Duncan Green's Blog, page 166

April 29, 2015

How can grassroots aid programmes influence the wider system?

In the first of two posts on how aid agencies can use their grassroots work to exert wider influence, Erinch Sahan discusses his  work with livelihoods programmes (jobs, incomes etc). Tomorrow, I’ll discuss the conditions for such ‘joined-up influencing’ to work.

work with livelihoods programmes (jobs, incomes etc). Tomorrow, I’ll discuss the conditions for such ‘joined-up influencing’ to work.

“Give someone a fish and you feed them for a day; teach someone to fish and you feed them for a lifetime.” Sounds comfortingly intuitive, right? But what if people can’t access the water or afford the boats? What if fish stocks are disappearing or pollution is making the fish unsafe to eat? Or cultural norms dictate that women aren’t allowed to fish? For decades, NGOs and aid agencies have tried to lift people out of poverty through their version of “teaching someone to fish” – but this hasn’t been enough.

That’s where influencing comes in. The programmes we operate and the people we hope to help operate in complex and overlapping systems: political, economic, legal, household, community and natural systems, just to name a few. If we can influence how these systems work so that power is shifted to the powerless, we can then start seeing broader impact. This means influencing the ‘rules of the game‘ so that they protect fish stocks, give fair access to water, break down gender discrimination and allow fisher-people to bargain for cheaper boats (to stick with the fishing analogy).

Beekeepers in Ethiopia

But where to start when programmes are geared mostly to deliver on the log-frames that drive them forward and rarely have the flexibility for the fluid game-playing associated with influencing?

Recently, I’ve been working with Oxfam’s two flagship enterprise and markets programmes (the Enterprise Development Programme (EDP) and the Gendered Enterprise and Markets Programme (GEM)) on this. Here are four lessons I’ve learned the hard way for shaping how we’re building the influencing components of our enterprise and markets programmes in countries:

1. Start by scrutinising the problem, not with a tactic

If I had to pick one lesson, I’d say clarity about the problem we want to address. Clarity allows us to zoom in on the right decision-makers and decision-making processes (formal and informal). Once that’s clear, the power analysis begins, where we unpack the ways these decisions can be influenced and the tactics that we should deploy (ranging from writing a research report to public campaigning, from joint-lobbying with companies to convening workshops to highlight farmer perspectives to officials).

Unfortunately, I’ve seen too many aspiring advocates start with the tactic (“let’s do some research to convince MPs of our position”) before really understanding the problem. Only then can you break down who needs to be influenced (maybe not the MP – maybe it’s a business leader at the helm of an industry association or an advisor in the president’s office?).

The very last step is to decide the tactics, which build on what will influence the target (e.g. media attention, collective voice

Women dairy farmers, Bangladesh

of farmers, evidence of business support for the measure, evidence of likely positive impacts) [extra tip: rarely does evidence convince politicians].

2. Don’t get walled in by your laundry-list of problems

You will almost certainly have a long list of problems you can rattle off. Ask a programme office working on agriculture, and they’ll probably highlight: access to finance, lack of economic opportunities for women, access to extension, lack of lead firms committing to sourcing….. We need to pick and choose, but prioritising can be painful, so I ask four questions:

(1) Is it important to the people and enterprises we want to help?

(2) Are we (and allies) well placed to focus on this issue (i.e. do we have the right expertise, programme evidence, networks, credibility etc)?

(3) Is there an external opportunity to influence (i.e.; is there a reform process, market disruption, increasing public interest etc)?

(4) Is there energy on this (are others already working on influencing on this)?

If the answer is “no” to any of these questions, we probably shouldn’t be focusing our influencing efforts on it.

3. Ensure programme officers make time for meeting thought-leaders

Programme staff often lack the confidence to engage on bigger picture policy debates. But when they do, their perspectives are thoroughly grounded in programme experience. This makes them credible and means they’re bringing fresh and unique perspectives to policy debates. Giving time to programme staff to ensure they’re engaging in conversations with industry organisations, think-tanks and policy-makers will help get the influencing juices flowing and help them spot influencing opportunities. They’ll have more to contribute than they realise.

4. Avoid the stereo-type that influencing only equates to lobbying governments

Policy-making is only one possible area to influence. Ditto with national-level focus, as our energy may be best spent at local level. For instance, if communities are unable to access agricultural extension, the solution may not lie in achieving formal policy change, it might be about influencing the attitudes of extension officers. Ensuring time-saving tools are available to women farmers may not be about getting government investment in relevant R&D, but might be about working with farmers to demonstrate the market opportunities to agricultural tool manufacturers who are looking to expand.

Policy-making is only one possible area to influence. Ditto with national-level focus, as our energy may be best spent at local level. For instance, if communities are unable to access agricultural extension, the solution may not lie in achieving formal policy change, it might be about influencing the attitudes of extension officers. Ensuring time-saving tools are available to women farmers may not be about getting government investment in relevant R&D, but might be about working with farmers to demonstrate the market opportunities to agricultural tool manufacturers who are looking to expand.

Influencing is more of an art than a science. It means we need to keep looking at how the systems and associated power are shifting. It means we need to keep looking for opportunities to influence as success usually capitalises on new opportunities. Programmes can be great vehicles for influencing decisions and attitudes beyond their territory and we must enable them to do so.

April 28, 2015

Political (and some other) priorities in Nepal as of 28 April 2015

Reflections from Kathmandu by John Bevan, a friend and former UN official who has worked in Haiti – before and after the 2010  quake, as well as Nepal (2003/4 and 2006/7). This piece does not represent Oxfam’s official views, but offers a fascinating insight into what is likely to happen next.

quake, as well as Nepal (2003/4 and 2006/7). This piece does not represent Oxfam’s official views, but offers a fascinating insight into what is likely to happen next.

Today is day four of the emergency and the search and rescue period, at least in Kathmandu, is past its peak. Yesterday I went to the minaret style lookout tourist tower where quite a few people died—there was no sign of anyone still doing search and rescue, SandR as we know it here. Clearly there has been little, probably no SandR in rural areas where it is most needed and few rapid assessments.

My personal assessment is that in Kathmandu the damage has been cruel but relatively limited compared to the devastation of Port au Prince in 2010, which of course is not a very useful reference point as it was such an exceptional event. Government figures suggest that almost half of the reported 6,000 victims are from the Kathmandu valley and maybe one or two of the most affected districts. It is not yet clear what the total toll is. It is unfortunate that the media have been concentrating on the dramatic impact on temples and other religious building as this gives a distorted image of the situation. Remarkably few modern, concrete, buildings have been affected in the capital. In the countryside, however, most buildings are old, made of mud or weak bricks and stand on vertiginous slopes. These are the remote hill villages which it would appear have borne the main brunt of the quake, at least according to government statements.

Immediate and medium-term priorities:

The immediate problem I see is the dearth of rapid assessments in the hill villages, on which of course all action and prioritization depends. To be fair, this is no easy task in this event as I understand that the fault is about 150 km long, in nice terrain for trekking but very difficult areas to track. I am told that this is the pre-planting season in the hills so there is an urgent need to support the peasants to avoid the loss of a whole season’s crop. This would obviously lead to great problems for these food-deficient smallholder farmers. An additional consequence could be an intensification of the already strong urban drift.

The immediate problem I see is the dearth of rapid assessments in the hill villages, on which of course all action and prioritization depends. To be fair, this is no easy task in this event as I understand that the fault is about 150 km long, in nice terrain for trekking but very difficult areas to track. I am told that this is the pre-planting season in the hills so there is an urgent need to support the peasants to avoid the loss of a whole season’s crop. This would obviously lead to great problems for these food-deficient smallholder farmers. An additional consequence could be an intensification of the already strong urban drift.

For reasons described below, an important measure in ensuring the relief and then reconstruction are effective, just and transparent is the involvement from the start of renowned figures from civil society with the credibility to provide trustworthy oversight of the use of funds—this cannot be left to a conclave of state officials and their party bosses and colleagues.

Now is also the time to have a serious think about the medium-term. A single sentence characterization of the current political set-up in Nepal would be something like: high level of political party membership and influence with each party vying for power through support based on patronage networks, nepotism and cronyism in parties which are almost all led by traditional elites and their loyalty networks. Such political polarization and petty power struggles are antithetical to a decent reconstruction effort.

Mitigating measures are an essential and daunting task. Over the next one to two weeks, this involves:

Government of Nepal allowing neutral, reputed aid agencies with experience in first-response to travel freely and quickly, and combining their assessments with those of local government officials;

Donors reaching consensus on minimum standards both for oversight of government performance and in terms of their own transparency;

Government of Nepal defining clearly the movement and decisions of representatives of armed forces of other countries.

Beginning now and continuing on a regular basis:

Frank self-evaluation by donors of the integrity of their programmes over the last decade;

Avoiding the disastrous impact of the “All Party Mechanisms”, APMs, through which money was channeled at district level and below following the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in November 2006—it is well documented that these APMs (curiously close to ATMs!) were effectively a way of splitting funds between the parties with most local influence. They were officially ‘disbanded’ a few years ago though the practice of the political divvying up of state funds continues informally till now.

A careful comparison should be made of the aid disbursement mechanisms set up to ‘guarantee good governance’ with what  happened to donor funds post the January 2010 Haiti earthquake. It looked good on paper but was dogged by disputes, largely with Haitians feeling excluded and unheard. It did not survive the 2010/11 elections and change of government. It proved slow and clunky; financial oversight was so extreme that it effectively disabled the mechanism and even then there are many accusations of favouritism in the award of contracts.

happened to donor funds post the January 2010 Haiti earthquake. It looked good on paper but was dogged by disputes, largely with Haitians feeling excluded and unheard. It did not survive the 2010/11 elections and change of government. It proved slow and clunky; financial oversight was so extreme that it effectively disabled the mechanism and even then there are many accusations of favouritism in the award of contracts.

Big-picture, systemic challenges:

This is the context, which is easier to describe than to remedy. At this point, maintaining “systems” and doing “business as usual”, but just a bit faster and better, are seen as massive net positives, demonstrating to the population that the bureaucracy and state are still running etc. It is debatable if they demonstrate any such thing – anger is already building in parts of Kathmandu and in some hill villages which it has been possible to contact, where populations feel ignored, feel that there IS no government they can see, to say nothing of the very badly affected districts, from where the true picture has barely begun emerging– but the urge, in the name of strategic planning, is to huddle, reinforce old behaviours and say that emergencies are not the time for reform.

One key factor is the conflation of the term ‘independent’ with the term ‘all party’.

Donors should be aware that broad party involvement should not be confused with representativeness. Exemplary of this is the naming by the political parties of place-people to statutory bodies including the national human rights commission and the recently-named Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This way of negotiating political patronage networks and influence leads to a discrediting of such bodies, which are not perceived as legitimate or independent, given how often candidates are perceived to be named as a political reward rather than on merit.

Coordination of the multiplicity of relief efforts is essential, as is not weakening the government further, ensuring lack of duplication and parity of coverage, streamlining operations etc. But this cannot be conflated with what have become policy positions for the Finance and Home Ministries: to exert full Government of Nepal control, with all the implications spelled out above, over all national and international funding; and to attempt to micro manage what international agencies can do, and where and when they can do it, again with all the implications spelled out above and below for patronage, graft and inefficient and unfairly balanced reconstruction efforts.

April 27, 2015

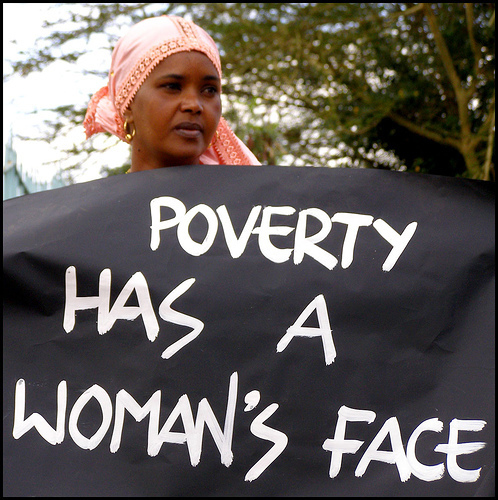

Could the UN’s new Progress of the World’s Women provide the foundations for feminist economic policy?

Yesterday I went to the London launch of UN Women’s new flagship report, Progress of the World’s Women 2015-16, in the  slightly incongruous setting of the Institution of Civil Engineers – walls adorned with portraits of bewigged old patriarchs from a (happily) bygone era (right).

slightly incongruous setting of the Institution of Civil Engineers – walls adorned with portraits of bewigged old patriarchs from a (happily) bygone era (right).

The report is excellent. These big multilateral publications are usually a work of synthesis, bringing together existing research rather than breaking new ground. And that’s fine; it’s really important that a UN body has pulled such an excellent range of research together and made it accessible to policy makers. Gender and development debates suffer from a fair number of unsubstantiated claims and pretty dodgy stats (don’t get me started), and this report feels like something you can trust – I hope someone will go through it and pull out every major stat and graphic.

But the overall approach is both new and exciting, in that it applies an explicitly human rights approach to economic policy. Laura Turquet, UN Women researcher and report manager, summarized this as ‘bringing together human rights and economic policy-making to ask ‘what is the economy for?’’

This is a big deal, because the normal approach to gender and economic policy is incredibly reductive and instrumental – educate girls and get women into the workforce because it boosts growth! It ignores whether that will improve the lives of the said women or just pile more burdens onto their pre-existing roles as carers (of children, old people, neighbours), home maintainers etc etc.

Running economic policy through a human rights filter produces 3 priorities:

decent work

social policies (including the care economy)

an enabling macro-economic environment

According to Laura: ‘Social policies are traditionally seen as a sticking plaster to correct the failings of the economic system. This report says they need to work in tandem. Unpaid care work holds the two together.’

According to Laura: ‘Social policies are traditionally seen as a sticking plaster to correct the failings of the economic system. This report says they need to work in tandem. Unpaid care work holds the two together.’

At the launch UN Women Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka argued for ending the ‘care penalty’ that women face, by introducing complementary, supportive public policies. She also highlighted the blurred boundaries of the care economy: 65% of women in family businesses get no salary because their contribution is seen as a ‘twilight extension’ of care work.

The ‘enabling environment’ is the most original of the three bullets, and the hardest to get your head around. According to the Exec Sum:

‘Because macroeconomic policy is treated as ‘gender-neutral’ it has, to date, failed to support the achievement of substantive equality for women. From a human rights perspective, macroeconomic policy needs to pursue a broad set of social objectives that would mean expanding the targets of monetary policy to include the creation of decent work, mobilizing resources to enable investments in social services and transfers and creating channels for meaningful participation by civil society organizations, including women’s movements, in macroeconomic decision-making.

Conventional monetary policy typically has one target—inflation reduction—and a narrow set of policy tools for achieving it. However, there are other policy options: in the wake of the 2008 crisis, many central banks changed their approach to monetary policy by stimulating real economic activity to protect jobs rather than focusing exclusively on reducing inflation. In the arena of fiscal policy, countries can raise resources for gender-sensitive social protection and social services by enforcing existing tax obligations, reprioritizing expenditure and expanding the overall tax base, as well as through international borrowing and development assistance.’

Some initiatives can tick all 3 boxes and make a difference – worth scanning the smorgasbord of post-2015 agenda items and seeing which could simultaneous generate decent jobs for women and alleviate the pressures on the care economy. One such example would be early childhood care – shown to boost long term productivity and health, but also (done right) a path for women to professionalize their skills and have better paid, decent jobs (as well as a way to look after their kids).

Which all got me thinking. Swedish foreign minister Margot Wallström recently made headlines with her version of a feminist foreign policy. Does this report pave the way to a feminist economic policy that goes beyond the standard broad-brush critiques (e.g. we are measuring the wrong things and ignoring the care economy)? Could we see a feminist running commentary on the economic issues of the day – Grexit, the TPP, quantitative easing? How would it be different from a left-wing commentary (with which it has large areas of overlap)? I suggested to Laura that she runs the relevant chapters past some of the big heterodox economists (Dani Rodrik, Ha-Joon Chang etc) and ask for their views. She also has an open invitation to have a go on this blog.

Here’s the report’s infographic summarizing a rights-based approach to the macro-economy. It’s busy but repays scrutiny (if you can read it, if not you can download it here PoWW poster_info4_PRINT).

Here’s the Guardian’s review of the report. What else struck people about the report?

April 26, 2015

Links I Liked

Europe’s migrant shame – a cartoon because words can’t suffice [h/t Alex Evans and Shulem Stern]

The ups & downs of Sweden’s ‘feminist foreign policy’

UKIP and the public debate on UK aid

My life has changed completely: Yemeni Oxfam programme officer describes his family’s flight from the capital, fear and the daily grind.

10 tricks to appear smart in meetings. No 6: will this scale?

Lee Kuan Yew was an outlier. Authoritarianism is almost always worse than democracy on corruption

Brain Drain? It’s not that simple. A half of African-born doctors are trained outside their country of birth.15% of all doctors trained in Africa are born outside the continent.

What plane seating would look like, laid out on the basis of the U.S. income distribution

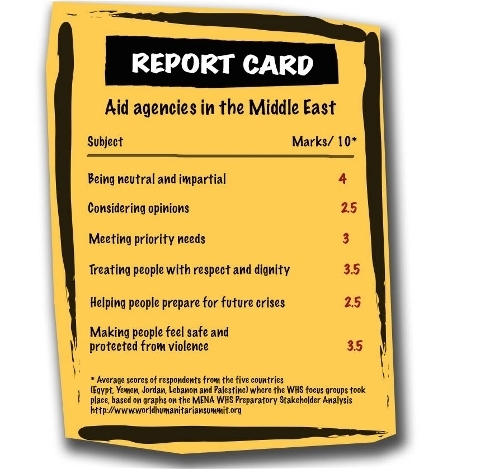

What do refugees in 5 Middle Eastern countries really think of aid agencies? Not much, apparently

April 23, 2015

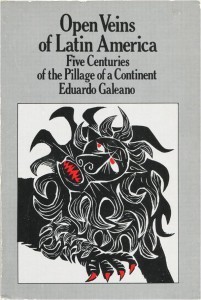

Here are some of the books that changed my life. What are yours?

I had a wonderfully self-indulgent day yesterday, spent in springtime Barcelona to give a talk on ‘the books that changed my

Saint George selling roses

life’, invited by ISGlobal, a health thinktank. The occasion was St George’s Day, when in Catalunya, the tradition is for men to give women a rose, and women give men a book. I know. Apparently the gender division has weakened a bit, with women getting books, but not many men get roses. Anyway, the streets of the city were were heaving with people and littered with stalls, bedecked in the red and yellow stripes of the Catalan flag, selling an astonishing variety of books and a lot of roses. Lovely. (St George is also a big deal in Ethiopia, by the way, as well as being England’s patron saint – anywhere else?)

For the talk, I decided to do the job properly, going back to childhood and really trying to think through which books influenced me. I heartily recommend the exercise – when he read it, my son announced that everyone should write their own. The biggest burst of nostalgia came from searching online for the original covers of the books for the accompanying powerpoint – some of which I hadn’t seen for decades. Here’s the full 3,000 word speech if you’re interested (The Books that Changed my Life), and the powerpoint of book covers (The Books that Changed My Life final).

A few general observations: first, let’s be honest – books have seldom ‘changed my life’ – nowhere near as much as people, school, jobs, life events, or probably even TV and film.

Second honest point: The books that have had the most profound impact tended to be the ones I read in my early years. I suspect this is a general truth – people’s deep world views and values are shaped more by what they read as children. If you want to really change the next generation, think JK Rowling, rather than Thomas Piketty.

Looking back over nearly 50 years of book-reading, I see a shape and a path of which I was previously rather unaware – the construction of that moral framework through child and teenager fiction, then in my early 20s a move from fiction to non-fiction, with the

recently departed Eduardo Galeano marking the moment of transition in my early 20s.

After that, non-fiction fleshed out that moral framework with people, issues and countries, first in Latin America, then everywhere. I moved through a series of disciplinary lenses – economics, history, anthropology, the lived reality of poor people, the salience of power, politics and systems, each adding new layers.

Books both created blind alleys and rescued me from the consequences (e.g the emotional

deserts of science fiction or excessive economism). Perhaps a low boredom threshold and contrarian tendencies has kept me from getting stuck and stopped me just reading to confirm existing opinions and approaches. As President Bartlett says in West Wing (which in recent years has influenced me at least as much as most books), ‘what’s next?’

And what of the students who yesterday were forced to sit through this massive exercise in Narcissism – will their paths be different? We discussed it a bit. They get their messages far more readily and in more variety these days – when they come to look back, it may be video games or box sets (maybe even blogs, but I doubt it) that they identify as their formative influences.

That busy-ness opens more routes to personal development, but perhaps blocks off some others – it’s hard to imagine kids today spending months studying a single novel, as I did with Ulysses or The Myth of Sisyphus when I was supposed to be studying physics. Or a poem like The Wasteland. Or taking refuge from the alienation of adolescence in multiple readings of Lord of the Rings. We are all twitchy with attention deficit these days – I wonder how that affects the way those deeper value frameworks form? Can blogs and twitter really provide a moral compass for life?

That busy-ness opens more routes to personal development, but perhaps blocks off some others – it’s hard to imagine kids today spending months studying a single novel, as I did with Ulysses or The Myth of Sisyphus when I was supposed to be studying physics. Or a poem like The Wasteland. Or taking refuge from the alienation of adolescence in multiple readings of Lord of the Rings. We are all twitchy with attention deficit these days – I wonder how that affects the way those deeper value frameworks form? Can blogs and twitter really provide a moral compass for life?

Over to you for comments on ‘if not books then what?’, and some honest revelations of the books that shaped you (and if you claim it’s Proust, I’ll assume you’re just trying to impress….)

April 22, 2015

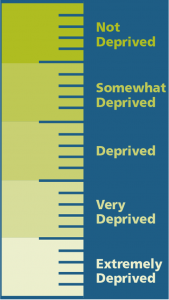

Lifting the lid on the household: A new way to measure individual deprivation

Guest post on an important new initiative from Scott Wisor, Joanne Crawford, Sharon Bessell and Janet Hunt

You don’t have to look far to find assertions that up to 70% of the world’s poor are women ‑ despite Duncan’s efforts to show

But how to measure it?

that the claim cannot be substantiated.

Just last month, ONE launched a new campaign called “Poverty is Sexist”, drawing on star power to bring attention to the issue of women’s poverty.

ONE didn’t use the 70% stat, but implied that poverty is feminized. Yet the reality is that it is still not possible to say whether women are disproportionately poor ‑ despite widespread calls for better sex-disaggregated statistics.

Why? Because both monetary measures of poverty such as the International Poverty Line and multidimensional measures such as the Multidimensional Poverty Index continue to use the household as the unit of analysis. This assumes that everyone in a given household is equally poor or not poor – and that’s a big problem.

Not to mention concerns about the gendered differences in the experience of poverty. How do you price the value of being free from violence or securely accessing family planning?

These are not small problems. A great deal hangs on how we measure social progress. Are development programs working? Do anti-poverty policies make a difference? Is foreign aid alleviating poverty? Evaluating households makes it impossible to see how different members of the household are doing. And failing to assess dimensions of life that are particularly important to poor women, or men, limits our ability to show whether and how their poverty differs.

So what to do? Well, despite heated debates about measuring global poverty, something of a consensus has emerged. Most experts now agree that monetary poverty measurement should be complemented by multidimensional measurements. The individual, not the household, should be the unit of analysis. Poverty measurement should reflect the views and priorities of poor people. And in so far as possible, measurement should provide meaningful comparisons across contexts and over time.

Seeing the individuals inside households matters

Enter the Individual Deprivation Measure. Five years ago, an international, interdisciplinary team led by the Australian National University set out to develop a genuinely gender-sensitive poverty measure. Working with poor women and men in Angola, Fiji, Indonesia, Malawi, Mozambique and the Philippines, we aimed to build from participants’ views to an internationally comparable measure of deprivation. We sought to bridge the gap between existing global measures determined without input from poor women and men, and highly localised poverty assessments that cannot be generalised.

In the first phase of participatory research, local research teams worked with poor men and women to determine how they conceived of poverty and hardship and how deprivation should be measured. In the second phase of research, participants told us which of the most commonly identified dimensions from Phase One were most important in determining whether a life was free from poverty and hardship.

From these findings, we constructed the Individual Deprivation Measure (IDM) and tested it in a nationally representative survey of 1800 people in the Philippines.

The IDM assesses the circumstances of individuals across 15 key dimensions of life. Within each dimension, the IDM  measures how deprived someone is on a 1 to 5 interval scale where 1 represents the most deprived (such as no improved water source, more than 30 minutes from home) and 5 represents a lack of deprivation (such as an improved water source in the home). So it tells us more about how difficult life is than existing monetary measures, which count whether a person is above or below a set line (say, $2 a day), and multidimensional poverty measures, which count whether a person falls below or above the threshold in a given dimension.

measures how deprived someone is on a 1 to 5 interval scale where 1 represents the most deprived (such as no improved water source, more than 30 minutes from home) and 5 represents a lack of deprivation (such as an improved water source in the home). So it tells us more about how difficult life is than existing monetary measures, which count whether a person is above or below a set line (say, $2 a day), and multidimensional poverty measures, which count whether a person falls below or above the threshold in a given dimension.

Poor women and men told us some deprivations were more significant than others, and weighting is used to reflect this. Within each dimension, we give greater weight to more severe deprivations (having no source of clean water counts for more than having one you can walk to). Across the dimensions, the 5 dimensions poor men and women ranked as most important for getting out of poverty are given more weight than the second five, and the second five more than the last 5. Weighting always creates debate, and there are certainly alternative methods of setting participatory weights. Importantly, our approach reflects participants’ views that improvement in your circumstances is more important the worse off you are, and some dimensions are more important than others.

How poor you are matters

An individual’s weighted score in each dimension is added up to give an overall IDM score. When we do this for all adult members of a household, we can evaluate how poverty varies based on gender, age, ethnicity or race, geographic location, or whether you live with disability. This enables tracking of horizontal inequalities. The IDM can also provide a gender equity measure more relevant to poor people than existing approaches, by calculating the gap between men’s and women’s achievements, overall or in particular dimensions, within a household or across the population.

There is still work to do in developing the IDM. But it is already a manifest improvement on current monetary and multidimensional measures, reflected in the strong interest at a recent side event at the Commission on the Status of Women. We expect interest to accelerate as results demonstrate what the IDM can reveal. Data from a national study of poverty in Fiji using the IDM will be available later this year, a proposal in Romania is pending decision and proponents in Costa Rica are seeking funding. The IDM has been adapted by the Ethical Research Institute for a multidimensional poverty study in Israel (results in Hebrew only now but English is coming). And a number of INGOs are interested in the IDM for baselines.

To know if no one is being left behind, we need to measure the poverty of individuals. The IDM makes this possible. The question now is whether governments and NGOs will get on with making poverty measurement reflect the true breadth, depth, and distribution of deprivation.

Acknowledgements: The research underpinning the IDM was led by the Australian National University and funded by the Australian Research Council (LP0989385), with significant additional support from International Women’s Development Agency, Oxfam Great Britain (Southern Africa), Oxfam America, Philippine Health and Social Science Association, the University of Colorado at Boulder and Oslo University. Huge thanks to local research teams and participants.

An edited version of this post also appears on the Guardian website

April 21, 2015

Scale, Failure, Replication and Gardening: Continuing the Discussion on the future of Big Aid.

Or should that be beautiful?

I’ve been having a series of great conversations on the draft of my new paper on the future of INGOs (plenty of time if you want to comment – here it is INGO futures, Green v5 April 2015 (edited)). Some of these have been under Chatham House Rules, so no names/organizations, but here are some of the standout topics that have emerged so far:

Scale: It’s all very well to ask ‘how do you take a supertanker white-water rafting?’ and suggest that big can be bad (slow moving, bogged down in procedures, conservative), but size also brings clear advantages. Scale creates influence, economies, cross-country learning and the ability to invest in experimentation and take more risks (even to pay the wages of weird strategic advisers bloggers who achieve nothing particularly tangible). Break up Oxfam into 40 mini-me’s and you would lose a lot, as well as potentially gain on flexibility and innovation.

So the question arises, what kind of hybrid combination of scale and subsidiarity gives you the optimal blend of flexibility and clout? And presumably that balance depends on the issue – economies of scale matter more in some areas than others – and the political and social context. The arguments are likely to look different depending on whether you are in long-term development, humanitarian or advocacy (see here for previous rant on Grey Panthers, aka rafts for wrinklies). Lots of thinking needed (as well as identifying what the current spread of supertankers and rafts is within the aid business and how well/badly it is working).

Finally, some versions of flotillas might be positively counter-productive – one cash-strapped Dutch NGO has apparently broken itself up into self-financing business units, with the predictable result that hard-to-fund areas like advocacy and development education have virtually disappeared.

Failure: There is a common lament that development failure is neither recognized nor punished- when was the last time an NGO went out of business? But the obvious difference is that companies go bust because there is a clear profit/loss bottom line, and very few non-commercial entities behave the same way (governments, UN bodies etc). And the noble efforts of Engineers Without Borders to get us all discussing and learning from failure seem rather to have, errm, failed.

Failure: There is a common lament that development failure is neither recognized nor punished- when was the last time an NGO went out of business? But the obvious difference is that companies go bust because there is a clear profit/loss bottom line, and very few non-commercial entities behave the same way (governments, UN bodies etc). And the noble efforts of Engineers Without Borders to get us all discussing and learning from failure seem rather to have, errm, failed.

So is failure the right way to think about performance or an unhelpful polarizing dichotomy when there isn’t a clear bottom line metric and in practice, almost any programme or change process is a combination of the two? Isn’t it more important to be able to identify elements within a programme that are not working and fix them en route, rather than reduce everything to binary red/green lights?

And there is a temporal issue here too. Development veterans who return to countries after long absences find that local staff in programmes that were once deemed ‘failures’ often turn up years later at the heart of success stories (a bit like Tim Harford’s Adapt thesis, or those failed infant industries that end up providing the basis for subsequent industrial take off).

Replication: We should acknowledge that there is already lots of one-off innovation going on. My colleague James Whitehead has been doing an internal positive deviance exercise, collecting and analysing dozens of innovations across our work – I’m trying to get him to write a post on it. I have long been

More replicants needed?

banging the drum for programmes like Chukua Hatua in Tanzania, and TajWSS in Tajikistan. But despite its success, Chukua Hatua is still the only Oxfam programme that I know of doing multiple parallel experiments. Why are such innovations not being replicated within/between agencies?

Ecosystem Gardening: If the UK is indeed a unique development cluster (as I argued in a recent post), then the role of big aid agencies (DFID, Oxfam) could be that of ecosystem gardeners, taking a system-wide view on nurturing and strengthening the cluster. This could include:

- More support for start-ups and spin-offs as incubators of new ideas/approaches – the sector is currently too much of a monoculture of generalist organizations all doing roughly the same thing.

- Encouraging large organizations to steal/borrow innovation from others

- Finding ways to overcome the ‘big money’ problem (large aid organizations with relatively few staff can only sign large cheques), eg through ecosystem intermediaries (who can break up large cheques into lots of small grants) or equity for spin-off organizations or ‘people not projects’ funds that back outstanding individuals.

- Encouraging greater complementarity – working in middle income countries is becoming politically difficult for northern governments (local governments resent the intrusion, taxpayers and the Daily Mail bang on about India’s space programme). Yet 60-70% of the world’s poor people still live in MICs. Perhaps bilateral agencies should consciously encourage a combination of national and international NGOs to pursue strategies tailored to MICs – eg norm change, tax, redistribution, innovation government policies and practices, etc

- Encouraging greater complementarity – working in middle income countries is becoming politically difficult for northern governments (local governments resent the intrusion, taxpayers and the Daily Mail bang on about India’s space programme). Yet 60-70% of the world’s poor people still live in MICs. Perhaps bilateral agencies should consciously encourage a combination of national and international NGOs to pursue strategies tailored to MICs – eg norm change, tax, redistribution, innovation government policies and practices, etc

- But also collaboration – there are some areas where the aid and development agencies are all engaged, but are not fully cooperating to learn vital lessons in what are really difficult operating environments eg on programming in fragile states; creating ‘safe spaces’ for discussion and learning from failure

Keep the comments coming please – this is all really useful.

April 20, 2015

Is a Data Revolution under way, and if so, who will benefit?

Guest post from the beach big Data Festival in Cartagena, Colombia, by Oxfam’s Head of Research and paid up member of the numerati, Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva (@rivefuentes)

A spectre is haunting the hallways of the international bureaucracy and national statistical offices – the spectre of the data revolution. Now, that might suggest a contradiction in terms or the butt of a joke – it’s hard to imagine a platoon of bespectacled statisticians with laptops and GIS devices toppling governments. But something important is indeed happening – let me try and convince you.

A new research report by ODI “Data Revolution – Finding The Missing Million” (LINK) (launched yesterday in Cartagena during a Data Festival) tries to make sense of the coming data revolution, and what it means for international development. According to the authors: The data revolution is “an explosion in the volume of data, the speed with which data are produced, the number of producers of data, the dissemination of data, and the range of things on which there are data, coming from new technologies such as mobile phones and the internet of things

and from other sources, such as qualitative data, citizen-generated data and perceptions data.”

For the numerically minded (I proudly include myself in this group) this is a rather welcome transformation. Data, data everywhere – but then why haven’t we, number geeks, solved all of the world’s problems yet?

This is where things get interesting in the report. There are two (for simplicity) main sources of statistics: official and alternative. They both present advantages and particular challenges.

Official development statistics are, for instance, rather expensive, infrequent and often miss the extremes of the distribution. The report indicates that, globally, as many as 350 million people are not covered by official household surveys – most of them either very rich or very poor.

This gap creates massive problems for the most basic of global statistics. Take global income poverty, for instance. According to Laurence Chandy from the Brookings Institution, the ‘fact’ that 25% of the people living in extreme poverty ($1.25 a day) are in sub-Saharan Africa – some 414 million people- is derived by extrapolating from household surveys dating from 2005 or earlier.

There are a lot of expectations about the potential of alternative sources, such as mobile phone generated data, but they are not without difficulties. The databases generated from these alternative sources are messy, often lack methodological consistency and require a lot of pruning and computing power to make basic sense of them.

But revolutions are supposed to be messy. One of the main challenges, the report argues, is the fight for space between official statistics and these alternative sources. This is, in a way, to be expected, as technological advances change the control of who generates statistics and how they’re used. There is some news that indicates that in Tanzania, for instance, the use of non-official statistics could even be

criminalized.

In short, the data revolution does have a political economy element. And its success will depend on whether official statisticians see the benefit of working together with the outside data scientists to learn better about the condition of a given country.

What are the opportunities to make use of these changes for the benefit of the poorest? There are two that I identify: how to use the increase availability of data for accountability and how to close the digital divide.

It won’t be easy though. There is hope that more information will automatically make governments at all levels more accountable but this seems naive. The report quotes Rakesh Rajani, formerly at Twaweza, an East African organization focusing on citizen accountability: “There are problems of power and agency – they are the largest challenges for use of data-feedback. Just having new data or ways of analysing doesn’t trump those constraints. If the government was non-responsive before, technology and data won’t solve the problem or suddenly turn it into more responsive. Data doesn’t assure you that voice will count”

Similarly, on the digital divide, the problem will not go away solely by improving data collection. The authors give an example in New Zealand relating to the Maori population: “Many Maori do not perceive themselves has having benefitted much from the data collection and use of data. They perceive a real and immediate risk of greater data availability being used for ethnic profiling to their detriment”

All this suggests that data availability and measurement innovation will not be enough. There is the need to for more data-driven active citizenship – or citizen engagement that make use of all this new information to promote inclusive policies and projects and ensure effective and appropriate use of resources. The report provides several examples of where this is happening already: Citizen-led poverty lines in Asia (much higher than the accepted $1.25 a day); Dwelling surveys used to negotiate resettlements in Mumbai; community organizations questioning the Ugandan government about the failure to meet commitments on health expenditure and increase health allocation, among others.

All this suggests that data availability and measurement innovation will not be enough. There is the need to for more data-driven active citizenship – or citizen engagement that make use of all this new information to promote inclusive policies and projects and ensure effective and appropriate use of resources. The report provides several examples of where this is happening already: Citizen-led poverty lines in Asia (much higher than the accepted $1.25 a day); Dwelling surveys used to negotiate resettlements in Mumbai; community organizations questioning the Ugandan government about the failure to meet commitments on health expenditure and increase health allocation, among others.

The report contains a lot more information and it’s hard to do justice to it on a blog (measuring poverty using roof materials as proxy, collected by satellite data? check; the rise of the Silicon Savannah in Kenya? check). It has a series of recommendations that seem obvious given the problems described – I found some of them, particularly the quick fixes, lacking in imagination. But overall the report is a very welcome piece – an easy, rather enjoyable read despite the seemingly esoteric topic.

So does this constitute a revolution or am I getting nerdily over-excited? I think new sources and, more importantly, effective use of this avalanche of data will turn many aspects of conventional government upside down, with huge potential to transform power and politics – if not ‘revolution’, what else would you call it?’

April 19, 2015

Links I Liked

China and the West: Not bad for a text written 113 years ago [h/t Branko Milanovic].

‘The road to development is paved with bad inventions’. Excellent Ben Ramalingam blog on Innovation

‘How to get governments and aid organizations to adapt to the good and throw out the bad?’ Chris Blattman riffs on a Dani Rodrik interview

States are actually responsible for a huge amount of tech innovation, but currently they socialize the risks, and privatize the rewards. What to do? Brilliant from Mariana Mazzucato

The World Bank breaks its own rules as 3.4 million people are forced off their land

UK election slot

The BBC’s Robert Peston asks if Labour Leader Ed Miliband is a game changer like Mrs Thatcher, repositioning Labour as the party of regulation (rather than increased welfare spending or state ownership)?

All journos should learn to ask questions like Reema, a year 7 pupil from Salford. Or else just give her the job [h/t Kirsty McNeill]

April 16, 2015

Sport can reach places where other aid and development programmes struggle. So why are we ignoring it?

Mel Paramasivan (@melparamasivan) says she was ‘that kid who was always picked last’. But now she is the Communications and Fundraising Manager at the Sport for Development charity International Inspiration, who are credited for all the pics in this piece.

Mel Paramasivan (@melparamasivan) says she was ‘that kid who was always picked last’. But now she is the Communications and Fundraising Manager at the Sport for Development charity International Inspiration, who are credited for all the pics in this piece.

“Oh, that’s nice” was the patronising response from another delegate at an international women’s rights conference when I explained how sport is being used to engage out of school girls in Kenya in financial literacy programmes. ‘Nice’ is how I would describe the canapé I was eating at the time, not the life-changing experiences of young women now in education, employment or training and finding alternatives to early marriage and motherhood.

The Sport for Development (S4D) sector remains a backwater within international development yet playing sport can overcome almost every discriminatory label and engage and sustain the attention of children and young people in settings less formal and intimidating than a four-walled classroom. Where other interventions fail, sport provides a platform for interactive learning – as when football was used as a way to teach young boys about the importance of girls’ rights and to teach young girls about their own rights. And that’s without mentioning the obvious direct benefits in healthy lives and well-being.

Sport does not leave people behind and as people with disabilities face the challenge of being included in mainstream development, sport can break cycles of exclusion and segregation. In the Bahir Dar region of Ethiopia, sport has enabled people with disabilities to take on responsibilities and leadership roles. Eighteen year old Taye Asfaw went from ‘observer to player’ when the Sport for Inclusive Development Programme was launched and is now managing the local youth centre. The partnership between S4D charity, International Inspiration (IN) and local community organisation the Leonard Cheshire Foundation is a trailblazing integration of sport into community-based programmes, so successful that the model is ready to be scaled up across the country.

Sport does not leave people behind and as people with disabilities face the challenge of being included in mainstream development, sport can break cycles of exclusion and segregation. In the Bahir Dar region of Ethiopia, sport has enabled people with disabilities to take on responsibilities and leadership roles. Eighteen year old Taye Asfaw went from ‘observer to player’ when the Sport for Inclusive Development Programme was launched and is now managing the local youth centre. The partnership between S4D charity, International Inspiration (IN) and local community organisation the Leonard Cheshire Foundation is a trailblazing integration of sport into community-based programmes, so successful that the model is ready to be scaled up across the country.

Sport is a second chance for those who have slipped through the cracks because of circumstances beyond their control and brings marginalised groups together to tackle the inequalities and injustices they face. Sport creates a special culture of unity and is omnipresent – you may not yet find clean water in every community in the world, but there will probably be a football match going on. So why has sport gone missing in development?

My colleagues have debated the issue extensively: how can sport become recognised in the SDGs? How can we get sport into the mainstream development agenda? What is the role of sport post-2015? My view is that sport will remain on the side-lines until the international development sector recognises the importance of culture and diversity.

Development culture’s stiff upper lip

Sport is a dramatic break from development tradition because it challenges conventional thinking that has largely excluded  culture. International development has been shaped by great minds, but so far, they have all come from the fields of economics and politics. There is more to life (and the lives of poor people) than that, which is where sport comes in. Sport symbolizes the kinds of power shift we need both within communities and in development. The scale of work undertaken by S4D organisations does not rival even the smallest UN body or INGO; instead organisations work autonomously and independently, understanding and addressing local challenges. In Kilifi, Kenya (the canapé story) sport has shifted power from local chiefs and community elders to young coaches and girls.

culture. International development has been shaped by great minds, but so far, they have all come from the fields of economics and politics. There is more to life (and the lives of poor people) than that, which is where sport comes in. Sport symbolizes the kinds of power shift we need both within communities and in development. The scale of work undertaken by S4D organisations does not rival even the smallest UN body or INGO; instead organisations work autonomously and independently, understanding and addressing local challenges. In Kilifi, Kenya (the canapé story) sport has shifted power from local chiefs and community elders to young coaches and girls.

Is sport just a middle-class distraction from the serious business of raising income levels and fighting for civil rights? To borrow from Bill Easterly – we need a little cynicism, sometimes – is S4D just a bunch of planners pursuing a grand vision of thousands of smiling children kicking around footballs? Absolutely not – it didn’t start with a UN bureaucrat with Development for All in one hand and a whistle in the other. The sector rose from the ground and has shifted, split and changed direction in twenty years of great contestation, of trial and error to develop models to work within existing structures that use sport and achieve development. Organisations like IN now look to move sport from an isolated intervention to being accepted as a mainstream development approach.

Sport is not the answer to everything (of course); sport is a means not an end. It is not a farming programme that directly produces food to address hunger, or an energy initiative to provide fuel, but it isn’t an afterthought either. There are, after all, lots of other development interventions that are more means- than ends- based.

Sport can also play a role in the bigger ‘grown-up’ stuff like political reconciliation and social cohesion – Lord Seb Coe argues it could help heal the wounds of the Paris attacks.

We’re all in this together

Sport has the potential to bring a strong and significant shift not only in development culture but how we talk about development and culture. The SDGs, like sport, come with a lot of jargon but at the heart of both are game changers and goals. To turn a blind eye and not offer a hand to sport is to ignore the kid on the side line, who could be a champion and inspire others. But we’ll never know unless we give them a chance.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers