Duncan Green's Blog, page 164

May 27, 2015

What kinds of women become leaders, and how can we support them?

Some of Oxfam’s most interesting work concerns women’s leadership – how to promote it, what impact it has etc. But what

Pakistan

seems a convincing case study to me can be dismissed as an anecdote by a sceptic. For people wanting something more systematic, check out the ODI’s recent ‘Support to women and girls’ leadership: A rapid review of the evidence’, by Tam O’Neil and Georgia Plank, with Pilar Domingo.

It’s a proper, nuanced 28 page literature review, full of caveats, definitions, assumptions and discussion of the gaps in the evidence. But I fear it misses one rather large trick: by focussing mostly on women’s leadership in formal (and more often national) decision-making processes, the paper, the research it summarizes, and the programmes they in turn study the paper ignore the importance of women’s informal activism (in church groups, CSOs, activists working on specific issues of social justice like minority rights or fighting the appropriation of community land) – they are still “leadership”, but less formally recognized and defined.

That matters because such informal leadership emerges as critical both in the IDS Pathways research and much of Oxfam’s programme and research, so the ODI survey cannot be applied to all work on leadership, just to that smaller world of formal ‘decision making’.

Keeping these caveats in mind, what does the paper say? I’ve gone through and cut and selected some of the most interesting bits (with apologies to the authors for butchering their text):

‘Based on case studies, including life histories, of women in different levels of government in eight countries, Tadros (2014) found the profile of women leaders to include the following common factors: women being married, professional backgrounds, ‘nurturing’ or community-facing occupations (e.g. teaching, social work) and education, with a correlation between level of education and level of government office.

The Champions Project at Harvard University seeks to understand why some girls from disadvantaged families in India are able to reach university. Their survey data (n=800) strongly suggests family attitudes and behaviour (‘mentorship’) – in particular whether close family members such as parents and older brothers provide psychological and financial support – are more important than targeted gender education programmes.

Uganda

The importance of role models: A study of the effect of female political leadership on adolescent girls in India found presence of women on village councils, enabled by affirmative action, had a positive influence on girls’ career aspirations and educational attainment (Beaman et al., 2012).

Family background and home environment: The potential of individual women to develop and exercise leadership capabilities may be attributable, in part, to their family background, in particular having a stable, relatively prosperous childhood where girls are encouraged to pursue a good education and come under less pressure to contribute to the family income (Madsen, 2010; Singh, 2014). However, family background and home environment are also critical to the leadership potential of women in adulthood. Women struggle to enter politics without the cooperation of their families, in the form of either psychological support and encouragement, especially from husbands (Singh, 2014), or help with child care and other domestic responsibilities, particularly from daughters and other female family members (Madsen, 2010, Singh, 2014).

Tadros (2014) also found home environment and other ‘private’ spaces to be significant as incubators for women’s political leadership. Where other family members, such as fathers or husbands, are involved in politics, the home becomes a place for ‘political immersion’… Family connections can influence women’s pathways to political power in more direct ways, as when women follow their fathers or husbands into political office. Much less empowering is when quotas are gamed to “use” female relatives as a proxy or ‘front’ for the usual political interests.

There is broad consensus however, on the importance of quotas or measures to support women’s presence in formal political space, including in terms of the symbolic value and socialisation effect this has on shifting perceptions about women in public space. While the evidence shows quotas by no means assure substantive representation of gender equality agendas, they do appear to have impacts on social norms and perceptions (see Domingo et al., 2015 for a summary of the literature on quotas).

Several studies emphasise opportunities for women’s leadership created by processes of decentralisation. Sudarshan and

Nepal

Bisht (2006) argue that, in India, decentralisation with reservation (one-third quota in the Panchayati Raj institutions) has provided a space for women in local governance.

The presence of strong women’s civic movements and leadership can support and increase the power/influence of women in formal political leadership positions. Tripp’s (2001) study of the Ugandan women’s movement found the very existence of an independent women’s movement enabled women within Museveni’s government to advocate for a women’s rights agenda.’

The ODI review finds only ‘thin’ evidence of the outcomes in women’s lives from all this leadership activity (which makes it even more important to look at other kinds of leadership, surely?), but does provide a few examples (an awful lot of them from Oxfam and its partners – kudos to them – here’s Oxfam’s own conclusions on the work). Here are a couple of tasters:

‘The engagement of the Women Leaders’ Network, a transnational advocacy group, with Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), an intergovernmental organisation, improved the latter’s accountability, responsiveness and openness to external participation, and resulted in the use of gender analysis in policymaking.

Members of the Uganda Coalition for African Women’s Rights persuaded the two main political parties to address key articles of the African Women’s Rights Protocol on reproductive health rights in their campaign manifestos.

In a widely cited article, Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004) compared the investments made by local gram panchayats in two districts (Birbhum, West Bengal; Udaipur, Rajasthan, n=265). One-third of village council head positions are reserved for women, with these being selected randomly by the state based on specific rules. Chattopadhyay and Duflo found panchayats headed by a woman were more likely to make policy decisions and allocations that reflect women’s interests (such as investments in drinking water and education).’

There is one other rather serious blind spot – apart from a couple of passing references, there is very little recognition of the importance of participation in faith communities as a forging ground for women’s leadership, which in my (limited) experience produces far more leaders than anything done by NGOs, political parties or just about anyone else. Nor, in contrast, is their much on the role of faith and religion in undermining women’s participation. Shame. And odd, since there’s plenty of discussion of the role of faith and faith groups in the Pathways of Empowerment project (which is cited elsewhere in the paper). Could the ODI authors have had their secular blinders on? – wouldn’t be that unusual for the aid biz.

Supporting women’s local level participation and informal leadership is crucial because it is at this level that many of the decisions that affect women’s lives are being made – women’s influence often takes place through informal mechanisms such as self-help groups, women’s rights organisations and networks, community groups and cooperatives (where leadership is often ‘grown and matured’), which are typically missing from measures of, and interventions to increase, women’s participation and influence in decision making. More needs to be done here, and the first step would be to broaden the understanding of leadership underpinning this paper.

[thanks to Emily Brown, Caroline Sweetman and Laurie Adams for their comments on the draft – blame them for this being so long....]

May 26, 2015

How does Gender change the way we think about Power?

I can’t attend the next get together of the Thinking and Working Politically network in Bangkok next month because of a prior

Gender and Power. Discuss.

commitment to speak at DFID’s East Kilbride office (ah, the glamour of the aid biz….). Apart from missing out on the Thai food, it’s also a shame because they are focusing on an area I’ve previously moaned about – the absence of gender from a lot of the TWP/Doing Development Differently discussions.

Ahead of Bangkok, some of the participants have fired some useful preemptive shots. Tomorrow I’ll review an ODI survey on aid programmes promoting women’s leadership. Today it’s the turn of the Developmental Leadership Program, which has just published an interesting, if tantalizing, 6 page ‘concept brief’ on Gender and Power by Diana Koester.

Koester argues that a gender lens can add a lot to the TWP’s analysis, but also vice versa – we need more thinking about power and politics in gender discussions. Some excerpts:

‘Donors have largely neglected ‘gender’ in their efforts to understand power relations in partner countries. In particular they are often blind to the ways in which power and politics in the ‘private’ sphere shape power relations at all levels of society; the ways in which gender hierarchies mark wider economic, political and social structures and institutions; and the opportunities for peace and prosperity emanating from feminized sources of power. By addressing these blindspots, a focus on gender can significantly enhance donors’ insights into power dynamics and their ability to ‘think and work politically’ overall.’

‘This paper addresses three main questions: What is power and how can a gender perspective help us understand it? What is gender and how can a power perspective help us understand it? What policy and operational messages follow from a focus on gender and power?’

There’s a nice box on how different usages of ‘gender’ translate into views of power

and some excellent short case studies. Take this from Malawi on gender, power and mining:

‘A 2012/2013 Political Economy Analysis of mining in Malawi found that women’s specific priorities were systematically neglected in relevant decision-making. This was due to the power of male traditional elders over other individuals in the community, particularly women. For example, investors asked a community affected by mining whether they would prefer to receive cash compensation for relocation or to have houses built for them. Women said they would rather have houses, fearing that men would receive the cash and misuse it on unrelated acquisitions like buying cell phones, bicycles, spending on other women etc. However, when a woman got up to voice this viewpoint during a meeting, traditional authorities immediately commanded her to sit down and declared that “no woman would speak in front of men as women had no cultural standing to give an opinion on the matter”.’

I particularly liked this on how gender even shapes the understanding of power itself:

‘Our understandings of power may themselves be the result of men’s power over women. This is because power has been conceptualized by, and hence from the perspective of, privileged men. Feminist scholars have argued that our concepts are therefore derived from a masculine life experience “conceived as inhabited by a number of fundamentally hostile others whom one comes to know by means of opposition (even death struggle) and yet with whom one must construct a social relation in order to survive.” This leads to the concept of power as power-over.

We may be neglecting women’s specific forms and sources of power. Some feminist scholars suggest that women’s roles as carers and mothers lead in an opposite direction from the hostile world of masculine experience. Rather than in opposition, women construct themselves in relation and continuity to others. Rather than to dominate, the purpose of women’s activity is often to build capacity in others. This suggests an alternative conception of power as a specific kind of power-to: “the capacity to transform and empower oneself and others”. While this concept may risk homogenizing and essentializing women it can shed light on forces for change that may otherwise be neglected.’

But what about the so whats – the implications of this analysis for people working in governance, and the TWP crowd? Here I don’t think the paper quite nails it. The closest to an answer comes with an excerpt from one donor (Sweden’s SIDA) guide to power analysis:

‘Sida’s guide to power analysis provides an extensive menu of issues that power analysis might tackle. This includes several explicitly gender-related questions:

• How does gender intersect with the distribution of formal and informal power in society in terms of the public sphere (political institutions, social institutions, rule of law, the market and economy) and the private sphere (domestic life and family, intimate relations)?

• What can be said about both the situation of women in general and about particular groups of women (such as women who do not cohabit with men, whether single mothers, widows, non-married women) as well as about particular groups of men who may be disadvantaged by dominant ideas of masculinity?

• What can be said about both the situation of women in general and about particular groups of women (such as women who do not cohabit with men, whether single mothers, widows, non-married women) as well as about particular groups of men who may be disadvantaged by dominant ideas of masculinity?

• Is legislation gender neutral, or do particular laws reinforce and sustain subordinate or discriminated gender roles?’

But hopefully, the Bangkok meeting will get a lot further into the ‘so whats’. Fingers crossed.

May 25, 2015

Links I Liked

Lots of people in Financing for Development mode in the run up to the Addis summit:

Finance flows to Africa: From 1990-2012, total rose from $20bn to $120bn; Aid as % of total fell from 62% to 22%

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank; Silk Road Fund; BRICS Bank: how China is transforming global development finance

UK election post mortem (continued)

Britain resigns as a world power, according to the Washington Post

Alex Evans wonders where Labour can turn to find its vision thing

The art of spin. You’re Peabody Energy, a coal giant getting whacked on Climate Change. So why not rebrand yourself as a poverty warrior?

A grim killer fact (literally): “As things stand more than 62 workers will die for each game played during the 2022 Qatar World Cup tournament.”

Horribly fascinating: interactive graphic of homicide rates around the world.

Justified nepotism: another powerful, moving film on girls’ right to education, free of abuse, made by some of the girls in question, and my sister in law, Plan International’s Mary Matheson

May 24, 2015

Got any technical problems, glitches etc with this blog? If so, speak now

Dear FP2P readers, I gather you’ve had a few problems with stuff like sending comments, but now I have a keen new webmeister ready and eager to sort out glitches and improve the blog. To help him out, could you  please feed back via the comments page (if you can), or twitter/email (dgreen[at]oxfam.org.uk) on:

please feed back via the comments page (if you can), or twitter/email (dgreen[at]oxfam.org.uk) on:

a) stuff that doesn’t work, eg posting comments, seeing the post clearly on your screen (please tell us which device you are using and send us a screengrab) or any other bugbears. Particularly interested in how you find reading it on mobiles and tablets, as that’s where everyone (except me) is heading.

b) things you would like to do but can’t

c) anything else you think would improve the blog

We’re not asking re content for the moment (that’s my responsibility, not the webmaster’s) – will do a survey on that later in the year. So just the techie stuff please

ta

Duncan

May 21, 2015

Is ‘give them land rights’ enough? Taking the temperature of the global land debate

A bunch of students and academics from Sheffield University had what sounds like a fun time at last week’s big  global

meeting on land. George Barrett, Yoshabel Durand, Tom Goodfellow, Vremudia Irikefe, Mikael Omstedt, Edward Searight, Julie Shi, Deborah Sporton and Nguyen Vo report back.

global

meeting on land. George Barrett, Yoshabel Durand, Tom Goodfellow, Vremudia Irikefe, Mikael Omstedt, Edward Searight, Julie Shi, Deborah Sporton and Nguyen Vo report back.

Last week, dispersed among 700 participants at the International Land Coalition’s global forum in Senegal sat nine of us from the University of Sheffield – seven students and two academic staff. Surrounded by throngs of NGOs fighting for land rights around the world, our presence was part of a university programme providing opportunities for students to engage as international policy analysts. We were basically part of the comms team: blogging, interviewing ILC members and tweeting frenetically to extend the reach of the debates taking place. As observers of the whole event rather than participants with an agenda – or journalists dipping in for one session – we got a good feel for the general state of the debate on land.

Concern about ‘land grabbing’ has reached fever pitch, particularly with respect to Africa, but the discussion showed that this is far more complex than big multinationals seizing land from smallholders. In fact, in many cases the land grabbers are national elites who purport to protect their people from ‘foreign’ grabbers: ‘the one who is looking for the needle has their foot on it’, in the words of a Malian participant. Meanwhile, efforts towards the restitution of land for ‘indigenous peoples’ (a

Early champion of land grabbing

contested term in itself) were perceived by some as just another form of land grab, veiled in appeals to traditional legitimacy but with insufficient attention to justice and transparency. This concern was raised in relation to the forced resale of ancestral lands in Scotland, as well as Ghana.

In many parts of the world, land is so central to the economy, politics and cultural life that it can be seen as the central problem of development itself. ‘He who controls the land will control power’, in the words of one participant – and it is indeed usually ‘he’. Despite the prominence of ‘women’s land rights’ at the event, when it came to debates on one of the dominant concerns of the conference – business and how it can produce more inclusive outcomes – women and their voice were often absent.

There was also relatively little attention to gender as opposed to ‘women’, despite years of effort to refocus on inter and intra-gender dynamics rather than just females. Meanwhile, several decades of legalising women’s access to land have starkly revealed that cultural norms and practices are much more important than laws. A study from India, for example, demonstrated that progressive land reforms to facilitate women’s inheritance had little effect because women feared the social stigma they would face if they actually claimed this right. In another case, it was found to be more effective to shift the norms of use associated with customary land rather than create new ownership rights for women.

This disillusionment with legal reforms percolated far beyond the gender discussion: the whole conference reflected the gradual collapse of any certainty that giving people titles to land will result in social justice. Echoing the recent recognition among development policy types of the need to go beyond the idea that ‘institutions matter’, this was vividly brought to life in discussions on both gender and indigenous rights. What good, for example, is providing indigenous groups with special rights to buy the land they inhabit if this is likely to send them spiralling into debt, sometimes resulting in rushed re-sales of land that leave them worse off than before? A representative from Ecuador also pointed out that increased access to land for indigenous groups can come with pressure to use that land for commercial purposes, undermining customary practices and in some cases negatively affecting familial and community relations.

The overall impression was therefore of the urgent need to move beyond the assertion of ‘rights to land’, which in its bald,  unqualified form has become relatively meaningless. One approach to this problem at the conference was to distinguish between people’s historic rights to tend and inhabit land and what some speakers termed ‘real rights’ to land (which basically translates as rights for developers/foreign investors). While this was meant to facilitate the coexistence of smallholding and agribusiness, for some of us the language was worrying. It seems to suggest a two-tiered system, in which the rights of communities to use land they may have occupied for centuries will necessarily be trumped by superior rights for those with the resources to invest in growth-enhancing agriculture or real estate. More positively, however, one session showcased a ‘social tenure’ model for mapping the full diversity of relationships that exist between spatial units, supporting documents and people (individually or collectively) – the aim being to use this to help people articulate and claim more nuanced forms of tenure rights.

unqualified form has become relatively meaningless. One approach to this problem at the conference was to distinguish between people’s historic rights to tend and inhabit land and what some speakers termed ‘real rights’ to land (which basically translates as rights for developers/foreign investors). While this was meant to facilitate the coexistence of smallholding and agribusiness, for some of us the language was worrying. It seems to suggest a two-tiered system, in which the rights of communities to use land they may have occupied for centuries will necessarily be trumped by superior rights for those with the resources to invest in growth-enhancing agriculture or real estate. More positively, however, one session showcased a ‘social tenure’ model for mapping the full diversity of relationships that exist between spatial units, supporting documents and people (individually or collectively) – the aim being to use this to help people articulate and claim more nuanced forms of tenure rights.

If the need to deepen our understanding of rights to land was an overriding theme, what were some of the omissions in the debate? One was a discussion of food sovereignty, which in recent years has animated debate in policy and academia, but was virtually absent from the agenda. As opposed to food security, which is largely about facilitating market solutions to hunger, food sovereignty involves bottom-up, farmer-first solutions to food production. Again, this absence reflects the tendency of land discourses to focus on endowments, without sufficient attention to people’s entitlements – their capacity to actually use and benefit from what they can legally claim.

A further striking omission was the question of urban land. We were told by the ILC that they had approached member organisations for sessions on urban issues, but none came forward. This is worrying given that the urban poor are some of the most vulnerable to eviction as the value of prime urban land soars (often driven by land titling programmes!). The omission likely reflects the fact that people still tend to see ‘urban issues’ as being those associated with service delivery, housing and infrastructure, when land actually underpins all of these. Moreover, when a participant asked about potential for urban agriculture in one session, the Ugandan government panellist simply replied that ‘people cannot farm in Kampala’ – a blatant untruth that cut off debate on an important issue.

So, where does all this leave the debate on land? Despite the great range of successes and failures showcased from across the world, there was scant sense at the forum of a way ahead beyond the need to replace the teetering paradigm of secure legal title. Shoots of a new direction are apparent, however, in the form of moves to embrace the progressive potential of customary land by tackling injustices in current usage from all angles, rather than depending on legal reforms built on individualistic principles.

By the way, Sheffield University is advertising for a Director/Research Chair in International Development. Closing Date 3rd June.

May 20, 2015

What do we know about the long-term legacy of aid programmes? Very little, so why not go and find out?

We talk a lot in the aid biz about wanting to achieve long-term impact, but most of the time, aid organizations work in a time

Why not come back in a decade?

bubble set by the duration of a project. We seldom go back a decade later and see what happened after we left. Why not?

Everyone has their favourite story of the project that turned into a spectacular social movement (SEWA) or produced a technological innovation (M-PESA) or spun off a flourishing new organization (New Internationalist, Fairtrade Foundation), but this is all cherry-picking. What about something more rigorous: how would you design a piece of research to look at the long term impacts across all of our work? Some initial thoughts, but I would welcome your suggestions:

One option would be to do something like our own Effectiveness Reviews, but backdated – take a random sample of 20 projects from our portfolio in, say, 2005, and then design the most rigorous possible research to assess their impact.

There will be some serious methodological challenges to doing that, of course. The further back in time you go, the more confounding events and players will have appeared in the interim, diluting attribution like water running into sand. If farming practices are more productive in this village than a neighbour, who’s to say it was down to that particular project you did a decade ago? And anyway, if practices have been successful, other communities will probably have noticed – how do you allow for positive spillovers and ripple effects? And those ripple effects could have spread much wider – to government policy, or changes in attitudes and beliefs.

As always with some MEL question that makes my head hurt, I turned to Oxfam guru Claire Hutchings. She reckons that the practical difficulties are even greater than I’d imagined: ‘even just understanding what the project actually did becomes challenging in closed projects. Staff and partners that worked on the project are usually funded by the restricted funding. Once that ends, they move on, and without them it is incredibly difficult to get at what really happened, to move beyond what the documentation suggests that they would do or did.’

In the long run, not all aid projects are dead

And Claire thinks trying to look for attribution is probably a wild goose chase: ‘I do think we need to manage/ possibly alter expectations about what we can realistically consider through an evaluation once a project has been closed for some time. Trying, for example, to understand the change process itself, and the various contributing factors (of which the project may be one), rather than focusing on understanding/ evidencing/ evaluating a particular project’s contribution to a part of the change process.’

My colleague John Magrath, who acts as Oxfam’s unofficial institutional memory, reckons one answer is to make more use of historians and anthropologists, who are comfortable with a long-term perspective. He also points out that the level of volatility looks very different from a donor perspective to that of a local organization – donors come and go, but local organizations are often much more stable over time, so partly (echoing Claire’s point), we should just try and understand the origins of their success, and not worry so much about taking some sort of credit for it.

Tim Harford argues in Adapt that successes usually rise phoenix-like from the wreckage of earlier failures, and that applies to the aid business too. How do we know when people have acquired skills in some long defunct and abandoned project and then applied them somewhere else with huge success?

Or the same project can move from initial failure to subsequent success, as Chris Blattman recently wrote about in a US social programme. If your MEL stops with the project, you may never even find out about that eventual success.

The point of doing all this would be to explore how the focus or design of particular projects affects their long-term impact, and so shape the design of the next generation. Any foundations out there interested in taking up the challenge?

The good news is that others are already thinking along these lines – I just got this from VSO’s Janet Clark:

‘As a starting point we have commissioned an evaluation one year after we have closed down all our in–country programmes in Sri Lanka. Although this is only a small step in the direction of understanding sustainability we are also looking at the feasibility of assessing impact over a longer period across other programmes.

The evaluation questions centred around how local partners defined capacity and what contribution VSO volunteers made to

But how do you prove it?

developing capacity, alternative explanations for changes in organisational capacity, unanticipated consequences of capacity development and to what extent capacity development gains have been sustained. There was also an exploration of how change happened such as what are the key factors in whether or not capacity development was initially successful and subsequently sustained and what is uniquely and demonstrably effective about capacity development through the placement of international volunteers.

After one year of closing our country office there were some practical logistical challenges of carrying out an evaluation – we received valuable support from former staff but they were busy with new jobs and projects. Former partners sometimes struggled to remember the details of some of the interventions that dated back ten years and in some instances key partner staff had moved on. These factors meant that the evidence trail was sometimes weak or lost but this was not always the case.

We are now trying to identify good practice in this area so I would be very interested in hearing of others experience.’

Over to you

Update: a lot of great ideas and links in the comments section – make sure you read them

May 19, 2015

Oh dear. Another unreadable European Report on Development. Good stats on finance (FFD) though.

Here I go again. Sorry. Europe is home to some of the world’s most interesting and innovative research and action on aid and  development, littered with smart thinktanks, thoughtful academics, and reflective practitioners. So it would be great to create some kind of intellectual counterweight to the US-based dominance of the World Development Report and others. Why then is the European Report on Development so invariably disappointing?

development, littered with smart thinktanks, thoughtful academics, and reflective practitioners. So it would be great to create some kind of intellectual counterweight to the US-based dominance of the World Development Report and others. Why then is the European Report on Development so invariably disappointing?

Let’s start with the title of this 5th ERD: ‘Combining finance and policies to implement a transformative post-2015 development agenda’. Enough said.

After that if follows the usual ERD format, which I summarized in a post on the 2013 ERD:

‘What you get is a decent overview of progressive thinking on inequality, migration, trade, domestic resource mobilization and the role of aid. And a lot of developmental platitudes: the ‘key conclusions’ include ‘a transformative agenda is vital’, ‘national ownership is key’, ‘the children are our future!’ (OK, I made that last one up).’

Have things improved? ‘Fraid not. Here’s how the press release summarizes the ERD 2015’s key messages.

‘A key message emerging from the report is that success will be determined by the way policies and finance are used to implement a transformative post-2015 development agenda, and that a lack of funds will not be the constraining factor in achieving the objectives. Based on existing evidence and specific country experiences, the ERD 2015 shows that finance seldom reaches the intended objectives unless the right policies are in place. To implement a transformative, post-2015 development agenda needs the right combination of finance and policies.’

Yes, that’s the press release. Hold the front page – you need cash and the right policies. Who would have thought it!

The one section that woke me from my torpor was the number crunching on financial resources:

The one section that woke me from my torpor was the number crunching on financial resources:

‘Finance options have changed

FFD options have changed dramatically by country income grouping, and over time. For example, consider the following financial flows (expressed in 2011 constant prices):

Domestic public revenues (tax and non-tax revenues) rose by 272%, from $1,484 billion (bn) in 2002 to $5,523 bn in 2011

International public finance (net ODA and Other Financial Flows (OOF)) rose by 114%, from $75 bn in 2002 to $161 bn in 2011

Private domestic finance (measured as Gross Fixed Capital Formation by the private sector, less FDI) rose by 415%, from $725 bn in 2002 to $3,734 bn in 2011

Private international finance (net FDI inflows, portfolio equity and bonds, commercial loans and remittances) rose by 297%, from $320 bn in 2002 to $1,269 bn in 2011.

Thus, since the 2002 Monterrey Consensus, in real terms (2011 dollars) developing countries have had access to an additional $0.9 tr in private international finance, $3 trillions (tr) in private domestic finance and $4 tr in public domestic revenues. Public international finance increased by just under $0.1 tr (and the total is now less than 1.5% of the total resources available). Figure 1 depicts the evolution of finance flows to developing countries.

The data shows that domestic public resources have grown rapidly and are the largest source of finance for all country income groupings. International public finance has also increased but is declining in relative importance. Domestic private finance has shown the fastest growth, but is still much lower (as a percentage of GDP) in LICs than in lower middle-income countries (LMICs) and upper middle-income countries (UMICs), with rapid transformations continuing. International private finance has been highly volatile compared to the other flows. Innovative finance is promising but is yet to take off on a large scale. These trends set the context and also present a number of key challenges that need to be addressed in the post-2015 development agenda and FPFD. For example, it is clear that there is both a need to think more about public resources ‘beyond aid’ and also to consider new approaches to ODA.

The composition of finance evolves at different levels of income

Figure 2 shows that as countries move towards higher incomes, they tend to experience: (a) declining ratios of aid-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP); (b) increasing tax-to-GDP ratios (stabilising when countries approach LMIC levels), and within this, increasing shares of tax from incomes and profits and notably goods and services, but declining shares of international trade tax revenues; and (c) increasing private investment-to-GDP ratios.’

I had a decent exchange with the ERD team over my critique of the 2013 report (in the comments), so anyone care to leap to the report’s defence this time around, say what I’ve missed etc? I should confess that I’ve only read the 21 page executive summary (not sure they quite understand how executives work, There may be some buried gems in the full 377 page report – but in that case, why are they buried?!

Here endeth the rant.

May 18, 2015

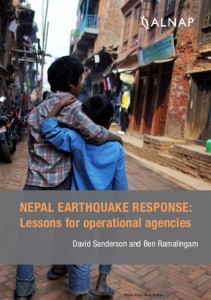

What can we learn from a great example of high speed policy response to the Nepal Earthquake?

For a while, I’ve been arguing that policy wonks need to grab the windows of opportunity created by shocks, scandals and  crises, producing reactions, research and proposals in the immediate aftermath of such a ‘critical juncture’. For example, we know there are going to be floods in Somerset or Pakistan at some point in the next few years, so in advance, why not get a response paper summarizing the evidence on the links to climate change 90% done and set up a network of scientists, business people, faith leaders, NGOs that are all ready to go when disaster strikes? That way we can have a significant response out there within days, just when policy makers, media etc are desperately looking for explanations and new ideas.

crises, producing reactions, research and proposals in the immediate aftermath of such a ‘critical juncture’. For example, we know there are going to be floods in Somerset or Pakistan at some point in the next few years, so in advance, why not get a response paper summarizing the evidence on the links to climate change 90% done and set up a network of scientists, business people, faith leaders, NGOs that are all ready to go when disaster strikes? That way we can have a significant response out there within days, just when policy makers, media etc are desperately looking for explanations and new ideas.

Now Ben Ramalingam and David Sanderson have done just that on the Nepal earthquake. Nepal Earthquake Response: Lessons for operational agencies, published by the ALNAP network provides a 25 page summary of the most relevant lessons learned from previous earthquakes and urban disasters, (crucially) all contextualised to what is already happening on the ground in Nepal, with links to websites, key documents etc.

In the report, 17 ‘lessons’ get a page or so each. They are:

Strategy and management

1. Work with and through national and local actors, structures and networks.

2. Use the extensive preparedness planning that has already taken place.

3. Ensure that capacity development is seen and used as a vital form of aid.

4. Coordination is essential and must be tailored to the Nepali context.

4. Coordination is essential and must be tailored to the Nepali context.

5. Support pre-existing goods and service delivery systems.

6. Logistics are critical and demand the effective brokerage of international expertise.

7. Recognise the regional nature of the response.

8. Understanding and anticipating population movements are essential.

9. Pay special attention to marginalised, hidden and vulnerable populations, especially in urban areas.

Technical delivery

10. Assessment is the foundation for appropriate response.

11. Use digital technology and engage in two-way communication with affected communities.

12. Use cash-based programming linked with market analysis.

13. Get ready for the monsoon with temporary durable shelters such as high-quality waterproof tents.

Getting water flowing

14. Rebuild settlements safely to be ready for the next earthquake.

15. Debris management: urban rubble presents a challenge, but also a resource.

16. Health and WASH needs change quickly and require continuous assessment and adaptive responses.

17. Emergency education efforts should address both immediate and long-term needs.

As an example, here’s the page for Lesson 7:

‘Recognise the regional nature of the response.

The earthquake response has a strong regional dimension, with India and China in particular playing a central role. International actors should seek to align and coordinate with and mutually support these actors. Six members of the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network have already responded: NSET Nepal, SEEDS India, Mercy Malaysia, PGVS India, Doctors for You India and Dhaka Community Hospital Bangladesh, with coordination taking place via Nepal Quake Hub.

The efforts of key regional actors should be worked with and integrated at all levels. In Myanmar after Cyclone Nargis the creation of the Tripartite Core Group as an ad hoc coordinating body by the government, UN and Association of Southeast Asian Nations allowed for greater international-regional collaboration in response and recovery. Similar efforts should be made to integrate regional players into the NEOC system in the Ministry of Home Affairs. This should also provide a strong platform for regional engagement in local levels of operational management, for example, by bringing representatives of regional actors into the various clusters, leading to the better use of resources and a reduced coordination burden at the district and local levels.’

This came out within two weeks of the earthquake, and shows just how good humanitarian types can be responding to events. Speaking to one of the authors, I get the sense that this is an intensive ‘real-time’ process, with the team doing a lot of interviews and reviewing a lot of material in a very short time, and getting feedback from frontline responders. Lots to learn here for those of us working in long term development or advocacy.

This came out within two weeks of the earthquake, and shows just how good humanitarian types can be responding to events. Speaking to one of the authors, I get the sense that this is an intensive ‘real-time’ process, with the team doing a lot of interviews and reviewing a lot of material in a very short time, and getting feedback from frontline responders. Lots to learn here for those of us working in long term development or advocacy.

Two suggestions though – could the authors and ALNAP think about making this a living document/website, which could evolve as new ideas, documents and websites emerge in the weeks after the quake? That would make for a genuine real-time learning process.

And looking at the ALNAP website, the contextualised lessons papers are clearly very popular, but they don’t seem to be published after every crisis – so some big crises (like Haiti or Haiyan) see generic lessons being circulated. But given the importance of context, perhaps this kind of learning process should become more routine in the humanitarian sector?

May 17, 2015

Links I Liked

The only possible response is ‘thankyou to all involved’ for this wonderful pic (coming soon to a powerpoint near you) [h/t  Damian Hughes]

Damian Hughes]

To end extreme poverty, we must also address extreme affluence.’ Advice from some dangerous radicals (aka faith leaders) on how to end poverty

Economics is reinventing itself as an empirical discipline, argues Barry Eichengreen. Whatever next?

Some powerful killer facts here: 5 flashing warning lights on the dashboard of the global humanitarian system

Have we lost the ability to monotask? The steady fall in attention span (from 3 minutes average to less than one) over the last 10 years. Sorry what was that?

Is the aid business guilty of ‘intellectual dumping’ by swamping developing countries with advice, technical assistance etc and squeezing out local wisdom?

In Turkey, even statues of Ottoman princes are taking selfies

In Turkey, even statues of Ottoman princes are taking selfies

The data revolution should change the balance of power, but currently it has been hijacked by the techies. Great evidence-based rant from Alex Cobham

Strong Girl. You may not agree with all the gender messaging in ONE Campaign’s latest video and action, but it sure beats a bunch of white rock stars doing Do They Know its Christmas? Or (far far worse), the sight of NATO foreign ministers singing ‘We Are the World’ at a summit in Turkey last week [h/t Zeynep Tufecki]

May 14, 2015

If Complexity was a person, she would be a Socialist. Jean Boulton on the politics of systems thinking.

Jean Boulton (physicist, management consultant and social scientist, right) responds to Owen Barder’s Wednesday post on thinking of  development as a property of a complex adaptive system.

development as a property of a complex adaptive system.

I’d like to go a bit further than Owen on the implications of complexity for how we understand power and politics. It is generally the case that the powerful get more powerful and the big get bigger. We know this through bitter experience, captured in complexity language by the notion of ‘positive feedback loops’ which equate to the economists’ ‘increasing returns’. In general there is no reason to expect that economies will self-regulate and find a ‘natural’ balance. Even forests, if left to themselves for long enough, reduce in diversity, increase in efficiency and become ‘locked in’ to ecological patterns that are hard to invade and change and can easily collapse (see below, left). Despite the popularity of the phrase ‘complex adaptive systems’, complex systems do not always adapt.

Instead, complexity suggests that if we want economic development that equalizes power, reduces inequality and incorporates longer-term environmental goals, there is a need for some sort of regulatory processes to counter the seemingly inevitable coalescing of power and wealth in fewer and fewer hands. Otherwise the rise out of poverty is linked more to growth than to development (development meaning a qualitative change in shape and form of the economy rather than a quantitative change – you can obviously have both). And an economy that is growing can in fact take our attention away from underlying structural exacerbations of inequality. Growth cannot go on forever, as land, water and minerals are consumed – not to mention the impact on climate change – but growth can mask just who captures the bulk of resources and can exert control over governments, markets and societies.

This move away from a balanced self-regulating system is different, I would argue, to the behaviour of ant colonies and flocks of birds. Their self-organising processes are specific to the task. They can merely rearrange the deck chairs, so to speak; they can fly around buildings or build ants’ nests that adapt to local conditions, but they don’t in general change their nature and adopt new behaviours. Nothing new emerges, nothing co-evolves.

Sometimes, something more drastic and disruptive is needed. In situations which have very locked-in political and social factors, the focus needs to be on how to break the deadlock, perhaps with high level political interventions and sanctions rather than more gentle adaptation. No use approaching economic development in Palestine with an adaptive mindset. Equally, if the situation is chaotic, like say in South Sudan, then finding ways to build on (any) emerging shoots of political stability is likely to be a first priority.

So, I think the ways to intervene are not necessarily about improving the ‘capacity to adapt’. Sometimes it is also about opposing the powerful who want to reduce diversity. Sometimes it is about slow systemic change, but sometimes it is about seizing opportunities, building on success or on pockets of best practice. And sometimes it is about pushing all the levers in the same direction; or influencing the one key person or focusing on a key underlying issue without which all else well fail; or doing all of these at different times.

I’m also more keen on analysis than Owen. I think you have to start with the historical background (which sets a sort of complex baseline and identifies the strength and form of current social and political and economic patterns), understand the wider contextual features and, indeed, identify ‘missing ingredients’ and ‘binding constraints’ together with opportunities and future possible ‘critical junctures’. Analysis has to have a time dynamic, and be systemic, but I think it is vital. Then, true, you have to move into action and try things out without expecting to prove exactly what is the best strategy or what it will achieve.

We’ve covered power, but, with last week’s elections in the UK fresh in mind, what about the politics of Complexity? At least if she was interested in social and economic justice, Complexity would never stand for election for a party based on a ‘free market’ ideology because, as discussed above, positive feedback loops lead, almost inexorably, to the big getting bigger and the powerful increasing in power. The reduction in numbers of small banks, the constant pushing of legal boundaries, the size of bankers’ bonuses show what can happen in a deregulated market. Power and money give the means to dominate, to win the advertising campaign, to push governments, to squeeze supply chains. There is no such thing as a free market.

Instead, I would argue that Complexity is more of a socialist than anything else (a very Green one though – she

Red, green and complex

understands the need to consider long-term consequences to the system of which we are a part). Complexity understands market failure. She does not take the naïve view that self-organizing processes are shaped by some sort of ‘natural law’ and can be trusted to provide the ‘best’ outcome; she understands the importance of governance and ways of upholding the needs of the less powerful, the poor, the longer-term and the environment. This is not to suggest that she would impose a top-down model of governance dreamed up on a plane by consultants and lawyers and plopped fully formed onto a developing country. Rather she sees the need to facilitate the emergence of socially-owned processes of governance and civic empowerment, and to build on those practices that already exist.

There’s more. Complexity is community-minded (would balance freedom with responsibility), keen to work at the appropriate scale, keen not to impose solutions, but to work with enhancing and protecting what is already there. She is passionate about embracing diversity and brave enough to wander well outside any narrow remit to identify blockages, join things up and say the unsayable. She understands that you have to work from the smallest household to the biggest government or corporation – and back again -to enhance the conditions for economic development in a way that leads to equality and sustainability.

Jean’s book, ‘Embracing Complexity: Strategic Perspectives for an Age of Turbulence’ (written together with Peter Allen and Cliff Bowman) will be out this summer, published by Oxford University Press.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers