Duncan Green's Blog, page 162

June 22, 2015

The SDGs are just getting interesting – what needs to happen next to make them have impact?

I spent a day in Madrid last week talking to Spanish aid wonks (it was cold and wet, in case you’re feeling jealous). One of the

Got to catch them all…..

main topics of conversation was the post 2015 process, and it convinced me that I need to move on a bit from my previous rejection of the whole process as a waste of breath. We are where we are – there has been a huge investment from (some) political leaders, and (a lot of) global civil society in a big conversation about the ‘world we want’. What happens next?

As Claire Melamed has argued, that is a positive in itself. OK, but what determines whether that big conversation leaves a legacy, and in ten years time is affecting how decision makers behave? The MDGs’ main impact was on the quantity and quality of aid, but aid is of declining importance in all but a shrinking pool of aid-dependent economies. What else have the SDGs got in the locker?

One way that the SDGs could remain relevant is by influencing global norms along, say, the lines of CEDAW, but I don’t think they are designed to achieve that – unlike UN Conventions, the SDGs have no process of ratification, followed by incorporation into national law.

Which leaves something more intangible – can the SDGs gain traction over the decisions and priorities of national governments, South and North? As a way of boiling all this down, maybe the research question should be – how could the SDGs help an official in Bihar who wants to tackle open defecation to get greater support for her work?

Some of the Spanish wonks wanted to meet the challenge head on – if Spain signs up to the SDGs, then campaigners should ask the government to set explicit targets and timetables for reducing inequality and a hundred other good things that are in the draft. Ain’t gonna happen – not in Spain, where government negotiators see the SDG negotiations as about ‘them’ not ‘us’, but non aid-dependent governments in developing countries are equally unlikely to sign up – why should they?

The alternative is a more softly softly approach, designing the process of monitoring and reporting to generate steadily increasing pressure on governments to go further than they would otherwise have done.

It’s all about traction…..

In 2012 my very crude answer on this was ‘league tables’ – pit India against Bangladesh and let civil society and media use local rivalry and shame to push for action. But how else can the SDGs be ‘converted into public policy’, as one speaker in Madrid put it? Factors could include:

Picking the right indicators: ones that can be collected and updated regularly, that mean something to normal people, which measure important stuff. (I’m not sure ‘yay, the Gini has fallen by 0.4% since last year’ passes either of the first two tests, by the way). Perhaps use perception indicators like those on corruption used by Transparency International – ‘does your government work in the interests of poor people?’ But the data geeks are all over the indicator discussion like a rash, so let’s move on.

How will governments be required to report on their performance against the SDGs? How regularly? To whom? Will other bodies (parliamentarians, civil society organizations, think tanks) be allowed to submit alternative reports? Will there be a real debate around the reports?

How will the post 2015 system (presumably the UN) report on progress – a diffuse global conference in New York every couple of years, or a nowhere-to-hide comparison of SDG heroes and zeroes that gets politicians’ attention (yes, including league tables)?

As for who could use such mechanisms, it is of course far wider than CSOs. Off the top of my head:

Strengthening the hand of internal champions within states

Parliamentarians

International Bodies (UN, Bretton Woods, bilateral, regional organizations)

International Markets (imagine if ratings agencies started marking countries down as greater credit risks for not tackling inequality!)

Faith leaders

Enlightened fractions of the private sector

Subnational governments – both as targets and pushing for action (eg, our state has the worst SDG stats in India – what are you going to do about it, Delhi?)

Other opinion shapers: academics, media, judiciary

Shifting public narratives – the power of good and bad examples to affect how people see the role of government, for example

Shaping the views of future leaders – eg via universities.

Everyone always likes a research agenda, so as well as asking governments what actually influences their decisions, how about

and leverage of course

consulting these groups about what kind of mechanisms might make the SDGs relevant to them?

One option for an implementation mechanism might be that used by the Open Governance Partnership. When countries join the OGP, they commit to broad principles outlined in the Open Government Declaration. Once signed up to this overarching vision, countries develop their own two-year action plan with concrete open government reform commitments. That would domesticate the SDGs into something nationally owned and relevant, providing the basis for annual reporting and debate, which over time could shift norms, policies and practices faster than they would otherwise have done. That seems like a pretty desirable outcome and according to our lead SDGs wonk, Takumo Yamada, something along these lines is already happening in several countries (he mentioned Ghana, Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia and Denmark).

So don’t give up on the SDGs – they’re just getting interesting.

Update: This, from an excellent AidData post on the findings of their survey of developing country policy makers (which I reviewed last month – should have linked to it in this post, but forgot!)

‘The findings from the 2014 Reform Efforts Survey should give pause to those who are negotiating the soon-to-be-established Sustainable Development Goals. While a great deal of effort is currently being devoted to the identification of technically appropriate and politically feasible indicators and targets, UN negotiators would be wise to think long and hard about how the modalities of performance assessment that they choose may influence the incentives and behaviors of the governments they are monitoring and evaluating. The international community would serve itself well by listening carefully to the makers and shapers of policy in low- and middle-income countries.’

June 21, 2015

Links I Liked

All male panels, the India version. Some good advice to organizers here on handling language, questions, roles etc

What’s the origin of the ICC’s Africa problem (since 2002, all 36 warrants have been for Africans)?

‘All you need is a big heart and access to the internet’. Great takedown of the DWSC (digital white saviour complex)

Faces of the Somali Remittance Crisis [h/t Michael Clemens]

Last year, the world spent $14.3tn (13.4% of global GDP) on costs related to violence. New report from Global Peace Index.

William Hague’s summit against warzone rape seen as ‘costly failure’, costing five times more than the UK government spent on actually tackling rape in war zones

Is the human rights movement ‘all about “bourgeoisie talk.”? Tunisian activist Amira Yahyaoui makes case for a more grassroots human rights movement

What happens when communities in New York organize? The who/when/how of dozens of wins [h/t Rakesh Rajani]

Unmissable. The escalating and hilarious video war between dodgy ex-FIFA boss Jack Warner and ‘comedian fool’ John Oliver

June 18, 2015

Is the IMF Dismantling Trickle Down Economics?

Oxfam America researcher and inequality guru Nick Galasso hails a new report that finds the poor and middle classes are  the main engines of growth – not the rich

the main engines of growth – not the rich

In a new report, the IMF effectively drives the final nail into the coffin of trickle-down economics. The top finding, in their words, is that “if the income share of the top 20 percent (the rich) increases, then GDP growth actually declines over the medium term, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle down.”

In contrast, an income bump to the poorest 20 percent is associated with higher GDP growth. The report concludes, “The poor and the middle class matter the most for growth.”

These findings build on previous work from the IMF demonstrating that high inequality negatively affects growth. While the previous work suggested overall inequality is bad for growth, the current paper contributes by dissecting the income distribution to show what happens to growth when the poor do better compared to the rich.

What does this mean for policymakers?

The big take-away from this research is that sound macroeconomics prioritizes gains to poor and middle income groups. This is significantly different to what many advanced and emerging country governments have pursued in recent decades. Instead of policy strategies aimed at increasing low and middle incomes, they have pursued agendas that enhanced and reflected the economic interests of the wealthiest.

I’M For Redistribution….

Trickle down had two things going for it. First, for many years the theory enjoyed support from economists and experts. Therefore, it had some semblance of legitimacy. Hopefully, this report puts an end to that. Second, since it implicitly benefits the wealthiest, it wields significant political and ideational power. This second point likely explains its longevity.

As a result, the last few decades have witnessed governments removing important economic regulations, steadily decreasing taxes on the wealthiest, privatizing services like water and health, and weakening workers’ wages and power to organize.

It’s no wonder that 7 out of 10 people in the world live in countries where inequality has increased since the late 1980s. These policies ensured that low and middle income groups grew much slower than the richest 10 percent across countries.

What are the keys to poor and middle income growth?

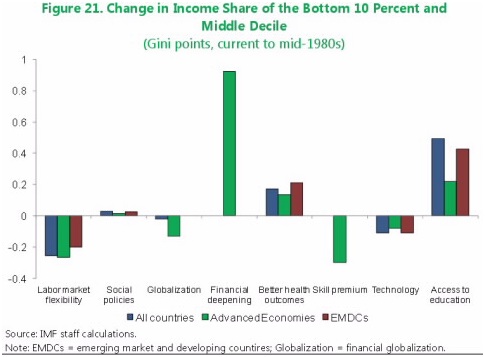

If growing the incomes of the poor and middle classes is key to shared prosperity and growth, what should governments be doing? According to the authors, the answers are not surprising. In countries at all levels of development, better access to education, redistributive social policies, and better healthcare are associated with higher incomes accruing to low and middle income groups.

Access to credit (“financial deepening”) seems to be an important, and often overlooked, inequality reducer. In advanced economies, more accessible credit has played an important role in reducing inequality. Conversely, lack of access has boosted inequality in emerging economies, where credit is largely limited to the wealthy and the biggest private sector firms.

According to the report, closing the gap in access to education has been one of the most important inequality reducers. However, the report notes that while there’s been overall improvement, access is still skewed toward privileged groups.

These findings, and the impact they have on inequality levels, are shown in the chart below.

What does the report miss?

The report is heavy on good-sounding policy recommendations that governments should take up. For instance, the authors point to the ways in which fiscal policy can be a sharp tool for reducing inequality; governments must curb the tax breaks and handouts given to the rich.

Yet, for me, the influence the wealthy exercise over government policy-making represents the biggest barrier to reducing inequality. In too many countries, our political systems resemble oligarchies instead of democracies. Across the world, collusion among economic and political elites drives pro-rich policies at the expense of greater shared prosperity.

Alas, the world’s economic inequality problem has little to do with economics. Rather, it’s a symptom of entrenched political inequality that underpins the drivers of inequality identified by the IMF: rising labor market flexibility, unequal access to credit, healthcare and education.

This isn’t conspiracy theory, either. Recent research from leading American political scientists show there’s a total disconnect between the preferences of average Americans and how Congress votes. Conversely, Congress overwhelmingly votes in favor of the preferences held by the richest Americans.

This is a great report from the IMF. It’s always helpful when large financial institutions generate solid evidence about the many scourges of extreme inequality. However, real progress may remain elusive until we can address the massive power inequities between the super wealthy and the rest of us.

The IMF has set off the alarm for governments to wake up and start actively closing the inequality gap, not just between the rich and poor, but for the middle class too. The paper’s message is pretty clear: If you want growth, you need to invest in the poor, invest in essential services and promote redistributive tax policies.

June 17, 2015

Crunch time for global humanitarianism – funding can’t keep up with need, so what else is needed?

Ed Cairns, Oxfam’s senior policy adviser on humanitarian advocacy, reviews the latest overview of global humanitarian aid.

[Update: in response to readers' comments, I've stuck up a very retrogressive humanitarian v long term aid poll to the right - please hold your nose and vote]

This year’s Global Humanitarian Assistance report highlights some startling figures. For years these reports from the Development Initiatives stable have been the go-to guides on the numbers around humanitarian funding. But recording the sometimes small changes from year to year hasn’t always grabbed headlines. Private contributions to humanitarian aid, for instance, increased from $5.4 billion in 2013 to $5.8 billion in 2014.

But the new 2015 report comes up with some more striking numbers. 93% of people in extreme poverty (below $1.25 a day) live in countries that are either politically fragile or environmentally vulnerable, or both. That is a startling reminder of, as the authors say, ‘the need to address poverty, vulnerability, risk and crisis together’ – or to put it another way, to tackle the causes as well as the consequences of humanitarian crises.

Which makes it all the more tragic that the world spent more money on humanitarian aid in 2014 than ever before – up 19% to $24.5 billion– while doing a pretty terrible job of stemming the rising tide of disasters and conflicts. OK on cure; massive fail on prevention.

Which makes it all the more tragic that the world spent more money on humanitarian aid in 2014 than ever before – up 19% to $24.5 billion– while doing a pretty terrible job of stemming the rising tide of disasters and conflicts. OK on cure; massive fail on prevention.

A few weeks ago, a large group of NGOs condemned governments around the world for Failing Syria. But it’s worse than that really. What crisis or failed state has international diplomacy successfully resolved recently? South Sudan? Yemen? Ukraine? I don’t think so.

And Vanuatu’s President had a good point when he said that climate change had contributed to the death and destruction that Cyclone Pam wrought on his Pacific island nation in March.

In the face of that, record humanitarian aid is obviously needed; and some readers will look at the Global Humanitarian Assistance report and mildly rejoice. In the age of austerity, it is pretty amazing that the world’s humanitarian spending increased by a fifth in 2014. The OECD countries that still give the vast majority of government donations – $16.8 of the $18.7 billion – gave $2.5 billion more in 2014 than the previous year. But governments in the Gulf more than doubled their funding to reach $1.7 billion; and Turkey was the 3rd most generous government in the world if you count the $1.6 billion it spent on hosting Syrian refugees in 2013. Only the US and the UK gave more humanitarian aid.

But this new report has far less comforting figures too; 2014 was a record year also for the $7.5 billion that was not given to  address the highest level of unmet needs ever recorded in UN appeals. No-one pretends that UN appeals are incredibly reliable measurements of human need; but such shortfalls in funding can still have devastating consequences. At the end of last year, the World Food Programme had to suspend food aid to 1.7m Syrian refugees when it ran out of money, and was only able to reinstate its assistance after it raised millions of dollars through social media.

address the highest level of unmet needs ever recorded in UN appeals. No-one pretends that UN appeals are incredibly reliable measurements of human need; but such shortfalls in funding can still have devastating consequences. At the end of last year, the World Food Programme had to suspend food aid to 1.7m Syrian refugees when it ran out of money, and was only able to reinstate its assistance after it raised millions of dollars through social media.

It was always thus, some might say, and the annual Global Humanitarian Assistance reports have always told the story of the gap between what is needed and paid for – or perhaps more fairly, how rising aid has been outpaced by increasing need. And this year’s report tells that story pretty bluntly with this final stat: 107.3 million people were affected by disasters caused by natural hazards in 2014, which is an increase of 10.7 million people in only one year. (Watch out for the latest figures of those fleeing conflict – from UNHCR to mark World Refugee Day this Saturday.)

The unprecedented ‘hole’ in humanitarian financing that this new report reveals should be an impetus to find new and more effective ways to fund humanitarian action, and the UN Secretary-General has a High Level Panel exploring those, to report in November. But it should also be an impetus to do more to address the causes as well as the consequences of humanitarian crises – which is a subject I’ll come back to when Oxfam publishes its paper for next year’s World Humanitarian Summit in a few weeks time.

And here’s the mind-blowing exec sum infographic. Really hope you’re not trying to read this on your phone ……

Update: Makarand and Paul have gone head to head in the comments section on whether a bigger slice of aid should go to humanitarian response. So I thought I’d invite other readers to vote. Here’s the question:

Humanitarian aid currently accounts for 13% of total official aid from traditional (DAC) donors. In your view should it

a) increase to a greater % of overall aid

b) stay at about that level

c) be a smaller % of overall aid

d) I would like to take the wimpy way out and say that overall aid levels should increase, including both humanitarian and other forms

and yes, you can vote for more than one (but no more than 2 – that wd be weird).

(Caveat: For those like Makarand who want to overcome the unhelpful polarization of humanitarian v development aid, let’s assume that both humanitarian AND development aid should do more to reduce the risk of future disasters.)

June 16, 2015

How can big aid organizations become Fit for the Future? Summary of my new paper

My navel-gazing paper on the future of INGOs and other big aid beasts came out last week. Here’s a summary I wrote for the Guardian. Thanks to all those who fed in on earlier drafts. Later today, Oxfam’s Deputy CEO Penny Lawrence will give a semi-official response.

A miasma of existential doubt seems to hang over large chunks of the aid industry, even here in the UK, where I’ve argued  before that a combination of government, NGOs, think tanks, academics, media, public opinion and history constitutes a particularly productive and resilient ‘development cluster’. The doubts materialize in serial bouts of navel-gazing, worrying away about our ‘value add’ and future role (if any).

before that a combination of government, NGOs, think tanks, academics, media, public opinion and history constitutes a particularly productive and resilient ‘development cluster’. The doubts materialize in serial bouts of navel-gazing, worrying away about our ‘value add’ and future role (if any).

So when asked to add to the growing pile of blue sky reports, I decided to approach the topic from a different angle: what does all the stuff I’ve been reading and writing about systems thinking, complexity, power and politics mean for how international NGOs and other big aid beasts function in the future?

The result, published this month by Oxfam, is a discussion paper, Fit For the Future? But if you can’t face its 20 pages, here are some highlights:

Systems thinking raises profound challenges for international NGOs. It highlights the folly of simple, linear interventions and the merits of alternative approaches such as bringing together stakeholders to find joint solutions (convening and brokering), multiple experiments and rapid iteration based on fast feedback and adaptation.

The non-linear nature of most change processes also underlines the need to be able to spot and respond to potentially short-lived windows of opportunity, such as economic or climate shocks or moments of political flux.

Unfortunately, a tradition of central planning, epitomised in the reification of ‘the project’, and a simplistic interpretation of private sector thinking pushes aid agencies towards a linear ‘Fordist‘ (assembly line) approach to going to scale, even though large parts of the private sector have long since abandoned that approach in favour of systems thinking, disruption and innovation.

Unfortunately, a tradition of central planning, epitomised in the reification of ‘the project’, and a simplistic interpretation of private sector thinking pushes aid agencies towards a linear ‘Fordist‘ (assembly line) approach to going to scale, even though large parts of the private sector have long since abandoned that approach in favour of systems thinking, disruption and innovation.

How could international NGOs do better? How can they plan and operate within complex systems, accepting that they cannot know in advance what is going to happen? There are numerous options, most of which would entail a substantial change in working practices.

For Oxfam, this would mean relinquishing a command-and-control approach across all aspects of its work in favour of embracing a systems approach. In terms of investment, this means increasing the ratio of ‘change capital‘ to ‘delivery capital‘.

The paper goes into far more detail on all this, and the risk of trying to cram it all into a blog post is that it ends up sounding like the standard format of the over-excited and extremely vague blue sky paper (‘Everything is changing. Mobile phones! Rise of China! → Everything is speeding up. Instant feedback! Fickle consumers! Shrinking product cycles! → You, in contrast are excruciatingly slow, bureaucratic and out of touch. I spit on you and your logframes →Transform or die!) Umm, thanks.

But if I had to boil it all down, one big question captured a lot of the issues for me: does size matter? According to a recent paper by Hugo Slim: ‘The question of NGO scale will become a major issue in NGO politics over the next twenty years.’ Who is best placed to adopt the new ways of thinking and working: major international NGOs with their advantages of large knowledge bases and economies of scale, more agile ‘guerrilla’ organizations like Global Witness, or single-issue specialists like the Ethical Trading Initiative? Is it the case that ‘you can’t take a supertanker white-water rafting’?

One option might be a ‘conscious uncoupling’ in which large international organizations transition from a supertanker to a

So which is it to be?

flotilla, with a medium-sized mother ship and a fleet of small, independent spin-offs and start-ups. The smaller, more nimble rafts could include individuals rather than the more cumbersome world of projects – backing potential leaders (whether inside the international NGO circle or beyond) with money and support and letting them get on with it.

But there are trade-offs. Scale allows organizations to experiment and exchange ideas between countries and programmes. When it comes to influence, small is seldom beautiful – governments are more likely to listen to bigger players, particularly when they have ‘skin in the game’ in the form of programmes and staff on the ground. What kind of hybrid combination of scale and subsidiarity provides the optimal blend of flexibility and clout?

Should we ever manage to agree on size and structure, the next question is what is stopping us radically changing the way we work? It’s too easy to blame the funders, with their logical frameworks and simplistic demands for tangible and attributable results. Many of the barriers lie within, rooted in institutional practices, ideas about what does/doesn’t work, or just plain ignorance. Any attempt at changing our role will have to begin with a searching and doubtless painful examination of our internal patterns of power and prejudice. Maybe navel gazing isn’t such a waste of time after all.

Oxfam Big Cheese responds to my paper on whether INGOs are ‘Fit for the Future’

In a spirit of transparency, innovation, etc, we thought it might be interesting to print an actual response from Oxfam’s  senior management – this is from

Penny Lawrence

, Oxfam GB’s Deputy Chief Executive.

senior management – this is from

Penny Lawrence

, Oxfam GB’s Deputy Chief Executive.

And what’s Oxfam’s response to Duncan’s challenges? Well it would be churlish, of course, (if understandable) to ask what experience of actually running a large organisation Duncan has!! [DG’s answer – ‘none, thank God’]

I guess the fact that we pay Duncan to criticise our status quo is a reasonably healthy sign of our recognition that Oxfam needs to transform, and will only do so being confident in hearing challenging voices….. but there are real challenges as to how on earth you get there.

Taking more of a ‘systems’ approach is definitely helpful, but even a systems approach still has boundaries and isn’t set up for dealing with unpredictability and uncertainty. Whilst many of us in INGOs would agree that what’s needed is transformational change, we also know there are dangers of throwing every part of our system into uncertainty and change, no matter how appealing it is to be seen as an ‘ecosystem gardener’! Evidence warns us that significant organisational change causes us to look internally for too long. The people who matter, i.e. poor communities, let alone our supporters and staff, tell us they want Oxfam to focus on making a difference in their lives and context, not just our own.

But we have to change to remain relevant and to have any impact or influence in the future….. So can we identify those parts of Oxfam that have to transform and if so, how do we practically deliver such change?

Always a fascinating exercise

Which parts of Oxfam will best serve our goals by remaining hierarchical to deliver efficiently in the future with clear lines of authority; clear ‘roles’, standards and expectations; eg our financial management, compliance with employment laws; the way we deal with management crises or large scale humanitarian responses…….. and which parts of Oxfam will deliver best as flotillas and networks eg. knowledge hubs, developing innovative new business models that really challenge the ‘inertia in our programme development’ etc. Then how do we as one organization combine the supertanker and the flotilla? e.g. finding ways to enable staff to negotiate their roles with leaders and managers in both Oxfam ‘structures’ to get the best out of them and deliver most impact WITH efficiency for poor communities and supporters alike?

These are real leadership and practical organisational challenges. It’s really interesting to see that as many as 300 far sighted US companies, including online shoe retailer Zappos.com, which have gone for more self-organising, self-managing, ‘non-boss’ structures, may have achieved more agile ways of working, but they are struggling with staff disaffection.

For Oxfam we’ve identified 3 or4 steps we want to take.

We absolutely have to get better at learning, failing forward etc, but unless we can really show that this is the path to success on the outside, as well as inside Oxfam, we won’t make much headway. Unless we can convince the public and investors/donors not to expect zero percentage failure rate from aid – that we need to innovate, which involves taking risks and failing more, that their money will be better spent on learning what can influence/go to scale/have most impact, and that may need us to test – learn – adapt (sounds so much more palatable than fail!), then we won’t be able to get traction to transform. We most probably have to do this as a sector, rather than just one agency.

We need to get better at using the opportunities for change that we already have. Our One Oxfam internationalisation process  (all 17 Oxfam affiliates coming together to work as one organization in any given country or issue) offers real opportunities. We have started to identify those parts of Oxfam where our outcomes/clients will benefit most from a more ‘experimental approach’, which will involve a more self-organised structure where leaders provide overall direction and support and teams are then evaluated against the value of learning they generate, and enabled to take risks and experiment. This could be through innovative business models, developing new ways of learning, developing a knowledge network, etc. That’s the aspiration – next we have to work out what kind of cross-Oxfam management structures can deliver it.

(all 17 Oxfam affiliates coming together to work as one organization in any given country or issue) offers real opportunities. We have started to identify those parts of Oxfam where our outcomes/clients will benefit most from a more ‘experimental approach’, which will involve a more self-organised structure where leaders provide overall direction and support and teams are then evaluated against the value of learning they generate, and enabled to take risks and experiment. This could be through innovative business models, developing new ways of learning, developing a knowledge network, etc. That’s the aspiration – next we have to work out what kind of cross-Oxfam management structures can deliver it.

And most importantly, we have to get better at identifying and valuing the skills and attributes of the people we need to attract (and retain) to work in and with Oxfam. People who have more of a ‘quantum’ mindset…..people who can thrive in uncertainty and in not knowing, who can transfer learning to different contexts. And we need to start with really upping our game on recognising and valuing such talent where we already have it. We need to find creative ways to both enable our highly motivated, values driven staff and volunteers to develop their own talents and interests AND our organisational goals and ambitions. We have to be an employer of choice who supports both individual and organisational interests.

June 15, 2015

A long-ignored crisis in development – the collapse in morale among public officials. New UN paper.

News flash: officials are people too. With feelings. If you treat them as untrustworthy scumbags who only do good things for

Teaching in South Sudan

voters and tax payers when they are threatened or offered cash, they are likely to get thoroughly demoralized and may even end up behaving that way. You don’t have to take it from me, you can instead read it in From New Public Management to New Public Passion: Restoring the intrinsic motivation of public officials, written by Max Everest Phillips and Ryan Orange for the thoroughly reputable UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence. Some excerpts:

‘An unacknowledged crisis lurks at the heart of government. It arises from the mismatch that now exists between universal aspirations for excellence in Public Service policies and delivery of services, and the reality in many countries of an increasingly alienated public sector workforce.

An effective public service is at the heart of development. Nowhere can this be seen better than in Singapore. Its people are rightly proud of their nation’s remarkable success. In barely the space of two generations, this small island has progressed from being little more than a fishing village, to its current status as one of the most dynamic cities on earth. This extraordinary achievement has complex causes, one of which is a defining characteristic that the country’s government has wisely nurtured: the strong intrinsic motivation of public officials to deliver in the public interest. Yet the nature of that motivation remains a poorly studied or understood subject.

While all governments are urging their Public Service to do more with less, the first challenge is to admit that the motivation problem exists. The evidence is overwhelming. In the US, the Office of Personnel Management’s Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey for 2013 shows all too clearly that federal government employees, the very people in the world’s most influential country who address the extraordinary mix of macroeconomic uncertainty, rapid social change and technological innovation, are deeply alienated and thoroughly demoralised. In the UK, the annual Civil Service People Survey reveals serious morale problems. Only 40% of British officials in 2013 felt motivated in their job, and only 43% inspired to do their best. These disastrous results are however buried away in a Report that seeks to pretend all is well, rather than confront the problem.

State employees protesting in Cape Town

Many developing countries face similar trends. In Africa, for example, Public Service reforms focused on improving the delivery of services are still premised on the assumption that services can be improved without improving the image, morale and motivation of personnel in the Public Service.

For over a generation, the intrinsic motivation of public officials – to serve the public good – and the sense of self-worth in public sector jobs has been in decline. Politicians and the media since the 1980s have often emphasised the supposed innate superiority of the efficiency and effectiveness of the Private Sector, and discounted the importance of the role of the Public Service in addressing equity and defending public good and national interest. While the unrestrained economic individualism and the alleged superiority of private sector efficiency and market principles was exposed by the financial crisis of 2008 and the private sector’s high profile failure over providing security for the London Olympics, the opportunity to re-emphasise the importance of the public interest has, in general, not been seized. Politicians have more often than not found it easier to tackle the fiscal crisis through irresponsible popularist attacks on the rights of public servants to decent working conditions and adequate pensions, rather than educate the population on the importance for society of properly drafted rules, adequately enforced regulations, fairly collected taxes and high standards in food safety or policing.

The strongest motivation at work is ‘self-actualisation’ – the apex of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the intrinsic satisfaction of  an important and difficult job well done. In public services this is reinforced by sense of national purpose and public good, epitomised by the highly respected intrinsic motivation of the armed forces in countries like the US.

an important and difficult job well done. In public services this is reinforced by sense of national purpose and public good, epitomised by the highly respected intrinsic motivation of the armed forces in countries like the US.

Yet all too often over the last thirty years public service intrinsic motivation has been undermined. New Public Management (NPM) adopted from Principal-Agent Theory the view that the motivation of public officials was aligned to that in the private sector in self-serving economic maximization.

Officials could not be trusted to be self-motivated; they needed to be disciplined by ever growing performance targets and incentivised by performance bonuses, these carrots and sticks were introduced to respond to the NPM philosophy that officials were not really intrinsically motivated by the public good, but instead entirely driven by extrinsic motivation – power, money and perks.

It is no surprise that, at the same time as morale and intrinsic motivation in the public sector has been on the wane, public trust in government has been collapsing. Impartial and effective public administration builds trust between the state and citizenry, and stimulates markets. Trust in government and state legitimacy is not principally created by democracy, the rule of law, or efficiency and effectiveness. Instead, trust and legitimacy are the outcomes of “the impartiality of institutions that exercise government authority.”

Singapore classroom

That impartiality arises from, and reinforces, a public service ethos that motivates officials to deliver public services in accordance with a commitment to serving the public interest. Impartiality of government institutions is linked to higher levels of well-being and promoting interpersonal trust and economic growth. Corruption systematically breaches impartiality and so lowers trust in government institutions.

Although there is a strong correlation between the level of a country’s development and its tax revenues, significant differences across countries at similar stages of development also exist. For example, Jordan and Guatemala have by similar levels of GDP per capita, yet tax revenues in Jordan are around 33% of GDP, while in Guatemala revenues only amount to around 13% of GDP; and while citizens of Ghana are happy to pay their taxes, Serbians are not, requiring the government to spend far more to raise revenues. These differences appear to be the result of trust in the fairness and integrity of their Public Services. So the fiscal crisis is worsened by low morale and motivation in the public sector.

What is to be done? [this bit is less convincing]

All this might seem, indeed is, a daunting challenge. Yet innovative ideas to tackle the problem are emerging. Public services need to stop scorning and start embracing the sense of passion for their mission felt by NGOs. The skill-sets needed in Public service are evolving into something more currently associated with the NGO employee – empathy and compassion. Similarly Public Service offers intellectually interesting work that creates a sense of contributing to the greater good.

Second, embracing Government by Design to inspire that sense of passion. Better decision making by ‘co-creation’ offers a methodology not simply to improve delivery. It is also the most likely way to resurrect the social status and job satisfaction of public service officials.

Third, a ‘whole of government’ approach can ensure that everyone in the public sector knows and is held responsible for, not just their job narrowly defined, but understood in its contribution to the wider national aims. A sense of civic duty will reinforce other important attributes. Autonomy or the freedom within the organization to set one’s own work, satisfaction in working on high-quality work products, improve their skills, respects diversity; the organization manages people fairly, while also promoting the professional development, creativity and empowerment of employees.

While continuous disruptive change in an unprecedented complex environment requires ever more sophisticated policy responses, the officials responsible for tackling these challenges on behalf of citizens and state are disenchanted. The disconnect between the expectations of Public Service capacities to manage a context of ever growing complexity, and the ever deepening despondency of Public Service officials about their sense of self-worth, is rarely acknowledged, let alone honestly addressed. Political leaders fail to promote the status of bureaucracy in society. So the very civil servants delivering essential services and implementing the processes of reform that politicians introduce, feel deep discontent, not so much with pay and conditions as with job satisfaction.

Repeated reorganisations cynically implemented for political reasons have generated deep disquiet in public service employees; the politicization of once proudly neutral civil services has devastated faith in the commitment to protect the long-term national interest. Unchecked, the disconnect between rhetoric and reality will grow ever deeper. So not only must governments learn to do more with less while rebuilding trust of the public and responding to ever growing citizens’ demands; they must rebuild, from an all-time low, the morale of the officials responsible for both front-line services and for central policy formulation.’

Final half-thought – if the NGOs do indeed have morale but not the means to make much of a difference, and the public officials have the means but no morale, wouldn’t some kind of mutual exchange/cooperation make sense?

June 14, 2015

Links I Liked

Wow, more new US immigrants now come from China & India than from Mexico. (Less push, less pull, higher walls,  apparently)

apparently)

Brilliant from Amartya Sen: The economic consequences of austerity. Updating Keynes on the UK election & irrational/ahistorical fear of debt

Exemplary synthesizing from David Evans. 50 papers from a recent World Bank conference on Africa and conflict, grouped by theme and summarized with links. In one post.

Oil revenues as a % of government revenue. Anyone want to compare these to governance indicators?

Alex Evans contrasts the aid and development movement (lost the plot since Make Poverty History) with the climate movement (now found its mojo). Don’t agree with him, but interesting

To understand the human drama of Europe’s migration crisis, read Patrick Kingsley’s brilliant account of one Syrian man’s extraordinary 3 year journey to Sweden

When opening your inbox, do you ever feel like this rabbit jumping across an avalanche? [h/t Geoff Mulgan]

June 11, 2015

A new/better way of measuring the fragility of states?

Tolstoy opened Anna Karenina with the much-quoted line ‘Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its  own way.’ Does the same apply to states?

own way.’ Does the same apply to states?

The OECD’s new report on Fragile States goes some way down that route. Instead of its past (much criticised) single dimension of ‘fragile/non fragile’, it assesses fragility across five dimensions: Violence, Justice, Institutions, Economic Foundations and Resilience. This is definitely progress – with the new framework, it is clear that Benin — vulnerable in resilience and economics — has different development needs than Cambodia — vulnerable in justice and institutions.

There is of course, a price to pay. Instead of a simple list of fragile states, we have a funky, but more complicated, five pointed star.

Only 9 benighted countries tick all five dimensions and end up in the middle of the star:

Central African Republic

Chad

Democratic Republic of Congo

Cote d’Ivoire

Guinea

Haiti

Sudan

Swaziland

Yemen

The others are ranged across different combinations of dimensions.

On the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, Thomas Scherer promptly jumped on the report, claiming that the OECD had got its numbers wrong and that ‘Only 30 of the 70 listed states are classified correctly.’ The OECD replied, defending the data (they said Scherer had used different datasets and years to those used by the OECD, but acknowledging some mistakes with the graphic – I’ve used their cleaned up one).

As always there’s a tension – the more precise you are, the closer you get to saying ‘every state is fragile in its own way’ a la Tolstoy. That might be a better way to acknowledge that these issues apply to all countries, not just a fairly arbitrary subset, but then it becomes subsumed within general discussions of development, whereas the Fragile States lobbyists want to argue that a subset of countries are so fragile that they need special treatment.

Certainly, simply having a fragile/non-fragile binary is too crude, but predictably the choice of the five dimensions and the indicators provoked challenges. Frauke de Weijer of ECDPM felt that the most important gap was external stresses – arms trade, illicit financial flows, organized crime etc.

According to report author Jolanda Profos ‘We have had a lot of feedback on extra dimensions that we should add in 2016, but less feedback on which of the current dimensions we might drop – the problem with a multi-dimensional model of fragility is where do you stop in terms of numbers of issues? It does seem likely that we will try to add a `social dimension’ as the lack of one has been the most consistent area of feedback. But there has also been a suggestion that we should look at the peacebuilding goals.’

At least having a discussion about the different dimensions of fragility allows harder thinking about the whole issue of the role of the state, how effective institutions emerge and the role of aid/other external forces. And if some of the projections are true that fragile states are going to be home to the vast majority of the world’s poor in a few years’ time, thinking about states and institutions is likely to form an ever larger part of the development discussion.

Your views?

June 10, 2015

Reforming FIFA: what can we learn from experience with (other) corrupt autocrats?

This guestie comes from Birmingham University’s Paul Jackson and Heather Marquette

Acres (how many football pitches-worth, we wonder) have been written about the footballing earthquake that followed the arrest of several FIFA officials and the melodramatic end of Sepp Blatter’s reign.

But here’s another angle. In the world of development politics there are striking parallels between Blatter’s leadership of FIFA since 1998 and the modus operandi of the average deranged autocrat. Blatter’s style has had more in common with that of fellow pensioner Robert Mugabe than what might be expected of the manager of an international not-for-profit organisation.

Like Mugabe, Blatter has laid down a rich vein of bizarre quotes. Either of them could have said ‘I am a mountain goat that keeps going and going and going, I cannot be stopped, I just keep going’ or ‘Only God, who appointed me, will remove me.’ Thus far, at least, only one of them has been proved wrong on that point. (Blatter pronounced the first, Mugabe the second, btw)

Sepp jumps the shark

The serious question Blatter’s demise raises is this: the task for soccer fans among Thinking and Working Politically/ Doing Development Differently communities is to identify what TWP can tell us about how things ever got this bad in FIFA; how Blatter was even able to do what he did; and what are the likely paths to lasting reform?

It’s too easy to dismiss Blatter as a crazy dictator from central casting, just as many commentators have with Mugabe. The fact is that the roots of corruption and the type of creature Blatter represents are part of a broader, far more sophisticated system. FIFA may not be a developing nation, but international football has its own complex political economy. As with development programming, any chance of tackling the corruption at FIFA’s heart will demand a lot of ‘thinking and working politically’.

The parallels are profound. Blatter has behaved like any corrupt ruler controlling a post-colonial developing country. When he took charge in 1998, FIFA was still struggling to emerge from the patronising, disempowering and discriminatory rule of football’s European ‘oligarchs’, who had held sway right up until the 1970s. International football also had highly desirable resources – not oil or minerals, of course, but global media ‘reach’ that promised similarly huge potential revenues from sponsorship and advertising.

The methods Blatter used to hang onto power – and the reasons for his success – come tried and tested by leaders such

Football as geopolitics

as Mugabe. Cheap vote-buying; the building and rewarding of a selfish elite whose privilege depends on his power; lots of cash to distribute to those willing to support him. Blatter has been able to do what he’s done for the identical reasons that we’ve seen and still see in certain countries: huge inequality.

As with poor democracies, the quasi-democracy of FIFA, based on one country-one vote, has provided enormous scope for cheap vote-buying. This is deeply rooted in the history of FIFA itself and a power structure developed by richer, elite footballing nations. With Europe’s oligarchs out of the way, Blatter – like every populist leader in a post-colonial context – sought to create his own constituency. Blessed with a massive influx of ‘unearned income’ from TV and other sources, he cemented his power base by sidelining the old elite and spreading the newfound wealth to football federations in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and South and Central America.

Through the lens of political analysis, we can see that corruption is a core element in FIFA’s patron-client relationship. On the face of it, FIFA’s control of its realm’s ‘resources’ pays for better stadia, training facilities for youth teams and better football strips in countries that would never be able to access these funds otherwise. However, this is a patron-client relationship that has provided support for Blatter in return for money for often poor federations – but only if FIFA’s inner circle were allowed to keep some too. This reciprocity is at the heart of corrupt networks, and it binds everyone together.

That’s the easy bit

If we compare FIFA’s model with UEFA or the UK’s Premier League, we can see that here the oligarchs are back in charge. Both of these (relatively) ‘cleaner’ models are wealthy, enjoy full stadia and lots of revenue, but essentially employ the same group of mercenary players transferring between each other. They exclude the overwhelming majority of clubs and have ultimately created a Champions League where only five super-wealthy clubs can ever win. Increasingly, they’re destroying the grassroots of football and also ignoring the fans – the lifeblood of the game.

So, as we move past dwelling on what went wrong, we have to ask what will change – and how. In development, we tend to think that governance people are good at ‘thinking and working politically’, but we’re wrong. Anti-corruption programmes are typically awful at thinking and working politically, and there’s a desperate need to begin to do things differently.

For example, a TWP approach here would tell you that:

Like Mugabe, Blatter didn’t hang onto power so long just because he bungs money at his elite circle. He also created deep patron-client relationships that kept enough of the little guys happy, and it’s hard to see where the collective action needed to bring about reform is likely to come from in these circumstances.

Neither Blatter’s nor Mugabe’s success can be explained simply by ‘greed’ or ‘culture’. It depends on deeply unequal systems that exclude non-elites from accessing power and resources.

This means that the removal of Blatter and his inner circle may go either way; oligarchs and exclusivity are just as likely to take their place as something inclusive and clean. Look at the nations lining up to host the World Cup if the FBI’s investigations take the competition away from corrupt bidders. All the same old elites, with all their fancy existing infrastructure. No one else stands a chance.

A more politically informed understanding tells us that for any transformational change to happen, FIFA needs to do more than chop off its own head. It needs to tackle the inequality that led to this corrupt system in the first place. To really clean up FIFA, richer, elite footballing nations need to give power and resources to the poorer, weaker member federations. Even if it means hosting future World Cups at inconvenient times of the year.

Sorry, was that a pig (sponsored by Mastercard) just flying past…?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers