Duncan Green's Blog, page 165

May 13, 2015

How do we get better at learning from history? Please help design a research programme.

Couple of tech glitches have delayed Jean Boulton’s response to yesterday’s post by Owen Barder, so here’s one I made earlier.

Why aren’t we more systematic in learning from history, when it comes to developmental success? Over a decade ago, Ha-Joon Chang  rocked the world of World Trade Organization delegates with ‘Kicking Away the Ladder’, which showed that the very infant industry policies that developing countries were being pushed to give up were at the heart of rich countries’ own take-off episodes. Recently, a few of us have started thinking through how to do the same thing on the politics of redistributive governments.

rocked the world of World Trade Organization delegates with ‘Kicking Away the Ladder’, which showed that the very infant industry policies that developing countries were being pushed to give up were at the heart of rich countries’ own take-off episodes. Recently, a few of us have started thinking through how to do the same thing on the politics of redistributive governments.

I’ve come across similarly useful ‘lessons of history’ exercises in other areas. A great study by Santosh Mehrotra and Richard Jolly on the role of the state in guaranteeing healthcare and education for all; Ha-Joon coordinated a great study for the FAO on agricultural policy in successful economies in Europe and elsewhere.

But why stop there? For example, how about:

Civil service reform: what have been the politics and economics of the shift to (more or less) meritocratic bureaucracies?

Environmental legislation: Back in the 1940s, my grandmother died in the London smog, what policies and institutions ensured that kind of thing no longer happens (or at least only rarely) in the UK and other rich economies?

Then there’s access to justice, reconstruction after conflicts, equal rights legislation, gender-based violence, financial sector regulation, competition policy, universal secondary education, curbing private and public sector corruption and so on.

For each of these, it would be interesting to look both at the now developed countries in Europe, North America etc, and the most successful among the developing countries since 1945, and see if any common patterns emerge (as Ha Joon found on both trade and agricultural policy).

For each of these, it would be interesting to look both at the now developed countries in Europe, North America etc, and the most successful among the developing countries since 1945, and see if any common patterns emerge (as Ha Joon found on both trade and agricultural policy).

I blogged about this back in 2011 and didn’t get much of a response, but I reckon it’s time to have another go, not least because I know someone who might be able to put some research funding into it.

One important question is identifying the ideal host institution – it has to tick at least four boxes: to be genuinely interested in history, to take a multi-disciplinary approach, to be socially progressive and to be academically credible.

This is a short post because I’m primarily looking for advice – what do you think of the idea? Which issues would you say are most likely to benefit from such an approach? And which institutional home would be most likely to work? Cambridge historian Simon Szreter reckons the History and Policy network might be a good place to start, so I may drop into their next seminar on 3 June to see what they are up to.

Over to you.

Update: And here’s me with a 3 minute pitch for the lessons of history project at a conference in February

May 12, 2015

Can aid agencies help systems fix themselves? The implications of complexity for development cooperation

Owen Barder gave a brilliant lecture on complexity and development to my LSE students earlier this year. Afterwards, I asked him to dig deeper into the ‘so whats’ for aid agencies. The result is this elegant essay (a bit long for a blog, but who cares?). I will try and get some responses to his arguments from similarly large brains.

on complexity and development to my LSE students earlier this year. Afterwards, I asked him to dig deeper into the ‘so whats’ for aid agencies. The result is this elegant essay (a bit long for a blog, but who cares?). I will try and get some responses to his arguments from similarly large brains.

If economic development is a property of a complex adaptive system, as I’ve argued elsewhere, then what, if anything, can development agencies and NGOs do to accelerate it?

To be clear what we mean when we say that development is a system property, here’s an example from the animal kingdom. You may have seen recently that ants have recently developed “super colonies” – including one that covers 6,000km along the Mediterranean that is said to be the largest co-operative unit in the animal kingdom. It is natural to talk about the “behaviour” of the colony, even though we understand that we are really talking about the individual actions of hundreds of millions of ants. Each ant responds to its external environment, including the behaviour of other ants. Because all the ants are adjusting to each other, this creates the sense that the colony as a whole is changing its behaviour, and we soon begin to ascribe intent and agency to the colony rather than the individual ants of which it consists.

Like any complex adaptive system, an ant colony will tend to go through long periods of stability and then sudden periods of rapid change that come about when ants all adjust their behaviour in response to changes in the behaviour of the ants around them. The emergence of a super-colony did not depend on the ants individually becoming fitter and stronger, learning new skills or becoming more entrepreneurial. They didn’t suddenly have access to better nutrients that made them healthier– nor have the ants benefited from universal education, access to microcredit, or new vaccines. In fact, the ants haven’t changed at all: the colony’s behaviour can change even if the individual ants have not, because it is a self-organising complex system whose behaviour in aggregate is not simply the sum of its parts: it is determined to a large extent by the way those parts interact with each other.

Like any complex adaptive system, an ant colony will tend to go through long periods of stability and then sudden periods of rapid change that come about when ants all adjust their behaviour in response to changes in the behaviour of the ants around them. The emergence of a super-colony did not depend on the ants individually becoming fitter and stronger, learning new skills or becoming more entrepreneurial. They didn’t suddenly have access to better nutrients that made them healthier– nor have the ants benefited from universal education, access to microcredit, or new vaccines. In fact, the ants haven’t changed at all: the colony’s behaviour can change even if the individual ants have not, because it is a self-organising complex system whose behaviour in aggregate is not simply the sum of its parts: it is determined to a large extent by the way those parts interact with each other.

There are plenty of other examples of complex systems in everyday life, such as the weather, our brains, and traffic. These systems have emergent properties which cannot be reduced to or predicted by characteristics of their component parts. Emergent properties such as thunderstorms, consciousness, and traffic jams are not brought about by changes in the characteristics of the systems components (air molecules, synapses, and cars) but by changes in the way these things interact

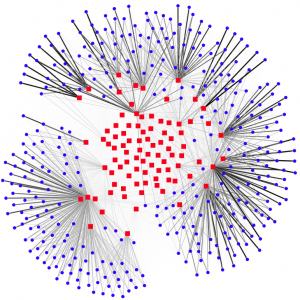

a very complex system

with each other. Emergent properties are characteristics of systems, not their components.

So what does this mean for development? An economic, political and social system develops when it evolves a complex, self-organised set of interlocking institutions that provide freedom, prosperity and opportunities to its people. Each of these individuals, groups or institutions acts within the constraints and authorising environment provided by the other parts of the system, and as these different parts of the system adapt to each other, so they co-evolve.

For example, an effective civil society depends not only on the resources of Civil Society Organizations themselves, but on the authorising environment and constraints of courts, media, political system, police, army, churches, business and the public. Effective firms depend on being able to interact with other firms, the maintenance of contestability and competition, and both the support and constraints of government, the courts, civil society, the workforce, unions, consumers and others. And effective government depends on firms, civil society, political institutions, media, law enforcement, courts and so on. These institutions simultaneously reflect and shape the distribution of power within society.

As these institutions all evolve, and interact with each other in ways that shape each other’s behaviour, so self-organising complexity begins to generate the freedoms, opportunities and prosperity that we call development. Development is a property of the system, not of its components. All of these institutions have to evolve together: trying to move any one of them individually into a “developed” state is unlikely to be sustained: that component will simply revert to the trajectory that is consistent with the opportunities and constraints provided by the rest of the system.

If you see development as the sum of its parts, then you might think we should work out which constraint binds the most tightly and invest resources to relax it. But if you see development as property of a complex adaptive system, then targeting a specific constraint is unlikely to “make development happen.”

So what does this mean for those of us who want to see development accelerated?

Let us first say what it doesn’t mean.

First, complexity does not condemn us to fatalism: there is plenty we can do to accelerate and shape the evolution of the system.

Second, better analysis is not the solution to complexity: the way to find out what works is through iteration and improvement, not decade-long research projects to understand it better.

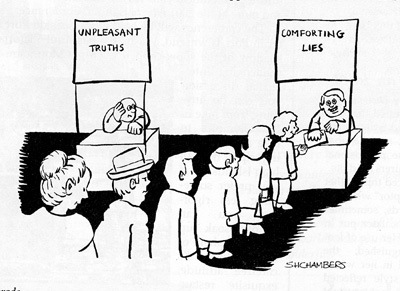

Tempting but wrong

Third, there is little value in identifying missing ingredients or binding constraints (eg “growth diagnostics”). Even if the most important gaps could be reliably identified—and we often get even this step wrong—those gaps are the consequences, not the causes, of the condition of the economic and political system.

adaot and survive

Fourth, we should avoid creating protected incumbents that become obstacles to change, whether in government (through large, unaccountable government-to-government aid flows), the private sector (through subsidised loans or guarantees, or trade preferences), or civil society (external finance can create “astroturf” organisations that are not accountable to their members). All these types of well-meaning intervention offer, at best, short-term gains at the expense of long-term damage to the dynamic evolution of the economy and polity.

Fifth, the problem is not “lack of capacity” – or rather, the lack of capacity is itself a consequence of the system and will not be rectified by technical cooperation or capacity building programmes. This might be why large-scale evaluations of technical assistance programmes generally declare them to be a failure. (See for example this World Bank review).

If we want to accelerate development we have to focus on improving the system’s capacity to adapt. As in nature, adaptive efficiency depends on two things: variation and selection. Interventions which improve or accelerate variation and selection will tend to help the system to generate the self-organising complexity we call development.

Examples of policies that rich countries control that can help to bring this about in developing countries include:

a. Trade. Access to overseas markets increases the returns for successful firms and so increases investment and jobs. It sharpens competition and increases contestability and so drives improvements in performance. It increases access to imported inputs (such as machinery, business services and knowledge) which increase productivity. And it helps accelerate the circulation of ideas and skills. And unilateral trade concessions like the African Growth and Opportunities Act, enacted by the US Congress in 2000, show how rich countries can unilaterally grant developing countries better trading opportunities, without requiring an immensely costly, reciprocal multilateral negotiation process at the WTO.

b. Tax. At the heart of every successful society is a social contract between the state, citizens and business; and tax plays a key role in enforcing that contract. Tax provides the revenues that enables the government to provide essential infrastructure and public goods, and it fosters the accountability to citizens on which good government depends. Rich countries should do more than provide technical assistance: they should change the mechanisms for international tax cooperation and information sharing to enable developing countries to start to build a sustainable domestic tax base, including by making sure multinational corporations pay their fair share of taxes in the countries in which they’re due.

b. Tax. At the heart of every successful society is a social contract between the state, citizens and business; and tax plays a key role in enforcing that contract. Tax provides the revenues that enables the government to provide essential infrastructure and public goods, and it fosters the accountability to citizens on which good government depends. Rich countries should do more than provide technical assistance: they should change the mechanisms for international tax cooperation and information sharing to enable developing countries to start to build a sustainable domestic tax base, including by making sure multinational corporations pay their fair share of taxes in the countries in which they’re due.

c. Migration. Apart from improving the wellbeing of migrants themselves, increases in migration opportunities—even the chance to work temporarily in rich countries– for people from developing countries increases the circulation of ideas (for example, countries whose students go to university in democracies tend to improve governance at home) and increases the returns to skills, so encouraging investment in education, and directly benefits the sending communities through remittances and return migration.

d. Transparency. Greater openness facilitates accountability. Outsiders can be transparent about the aid they give and the payments they make to governments and public enterprises, for example for oil and other mineral concessions. They can through their own behaviour encourage the spread of openness as an international norm, for example open contracting, open data and public registries of the owners of companies, thereby expanding the spread of transparency and domestic accountability across the developing world.

e. Media and “connective action”. Though mobile phones are not a ‘silver bullet’ for development, there are examples of the way that improved communications and media have helped make governments more accountable and markets more effective. For example, there is evidence that when voters know more about the policies of candidates in elections, they are less likely to vote on ethnic lines and politicians are more accountable in office. Use of mobile phones can reduce election fraud (for example, in Ghana in 2004) and crowdsourced reporting of bribery might help to reduce petty corruption.

f. Access to ideas. The ability of developing countries to catch up with rich countries has been hampered by obstacles to the spread of new technologies and knowledge – such as medicines, software, machinery and know-how. Industrialised countries have done little to live up to their treaty commitment to facilitate technology transfer, codified in Article 66.2 of the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) Agreement.

g. Innovation. External donors can promote innovation by increasing the returns to success (for example, through Advance Market Commitments or Development Impact Bonds), and by acting more like venture capitalists and less like retail bankers. The key in such interventions is to avoid picking winners, even though there might appear to be short term benefits to doing so. The goal is to build industries that are successful and which are capable of remaining competitive through a process of innovation and adaptation. This is most likely to include a degree of creative destruction, in which new firms enter the industry, replacing less successful incumbents. Donors should stop giving subsidies to particular companies in ways that make these markets less contestable. For example, a country may be less likely to evolve a thriving, successful microfinance industry of its own if many of the most promising opportunities have been taken by externally-subsidised microcredit firms.

Many development interventions try to imitate the consequences of a successful system instead of thinking about how to enable the system to find successful solutions to its own problems. This difference matters because interventions to “plug the gaps” or “relax constraints”, however well-intentioned, may be harmful for the long-run evolution of the system. We provide aid to governments in ways which can make them less rather than more accountable; we provide humanitarian food aid in ways which can destroy markets for local producers; we subsidise civil society organisations and can make them less accountable to their own communities; we subsidise firms to invest abroad in ways which can make them less vulnerable to competition, and so make industries less contestable and innovative; we limit migration in the name of avoiding a brain drain; and through policy conditionality we try to make particular policies better (at least in our view) but usurp the emergence of contested national politics. All these interventions may undermine the long run evolution of a successful, inclusive economic and political system.

enable the system to find successful solutions to its own problems. This difference matters because interventions to “plug the gaps” or “relax constraints”, however well-intentioned, may be harmful for the long-run evolution of the system. We provide aid to governments in ways which can make them less rather than more accountable; we provide humanitarian food aid in ways which can destroy markets for local producers; we subsidise civil society organisations and can make them less accountable to their own communities; we subsidise firms to invest abroad in ways which can make them less vulnerable to competition, and so make industries less contestable and innovative; we limit migration in the name of avoiding a brain drain; and through policy conditionality we try to make particular policies better (at least in our view) but usurp the emergence of contested national politics. All these interventions may undermine the long run evolution of a successful, inclusive economic and political system.

A policy to promote development would focus much more on helping the system to evolve, and much less on filling the gaps which are left by systems that have not yet done so.

The quest for sustainability in foreign aid projects over the last four decades has done untold damage. Projects that might have benefits in the long run have been structured and financed as if they could reasonably achieve success or become self-financing within a few years, and are declared failures when they do not. Health services that should have been free have been required to charge user fees in the name of sustainability, so denying access to the poor. It is understandable that aid donors and aid recipients alike would rather imagine that development projects will catalyse permanent change than accept that they will be permanently engaged in an international system of welfare payments. But despite the rhetoric, few programmes have actually achieved the sustainability that they were required to promise.

Sustainability has been elusive in practice because the aid industry thinks too much about gaps and too little about systems. Interventions that accelerate the evolution of a successful economic and social system can be catalytic; interventions that ignore the complexity of the system and only try to fill the gaps that it leaves or imitate its consequences will work only for as long as the intervention continues.

Improvements in the adaptive efficiency of the system are the new sustainability.

Tomorrow Jean Boulton responds on the politics of complexity

May 11, 2015

Which bits of advice do developing country decision makers actually listen to? Great new research

Another interesting feedback loop in the aid system: a new report, The Marketplace of Ideas for Policy Change summarizes a

The marketplace

survey of 6,750 policymakers and practitioners in 126 low- and middle-income countries to find out which of the innumerable bits of advice and analysis churned out by aid agencies, international organizations and NGOs actually influence their work.

What’s most alarming is how original this is – I am still looking for a similar exercise on the MDGs, which might have made the whole post-2015 process less of a donor-driven gabfest. Right now the SDG wallahs should be reading this paper and asking – what kind of reporting structure might actually influence government behaviour?

A lot of the conclusions had me scribbling ‘NSS’ (No Shit, Sherlock, since you ask) in the margin: influence is to some extent a function of how much the organization spend on marketing? Wow, who would have thought it! But some are worth noting, and a few are genuinely surprising. Here’s some that jumped out for me:

Advocating on family/gender policy has the best chances of success, anti-corruption the worst: ‘The family and gender policy domain is one characterized by relatively high levels of external assessment influence, relatively low levels of (net) domestic opposition to reform, and reasonably good odds of success in reform implementation. This finding suggests that external efforts to encourage and support family and gender reforms may be particularly fruitful. Anti-corruption stands apart as the policy domain with highest level of (net) domestic opposition to reform and the worst track record of reform implementation.’

Similarly, ‘The democracy and decentralization policy domains appear to be least susceptible to external influence at the agenda-setting stage.’ Yup, that’ll be power and politics, then (see NSS).

Similarly, ‘The democracy and decentralization policy domains appear to be least susceptible to external influence at the agenda-setting stage.’ Yup, that’ll be power and politics, then (see NSS).

‘External assessment influence is strongest at the agenda-setting stage of the policymaking process.’ – i.e. get in early in the policy funnel, help define problems etc. Compatible with the whole PDIA approach.

‘Paying attention to “nuts and bolts of government” may result in greater assessment influence.’ Please note, all campaigners – think about advocating on boring but important stuff like data collection, staff training, info management.

‘Country-specific diagnostics generally exert greater influence than cross-country benchmarking exercises.’ OK that’s interesting – maybe publishing regional league tables, naming and shaming etc is not the best way to influence government (but perhaps tables comparing regions or cities is?)

‘External assessments that rely on host government data are more influential.’ Use government data, rather than your own, or some international body’s, and you are half way to getting buy in.

‘The longer an assessment’s track record of publication, the more influential it becomes vis-à-vis others.’ International organizations tend to have much more staying power than INGOs, producing annual reports on this or that, which slowly accumulate brand awareness and impact. By hopping from issue to issue, INGOs may keep the media interested, but they sacrifice impact.

‘Neither incentives nor penalties seem to easily explain assessment influence.’ Oh good, we don’t have to pay people to read our reports.

‘Prescriptive assessments appear to be slightly more influential than descriptive assessments, and decision-makers in the developing world seem to want more, not less, specific policy guidance.’ OK, that’s definitely a challenge to all the complexity wallahs and Doing Development Differently crowd who say that outsiders should focus on highlighting problems, not suggesting solutions (which need to be designed by local actors).

‘Assessments were influential because they promoted reforms that aligned with the priorities of national leadership.’ A ‘working with the grain’ argument that it’s best to try and influence ongoing processes rather than start new ones.

‘Senior government leaders and their deputies engage with external assessments in different ways. One potential interpretation of this finding is that leaders, mindful of their domestic audiences, project strength in the face of external pressure, while their deputies work behind the scenes to secure material rewards from donor agencies and international organizations.’ Love it!

Some important findings on the limits of external influence:

‘The picture that emerges is not one of governments being cajoled or coerced into pursuing reforms that align with donor priorities, but rather that governments pick and choose assessments based on whether they advance domestic priorities.’

‘External sources of analysis and advice rarely help to neutralize opposition to reform or build coalitions in support of policy change.’

And on the range of country types:

‘Some of the most successful reformers “go-it-alone” and shield the domestic policy formulation and execution from external pressure (e.g., Rwanda and Ethiopia), while others rely more heavily on external sources of analysis and advice (e.g., Liberia and Georgia).’

Some weaknesses:

It’s just a survey – so no in depth interviews, focus groups etc to dig deeper, which I am sure would have produced further insight.

Massive blind spot on critical junctures – policy makers everywhere ignore advice until they need it, which is often after a scandal, crisis or obvious failure in previous policy. Building detailed timelines with decision makers would have revealed much more about how they take up policy advice and analysis at such moments.

Also nothing on the role of people and institutions outside government in persuading the state to adopt particular pieces of analysis – coalitions, insider-outsider alliances etc. This is a world where civil servants and pols read or don’t read/listen to reports – in real life, things are a bit more complicated than that.

The good news is that the AidData lab that conducted the survey plans to repeat it (and so accumulate influence, presumably). Now can someone apply this approach to the SDGs, please?

May 10, 2015

Links I Liked

Sometimes failure is not ‘failing faster, failing forward etc’. It’s just… failure. Dilbert explains

There seems to have been a polite punch-up over the SDGs at the recent Gates Foundation shindig, according to Tom Paulson. SMART targets (read apolitical, health-dominated and few) v holistic (read laundry list).

How one NGO helps communities negotiate with investors for proper valuation of natural resources

Clowns who care – helping kids in Syrian refugee camps to laugh is important aid work

‘International analysts predict the seeds of a so-called “American Spring,” fomented by technology’. If Baltimore happened in a foreign country, this is how the Western press would cover it [h/t Ian Birrell, even tho he never h/ts back.....]

Nepal aftermath:

Nepali migrants sent $6bn back home in 2013, approx 1/3 of the country’s GDP. They’ll send a lot more this year

Lessons from Haitian earthquake response, by Christian Aid’s Haiti rep Prospery Raymond (no domestic politics, though)

Reading Harry Potter increases young Europeans’ tolerance of immigrants and gays. Experimental research findings.

Schoolboy pretends to be son of Tajikistan’s president, extracts $50k bribe from a gullible citizen by promising to get him some land, then gets caught. His mistake? Actually phoning up government officials to extract the land.

‘My buttocks are smooth, my mind is clear: vote UKIP’. Vox pop high/lowlights from Channel 4’s coverage of UK elections, proving that Brits are deeply odd. If you want a more sober assessment of British politics over next five years, this piece is a good place to start.

May 8, 2015

Book Review of ‘Advocacy in Conflict’ – a big attack on politics and impact of global campaigns

[Oops. This was supposed to go up next Thursday when the book is published, but I hit the wrong button and posted it by mistake - blame the UK elections for keeping me up all night.....]

If you work in advocacy, especially the international sort, this is a necessary but painful read – it’s hard finding yourself the  brunt of a 300 page sustained critique, but you need to hear it. Based on a series of chapter case studies, covering Burma, Guatemala, Gaza, the DRC, South Sudan and of course the infamous Kony 2012 campaign, as well as thematic chapters on disability rights, the arms trade and land rights, Advocacy in Conflict brilliantly explores the contradictory pressures on transnational advocacy: northern campaigners’ need to simplify, grab headlines and declare victory v the messy reality of achieving long term structural change in the complex social and political environments of countries wracked by conflict.

brunt of a 300 page sustained critique, but you need to hear it. Based on a series of chapter case studies, covering Burma, Guatemala, Gaza, the DRC, South Sudan and of course the infamous Kony 2012 campaign, as well as thematic chapters on disability rights, the arms trade and land rights, Advocacy in Conflict brilliantly explores the contradictory pressures on transnational advocacy: northern campaigners’ need to simplify, grab headlines and declare victory v the messy reality of achieving long term structural change in the complex social and political environments of countries wracked by conflict.

The authors explore ‘the extent to which recent trends in transnational advocacy have deviated from core principles of responsible activism’, and focuses on the work of ‘professionalized Western advocacy concerned with particular conflicts.’

‘Our central argument is that the development of these specific forms of activism, in which advocates have shaped strategies to fit the requirements of marketing their cause to Western publics, and adapted them to score tactical successes with Western governments (especially that of the USA) has led to the weakening or even abandonment of key principles, including receptivity to the perspectives of affected people and their diverse narratives and attention to deeper, underlying causes and therefore a focus on strategic change rather than superficial victories’.

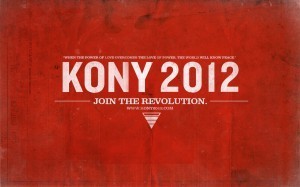

And it’s hard to get more superficial than Invisible Children and Kony2012 – a campaign that purported to urge the US government to do something it was in fact already doing, went viral, crashed and was then followed by its originators, Invisible Children, which announced this year that it is closing down. The campaign rang all sorts of alarm bells, for example

erm, what revolution?

by calling for military intervention by the US. The book draws comparisons with the ‘hashtag activism’ of the #BringBackOurGirls campaign, that achieved precisely zip in Nigeria, but made a lot of activists feel good about themselves everywhere else.

The tone is pretty jaundiced. Alex de Waal, who edited the book, frames activism as driven by ‘three abiding impulses: the personal salvation of fulfilment of the activist her- or himself; protection of the social order through charitable assistance to those in need, who might otherwise be subversive of that order; and an ethic of solidarity in support of radical social change.’ Oh well, at least we get one out of three that is not a total putdown.

The country chapters are fascinating: the book argues that both Aung San Suu Kyi and Nelson Mandela were elevated to prominence over their respective movements by the needs of Western campaigners. The difference was that Mandela was clear about using the profile for the collective purposes of the ANC, whereas ASSK lost touch with Myanmar’s grassroots movements.

In her chapter on conflict minerals in the Congo, Laura Seay argues that the ‘Enough Project’ campaign pressuring international companies that purchase minerals from eastern DRC to certify that their minerals are ‘conflict free’ has damaged both the country’s economy and politics. There are echoes here of the infamous unintended consequences of trying to ban child labour in Bangladeshi garment exports – thousands of kids being expelled from the factories into far worse ways of earning a living, while the campaigners celebrated their success.

On South Sudan, Alex de Waal argues that DC lobbyists needed to keep it simple for US politicians, so anointed the Sudan  People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) as the Robin Hood figure, explaining away or justifying human rights abuses, corruption and other unsavoury details.

People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) as the Robin Hood figure, explaining away or justifying human rights abuses, corruption and other unsavoury details.

There’s plenty more, but I’ll skip to the conclusions. The book argues for a ‘reclaimed activism’ which is the antithesis of Kony2012: ‘activism that prioritizes the empowerment of people as the basis for transformational change over media impact, and that is accountable to the people most affected by an issue.’

It identifies four common themes that should guide would be reclaimers:

‘1. Empower local actors to define and lead any efforts on their behalf, including identifying the advocacy targets, methods, narratives and definitions of success

2. Avoid activism that addresses only specific occurrences or news events without addressing the underlying structural problems

3. Accept a wide swathe of actors and encourage them to participate in campaigns and movements

4. Accept and promote diverse voices and understandings of an issue. Activism should reject singular narratives.’

From a wonk perspective, this all seems sensible, even obvious. But put yourselves in the shoes of one of the reviled ‘transnational activists’ and it makes you want to slit your wrists. ‘Reject singular narratives’ – look forward to reading that press release….. I guess the upshot is that they are calling for smaller, better campaigns rather than big hits which end up going nowhere.

But there’s also a big missing piece, at least in relation to Oxfam – what if you are involved in both advocacy and on the ground emergency responses? If you’re running refugee camps for the victims of conflict, there’s a whole new swathe of complications. What if criticising the government (however justified) gets you chucked out of the country and the camps closed down? In Oxfam at least, being operational is a double-edged sword for advocates – it confers legitimacy and genuine first-hand knowledge on which to base advocacy messages, but significantly constrains what we can/can’t say.

What do you think?

May 7, 2015

Why is support for gender equality mainly growing in urban areas?

Guest post from the LSE’s Alice Evans from the LSE

Across the world, support for gender equality is rising. More girls are going to school. Women are increasingly being recognised and supported in historically male-dominated domains, such as employment and politics. Growing numbers of men are sharing unpaid care work. In short, young women are ‘beginning to envision a future similar to young men: education, independence, greater financial autonomy, and shared responsibility for their family’ – comments Boudet et al (2013: 37), drawing on a comparative study of twenty countries commissioned by the World Bank.

However, such egalitarian social change is largely restricted to urban areas. ‘In rural areas, [men] appear less willing to accept women’s changing roles and aspirations… [O]ne participant to a women’s focus group in in semi-rural South Africa, maintained that ‘We do not have any job opportunities, our husbands assault us, and most of the time the tribal court favors the man. So really nothing has changed”’ (Boudet et al, 2013: 140). These observations are consistent with quantitative data from Afrobarometer, World Values Surveys and Demographic and Health Surveys.

Why is growing support for gender equality largely limited to urban areas?

To investigate this topic, I set off for Zambia, where I interviewed rural-urban migrants as well as long-term rural and urban residents. My ethnographic research was based in two locations: Kitwe (the largest city on the Zambian Copperbelt and Chinsanka (a remote village on the banks of the Luapula river). Both areas speak Bemba, in which I am fluent.

To investigate this topic, I set off for Zambia, where I interviewed rural-urban migrants as well as long-term rural and urban residents. My ethnographic research was based in two locations: Kitwe (the largest city on the Zambian Copperbelt and Chinsanka (a remote village on the banks of the Luapula river). Both areas speak Bemba, in which I am fluent.

My life histories, group discussions and observations point to the ‘disruptive’ tendencies of the urban.

First, urban heterogeneity increases the likelihood of exposure to flexibility in gender divisions of labour. Urban girls see women working: as market traders, miners, mechanics, managers and even Government Ministers. Seeing a critical mass of women performing socially valued roles seems to – slowly and incrementally – erode gender stereotypes, relating to competence and status. It broadens their aspirations and hardens their resolve to progress in education.

Urban heterogeneity also increases the likelihood of exposure to men sharing care work. This is (very) slowly and incrementally undermining presumptions about cultural expectations, enabling a positive feedback loop. As Chilando (a 41 year old tomato trader, rural-urban migrant) comments:

‘They are very different, the village and town. It is women who do all the work at the village. Right here in town men cook and help with washing up, but that can’t possibly happen in the village! He [my husband] helps me here. They see women going to the market… we become tired; they come so we can help each other… [But] the rules in the village are very tough, they’ll be laughing at you. Here he’s found his friends helping their wives. Things are very different in the village’ [translated].

In remote rural Chinsanka, men are revered as providers. It is they who venture out, for several weeks at a time, into the crocodile-invested Luapula river. Traversing great distances in small wooden paddle boats. Hauling in the nets at night. This is ‘men’s work’. And families are dependent upon it. Women ‘just sit’. In this context, ‘there’s little else girls see and admire besides getting married and having children’, commented Rebecca (a married 40 year old fish trader). Furthermore, with limited exposure to flexibility in gender divisions of labour, her parents will likely stereotype men as breadwinners and thus educate their sons instead. This perpetuates gender status beliefs – that men are more suited and entitled to positions of leadership – as reflected in the Afrobarometer data below:

A second difference between urban and rural areas is money. Reflecting a global phenomenon, Zambian women’s unpaid work is often unrecognised and unappreciated. Cooking, cleaning, sweeping, fetching water, weeding, planting, harvesting (for subsistence agriculture) are commonly referred to as ‘just sitting’ (translated). However, earning an income (more common in urban areas) provides a tangible sign of women’s contributions. This disrupts perceptions of men as breadwinners.

Third, greater proximity to government services (such as clinics and police) allows urban women to disrupt biology: control their fertility and secure external support against gender-based violence. Government services not only enable access, they are also perceived as legitimising women’s control of their bodies. This shifts presumptions about cultural expectations. Chinsanka, meanwhile, has no clinic, no police station. Teenage pregnancy rates and fertility are high, increasing dependency on male breadwinners.

What does this tell us about the causes of egalitarian social change? It indicates the importance of exposure to a critical mass of women demonstrating their equal competence in socially valued domains, earning incomes and controlling their bodies. Moreover, it underscores the significance of cultural expectations. Paid work is not enough to empower an individual woman. Even if a rural woman earns an income, her husband is three times more likely to control that money – as compared with urban counterparts in Zambia. Place matters.

What does this tell us about the causes of egalitarian social change? It indicates the importance of exposure to a critical mass of women demonstrating their equal competence in socially valued domains, earning incomes and controlling their bodies. Moreover, it underscores the significance of cultural expectations. Paid work is not enough to empower an individual woman. Even if a rural woman earns an income, her husband is three times more likely to control that money – as compared with urban counterparts in Zambia. Place matters.

Anyway, that’s my emerging theory so far. Very keen to hear alternative perspectives on the causes of rural-urban differences. Further, what might amplify support for gender equality in remote rural areas?

May 6, 2015

How do we get down to the nitty gritty on ‘Doing Development Differently’?

The ‘Doing Development Differently’ network has been going great guns since it launched late last year, with hundreds of  wonks and practitioners signing up to the DDD manifesto. It’s just had its second big get together, a thrilla in Manila – I couldn’t go so Andrew Wells-Dang (Oxfam-Vietnam) reports back.

wonks and practitioners signing up to the DDD manifesto. It’s just had its second big get together, a thrilla in Manila – I couldn’t go so Andrew Wells-Dang (Oxfam-Vietnam) reports back.

Mabuhay! I and about 50 other development wonks gathered for the second meeting of this network following an initial gathering at Harvard University in October 2014, which produced a ‘DDD manifesto’. Whilst some of the prominent voices from the first workshop – ODI’s David Booth, the Asia Foundation’s Jaime Faustino – were also present, the focus of this workshop was on practitioners rather than researchers. (All the presentations and other materials can be found here – in addition to being an undercover blogger for Duncan, I also presented with a DFID colleague on how we are trying out innovations in governance programming in Vietnam)

The idea of ‘doing development differently’, as Duncan’s previous posts have pointed out, is broad (or vague) enough to cover many possible viewpoints. In a way, this can be seen as a strength, as it helps many people adopt the idea. We all want to be different, but different from what? Some participants conceive of DDD mainly as ‘innovation’ or ‘entrepreneurship’, terms borrowed from the equally fuzzy language of business management. More specific, but slightly unwieldy, are the related movements for ‘thinking and working politically’ (TWP), ‘locally-led, politically smart’, and ‘problem-driven, iterative adaptation’ (PDIA) – which is probably the most specific, positive description.

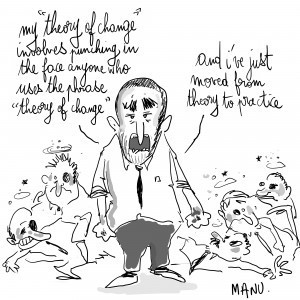

Beware ToC-rage

The engaging panels, open space discussions, and long breaks (love those meriendas!) in Manila focussed on two types of programmes that are problem-driven, iterative, and adaptive, or at least trying to be:

Coalition-building programmes for policy reforms (such as Pyoe Pin in Myanmar, Coalitions for Change in the Philippines, and the Vietnam Coalition Support Programme that I’m involved in). These programmes (as well as SAVI in Nigeria that was also represented) share certain features in common, though interestingly enough, we all mean something slightly different by ‘coalitions’, and our contexts differ in unexpected ways: in Vietnam ‘policy advocacy’ is a neutral term compared to ‘reform’ or ‘change’, but in the Philippines it’s the other way around!

On the second day, we also heard from public sector service delivery programmes – considering examples from Indonesia’s planning ministry, an Asia Foundation initiative in Ulaan Bator, Mongolia, and budget strengthening in ‘fragile states’ in Africa through ODI. These relate to discussions of institution-building working from within the state, a different approach to demand-side governance.

By about the third presentation, it was clear to everyone that many of the same lessons, challenges and experiences arise from multiple cases in varying contexts. If I could summarise a single outcome, it’s that PDIA, or DDD principles, or whatever we call them apply in both of these types of programmes – and probably in many (if not all) others, since the basic context of complex operating environments, multiple partners/stakeholders, and uncertainty of outcomes applies widely.

But once we recognise this, then what? Beyond the general DDD principles – local leadership, stepwise planning, ‘small bets’ and others – perhaps there is a need for more specific guidelines for groups of programmes under the DDD umbrella? For coalition-building programmes, for instance, these might include the value of a challenge function from ‘insider-outsiders’: people who understand our context but also keep one leg outside it. Another key learning is the need to integrate aspects of formal and informal coalitions in our work, since some formality may be necessary to achieve legitimacy and cohesion, but most of the changes that matter happen through personal linkages among individual actors.

For service delivery projects, key issues include how to support reform actors within government agencies, an appropriate

There’s theory, and then there’s practice

role for embedded technical advisers within ministries, and what are supportive, but not interfering, positions for donors as conveners. Another set of guidelines might well apply for ‘working politically’ at a national reform/transition level, and so on. DDD, we all agreed, should not be restricted only to a certain type of governance programme implemented by actors (such as Oxfam and the Asia Foundation) that already follow many of the principles.

With this observation in mind, the workshop organisers posed a series of questions:

How to close the perceived gap between the general agreement on DDD principles and specific applications in practice, so that the principles become a norm, not an exception?

How can the principles be mainstreamed into other sectors, including in traditional large donor programmes such as health and infrastructure?

Can adaptive monitoring tools such as theories of change, strategy testing and contribution analysis be reconciled with donors’ ‘results’ and ‘value for money’ agendas that stress upwards accountability?

Participants (including a number of open-minded donor representatives) sought to identify moderate solutions that might build support within their agencies: setting up innovation funds within larger-scale programs, for instance, or ‘twinning’ DDD-type approaches with bi/multilateral loan projects, budget support, and other ‘business as usual’ strategies to get the money out without a high monitoring burden or fiduciary risk.

These solutions may have merit in some cases, but they take the existing political constraints on donors as a given, rather than identifying ways to advocate for changing it (that is, applying a political economy approach to the donors, not just to programme counterparts).How to apply DDD principles to £100 million programmes is probably the wrong question, since the spending pressures of such a programme almost inevitably exclude the kind of in-depth communication and close relationships among donors, implementing agencies, and local partners that iterative, adaptive development requires. Can donors instead be convinced to fund small-to-moderate sized programmes that spend a much greater percentage of their budgets on analysis, participatory design, and learning, both at the start and during the process?

Other questions emerged from the workshop discussions. How can we (donors, implementers and partners) demonstrate incremental progress over a longer term? It’s fine to talk about ‘small bets’, but DDD can’t be just about quick wins or ‘low-hanging fruit’. Are we willing to persist to achieve outcomes that might take years, like the Filipino excise tax reform campaign, which began in the mid-1990s and succeeded in 2012? Are donors willing to continue funding? Or by contrast, when do we accept that a certain initiative is not working? If we do recognise a failure, are we able to take action, since we have existing relationships and ties with partners, and a built-in belief that with just a little more time and resources, this might work?

I hope that future DDD reflections (already being planned) will take up these and other practical questions, rather than too much navel-gazing about how to spread the DDD manifesto and principles, or whether a particular programme conforms to the principles or not. It would also be good to continue to broaden the participants beyond the middle-aged men (like myself), many of us from donor countries, though often with long experience in one or more developing country contexts. I found that the national and regional staff and managers, both women and men, who were present in Manila had particularly valuable and, dare I say, ‘different’; contributions to the debate.

A handy metaphor

For me, the main value of a few days in Manila is that I came back with several new ideas about the design and implementation choices of the Coalition Support Programme in Vietnam. What does ‘transformational change’ mean for us, and how do we recognise it? How can we combine qualitative assessment and monitoring that is partner-led with ‘harder-edged’ decision making about who to work with, on what issues and for how long? And a final powerful image provided by one of the presenters: of governments (and other bureaucracies) as turtles, with a hard shell evolved over time. If external reformers such as multi-stakeholder advocacy coalitions bang on the shell, the turtle just withdraws further inside and waits for the banging to end. How can we instead get under the shell, encourage the turtle to poke its head and feet out and take steps forward?

May 5, 2015

Active citizens holding Britain’s politicians to account – why can’t the rest of the UK election campaign be more like this?

The UK general election takes place  tomorrow. I’ve spared you so far, but on Monday I went to what has to be the most enjoyable and substantive event of the election campaign – watching party leaders and ministers being grilled by an ‘accountability assembly’ of the community organisation Citizens UK in a packed Methodist Central Hall, within spitting distance of the Houses of Parliament.

tomorrow. I’ve spared you so far, but on Monday I went to what has to be the most enjoyable and substantive event of the election campaign – watching party leaders and ministers being grilled by an ‘accountability assembly’ of the community organisation Citizens UK in a packed Methodist Central Hall, within spitting distance of the Houses of Parliament.

Citizens UK was founded in East London some 25 years ago, based on the principles of US community organising guru Saul Alinsky. Declaration of interest – my son Calum has worked for Citizens UK for around 4 years now, having joined them straight out of university.

Its approach is fascinating. I’ve been to a few of these now, and the format is pretty fixed and very effective. A lot of fun – church and school choirs are a speciality – interspersed with powerful testimony from those affected by the issues Citizens UK is campaigning on (living wage, indefinite detention of asylum seekers, awful care standards for the elderly and vulnerable and exploitation by payday lenders). It was very moving (memo to self, bring a hankie next time): asylum seekers who had attempted suicide in detention, cleaners who lost their jobs for demanding a living wage (and been reinstated after a public campaign), carers with horror stories. All presented by a mix of feisty and sharply-dressed youth leaders (suits and high heels), and older authority figures (lots of dog collars, skull caps and robes, along with the weirdly militaristic outfits of the Salvation Army).

Then the politicians are allowed onto the stage, one by one, given precisely 4 minutes each to pitch for their party, and then are cross examined on the detailed campaign asks on changes in policy, targets, time limits or simply a promise to engage with Citizens UK after the election. Vague or evasive answers are challenged, and promises extracted – I’m pretty sure the politicians end up making extra commitments under the pressure of the format and the crowd.

Then the politicians are allowed onto the stage, one by one, given precisely 4 minutes each to pitch for their party, and then are cross examined on the detailed campaign asks on changes in policy, targets, time limits or simply a promise to engage with Citizens UK after the election. Vague or evasive answers are challenged, and promises extracted – I’m pretty sure the politicians end up making extra commitments under the pressure of the format and the crowd.

As a model of active citizenship, it is hard to beat. Standout points include:

The base of Citizens is largely religious institutions and schools, more than trade unions, political parties or other traditional players. That gives it a vibrance and a non-partisan quality, but also means it is founded on institutions that mean a lot to the lives of normal people. It feels relevant. These institutions are where values are formed, and social capital is built. I found myself wondering whether they’ve missed any other long term, collective institutions – sports fans maybe?

That coming together of faith, education and politics felt like a completely natural fit – building together a moral narrative for a just future. What seemed odd was why it is so absent in the rest of politics.

The optics of the hall were striking – 2200 activists including cleaners working in government on rock bottom wages, refugees and asylum seekers, care workers: the kinds of people who appear fleetingly (and usually tokenistically) in the rest of the election campaign, only this time their issues and views dominated. Brilliant – it felt like the Britain I know.

Relentless positivity, from the opening song (a bunch of achingly cute school kids singing Pharrell Williams’ ‘Happy’). We were told ‘we do not boo or heckle, but we do cheer and applaud when we hear our views reflected’ and everyone stuck to that. Well almost everyone. A lone heckler of David Cameron’s stand-in, Sajid Javid, was promptly hushed by the crowd, but sure enough, the Guardian headline read ‘Tory minister heckled over detention of asylum seekers’. Sigh. The Guardian diary piece on the event was much better (and funnier).

Even more striking was that all the politicians were first congratulated on promises kept and progress made.  Impressively, several commitments extracted from a similar event in 2010 had been met – ending child detention of asylum seekers, taking action to cap the interest rates of payday lenders. Nick Clegg in particular (beleaguered Lib Dem leader, in coalition with the Tory government since 2010 and facing annihilation on Thursday) looked rather startled to have praise showered upon him for a change. Everyone got flowers.

Impressively, several commitments extracted from a similar event in 2010 had been met – ending child detention of asylum seekers, taking action to cap the interest rates of payday lenders. Nick Clegg in particular (beleaguered Lib Dem leader, in coalition with the Tory government since 2010 and facing annihilation on Thursday) looked rather startled to have praise showered upon him for a change. Everyone got flowers.

A huge effort to remain non-partisan – a choir singing God Save the Queen, liberal use of quotes from Winston Churchill (“it is a serious national evil that any class of His Majesty’s subjects should receive less than a living wage in return for their utmost exertions” – not bad eh?). It was probably the most civilised event of the election, as well as one of the most substantive.

Carefully crafted ‘asks’ to the politicians which are designed to be significant but within the bounds of political possibility, arrived at by shuttling between the Citizens UK grassroots and the decision makers. Example: a time limit rather than indefinite immigration detention. For its full 12 page election manifesto go here.

Overall, the tone could not be more different from the hectoring, finger-wagging tone of most election events (and I fear, many activist campaigns), and felt far more effective in engaging the decision makers and winning some small victories, while at the same time empowering and organising people and communities who too often remain on the margins of political life. The fact that it got two out of three party leaders to show up 3 days before the election is testament to its pulling power (and the expressions of polite disappointment at David Cameron breaking his 2010 promise to show up here were exquisitely done).

For a feel of the event, here’s video highlights starting with the Sajid Javid (Conservatives), Nick Clegg (Lib Dems) at 22 minutes, and Ed Miliband (Labour) at 48m. Check it out. I think it’s fair to say that Javid started well, but then messed it up, whereas Clegg and Miliband smashed it.

May 4, 2015

Links I Liked

Grammar pedants rally behind the Oxford comma, [h/t Alexander Macleod]

‘International analysts predict the seeds of a so-called “American Spring,” fomented by technology’. How press would cover Baltimore if it was in a foreign country. [h/t Ian Birrell]

Smart Owen Barder essay on the future of aid

Planetary Boundaries and Human Prosperity. Kate Raworth teams up with Johan Rockstrom

This is how fast the US changes its mind (aka they say no until they say yes). [h/t Chris Blattman]

This is how fast the US changes its mind (aka they say no until they say yes). [h/t Chris Blattman]

God and global warming: the Vatican urges action on climate change

Je suis migrant. (If only). [h/t Kenneth Roth]

Why migration matters: Nepali migrants sent $6bn back home in 2013, roughly 1/3 of country’s GDP (and they will send home a lot more in response to the earthquake).

New TripAdvisor style platform allows 1m Syrian refugees in Lebanon to search and rate aid and commercial services

Who’s gonna get it on, come this Thursday’s UK General Election? Another coalition looks highly likely – cue this brilliant lip synching from Sky News [h/t Charlie Beckett]

April 30, 2015

What makes it possible to do joined-up programmes and advocacy? And what prevents it?

Here’s a second instalment on ‘influencing’, following yesterday’s piece from Erinch Sahan

Down with siloes

There’s a lot of talk in the aid biz about ‘getting out of our siloes’ – the traditional division of labour between ‘long term development’, ‘humanitarian’ and ‘advocacy’. I’ve seen this most starkly in some classic campaigns like Make Poverty History or Make Trade Fair, which seemed to have very little connection to Oxfam’s work on the ground.

We want to change that by adopting a ‘one programme approach’ that abolishes the distinction between running projects and trying to change the broader system. One surprisingly effective way to overcome such divisions is to introduce a new word that doesn’t belong to any one camp – in our case it is ‘influencing’, which is now all over Oxfam’s organigrams and strategy documents like a rash. So I’ve been looking for examples where such joined-up influencing is actually happening, and come up with a bit of a typology of the situations in which it seems most likely to appear – feel free to pull it to pieces.

The Credibility of Boots on the Ground: It’s a lot easier to get the attention of senior officials or ministers if you have ‘skin in the game’ in the shape of programmes on the ground. In the Water and Sanitation programme in Tajikistan, our existing work on WASH gave us the credibility to ‘convene and broker’ a range of government departments, donors, private sector organizations and CSOs and come up with some really important institutional and legal innovations.

It can work the other way too – campaigns can open doors for programmes: In Vietnam I once, literally, got red carpet treatment from the government because they liked our report on the accession terms being demanded for its entry to the WTO. Our advocacy on global burden-sharing around the Syrian refugee crisis has led to high level access to the Jordanian royal family and opened up some space for our programmes.

It can work the other way too – campaigns can open doors for programmes: In Vietnam I once, literally, got red carpet treatment from the government because they liked our report on the accession terms being demanded for its entry to the WTO. Our advocacy on global burden-sharing around the Syrian refugee crisis has led to high level access to the Jordanian royal family and opened up some space for our programmes.

Pilots and demonstration effects: Proving that what you are advocating for actually works on the ground can be a powerful way of convincing policy makers to take a look. In Vietnam, we involved the local government in a programme to introduce child-centred methodologies in areas where ethnic minority girls were dropping out of school. The results were so spectacular (and Vietnamese officials so open to evidence-based policy making) that we ended up helping to revise the national teacher training materials.

The link between programme and advocacy seems to be particularly obvious in humanitarian work. In Liberia 5 INGOs with major Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) programmes helped set up an advocacy coalition with local NGOs to influence the country’s transition from emergency relief to long term development work. They used a combination of research, public campaigning and multi-stakeholder dialogues to drive WASH up the public agenda ahead of the 2011 presidential election – political parties revised their manifestos to sign up to the campaign, and President Sirleaf publicly committed her government to making WASH a top priority.

Capacity Building: In the DRC, we have worked with partners to set up and support ‘citizen protection committees’ to engage in advocacy with the local state and other armed actors.

As Erinch Sahan discussed yesterday, we’re also promoting a one programme approach in our livelihoods work. Supporting and strengthening producer organizations is often the first step to them advocating for better deals from government or the companies that buy their stuff (or supply them with inputs). In Sri Lanka, our local partners worked with 1,300 women in the coir (coconut fibre) industry to develop entrepreneurship skills, and then worked with them to influence private sector buyers, banks and the government to revitalize the coir industry and support small-scale women producers. The women’s incomes tripled.

Critical Junctures: Sometimes, you don’t know how all that long-term capacity building work is going to pay off until something happens. In Pakistan, when the government passed a new law on the Right to Education in 2010, years of investment in education, women’s leadership groups and other bodies created the footsoldiers for an impressive campaign on its implementation.

New threats: policy makers are particularly open to (even desperate for) answers when something new comes along. Take Ebola. The programming we have done around community engagement and active contact tracing influenced (albeit belatedly) the government of Liberia’s and international agencies’ approach to tackling the epidemic – an exclusive focus on medical treatment won’t work and it is critical to build trust with communities to change risky behaviour patterns and pro-actively find people who may have or be at risk of contracting the virus.

Or Climate Change. Words like ‘resilience’ span the siloes just as ‘influencing’ does. In Armenia some programming around  climate change adaptation for women involved in fruit production (adapting to out of season frosts, hailstorms and more erratic rainfall) opened up the political space for Oxfam and its partners to advocate for rethinking national rural policy. The resulting economic and resilience policy could almost have been written by Oxfam.

climate change adaptation for women involved in fruit production (adapting to out of season frosts, hailstorms and more erratic rainfall) opened up the political space for Oxfam and its partners to advocate for rethinking national rural policy. The resulting economic and resilience policy could almost have been written by Oxfam.

There are plenty of other examples under all the usual NGO themes (livelihoods, humanitarian, essential services), but this gives you the general idea. But they are the good examples, the positive deviants – what’s stopping the rest of us from following suit? Conversations with a range of Oxfam colleagues point to some of the obstacles:

Organizational structures: people are still organized into and identify with their tribe within Oxfam – by function (humanitarian response, long term development, research, advocacy, MEL etc) or theme (health, education, WASH). Often the divisions are greater in HQ than in the field (where people have to multi-task more). The sub-tribes tend to have different aims, values and cultures (to caricature, advocates want to see changes in law, policy or spending decisions, while programme people want to see changes in people’s lives; humanitarian and livelihoods people like to do it themselves and see tangible, attributable results, whereas governance, essential services and campaigns are protesters wanting to shake up the whole system).

Financing: as long as funding for the 3 siloes is separate, it will be harder to join up

MEL: we need monitoring, evaluation and learning to include influencing as part of its design – what’s the best combination of process, brevity, accessibility and rigour for persuading decision makers?

Don’t we do this already? The examples here show that we sometimes are, but I would argue that many of them are in spite of Oxfam/the aid business, not because (often down to inspired project leaders, for example). How do we shift to actively encouraging this approach?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers