Duncan Green's Blog, page 169

March 17, 2015

The best synthesis so far of where we’ve got to on ‘Doing Development Differently’

Finally got round to reading the ‘Adapting Development’ the ODI’s latest 54 page synthesis of the theory and practice underpinning the ‘Doing  Development Differently’ approach. It’s very good – a good lit review, laced with lots of case studies and good insights – and definitely worth a careful read. Weirdly the bit that jumped out for me was on results and monitoring (see below):

Development Differently’ approach. It’s very good – a good lit review, laced with lots of case studies and good insights – and definitely worth a careful read. Weirdly the bit that jumped out for me was on results and monitoring (see below):

The starting point is that ‘Change is almost always driven by domestic forces, and often occurs incrementally, as a result of marginal shifts in the ways interests are perceived, especially by elites.’

ODI argues that ‘the best approach for domestic reformers and their supporters combines three key ingredients.

• Working in problem-driven and politically informed ways. This might seem obvious but is rarely the norm. Such an approach tracks down problems, avoids ready-made solutions and is robust in its assessment of possible remedies. Too often, diagnosis only gets as far as uncovering a serious underlying challenge – often linked to the character of local politics. For example, studies of medicine stock outs in Malawi and Tanzania and of human resources for health in Nepal reveal how power, incentives and institutions lead to chronic gaps in supply. It is difficult to identify workable solutions to such problems, and attempts to do so often focus on the wrong things. Doing things differently means understanding what is politically feasible and discovering smart ways to make headway on specific service delivery issues, often against the odds.

• Being adaptive and entrepreneurial. Much development work fails because, having identified a problem, it does not have a method to generate a viable solution. Because development problems are typically complex and processes of change are highly uncertain, it is essential to allow for cycles of doing, failing, adapting, learning and (eventually) getting better results. This requires strong feedback loops that test initial hypotheses and allow changes in the light of the result of those tests. Some of the greatest success stories in international development – the South Korean industrial policy being only one example – are the result of a willingness to take risks and learn from failure.

• Supporting change that reflects local realities and is locally led. Change is best led by people who are close to the problem and who have the greatest stake in its solution, whether central or local government officials, civil-society groups, private-sector groups or communities. While local ‘ownership’ and ‘participation’ are repeatedly name-checked in development, this has rarely resulted in change that is genuinely driven by individuals and groups with the power to influence the problem and find solutions.’

So much for domestic change agents, what about the aid agencies that pay ODI’s wages?:

‘Donors can help reform processes to adopt a problem-driven and adaptive approach, but if they are to be effective they must act as facilitators and brokers of locally led processes of change, not as managers. This means big changes in the way aid agencies work. And agencies will not change without new guidelines from the highest level: from ministers and other politicians who, in turn, respond to the perceptions and interests of voters and taxpayers. We propose, therefore, some major changes in how aid works and in the way aid is treated in public policy debates.

• Aiding development that is politically smart and locally led: Aid should do more to support initiatives that are problem-driven, adaptive and locally led. These initiatives need financial and other support that is fit for that purpose.

• An explicit refocusing of the debate on how aid works, not the total volume spent. There are many areas where spending that benefits poor countries could be increased, but the current debate about targets for aid spending is too focused on the ability of the donor country to pay, rather than whether those funds are used effectively. Looking at how aid works is more important than how much to spend.

• A new and more honest dialogue about development and aid with the public. According to recent evidence, ordinary citizens in donor countries are often irritated by simple ‘heart strings’ appeals. Many would welcome a frank discussion on how development happens, why it is often difficult and how aid can best support development that is both genuine and lasting. Efforts to support such a debate should be scaled up.’

And the interesting and new (for me at least) section on results and monitoring (and how to ensure it doesn’t go the way of Dilbert, above)

And the interesting and new (for me at least) section on results and monitoring (and how to ensure it doesn’t go the way of Dilbert, above)

‘Doing things differently should actually be more oriented towards results in two respects. First, over reasonable periods of time (which will vary according to the objective), programmes should be able to make plausible claims of having made a contribution to positive development gains, or else they should not be supported. Second, much greater efforts should be made to build up and document experience on the intermediate change processes.

Process measures of this sort could include the following.

• Measures of the extent to which issues have local salience or relevance, and whether processes give priority to local leadership and capacity. This could be based on asking simple questions about the extent to which users and local networks and organisations are involved in issue selection, design and implementation, or through perception or survey data to track how this changes over time.

• Evidence of adaptation to context. This means taking into account sub-national variance, local (formal and informal) institutions, the strength of networks, power relationships and more. This might include evidence of the use of the best knowledge available about the local political economy and its dynamics.

• Evidence of learning in action. This would measure the use of feedback loops, of evidence on past experience, and adaptation to changing conditions on the ground.

• Measures of innovation and entrepreneurial action. Sources of inspiration here may include recent attempts to monitor and measure innovation processes and impacts. Another type of test could assess the extent to which initiatives rest on a series of ‘small bets’ – i.e. spread their risk across activities – and specify the ways in which they will test and measure the effectiveness of different approaches.’

As for measuring state capability we need to ‘shift the focus of governance indicators to measures of state capacity that capture performance in core functions, rather than the adoption of particular institutional forms. Examples include the ability of a state to register all children at birth or to reduce road-traffic deaths; both of these calls for a type of state capability that could be applied to a range of development challenges. However, there is also a broader need for a better approach to identifying and measuring practical steps that can be shown to lead to improved outcomes.’

All in all a really useful contribution to building up the body of evidence and analysis underpinning the Doing Development Differently movement. But allow me one cheap shot, in relation to previous beefs about the gender blindness of much of the DDD work. The word ‘gender’ appears once in a 54 page report (in a footnote), while ‘women’ appears 5 times. In some respects, this is more same old, same old, rather than doing things differently.

And of course, as it’s ODI there are accompanying infographics etc, and this 10m video on the Philippines case study (land rights reform).

March 16, 2015

Links I Liked

A secret service version of “Where’s Waldo” in the New York Times front page photo of Obama’s recent visit to Selma [h/t Chris  Blattman and Guo Xu (@misologie)]

Blattman and Guo Xu (@misologie)]

Excellent update on evolving Piketty debates - what he got right/wrong on inequality, how he’s responded to the backlash [h/t Ricardo Fuentes]

Queuing innovation in a Thai Post Office. Wouldn’t work in UK – no-one’s going to take off their shoes, except between July and September….. [h/t  Vala Afshar and Daniel Susskind]

Vala Afshar and Daniel Susskind]

The 10 richest Africans have more wealth ($62bn) than the bottom half of its population ($59bn). The World Bank steals our best lines on inequality - and that’s a good thing (sincerest form of flattery and all that)

Not The Onion (reincarnation edition)

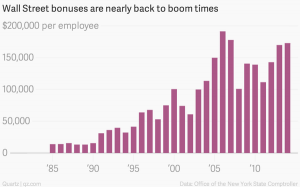

Nothing can kill the Wall St bonus [h/t Chris Blattman]

Ending Child Marriage in Chad (where more girls die in childbirth than go to secondary school). A sharp, classy UNICEF campaign video

March 13, 2015

Can greater transparency help people hold big corporations to account? Some new tools that may help

My former boss Phil Bloomer seems to be having fun in his new role running the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Here BHRRC researcher  Eniko Horvath profiles 2 new interactive platforms on company virtues/vices and how they can help the struggle for corporate responsibility.

Eniko Horvath profiles 2 new interactive platforms on company virtues/vices and how they can help the struggle for corporate responsibility.

In Mexico, the Federal Electricity Commission sued activist Bettina Cruz, for her peaceful advocacy on the social and environmental impacts of wind farms. Last month she was acquitted, but only after several years of harassment through the courts. She says the judicial system is being used to intimidate and stop the work of human rights defenders.

In Thailand, Natural Fruit brought several lawsuits against British citizen Andy Hall after he exposed alleged forced labour at its factories. Many Thai activists face similar lawsuits.

These are just two examples of the implications of the power imbalance between civil society and economic interests. In June 2011, the UN Human Rights Council endorsed a set of Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights that clarify the duties and responsibilities of States and businesses to protect, respect, and guarantee remedy for corporate human rights abuses.

Yet, space for meaningful discussions and constructive debate around companies’ human rights impacts is at risk in many places around the world.

Increased transparency of company and government actions can serve as a powerful tool to restore this imbalance. Business & Human Rights Resource Centre has recently launched two new interactive platforms that reveal company and government actions and lack thereof. Here are three ways in which transparency can empower civil society, and lead to real improvements in corporate accountability:

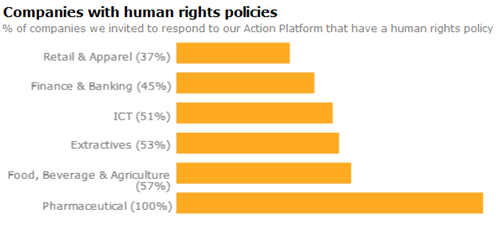

Strengthen evidence: Whether there has been “adequate” progress on business and human rights since the UN Guiding Principles were endorsed can lead to heated debates. Over 600 civil society groups have joined some governments in calling for a binding treaty on business and human rights. With the first meeting of an intergovernmental working group tasked with drafting this treaty coming up mid-2015, civil society can now point to concrete evidence of the progress that has been made, and where gaps remain. The platforms we launched are based on information provided by 94 companies and 41 governments about actions they have taken to enhance human rights protections – many provided information specifically on their implementation of the UN Guiding Principles in their responses, providing rich material for analysis.

Bolster advocacy: Transparency exposes actors that are falling short in their engagement with business and human rights. The platforms profile 87 companies and 60 governments that failed to provide respond to requests for information, at all. Importantly, most of these companies and governments also do not communicate about their practices publicly elsewhere. For example, key economic players including Canada, China, India and Russia are among governments that provide little public information on actions to improve business respect for human rights and remedy for abuses. Companies in these countries have also remained similarly quiet. This public illustration of their silence is an opportunity for civil society to engage the international community – from investors to diplomats – in giving them a wake-up call that they are lagging behind.

Transparency is also an opportunity to reward governments and companies that are leaders in the field and to highlight opportunities for improvement for others. The interactive databases give civil society the opportunity to compare actions by region or issue, and arm them with specific examples of good practices that they can hold up to their governments as they advocate for further action. Some specific examples are highlighted in this briefing.

41% of governments provided information for our Action Platforms. Some key players remained silent.

Inspire research: By revealing current practices, the platforms expose gaps where further research and guidance may be needed. For example, practices around holding companies accountable in home countries for abuses committed abroad is an area in which few governments are engaged, suggesting a rich topic for research. Furthermore, the misalignment between governments pointing to economic interests as impediments to action while companies cite a lack of political will, also suggests that there is a need for research around better coordination between business and government to drive change in a collaborative way.

Information is power. But only for those to whom it is accessible. Transparency can extend this power to citizens and civil society around the world, helping them to hold their governments and companies to account for abuses. Although there is a long way to go, transparency is the first step to driving meaningful change for people affected on the ground.

March 12, 2015

Four years into the Syrian conflict, we must never lose sight of the civilians behind the ‘story’

As the conflict in Syria enters its fifth year, Oxfam’s Head of Humanitarian Policy and Campaigns, Maya Mailer, reflects on a recent trip to Lebanon and Jordan, where she spoke with Syrian refugees, and asks whether we have become immune to the suffering of Syrians.

where she spoke with Syrian refugees, and asks whether we have become immune to the suffering of Syrians.

If you type ‘Syria’ into Google News, the headlines that normally appear are about airstrikes, beheadings, and Jihadi John. The less dramatic, everyday human cost of those caught up in the crisis gets much less play. Perhaps this is inevitable. As the conflict enters its fifth year, a sense of fatigue and helplessness has set in. My hardnosed media colleagues tell me that we need to find something ‘new’ to say. Everyday human suffering, even of such magnitude, clearly doesn’t cut it. But while international interest is waning, the suffering continues – on an epic scale.

As 21 humanitarian and human rights organisations, including Oxfam, document in a report launched today, Failing Syria, Syrians are experiencing ever-increasing levels of death and destruction. Civilians continue to be indiscriminately attacked, despite the passage in February 2014 of what was thought to be a landmark UN Security Council Resolution demanding an end to such attacks. In fact, 2014 was the deadliest year of the conflict, with reports of at least 76,000 people killed. So much for grand demands from the great powers that sit on the UN Security Council.

Noor, a Syrian refugee in Lebanon, decided to turn her tent into a school. Credit: Oriol Andres Gallart / Oxfam

In what was a middle-income country, 11.6 million people are in need of clean water. Some 3.7 million are refugees. What I try to hang on to, and I admit it’s not always easy, is that behind these colossal numbers are millions of individual lives that have been shattered. These are farmers, teachers, students, musicians – ordinary people like you and me – fighting for survival and battling for normality. People like Ayham, a pianist who performs concerts broadcast by skype amid the ruined streets of Yarmouk, a district of Damascus, or Noor, a refugee, who teaches children Arabic in a tent in Lebanon (watch Noor here).

Like many of Syria’s refugees, Noor lives in an informal settlement. The aid jargon does not do justice to what an ‘informal settlement’ is really like – a dirty area packed with people living under tarpaulins where people try their best to make a semblance of home in the midst of hardship. On a visit to one such settlement, where Oxfam is providing water, blankets and cash assistance, I sat with a refugee family in their tent, huddled around a central stove for warmth. It was home to eight people – the children, wearing flip flops in the bitter cold, charged in and out as we spoke.

The father of the family said he was increasingly anxious

A Syrian woman watches workers build Oxfam latrines in an informal settlement in Lebanon’s Northern Bekaa. Credit: Oriol Andres Gallart / Oxfam

about their legal status in the country but quickly ruled out any hope of returning to Syria soon. ‘Maybe in five or ten years – who knows?’ This became a recurring theme of the trip: on the one hand, a return to Syria was considered out of the question, but on the other, increasing restrictions on refugees was leading to acute anxiety about what tomorrow would bring in the host country.

I was struck by the impossible choices refugees were facing. With the majority living outside formal camps like Zaatari in Jordan, many refugees must pay rent to private landlords. Indeed one landowner in northern Lebanon referred to the informal settlement on his land as a ‘hotel’. But in Jordan and Lebanon, refugees face huge barriers to gaining permission to work. So where does the money come from? Cash assistance provided by agencies like Oxfam helps – and is just one example of why it is so crucial that humanitarian funding is maintained – but it’s not enough to cover the needs.

Wealthier refugees can sell off their assets, but for how long? An elderly woman told me how she had taken off her earrings and sold them, and now there was nothing left. As always, though, it is those that were poorest to begin with, who are forced to take the gravest risks. A group of women told me that ‘when it comes to the end of the month and it’s time to pay rent, some of us are very vulnerable’. Behind that word ‘vulnerable’ lay many decisions too painful for them to speak about.

Refugees also told me that some people are crossing back into Syria to bring back relatives or retrieve belongings, but are not always allowed to re-enter, leading to yet more separated families.

It’s not surprising that Syria’s neighbours are imposing border restrictions or are reluctant for refugees to work. These countries have shown incredible hospitality in hosting well over 3 million refugees, but that generosity is being tested to its limit and has huge domestic consequences. Lebanon is the most striking example. A tiny country, half the size of Wales, still recovering from a bitter 15-year civil war and where politics is carefully calibrated along confessional lines, now has the highest per capita refugee population in the world.

Omar (not his real name), 13, from Daraa in Syria, flies a kite in Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp. “Every time I fly my kite, I feel free,” he says. Credit: Pablo Tosco / Oxfam

But as the conflict rages in Syria, it is vital that borders stay open so that people can seek sanctuary. It is equally vital that the obligation of hosting refugees is shared across the globe. Some of the refugees I spoke to said resettlement was their last remaining hope. One man showed us a scrap of paper for which he’d paid $500 – a huge sum – purporting to be an official document from what was clearly a fictitious consulate. Others told us that they were saving up to get on a boat to cross the Mediterranean or had relatives who had already tried to do so – and drowned.

The UK, which has so far resettled only about 143 refugees from the region as well as offering asylum to some 4000 refugees who were already in the country, has variously argued that resettlement is too expensive, not a sustainable solution for such a huge refugee population, and that it is best to support refugees in the region. While this may be true and the UK should be commended for its leading aid effort, it should not shirk its responsibility on resettlement. It should offer a lifeline to many more of the most vulnerable refugee men, women and children.

Oxfam together with the British Refugee Council, Amnesty International, Save the Children and others have called on rich countries to take five per cent of the total refugee population, which in the UK would equate to offering resettlement to around 10,000 refugees from Syria (see report here and a celebrity letter to Cameron here).

Ultimately, of course, a political solution is needed. I spoke recently to a Syrian peace activist who said that Syria was still waiting for its ‘Rwanda moment’. By that, he meant that there needed to be a groundswell of global moral outrage so great that it would be impossible for the world to ignore what was happening and do all it can to stop it.

To be honest, I’ve been struggling with this, as surely that moment has long gone. If the death of over 200,000 people including thousands of children isn’t enough, then what is? But giving up isn’t an option for Syrians and it’s not an option for us either. We must continue to shine a spotlight on Syria and build the political resolve to end the bloodshed (you can take action here).

the report comes with a powerful new 90 second video

March 11, 2015

Blueprint for Revolution, a fantastically readable and useful handbook for activists

This review also went up on the Guardian Development Professionals Network site

I recently summarized a New York Times piece on non-violent activism, discussing the ideas of the Serbian protestors who overthrew Slobodan Milosevic , and then went on to train protest movements around the world. I’ve now read the new book by one of the leaders, Srjdja Popovic (right), and it’s brilliant. First prize for readability (and length of title – the full version is ‘Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men and other Non-Violent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators or Simply Change the World’).

, and then went on to train protest movements around the world. I’ve now read the new book by one of the leaders, Srjdja Popovic (right), and it’s brilliant. First prize for readability (and length of title – the full version is ‘Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men and other Non-Violent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators or Simply Change the World’).

Popovic describes his ‘personal journey from a too-cool-to-care Belgrade guitarist to one of the leaders of Otpor!, the nonviolent movement that toppled the Serbian dictator’, and the style is anything but worthy: wonderfully contemporary-European, full of knowing cultural references, witty asides and awareness of the reader. A really fun (and funny) read (and you can’t say that for many politics books).

His twin sources of inspiration are Tolkien – ‘If I had to choose one book to call my scripture, it would be Lord of the Rings’ (activists are hobbits, ordinary folk allying with a motley collection of unusual suspects – dwarves, elves etc – to take down the Dark Lord) and Monty Python (dictators can’t handle humour, and it makes being an activist fun). His other less eccentric inspiration is non-violence guru Gene Sharp.

Blueprint for Revolution echoes a lot of the advocacy techniques I talk about on this blog (albeit in much more engaging language) – power analysis, quick wins, clear narratives, identify champions, allies, blockers and the undecided.

Although it’s called a blueprint, he respects national roots and difference, building his case on his huge collection of experiences from Serbia, and his subsequent career with CANVAS, training activists in some of the hottest political struggles around (Burma, Syria, Egypt).

Although it’s called a blueprint, he respects national roots and difference, building his case on his huge collection of experiences from Serbia, and his subsequent career with CANVAS, training activists in some of the hottest political struggles around (Burma, Syria, Egypt).

Some of the book’s big themes include:

Branding really matters – ‘we wanted Serbs to have a visual image they could associate with our movement [so they went for a clenched fist – cheesy, but effective, and it echoed Partisan heroes of WW2]. Struggle becomes a battle of the brands because ‘Every dictator is a brand’ (this is Gramsci for the 21st C). ‘We need a brand that is better than theirs.’

Dream big (a compelling and positive ‘vision of tomorrow’) but start small. Find tactics that will prove ‘we are the many and they are the few’, without getting you ‘killed or roughed up too badly’, like taxi go-slows in Pinochet’s Chile; or mildly subversive ringtones in Iran.

Food is one of the best entry points. Activists have built movements around cottage cheese (Israel), rice pudding (Maldives) and most famously, salt (Gandhi) and tea (US). ‘Food has a special way of getting people to come together’, and is often low risk – it gets the ball rolling. But there are other small starters too – Harvey Milk’s political career took off when he switched from gay rights to campaigning against dog shit in San Francisco’s parks, recognizing ‘this very important principle of non-violent activism: namely that people, without exception and without fail, just don’t give a damn.’ The trick is really listening and finding out what other people care about, even if it’s not top of your priority list. The alternative is ‘rally the people who already more or less believe in what you have to say. That is a great way for coming tenth at anything’ (as Harvey Milk initially did).

Practice laughtivism (he admits it’s a terrible word, but quotes Mark Twain ‘the human race has unquestionably one really effective weapon – laughter…. Against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand.’). ‘In the age of the internet and other distractions, laughter was our greatest weapon.’ Popovic’s crew released anti-regime accessorised turkeys onto the streets of Belgrade (you had to be there), while Syrian protestors buried loudspeakers broadcasting anti-regime messages in smelly dustbins in Aleppo (so the police made themselves look ridiculous, and less scary, rummaging around to find them).

I think we’ve lost the power of humour in some of our more finger-wagging activism. That is serious because ‘Humour breaks fear and builds confidence.

Just add salt

It also adds the necessary cool factor, which helps movements attract new members. Finally, humour can incite clumsy reactions from your opponents – the high and mighty can’t take a joke.’

Be cool (not usually an NGO strong point, though the grassroots protestors are cooler). In Serbia, getting arrested turned you into an instant sex magnet, especially if you earned the black Otpor! T shirt awarded only to those arrested 10 times or more.

Stick firmly to non-violence because it works – ‘if you’re up against David Beckham, you don’t want to meet him on the soccer field. You want to play him at chess. Taking up arms against a dictator is silly.’ ‘Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict’ by Erica Chenoweth and Maria J Stephan, identified 323 conflicts from 1900-2006. They found ‘nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts’ (53% against 26%).

But make them oppress you. ‘Making oppression backfire is a skill every activist can and must master – like jujitsu, it’s all about playing your opponents’ strongest card against them.’ In Serbia Otpor! turned arrests into events, with elaborate pre-arranged systems for notifying parents and colleagues of arrests, crowds outside the prisons singing pop songs and chanting the prisoners’ names, and ‘rock star receptions’ (and T shirts) when people were released.

Invest everything in building and maintaining unity (of message as well as organizations and alliances).

Know how to win: declare victory too early and it all unravels (Egypt), stay maximalist and you lose the chance of quick wins and building momentum (Tiananmen Square). Be clear on what your aim is (democracy rather than the fall of Mubarak). Keep unity after victory rather than return to infighting (Ukraine). ‘Successful movements must have the patience to keep working hard even when the lights and cameras have moved on.’

And that last para points to one of the strengths of the book: Popovic is willing to criticise where he thinks movements have got it wrong – the Russian protest movement for sticking to largely middle class concerns and failing to build bridges; Tiananmen square students for failing to accept and loudly celebrate early offers of climbdowns (as Gandhi did) and instead demanding ‘everything or nothing’ – they got the latter. What would Gandhi have done in Tiananmen Square? He thinks Occupy is a really badly chosen name, as it describes a tactic, not a strategy or vision – what would have happened if they had called themselves ‘the 99 per cent’?

One whinge – he has an alarming tendency to overclaim on Otpor!/CANVAS’ impact – Burma’s saffron revolution is apparently all down to someone smuggling an Otpor! DVD into a Burmese monastery. Some Egyptian activists come to a training session and voila, Tahrir Square! Yeah, right.

That aside, it is a wonderful book – make sure you give it to your friends after you’ve read it.

March 10, 2015

What to do about Inequality, Shrinking Wages and the perils of PPPs? A conversation with Kaushik Basu, World Bank chief economist

Along with a bunch of policy wonks from NGOs and thinktanks, I had an exchange with World Bank chief economist Kaushik Basu this week. Rules of  engagement were that the meeting was off the record, but I was allowed to blog as long as the Bank saw a draft to make sure I wasn’t about to get him the sack. In the end, however, the Bank asked for only one minor change to my first draft (clarifying his views on PPPs).

engagement were that the meeting was off the record, but I was allowed to blog as long as the Bank saw a draft to make sure I wasn’t about to get him the sack. In the end, however, the Bank asked for only one minor change to my first draft (clarifying his views on PPPs).

Kaushik had a similar session with us back in 2012, soon after he took up his position, and this time both echoed similar themes (e.g. a very Indian take on the basic right to food), and added some new ones. He brings an Indian sensibility to the job – strong on rights, the lives of poor people, and a scepticism about the inefficiencies of state provision (eg India’s Public Distribution System for basic foodstuffs), plus a fascination with IT and the role of the private sector. His predecessor, Justin Lin, had a more Chinese take, stressing industrial policy. Both have provided valuable counterpoints to the anglosaxon individualism of traditional Bank economics.

From my point of view the most striking discussions were on inequality, labour and Public Private Partnerships.

On inequality, Kaushik acknowledged that the topic has become much more prominent in debates over the last two years, partly due to Pikettymania. ‘Post Piketty, there has been a lot of discussion on whether Inequality is getting worse or not. For me, that part of debate is not that important, because Inequality is already too great.’

He is particularly exercised (‘A great injustice’) by inequality at birth (‘you really can’t justify it by saying babies are either hard working or lazy!’). He is trying to develop an at-birth gini coefficient, which could be interesting. But he is fairly timid on what to do about it – the standard Bank recipes of improved healthcare and education (although he insists they should be free at the point of use) and a ‘little less inequality at the start of life, where taxation can play a little bit of a role’.’An Inheritance tax makes sense – it’s a plain notion of justice. That is one kind of taxation I can get behind.’

What about the guys on the bus?

Around the time Kaushik joined the Bank, it adopted a ‘shared prosperity’ goal, to ‘increase per capita real household income or consumption of the bottom 40 percent of each country’s population’. Critics, including Oxfam, were pretty underwhelmed by this as it seemed to dodge issues of extreme wealth concentration (and political capture) by elites. Kaushik defended it, though, partly arguing that it was as far as the Bank could go on this issue, but also pointing out that it’s pretty easy to work out from the growth figures for the bottom 40% and the economy as a whole, whether poor people’s slice of the pie is growing or note, and arguing that the great virtue of the goal is that (unlike absolute poverty targets of $X per day) it applies to rich and poor countries alike.

I would argue that given how inequality has now become a mainstream topic, the Bank ought now to be able to make a sharper comparison with the incomes of the top 1 or even 0.1% , which is perhaps the most important story on inequality right now. But Kaushik didn’t answer my question on inequality leading to political capture – maybe that’s just too politically tricky for the Bank to address. However he did acknowledge that the Bank has ‘been a bit slow’ in identifying and promoting policies to address inequality (as Nora Lustig is doing, for example). On gender inequality, he wants to make the Bank’s biannual ‘Women, Business and the Law’ report much higher profile – it covers issues like access to finance.

On labour, he said ‘The declining share of labour’s income does worry me. Multiple crises over the last 7-8 years have at their base a tectonic shift in the structure of global market. The regulation v deregulation argument doesn’t tackle that problem. The real challenge is that you can’t stop the march of machinery that is a) displacing labour and b) linking up labour in distant lands’ (which is a good thing). He argues that we have to identify other ‘pools of cash’ (taxation, natural resource revenues) and use them as compensation for the declining share of wages, both because it is the right thing to do, and in order to prevent social and political disorder.

On Public Private Partnerships, he stressed his desire to increase private sector involvement in helping developing countries progress, but said this was  not at all the same thing as uncritical support for PPPs. ‘The way PPPs are done worries me a lot. These are two very different creatures being brought together in a single cage and one can just gobble up the other. The private sector is often much smarter at writing the contracts, so the taxpayer carries the can when bankruptcy occurs. We have to be acutely aware of this – I have heard many private sector companies say there is nothing as good as a deal with the public sector!’

not at all the same thing as uncritical support for PPPs. ‘The way PPPs are done worries me a lot. These are two very different creatures being brought together in a single cage and one can just gobble up the other. The private sector is often much smarter at writing the contracts, so the taxpayer carries the can when bankruptcy occurs. We have to be acutely aware of this – I have heard many private sector companies say there is nothing as good as a deal with the public sector!’

But Kaushik believes that while PPPs done in a cavalier fashion can do damage, that is no reason to abandon them. Instead, donors have to work hard to design the contracts better to make sure that the risks and burdens are shared equitably between the two Ps of the PPPs.

I hope the Bank is listening, because despite the evidence of their flaws in areas such as health or agriculture, PPPs are very expensive and seem to be ‘gobbling up’ an increasing slice of its cash right now (and where the Bank leads, other donors tend to follow).

March 9, 2015

Links I Liked

12 leading reporters on aid and development – one for your RSS/twitter feed

‘Frequent email checks temporarily lower your intelligence more than being stoned.’ Brilliant tips on how to be (more) efficient

227 studies later, what actually works to improve learning in developing countries? Teacher training, accountability and ‘Pedagogical interventions that match teaching to individual student learning levels’, apparently

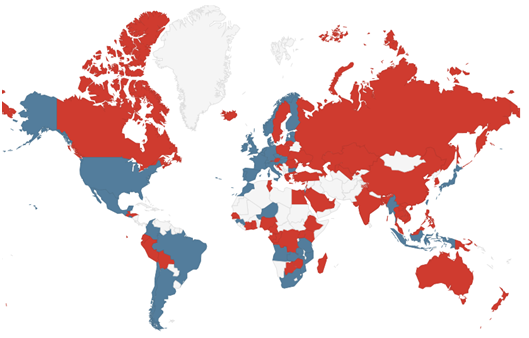

Should society accept homosexuality? 2013 poll [h/t Conrad Hackett]

Should society accept homosexuality? 2013 poll [h/t Conrad Hackett]

88% yes – Spain

80% Canada

60% US

9% Turkey

Improving health systems in Ebola nations would have helped prevent it at one third of the cost of the relief effort, according to a new Save the Kids report

For the first time, more people in the developing world now die from strokes and heart attacks than infectious diseases. Time to launch OxFat?

One man and his rat – strangely touching. ‘Heroic’ giant rats sniff out landmines in Tanzania – and when they say giant, they’re not joking

March 5, 2015

The global women’s rights movement: what others can learn, a progress stocktake and some great videos for IWD

It’s International Women’s Day on Sunday, which is swiftly followed by celebrations around the 20th anniversary of the 1995 Beijing conference (I still

IWD, 1975 style

remember the buzz from women returning from that) and the start of the 59th Commission on the Status of Women at the UN – an annual spotlight on progress (or otherwise) on women’s rights.

Gender is a big deal in Oxfam, and I’ve often been struck by what the rest of the development business can learn from progress on gender rights, and the activism that underpins it. For starters:

Power begins with ‘power within’, when previously marginalized people kindle their sense of rights, dignity and voice. Far more of our work should start there.

Norms really matter. Gender activism shows just how shallow a lot of advocacy can be, when it concentrates on the ephemera of policy, and ignores the social norms that underpin identity and injustice. And international movements can have real impact on those norms.

Stamina: any struggle worth its salt takes decades – you don’t just look for a quick win and move on.

The world beyond money – work on areas such as the ‘care economy’ highlights just how much of what really matters lies outside the monetary economy that dominates thinking on development. We should be talking about shame and joy as much as about income and assets.

(I also happen to think the gender activists could learn useful lessons from others, but that’s another post.)

As for IWD, first some heavy policy, then some fun videos.

The balance of achievements since Beijing and the remaining injustices is nicely summarized in a new paper from the Gender and Development Network (left):

‘Looking back over the last two decades there is a cause for celebration and frustration. Gender equality is now on the political agenda, apparent in the rhetoric around international agreements and accompanied by some new national legalisation to promote or protect women’s and girls’ rights and gender equality. There has been some progress on the ground, especially in areas which were prioritised by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) such as education, national-level political participation and maternal health. There is also an emerging evidence and practice base, particularly through the work of women’s rights organisations, providing valuable lessons for the future.

However, despite the commitments made, and a growing understanding as to what gender equality entails and the most effective ways to achieve it, progress has remained slow and

uneven. Efforts by governments and donors have largely been piecemeal, focusing on individual women and girls and on too narrowly defined manifestations of their inequality. In every country in the world, women and girls are still disproportionately represented amongst the poorest and most marginalised. They continue to face violence, discrimination, constrained economic choices and exclusion from decisions over their lives; for those in conflict-affected and humanitarian settings, the situation is even worse. One in three women worldwide experiences sexual and/or intimate partner violence.2 Every day there are almost 800 preventable deaths of women in pregnancy or childbirth. Peace negotiations take place with women almost entirely absent from the table. Women and girls continue to be disproportionately responsible for care work and are twice as likely as men to be living in extreme poverty. Where gender inequality intersects with other inequalities such as income levels, race, ethnicity, disability, caste, age, marital status and sexuality, the abuse of rights is further compounded. For example, less than half of girls with a disability complete primary school.’

The report highlights four areas where structural barriers are blocking the struggle for equality:

Building the autonomy and agency of women and girls

If women and girls are to benefit from opportunities to access more resources and exercise greater power they must have agency, which is the ability to make and act on choices and so control their own lives. Policy and programmes that work directly with marginalised women and girls to build their agency, allowing them to identify their own priorities and solutions, require a move away from perceiving women and girls as simply a ‘vulnerable group’, to active citizens who should be part of decision making processes. To successfully promote self-esteem and confidence, interventions will also need to recognise the specific needs of those women and girls facing multiple discrimination.

Supporting women’s collective action

Change occurs when women act collectively, some of the most important advances in women’s and girls’ rights have been secured through the efforts of women’s rights organisations and movements. Organisations with a primary focus on promoting women’s rights and gender equality, led by women for women, are particularly well-equipped to work with marginalised women and girls in order to enable them to build their capacity and agency, speak for themselves and take collective action.16 Yet funding for these types of organisations remains limited, and is frequently too short-term and restricted to enable the transformative programming needed.

Challenging discriminatory social norms

Discriminatory social norms – widely shared beliefs, practices and rules – legitimise and perpetuate gender inequality by normalising women’s and girls’

roles, for example as ‘carers’ and followers rather than ‘bread-winners’ and leaders. National institutions such as the police, military, education systems, and particularly the media further reinforce these norms. Occupational segregation, early and forced marriage, exclusion from decision making, responsibility for unpaid care work and the widespread acceptance of VAWG are all ways in which discriminatory social norms adversely impact on women’s and girls’ choices and chances.

Change in social norms can be measured, and should therefore be included as targets in international agreements and resourced by governments and donors as a first step. Challenging discriminatory norms requires investment in empowering women and girls to question these norms and go ‘against the grain’ in order to take more control of their own lives. It also means working with communities, particularly influential community leaders, to change what is considered acceptable.

Alternative economic policies

Commitments made at and since the Beijing conference reflect an expectation that governments are responsible for implementing policies to improve the lives of women, especially poor women. However the negative impact of neo-liberal policies on governments’ ability to do so was not addressed. The inconsistency between such commitments, and the continued pursuit of growth-focussed neo-liberal policies, has had a significant impact on progress in all areas of gender equality. Regressive taxation, cuts in public services, privatisation and deregulation have all taken their toll alongside the impact of austerity measures which fall disproportionately on women. Failure to acknowledge the importance of the care economy and women’s unpaid work has also been a major omission.’

And here are the videos. I tried to crowd source from Twitter, but the only celebratory (rather than worthy-but-dull) video came with this amazing (if entirely random/tangential to IWD) bit of Tanzanian keepy-uppy [h/t Rob Grant].

https://www.youtube.com/watch?wmode=t...” width=”WIDTH” height=”HEIGHT” >

Jose Barahona sent round this Oxfam-heavy, but nonetheless inspiring story from our work with Citizens Protection Committees in the DRC:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?wmode=t...” width=”WIDTH” height=”HEIGHT” >

But otherwise, I’m forced to fall back on some merit-based nepotism. My sister-in-law Mary Matheson (@Mary_Matheson1) makes films for Plan International and went into orbit when both Barack and Michelle Obama highlighted her award-winning animation on girls’ rights and voice this week (shame that FLOTUS invoked one of my pet bugbears, the largely meaningless ‘70% of the world’s poor are women’ ‘fact’ in her tweet, but there we go).

And then there’s Mary’s Malala video (this one always makes me cry – make sure you’ve got a hanky).

Happy IWD everyone, and do please send in your favourite videos – I can always use them next year

March 4, 2015

I’m looking for an innovative publisher for my next book (on How Change Happens) – any suggestions?

As regular FP2Pistas should have clocked by now, I am writing a book on ‘How Change Happens’. Should have a final manuscript by later this year, to

The fear

publish in 2016. But in a desperate courageous attempt to be funky and innovative, we want to do things a bit differently this time:

1. It won’t be that long – aiming for 200-250 pages compared to monster FP2P length

2. Much bigger online presence – a platform/hub/lab/whatever crammed with case studies, toolkits, videos etc will accompany the book

3. Open Access: if people really want to print out a 250 page book, they will be able to. We still think lots will opt for the traditional or e-book version, but the publisher will have to be ready to that gamble.

4. A MOOC: we’re going to do a ‘massive online open course’ to accompany the book, which should both increase impact and improve sales.

Other things will be unchanged – remorseless authorial self promotion in person and via this blog, Oxfam’s backing, a style combining literature review and loads of case studies, and a dogged effort to avoid the wilder excesses of development-speak.

We’re already talking to various publishers, but it seemed a bit remiss to not go open access on a proposal about open access…. So if you’re interested in submitting a proposal, please contact Emily Gillingham (egillingham[at]Oxfam.org.uk] for the 3 pager that sets this all out in more detail.

The Reality

March 3, 2015

What would persuade the aid business to ‘think and work politically’?

Some wonks from the ‘thinking and working politically’ (TWP) network discussed its influencing strategy last week. There were some people with proper

True that, Albert

jobs there, who demanded Chatham House Rules, which happily means I don’t have to remember who said what (or credit anyone).

The discussion was interesting because it covered ground relevant to almost anyone trying to shift an internal consensus (in this case towards aid donors taking more account of politics, power, institutions etc in their work). Some highlights:

Who are your target groups? The ‘aid industry’ or ‘governments’ is far too wide. The best effort identified four: in the rich countries, professional advisers within donors and relevant academic networks; in the developing country, politicians and senior officials.

Within those target groups, there are ‘natural allies’, who entirely understand the importance of thinking in terms of locally specific politics, incentives, institutions etc rather than checklists of best practice. Interestingly, they may not be obvious – diplomats and foreign office types ‘get’ this much more easily than their more econo-technocratic aid ministry counterparts. Sectoral specialists in health and sanitation have done a lot of thinking on systems, but (reportedly) education and water engineers less so.

The next question is ‘what persuades your targets?’ My bet would be that the most important factor is the messenger, not the message – if a senior politician hears about TWP thinking from their university professor, or a retired political heavyweight, they are far more likely to listen. So perhaps we should deliberately recruit a lot of ‘old men in a hurry’ – apologies for gender bias there, Mary Robinson and Graca Machel are great counterexamples – retired big cheeses keen to make a difference.

The next question is ‘what persuades your targets?’ My bet would be that the most important factor is the messenger, not the message – if a senior politician hears about TWP thinking from their university professor, or a retired political heavyweight, they are far more likely to listen. So perhaps we should deliberately recruit a lot of ‘old men in a hurry’ – apologies for gender bias there, Mary Robinson and Graca Machel are great counterexamples – retired big cheeses keen to make a difference.

Incentives can get in the way here, in that the institutional make-up of TWP means people have hammers, and so are usually looking for nails. Researchers want things to research and have an overwhelming urge to split hairs and generally complicate everything; consultants want to develop products and toolkits and generally make themselves indispensable. Both usually feel the need to begin by trashing their rivals, even if what they are saying is almost indiscernibly different. Both can only do things if they are funded by someone (typically an aid donor).

But what if influencing the targets means creating a major sense of risk and the need for change by highlighting (preferably in the Daily Mail) the failures of those same aid agencies? Dropping everything to lobby like hell when a new minister takes over, creating a brief window of opportunity? Repeating a simple message endlessly and avoiding too much nuance? Setting up mentoring and programme exchanges with successful examples on the ground?

There are several quagmires around the use of the word ‘politics’. The word puts off people who may actually be ‘thinking politically’, but talk in terms of education, health etc – and it can easily come across as a turf grab by governance people. To targets in developing countries, it can sound like political interference by donors (and let’s be honest, to some extent it is!). But on the other hand, how can we talk about politics by downplaying politics?

In addition, lots of people in the aid business (and especially in the diplomatic corps!) think they are already ‘working politically’. So urging them to do so is more likely to alienate than persuade (see recent rant on annoying your target audience), unless we can show very clearly (and quickly) what they would need to do differently in a TWP approach.

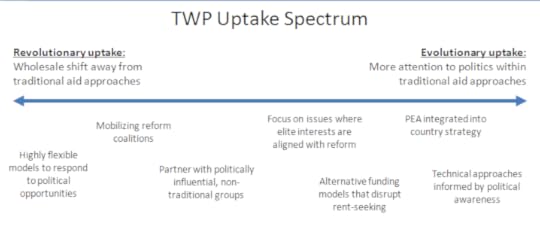

There are some bigger questions about the purpose of TWP: is it primarily about ‘small p’ politics – using political economy analysis to design better aid programmes with a greater chance of success. Or is it about Big P – empowerment, transformation, shaking everything up, redistributing power etc? At the moment it is rather fudging the issue (see graphic), and I think at some point it will have to decide.

There are some bigger questions about the purpose of TWP: is it primarily about ‘small p’ politics – using political economy analysis to design better aid programmes with a greater chance of success. Or is it about Big P – empowerment, transformation, shaking everything up, redistributing power etc? At the moment it is rather fudging the issue (see graphic), and I think at some point it will have to decide.

Putting those last two paras together makes me think TWP should probably accept its institutional constraints and go for small P. How about ‘Politics is  Value for Money’ as a slogan? (only half-joking)

Value for Money’ as a slogan? (only half-joking)

My suggested basic messages for Politics as VFM:

The current system doesn’t work: here are 5 disasters from ignoring politics

We have new ideas that work and we can prove it

Here are some key (

And some FAQs and Myth busters

What do we mean by ‘working politically’?

Is this just about governance?

So you think you’re doing it already? Ask yourself these questions…….

Why this is not (just) about governance

Any additional suggestions very welcome!

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers