

Map of African regime types, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index (27/54 countries are ”authoritiarian/nominal democracy’)

Anti-drug policies cost $100bn a year, don’t work, and often harm poor farmers and the environment according to a new Health Poverty Action report

From the perils of micromanagement to the wonders of cash transfers: great 7 part rethink of aid by former USAID staffer Diana Ohlbaum

David Booth of ODI summarizes big research project with ’5 myths about governance and development‘, including that there is no evidential basis for David Cameron’s ‘golden thread’ argument that one leads to the other.

American Dream v social mobility reality, all done with lego. Smart 4m video from Richard Reeves at the Brookings Institution. Wd love to see ones for BRICS, UK etc

February 26, 2015

Why premature deindustrialization is really bad news for development

One of the many positives about development is that lots of good stuff is happening much earlier in a country’s trajectory – on average, falling infant  mortality, access to healthcare and education, rights, democracy etc all take place at lower levels of GDP per capita than in the past. Unfortunately, guru economist Dani Rodrik has also found something not so positive following the same pattern – premature deindustrialization. Here are some excerpts from his new paper.

mortality, access to healthcare and education, rights, democracy etc all take place at lower levels of GDP per capita than in the past. Unfortunately, guru economist Dani Rodrik has also found something not so positive following the same pattern – premature deindustrialization. Here are some excerpts from his new paper.

From the Abstract:

‘The hump‐shaped relationship between industrialization (measured by employment or output shares) and incomes has shifted downwards and moved closer to the origin (see graph below). This means countries are running out of industrialization opportunities sooner and at much lower levels of income compared to the experience of early industrializers. Asian countries and manufactures exporters have been largely insulated from those trends, while Latin American countries have been especially hard hit. Advanced economies have lost considerable employment (especially of the low‐skill type), but they have done surprisingly well in terms of manufacturing output shares at constant prices. While these trends are not very recent, the evidence suggests both globalization and labor‐ saving technological progress in manufacturing have been behind these developments. Premature de‐industrialization has potentially significant economic and political ramifications, including lower economic growth and democratic failure. ‘

Skip all the equations, and get to this from the conclusions:

‘Premature deindustrialization is not good news for developing nations…. The consequences are already visible in the developing world. In Latin America, as manufacturing has shrunk informality has grown and economy‐wide productivity has suffered. In Africa, urban migrants are crowding into petty services instead of manufacturing, and despite growing Chinese investment there are as yet few signs of a real resurgence in industry. Where growth occurs, it is driven largely by capital inflows, transfers, or commodity booms, raising questions about its sustainability.

‘Premature deindustrialization is not good news for developing nations…. The consequences are already visible in the developing world. In Latin America, as manufacturing has shrunk informality has grown and economy‐wide productivity has suffered. In Africa, urban migrants are crowding into petty services instead of manufacturing, and despite growing Chinese investment there are as yet few signs of a real resurgence in industry. Where growth occurs, it is driven largely by capital inflows, transfers, or commodity booms, raising questions about its sustainability.

In the absence of sizable manufacturing industries, these economies will need to discover new growth models. One possibility is services‐led growth. Many services, such as IT and finance, are high productivity and tradable, and could play the escalator role that manufacturing has traditionally played. However, these service industries are typically highly skill‐intensive, and do not have the capacity to absorb – as manufacturing did – the type of labor that low‐ and middle‐income economies have in abundance. The bulk of other services suffer from two shortcomings. Either they are technologically not very dynamic. Or they are non‐tradable, which means that their ability to expand rapidly is constrained by incomes (and hence productivity) in the rest of the economy.

The political consequences of premature deindustrialization are more subtle, but could be even more significant. Historically, industrialization played a foundational role in Europe and North America in creating modern states and democratic politics. Its relative absence in today’s developing societies could well be the source of political instability, fragile states, and illiberal politics.’

Rodrik admits he’s on ‘speculative ground’ when discussing possible links between deindustrialization and politics, but I’m pleased to say he doesn’t let  that stop him. The premature disappearance of an industrial proletariat (historically, the basis for unions and social democracy) has profound political implications:

that stop him. The premature disappearance of an industrial proletariat (historically, the basis for unions and social democracy) has profound political implications:

‘Politics looks very different when urban production is organized largely around informality, a diffuse set of small enterprises and petty services. Common interests among the non‐elite are harder to define, political organization faces greater obstacles, and personalistic or ethnic identities dominate over class solidarity. Elites do not face political actors that can claim to represent the non‐elites and make binding commitments on their behalf. Moreover, elites may prefer – and have the ability – to divide and rule, pursuing populism and patronage politics, and playing one set of non‐elites against another. Furthermore, elites themselves may be much more divided, based on clans or other loyalties. Consequently, grand political bargains become less likely. Political institutions remain fragile and personalized. In short, premature deindustrialization may hamper both the development of middle‐ class values and the emergence of political settlements that allowed the consolidation of democracy in today’s advanced countries.

On the face of it, this conclusion appears to be contradicted by the spread of democracy around the world. More countries in the developing world are formally democratic today than has ever been the case. However, upon closer look, political life in many if not most of these countries is marred by civil rights abuses and popular discontent that periodically erupts in protests and riots. Governments pursue an illiberal brand of politics and are democratic only in name. For the most part, democracy in the developing world remains either a within‐elite affair or takes the form of populism.’

Brilliant, if depressing. Sorry.

February 25, 2015

My Friend Died Last Week – Tax Could Have Saved His Life

My colleague Max Lawson (@maxlawsontin ), Oxfam’s head of global policy and campaigns, lost a friend to illness recently, and wrote this fine, angry polemic  in response (it appeared earlier this week in Huffpo):

in response (it appeared earlier this week in Huffpo):

My friend died last week. Mr Kumambala was a great man, who had taught mathematics to Malawi’s children for more than forty years. His huge smile and loud gasps and gesturing on every topic are unforgettable. Being one of two black men to do his Masters in Hull in 1986: ‘Lawson- there were so many whites! Crowding around! Pointing! And many of them were poor!’ Or my atheism: ‘ Lawson- you are a foolish boy- who do you think created you?’ To Malawian politics: ‘ Our politicians are thieves, our system is buggered!’ I will miss him terribly.

He was a kind, committed, decent man, and he died completely unnecessarily, for want of basic healthcare. Mr Kumambala was diabetic, and a combination of malaria and very low blood sugar killed him. It simply should not have happened. A fit man, full of life, with so much left to give. Cut down when basic medicine and simple healthcare would have saved his life.

At the same time last week we have all learned in detail the Swiss secrets of the filthy rich, hiding their millions away to avoid tax. I think we should stop talking about these seemingly endless taxation scandals in terms of dollars, euros or pounds as the currency to quantify the costs. Instead I would like to propose a new currency, the nurse, with perhaps the hospital as the larger denomination. Imagine the headlines on the Guardian front page:

‘Revealed: millionaire Ritchie Rich used Swiss Account to avoid 20,000 nurses worth of tax in one year’ Or ‘The Banana Corporation used the Cayman Islands to avoid paying any tax on its record profits. The taxation avoided was valued at around 400 hospitals’

The New Economics Foundation calculated that for every £1 of value generated by a tax accountant they destroy £47. By contrast, a hospital cleaner creates ten pounds of social value for every pound they are paid. How would a tax accountant feel I wonder if, instead of sitting in an office in front of an excel spreadsheet, when they got to the office one day they were directed downstairs and asked to climb into the cab of one of those cranes with a wrecking ball attached, and actually destroy a school? Or personally sack a thousand teachers? Unscrupulous tax accountants are like the drone operators of the financial world, spending their days helping clients defraud societies of billions at the click of a mouse before picking up their jackets and rushing to Waterloo to get the 18.30 train home.

The New Economics Foundation calculated that for every £1 of value generated by a tax accountant they destroy £47. By contrast, a hospital cleaner creates ten pounds of social value for every pound they are paid. How would a tax accountant feel I wonder if, instead of sitting in an office in front of an excel spreadsheet, when they got to the office one day they were directed downstairs and asked to climb into the cab of one of those cranes with a wrecking ball attached, and actually destroy a school? Or personally sack a thousand teachers? Unscrupulous tax accountants are like the drone operators of the financial world, spending their days helping clients defraud societies of billions at the click of a mouse before picking up their jackets and rushing to Waterloo to get the 18.30 train home.

On a global scale, tax dodging is depriving poor countries of hundreds of millions and often billions of dollars each year, as individuals and corporations are allowed to hide their money away and avoid paying tax. Last week’s HSBC scandal involved huge numbers for countries like the UK, but there were secret accounts for individuals from countries all over the world.

The figure for Malawi is $16.1 million dollars. It is not clear whether the Malawi money in the Swiss accounts is there legally- for many countries the money has been taken from governments illegally as the result of corruption- in which case it should all be returned. But even if we assume it is all legal in the Malawi case then it should be taxed. At the top Malawian income tax rate of 30 percent this would, by my rough reckoning, pay the salaries of 800 nurses.

And last week’s leak is just a tiny glimpse of this massive problem. Through tax dodging, billions in wealth is systematically redistributed upwards to the 1 percent with those at the top paying little if any tax, leading to obscene levels of wealth and inequality.

So for me it is simple. I will not accept a world where the wealthy are allowed to collude with their cashiers to squirrel away billions to gather dust in vaults in Geneva, when that money could have paid for insulin to save my friend.

February 24, 2015

8 myths about non-violent activism (from a movement that overthrew a dictator)

I’m still catching up on the email backlog after returning from holiday, but while I’m doing so, here’s something I should probably do more of – a straight lift from a really interesting article.

lift from a really interesting article.

I recently signed up to the New York Times ‘Fixes’ column (‘solutions to social problems and why they work’). On a bad week, it can be a bit ‘Ted talks’ – whizzy tech solutions that underplay power and politics. But last week brought a fascinating piece on the myths around non-violent action, based on the work of Otpor (right), the Serbian movement that helped overthrew Slobodan Milosevic in 2000. Otpor’s leaders have since founded the Center for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (Canvas), training democracy activists from 46 countries, including a group of Syrian activists who attended a workshop with the NYT authors some years before the current bloodbath began. Some highlights:

Myth: Nonviolence is synonymous with passivity.

No, nonviolent struggle is a strategic campaign to force a dictator to cede power by depriving him of his pillars of support.

In the first hours of the Syrians’ workshop, some participants announced that violence was the only way to topple Assad. Every workshop begins this way, in part because some people think the Serbs are going to teach them to look beatific and meditate. [Otpor leader Srdja] Popovic said out loud what many were thinking: “So you just ask Assad to go away? Please, Mr. Assad, please can you not be a murderer anymore?” Popovic whined. “It’s not nice.”

Just the opposite, said Djinovic: “We’re here to plan a war.” Nonviolent struggle, Djinovic explained, is a war — just one fought with means other than weapons. It must be as carefully planned as a military campaign.

Myth: The most successful nonviolent movements arise and progress spontaneously.

No general would leave a military campaign to chance. A nonviolent war is no different.

Myth: Nonviolent struggle’s major tactic is amassing large concentrations of people.

This idea is widespread because the big protests are like the tip of an iceberg: the only thing visible from a distance. Did it look like the ousting of Mubarak started with a spontaneous mass gathering in Tahrir Square? Actually, the occupation of Tahrir Square was carefully planned, and followed two years of work. The Egyptian opposition waited until it knew it had the numbers. Mass concentrations of people aren’t the beginning of a movement, Popovic writes. They’re a victory lap.

In very harsh dictatorships, concentrating people in marches, rallies or protests is dangerous; your people will get arrested or shot. It’s risky for other reasons. A sparsely attended march is a disaster. Or the protest can go perfectly, but someone — perhaps hired by the enemy — decides to throw rocks at the police. And that’s what will lead the evening news. One failed protest can destroy a movement.

In very harsh dictatorships, concentrating people in marches, rallies or protests is dangerous; your people will get arrested or shot. It’s risky for other reasons. A sparsely attended march is a disaster. Or the protest can go perfectly, but someone — perhaps hired by the enemy — decides to throw rocks at the police. And that’s what will lead the evening news. One failed protest can destroy a movement.

So what do you do instead? You can start with tactics of dispersal, such as coordinated pot-banging, or traffic slowdowns in which everyone drives at half speed. These tactics show that you have widespread support, they grow people’s confidence, and they’re safe. Otpor, which went from 11 people to 70,000 in two years, initially grew like this: three or four activists staged a humorous piece of anti-Milosevic street theater. People watched, smiled — and then joined.

Myth: Nonviolence might be morally superior, but it’s useless against a brutal dictator.

Nonviolence is not just the moral choice; it is almost always the strategic choice. “My biggest objection to violence is the fact that it simply doesn’t work,” Popovic writes. Violence is what every dictator does best. If you’re going to compete with David Beckham, Popovic says, why choose the soccer field? Better to choose the chessboard.

The scholars Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan analyzed campaigns of violent and nonviolent revolution in the last century (their book, “Why Civil Resistance Works,” uses Otpor’s fist as its cover image) and found that nonviolence has double the success rate of violence — and its gains have been more likely to last.

Only a handful of people will join a violent movement. Using violence throws away the support of millions — support you could have won through

Syria: would non violence have worked any better?

nonviolence.

Milosevic’s base of support was Serbia’s senior citizens. Otpor won them over by provoking the regime into using violence. Once Otpor’s leaders realized that its members who were arrested were usually released after being held for a few hours, it staged actions for the purpose of getting large numbers of members detained. Grandparents didn’t like having their 16-year-old grandchildren arrested, or the regime’s hysterical accusations that these high school students were terrorists and spies. Old people switched sides, becoming a key pillar of the Otpor movement. If there had been any truth to the accusations that Otpor used violence, the grandparents would have stayed with Milosevic.

Myth: Politics is serious business.

Nothing breaks people’s fear and punctures a dictator’s aura of invincibility like mockery — Popovic calls it “laughtivism.” Otpor’s guiding spirit was Monty Python’s Flying Circus, a television show its members had grown up watching, and its actions were usually pranks.

Popovic writes about a protest in Ankara after the Turkish government reacted with alarm to a couple kissing in the subway. Protesters could have chosen to march. Instead, they kissed – 100 people gathered in the subway station in pairs, kissing with great slobber and noise. You are a policeman. You have training in how to deal with an anti-government protest. But what do you do now?

Myth: You motivate people by exposing human rights violations.

Most people don’t care about human rights. They care about having electricity that works, teachers in every school and affordable home loans. They will support an opposition with a vision of the future that promises to make their lives better.

Focusing on these mundane, important things is not only more effective; it’s safer. In their Canvas workshop, the Burmese knew it was too risky to organize for political goals — but decided they could organize to get the Yangon city government to collect garbage. Gandhi wisely began his campaign of mass civil disobedience by focusing on Britain’s prohibition on collecting or selling salt. Harvey Milk failed in several campaigns for the San Francisco City Council. He won when he campaigned not on gay rights, but to rid the city’s parks of dog poop. A benefit of such campaigns is that their goals are achievable. Movements grow with small victory after small victory.

Gandhi’s salt march

Talking about the miseries of life under a dictator is also a bad strategy for mobilizing activists. People already know — and they react by becoming cynical, fearful, atomized and passive. They might be angry, but they’re not going to act on it. Anger is not a motivator.

This was Otpor’s biggest obstacle. Most Serbs wanted Milosevic out. But the vast majority believed that was impossible to accomplish, and too perilous to attempt.

Otpor got people into the streets by making the movement about their own identity. Young people flocked to Otpor because it made them feel cool and important. They had great music and great T-shirts, adorned with the fist. Boys competed to rack up the most arrests. Young Serbs stopped feeling like passive victims and started feeling like daring heroes.

Myth: Nonviolent movements require charismatic leaders who give inspiring speeches.

Otpor had no speeches, ever. And while its strategies were meticulously planned, the people who did the planning were behind the scenes. Its spokesperson changed every two weeks, but it was usually a 17-year-old girl. (“Terrorists? Us?”)

Myth: Police, security forces and the pro-government business community are the enemy.

Maybe, but it’s smarter to treat them like allies-in-waiting. Otpor never taunted or threw stones at the police. Its members cheered them and brought flowers and homemade cookies to the police station. Even the interrogations after arrest were an opportunity to fraternize and demonstrate Otpor’s commitment to nonviolence.

It paid off. The police knew that if the opposition won, Otpor would make sure they were treated fairly. During the last battle, police officers walked away from the barricades when the opposition asked them to. A dictator who can’t be sure his repressive orders will be obeyed is finished.

February 18, 2015

What happens if we apply doughnut economics to single countries, starting with the UK?

Katherine Trebeck (@ktrebeck), Oxfam policy adviser and all round well-being guru, reports on a new effort to apply doughnut economics at a national scale, starting with the UK

Every so often, a simple idea catches people’s imagination. Complex concepts get distilled into a mantra or image that elicits an ‘a ha’ moment. World views can be changed. Perspectives shifted. And ideologies dented.

Such was the case when Oxfam GB published a report entitled A Safe and Just Operating Space for Humanity. Its author, Kate Raworth, introduced the now famous

‘doughnut’ (right) – a space below a planetary boundaries and above a social floor in which humanity can thrive.

It is a great image – it highlights that faster GDP growth without regard to its quality or distribution is not only unsustainable, but potentially (and often) disconnected to conditions in which people can build lives worth living.

Since its release it has been picked up by policy makers, civil society, businesses and academia. It offers a new goal, perhaps even a compass for the direction of our economy and goals of our policy making.

But, moving beyond that isn’t easy. The doughnut is great way of putting flesh on the bones of the term ‘sustainable development’, bringing together environmental and social considerations in a single framework. But then what? For starters, most of the decisions that matter are taken at a national, rather than planetary level.

So Oxfam has been exploring ways to downscale the doughnut concept to the national level – putting some numbers to the idea to see the extent to which a country operates within that safe and just space.

Today we launch our report for the UK (Scotland launched theirs in 2014, and Wales, Brazil and South Africa are on the case – we’ll keep you posted).

Inevitably there were some challenges in bringing the concept of Planetary Boundaries to the national level in a way relevant to the UK. So we tried to pragmatically find a way forward. We also sought to posit elements of the social floor that made sense in the UK context – and for us, this meant taking account of what people – not just experts – identify as important . To do so we drew on work that engaged with the public about what they identified as necessities in the UK, or what was needed to live well in the UK, or what sort of areas of life are important to wellbeing in the UK. The full report sets out all the decisions we took and the datasets we looked at, but we’d be keen to hear from anyone who can recommend improvements to our evidence base.

So how does the UK shape up?

The picture painted by the UK Doughnut model is stark. The UK’s impact upon planetary boundaries is far beyond what its population size can justify. The UK significantly outstrips proposed boundaries in nearly all of the environmental domains identified – by 55% in terms of biodiversity loss (measured via the decline of farmland birds); by 64% of in terms of ocean health (measured via the percentage of UK fish harvested unsustainably); by 250% in terms of land use change; and by 410% in terms of climate change (measured by emissions of MtCO2/year). There’s a bit of good news in terms of ozone depletion in that the UK does not emit discernable quantities – a reminder that when there is political will, change can happen.

The picture painted by the UK Doughnut model is stark. The UK’s impact upon planetary boundaries is far beyond what its population size can justify. The UK significantly outstrips proposed boundaries in nearly all of the environmental domains identified – by 55% in terms of biodiversity loss (measured via the decline of farmland birds); by 64% of in terms of ocean health (measured via the percentage of UK fish harvested unsustainably); by 250% in terms of land use change; and by 410% in terms of climate change (measured by emissions of MtCO2/year). There’s a bit of good news in terms of ozone depletion in that the UK does not emit discernable quantities – a reminder that when there is political will, change can happen.

At the same time, inequalities in the distribution of the UK’s wealth are causing deprivation across many indicators as people find themselves out of work, unable to afford to heat their homes and forced to visit food banks or simply go without enough food. The report shows that 23% of the adult population lack any formal qualification; over a quarter of households are in fuel poverty; almost two thirds (59%) of people feel they have no say in what the government does; and over half of people do not access the natural environment each week.

Oxfam’s UK Doughnut demonstrates that our current economic model is, in many ways, both environmentally unsafe and socially unjust.

Oxfam’s UK Doughnut demonstrates that our current economic model is, in many ways, both environmentally unsafe and socially unjust.

However, the situation we currently face is not set in stone. Choices can be made to develop a more environmentally sustainable future. And many of the failures on the social floor are the result of the way we currently organize our society. They are the result of successive governments’ policy choices on how we use the tax system and public spending, how we regulate and deliver services, what we expect of business, and how we provide support for our citizens.

So far, so good. The next step is to not only identify policies and actions that can help us step off the ‘growth at any cost’ treadmill, but encourage and facilitate them.

February 15, 2015

Links I Liked

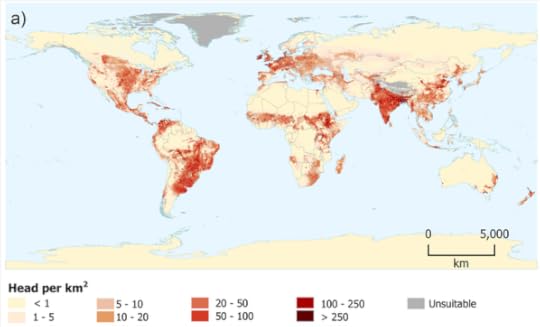

Livestock demography: where do the world’s 1.4 billion cows, 19.6 billion chickens & 0.98 billion pigs live? Here’s the cows

Tolkien’s ‘one ring to rule them all’ as a parable for the attractions and perils of new technologies

UK aid watchdog criticises DFID for its efforts to expand work in fragile states, but accepts real impact will ‘take a generation’

No we are not all born equal. Smart 3 minute video explainer on US inequality.

Anthropologists v therapists – who has the best approach to helping people cope with post-disaster/conflict trauma?

Contrasting stories of mining activism:

What happens when a small NGO uses the OECD’s Contact Point mechanism to try and hold a big mining company to account in Bangladesh?

A British gold mining firm agrees (undisclosed) settlement over the deaths of Tanzanian villagers

Why won’t you slap her? Powerful campaign video from Italy – leaves me feeling bit uneasy though (but maybe that’s just because it’s so Italian)

Right, I’m off on holidays for a week or so – couple of p0sts scheduled while I’m away, but otherwise, back in action next week.

February 12, 2015

What do we know about the politics of reducing inequality? Not much – it’s time to find out

Spent a fun day at the Developmental Leadership Program annual conference in Birmingham yesterday. I was on a panel pitching an idea for a research programme that has got me very excited (along with David Hudson and Niheer Dasandi from University College London). Here’s my pitch.

has got me very excited (along with David Hudson and Niheer Dasandi from University College London). Here’s my pitch.

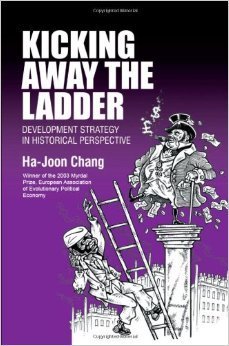

One of my formative influences as a policy wonk was watching the impact of Ha-Joon Chang’s great book Kicking Away the Ladder on the Doha round of global trade talks. Ha-Joon showed how all the rich countries that were using the WTO to urge poor countries to liberalize had done precisely the opposite when they themselves were on the way up. Germany protected infant industries, while in the US Alexander Hamilton more or less invented industrial policy.

The book came out in 2002, shortly after the launch of the Doha Round, and Ha-Joon was a regular visitor to the WTO in Geneva, where developing country delegates lapped up his message. We even co-authored a paper on the rich countries’ efforts to introduce investment rules at the WTO with the subtitle ‘Do as we Say, Not as we Did’. I have no idea how you would set about proving it, but I am sure Ha-Joon’s writings helped strengthen their resolve to resist the pressure for premature liberalization.

A few other books have similarly mined history to discover the policies of now successful countries – Oxfam used Development with a Human Face by Santosh Mehrotra and Richard Jolly, as a key source for understanding how countries achieved universal access to health and education. Then last year of course, we had Thomas Piketty, and suddenly everyone was talking about the history of inequality and the case for redistribution, wealth taxes etc.

A few other books have similarly mined history to discover the policies of now successful countries – Oxfam used Development with a Human Face by Santosh Mehrotra and Richard Jolly, as a key source for understanding how countries achieved universal access to health and education. Then last year of course, we had Thomas Piketty, and suddenly everyone was talking about the history of inequality and the case for redistribution, wealth taxes etc.

The point about looking at the origins of historical success on any given topic is that it liberates us to think about, and propose a wider range of policy options than whatever is the received wisdom of the day. I would love to see a whole series of ‘lessons of history’ books – on tax reform, welfare systems, rights etc etc. So let’s start with inequality, given that it is top of everyone’s agenda right now.

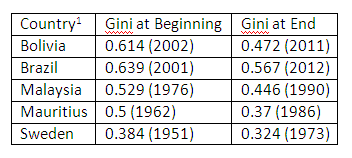

The historical narrative we currently use to discuss what to do about inequality is limited and Northern – the New Deal in the US and the origins of the UK welfare state are far too prominent, perhaps with recent improvements in Brazil lobbed in. But a quick scan of the numbers shows that there are many more episodes of redistribution to look at (see table for some other candidates).

But as well as looking at the policies involved, we want to go one step further. What were the politics that meant that these countries,  at these moments, started to tackle inequality? And what were the politics that led to the end of those efforts?

at these moments, started to tackle inequality? And what were the politics that led to the end of those efforts?

As a warm up I spent a day in the British Library and looked at the 5 countries in the table. On a quick skim of the history of their redistributive experiments, I identified some possible common factors for further study:

New political parties, often linked to social movements (Brazil, Bolivia) and/or peasant parties (Sweden)

Shocks (race riots in Malaysia) and big political transitions (demilitarization in Brazil)

Existential threats (Russian Revolution in Sweden)

New constitutions that changed the nature of politics (Brazil, Bolivia)

Malaysia’s shock, 1969

And some things which you might have expected to be a problem, but weren’t

Curse of Wealth – big commodity booms in Bolivia and Brazil coincided with redistribution

Ethnic Diversity: Malaysia and Mauritius were both ethnically divided, but able to redistribute. In fact it may even be the case that having political and economic power in the hands of different groups can lead to them having to do a deal (though it can also lead to conflict – we need to try and understand what determines the way it goes).

The discussion in Birmingham added a lot of new angles to this initial pitch:

Decentralization in the run up to the distribution period, in encouraging localized policy experimentation, which helped develop tools like cash transfers and participatory budgeting in Brazil

‘Coalitions of commitment’ bringing together state insiders and grassroots outsiders to push through redistributive programmes.

Narratives, national myths, and the use of symbols to generate momentum and weaken opposition to reforms.

The spread of primary and secondary education in reducing the return to skills (i.e. more educated people, so the wage differential between skilled and unskilled falls, bringing down income inequality). Big factor in Brazil, apparently.

But perhaps the biggest new element was Frances Stewart’s work on horizontal v vertical inequalities. Horizontal inequalities affect groups – based on ethnicity, gender, region etc, whereas vertical inequalities are between individuals, e.g. income, wealth. Frances thinks we will find that horizontal inequalities are often the triggers for redistribution (eg race riots in Malaysia), but the impact of subsequent reforms affects both. We’ll need to explore both kinds of inequality in the case studies.

There were some other intriguing questions raised, which hopefully the research can try to answer – was falling inequality a conscious aim of the government, or an unintended, but happy consequence of something else, eg a shift to labour intensive manufacturing in pursuit of growth (Mauritius, Malaysia)? How much of this was about serendipity – a fortunate combination of circumstances, rather than conscious politics or policy?

Over the next few months, we’ll be refining the methodology for the case studies and looking for authors with specialist knowledge of the countries concerned – get in touch if you’re interested, or have any suggested reading (preferably on the politics – I think we’ve got the policies covered).

February 11, 2015

If annoying, talking down to or ‘othering’ people is a terrible way to influence them, why do we keep doing it? (research edition)

I’ve been thinking about how we criticize/critique people, groups and ideas recently. It started with a conversation with my pal Chris Roche who first expressed surprise at the snarky tone of my post on a paper on NGOs (What can we learn from a really annoying paper on NGOs and development?) and then pronounced himself a bit irritated by some of the ‘Doing Development Differently’ messaging, which he sees as largely repackaging (and taking the credit for) approaches that assorted practitioners have been using and promoting for decades.

the snarky tone of my post on a paper on NGOs (What can we learn from a really annoying paper on NGOs and development?) and then pronounced himself a bit irritated by some of the ‘Doing Development Differently’ messaging, which he sees as largely repackaging (and taking the credit for) approaches that assorted practitioners have been using and promoting for decades.

The paper I bashed last year has been revised and appeared in World Development, along with a note saying ‘The writers were inspired to write the article after a recent working paper by Banks and Hulme was criticized on a widely read blog’ (yep, that would be me). Its content is a lot better in this new version (possibly because they’ve pulled in Mike Edwards as a co-author), but as I read it I still found my hackles rising, because although the content has improved, the tone has not. Stating the blindingly obvious as though it’s a major discovery; assuming all NGOs are venal, stupid or both; not acknowledging any differences within and between NGOs; not consulting NGOs or reading their internal literature. Teeth-grindingly annoying.

So what? Well, alienating your audience to this degree is a pretty terrible way to influence anyone – taking myself as a proxy for the target audience (the paper is arguing that NGOs need to sharpen up their act) I found it really hard to read and take in the messages of the paper through my cloud of irritation.

And the experience of being on the receiving end in this case made me think about all the times NGOs (including me) dish it out in much the same way – to the World Bank, the IMF, the ‘private sector’, ‘banks’, ‘economists’. I fear we do exactly the things I have just criticised the paper’s authors of doing – talking about ‘the private sector’ as though it’s one thing; saying ‘growth is all about people’ as though only NGOs get it; either not sending the paper to the target, or sending it two days before publication so there’s not time to revise it, however good their response.

Why do we do this? Some reasonable explanations, and some less so. On the reasonable side, you need a clear consistent narrative for campaigns, and there is no doubt that Robin Hood-style campaigning (we are heroic outlaws, they are the Sheriff of Nottingham) is coherent and effective in getting media coverage. Try writing a press release saying ‘hey they’re all different, but some are worse than others and could improve’. And in some cases you’re not looking to ‘engage’, but to build up a big and noisy opposition – in that case polarization is good.

But I fear other factors are at play in the way we ‘other’ our targets. A lack of self confidence/fear of being coopted makes it tempting to divide the world up into us and them. There’s also the common psychological phenomenon called splitting where people find it easier to divide world into Good and Bad. Who would campaign about shades of grey? ‘Speaking Truth to Power’ can sometimes be heroic and necessary, but it can also be counter-productive and even self indulgent, if by alienating power, it closes off possible paths to change.

But I fear other factors are at play in the way we ‘other’ our targets. A lack of self confidence/fear of being coopted makes it tempting to divide the world up into us and them. There’s also the common psychological phenomenon called splitting where people find it easier to divide world into Good and Bad. Who would campaign about shades of grey? ‘Speaking Truth to Power’ can sometimes be heroic and necessary, but it can also be counter-productive and even self indulgent, if by alienating power, it closes off possible paths to change.

As for Chris’ ‘old wine in new bottles’ problem, the academic incentives are all aligned behind saying ‘I have a new theory/concept/approach’ rather than ‘I’ve tweaked this idea that’s been around for a while but hasn’t been taken seriously’. In any case, academics are much more likely to get noticed, and so achieve wider impact with their work, if they follow that route. Tricky – my feeling is that if you see some bigger fish stealing your ideas, you should congratulate them for their amazing new insights, quietly pat yourself on the back, kick the cat (if you need to get it out of your system) and move on.

So what might good practice look like?

- Assume the people you are criticizing are as smart as you, and that some of them at least will already have thought about these criticisms

- Seek them out and try and involve them in your work as early as possible

- Find out what the sector (or your predecessors) has said/written on your issue and acknowledge it

- Avoid lazy generalizations – be specific about what and who you are criticizing

Thoughts?

February 10, 2015

Why making an assassinated Archbishop into a Saint is a great victory for social justice (and not just for Catholics)

No-one does long term campaigning better than faith groups – the Quakers led the anti-slavery struggle for 50 years in the early 1800s. As for the Catholics, when your  institution is a couple of thousand years old, you tend to take the long view.

institution is a couple of thousand years old, you tend to take the long view.

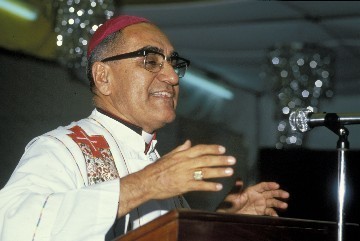

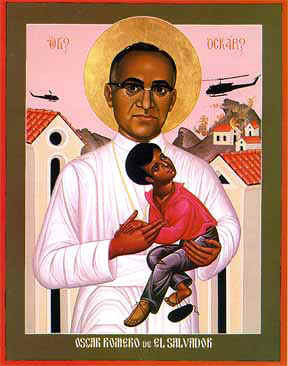

I thought of this last week, as I cycled past ‘Romero Close’ – site of the old office of my former employer CAFOD, the Catholic aid agency for England and Wales (where I was the token atheist). CAFOD spent several years persuading the council to rename its entrance alleyway after Oscar Romero, the archbishop of San Salvador assassinated by right wing ‘death squads’ in 1980. That keeps his name in the public eye (albeit in a small way), for decades (maybe even a century or two).

But now, Julian Filochowski, Clare Dixon other CAFOD stalwarts have a much greater victory. Last week, the Vatican formally declared that Romero died as a martyr, killed ‘out of hatred of the faith’. That puts him definitively on the (very convoluted) road to sainthood (apparently, being declared martyred means you don’t have to have performed miracles to be declared a saint). The formal process has taken 20 years and been blocked at every turn by conservatives within the Church, who feared canonizing Romero would effectively canonise liberation theology, which they had spent their whole lives trying to extinguish. Now they have lost. Here is a reminder (from my book Faces of Latin America) of what all the fuss was about:

‘On the economy

‘The cause of all our ills is the oligarchy – that handful of families who care nothing for the hunger of the people but need that hunger in order to have cheap, abundant labour to raise and export their crops.’

On violence

‘Profound religion leads to political commitment, and in a country such as ours where injustice reigns, conflict is inevitable.… Christians have no fear of combat; they know how to fight but they prefer to speak the language of peace. Nevertheless, when a dictatorship violates human rights and attacks the common good of the nation, when it becomes unbearable and closes all channels of dialogue, of understanding, of rationality: when this happens, the Church speaks of the legitimate right of insurrectional violence.’

On 23 March 1980 he signed his death warrant by appealing directly to the soldiers carrying out attacks on innocent civilians:

‘In the name of God, and in the name of this suffering people whose laments rise to heaven every day more tumultuous, I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression.’

The next day he was killed with a single shot while saying mass in the chapel of the cancer hospital where he lived.’

The next day he was killed with a single shot while saying mass in the chapel of the cancer hospital where he lived.’

The people of El Salvador didn’t wait for the Pope’s permission to declare Romero a saint – within a few years of his death, I visited his tomb in the Cathedral in San Salvador, and found it festooned with messages from the faithful, thanking him for answering their prayers to be cured of sickness, to find jobs and a hundred other blessings.

Why does all this matter (and not just for Catholics)? Because the conservatives were right – canonizing Romero does recognize the progressive nature of his message as an essential aspect of Catholicism, not just under this Pope, but all those that follow. Symbolism and faith go much deeper into people’s hearts and values than all our clever policy papers (though CAFOD does them too) and will leave a legacy for centuries – kudos to Julian, Clare and the hundreds of other campaigners in El Salvador and around the world. 35 years well spent.

And here’s a pumped up Clare Dixon, in San Salvador on the day of the announcement, reflecting on Romero’s legacy, and CAFOD’s role

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers