Duncan Green's Blog, page 167

April 15, 2015

Where have we got to on Theories of Change? Passing fad or paradigm shift?

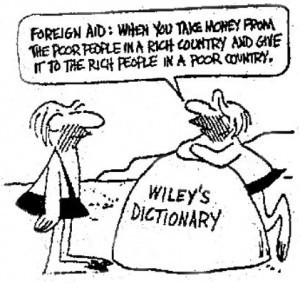

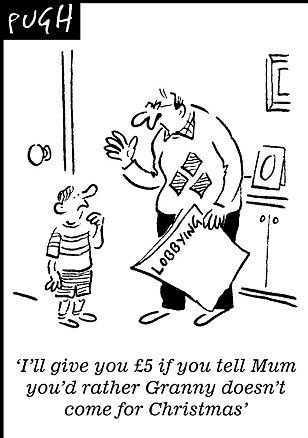

Theories of change (ToCs) – will the idea stick around and shape future thinking on development, or slide back into

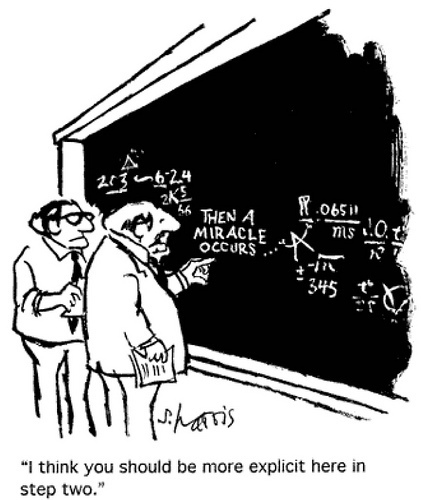

My favourite ToC cartoon

the bubbling morass of aid jargon, forgotten and unlamented? Last week some leading ToCistas at ODI, LSE and The Asia Foundation and a bunch of other organisations spent a whole day taking stock, and the discussion highlighted strengths, weaknesses and some looming decisions. (Summary, agenda + presentations here)

According to an excellent 2011 overview by Comic Relief, ToCs are an ‘on-going process of reflection to explore change and how it happens – and what that means for the part we play’. They locate a programme or project within a wider analysis of how change comes about, draw on external learning about development, articulate our understanding of change and acknowledge wider systems and actors that influence change.

But the concept remains very fuzzy, partly because (according to a useful survey by Isobel Vogel) ToCs originated from two very different kinds of thought: evaluation, (trying to clarify the links between inputs and outcomes) and social action, especially participatory and consciously reflexive approaches.

At the risk of gross generalization, the first group tends to treat ToCs as ‘logframes on steroids’, a useful tool to develop more complete and accurate chains of cause and effect. The second group tend to see the world in terms of complex adaptive systems, and believe the more linear approaches (if we do X then we will achieve Y) are a wild goose chase. These groups (well, actually they’re more of a spectrum) c0-exist within organisations, and even between different individuals in country offices.

One confusing consequence is that the term ‘Theory of Change’ describes both a formal document and a broader approach to thinking about development work. For some Theory of Change is a precise planning tool, most likely an extension of the ‘assumptions’ box in a logframe; for others it may be a less formal, often implicit ‘way of thinking’ about how a project is expected to work.

Craig Valters’ favourite ToC cartoon

And when used as a planning tool, ToCs are being implemented in addition to logframes rather than instead, and grant recipients are reporting to donors against the latter, with predictable results: ‘At end of day, we have to prioritise logframes – that’s what you’re being graded against’.

I came away feeling that this is all generating so much confusion that we actually need to find new words to describe the different understandings and approaches to ToCs.

For a start, it might help to distinguish between Theories of Action, which focus much more on whatever intervention is being discussed, and Theories of Change, which unpack how the system is changing (or might change in future) even absent our intervention. In my experience, the organizational imperative to do stuff, raise money, demonstrate impact, or just be active means that people spend far too little time studying and understanding the social, political or economic system before intervening (books like Portfolios of the Poor are a brilliant exception).

Enough ToCs are now being discussed and included in project plans and implementation for us to start seeing how they work out in practice. The leader on this is probably The Asia Foundation, with its collaboration with LSE, (discussed last year in Craig Valters’ excellent paper) but others are joining in – see the Comic Relief review or this 2012 study by CARE of the use of ToCs in 19 peacebuilding projects in Uganda, Nepal and the DRC.

Some of the more interesting benefits of ToCs identified during the seminar included:

Opening up a conversation with donors about more realistic programmes and aims, allowing both donors and recipients to challenge unrealistic expectations and over-claiming

Making explicit a lot of the implicit/tactic knowledge and analysis that underpin what aid agencies actually do (especially important given high levels of staff turnover – see below)

Motivation: ‘reminding everyone why they are doing this’

More quickly identifying things that aren’t working, so we can stop doing them (and spend the money on something else) – this is an aspiration, but Craig says he has so far seen few signs of it happening.

Some other impressions from the discussion:

1. It all comes down to people: ‘The ones who like ToCs are the development cynic types kicking against standard agendas/normative claims, who like having a language that forces people to think harder. It’s often those with more research/academic backgrounds. The others are not rejecting ToCs, but just not investing so much in them – they have lots to be getting on with.’ At the moment, all the success examples seem to require exceptional ‘development entrepreneurs’, but they are in short supply – what would a ‘where there is no Jaime Faustino’ approach look like?

2. Down with diagrams? OK, I am not a visual person (at school I was always rubbish at art), but I really hate the diagrams that

Imagine being presented with this on your first day

seem to accompany ToCs (see example). Others disagreed – simple clear diagrams can be a great comms tool, much more accessible than 40 page narratives. Trying to cram everything into a single diagram by just adding more and more boxes and arrows may be helpful for those participating in the exercise, but within months, they will all have left (staff turnover again) and the incomers will stare at the resulting visual spaghetti in terror and incomprehension. Maybe we should develop a special kind of ToC diagram that self destructs after 10 seconds, Mission Impossible style, and has to be endlessly redrawn by each new staff team?

3. How did everything get so top-down? think one cause lies in ToCs’ links with Political Economy Analysis: ‘a brief moment of omniscience when you can do a PEA and understand power relationships’. The ‘you’ in that sentence is always a consultant, a researcher, or an aid agency staffer – never a community or a (growl) ‘beneficiary’. Where are the bottom up, participatory ToCs? Why are IDS and Robert Chambers so absent from this discussion? ToCs talk a lot about power in other settings, but ignore power relations in our own organizations – what if they become ‘just another corporate stick to beat people with’? NGOs like Peace Direct and CAFOD are doing some bottom up work on this, but we need to be much more vocal.

4. Maybe we do need a toolkit after all: toolkits get a really bad press – restrictive, ignoring local context and tradition etc etc. But what’s the alternative? I fear it is the overpaid consultant or other expert flying in to explain all (see previous point) – ToCs could end up excluding local staff, partners and communities even more than the traditional approach. A good toolkit could include and reassure staff who don’t spend their whole lives on this stuff, but the question remains how to design it so that it doesn’t impose outside templates and preclude imagination, innovation and adaptation. Seems to me a toolkit would need to set out the kinds of questions to ask in designing a ToC, and the process for then implementing and adapting it. The Asia Foundation seems to be developing one, involving teams keeping and updating timelines of the evolving ToC, and having regular ‘time outs’ to revise it.

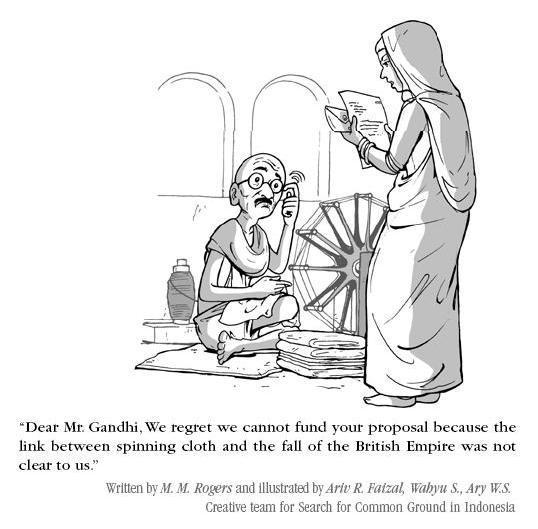

A close second

As for where we go from here, I think we have to consciously differentiate between ToCs as a bigger, better blueprint, all designed up front, and ToCs as a compass for helping us find our way through the fog of complex systems, discovering a path as we go along. But that will only happen if we can help people overcome their hunger for the certainty, however illusory, provided by linearity and up front design. At least donors are up for this – one DFID rep said she wanted ‘truly strategic partnerships in which not knowing is seen as a strength’.

Meanwhile, if ToCs are to endure, we need to demonstrate some quick wins from using them, and make it easier to do so. And NGOs and others need to step up and join TAF in offering themselves as guinea pigs.

[With thanks to Craig Valters for voluminous comments on my (much shorter) first draft]

April 14, 2015

What has cancer taught me about the links between medicine and development? Guest post by Chris Roche

My friend and How Change Happens co-conspirator reach some interesting insights into the links between medicine and development.

In July last year I was diagnosed with a pancreatic neuro-endocrine tumour. This is a rare disease and thankfully usually not as lethal as exocrine pancreatic cancer. Some people getting this news decide to take up skydiving, go bungee-jumping or get rip-roaringly drunk: I partially retreated into what Duncan would call wonkiness.

In my varied reading to try to understand this disease and how it is treated I have come across a range of articles, blogs and podcasts: some of which have been useful and interesting, others not so much.

Recently I listen to a podcast on the latest genetic research into pancreatic cancer on the ABC Health Report, which involved an Interview with Andrew Biankin who is Regius Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow. There were striking parallels with some of the recent debates on Doing Development Differently or Thinking and Working Politically, and how such approaches might be measured, notably:

Yup, that looks messy

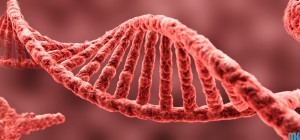

The complexity and messiness of change. ‘There are some cancer cell genomes that are very quiet, there’s not a lot of chunks missing, whereas some are very unstable, and so you’ve got a lot of activity going on, big chunks of DNA are floating off, popping onto other chromosomes, and really it’s a mess.’

So, in a similar way to development processes there seem to be few, if any, single factor explanations for change. Hence the interest in methods that seek to look at combinations of factors.

The degree of uncertainty about what works, for who and the danger of averages. ‘So when you think about treating cancer you don’t think about one drug for 100 patients, you think maybe 20 drugs for 100 patients. You want to match the right drug to the right patient….So you can’t just spray the drug to everybody, you’ve got to find out who’s going to benefit from it.’

So while there may be many people with this form of cancer, their particular genetic make up means that individuals will need differing combinations – and sequencing – of treatments. Arguably not so different to the fact that many people may face a particular abuse of human rights, but how those rights might be fulfilled will take a different combination of actions and actors depending on the context.

The adoption of an approach more akin to emergent discovery, and using the ‘natural variation’ in both patients and their treatment to identify ‘signals’. ‘So what we are seeing is really just some small signals. We do what we call a discovery, where we follow our patients, almost like a clinical trial. We couldn’t change their treatment but what we could do is follow what sort of treatment they received. And we are starting to see some relationships between the sort of treatment they received just by chance and the underlying genomes.’

So this is all about trying to find explanations for variations in outcomes, with their origins in both the variations of treatment and individuals’ genetic characteristics. It is after the fact analysis, unlike designed experiments, which puts a value on natural variation which is especially useful for complex phenomena.

Identifying Exceptional Responders ‘[W]hat we are seeing in some of those circumstances is what we call exceptional responders. ….If we dig into these cancer genomes and start to understand these differences then perhaps we will understand why a particular patient responded so dramatically and why another didn’t.’…

If variation in outcomes is the norm, then the nature of this variation should be explored and exploited, instead of focussing on average effects. The emphasis is on what might be called in development-speak in-depth case studies and exploring positive deviance to investigate what lies behind and contributes to particular patterns and outcomes.

The importance of picking patients rather than a random allocation over a wide group if one is really going to  understand how individual patients are responding to a variety of treatments. ‘The way we’d approach it is that we would develop what we call a biomarker hypothesis. That is we have some biological marker, whether it be a genetic test or some other test, as to why we think this patient responded dramatically. We might take this into the laboratory and do a few extra experiments to understand it better, and then we change the way we perform a clinical trial. We pick the patients that we think are going to respond based on this biomarker, and we treat those patients.

understand how individual patients are responding to a variety of treatments. ‘The way we’d approach it is that we would develop what we call a biomarker hypothesis. That is we have some biological marker, whether it be a genetic test or some other test, as to why we think this patient responded dramatically. We might take this into the laboratory and do a few extra experiments to understand it better, and then we change the way we perform a clinical trial. We pick the patients that we think are going to respond based on this biomarker, and we treat those patients.

So in some cases in order to develop a testable hypothesis or dare I say it ‘theory of change’ one has to explore a limited number of selected cases in depth, and purposively choose those candidates likely to respond based on that theory.

New ways to do clinical trials are needed in order to ‘fail early and fail cheaply’ using smaller trials and stepwise approaches. In this way more approaches can be tested ‘rather than just putting your money behind one horse and hoping that it works’. But as in much of the development world ‘the system isn’t set up for it, the regulators aren’t set up for it. Changing that is going to be our biggest challenge as a community.’

So in the same way the development sector is now talking about ‘iterative adaptation’, it seems that the medical profession is also struggling with how orthodox ways of doing things can crowd out incentives for innovation.

And some of this has to be driven by patients. ‘The consumers or patients and the society in a broad sense will have to play a major role, to direct us into a changing paradigm of how we approach not just cancer but other diseases… [s]o there’s a piece about education and training that needs to happen, not only for practitioners but also for patients.’

Similarly, a number of commentators have stressed in the development arena the potential of those who are meant to benefit from the aid system, and citizens more broadly, having a greater voice in providing feedback and shaping priorities. This is important not just to improve performance but to put pressure on the ‘system’ to provide incentives for reform.

Now of course there are lots of differences between process that involve medical treatments and development processes, which are clearly not ‘treatments’ in the same way. Furthermore there are legitimate concerns about the uncritical borrowing of methods and evaluative process from one setting to another, not least when power and politics play very different roles. I am not suggesting that a replication of precisely this form of approach is appropriate for development agencies.

I am also aware there are a number of risks associated with personalised medicine, including that this emphasis might come at the cost of addressing mass diseases for which common treatments are known. Not unlike development debates about focusing on known technical solutions and the ‘science of delivery’.

However what I find interesting is that when it comes to complex problems and high levels of uncertainty, there seem to be some common generic approaches across different domains, as well as some common challenges and risks. This provides a rich terrain for exchange and learning.

I am glad to say my cancer is currently in remission following the removal of the tumour last August. You might argue I have a vested interest in seeing systemic changes in both the medical and development areas.

My thanks to Rick Davies of the excellent MandE News for his sage advice on how best to communicate some of this!

April 13, 2015

Fit for the Future? Systems thinking and the role of International NGOs – draft paper for your comments

I’m committing potential hara-kiri by giving a DFID staff talk on the future of INGOs tomorrow lunchtime (Wednesday) – if you’re an FP2P reader in DFID, do please come along. Here’s the background and a call for

The challenge: how to take a supertanker white water rafting?

comments on the draft paper I’m presenting: (INGO futures, Green v5 April 2015 (edited)).

Just before Christmas, Oxfam boss Mark Goldring collared me in the canteen and off the back of a recent blog post, asked me to write a ‘provocative paper’ on the future of INGOs. Another one? My heart sank. The standard format goes:

Everything is changing. Mobile phones! Rise of China! Disintermediation!

Everything is speeding up. Interwebs! Instant feedback! Fickle consumers!

You, in contrast are excruciatingly slow, bureaucratic and out of touch. I spit on you and your logframes.

The conclusions then flounder about a bit in the latest development jargon – resilience, leverage, disruption, transformative, innovation etc (add/delete/combine as appropriate) and urge us all to……

Transform or die!

Then we all go home.

Now I’m not saying this is wrong – quite a few entries on this blog follow a similar format. But how to make this paper a bit different (or at least more interesting to write)? So I decided to come at it from a different angle– what do some of the changes in the way we think about development (systems thinking; ‘doing development differently’ ) imply for INGOs?

Here’s the exec sum, but trying to summarize a 15 page paper in a single page has, I’m afraid ended up making it sound much like all the other futures papers. What I’d really like is for you to comment on the full paper, which I will revise and publish after Wednesday (unless the discussion goes horribly wrong and we all agree that INGOs have no future, of course).

Here’s the exec sum, but trying to summarize a 15 page paper in a single page has, I’m afraid ended up making it sound much like all the other futures papers. What I’d really like is for you to comment on the full paper, which I will revise and publish after Wednesday (unless the discussion goes horribly wrong and we all agree that INGOs have no future, of course).

‘After briefly summarizing the main trends in international development, this short paper concentrates on two main issues: how is our understanding of development changing, and what are the implications of all the above for the future role of INGOs? The paper is intended to provoke discussion, rather than offer a balanced overview. It does not represent Oxfam policy.

Increased attention to systems thinking in development raises profound challenges for INGOs, highlighting the folly of many simple linear interventions, and the merits of alternative approaches such as bringing together stakeholders to find solutions together (convening and brokering), multiple experiments and rapid iteration based on fast feedback and adaptation. The discontinuity of most change processes also underlines the need to be able to spot and respond to potentially short-lived windows of opportunity, such as shocks or moments of political flux.

Unfortunately, a simplistic interpretation of private sector thinking is also pushing aid agencies towards a linear ‘Fordist’ approach to going to scale, even though large parts of the private sector have long since abandoned it in favour of systems thinking, disruption and innovation.

How should INGOs respond to this changing environment? How can they plan and operate once they accept that in a complex system, they cannot know what is going to happen? There are numerous options, most of which would entail a substantial change in working practices.

At the heart of these changes is the need across all aspects of Oxfam’s work to relinquish a command and control approach, in favour of embracing a systems approach. In terms of investment, this means increasing the ratio of ‘change capital’ to ‘delivery capital’.

Such change poses tough questions, including:

1. Does size matter? Is working in this way best done by large INGOs with their advantages of large knowledge base and economies of scale, or by a cluster of more agile guerrilla organizations like Global Witness, Avaaz or single issue institutions like the Ethical Trading Initiative?

2. How can we identify and address the sources of inertia? Unless we do so, these kinds of discussions are unlikely to reach a different outcome.

3. What does this mean for our staff? What would need to change in terms of HR practices (recruitment, training, performance management, incentives and internal narratives) to become an organization with a better balance of planner s and searchers (entrepreneurs)?

4. And how could such an organization be funded?!’

Over to you – looking forward to your comments.

April 12, 2015

Links I Liked

Disarming (if unintentional) honesty: Oil company advertising has changed a bit since 1962 (not sure about their practice  though)

though)

The Jeevan Bindi, which doubles as an iodine patch and could save millions of lives [h/t Nisha Agrawal]

Global obesity: 2.1 billion people are overweight or obese. It causes 5% of all deaths and costs $2 trillion a year. 60% of all obese people live in developing countries. Still think it isn’t a development issue?

Two brilliant, grim backgrounders on Middle East meltdowns:

On Yemen, Helen Lackner argues that Saleh not the Houthis has the guns, and the country is starting to look like 1980s Lebanon

And some powerful, if depressing reporting from inside Baghdad on the state of the Iraqi conflict, [h/t Jon Lee Anderson]

And some powerful, if depressing reporting from inside Baghdad on the state of the Iraqi conflict, [h/t Jon Lee Anderson]

12 years on from this Donald Rumsfeld memo and the hubris is still breathtaking

Which countries are good/bad at turning econ growth into social progress? The 2015 Social Progress Index

How do poor people understand corruption? Differently from anti-corruption wonks, according to this Interesting survey from Papua New Guinea

Why Indians’ son preference leads to them being shorter than Africans. [h/t Chris Blattman].

Please take two minutes to watch this totally extraordinary April Fools Video Prank in Math Class. Gloriously nerdy

April 9, 2015

Do Aid and Development need their own TripAdvisor feedback system?

I’ve been thinking about TripAdvisor recently, as a model of fast, crowdsourced feedback which highlights rubbish hotels and

We’re watching you-hoo

restaurants, and creates pressure for them to shape up.

There’s plenty of rubbish performance in the aid and development sector, but our feedback loops are mainly limited to conversations in corridors and the occasional email. So what would be your top candidates for a developmental TripAdvisor?

Let’s start with aid organisations themselves. My colleague James Whitehead asks: “Is there space for ‘Rate My Aid’? In a humanitarian crisis the affected populations are often over-surveyed yet have very little voice in the services they receive. Feedback from communities could be cross-referenced against data on back donors to create a leaderboard of best UN agencies, best INGOs, best local NGOs, and worst… If I was a donor, I might look to the leaderboard before I looked to the project report – to what beneficiaries say about the service rather than what the service deliverer says about it.”

Aid organisations could rate each other too. Imagine a system where grant recipients could feed back anonymously on the behaviour of their donors; do they listen to you? Make unfeasible reporting demands? And vice versa – did money go missing? How big were the over-runs? Which ones really delivered exciting programmes?

Another topic could be the corporations who are looking for NGO/official aid agency partners – some of this is a genuine interest in development, some is PR spin. It would be great if you could just click on the feedback for any given company and find out who is serious, and which ones are just Uber/UN Women PR disasters in the making.

Another topic could be the corporations who are looking for NGO/official aid agency partners – some of this is a genuine interest in development, some is PR spin. It would be great if you could just click on the feedback for any given company and find out who is serious, and which ones are just Uber/UN Women PR disasters in the making.

But why stop at organisations? What about individuals? Here’s where it gets a little trickier.

What about rude aid workers? When humanitarian agencies and their partners are filling in a gap in state provision, a government could easily insist that all aid workers wear a unique identifying number like police officers. Combined with clear crowdsourcing you could easily see which agencies treated people with dignity and which staff might need further training. The days of humanitarian agencies acting as unaccountable non state actors could be numbered…

Consultants: they charge the earth, often for substandard work. How do we find out in advance which ones are good, and which ones just endlessly cutting and pasting the conclusions from their last report?

Journalists: they phone you up, suck your brains dry in search of new ideas for their next piece. Which of them actually write

Not any longer?

anything as a result, or credit you or your organization when they do so?

Peer Reviewers for research proposals: Half of them don’t deliver, or use the opportunity for cathartic venting about their hobby horses, rather than actually reviewing the proposal.

Civil servants: which ones really listen and interact, which go through the motions?

Campaigners and Advocates: Do Government or World Bank staff get to comment on how they feel about the work of different aid agency lobbyists?

Some design issues:

There is likely to be a huge difference between feedback from targets and from peers – any way to differentiate?

Everyone will try and game the system (‘sure I’ll take that meeting, but you have to give me a good review’). I wonder what TripAdviser does to avoid that?

The dangers of blacklists: at the very least you would need an appeal procedure against unfair reviews. Would that make it unfeasibly expensive and bureaucratic?

I sent these thoughts to a couple of IT accountability gurus: Martin Tisne at Omidyar asked some good questions:

‘Is it 2-way or 1-way? Who is the ‘client’ for this type of platform? With TripAdvisor, the clients are the paying customers of the hotels – i.e. it’s not 2-way, the hotel does not get to exercise much choice in terms of the customers it takes on or not, no  black listing etc. Uber and the like purport to have a 2-way system with customers rating cab drivers and cab drivers rating customers but I suspect that on the whole it’s the cab drivers who are really being assessed rather than the other way around. So what are the experiences out there we can learn from that are genuinely two-way and what have they learned about [dis-]incentives to publish and how to deal with conflicts of interest?’

black listing etc. Uber and the like purport to have a 2-way system with customers rating cab drivers and cab drivers rating customers but I suspect that on the whole it’s the cab drivers who are really being assessed rather than the other way around. So what are the experiences out there we can learn from that are genuinely two-way and what have they learned about [dis-]incentives to publish and how to deal with conflicts of interest?’

While Tom Steinberg added some sage advice, based on his experience of setting up lots of such feedback sites in the UK:

‘The art to succeeding here is to start by choosing just one kind of review of one very carefully chosen kind of service – one that has been chosen to minimise the perverse incentives and so on. Try to get that very narrow service working and then move on from there.’

What do you think?

An edited version of this piece appears today on the Guardian Development Professionals blog.

April 8, 2015

How businesses can save the world (when their shareholders aren’t breathing down their neck)

Erinch Sahan, an Oxfam ag and supply chain wonk who is currently leading its Food & Climate Policy and Campaigns, argues that the best way to understand a company’s approach to doing good is by askin g who owns it.

g who owns it.

When it comes to the private sector, the biggest mistake the aid world makes is to see business as a homogeneous entity. In our enthusiasm for development led by private sector growth, we forget to ask: “what kind of a business world do we want?” and “what does inclusive and responsible business look like?” This may sound indulgent, when so many countries are in need of so much more investment and growth. But asking about the kind of businesses we want isn’t a case of letting ‘perfect be the enemy of the good’. It’s a question of maximising our impact on poverty (and as a side-effect building a nicer economy).

So far, I sound like a typical NGO private sector preacher – highlighting that quality is as important as quantity when it comes to private sector development. But bear with me, I promise to try to say something you might not have heard before.

Some businesses and investments are more equal than others

Not all investments are equal in their social impact. Otherwise, ‘impact investing’ wouldn’t exist. What makes some businesses and their investments better socially than others? The ability to take a course of action even when it hurts their bottom line.

When it’s win-win (ie; social and commercial interests align) and the business case adds up, any business can take the high road. It’s when the high road isn’t the most profitable and means you leave money on the table (or incur a significant additional cost) that you separate the wheat from the chaff.

It is very often NOT win-win – empirical studies say so

In case you need convincing as to why there isn’t always a business case to do good (as so many in the donor and sustainability world claim), here are a few scenarios:

In case you need convincing as to why there isn’t always a business case to do good (as so many in the donor and sustainability world claim), here are a few scenarios:

For workers on farms in supply chains to receive a living wage , companies need to pay more to their suppliers (and unfortunately the business case based on productivity gains rarely cuts it).

For companies to acquire land fairly (ie; avoid land grabs) will usually mean they pay more for the land.

For workers to have stable employment, companies have to give up negotiating power and make a commitment to employ someone longer-term(even when laws or union power doesn’t force them to).

If the most profitable option was always the most beneficial for society, why would thriving businesses so often be burning down forests, paying poverty wages and marketing junk-food to children? Academics have also looked into this and the conclusion is: “the evidence of a positive correlation between private sector social and environmental initiatives in developing countries and business performance is often weak. The business case on the environmental side is often stronger (e.g. energy efficiency often linked to cost savings)”.

But you will still read many reports of why there is always a business case for sustainability. These often focus on intangible benefits, such as managing reputational risk or benefits to brand (what about companies without consumer brands?). Or, the business case revolves around a plea to avoid free-riding, and instead protect global commons and invest in common goods, because we all need it. Overall, the business case is rarely more than a collection of anecdotes that show that sometimes – but only sometimes – there is a business case for doing the right thing.

A new -ism: Business Case Enthusiasm-ism

So why does the business sustainability establishment work so hard to avoid acknowledging that doing good usually costs money? One initiative that recently emailed me declares with concern: “Despite the evidence, many investors seem unconvinced that sustainable businesses are as profitable as any other”. This was in response to a Morgan Stanley survey finding that most investors (54%) believe sustainable investing involves a financial trade-off (providing the feel-good factor in exchange for lower returns). Investors and business people know what makes them money – it is unlikely NGO or sustainability types will teach them something about how to make more money. Enthusiasm for the business case for sustainable and responsible business only keeps us on the treadmill of the current model of shareholder capitalism – a model where companies must pursue every cent of last profit, at every cost (as long as it’s legal).

When we push the business case for sustainability, we shut down questions like: “what policies will promote the right kind of business structures with the right incentives?”. Our misguided line is: “the current corporate model is fine – business leaders just need to realise they can make more money by doing good”.

If we can’t rely on the business case, what do we do?

We need to promote or create the right kinds of companies. Some companies do more than others to go the extra mile and will compromise on profits when the drive for profits clashes with the interests of people and planet (though don’t be fooled by the 3P – triple bottom line rhetoric, everyone claims to embrace it). We must go beyond rhetoric and look at the governance, ownership, structural or cultural factors that distinguish companies who prioritise sustainability and positive social-impact over absolute maximisation of profit. In other words: what’s in the DNA of companies who ‘do good’ even when it hits their bottom line?

The clue lies in ownership

A recent World Bank event I spoke at show-cased a few companies that claim they genuinely prioritise doing good. The CEOs

If only it were that simple

of Novo Nordisk and Lego both spoke passionately about how they have made real long-term investments that had positive impacts. I can’t verify or discredit their claims as I’m mostly an ag/supply-chains guy, but in the case of both companies, foundations with a mission statement beyond profitability hold significant shareholdings (in Novo Nordisk’s case, it’s a majority voting rights held by the foundation). We also heard from the Social Sustainability Manager of H&M, a giant in the garments industry, who also showcased some initiatives that appear to push the envelope on social impact (including on initiatives with an arguably weaker business case, such as committing to a living wage in its supply chain workers in Bangladesh and Cambodia). H&M has a single family that holds the majority of voting rights.

Last week, I was at the BRAC Bank headquarters in Dhaka, meeting with a manager in their SME financing section. BRAC is an NGO that is thriving based on profits from social enterprises (including BRAC Bank). The group is huge and growing, working in a range of sectors from agricultural trade and finance, to selling services to farmers, to fisheries, storage and paper. Apart from there being a zillion reasons to look into BRAC (including that it shows social enterprises can thrive commercially in very tough places!), BRAC shows us what can be possible when shareholders salivating over every inch of additional profit aren’t breathing down the necks of business leaders. BRAC enterprises aim to make a profit but aren’t uncompromising about it.

For instance, when BRAC’s milk-chilling stations started losing them money, they kept them open to allow some of the poorest farmers to get fair prices for their milk. BRAC is absolutely focused on commercial sustainability, but it does compromise when provided with an opportunity to make significant social contributions. It’s this approach that means that BRAC Bank ranks fourth in Bangladesh in terms of size but eighth in terms of profitability (according to a manager at the bank). At BRAC Bank, they are more focused on growing their lending to SMEs than they are on growing profits. A corporate model where adequate, not maximum profits drive decisions?

Anecdotally, I’m starting to gain a picture of the DNA of companies based on their ownership:

1) Short-termist baddies – Companies driven by short-term financial interests of shareholders, who can only ever seriously invest in sustainability/responsibility if there’s an immediate and clear business case

1) Short-termist baddies – Companies driven by short-term financial interests of shareholders, who can only ever seriously invest in sustainability/responsibility if there’s an immediate and clear business case

2) Enlightened self-interest / patiently owned – Companies with a longer-term financial horizon, who can invest in sustainability/responsibility if there’s at least a business case in the longer-term

3) Nice shareholders – Companies with shareholders who allow investments into sustainability/responsibility even where there’s a weak or hazy business case (e.g.; majority voting rights held by a foundation or a family with benevolent intentions)

4) The good guys (social enterprise?) – Companies that want to survive but their ownership model allows them to sacrifice profits to do good

There is no panacea. BRAC will not work everywhere and markets can eat alive those who choose not to always prioritise profits. Family-owned and private companies can be the worst performers on sustainability and often lack the transparency and scrutiny imposed by stock markets. However, ownership is a key part of the DNA of a company and can enable or prevent inclusive and pro-poor business investments. There is scope to be more sophisticated in differentiating businesses and their impacts that can start with, but must go beyond ownership. We need to get a lot better at it.

April 7, 2015

How to get a job in development: the definitive (368 page) guide

How to get a job in aid and development? That is the question hovering over lecture theatres and seminar rooms everywhere,  as students rack up those debts and wonder if/how they will ever get a job which both fulfils them and keeps them solvent.

as students rack up those debts and wonder if/how they will ever get a job which both fulfils them and keeps them solvent.

Up until now, the only place to refer people has been long lists of links, a scatter of websites like Devex or AidBoard and random posts from people like me.

Now, there’s something much more substantial. This week, Routledge is publishing ‘Working in International Development and Humanitarian Assistance: A Career Guide’ by Maia Gedde, with a foreword by me. It’s 370 pages of invaluable material, but it costs $60 in paperback – maybe one for a library order?

The book provides a brief history of the aid business and explores some of the aspects that attract people to the sector (as well as the common concerns). Then it gets into the nitty gritty – how to ‘break into the sector’ (routes, qualifications, volunteering, job searches and interviews); career development; working as a consultant or starting your own NGO, ‘returning home’. Then a monumental typology of 54 different thematic areas, job functions or areas of expertise (impressed yet?), each with advice on the nature of the work, the main employers in the sector and what they will be looking for.

Here’s my foreword:

‘Reading Maia Gedde’s wonderful guide to working in international development brought home to me how lucky I am. And how old. I started working in development NGOs in the late 1990s, after a 20 year random walk involving a physics degree, backpacking, human rights activism, journalism, a Latin American thinktank and a spell keeping London nuclear free. Things are a bit better organized now – I probably wouldn’t give the younger me a job.

The aid business has professionalized over the last few decades: aid agencies have grown enormously in size and sophistication, with a rise in specialization (humanitarian emergencies, advocacy and campaigns, long term development, new academic disciplines). It has internationalized, with the old domination by ‘white men in shorts’ giving way to a much more global intake of personnel. And it has prompted a boom in students seeking qualifications and ways to find that cherished job where you can get paid (a bit) for changing the world.

But that is where international development has so far failed. It has not put in place the kind of entry schemes (graduate entry, sponsored degrees, professional qualifications etc) and career ladders that other, more established professions have introduced.

In part, I am glad – there is something about making development too slick, too much of a formalised career that could undermine the political and moral basis for getting involved in the first place. Excessive professionalization could exacerbate the current tendency to try and distil development into an apolitical technocratic exercise, when the reality, whether a country or community prospers or languishes is determined above all by issues of power and political struggle.

But even if a conveyor belt from university to country director might be a bad idea, it is still worth helping those desperate to get a foot on the ladder before they become disillusioned and drift off to other destinies, and this book makes a real contribution. Not only does it chart the full range of potential jobs and their concomitant lifestyles, but it illustrates it with hundreds of quotes from the men and women who are currently doing them – the whole aid business becomes humanized along the way. Gedde helps the reader sift through the options, finding those that most fit their character and expectations. She even throws in a handy dummy’s guide to theory and practice in development.

But even if a conveyor belt from university to country director might be a bad idea, it is still worth helping those desperate to get a foot on the ladder before they become disillusioned and drift off to other destinies, and this book makes a real contribution. Not only does it chart the full range of potential jobs and their concomitant lifestyles, but it illustrates it with hundreds of quotes from the men and women who are currently doing them – the whole aid business becomes humanized along the way. Gedde helps the reader sift through the options, finding those that most fit their character and expectations. She even throws in a handy dummy’s guide to theory and practice in development.

For years, I have felt a slight twinge of guilt at the inadequacy of the advice I have dispensed to bright eyed graduates asking how they can get a start in the aid business. Now I know exactly what to recommend, and for that, I am very grateful.’

And the Guardian’s also running an extract from the book today.

April 6, 2015

Links I Liked

Really horrible. Photo of 4-yr-old Syrian girl surrendering to a camera’s telephoto lens is real, not faked

Tourism: the world’s largest industry. One in every 11 jobs worldwide; 9.5% of global GDP. Yet of every $100 spent by an average developed-world tourist, only $5 remains in the destination’s economy [h/t Erinch Sahan]

What the climate movement must learn from religion: creating ‘altar calls’, conversion, witness, epiphany. And numbers: 40,000 people = London’s largest ever climate march, but 2 million attended UK Churches on Easter Sunday.

What happens when you let ‘experts’ tweak your draft SDGs/ post 2015 targets? They get worse.

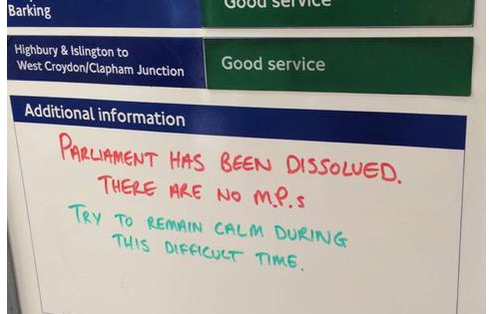

UK elections: Whoever gave the green light for humour on London’s tube deserves our gratitude [h/t Diane Abbott]. And here’s 8 more top tube signs.

UK elections: Whoever gave the green light for humour on London’s tube deserves our gratitude [h/t Diane Abbott]. And here’s 8 more top tube signs.

Time for some pessimism on governance:

Democracy behind bars: 11 opposition leaders facing jail or death

For the next few years, the richer Africa gets, the less democratic it will become [h/t Rakesh Rajani]

Submit all-male panels for David Hasselhof treatment. Funny & sharp campaign [h/t Heather Marquette] And hardly anyone has signed up to Owen Barder’s pledge not to sit on one – come on guys!

April 1, 2015

Why we should be worried by the World Bank shoveling $36bn to ‘financial intermediaries’

Everyone’s heard of the World Bank, but far fewer people know of its private sector arm, the International

Look on our logos ye mighty, and despair!

Finance Corporation, which describes itself as ‘the largest global development institution focused exclusively on the private sector in developing countries’. It’s huge and growing, and it’s got some nasty skeletons in its cupboard – today it comes in for a good kicking from The Suffering of Others, a report by a logotastic coalition of 12 NGOs, including Oxfam, ahead of the World Bank Group Spring Meetings.

Nearly two thirds of the IFC’s lending goes to the financial sector, mainly to ‘financial intermediaries’ (FIs), including commercial banks, private equity and hedge funds.

Now there’s no question that poor countries and people need access to finance: access to financial services and private finance plays a critical role in economic and social development, and is often sorely lacking. The trouble arises because the IFC is shovelling billions into FIs in a ‘hands off’ strategy that has led to some spectacular own goals – the report brings together some horrific case studies of the social and environmental impact of these loans, including rubber, sugarcane and palm oil plantations in Cambodia, Laos and Honduras, a dam in Guatemala and a power plant in India. Other risky projects include yet more power plants and dams in West Papua, Laos and Guatemala, a mine in Vietnam, and sugar plantations in Guatemala.

In the words of one community representative from Cambodia, ‘We want the World Bank to know that its money is being used to destroy our way of life. Nowadays, we are surrounded by companies. They have taken our community lands and forests. Soon we fear there will be no more land left for us at all and we will lose our identity. Does the World Bank think this is development?’

That Cambodian community and a number of others have taken complaints to the World Bank’s Compliance Adviser/Ombudsman (CAO), and the IFC has promised to shape up, but the report argues that it has made nowhere near enough progress to date.

Anti-dam protest by indigenous people, Guatemala

In addition to the direct impact in destroying the lives of poor communities, this matters for at least two further reasons – the IFC is increasing its exposure in fragile states (where safeguards and rule of law are particularly absent) by 50 per cent, and lots of other big lenders are jumping on the FI bandwagon, from the Brazilian development bank BNDES and the European Investment Bank, to the Green Climate Fund and the new Global Infrastructure Facility.

I started to think about the report from a systems perspective: if financial lending takes place in a complex system, then it is impossible to predict the impact of any given loan in advance – demanding total prior knowledge of impact is effectively saying you are opposed to all loans. The report doesn’t say that – what it mainly argues for is much better systems of transparency, feedback and self correction, which is just what you need in a complex system. Currently, the IFC is falling way short on all three. For example, how can feedback systems work when in 94% of the IFC’s highest risk investments in the last two years, there is no information publicly available about where the investment has ended up on the ground?

But if it can get the right combination of as good an ex ante risk assessment as possible, coupled with proper feedback loops and response mechanisms, it could provide a useful model for others.

Last year on this blog, Peter Chowla explored the choices facing civil society organizations on this shift towards the use of FIs – definitely worth another read:

‘Success stories, such as Korea, Taiwan and China, relied on a heavily regulated domestic financial sector that supported

The wrong kind of financial intermediary

industry. The IFC doesn’t seem to have this in mind, but instead prioritises “financial deepening” and “financial inclusion”, as fuzzy as any concepts in the development lexicon.’

Peter set out ‘three possible approaches civil society could take: asking for stronger rules and transparency; investing in ‘better’ private financial institutions; or throwing it all out the window and demanding public (not private) sector finance.’ This report seems to be going for the first.

March 31, 2015

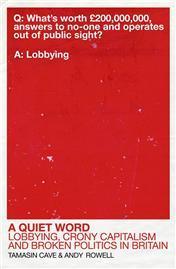

Advocacy and Lobbying: What Can We Learn from the Bad Guys?

A colleague of mine who shall be nameless (you know who you are Max), urges his fellow campaigners to ‘learn from the

enemy’ – Machiavelli, Friedman, Big Tobacco, you get the picture. A new book by Tamasin Cave and Andy Rowell may help. A Quiet Word: Lobbying, Crony Capitalism and Broken Politics in Britain has lessons for activism stretching well beyond our borders. The authors summarized their ’10 lessons’ in a recent Guardian piece. I’ve cut it down a bit, and added some commentary about the relevance to aid and development organizations in italics.

‘Lobbyists are the paid persuaders whose job it is to influence the decisions of government. Lobbyists operate in the shadows – deliberately. As one lobbyist notes: “The influence of lobbyists increases when it goes largely unnoticed by the public.”

[Tricky for aid and development types committed both to transparency and inclusion of the people whose voice is normally ignored – see post on the Dark Arts of advocacy]

Here are 10 key steps that lobbying businesses follow to bend government to their will.

1. Control the ground

Lobbyists succeed by owning the terms of debate, steering conversations away from those they can’t win and on to those they can. If a public discussion on a company’s environmental impact is unwelcome, lobbyists will push instead to have a debate on the hypothetical economic benefits of their ambitions. Once this narrowly framed conversation becomes dominant, dissenting voices will appear marginal and irrelevant.

[Yep, I’m still trying to learn to not answer the question in interviews, but get back to the basic framing discussions instead]

2. Spin the media

The trick is in knowing when to use the press and when to avoid it. The more noise there is, the less control lobbyists have. As a way of talking to government, though, the media is crucial.

[And to fix it when things go wrong. In the UK] Private healthcare regrouped after the wrong messages went public. As Andrew Lansley embarked on his radical reforms of the NHS, private hospitals and outsourcing firms were talking to investors about the “clear opportunities” to profit from the changes. Mark Britnell, the head of health at accountancy giants KPMG and a former adviser of David Cameron, hit the headlines in May 2011, telling an investors’ conference that “the NHS will be shown no mercy and the best time to take advantage of this will be in the next couple of years.” The industry got a grip. Lobby group The NHS Partners Network moved quickly to get everyone back on-message and singing from “common hymn sheets”, as its chief lobbyist David Worskett explained. The reforms were about the survival of the NHS in straitened times. Just nobody mention the bumper profits.

[And to fix it when things go wrong. In the UK] Private healthcare regrouped after the wrong messages went public. As Andrew Lansley embarked on his radical reforms of the NHS, private hospitals and outsourcing firms were talking to investors about the “clear opportunities” to profit from the changes. Mark Britnell, the head of health at accountancy giants KPMG and a former adviser of David Cameron, hit the headlines in May 2011, telling an investors’ conference that “the NHS will be shown no mercy and the best time to take advantage of this will be in the next couple of years.” The industry got a grip. Lobby group The NHS Partners Network moved quickly to get everyone back on-message and singing from “common hymn sheets”, as its chief lobbyist David Worskett explained. The reforms were about the survival of the NHS in straitened times. Just nobody mention the bumper profits.

[Aid agencies are generally savvy media operators, provided they stick to their broader mission and don’t get too hung up on their own survival]

3. Engineer a following

It doesn’t help if a corporation is the only one making the case to government. That looks like special pleading. What is needed is a critical mass of voices singing to its tune. This can be engineered. The forte of lobbying firm Westbourne is in mobilising voices behind its clients. Thirty economists, for example, signed a letter to the FT in 2011 in support of the High Speed 2 rail link; 100 businesses endorsed another published in the Daily Telegraph.

[Building broad alliances is a standard NGO tactic, and they don’t have to be bought – economists and others will happily sign up if your argument is sound]

4. Buy in credibility

Corporations are one of the least credible sources of information for the public. What they need, therefore, are authentic, seemingly independent people to carry their message for them.

One nuclear lobbyist admitted it spread messages “via third-party opinion because the public would be suspicious if we started ramming pro-nuclear messages down their throats”. The tobacco companies are pioneers of this technique. Their recent campaign against plain packaging has seen them fund newsagents to push the economic case against the policy and encourage trading standards officers to lobby their MPs. British American Tobacco also currently funds the Common Sense Alliance, which is fronted by two ex-policemen and campaigns against “irrational” regulation.

[We don’t always pay enough attention to getting the messenger right as well as the message – decision makers will often listen to a captain of industry, Archbishop or a Nobel laureate, when they would ignore campaigners]

5. Sponsor a thinktank

“The thinktank route is a very good one,” said ex-minister Patricia Hewitt to undercover reporters seeking lobbying advice.

Documents from Philip Morris reveal that the leading neo-liberal thinktank, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) is one of its “media messengers” in its anti- plain-packaging campaign.

[We work closely with lots of thinktanks as partners, but most of the time can’t afford to actually hire them – they cost a bomb]

6. Consult your critics

Companies faced with a development that has drawn the ire of a local community will often engage lobbyists to run a public consultation exercise. Again, not as benign as it sounds. “Businesses have to be able to predict risk and gain intelligence on potential problems,” says ex-Tesco lobbyist Bernard Hughes. “The army used to call it reconnaissance; we call it consultation.”

[Not so relevant, but the Tesco quote is a gem]

7. Neutralise the opposition

Lobbyists see their battles with opposition activists as “guerrilla warfare”. They want government to listen to their message, but ignore counter arguments coming from campaigners.

Lobbyists have developed a sliding scale of tactics to neutralise such a threat. Monitoring of opposition groups is common: one lobbyist from agency Edelman talks of the need for “360-degree monitoring” of the internet, complete with online “listening posts … so they can pick up the first warning signals” of activist activity. Rebuttal campaigns are frequently employed: “exhausting, but crucial,” says Westbourne.

Lobbyists have also long employed divide-and-rule tactics. One Shell strategy proposed to “differentiate interest groups into friends and foes”, building relationships with the former, while making it “more difficult for hardcore campaigners to sustain their campaigns”. Philip Morris’s covert 10-year strategy, codenamed Project Sunrise, intended to “drive a wedge between various anti groups” and “position antis as extremists”.

[We certainly understand the need to identify ‘leaders and laggards’ in any given sector and work with the former to overcome the latter. But I don’t think we’re good enough at rapid rebuttal or picking up early signals of new anti-development threats, though – we usually wait til they bite us before reacting]

8. Control the web

Today’s world is a digital democracy, say lobbyists. Gone are the old certainties of how decisions were made “by having lunch with an MP, or taking a journalist out,” laments one. It presents a challenge, but not an insurmountable one.

so become one….

One key way to control information online is to flood the web. Lobbying agencies create phoney blogs for clients and press releases that no journalist will read – all positive content that fools search engines into pushing the dummy content above the negative, driving the output of critics down Google rankings. Relying on the fact that few of us regularly click beyond the first page of search results, lobbyists make negative content “disappear”.

Another means of restricting access to information is the doctoring of Wikipedia, “a ridiculous organisation,” in veteran lobbyist Tim Bell’s words.

[I really hope no NGOs or campaigners are doing this]

9. Open the door

Access to politicians can be bought. It is not a cash deal, rather an investment is made in the relationship. Lobbyists build trust, offer help and accept favours. The best way to shortcut the process of relationship-building is to hire politicians’ friends, in the form of ex-employees or colleagues.

[Well we certainly employ a few parliamentary and political lobbyists, but they don’t have cheque books to wave around. Instead we rely on building relationships the hard way.]

10. And finally …

There is the perception, at least, that decisions taken in government could be influenced by the reward of future employment. The department that sees more movement than any other is still the Ministry of Defence. Since 1996, officials and military officers have taken up more than 3,500 jobs in arms and defence related companies.

[Just can’t see offering jobs in Oxfam as a major incentive......]

But I see plenty missing from this list:

The importance of seizing the windows of opportunity provided by shocks (disasters, crises and scandals), as Naomi Klein has brilliantly shown.

Find yourself a (very) rich backer – The Koch brothers have probably done more to undermine the climate movement than anyone else (but I guess this is easier for the bad guys, right?)

If you’re thinking long term, better to hire a university than a thinktank. In the 1950s at the University of Chicago, Hayek, Friedman and Harberger were busily nurturing the neoliberal flame when all about them was Keynesianism or worse. They set up a scholarship system with Chile’s Catholic University in 1955, taking their bright young things for some serious brainwashing. 20 years later the ‘Chicago Boys’ provided the hatchet men for General Pinochet’s economic policy – now that’s what I call a long game.

Other suggestions?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers