Duncan Green's Blog, page 163

June 9, 2015

What future for Development Advocacy? Three Paradoxes and Seven Directions

Oxfam America’s head of policy and advocacy, Paul O’Brien wonders if he’ll still have a job in a few years, based on his  remarks to a recent Gates Foundation gathering on the evolution of Policy and Advocacy work.

remarks to a recent Gates Foundation gathering on the evolution of Policy and Advocacy work.

A century from now, how will development historians characterize our policy advocacy in a post-2015 world? In a year that aims to transform development finance and goals, policy advocates have to grapple with three paradoxes:

The places where we have the most influence show the least appetite for change;

As our slice of the development financing pie gets smaller, it is becoming more important; and

The only thing worse than not being taken seriously, is being taken seriously.

The environments where we have the most access, influence, advocacy resources and political space are in Northern political capitals. And so we challenge politicians in Brussels and Washington, because we know how to do it, and because we can. For our advocacy hammer, Northern policy makers make a great nail.

Unfortunately, those northern politicians aren’t listening to our hammering. An excellent 2009 study, Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses and Why found that, over the previous decade, the majority of lobbying efforts failed, and 19 out of 20 times, it didn’t matter how much money lobbyists threw at the problem. By contrast, the study found, efforts to defend existing policies often succeeded (so our work to defend aid and stop policy reforms that are bad for the poor are frequently our most successful).

Meanwhile, all over the developing world, and especially in countries where so many of the extreme poor are—from China and India to the more fragile states in Africa and Central Asia—there is much more “elasticity” in economic policy and political space, for better and worse–just look at the countries with significant changed rankings in freedom, corruption, and open budgets. At the same time, global corporations are waking up to the profit implications of being good or bad planetary citizens, which helps explain the success of Behind The Brands.

Over the next 15 years, it will become existentially clear to many global advocacy organizations that we must put more effort where the real elasticity is. We are going to have to develop influence in Abuja, Delhi, Nairobi, and Addis Ababa, and with Coke, Petrochina, and Barclays Bank.

Does that mean we need to close up shop in Washington, London and Brussels? No. But as developing country governments and corporations become primary targets (the ones whose policies we need to influence), we will increasingly work with northern political actors as secondary targets (where they still have influence over our primary targets). But if we keep hammering away solely at Northern nails in the hope of remaining relevant to a post-2015 world, we are fooling ourselves and very few others.

The most ubiquitous factoids going into the big Financing for Development summit in Addis Ababa next month will surely be those that show global ODA diminishing as a proportion of public international finance, which in turn is being increasingly dwarfed by domestic resources.

Paradoxically, as the money we control (our own resources) and help to shape (e.g. ODA) become a smaller part of the pie, how each dollar gets used may have a much greater impact on the lives of the poor by 2030.

Take Mozambique which languishes at 178 on the Human Development Index, behind Liberia, Afghanistan and Haiti. They have discovered 250 trillion cubic feet of gas off their shorelines, which could provide a third of their fiscal revenue. Development advocacy, properly targeted, may help to shape how much of that wealth gets exploited or left in the ground. It may expose corruption and incentivize political institutions to manage this new national wealth better, it could meet critical humanitarian gaps in health and education until the domestic resources start to flow.

Ethiopia (HDI rank: 173) hosts the Financing summit, and the government will be telling a story of economic growth not aid. They plan to keep growing at 10% a year until they become a Middle Income country in ten years. The key variable will be the quality of that growth, and where its dividends are invested, and that may depend on the political space to self-correct when policies are misplaced. Considering the operating environment for civil society in Ethiopia, the space to flag issues to be considered for self-correction is in jeopardy. And that raises a last paradox.

Wilde’s Paradox (doesn’t apply)

Wilde’s Paradox (doesn’t apply)

Oscar Wilde once wrote “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” For development advocates today, the reverse is true: the only thing worse than not being talked about, is the new attention we are getting.

As USAID increasingly embraces governance work and the importance of local institutions and solutions, they are getting kicked out of countries like Russia and Bolivia for having an increasingly political agenda. In India, the government has frozen Greenpeace’s bank accounts, and has put the Ford Foundation on a watch list.

As development work becomes as much about shaping power as transferring resources, about strengthening political will as much as institutional capacity, about incentives as much as innovation, this paradox may be the most troubling of all.

Seven ways to evolve our work:

The Hammer, Lever and Wilde Paradoxes will force us to get more sophisticated in our (1) language, (2) identity, (3) evidence, (4) incentives, (5) partnerships (6) theories of change, and (7) proof of impact.

Language: If the words we use are too euphemistic, we will fool ourselves that the poor have no politics, and nor do we. If are too blunt, we will lose our space to operate.

Identity: Northern-funded and -controlled development institutions will have to change who “we” are if they are to retain the legitimacy, skills and space they need to play a useful role. If we rebalance our power and resources and evolve our identity, we could become a truly worldwide influencing network. If we don’t, our political relevance will dissipate.

Evidence: Local elites will give us more space as technical experts than as opaquely-financed ideologues. When we do take explicit sides and lobby in the South, the more we can ground our positions on solid empirical research, the higher the costs of sanctioning or ignoring our work.

Incentives: For the last 30 years, “influencing governments” in the developing world meant developing non-confrontational “partnerships” to deliver services and convince governments to adopt our innovations. There were few incentives for donors, operational NGOs or government aid agencies to confront governments in developing countries or hold them accountable, if it meant risking access or getting evicted. The incentives and ways of working within our organizations will have to change if we are to get serious about influencing in non-permissive environments.

Partnerships: As we shift our southern partnerships from apolitical implementers to those who seek to shape policy and  politics, we must understand how civil society activism actually works and is perceived in many developing countries. Many governments already view local civil society as “the opposition in waiting”, and our support for them as a partisan statement that cannot be shrouded in development-speak. We will have to rethink our alliances, perhaps moving beyond formally constituted CSOs to the institutions and individuals that accompany the poor or create platforms for their political voice—religious and creative bodies among them.

politics, we must understand how civil society activism actually works and is perceived in many developing countries. Many governments already view local civil society as “the opposition in waiting”, and our support for them as a partisan statement that cannot be shrouded in development-speak. We will have to rethink our alliances, perhaps moving beyond formally constituted CSOs to the institutions and individuals that accompany the poor or create platforms for their political voice—religious and creative bodies among them.

Theories of Change: Being relentless about empowerment does not always mean being conspicuous. Deep theories of change permit political subtlety. The genius of the transparency movement is that its theory of change is so passive-aggressive. Which skeptical politician could begrudge a thirst for accurate data? Yet the underlying logic is profoundly political–that transparent data and empowered citizens can challenge governments to be more accountable.

Proof of Impact: As more work shifts from service delivery to influencing, the burden to demonstrate a “return on investment” for policy and advocacy work will only grow. As data and tech transform what is knowable, we cannot ask our publics and donors to “trust ” that we are delivering. The organizations that marry operational presence in the south with innovative technology and proof of influence will thrive while others will starve.

If collectively we are to be remembered a hundred years from now for having confronted and tackled the crises of our age—the pervasive extremes of poverty, climate and economic inequality, then we must confront these paradoxes and find new, more politically relevant ways to shape our world.

June 8, 2015

What happens when historians and campaigners spend a day together discussing how change happens?

Part of the feedback on last month’s post calling for a ‘lessons of history’ programme was, inevitably, that someone is already doing it. So last week I headed off to Kings College, London for a mind expanding conference on ‘Why Change Happens: What we Can Learn from the Past’. The organizers were the History and Policy network and Friends of the Earth, as part of its excellent ‘Big Ideas’ project (why haven’t the development NGOs got anything similar?) About 70 people, a mix of historians and campaigners. Great idea.

The agenda (12 UK-focussed historical case studies on everything from resistance to the industrialization of farming post World War 2 to municipal activism in Victorian Britain to why England (though not Scotland and Ireland) hasn’t had a famine since the 16th Century) was great, as was the format (panels, followed by table discussions, no Q&A).

A lot of the stuff I talk about on this blog seems completely obvious and standard for historians, for example the interaction  between social activism and ‘critical junctures’: Despite a century of civil activism by smoke abatement societies, it took the Great Smog of December 1952, which killed my grandmother along with 4-12,000 others, before the UK government passed the 1956 Clean Air Act.

between social activism and ‘critical junctures’: Despite a century of civil activism by smoke abatement societies, it took the Great Smog of December 1952, which killed my grandmother along with 4-12,000 others, before the UK government passed the 1956 Clean Air Act.

Ditto, the crucial importance of narratives and the ‘terms of debate’ in driving change and the interaction between agency (activists, leaders) and the underlying political, economic and demographic tides that shape the possibilities of change: only when the franchise was extended in the mid 19th Century could reform-minded municipal politicians get elected with a mandate to raise enough taxes to sort out appalling living conditions in Victorian cities.

For me, there was no great revelation, but a series of smaller ‘lightbulb moments’, including:

What if there is no historical precedent? Climate change campaigners often stress that we are in uncharted territory, so there is not much we can learn from history. But if you go back you will find similar examples of unprecedented changes in history – use of gas in warfare? Geneva conventions? So actually there are plenty of precedents for unprecedented changes. Cool, eh?

Asset-based approaches to activism: Several presentations on different aspects of the women’s movement made similar points. Especially before they got the vote, women were active in other channels – often in spheres traditionally seen as appropriate for women, such as nutrition and health (arguable, sometimes as ‘trojan horses’ for more radical change that was viewed as outside the proper sphere of influence for women). That focus on agency rather than exclusion reminds me of asset-based approaches to livelihoods that look at what people have/do, rather than what they lack.

Asset-based approaches to activism: Several presentations on different aspects of the women’s movement made similar points. Especially before they got the vote, women were active in other channels – often in spheres traditionally seen as appropriate for women, such as nutrition and health (arguable, sometimes as ‘trojan horses’ for more radical change that was viewed as outside the proper sphere of influence for women). That focus on agency rather than exclusion reminds me of asset-based approaches to livelihoods that look at what people have/do, rather than what they lack.

There are at least three different kinds of shock, requiring different approaches from campaigners:

a) Big, in your face events that drive change, such as wars and famines

b) Unforeseeable spikes that emerge without any obvious cause – a feature of complex adaptive systems (e.g. the Arab Spring)

c) Shocks that don’t lead to the expected changes, eg Global Financial Crisis

Competition for policy windows: when a new government or other window of opportunity opens up, it can be crucial to  get to the front of the queue. In France, Francois Hollande came to power committed to legalizing both assisted dying and equal marriage. He went with equal marriage first, was shocked by the Catholic backlash, and backed off further social reforms.

get to the front of the queue. In France, Francois Hollande came to power committed to legalizing both assisted dying and equal marriage. He went with equal marriage first, was shocked by the Catholic backlash, and backed off further social reforms.

But the conference wasn’t an unmitigated joy. I rapidly realized that a fair number of historians must have been in the archives/pub when academics got their class on how to communicate. Reading out papers in weird, stumbling, sing-song voices (doing it from your ipad just makes it harder, it seems); powerpoint karaoke (reading out overlong quotes on their slides, as if the audience is somehow unable to read). Heavy going.

The challenges of interdisciplinarity go a lot deeper than bad presentation – whole worlds of new, and unintelligible jargon; different ideas of what’s important (historians, like anthropologists, revel in detail); the struggle to understand the needs and priorities of another discipline (campaigners). Conclusion: we can’t just turn on the history tap and draw down lots of ideas – we’ll need to invest time and effort in getting to know each other, learn each others’ language etc. So good news that the organizers plan to continue to work together on this.

Most speakers insisted on numerous caveats and nuances and seemed to thoroughly disapprove of anything resembling an actual ‘lesson’. Indeed, they seem to love debunking any vaguely popular narrative (eg that World War Two had positive impacts on nutrition and inequality). That might explain the sense of being marginal that led to the setting up of History and Policy in the first place – nothing like saying ‘there are no general lessons, everything is context and time-specific, and only historians can talk with authority about anything in the past’ for ending up in a disciplinary ghetto. Conclusion: need to be clear that history is about looking for repeated patterns, not unearthing detailed blueprints – it should open up our imaginations and expand our sense of possible directions, not close them down.

Friends of the Earth talisman Jonathan Porritt wound up the day with a sharply worded question: ‘do you feel emboldened, empowered by these diffuse, eclectic historical excursions?’ My answer is ‘not yet, but yes, if we keep working at it’. Watch this space.

June 7, 2015

Links I Liked

First rule for learner drivers: don’t pull out in front of tanks. [h/t Francisco Toro]

Must read. Is that the sound of another tech hype bubble popping? Tom Carothers asks why the tech surge hasn’t had more impact on democracy

‘Why humanitarianism doesn’t get religion…and why it needs to’. Includes excellent discussion of the ‘totem of neutrality’ [h/t Nigel Timmins]

If you ever moderate panels or run meetings, read this advice from Simon Maxwell

World’s deadliest animals (although by only counting homicides, it underplays humans killing each with cars, cigarettes etc) [h/t Conrad Hackett]

World’s deadliest animals (although by only counting homicides, it underplays humans killing each with cars, cigarettes etc) [h/t Conrad Hackett]

‘Google cars are very polite. I feel safer around a self-driving car than most other California drivers.’ [h/t Chris Blattman]

If you’re interested in gender and/or the informal economy, the new WIEGO blog is essential reading

How to Swear Like a Brit. See also what Brits say v what they mean (FP2P all time most popular post) [h/t Tim Harford]

June 5, 2015

Africa’s renewable future – the coming energy revolution

Apologies for extra post today, but the guest posts and new papers are coming thick and fast. John Magrath, Oxfam researcher and renewable energy fan, celebrates a new report by Kofi Annan.

In Zimbabwe last week I was talking to a nurse at a rural health centre who described how the cost of two candles can be a matter of health or hunger, or even life or death. The health centre had no electricity, so expectant mothers were told to bring two candles with them to provide light for their delivery. Two candles cost a dollar, which is the same cost as going to the mill to get your maize ground into meal for a family’s dinner. Lacking a dollar, mothers-to-be naturally prioritised feeding their children over buying candles, and as a result, often left it too late to reach the health centre and gave birth on the road, at night.

The Oxfam programme in Zimbabwe has been installing solar panels at some health centres and schools, for lighting, pumping water and refrigeration, and has been pioneering a market-based system whereby people buy inexpensive but bright and robust solar lanterns. The results are impressive, including big increases in attendance at the centres and better health all  round. But such programmes are still a drop in the ocean. What Africa needs is an energy revolution, which is where a resounding new call from Kofi Annan comes in.

round. But such programmes are still a drop in the ocean. What Africa needs is an energy revolution, which is where a resounding new call from Kofi Annan comes in.

His Africa Progress Panel released its new report Power, People, Planet: Seizing Africa’s Energy and Climate Opportunities today. It is a stirring document (and well written as one would, since its lead author is ODI’s Kevin Watkins). In his introduction Annan rightly connects the climate crisis with the energy crisis. While temperatures rise, energy access for millions of people in Africa remain negligible. Thus far, he says, we have lacked the political leadership and practical policies needed to break the link between energy and emissions. But things are changing.

According to Annan: ” Africa is well placed to be part of that leadership. Some African countries are already leading the world in low-carbon, climate-resilient development. They are boosting economic growth, expanding opportunity and reducing poverty, particularly through agriculture. African nations do not have to lock into developing high-carbon old technologies; we can expand our power generation and achieve universal access to energy by leapfrogging into new technologies that are transforming energy systems across the world. Africa stands to gain from developing low-carbon energy, and the world stands to gain from Africa avoiding the high-carbon pathway followed by today’s rich world and emerging markets. Unlocking this “win-win” will not be easy. It will require decisive action on the part of Africa’s leaders, not least in reforming inefficient, inequitable and often corrupt utilities that have failed to develop flexible energy systems to provide firms with a reliable power supply  and people with access to electricity…..Their challenge is to embrace a judicious, dynamic energy mix in which renewable sources will gradually replace fossil fuels”.

and people with access to electricity…..Their challenge is to embrace a judicious, dynamic energy mix in which renewable sources will gradually replace fossil fuels”.

The report puts its finger on the problem – governance of power utilities: “Energy policy is at the heart of the opportunity. For too long, Africa’s leaders have been content to oversee highly centralized energy systems designed to benefit the rich and bypass the poor. Power utilities have been centres of political patronage and corruption. The time has come to revamp Africa’s creaking energy infrastructure, while riding the wave of low-carbon innovation that is transforming energy systems around the world”.

Africa, says the report, should aim for a 10-fold increase in power generation by 2040. And it pinpoints how to achieve it: “From an African perspective, renewable technologies have two distinctive advantages: speed and decentralization. They can be deployed far more rapidly than coal-fired power plants and they can operate both on-grid and off-grid”.

Amen to all that, but does the report truly plot a realistic, compelling path that will unlock this difficult win-win? I think there are two problems here. One is that despite its emphasis on renewables, the Panel is compelled to adopt an “all of the above” approach when it comes to meeting Africa’s energy needs. This is politically (and many would say morally) realistic, but, the trouble is that there are trade-offs between still powerful fossil-fuel interests and emerging renewables. And which message will Africa’s leaders pay most attention to?

For simply promoting renewables the report has highly practical suggestions; governments need to promote off-take arrangements, utility purchase arrangements and feed-in tariffs. However, the second problem is that when it comes to the entire energy picture the 182-page report runs a risk of being just too wide-ranging in its recommendations. There is nothing wrong with any of them, but they essentially go far beyond energy alone and could be applied to every sector. They include investing 3-4% of GDP in energy sector development via reforming tax administration to raise the tax to GDP ratio; ending tax evasion and stemming illicit financial flows; scrapping subsidies; regulating utilities; investing in agriculture and finding new models of planned urbanization.

For simply promoting renewables the report has highly practical suggestions; governments need to promote off-take arrangements, utility purchase arrangements and feed-in tariffs. However, the second problem is that when it comes to the entire energy picture the 182-page report runs a risk of being just too wide-ranging in its recommendations. There is nothing wrong with any of them, but they essentially go far beyond energy alone and could be applied to every sector. They include investing 3-4% of GDP in energy sector development via reforming tax administration to raise the tax to GDP ratio; ending tax evasion and stemming illicit financial flows; scrapping subsidies; regulating utilities; investing in agriculture and finding new models of planned urbanization.

If that reads somewhat like a reconfigured version of previous Human Development Reports, the APP report is especially urgent and topical in emphasising that the Paris climate summit in December is a crucial opportunity for the coming together of the climate and energy agendas. It calls for massive emissions cuts, an exit from coal, and carbon budgeting and pricing to mitigate climate change, and for developed countries to step up and deliver climate finance. A particularly interesting suggestion is for a “global connectivity fund” under the auspices of the Sustainable Energy for All partnership, arguing that “the SE4ALL remit includes supporting universal access to energy and increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix, but it lacks a bridge to financing mechanisms”.

Kofi Annan introduces the report (3m)

June 4, 2015

Latest high level broadside on inequality – “In It Together…” from the OECD

Guest post from Oxfam inequality researcher Daria Ukhova

Last month, the OECD published a new flagship report on inequality In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All, continuing a series and building on the findings of the previous reports Growing Unequal? (2008) and Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising (2011). At Oxfam since the launch of our Even It Up campaign, we have been closely monitoring the inequality debate, and OECD’s reports clearly represent important landmarks in its development. So, what have we learnt? And what was missing in the OECD’s new tome?

The report has already received quite a bit of attention in the media, but for those who still have the report sitting unopened in their mailboxes here is a quick summary of the main arguments:

Income inequality is rising across OECD countries, with the richest 10% of the population now earning 9.6 times the income of the poorest 10% (in the 1980s, this ratio stood at 7:1 rising to 8:1 in the 1990s and 9:1 in the 2000s)

Income inequality and poverty increased during the current crisis (post-2008)

Rising inequality holds back economic growth. Between 1990 and 2010, OECD economies lost a whopping 4.7% off cumulative growth.

Poorest 40% are being increasingly left behind by the growing inequality in terms of their incomes, but also their educational attainment, skills and employment

Poorest 40% are being increasingly left behind by the growing inequality in terms of their incomes, but also their educational attainment, skills and employmentRise of non-standard work in the past twenty years is one of the key drivers of growing inequality

Bringing more women into full-time work with higher relative wages has reduced the growth of inequality measured by the gini index by approximately 1 percentage point

Wealth inequality is much higher than income inequality, with the bottom 40% of people across the OECD owning only about 3% of total wealth, compared to the 50% owned by the top 10%

To tackle all the above, OECD suggests a focus on increasing women’s economic participation, promotion of employment and creation of good-quality jobs, investing in human capital through better skills and education policies, and, finally, redistribution through taxes and transfers.

If you get to the very end of the report, you will also find a nice small chapter on emerging economies, which leaves some hope that inequality could actually be tackled through the right combination of fiscal policies, an important part of which comprise publicly funded healthcare and education (Unfortunately, that doesn’t warrant a mention in the executive summary)

While all the above might prompt a mild twinge of déjà vu, there are several important aspects of this report – apart from the  wealth of great new data for which we are always thankful – that I would argue require attention, as potentially crucial for defining the future terms of the debate about inequality.

wealth of great new data for which we are always thankful – that I would argue require attention, as potentially crucial for defining the future terms of the debate about inequality.

Inequality, economic growth, and poverty. In the new report, the OECD has tried to establish the links between these three phenomena, which so far have been mostly explored in pairs, as the relationship between inequality and growth and the relationship between inequality and poverty. While confirming previous arguments about the negative impact of inequality on growth and on poverty, the OECD has gone a step further, arguing that the mechanism through which inequality actually undermines growth is through the channel of human capital. Specifically, they find that higher levels of inequality result in worse educational attainment, skills and employment among the poorest 40%, which then translates into lower levels of human capital and lower growth. The report, however, does not explore the underlying causes of this relation. Comparing the low and high income inequality countries in terms of degrees of their educational systems’ privatization or labour market flexibilisation could shed light on the questions re why poor people in more unequal countries ‘invest’ less in their human capital.

Horizontal and vertical economic inequality. By dedicating a whole chapter to looking at how the changes in women’s economic activity in recent decades have affected the dynamic of economic inequality among households, the OECD has done a great job of mainstreaming a debate that until recently was primarily heard only at feminist economics conferences. Looking at how other types of horizontal inequality (ethnic, racial, etc.) affect current trends of vertical economic inequality could become another important step in making mainstream economic debates less gender- and colour-blind.

Precarisation of work and inequality. Although the OECD prefers to refer to this phenomenon as a rise of non-standard work or NSW (under which they include temporary contracts, part-time employment and self-employment), by making an argument about NSW being a primary driver of the recent growth of inequality, the OECD seems to be actually moving away to some extent from its earlier position on the need to flexibilise labour markets. The issue that remains unaddressed by the report is why have the labour markets become so flexibilised in the first place? Addressing this question would probably require a degree of reflexivity by the OECD that the format of such report, unfortunately, does not allow.

40% vs. 1%: As the authors of the report argue: ‘Much of the recent debate surrounding inequality has focused on top earners, especially the “top 1%”. Less well understood is the relative decline of low earners and low-income households – not just the bottom 10% but the lowest 40%. (…) Just as with the rise of the 1%, the decline of the 40% raises social and political questions. When such a large group in the population gains so little from economic growth, the social fabric frays and trust in institutions is weakened.’ Although the report does have a chapter on increasing wealth concentration and even has some recommendations on taxing the rich (with the purpose of raising more revenue for social protection), it does, indeed, strongly focus on the dynamic at the bottom of distribution. It even goes as far as to show – through a quite complex statistical model – that changes at the top of redistribution have actually had no impact on current inequality increases. As a result, the report fails to explore how the processes at the top and at the bottom of distribution are related – when someone is losing, isn’t it that someone else is gaining? In the end, aren’t we “in it together”?

40% vs. 1%: As the authors of the report argue: ‘Much of the recent debate surrounding inequality has focused on top earners, especially the “top 1%”. Less well understood is the relative decline of low earners and low-income households – not just the bottom 10% but the lowest 40%. (…) Just as with the rise of the 1%, the decline of the 40% raises social and political questions. When such a large group in the population gains so little from economic growth, the social fabric frays and trust in institutions is weakened.’ Although the report does have a chapter on increasing wealth concentration and even has some recommendations on taxing the rich (with the purpose of raising more revenue for social protection), it does, indeed, strongly focus on the dynamic at the bottom of distribution. It even goes as far as to show – through a quite complex statistical model – that changes at the top of redistribution have actually had no impact on current inequality increases. As a result, the report fails to explore how the processes at the top and at the bottom of distribution are related – when someone is losing, isn’t it that someone else is gaining? In the end, aren’t we “in it together”?

And here’s a quick video summary of the report:

June 3, 2015

Why 17 goals and 169 targets are not enough – your chance to vote

Time for a little (non-Oxfam) contrarianism, and a new poll (see right). In September, the UN will agree the new framework for global development for the 15 years to 2030. This week the 43 page ‘zero draft of the outcome document‘ was published and

Why are you confused; it’s perfectly complex…..

the interwebs will rapidly fill with aid wonks and politicians scoffing at the ‘christmas tree’ of goals and targets (17 of the former, breaking down into 169 of the latter). Earlier drafts were ‘overwrought and obese’ says CGD’s Charles Kenny, who thinks we have ‘lost the plot’. How on earth can we prioritise 17 goals?

But then I got to thinking about Charles’ CGD colleague Owen Barder, and his excellent recent post on complexity and development. If development is indeed the outcome of a complex adaptive system, as Owen argues, what does that imply for the discussion on goals and targets?

Because goals and targets belong squarely in the linear, planners’ camp; they fit with the kind of system epitomised by Stalin but, according to Bill Easterly, still dear to the heart of many aid agencies. We have goals and targets, a budget, we devise big linear plans (logframes etc), roll them out, monitor, evaluate and voila – development!

But an increasing number of aid wonks (including Owen) think this is deeply mistaken – both morally and practically. Development doesn’t work like this; it’s messy, unpredictable, context specific. What works in one place doesn’t work in another. Rather than grand plans, we need to ‘cross the river by feeling the stones’.

And who is this ‘we’ anyway? The MDGs should really have been called the MAGs – the Millennium Aid Goals, because as Charles recognizes, there is far more evidence that they influenced the quantity and quality of aid than that they directly affected development, or developing country government policy. But we know that even if aid volumes hold up (a big if) it is falling fast as a percentage of government revenues in poor countries. So disciplining aid through global goals and targets will deliver diminishing returns.

In a complex adaptive system, where governments are in the driving seat, what kinds of structure make sense for the post 2015 system? I think there is at least a case for saying, the more goals and targets the better:

King John signs Medieval Development Goals

That means they are more likely to be relevant to national context: national politicians, civil society organizations, public intellectuals etc will latch onto those goals that are most useful and make a big fuss about them, ignoring the rest. Sounds good to me, and a lot more democratic than some externally imposed shopping list.

They can evolve with time: Magna Carta is getting bigged up this year on its 800th anniversary, but understandably, some of its clauses (‘No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land’) have withstood the time more than others (all that stuff about fish weirs in the Thames). A greater variety of goals and targets will ensure that some remain relevant over the full 15 year period and beyond.

One of the many weirdnesses of the post-2015 discussion is how little it references other international instruments, many of

which have had considerable influence over national decision-making, for example by being enshrined in national law (honourable exception here). Look at some of the better known, like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Both have 30 articles (is that some kind of rule in UN conventions?), lots of goals and no targets (tsk tsk, say the Planners). And I would argue they have worked pretty well.

I have long tried to avoid talking about the SDGs, because so much of the discussion struck me as deeply futile (here’s a 2012 paper explaining why I wasn’t going to be working on the SDGs. Oh, wait.). But in many ways, now the Christmas tree phase is ending, we are getting to the interesting bit – what will determine whether the new arrangement makes any difference on the ground? Issues such as how the SDGs are monitored and reported are going to be crucial – will there be regional league tables every year that name and shame the laggards compared to their neighbours, and provide a hook for activism, or just some bland five yearly number crunching in New York? If you care about politics, development and reality, now is the time to pay attention.

I sent this over to Owen and here’s his reply:

‘I’m torn between thinking that complexity implies many targets (your point) and thinking it implies just one or two big hairy

ones, to which there are many possible paths. Something in between seems to be the worst of all worlds.

I guess it depends what you think the goals and targets actually do. I suspect there is some international norming, which is useful; and some establishment of a common language, which is also useful. So they are useful for “framing” rather than changing incentives or behaviour directly. This can be important in defining the space within which the complex adaptation occurs

If you are trying to “frame” then you need something that people can get their arms around. I’m not sure how you do that with 17 goals and 169 targets. So I’m more inclined to think that complexity suggests a small number of big targets rather than many targets.’

As it’s been ages since you voted on anything, here’s a very geeky poll on Owen’s comment and this post:

Q: If development is indeed a property of a complex adaptive system, are 17 goals and 169 targets

a) too few?

b) too many?

c) about right?

Cast your vote over there on the right

And here’s my 2012 rant on the topic

June 2, 2015

How looking through a doughnut can test if South Africa is on track for inclusive and sustainable development

Oxfam researcher Katherine Trebeck introduces some new work on doughnut economics, (whose inventor, Kate Raworth  has left Oxfam to write a book on it)

has left Oxfam to write a book on it)

There is an African proverb that says:

‘If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together’

It could be taken as call for inclusivity, solidarity, and equality of people and communities. But it might also be read as a mantra for development that takes account of a broader set of priorities – both social and environmental, together.

So far, so sustainable development…?

Maybe, but I can’t help feeling that the ‘agenda’ of sustainable development seems to have lost a lot of vitality (in part through over-use and in part through use by folk who don’t really mean it). In many interpretations it still prioritises the economy as a goal in itself, rather than a means to the end of social justice within planetary boundaries.

So, in this year of all years, giving sustainable development a sugar boost seems timely. Fortunately, there’s something called the doughnut that has the potential to deliver a decent calorific hit.

It started in 2012 when Oxfam released a discussion paper that connected the concepts of social justice and environmental limits in a simple diagram that has become known as the ‘doughnut’. Its author, Kate Raworth, used the doughnut to show the importance of an economy that lifts all people above a social floor (the inner layer) while respecting planetary boundaries (the outer layer of the doughnut).

While the doughnut is fairly familiar SD territory, it doesn’t need to be conceptually different to be powerful. Instead, its value comes from:

its simplicity – one graphic providing an overview of sustainable development, above the complexity

its vision as a compass for successful development

its reframing of how we judge the success of economic ‘progress’

its convening power and creation of space for discussing ideas

From global to national

But proverbs and diagrams (even powerful ones) only get us so far.

Taking the concept to a national level and putting some numbers to it can reveal if the economy is delivering for people and planet and on what aspects economies fall beneath the floor or break through the ceiling.

The challenge is that mapping the extent to which economies operate within the doughnut involves a complex assessment of a range of social and environmental dimensions and Oxfam has recently published reports for the United Kingdom, Scotland, and Wales, that attempt to do this. Next up is South Africa.

This week Oxfam has released a report for South Africa that asks, ‘Is South Africa Operating in a Safe and Just Space?’

For the environmental ceiling the first nine Planetary Boundaries domains developed by Rockström et al were a starting point. We adapted these where necessary, depending on whether they reflected the key environmental concerns in South Africa. We also tested the social floors posited in the 2012 doughnut paper for national relevance, against four criteria such as ‘Is this relevant at the national scale?’ and ‘Are there sufficient reliable data for South Africa that are measured on a regular basis?’, and then through interviews with experts in South Africa.

What did we find? South Africa has crossed its safe environmental boundaries for climate change, freshwater use, biodiversity loss and marine harvesting and is within 10% of crossing the boundaries for arable land use, phosphorous loading and air pollution. The general story is one of an increase in environmental stress since 1990.

On the social floor front, the report reveals that South Africa has not achieved its social floor in any of the 12 dimensions used. For example, almost a quarter of households lack access to electricity; 36% of adults of working age are unemployed; 17% of the population lack a ventilated pit latrine (or toilet); and almost a quarter of households experience hunger. In ten of the twelve, however, these results constitute an improvement in recent years, suggesting that the country is moving in the right direction for these aspects of the social floor.

On the social floor front, the report reveals that South Africa has not achieved its social floor in any of the 12 dimensions used. For example, almost a quarter of households lack access to electricity; 36% of adults of working age are unemployed; 17% of the population lack a ventilated pit latrine (or toilet); and almost a quarter of households experience hunger. In ten of the twelve, however, these results constitute an improvement in recent years, suggesting that the country is moving in the right direction for these aspects of the social floor.

Two dimensions of the social floor are moving in the wrong direction: safety and the proportion of the population living below the national poverty line. Such dimensions of the social floor interact with each other, affecting people’s sense of security, trust, and, ultimately life chances. Similar interactions between the social and environmental sides of the doughnut are not hard to imagine: for example, a collapse in fish stocks due to excessive marine harvesting would result in thousands of job losses. A changing climate is already impacting on farmers, and flooding can halt mining operations and disrupt transport.

Mapping the doughnut for respective countries doesn’t do the hard work for you in terms of specifying policy change. It is a useful visual tool to keep both aspects of sustainable development in the crosshairs. And it is a simple way to start a conversation about a different economy, beyond simply GDP growth.

So it may not, on its own, be a game changer (is anything?).

But it can be used to prompt a discussion about what changing the game would entail (for example, in Scotland it’s helping to frame civil society discussions about how the economy operates, and for whom). And that’s where taking it to the national level, where a lot of policy is made, implemented, tested, and assessed, can kick off some exciting, and potentially game changing, conversations about growth and the purpose of the economy.

June 1, 2015

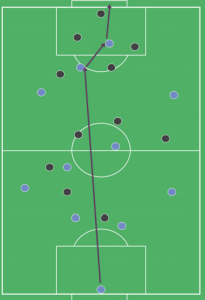

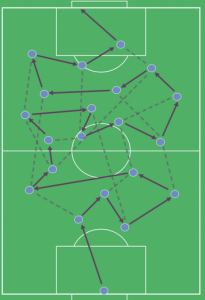

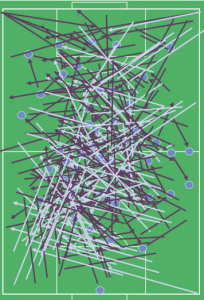

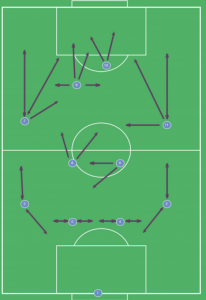

What can soccer tactics tell us about the limitations of planning and logframes?

Universal outrage over Fifagate reflects the fact that football/soccer is fast becoming a universal institution (at least for the

Logframes as Route One

male half of the universe), creating some useful common reference points. As an example, check out this use of soccer tactics to explain the limitations of the logistical framework tools that we increasingly depend on (logframes to insiders), from an organization with the rather baffling name of Global Partners Governance. (American readers please note, for us Brits, soccer = football)

‘The logic of football offers one way to understand the limitations of the logframe. Logframe linearity assumes a ‘route-one’ style of play, or at least something similar to it, where the ball is kicked forward and forward again, and then inevitably into the net (the goal). While this style of play has been favoured by some teams (most notably, and to its detriment, the English national side), it is generally not how teams score.

Forward, sideways, backwards and forward again

In reality a football will go in many different directions before it ends up in the goal – if indeed it does. The ball will be passed sideways, backwards and forwards. Players will be tackled, possibly fouled, driven off their original direction and lose the ball. The ball will be kicked out of play and the flow of the game will be constantly disrupted by one intervention or another

This is much closer to how a governance project will work in practice. Any project is likely to have numerous stakeholders with a direct interest in supporting or preventing progress. As opponents start to disrupt progress, so the supporters need to change tactics and style of play, perhaps making the occasional substitution to counter the effects of the opposition. The interplay of all those actors, and the different resources and skills they have at their disposal means that progress is much more likely to resemble the passage of play in a football match rather than anything that appears in a logframe.

In football, as in politics, there will also be a huge amount of activity during a match

Trying to capture everything

that does not directly affect the progress towards a specific goal. Working out what activity is relevant will emerge only as the game progresses. At the start, it is impossible to identify how each of the 22 players will behave during ninety minutes. And yet, the current application of logframes means that we are essentially being asked to predict the entire passage of the match – and the actions of both supporters and opponents .

Worse than this, that guesswork is then used to create the indicators of success. Projects are measured against an ability to predict, reasonably precisely, how a goal will be scored before the match has started. Without taking into account the opposing side, the conditions or the fitness of your players.The bigger danger is then one of simply following a preset plan, regardless. If you know you’re going to be measured against the activities you said you were going to do then you will do your damnedest to make sure you stick to them, ignoring whether they are actually working or not. In short it makes process more important than outcomes: “Well, we didn’t score but, rest assured, we did exactly what we said we were going to do.”

Logframes as gameplans

It is far better to think of a logframe as a game plan. It is based on an analysis of both your team’s strengths, and that of the opposition. It seeks to understand the tactics that they might use, and counter them, as far as is possible, by playing to your strengths. At the simplest level this would mean deciding what formation to play (1 – 2 – 3 – 4; 2 – 3 – 5; 3 – 3 – 4 or something else entirely), which player is responsible for what, and accepting that you might change that formation at some point during the game.

It is far better to think of a logframe as a game plan. It is based on an analysis of both your team’s strengths, and that of the opposition. It seeks to understand the tactics that they might use, and counter them, as far as is possible, by playing to your strengths. At the simplest level this would mean deciding what formation to play (1 – 2 – 3 – 4; 2 – 3 – 5; 3 – 3 – 4 or something else entirely), which player is responsible for what, and accepting that you might change that formation at some point during the game.

The logframe should, in short, set out the project logic and the theory of change. These are strategic considerations. The tactics, namely, when to move from defence to attack and which players you pick (like the choice of activities) are tactical considerations that will need to change as circumstances dictate.’

The paper then departs from football and becomes much less convincing (or interesting) on how to deliver more effective projects.

The offside rule is also a handy intro to institutions by the way, and Rakesh Rajani has a whole shtick about soccer and development. Anyone fancy pulling this together into a manual?

May 31, 2015

Links I Liked

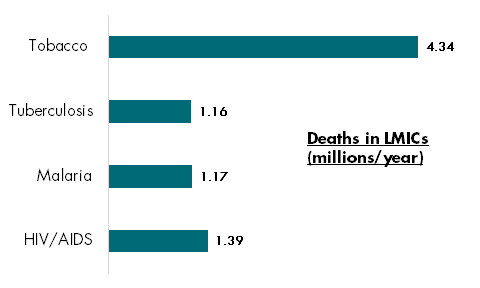

Tobacco-related diseases kill 4.3 million people each year in low- and middle-income countries. That’s more than HIV/AIDS,  malaria, and tuberculosis combined (see figure). So could someone please explain why it isn’t a ‘mainstream development issue’?

malaria, and tuberculosis combined (see figure). So could someone please explain why it isn’t a ‘mainstream development issue’?

Chocolate is good for you: The Chance Result the Whole World Yearned to Believe [h/t Richard King]

What did Otpor (Serbian protest movement) get right, that Occupy got wrong? Analysis by Harvard Business Review [h/t Rakesh Rajani]

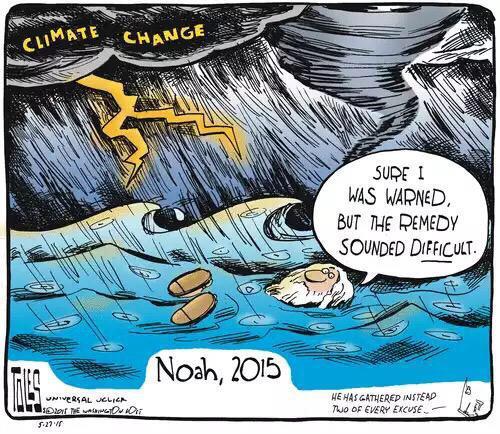

Think we’ll be seeing more of this cartoon in the run up to the Paris climate change summit in December.

Think we’ll be seeing more of this cartoon in the run up to the Paris climate change summit in December.

The ‘us’ & ‘them’ in trade agreements (e.g. the TPP) is not nation v nation, but investors (one dollar/one vote) v voters (one person/one vote)

72 countries have more than halved the proportion of undernourished people. Global total down to 795 million. The FAO’s new State of Food Insecurity report

There was quite a lot about football on twitter last week, for some reason (John Oliver provides essential background):

“Football has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.” George

Orwell quoted by Matt Andrews, who argues that football income is a bit like natural resources – money out of the ground, with a high likelihood of corruption.

‘A clean FIFA will get rid of African/Asian influence and ignore ¾ of the poor world.’ Branko Milanovic worries that a

cleaned-up soccer will end up looking like tennis.

And it’s not just about corruption: in Qatar, “As things stand, more than 62 workers will die for each game played during the 2022 tournament.”

And finally, I rather liked this WaterAid spoof for last Thursday’s World Menstrual Hygiene Day, but still prefer the ad below - wonder if Richard now regrets his Facebook post? It was one of 8 chosen by the Guardian in advance of the Cannes ‘glass lion awards’ later this month. Interesting to see just how good private sector is at targeting attitudes and beliefs – maybe we should leave that bit to them, and they should give up on the service delivery?…..

May 28, 2015

How is the Syria situation changing on the ground, after 4 years of fighting?

Went to a fascinating briefing on Oxfam’s work in the Syria crisis last week, which set out the underlying trends and the  evolving challenges for aid agencies, beyond the periodic TV news bang bang coverage..

evolving challenges for aid agencies, beyond the periodic TV news bang bang coverage..

The numbers are stark:

Total of 18 million people in need of humanitarian assistance inside and outside Syria – including almost 4m registered refugees and about 1.8m unregistered

12.2 million people inside Syria needing humanitarian assistance, including 7.6 million Internally Displaced People (IDPs) and more than 5.6 million children.

11.6 million people in urgent need of access to clean water and sanitation.

Death toll estimate of 220,000 and counting…

The initial response to the outbreak of fighting was short term, both from the Syrians who fled (who expected to be back home in a few months, so started selling assets etc expecting to be able to recoup their losses), and the aid agencies, who saw this as a short term response.

Four years in, no-one thinks that any more. Aid agencies need to think through responses if refugees are staying for decades rather than months. Some of the challenges include:

- waning public interest in the rich countries, meaning that new aid appeals are seriously underfunded. The World Food Programme has faced repeated challenges in meeting the costs of their monthly rations to refugees and has had to make cuts in recent months

- growing hostility in some communities in host countries due to the economic burden (roughly 1.5m refugees in Lebanon – population 4m), exacerbated by security concerns over ISIS and other forces. The incredibly generous initial welcome and solidarity to refugees from Syria from neighbouring countries has given way in some areas to suspicion, resentment and raids by security forces. After taking a number of refugees that European nations would never even have countenanced, regional Governments are also echoing the nasty ‘pull factor’ rhetoric of the Europeans – helping refugees will just encourage more to follow.

Oxfam has mounted a big and complex response in Syria, working from government held areas but with some projects that reach across front lines: Over half of the pre-conflict water infrastructure has been damaged and we have been repairing water systems, alongside emergency measures like trucking water and providing hygiene kits to displaced people. That entails close collaboration with the Syrian authorities.

Oxfam has mounted a big and complex response in Syria, working from government held areas but with some projects that reach across front lines: Over half of the pre-conflict water infrastructure has been damaged and we have been repairing water systems, alongside emergency measures like trucking water and providing hygiene kits to displaced people. That entails close collaboration with the Syrian authorities.

We are also doing international advocacy on the conflict, and running large refugee and host community programmes on water, protection and more, in Lebanon and Jordan, including links to the Palestinian refugees who have been there for 50 years (shape of things to come?).

Everything is difficult: in Syria, security of staff, government delays, restricted access to the people we’re trying to help; outside Syria, governments and populations’ increasing disenchantment.

Our global campaigning has evolved from an initial focus on aid to long-term solutions – how are refugees supposed to earn a living when host countries restrict the areas in which they can work? Can potential host countries improve on their lamentably low offers of resettlement? Will the UN Security Council ever act on arms flows and other issues?

But this is also uphill work – our campaigners are good at getting public attention and making the case for aid, but influencing regional governments or the UNSC is a much harder proposition. Interestingly (and unexpectedly), our global aid campaigns have sometimes helped –the Jordanian authorities were really pleased with our work on ‘fair shares’, showing what different countries should be contributing to the relief effort, based on their economic weight.

The team reckon one element of a 10-20 year advocacy strategy is beefing up the quantity and quality of research (music to  my ears). The fair shares papers are a good start – officials from at least three governments have told us they have helped to prise more cash out of their finance ministries.

my ears). The fair shares papers are a good start – officials from at least three governments have told us they have helped to prise more cash out of their finance ministries.

We will also have to shift to focus much more on livelihoods (how are refugees in neighbouring countries going to earn a living for the next X years?). That shows the importance of getting beyond our self-imposed disciplinary siloes of ‘humanitarian’ v ‘long-term development’. For one thing, refugees are likely to depend heavily on the informal economy (especially when other options are closed off). Elsewhere in Oxfam we have good work on the care economy (crucial in allowing women in particular to work in informal jobs), and great partners such as WIEGO – need to join up.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers