Duncan Green's Blog, page 168

March 30, 2015

A Novel Idea: Would Fiction be a better induction to a new job than boring briefings?

A mysterious, anonymised, scarlet pimpernel character called J. flits around the aid world, writing a blog (Tales from the Hood – now defunct, but collected into a book, Letters Left Unsent) and fiction. He asked me for a plug for the latest novel, Honor Among Thieves.

Among Thieves.

Here’s the plot blurb:

‘Mary-Anne has left East Africa and traded in her dusty cargo pants for business suits at the World Aid Corps (WAC) headquarters in Washington, D.C. Her first major assignment, planning a new corporate-funded project in a rural village in Cambodia, seems simple enough—at first. Before long, she is caught in a web of high-stakes aid world maneuvering, board room deals, conflicting priorities, and hidden agendas that threatens not only to destroy her career, but rob her of her soul.

From the iridescent rice fields of the Mekong Delta, to the curiously named bars and teeming backstreets of Phnom Penh, Mary-Anne finds her journey inextricably tied to others: a bereaved Cambodian mother, an arrogant colleague with something to prove, and a demanding donor with something to gain. As she searches for the sweet spot between humanitarian idealism and donors’ expectations, will she be able to do what she knows in her heart is right? Whose version of “helping” really helps? And who are the real humanitarians?’

It’s not Graham Greene, but it’s a good read: I recognized the characters and dilemmas it painted, the arc from wet behind the ears volunteer to world-weary manager, and the distinctive aid worker cocktail of mission and daily grind, cynicism and zeal. There are plenty of intersecting subplots to keep you entertained: newbie Trevor starts a new NGO without a clue what to do, and promptly gets Chlamydia; aging Cambodia hand Frank tries to run a bar without ‘massage’ on the menu; villager Phirun is in hock to a moneylender who takes his wife to work in the fleshpots of Phnom Penh.

But it also makes few concessions to a non aid audience – a fair sprinkling of jargon, acronyms etc, many of them unexplained. At first I tutted, but then thought – this could be a whole new genre. Vocational novels, providing a painless introduction to any given career and its jargon, not just aid: accountancy? Lawyers? (actually, they’re pretty well covered); quantity surveyors?

I think J may be onto something here. I’m thinking about a novel on political economy analysis and theories of change – what do you reckon?

As for J. himself, we know he’s a he from the blurb he sent round with the manuscript

‘J. has worked in the humanitarian aid industry since 1991. Since then he’s been involved in the response to most of the major humanitarian crises you’d have heard of, as well as many that you might not have heard of. He presently holds a real aid job with a global aid organization. He writes about humanitarian aid, both fiction and non-fiction, in his spare time, with a personal computer, because he enjoys it.’

A good airplane read – check it out.

March 29, 2015

Links I Liked

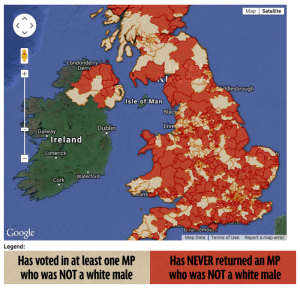

The campaign for the 7 May UK election is heating up folks: The areas in red have only ever had white male MPs [h/t Federica Cocco]

Cocco]

Global Justice Now’s #FreeTheSeeds campaign: Are outsiders imposing disastrous noble-savageism, or defending Africa’s food security?

Can religious groups help to prevent violent conflict? Nice examples from Nigeria, DRC,

Most desired jobs in Britain: Author 60% Academic 51% Investment Banker 26% [/h/t Conrad Hackett]

Time to move on from income inequality and the Gini index. We need new ways to measure different kinds of inequality

And now for some Videos I’d Vote for

Winner of WaterAid/ WorldView’s SH2Orts competition. Walking to the moon (16 times) to fetch water. A film by Sven Harding

An Indian superman carries a motorbike on his head. Up a ladder. And no-one even comments. [h/t Richard Cunliffe]

Total gotcha TV: Pesticide lobbyist Patrick Moore says glyphosate weedkiller is so safe people can drink it, but then is offered some to drink on camera. ‘I’d be happy to. Not really. I’m not stupid’.

March 27, 2015

1/4 of the world’s people already subject to large annual wealth tax to tackle poverty. Has anyone told Piketty?

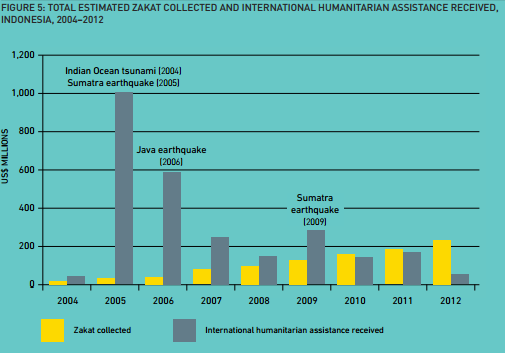

A few years ago, I sat next to a young muslim guy from Birmingham on a plane, and he told me how frustrated he was with the  way his community’s annual act of alms-giving, known as Zakat, was managed – no accountability, no real checks on where it goes or what it achieves. I’ve wondered about that ever since, so yesterday I went online to watch the launch of An Act of Faith: Humanitarian Financing and Zakat, a new report by the Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) programme. The report is excellent. Here’s my summary and a few comments:

way his community’s annual act of alms-giving, known as Zakat, was managed – no accountability, no real checks on where it goes or what it achieves. I’ve wondered about that ever since, so yesterday I went online to watch the launch of An Act of Faith: Humanitarian Financing and Zakat, a new report by the Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) programme. The report is excellent. Here’s my summary and a few comments:

What is Zakat?

All of the world’s major religions contain some element of almsgiving, but Zakat is different because it is mandatory for all Muslims who are able to pay it, and is one of the five pillars of Islam. The word Zakat can be translated to mean ‘purification’ or ‘growth’. Through Zakat, Muslims are required to give a proportion – traditionally defined as one-fortieth, or 2.5% – of their accumulated wealth for the benefit of the poor or needy (and other recipients as highlighted in the verse of the Qur’an, below).

“Alms are for the poor and the needy, and those employed to administer the (funds); for those whose hearts have been (recently) reconciled (To Truth); for those in bondage and in debt; in the cause of God; and for the wayfarer.” (Qur’an 9:60)

Has anyone told Thomas Piketty and the inequality campaigners that we already have a global wealth tax in place. And rather a large one, affecting one in four of the world’s people?

Donations overtake receipts in Indonesia

What are the Numbers?

The short answer is we don’t know, but it’s a lot of cash. The paper cites previous global estimates of anywhere between US$200 billion and US$1 trillion a year. A speaker at the launch (couldn’t find the names on the webpage, sorry) pointed out that 2.5% of the combined GDP of the Middle East and North Africa comes to $65bn a year.

According to the report: ‘Data we have collected for Indonesia, Malaysia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, which make up 17% of the world’s estimated Muslim population, indicates that in these countries alone at least US$5.7 billion is currently collected in Zakat each year.

We estimate that the global volume of Zakat collected each year through formal mechanisms is, at the very least, in the tens of billions of dollars. If we also consider Zakat paid through informal mechanisms, then the actual amount could be in the hundreds of billions of dollars.’

Zakat and Humanitarian Response

Islamic countries are central to humanitarian response both as recipients and (increasingly) as donors. Between 2011 and 2013, international humanitarian assistance from governments within the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) grew from US$599 million to over US$2.2 billion, a growth in the share of total international humanitarian assistance from governments from 4% to 14%. A speaker at the launch claimed that Turkey is now the world’s third largest humanitarian donor (Syria, Somalia). At the same time, an estimated 75% of people living in the top ten recipient countries of humanitarian assistance in 2013 were Muslim.

The report found that ‘between 23% and 57% of Zakat currently collected is used for humanitarian assistance, depending on the context in which it is raised and used…. the amount of Zakat potentially available in both Indonesia and Pakistan could meet all current requirements to respond to domestic humanitarian emergencies, with significant amounts remaining to cover other areas of Zakat spending.’

How is Zakat collected?

Government-collected: Zakat In Islamic and Muslim-majority countries is collected and distributed by the state. Six  countries have legally enforced payments of the Zakat; for three of these, the responsibility of the state for collecting Zakat appears in the national constitution.

countries have legally enforced payments of the Zakat; for three of these, the responsibility of the state for collecting Zakat appears in the national constitution.

Independent collection and delivery agencies: In some Islamic and Muslim-majority countries, the government oversees the collection and distribution of Zakat, but independent agencies are given a license to manage the process. This is the case in Malaysia, for example, where individuals can choose which approved agency they pay their Zakat to.

In countries where Zakat is not managed by the state and there is no governing body overseeing collection and distribution, Muslim citizens can choose how to pay their Zakat and to whom. Many Muslims living in Muslim-minority and/or non-Islamic countries choose to pay their Zakat to charities or other NGOs, which use the money to fund their own programmes.

Mosques: Mosques collect large sums of Zakat, particularly in non-Muslim countries with no centralised or government-managed Zakat collection agency. Zakat collected by mosques may be spent on the mosque itself – such as on upkeep or renovations – or it may be distributed by the mosque to local people in need. Some may also be passed onto a third-party organisation, such as an Islamic charity or international NGO.

Individuals: Some Muslims believe that Zakat should not be paid via a third party; rather that it should be a direct transaction between the person giving (the muzakki) and the person receiving it (the mustahiq). Many people therefore give their Zakat directly, perhaps to someone in need who lives within their community, or to someone further afield with whom they have connections. In this way, funds given through Zakat may contribute to money sent abroad in the form of remittances.

Could Zakat provide big new flows of money for humanitarian response?

Potentially. However, ‘there are a number of possible barriers that will need to be overcome if Zakat is to fully realise its humanitarian potential’. According to the report, ‘These fall into two main categories:

• Logistical – such as streamlining and formalising how Zakat is collected, by whom, and how it is channelled to the humanitarian response community.

• Ideological – such as how best to manage conflicting opinions on whether non-Muslims can benefit from Zakat and where it can be used. The question of whether non-Muslims can benefit from Zakat is central to discussions concerning the compatibility of Zakat with humanitarian principles.

To begin to address these barriers, interested parties need to focus efforts in five areas:

1) Humanitarian donors and agencies should engage in discussion with academics, Islamic scholars, theologians and practitioners, and share learning on the use of Zakat for humanitarian assistance.

2) An independent and credible global body that has taken part in these discussions needs to provide guidance on the parameters of reasonable interpretations of Zakat.

3) Actors at all levels – including small, local Zakat-receiving organisations, national and international NGOs, and the UN should work together to improve channels between Zakat funds given and the international humanitarian response system.

4) Resource-mobilisation efforts should focus on increasing Zakat revenues and channelling new funds to humanitarian assistance, rather than redirecting existing funds.

5) Efforts to increase the use of Zakat for humanitarian assistance should be combined with those of the wider development community to ensure a complementary approach.’

The main additional points that came across on an intermittent webstream from the launch were:

a) serious problems in internationalizing flows of Zakat, due to the proliferation of counter-terrorism and money laundering controls on flows such to countries like Somalia

b) huge suspicion both of governments and international organizations (bureaucracy, theft), leading to a call for an organization such as the Islamic Development Bank to set up some kind of Zakat International (apparently they are doing some initial thinking about it). Some thought the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul would provide the perfect launchpad for some kind of initiative.

c) Insistence that this should be a two way process. Not just about how to hoover up Zakat to fund a western-designed humanitarian system, but also about what that system can learn from Islam.

What did I miss?

March 26, 2015

Where have we got to on ‘results-based aid’, ‘cash on delivery’ etc?

The Center for Global Development churns out any number of new ideas and energetically hawks them round northern  governments and multilaterals: the benefits of migration, oil for cash, the Commitment to Development Index and many more (check out the Initiatives tab on their homepage). In recent years, Cash on Delivery aid has been one of their top products, and a number of donors have started to pick up the idea (although just to keep us on our toes, its name keeps changing – to ‘Results-Based Aid’, or ‘Payment by Results’. Apparently this is because what’s happening so far doesn’t meet the full set of COD criteria set out in CGD’s book).

governments and multilaterals: the benefits of migration, oil for cash, the Commitment to Development Index and many more (check out the Initiatives tab on their homepage). In recent years, Cash on Delivery aid has been one of their top products, and a number of donors have started to pick up the idea (although just to keep us on our toes, its name keeps changing – to ‘Results-Based Aid’, or ‘Payment by Results’. Apparently this is because what’s happening so far doesn’t meet the full set of COD criteria set out in CGD’s book).

According to the CGD, ‘Under COD Aid, donors would pay for measurable and verifiable progress on specific outcomes, such as $100 dollars for every child above baseline expectations who completes primary school and takes a test.’

The appeal of this approach is that it leaves governments and other recipients to find their own way to achieve good things, based on local contexts, rather than prescribing universal ‘best practice’ that often fails. So it fits well with other currents of thought on complexity and systems, (covered ad nauseam on this blog).

But now CGD researchers Bill Savedoff and Rita Perakis have stepped back and taken a long hard look at where CoD has got to thus far. I attended a discussion of the resulting paper “Does Results-Based Aid Change Anything?” last week, and I think it’s fair to say they haven’t exactly been blown away by what they’ve found.

Firstly, donors have been overclaiming: According to Rita and Bill’s blogpost on their paper ‘instead of a revolution in aid, we found a cautious adaptation of traditional programme approaches’.

They found very few programs that actually pay governments for outcomes (four to be precise, although the numbers have risen since they did their trawl). They were GAVI’s ISS (Immunization Services Support) programme; the Amazon Fund (a deforestation programme in Brazil, funded by Norway); an Ethiopian secondary education programme, funded by DFID) and Salud Mesoamerica 2015 (regional healthcare, 8 countries in Central America, funded by the IADB).

They found very few programs that actually pay governments for outcomes (four to be precise, although the numbers have risen since they did their trawl). They were GAVI’s ISS (Immunization Services Support) programme; the Amazon Fund (a deforestation programme in Brazil, funded by Norway); an Ethiopian secondary education programme, funded by DFID) and Salud Mesoamerica 2015 (regional healthcare, 8 countries in Central America, funded by the IADB).

The authors paper identifies four theories for how RBA programmes are supposed to work:

Pecuniary interests. Countries will change their priorities because they need the money.

Attention. Because funds are linked to outcomes, politicians and bureaucrats will pay more attention to results and manage things differently than they would otherwise.

Accountability. RBA agreements make outcomes visible to citizens in funding and receiving countries, allowing them to hold their governments accountable for performance.

Recipient discretion. By linking payments to outcomes rather than inputs, funders give recipients wider latitude to design and implement strategies of their own making.

Out of the 4 case studies, the authors found that 3 were just about ‘attention’ – getting decision makers to think more about

It’s really not that difficult

outcomes. Only the Amazon Fund went further, including some elements of accountability and recipient discretion, and tellingly, that Fund did not come out of the standard aid agency processes. It was proposed by Brazil in 2007 and picked up by climate change staff in the Norwegian government rather than by NORAD.

Elsewhere, the researchers found a ‘Striking lack of transparency on the results of what were actually quite simple programmes’ and thus no impact on accountability (you can’t hold governments accountable if you have no information on what they are doing).

On the plus side ‘the typical concerns with RBA did not materialize, such as corruption, distortions of incentives, or the sacrifice of long goals’, although that’s hardly surprising given that the programmes are such a timid step towards RBA.

The discussion at CGD highlighted a few other issues:

Time horizon: The standard 3 year programme doesn’t give you time to invest upfront in innovation, so if you need to show results quickly, you play it safe. RBA needs to go to 5 year programmes or longer if it is genuinely interested in promoting innovation.

Sustainability: The Brazilian deforestation study got me thinking. Whether or not your RBA project is responsible, if it coincides with a downswing in the rate of deforestation, the Brazilian government gets lots of cash, and that’s great. But when the project ends, if an upswing takes place, and the trees get chopped down and burnt after all, the net effect on the amount of CO2 in the air is the same (Bill argues that a delay at least buys time to sort out a carbon transition, but that seems pretty thin). So maybe RBA works better for largely irreversible changes (eg educating kids) than for reversible ones?

Which leads on to the link between RBA and institutional strengthening. In the long run, only strong domestic institutions are going to deliver sustainable progress on health, education, deforestation etc, but the link between RBA and institutional strengthening seems pretty tenuous (you may need better institutions to get those short term results). Mind you the whole idea that outsiders can strengthen domestic institutions is pretty debateable – so the question of whether RBA is more/ less likely than traditional aid approaches to encourage stronger institutions is both open and very important.

Finally, this paper is only about aid to governments, and deliberately excludes using results-based performance contracts with other recipients such as NGOs. A BOND survey of NGOs about their experiences to date suggests that version of RBA is pretty disastrous.

And here’s CGD boss Nancy Birdsall explaining COD in ten minutes

March 25, 2015

Some healthy scepticism about ‘Citizen Engagement’ (and why I’m excited about MOOCs)

MOOCs are taking over. If you aren’t yet excited about Massive Open Online Courses, you should be. When I was first getting  interested in development the only way to bridge the gap between reading the news and coughing up squllions for a Masters was to cycle through the rain every Tuesday evening to London’s City Literary Institute to sit at the feet of Jenny Pearce and her course on Latin America (I ended up taking over from her, and writing a book based on the course). These days I could stay warm and dry, and listen online to development gurus from around the world. The numbers signing up are colossal – Jeff Sachs reportedly has 14 million students for his MOOC on sustainable development.

interested in development the only way to bridge the gap between reading the news and coughing up squllions for a Masters was to cycle through the rain every Tuesday evening to London’s City Literary Institute to sit at the feet of Jenny Pearce and her course on Latin America (I ended up taking over from her, and writing a book based on the course). These days I could stay warm and dry, and listen online to development gurus from around the world. The numbers signing up are colossal – Jeff Sachs reportedly has 14 million students for his MOOC on sustainable development.

As often happens, the initial surge came in the US, but it’s crossing the Atlantic. Last week I spoke at the LSE at the launch of a MOOC on ‘citizen engagement’, put together by the World Bank, LSE, IDS, ODI, Harvard and Civicus (a sort of crowd-sourced MOOC – even more funky). We spoke a few days after the MOOC went live, by which time 14,000 people had signed up from all over the world.

The discussion was pretty good and although no-one was against citizen engagement (CE), they were strikingly sceptical about the hype around it – no-one is drinking the participation-will-solve-everything koolaid any more. Some snapshots:

The discussion was pretty good and although no-one was against citizen engagement (CE), they were strikingly sceptical about the hype around it – no-one is drinking the participation-will-solve-everything koolaid any more. Some snapshots:

Everyone stole my lines on power, politics and conflict being an essential part of change and transitions to accountability. Linked to that was a clear distinction between using CE as a means of paradigm maintenance and ‘and enabling people to rock the boat’. Owen Barder warned that ‘we need to be careful with the idea that removing confrontation is a desirable outcome’. Duncan Edwards of IDS quoted Andrea Cornwall and John Gaventa’s great call for a move ‘From users and choosers to makers and shapers’ (here’s his take on the meeting).

Healthy scepticism on the impact of donors on CE: the risks of ‘death by consultation’ that changes nothing, ‘facipulation’ and creating Astroturf organizations (they look like grassroots, but are actually synthetic creations hoovering up aid dollars).

The dreaded ‘toolkit temptation’ whereby perfectly good, innovative and adaptive ideas are reduced to one more box to tick.

Vanessa Herringshaw of Transparency and Accountability Initiative pointed to the hypocrisy of dozens of governments that mouth the platitudes on engaging citizens, while at the same time cracking down on civil society space.

There was a healthy degree of scepticism about the game-changing potential of IT, not least because its use is often individualised rather than collective – can it be turned round to promote ‘connective action’ that brings people together and builds ‘power with’?

Some wise words on the dangers of CE fundamentalism: ‘It would be catastrophic if every form of engagement led to an  outcome’ (Fredrik Galtung of Integrity Action). ‘The purpose of government is to reconcile competing interests. They make people do things that they don’t want to do for some greater good. The goal of CE is not to ensure that everyone gets what they want all the time, but to change the power relationship to some fairer form of reconciliation of competing claims.’ (Owen Barder at his magisterial best).

outcome’ (Fredrik Galtung of Integrity Action). ‘The purpose of government is to reconcile competing interests. They make people do things that they don’t want to do for some greater good. The goal of CE is not to ensure that everyone gets what they want all the time, but to change the power relationship to some fairer form of reconciliation of competing claims.’ (Owen Barder at his magisterial best).

Beware short cuts: Owen Barder again (he stole the show a bit): ‘Social contracts cannot be brought about by a series of fixes (CE, but also reforms to tax, property rights, democracy, legal system). They emerge from the evolution of institutions, and that can’t be bypassed or short cut. Our role (as outsiders, aid agencies etc) is to accelerate evolution, thinking less like Dr Frankenstein sticking body parts together, and more like a plant breeder speeding up the variation, selection and amplification of new strains (presume he was referring to traditional plant breeding, rather than GM…..).

Voice is not the same as accountability: one speaker memorably argued that China has lots of accountability and no voice; India the opposite.

As for the MOOC, I would love to hear from anyone taking it. One interesting aspect of now being on staff at the LSE is that I get to see some of the tensions between Open Access and traditional academic culture – a spirited internal email exchange about whether MOOCs will undermine academic standards and more practically, a refusal from the techies to webstream the launch event because they hadn’t got sufficient layers of sign off. Quite funny really.

And at Oxfam we are busily discussing a MOOC to accompany the How Change Happens book, but I think it could go much wider than that. We’re sitting on a pile of internal training materials that would be relatively painless to turn into MOOCs – Oxfam University anyone?

If you’re an acronym junkie, MOOC is just the start. There are fee-charging SPOCs (small private online courses) and (I learned at the event) even SNOCs (small network online courses). I think at this point you can just start making them up and see if they stick.

And here’s a 3m video ad for the course (if you don’t want to join it because it’s already started, don’t worry, there’ll be another one along in a few months)

March 24, 2015

How can India send a spaceship to Mars but not educate its children? Guest post from Deepak Xavier

Oxfam is going through its own (belated but welcome) process of ‘Bric-ification’, with the rise of independent Oxfam affiliates in  the

main developing countries. Oxfam India is one of the leaders, founded in 2008 and focussing its work on 7 of the most deprived states in India. It is rapidly becoming an advocacy powerhouse within India, running campaigns on everything from gender inequality to ‘Stand strong with the Indian government against US bullying and protect access to life-saving medicines for millions across the world.’ Here Essential Services campaigner Deepak Xavier (right) introduces its latest campaign on education, complete with interactive online infographics and online petition.

the

main developing countries. Oxfam India is one of the leaders, founded in 2008 and focussing its work on 7 of the most deprived states in India. It is rapidly becoming an advocacy powerhouse within India, running campaigns on everything from gender inequality to ‘Stand strong with the Indian government against US bullying and protect access to life-saving medicines for millions across the world.’ Here Essential Services campaigner Deepak Xavier (right) introduces its latest campaign on education, complete with interactive online infographics and online petition.

India launched its first Mission to Mars – Mangalyaan – in 2013. Mangalyaan reached the red planet in just 325 days, covering 680 million kilometres. Commending the mission’s scientists, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said “A one-km auto rickshaw ride in Ahmedabad cost 10 Rupees and India reached Mars at 7 Rupees per km.” I do join

RTE campaign interactive graphic

him in congratulating the Indian scientists who made it possible.

But it all makes me wonder what stops a country that can achieve such a scientific feat from providing its children – who are often called future of this country – with their basic rights? The Government recently estimated that there are still 6 million children who are out of school even after 5 years of the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 (RTE Act). What this historic Act promises is just a basic right that every child should enjoy. It makes me feel even worse when I note that out of the total children who are out of school, the majority – 75% of them – belong to just 3 socially marginalised communities (Dalit – 32.4%, Muslims – 25.7%, Tribals – 16.6%). The proportion of out of school children from these communities is almost double the proportion of their share in the population.

The RTE Act has certainly contributed to huge changes in school education. More children are now in schools, more teachers are

India’s cheering scientists

teaching, more children study inside a classroom, and there are many more such changes. But we lag far behind the targets set by the Government in 2010. The final deadline to fully comply with all RTE Act norms was fixed as 31st March 2015. Yes, just 10 days from now. As of now, only 8% of the schools fully comply with all RTE norms. In other words, 92% of schools have failed to comply.

The Mangalyaan travelled at 87,000 km per hour to complete its journey. In the 1,825 days since its implementation, the RTE Act was expected to cover the full distance – reaching full compliance. But it is only 8% of the way there. At this rate, it will take 63 more years to reach full compliance.

But we don’t have to wait for another 63 years to fulfil the basic right of India’s children as long as the Government and people of this country do what they are supposed to do. Just imagine where Mangalyaan would have landed, instead of Mars, if the Indian Space Research Organisation scientists had spent only half of what it costs to get there. Yet that is what is happening in education. Back in 1966, the Kothari commission recommended  that public spending on education be increased to at least 6% of GDP by 1986. Today, nearly after 50 years after the government accepted that recommendation, public spending on education is still hovering around 3.4% of GDP. It has stagnated at around 3% for the last 15 years – at a time the country was witnessing unprecedented economic growth.

that public spending on education be increased to at least 6% of GDP by 1986. Today, nearly after 50 years after the government accepted that recommendation, public spending on education is still hovering around 3.4% of GDP. It has stagnated at around 3% for the last 15 years – at a time the country was witnessing unprecedented economic growth.

India can give every child its fundamental right to education. For this to become reality, we, the people of India need to raise our voices and demand our children’s right to go to school. The Government should become the real duty bearer and increase public spending on education to at least 6% of GDP within the next 3 to 5 years.

After all, sab bachon ka #HaqBantaHai (all children have the right)!

March 23, 2015

Links I Liked

Bit of a (qualified) feelgood to this week’s links.

The IT revolution, Somalia style: goats and sheep carry owners’ mobile numbers for identification [h/t Calestous Juma, photo credit @Lattif]

Germany announces record boost to its aid budget to €7.4bn ($7.9bn = 0.4% of GNI)

Great idea: a new global fund launched to help developing countries fend off Big Tobacco company challenges to their attempts to control a killer drug.

Progress on political voice, women’s empowerment & wellbeing in Ghana, Colombia, Morocco and Tunisia. Smart 3m animation

The percentage of Nigerian women saying it’s OK for a husband to beat his wife fell from 44% in 2003 to 21% in 2013. Progress of a sort, I guess. From a global survey of attitudes to violence against women.

Good post on one of my hobbyhorses: “See no religion, hear no religion, speak no religion”

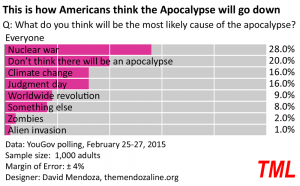

The same number of Americans expect apocalypse through climate change as from judgement day (and 2% of them think it’ll actually be zombies)

The same number of Americans expect apocalypse through climate change as from judgement day (and 2% of them think it’ll actually be zombies)

Making the case for case studies in development practice (and a great example from Lao). Excellent from Michael Woolcock

Top St Patrick’s Day from Channel 4 News. An imam and Irish folk singer who was crowned Gaelic Voice of Ireland.

March 20, 2015

Four roles for the Multilateral System – how well will it perform any of them?

Along with a bunch of Oxfam’s specialist policy wonks, I recently helped Francoise Vanni, our new Director of Policy and Campaigns, put together a presentation on the multilateral system. Writing a new powerpoint is also a pretty good way to generate a blog post – key messages, simply transmitted (assuming you obey the ‘less than 20 words per slide’ rule, and avoid sticking up vast chunks of text or tables, like some academics I know). So here goes (and here’s the slides if you want to nick them Francoise Vanni powerpoint).

Along with a bunch of Oxfam’s specialist policy wonks, I recently helped Francoise Vanni, our new Director of Policy and Campaigns, put together a presentation on the multilateral system. Writing a new powerpoint is also a pretty good way to generate a blog post – key messages, simply transmitted (assuming you obey the ‘less than 20 words per slide’ rule, and avoid sticking up vast chunks of text or tables, like some academics I know). So here goes (and here’s the slides if you want to nick them Francoise Vanni powerpoint).

The Multilateral System (MLS) has huge potential to promote human rights and development, but it is a political construct and so can easily be turned into a tool of dominance by the powerful. There are (at least) four potential roles for the MLS:

Solving Collective Action Problems

Curbing the excesses of the powerful (states, corporations)

Encourage democracy and inclusion

Transfer resources from the richest to the poorest

Solving Collective Action Problems

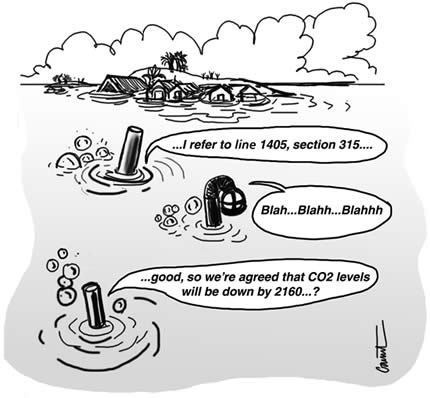

The multilateral system is there to help humanity deal with problems that cannot be dealt with by nation states alone – problems like climate change, rising inequality, or Ebola.

Climate change is the biggest collective action problem ever faced by humanity. Crops are being parched then drenched. Competition for dwindling land and water is on the rise. Companies are polluting and profiting. So far the multilateral system hasn’t shown it can cope with it, nor has it shown it can secure action that is more than the sum of the national parts. This December’s climate summit in Paris might be the turning point we have waited for to secure agreement we need in the fight against climate change. We need it to lift ambition at a national level and send a vital signal to energy and other markets that the world’s political leaders are serious about tackling climate change. Paris is an absolutely pivotal moment.

Climate change is the biggest collective action problem ever faced by humanity. Crops are being parched then drenched. Competition for dwindling land and water is on the rise. Companies are polluting and profiting. So far the multilateral system hasn’t shown it can cope with it, nor has it shown it can secure action that is more than the sum of the national parts. This December’s climate summit in Paris might be the turning point we have waited for to secure agreement we need in the fight against climate change. We need it to lift ambition at a national level and send a vital signal to energy and other markets that the world’s political leaders are serious about tackling climate change. Paris is an absolutely pivotal moment.

Inequality is rising. Last year Oxfam calculated that 85 individuals had the same wealth as the bottom half of the world´s population 3.5 billion people. This year, we updated our numbers and found out that the number of individuals on the megarich bus had dropped to 80. With wealth comes power, and with power the ability to influence political processes and political outcomes, with the danger of rigging outcomes to serve the interests of the few.

Globally tax evasion deprives governments of trillions of dollars – a huge collective action problem, as the race to the bottom on tax means less and less money for governments to spend on vital public services like schools and hospitals. Developing countries may lose $100 billion a year from tax dodging and generous tax incentives – yet they aren’t given an equal voice in the negotiations under way to rewrite the tax rules. This means that current talks exclude more than a third of the world’s population.

That’s why Oxfam is calling for a World Tax Summit, where all countries are invited and where the rights and needs of citizens are prioritised over the profits of corporate giants.

Ebola exposed the systematic underfunding of the World Health Organisation, and the brutal health inequities that show that when it  comes to dangerous pandemics, we are only as safe as the weakest link in the global chain. Again what better case for a stronger multilateral system?

comes to dangerous pandemics, we are only as safe as the weakest link in the global chain. Again what better case for a stronger multilateral system?

Curbing the Excesses of the Powerful

On issues such as trade and investment rules and intellectual property rights, organizations like South Centre and UNCTAD (who organized the event Francoise was speaking at) played a vital role in defending policy space during the high water mark of neoliberalism. Although developing countries have so far fended off multilateral assaults at the WTO and before that in the Multilateral Agreement on Investment, as UNCTAD points out, serious encroachment is taking place through a host of Regional Trade Agreements and Bilateral Investment Treaties. Continued vigilance is needed to oppose efforts to ‘kick away the ladder’ of development, because, as Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang has shown, policy space and industrial policy have played vital roles in the take off of almost all now-successful economies.

Encourage democracy and inclusion

The MLS in general and the UN in particular, has played a huge role in encouraging the spread of human rights, not least for women and girls. As national governments become stronger, more capable and less dependent on aid, the MLS must continue to nudge them along the road to respecting human rights. An important part could be played by the Sustainable Development Goals, but only if they are designed in such a way as to influence national governments, not just the quality and quantity of aid. The SDG discussions this year will be crucial.

Transferring resources from the richest to the poorest

Keeping the global quantity of aid rising during a global recession is an achievement without historic precedent. But in relative terms, aid is of declining importance compared to other sources such as foreign investment and remittances, as well as domestic resource mobilization (from taxes and natural resources). The Addis Financing for Development summit in July is a crucial moment to move forward on all forms of development finance:

In the face of rising inequality and political capture, donors and development partners need to collectively emphasize accountability, transparency, policy coherence, and gender mainstreaming across all financial flows for development.

Donors need to provide assurances to developing countries that growing levels of climate finance are not at the expense of existing funding for development actions like health and education. Climate finance is essential to ensure that global efforts to tackle climate change are distributed fairly, and that poor countries who have done nothing to cause climate are financially supported to adapt to climate impacts and can develop in low carbon ways. However, it has been very difficult to come to an agreement between countries that climate finance should be additional to existing commitments to increase aid to 0.7% of gross national income.

Even though aid is falling in relative importance overall, it remains a crucial contributor to ending poverty: in 43 countries that are home to 221m extremely poor people, aid remains larger than other flows. These 221m people represent one-third of the extremely poor living outside China and India.

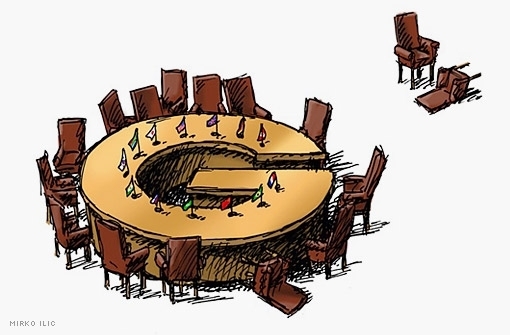

Many feel that in recent years the multilateral system has been broken, that instead of a G20, or G8, what we have is a political black hole that looks more like a G zero – where nothing significant can be agreed. But while it is true that it is very difficult to get progress at the multilateral level, the success last year in getting a global Arms Trade Treaty shows that success is possible.

There is no substitute for a robust multilateral system, one that reflects the realities of today’s global politics and power, rather than those at the end of World War 2, and one that can respond to the huge collective problems that face us all.

March 19, 2015

Modern Slavery: How widespread? What to do about it?

The Economist has a powerful series of articles on modern slavery this week. Sorry this is too long, but they write so well, I struggled to make  cuts.

cuts.

How to reduce bonded labour and human trafficking

“The time that I went into the camp and I looked, I was shocked. Where all my expectations and my happiness all got destroyed, that was the minute that it happened.” So testified Sony Sulekha, one of the plaintiffs in the largest human-trafficking case ever brought in America. He and around 500 other Indians had been recruited in 2005 to work in the Signal International shipyard in Mississippi. Each had paid at least $10,000 to a local recruiter working for Signal, expecting a well-paid job and help in getting a green card. Instead they laboured in inhumane conditions, lived in a crowded camp under armed guard and were given highly restricted work permits. Last month a jury awarded Mr Sulekha and four others $14m in damages against Signal and its recruiters. Verdicts in other cases are expected soon. Signal says it will appeal.

Estimates of the number of workers trapped in modern slavery are, inevitably, sketchy. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) puts the global total at around 21m, with 5m in the sex trade and 9m having migrated for work, either within their own countries or across borders. Around half are thought to be in India, many working in brick kilns, quarries or the clothing trade. Bonded labour is also common in parts of China, Pakistan, Russia and Uzbekistan—and rife in Thailand’s seafood industry (see below). A recent investigation by Verité, an NGO, found that a quarter of all workers in Malaysia’s electronics industry were in forced labour.

Until recently campaigners paid most attention to victims who had been trafficked across borders to work in the sex industry. An unlikely alliance of right-wing Christians and left-wing feminists argued that prosecuting sex workers’ customers would be the best remedy. But the focus is now widening to the greater number of people in other forms of bonded labour—and the proposed solutions are changing. Campaign groups and light-touch laws, backed up by the occasional high-profile prosecution, aim to shame multinationals into policing their own supply chains.

In December Pope Francis and the grand imam of Egypt’s al-Azhar mosque, together with several other religious leaders, launched the Global Freedom Network, a coalition that tries to press governments and businesses to take the issue seriously. The ILO has launched a fair-recruitment protocol, intended to cut out agents, which it hopes will be ratified by national governments.

Two new philanthropic funds are also being established. The Global Fund to End Slavery, which is reported to have substantial seed money from Andrew Forrest, an Australian mining magnate, will seek grants from donor governments and part-fund national strategies developed by public-private partnerships in countries in which bonded labour is common. The Freedom Fund, launched in 2013 by Mr Forrest (again), Pierre Omidyar (the founder of eBay) and the Legatum Foundation (the charity of Christopher Chandler, a billionaire from New Zealand), finances research into ways to reduce bonded labour.

The Freedom Fund’s first schemes include assessments of efforts to free bonded labour in the Thai seafood industry, the clothing industry in southern India and—a harder problem, since the customers are rarely multinationals—in brick kilns in the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

America made human trafficking illegal in 2000, after which it started to publish annual assessments of other countries’ efforts to tackle it. But it has only slowly turned up the heat on offenders within its borders. Australia and Britain have recently passed light-touch laws along the lines of a law requiring transparency in supply chains that was adopted by California in 2010. This requires manufacturers and retailers that do business in the state and have global revenues of at least $100m to list the efforts they are taking to eradicate modern slavery and human trafficking from their supply chains. A firm can comply by simply reporting that it is doing nothing. But it seems few are willing to admit this, lest it upset customers or staff, meaning that the issue is forcing its way on to managers’ to-do lists.

Ending bonded labour will require economic as well as legal measures, says Beate Andrees of the ILO. But she also hopes to see some “strategic litigation”. Nick Grono of the Freedom Fund thinks one of the multinational construction firms preparing Qatar to host the 2022 football World Cup could be a candidate. There is evidence of “wilful blindness” to the terms on which migrant construction workers are being recruited, he says. A successful prosecution could be salutary.

Slavery and Seafood in Thailand

Slavery and Seafood in Thailand

Before he escaped, Maung Toe, an immigrant from Myanmar, laboured unpaid for six months on a Thai ship fishing illegally in Indonesian waters. He had been forced aboard at gunpoint and sold by a broker to the captain for $900. It was the first time he had ever seen the sea.

Mr Maung’s story is told by the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), a charity, in a recent study of trafficking and piracy in Thailand’s seafood industry. The country hosts tens of thousands of trafficking victims, by conservative estimates, many from Myanmar, as well as from Cambodia and Bangladesh. Many of them sweat on trawlers or in vast fish-processing plants. Some were duped by recruitment agents; a few were kidnapped. Others are migrants who were waylaid by traffickers while travelling through Thailand.

Overfishing is partly to blame. Average catches in Thai waters have fallen by 86% since the industry’s large expansion in the 1960s. Such meagre pickings have driven local workers out of the industry and encouraged captains to seek ultra-cheap alternatives. Boats now fish farther afield and stay at sea for months at a time, making slavery harder to spot.

International pressure is mounting. The American government ranks Thailand among the least effective of all countries in fighting trafficking, along with Iran, North Korea and Syria. Food firms in Europe and North America—who together purchase about a third of Thailand’s fish exports—seem concerned. Last year the prime minister, Prayuth Chan-ocha, promised tougher enforcement. At a press conference this month, the authorities said they had identified nearly 600 trafficking victims in 2014.

But cynics worry that the military government in power since a coup last May will turn a blind eye again once the immediate threat to exports fades. Frank discussion of the business seems to be discouraged. Two journalists in Phuket—an Australian and a Thai—may face a defamation trial for republishing sentences from a Reuters article alleging that navy personnel had helped traffickers. In January campaigners forced the government to drop a plan to put convicts to work on fishing boats—a policy probably intended to dampen demand for bonded labour. A broader shift towards respecting human rights seems some way off.

Many of India’s “modern slaves” labour in appalling conditions in brick kilns or breaking stones in quarries. Typically they are  recruited by agents offering real jobs and then trapped by accepting an advance on earnings, which turns out to be a loan at exorbitant interest that no worker can ever hope to repay. The boss then suggests that the worker bring in his wife and children, and soon the entire family is enslaved. Unpaid debts can be bequeathed from one generation to the next.

recruited by agents offering real jobs and then trapped by accepting an advance on earnings, which turns out to be a loan at exorbitant interest that no worker can ever hope to repay. The boss then suggests that the worker bring in his wife and children, and soon the entire family is enslaved. Unpaid debts can be bequeathed from one generation to the next.

Despite having been illegal in India for several decades, such practices continue. Corrupt politicians and police, the caste system and an illiterate workforce with few alternative ways to make a living combine to keep millions in bonded labour. Yet there are examples of activists successfully intervening to free such slaves and, crucially, to keep them free.

One notable example is the Society for Human Development and Women’s Empowerment [nb can’t find a link for this – have they got the name wrong?], an NGO that organises rescues from brick kilns near Varanasi, a city in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. It seeks out victims, teaches them their rights, organises them into support groups and works with government officials both to free bonded labourers and to make sure they get benefits they are entitled to and school places for their children. It also provides training, especially to women, so that they can earn money in other ways. Some freed workers have even been helped to set up their own brick kilns.

The Freedom Fund is now piloting a “hotspot” strategy that seeks to show how bonded labour can be eradicated from entire districts by helping the most effective NGOs to work together. Grants of up to $200,000 have been given to 17 NGOs in 27 districts in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, where bonded labour is most prevalent.

These efforts, although positive, barely scratch the surface of a huge problem. So the Freedom Fund has recruited the Institute for Development Studies at the University of Sussex and Harvard University’s FXB Centre for Health and Human Rights to study the hotspots to discover what is working and whether it can be scaled up fast. The first results are due in a few months.

And here’s Freedom Fund’s 5m intro to modern slavery

March 18, 2015

Why is Britain such an outlier on aid?

My friend Ha-Joon Chang is Korean, and argues that for a development economist, growing up in South Korea is like being a physicist

Just add ‘overseas aid’?

at the birth of the universe. I was reminded of that when the UK parliament enshrined spending 0.7% of gross national income on aid in national law last week – for an aid wonk, being British means you live, talk and debate in a bubble characterized by a high degree of interest, resources and a constant and exhilarating exchange of ideas. When I travel elsewhere in the developed world (Australia, North America, continental Europe), the contrast is painful: development ministries being closed down, budgets cut, and (at the risk of doing an injustice to any number of talented, dedicated activists and researchers) a palpable sense of being marginal to political debate and priorities.

The UK now accounts for roughly 1 in every 7 of the world’s aid dollars, and DFID is the only remaining cabinet level, operational aid ministry. The UK-based INGOs are disproportionately large and influential (4/11 of the largest are headquartered in the UK, and of the remainder ActionAid , now based in Johannesburg, has British roots). We have IDS, LSE, ODI and a bunch of other consultants and top academic institutions on developmental issues. So why is the UK such an extreme outlier on development? Is this just about a hangover of post-colonial guilt? Or is this more like an industrial cluster – a developmental Silicon Valley?

I raised this last week during an online debate on the Guardian Development Professionals Network and got some interesting thoughts. Action Aid’s Nuria Molina felt that “the ‘original sin’ is the post-colonial guilt, probably. But this is debatable because other former colonial powers don’t have such an industry. Today, I think it’s better explained by the very existence of an industrial cluster which, like any bureaucracy or organisation, really, tends to be self-preserving. For instance, there are many countries where I have lived where Development Studies degrees do not exist at all. Development is not a science, but rather people study politics and participation, or sociology, or water engineering, or medical degrees, etc. and they contribute to development – mostly at domestic level, but also overseas – according to their expertise.

Zoe Marks came back with ‘The question, though, is if we work with the ‘industry’ metaphor: what are we producing? Who determines supply and demand? To which I replied: OK. In my limited

understanding, the secret of clusters like Silicon Valley is that they are particularly creative and productive because they generate externalities between firms, e.g. on training and career development, and the buzz of networking produces piles of new ideas. The UK aid cluster and its revolving door between thinktanks, NGOs, media and DFID churns out a horrendous tide of aid jargon, but also some useful learning and progress. Their ‘product’ is knowledge and narrative, both academic and practical, about development, which is of interest both to our domestic market (including the public that funds us) and as an export.

But clusters can go out of business when new, lower cost entrants enter the market – eg when East Asia nearly destroyed the Brazilian shoe industry. Then the cluster is forced to move up market e.g. to design or higher quality, if it wants to survive. Perhaps the Aid equivalent would be that UK organizations focus on policy and research, and let low cost entrants like BRAC International do the service delivery. Worth developing?

Rashmir Balasubramaniam liked the cluster approach: ‘I’d be inclined to call it a cluster. Having just moved back here after some 10 years in the US, I can report that there’s a global health cluster rapidly developing in Seattle that is having increasing local and global effects. It is inspiring and drawing more and more people from within the US and from around the world to it, thus expanding the cluster and its influence. Such clusters reach a tipping point, beyond which there may be no (easy) turning back. Is that what happened to the UK? And has anyone quantified the impact of this development cluster on the UK?’

In this argument, the 0.7 vote is an outcome of the UK’s busy Aid and Development cluster, which generated both the campaign pressure, but also the underlying critical mass of knowledge, interest, concern and consensus, that led to last week’s extraordinary vote. Your views please!

This post also appears on the Guardian Development Professionals Network blog.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers