Duncan Green's Blog, page 160

July 26, 2015

Links I Liked

Unpacking last week’s global soft power index (Britain and Germany top, Mexico and China bottom).

Some particularly tasty wonkwars last week – must be the summer heat:

Deworming: No need to read all the exchanges, because Chris Blattman has spoken. Twice (initial discussion and then very sensible conclusions after a day of online debate); Miguel-Kremer wins: ‘you have to throw so much crazy sh*t to make the result go away that I believe the result even more than when I started’.

Is the FAO massaging the numbers on hunger? Jason Hickel and Thomas Pogge slugging it out in the comments with the FAO’s enjoyably truculent Carlo Cafiero

George Clooney launches ‘The Sentry’ to track down the people funding/profiting from African conflicts. Sounds like a great movie idea.

Why is philanthropy so fixated with social entrepreneurs and so uninterested in social movements? [h/t Tom Murphy]

The Geographical Association has put up a series of 5 short (2-5m) interviews of me ranting in my kitchen, on whether things getting better, our changing understanding of development and what we’re currently worried about. I may even start vlogging. Not with the scary close-ups tho – I fear it’s too late for me to start moisturising…….

Powerful new War Child video. Empathy, sympathy or conflict porn? [h/t Aid Leap]

July 23, 2015

Have the MDGs affected developing country policies and spending? Findings of new 50 country study.

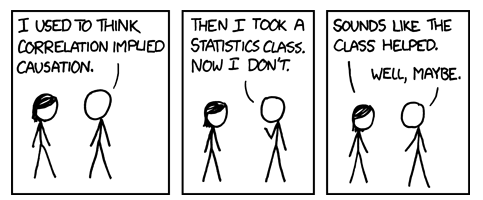

One of the many baffling aspects of the post-2015/Sustainable Development Goal process is how little research there has been on the impact of their predecessor, the Millennium Development Goals. That may sound odd, given how often we hear ‘the MDGs are on/off track’ on poverty, health, education etc, but saying ‘the MDG for poverty reduction has been achieved five years ahead of schedule’ is not at all the same as saying ‘the MDGs caused that poverty reduction’ – a classic case of confusing correlation with causation.

has been on the impact of their predecessor, the Millennium Development Goals. That may sound odd, given how often we hear ‘the MDGs are on/off track’ on poverty, health, education etc, but saying ‘the MDG for poverty reduction has been achieved five years ahead of schedule’ is not at all the same as saying ‘the MDGs caused that poverty reduction’ – a classic case of confusing correlation with causation.

So I gave heartfelt thanks when Columbia University’s Elham Seyedsayamdost got in touch after a previous whinge on this topic, and sent me her draft paper for UNDP which, as far as I know, is the first systematic attempt to look at the impact of the MDGs on national government policy. Here’s the abstract, with my commentary in brackets/italics. The full paper is here: MDG Assessment_ES, and Elham would welcome any feedback (es548[at]columbia[dot]edu):

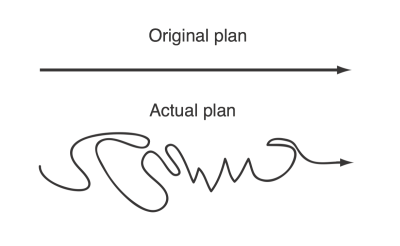

‘This study reviews post‐2005 national development strategies of fifty countries from diverse income groups, geographical locations, human development tiers, and ODA (official aid) levels to assess the extent to which national plans have tailored the Millennium Development Goals to their local contexts. Reviewing PRSPs and non‐PRSP national strategies, it presents a mixed picture. [so it’s about plans and policies, rather than what actually happened in terms of implementation, but it’s still way ahead of anything else I’ve seen]

The encouraging finding is that thirty-two of the development plans under review have either adopted the MDGs as planning and monitoring tools or “localized” them in a meaningful way, using diverse adaptation strategies from changing the target date to setting additional goals, targets and indicators, all the way to integrating MDGs into subnational planning. [OK, so the MDGs have been reflected in national planning documents. That’s a start.]

A high correlation is detected between income group, PRSP status and ODA reliance of countries and their propensity to incorporate the MDGs in their planning instruments. A closer examination of the national plans indicates that PRSP countries are more likely to have aligned their national plans with the MDGs. On the other hand, all the countries that have not aligned their plans with the MDGs belong to the middle‐income countries and are least dependent on ODA. [Not surprising – the more poor/aid dependent a country is, the more it has to listen to donors banging on about the MDGs.]

A high correlation is detected between income group, PRSP status and ODA reliance of countries and their propensity to incorporate the MDGs in their planning instruments. A closer examination of the national plans indicates that PRSP countries are more likely to have aligned their national plans with the MDGs. On the other hand, all the countries that have not aligned their plans with the MDGs belong to the middle‐income countries and are least dependent on ODA. [Not surprising – the more poor/aid dependent a country is, the more it has to listen to donors banging on about the MDGs.]

The correlation between countries’ human development level and their propensity to adopt or adapt the MDGs is similarly quite strong, as the number of MDG‐based national strategies decreases as countries’ HDI increases. The discouraging findings include the dwindling attention national plans pay to the targets pertaining to reproductive health, environment, gender equality beyond education, and maternal health. [Richer countries pay less attention to MDGs, either because they are less aid dependent, or because they find them less relevant – doesn’t bode well for ‘universalism’ in the future]

More disconcerting is the lack of a connection between planning and implementation, as MDG alignment of national strategies is not coterminous with greater pro‐poor or MDG‐oriented policies. In fact, countries that have not integrated MDGs into their national plans are just as likely to allocate government funds to the social sectors as the MDG aligners.’ [Ouch – this is the killer para. Whether MDGs are reflected in plans or not, they do not have any apparent influence on how governments spend their money. She measured this by looking mainly at spending on health (the data was not great, but better than for education) before and after the relevant National Development Strategy and found: ‘the probability of a country increasing its health budget in the years after the publication of their national development plan was the same for countries that had aligned their reports with MDGs and those that had not aligned them.’]

If true (and there’s certainly a need for more research on this issue), the last paragraph is important for the SDG process currently under way – if a simpler, shorter list of MDGs, backed by huge donor resources cannot be  shown to have influenced government spending decisions, what chance has the sprawl of the SDGs (current draft weighing in at 17 goals and 169 targets, see right) got?

shown to have influenced government spending decisions, what chance has the sprawl of the SDGs (current draft weighing in at 17 goals and 169 targets, see right) got?

I hate to say I told you so. Actually, screw that, I love saying I told you so. The post-2015 circus spent a ridiculous amount of time and energy arguing about which baubles to put on its Christmas Tree. It is only now getting to the interesting and important part – ensuring that whatever is agreed is designed to actually influencing the spending and policy decisions of developing country governments. At this point, it ought to have been able to draw on the lessons of the MDG experience; unfortunately, propaganda and wishful thinking seem to have squeezed out serious research on what those lessons actually are. Elham’s paper is at least a start in redressing that.

Oof. I feel better for that.

Please send comments to Elham. And here’s her bio in case you want to give her a job. ‘Elham Seyedsayamdost is a researcher and development professional specializing in the political economy of development. She was recently awarded a PhD in Political Science at Columbia University, where she was a Cordier Fellow at the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA). Her PhD dissertation, titled “A World Without Poverty: Negotiating the Global Development Agenda,” examines the political processes, interests and preferences of international actors in creating the Millennium Development Goals. Previously, she worked for many years on development policy with UNDP and the World Bank. To learn more, visit http://elham.se.’

July 22, 2015

What can NGOs/others learn from DFID’s shift to ‘adaptive development’?

Got back from holiday last week and went straight into a discussion with NGOs and thinktanks on  ‘adaptive development’. Really interesting for several reasons:

‘adaptive development’. Really interesting for several reasons:

I realized there’s a bunch of civil society people (100 people at the seminar, plus 50 online) thinking along parallel lines to donors and academics in the Thinking and Working Politically and Doing Development Differently initiatives, but currently very little cross over. Why is that? I think it’s partly down to being in separate networks, partly scale – big donor money v small NGO projects, partly language (NGOs don’t have much time for all that ‘political settlements’ type jargon) and partly politics/tone – TWP/DDD conversations feel very top down to most NGO types. But the overlap remains huge, and there are big missed opportunities in not bringing the two together. Any volunteers?

Some intriguing thoughts from Pete Vowles, who seems to be doing fantastic work deep in the bowels of DFID. He reckons that the ‘SMART rules’ he helped devise have largely removed the formal barriers to adaptive working, and what remains are the informal barriers, including ‘institutional optimism’, the cultural impossibility of saying ‘we don’t know’ while simultaneously asking for/committing funding, and the fact that people invariably ask for guidance, which can all too easily turn into the next set of tickboxes.

From his position as DFID’s ‘Head of Programme Delivery’, Pete is amassing some interesting first hand experience and great new ideas of what encourages flexible/adaptive programming:

‘Low ambition logframes’ can often lead to better relationships and partnerships than high ambition ones. In the latter, the moment something ‘goes red’ (i.e. targets are missed), the funders jump in, people get defensive, and we’re back to the old ways of working. Maybe the logframe is better seen as a minimum, providing insurance for funders and a foundation for adaptive, flexible work, rather than a maximum?

‘Low ambition logframes’ can often lead to better relationships and partnerships than high ambition ones. In the latter, the moment something ‘goes red’ (i.e. targets are missed), the funders jump in, people get defensive, and we’re back to the old ways of working. Maybe the logframe is better seen as a minimum, providing insurance for funders and a foundation for adaptive, flexible work, rather than a maximum?

DFID is testing different approaches to what this all means in practice, including one nice example of a DFID programme where the team agreed 15 outputs, and then said ‘we’ll pay the partner for delivering any four of them’ in explicit recognition of the different directions the programme could go.

Elsewhere in government (eg around the construction of Heathrow Terminal 5), he’s seen task team approaches where you don’t even know who works for who. What if, say, donors, CSOs and government put together a task team on civilian protection in Eastern DRC, seconded staff, allocated funds and essentially set up a temporary organization? It could even be spun off as a new body with a small endowment if it shows particular promise.

If local knowledge is paramount, as all the TWP/DDD thinking suggests, it’s no good wringing our hands about staff turnover – let’s taken it as a given and think laterally. What about having as standard a panel of local experts (either in country, or with long term engagement there), who act as an institutional memory for amnesiac aid organizations?

The ensuing NGO examples and conversation worried me a bit. I can already see us saying (with some justification) ‘but we’ve always done adaptive development’, and then just trotting out our usual Potemkin Programmes. We need to be pushed hard to identify what is new and what isn’t in all this, and then to try out some new approaches, such as those Pete was talking about. This is where funders and researchers could really help – identify a few countries/sectors where there is buy in from donor national offices, INGOs and national organizations, maybe adopt a task team approach, and monitor carefully what happens next.

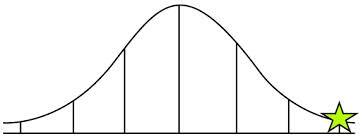

We could also take a dose of our own medicine. If we think positive deviance is the way to go, then let’s start by

Start by studying the starred bit

taking the ‘we’ve been doing this for decades’ community seriously – identify the most adaptive outliers, both in terms of aid programmes, but also countries, communities etc, study them, and see what we can learn. Where are poor communities already particularly resilient to climate change? Has anyone done that?

And the same goes for collaboration – if the lesson of adaptive development is quick, intelligent context and power analysis, but then get stuck in and learn by doing/adapt as you go along, surely the same goes for our attempts to get better at it. Enough talk – we need to set up some experiments and start learning.

As for my input, I did my standard ‘Fit for the Future’ presentation – here’s my talking points (One Pager), focussing on:

Who is ‘we’: Relinquishing Control and Porous Boundaries

How do ‘we’ think and act? Learn to Dance with the System

Imagine there’s no Projects and no ‘development issues’ too

What’s stopping us?

Let me know if you want a post fleshing that out, or a 10m video rant instead

July 21, 2015

Why is there no ‘Fundraisers Without Borders’? Big missing piece in development.

There are an extraordinary number of ‘without borders’ organizations (see here, or an even longer list here) – every  possible activity is catered for, from chemists to clowns (and that’s just the c’s). But one seems to be missing, and it may well be the most useful – why is there no ‘fundraisers without borders’?

possible activity is catered for, from chemists to clowns (and that’s just the c’s). But one seems to be missing, and it may well be the most useful – why is there no ‘fundraisers without borders’?

Mike Edwards argues that ‘we should focus as much attention as possible on strengthening the financial independence of voluntary associations, since dependence on government contracts, foundations or foreign aid is the Achilles’ heel of authentic civic action.’

That is true both because no-one in their right mind would prefer national organizations to be aid dependent, when they could raise funds from their own societies, but also because many of the increasing attacks on ‘civil society space’ are justified by governments on the grounds that CSOs are pawns of foreign funders.

That is true both because no-one in their right mind would prefer national organizations to be aid dependent, when they could raise funds from their own societies, but also because many of the increasing attacks on ‘civil society space’ are justified by governments on the grounds that CSOs are pawns of foreign funders.

It would be unrealistic (and probably disastrous) to just try and export today’s northern fundraising techniques to CSOs in developing countries. Like everything else, fundraising is highly context specific both in terms of culture and history, so helping people identify what works locally and encouraging south-south exchanges of ideas might be better. One such example is Zakat, which has massive potential in any country with a significant Muslim population. Fundraisers without Borders could help by collecting and publicising Zakat-compatible fundraising drives from around the world.

Another is taking advantage of ‘critical junctures’, aka fundraising windows of opportunity. When India passed a law in 2013 obliging corporates to spend 2% of company profits on social responsibility, Fundraisers Without Borders would have scrambled the troops to go and help CSOs and others make sure the law actually got implemented (always a problem in India), and benefited the poor (ditto).

That India example would also involve swapping notes on the politics of fundraising – how to police the fine line  between accepting cash from a corporate, and being coopted onto other people’s agendas.

between accepting cash from a corporate, and being coopted onto other people’s agendas.

INGOs are always keen to recognize and celebrate the long-term rise of the South. We’re adapting our advocacy and other areas of work to that new reality. For example at the recent Addis Financing for Development conference, Oxfam and many others stressed the importance of ‘domestic resource mobilization’, including taxation. Wouldn’t it be a shame if, inadvertently, we failed to support national organizations to raise their own domestic resources?

I ran this past Tom Winslow, Oxfam’s chief cash Hoover, Head of Programme Funding and Partnerships, who cut his teeth raising money for South African CSOs in the 1990s. Here are some of his thoughts:

‘The last thing we need is fundraisers from the north parachuting into southern countries with some idea of “converting the heathen” to best fundraising practice. Instead, we should focus on the incipient movements to build the right enabling environment for civil society fundraising:

‘The last thing we need is fundraisers from the north parachuting into southern countries with some idea of “converting the heathen” to best fundraising practice. Instead, we should focus on the incipient movements to build the right enabling environment for civil society fundraising:

Trends wise, the rise of mobile telephones and the internet have created all sorts of exciting new possibilities for fundraising. Mobile telephone donations are more prevalent in parts of East and Southern Africa than direct debit giving. This is surely going to be a growth area for resource mobilisation in many African countries – provided that the cellular communications companies do not retain the lion’s share of charitable donations (sometimes as high as 50-60%) as their fee.

There are new movements towards indigenous philanthropy that are being spearheaded by groups like Trust Africa

And inevitably…..

(based in Dakar and seed funded by the Ford Foundation) and Inyathelo in South Africa. These organisations have a strong ethos of self help solutions for African problems.

Enlightened donors have made strategic investments in building the fundraising capability of civil society organisations. For many years in South Africa, the late Gerald Kraak of Atlantic Philanthropies provided strategic investments in fund leverage for key civil society organisations in the early years of that country’s democracy – in civil society organisations (like the Legal Resources Centre) and universities (University of Cape Town, Wits, and others) in a conscious attempt to build their capacity to raise funds.

Lawyers have an important part to play in creating the right enabling legal and tax environment for fundraising to flourish. In South Africa, the Legal Resources Centre set up a non-profit organisations law project that worked to create the right statutory environment, including the right tax incentives to encourage public donations towards non-profits. Their work in South Africa spread throughout the region, and is now replicated across the continent by legal practitioners defending, protecting, and carving out space for civil society.

Domestic resource mobilisation strategies should include an agenda for tax exemption for non-profit organisations and tax deductibility on donations to qualified non-profits.

Maybe we should take a leaf out of the Little Red Book and create a generation of barefoot fundraisers instead of fundraisers without borders?’

July 20, 2015

Ricardo Fuentes wants you to apply for his job as Oxfam’s Head of Research – here’s why

Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva (@rivefuentes) is leaving and his job as Head of Research at Oxfam GB is being advertised  (deadline July 30).

(deadline July 30).

I’m inviting you to apply for a job whose highlights include:

You get to exchange blogs with Martin Ravallion.

You get to have the first citation in Joseph Stiglitz’s new book.

You get to have Barack Obama misquote your work (min 4:25).

You get to be on Jon Stewart’s Daily Show, twice.

You get to have films inspired by your work (with Russell Brand, but still).

You get to write letters to The Economist and the Financial Times, and have them published.

You get to be a kind of ghost speech writer for the head of the IMF

And you get to be called the new Duncan Green for a couple of years (OK, that’s not a highlight).

Why? Because I’m heading back to Mexico to take over as Executive Director of Oxfam Mexico. Exciting move, but I’m acutely aware of what I’m leaving behind.

The Head of Research (HoR) covers four main areas of work: campaigns and advocacy; thought leadership; managing the research team and learning from our programmes.

Definitely a candidate

Making sure Campaigns and Advocacy are evidence-based: The HoR is a kind of master of evidence within Oxfam – which can be a tricky position. In this role, you ensure that the organization uses the most up-to-date and credible sources (including academic literature and new databases and methods) in its communications and publications. There is often a tension between being rigorous and making a simple, strong point in campaigns and advocacy – the HoR has to get the balance right, i.e. that we can confidently back up what we say if challenged.

Top example: the trend analysis on the concentration of income and wealth presented at the last two World Economic Fora: Working for the Few and Wealth: Having it all and wanting more and the accompanying killer fact that the world’s 80 richest individuals now own as much as the bottom half of the population – 3.5 billion people (how many times have you heard that one?). For those papers, we used databases put together by respected academics – which was just as well, because we had to defend the results against some forensic scrutiny – including on the famous BBC programme More or Less.

Schmoozing lots of clever people Thought Leadership: The HoR is bombarded with invitations to present at seminars, conferences etc with policy makers, academics and students. These are opportunities to communicate research findings and the accompanying message, but also a great chance to float ideas, develop new arguments and meet some really smart people.

Managing the Team: The HoR often gets plenty of media or wonk glory (something Duncan recognized long ago

Definitely a candidate

when he was in post!). But s/he also manages a small team of (seven) extremely talented and hard-working people who do most of the actual work. The managerial duties are an important part of the job and include representation in different Oxfam internal processes and, very importantly, connecting with other Oxfam researchers across the globe.

Learning from our programmes: One of the main research and learning assets of an organization like Oxfam is its presence in hundreds of communities around the world. This is a goldmine for those trying to understand what works and what doesn’t in international development. Our colleagues in Oxfam’s evaluation team (separate from the Research Team) carry out rigorous impact evaluations for some of Oxfam’s projects. Once the results of the quantitative evaluations are in, Oxfam’s researchers conduct follow-up qualitative analysis to better understand what is behind interesting or surprising project results (whether positive or negative). This is a new but expanding area of work: So far we have conducted follow-ups in Pakistan and Zimbabwe, but several more are in progress.

The job is great, a close-to-perfect mix of thinking and practice. Last week, I said it was one of the best jobs in international development. It wasn’t hyperbole.

To be honest, I’m really only leaving to get away from the British weather and food.

July 19, 2015

Links I Liked

Hi folks, back from hols, and raring to go. Here’s some top links from last week

What people around the world see as the top international threat [h/t Conrad Hackett]

‘Compassion & paternalism could mean helping only 1 million people out of poverty instead of 3 million’. Chris Blattman looks at the evidence on impact v cost on cash, livestock and training

Econo-nerd heaven: Summary of 19 natural experiments in economics. Really interesting and clever.

Britain tops world rankings in ‘soft power’. So renegotiating UK’s deal with Europe  should be a cinch then…..

should be a cinch then…..

Great narrative; shame about the total absence of new commitments on anything. So now it’s on to September’s SDGs summit in New York. Alex Evans sums up last week’s Addis Financing for Development conference

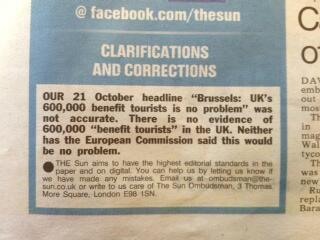

Oops. The Sun admits its ‘600,000 benefit tourists’ story was false. [h/t Charles Edward

Frith]

OK, now this is what I call a wonkwar. Serial NGO baiter Maya Forstater publishes draft paper with CGD on tax and development. Ex CGD-er Alex Cobham describes it as a ‘sustained integrity attack’ on NGO tax campaigners and rebuts at length. Take yr seats, folks.

Greece for Grownups: Adair Turner argues that debt relief is inevitable, as is pension reform. Get over it, everybody.

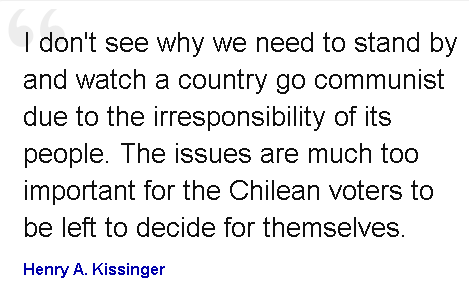

While we’re on Greece, here’s Henry Kissinger on the election of a left-wing government in Chile in 1973, before  helping overthrow it. Remind you of anyone?

helping overthrow it. Remind you of anyone?

July 12, 2015

No Links I Liked today, back next week

By the time you read this, I will already have been on holiday for a few days. Back next week. Here’s me on the beach.

July 9, 2015

Geek Heresy, by Kentaro Toyama: book review

Guest post by Gawain Kripke, Oxfam America’s Director of Policy

I love my smart phone. It’s awesome and it makes me more awesome. I honestly think that my life is much better with it than without. It makes me a better worker – able to review documents, communicate with colleagues, keep projects moving smoothly even when I’m out of the office. It makes me a better citizen – I”m able to read news and events, can report emergencies and contribute to public safety and knowledge by feeding in through networks. I think I’m a better parent – or at least it makes parenting easier. All the logistics of picking up kids and changing schedules are greatly assisted by having my mobile phone. It’s not cool to say so, but I think my mobile phone is a fundamentally empowering technology that helps make me a better person and helps me live a better life.

So, why shouldn’t mobile phones do the same for other people, including poor ones? In researching this idea, I came across Kentaro Toyama. I called him up, and in a long conversation, he batted down my fumbling ideas effortlessly and gracefully. I didn’t know it at the time, but Toyama has emerged as a leading skeptic of technology-led concepts of development. He’s now published Geek Heresy, a book that is worth reading, both for proponents and skeptics of technology in development.

So, why shouldn’t mobile phones do the same for other people, including poor ones? In researching this idea, I came across Kentaro Toyama. I called him up, and in a long conversation, he batted down my fumbling ideas effortlessly and gracefully. I didn’t know it at the time, but Toyama has emerged as a leading skeptic of technology-led concepts of development. He’s now published Geek Heresy, a book that is worth reading, both for proponents and skeptics of technology in development.

Toyama comes to the subject with a background as a technologist, having studied computer science and worked for Microsoft for many years. In 2004 he helped to create Microsoft Research in India, a Bangalore-based computer science laboratory, where he was involved in and observed dozens of initiatives to bring computer technologies to the mass markets – and very poor consumers – of India.

Through that experience and as an influential figure in the ICT4D community, Toyama has unique insight and authority to offer on the subject of technology and development. And his judgement: it’s largely hype. His book tackles example after example of hyped initiatives that didn’t deliver on goals, fell short, went bust. He examines prominent examples like One Laptop Per Child and “Hole in the Wall” to show that they didn’t deliver on their advertised goals.

But very quickly, Toyama jumps the curb on technology and broadens his argument to attack any reductionist, “packaged” intervention. And he shoots at a lot of targets, from micro-credit to social enterprise, from RCTs to computers in the classroom. His argument is that these ideas miss a fundamental reality, which is that any technology or intervention “require(s) a substrate of positive intent and high capacity among individuals and institutions – the exact substrate that in in stunted supply where social challenges persist.”

Observing many pilots and initiatives, Toyama recognizes a pattern that the success or failure of an intervention seems to depend more on the competence and connectivity of the implementing organization than on the technology or specific intervention. Competent organizations, committed and reasonably successful in delivering existing programs – say on improving classroom teaching – can integrate new computers and software successfully. But without that human and institutional capacity, the computers end up gathering dust in a storage closet pretty quickly. Toyama coins a “law of amplification” in which technology or other interventions can enhance existing aspirations and competence, but fall short otherwise.

Toyama spends the latter half of his book exploring the “substrate” and seeking to understand what makes some  people and organizations succeed in their social change missions when others fail. In this, he draws on both professional experience as well as personal, including volunteer work he has done. Toyama is quite evidently an inquisitive, empathetic, and friendly person. He has a lot of examples, usually people he knows personally, drawn from high and low; taxi drivers as well as Microsoft millionaires. He weaves these examples together and distils three qualities that are critical; positive aspiration, discernment and judgment, and discipline or will. He explores each of these to show how they are necessary to the positive development of individuals and, he argues, to organizations and even countries.

people and organizations succeed in their social change missions when others fail. In this, he draws on both professional experience as well as personal, including volunteer work he has done. Toyama is quite evidently an inquisitive, empathetic, and friendly person. He has a lot of examples, usually people he knows personally, drawn from high and low; taxi drivers as well as Microsoft millionaires. He weaves these examples together and distils three qualities that are critical; positive aspiration, discernment and judgment, and discipline or will. He explores each of these to show how they are necessary to the positive development of individuals and, he argues, to organizations and even countries.

This is his recipe for development – building these “intrinsic” qualities. Each can be developed and is necessary. And his primary recommendation is to more fully develop and validate a paradigm of mentorship, another idea he explores and tries to define.

Although I enjoyed the book, I wished for more. In particular, for a book by a technologist, there’s surprisingly little technology in it. Toyama uses the term as generically as I would, not differentiating between different kinds of technology. Since Toyama is pretty deep into it, I had thought I would be getting a bit more insight and texture on technology itself; the application of technologies, the design of technology, the conditions and requirements for technologies to be successful. It would be interesting to learn something about how Toyama – or Microsoft — think about different technologies. But none of that kind of detail is included. Instead, it’s a rather broad critique; well argued but not specific enough that I feel any smarter.

Differentiating between technologies or their applications would be useful especially for practitioners and analysts. But since much of the book is really about the “substrate” the human and institutional context for technology I would have expected – and wanted – more operational guidance on that. How do we evaluate and differentiate? What different strategies and tactics might be used in different circumstances? How do we design better interventions based on an assessment o the intrinsic development of a country, or partner organization, or individual?

Differentiating between technologies or their applications would be useful especially for practitioners and analysts. But since much of the book is really about the “substrate” the human and institutional context for technology I would have expected – and wanted – more operational guidance on that. How do we evaluate and differentiate? What different strategies and tactics might be used in different circumstances? How do we design better interventions based on an assessment o the intrinsic development of a country, or partner organization, or individual?

The book is also missing a political analysis. Toyoma clearly has life experience that would have brought him into close contact with injustices both profound and petty, yet he does not tackle the political dimensions to development, nor to technology. The status quo serves the interests of some, as do technologies. The obstacles people face are not all intrinsic – many are extrinsic and structural. Toyama knows this, and mentions issues like corruption, caste, and the social revolutions. But his examples are all individuals breaking free of their constraints and achieving higher levels of wisdom. His primary recommendation is mentorship, which seems a pretty mild response to some of the horrors the world faces.

Overall, the book is an engaging read. Toyama’s got enough snark to appeal to the skeptical hearts among us, but he’s also clearly a very optimistic, even altruistic, person who chose to make his cause social change and human development when more lucrative career paths were open to him. There are many useful insights, including interesting historical notes in the various parts. It’s a rather personal book, but sources from broader frameworks, psychology and history. But it feels like a first effort, like a scrimmage before the real game. I hope he keeps on with this work because we really need more. We especially need more operational guidance for how to evaluate technologies, but also how to evaluate the “substrate” on which technologies can offer benefits.

July 8, 2015

FEAR/LESS: Standing with women and girls to end violence

Lucia Fry, ActionAid UK‘s Head of Policy, introduces a new report

Listening to the news yesterday, I grimaced as I heard about the latest episode to unfold in the story of the schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria last year: according to news reports, captive girls are being recruited as torturers and combatants by the militant group. 24 hour rolling news and social media have helped generate unprecedented public concern about this case, and others such as those of Malala Yousafzai or Jyoti Singh. Meanwhile high-profile initiatives such as William Hague and Angelina Jolie’s Ending Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative and Justine Greening’s Girl Summit on female genital mutilation and early/forced marriage are evidence of growing interest in the issues from UK decision-makers.

Away from the media glare, however, women and girls continue to experience violence in every country and every context. At home and at work. In anonymous city streets or close-knit communities. In the poorest slums and the richest gated communities. In poor countries and rich ones. This most egregious manifestation of gender inequality affects women’s health, limits their life chances, and prevents them from playing a full part in society. 1 in three women will experience violence in their lifetime, with the most likely perpetrator being their own partner.

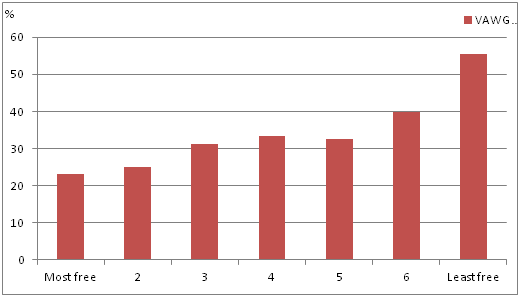

But women and girls are not helpless victims. They are the ones leading the charge against violence, setting up services and demanding change at every level. A ground-breaking 2012 study on violence against women conducted over four decades and in 70 countries revealed that the mobilization of feminist movements is more important for change than the wealth of nations, left-wing political parties, or the number of women politicians. ActionAid’s latest analysis has built on this work, revealing that women in countries with weaker civil rights are around twice as likely to experience violence (see graph below).

Average VAWG prevalence in developing countries by Freedom House Civil Liberties Index Score.

Fearless: standing with women and girls to end violence was published last week as part of our new campaign calling on governments to act now on this widespread human rights abuse. In it, we chart the long list of commitments that women’s activism has demanded and won. We highlight the efforts of women and women’s organisations – sometimes supported by men – to support, organise and resist violence across many sites of struggle. And we analyse the challenges they face. These include funding shortfalls, especially for women’s organisations, the relegation of women to the margins of political life, and a failure to recognise and address the drivers of violence across multiple sectors and policies. Meanwhile women’s collective action is increasingly constrained by political repression, economic inequality and religious fundamentalisms. These issues affect civil society organisations everywhere, of course, but it’s often women’s organisations that experience them first and hardest.

What will it really take to end the violence? As part of our launch week we brought together an unusual group of women for a ‘Strategic Conversation’ on options for a policy change agenda. Unusual, because it was not the predictable and, dare I say it, dry meeting comprised of development professionals. Sure, we had a few of those (including ourselves) but also academics from both classic and more radical perspectives, and activists working both internationally and domestically. We took a critical look at the opportunities presented in 2015 – especially the adoption of the SDGs (including the anticipated target on violence) and the potential role of the UK government in driving forward progress.

The women’s movement has waited for decades for the international community to live up to its human rights  obligations and commitments (notably the establishment of CEDAW and the adoption of the Beijing Platform for Action). So it’s not surprising that there was a fair degree of circumspection about exactly how transformative this moment will be. There was also an honest discussion about some of the contradictions inherent in the UK’s position: seen to be progressive in advocating a gender equality goal in the SDGs and championing action on violence internationally, but questioned over their wider agenda – especially the thorny issue of the private sector in development – and an uneven record at home.

obligations and commitments (notably the establishment of CEDAW and the adoption of the Beijing Platform for Action). So it’s not surprising that there was a fair degree of circumspection about exactly how transformative this moment will be. There was also an honest discussion about some of the contradictions inherent in the UK’s position: seen to be progressive in advocating a gender equality goal in the SDGs and championing action on violence internationally, but questioned over their wider agenda – especially the thorny issue of the private sector in development – and an uneven record at home.

Certain issues were clear, however. Addressing gendered power and the normalization of men’s entitlement to women’s bodies requires donors and national governments to move away from siloed initiatives towards supporting a multi-sectoral approach on all forms of violence. This implies working on prevention of violence as well as its results, and acknowledging the impact of wider policies – including economic policies – that increase women’s exposure to violence. Evidence is important, but influencing what gets researched, by whom and for what intent – including by activists – is vital. Most of all, for action to achieve sustainable change, women’s rights organisations must be given the recognition and support they need. That means governments giving cold hard cash and conceding serious power (and we all know how easy that is to achieve).

July 7, 2015

What should we expect from next year’s World Humanitarian Summit?

Thought all the big development-related summits were scheduled for 2015? Think again. Ed Cairns, Oxfam’s senior

Thought all the big development-related summits were scheduled for 2015? Think again. Ed Cairns, Oxfam’s senior policy adviser on humanitarian advocacy, introduces its new report/shot across the bows of the World Humanitarian Summit, 2016.

policy adviser on humanitarian advocacy, introduces its new report/shot across the bows of the World Humanitarian Summit, 2016.

Humanitarians tend to be practical people, and so when they learn lessons it’s usually from what has failed or succeeded in real crises. Take MSF’s challenge to the world’s ‘inefficient and slow aid system’ on the back of Ebola; or the new Core Humanitarian Standard which really is the culmination of twenty years of evaluations, reviews and soul-searching since the Rwandan refugee crisis in the mid-90s.

So when the UN Secretary-General decided to have a World Humanitarian Summit not learning lessons from any particular crisis, but to ‘make humanitarian action fit’ for the future, it was a bold step.

Oxfam Community Support Workers teach children in West Point, Mon-rovia how important it is to wash their hands to help prevent contracting Ebola, West Point, Monrovia, Liberia, December 2014. Photo: Abbie Trayler-Smith/Oxfam

How could it focus? What could it change? As Christian Aid neatly put it, how could the summit be worth the climb?

Well, we’re now half way through the UN’s ambitious, sprawling consultation process to the Summit in Istanbul in May 2016. We’re getting close to the deadline of 31 July for NGOs, governments and everyone else to post their thoughts before the team under the UN’s new Emergency Relief Coordinator, Stephen O’Brien, draws up the report that will shape what the Summit will actually discuss.

Today it is Oxfam’s turn, in a new report called For Human Dignity. Oxfam’s put out quite a lot of relevant stuff in the last few months – new reports on lessons from Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, Haiti’s devastating earthquake, and even the Indian Ocean tsunami ten years ago. Later this month, my esteemed opposite numbers in Oxfam America, Marc Cohen and Tara Gingerich are publishing their research on how much more international donors must do to support local humanitarian action at the grassroots. For Human Dignity tries to tie these different strands together, and set out some things that the World Humanitarian Summit could and should do.

The promise of swifter, more appropriate and more accountable aid must be kept – not only for disaster response, but also to invest more humanitarian and development aid in reducing the risk of future disasters, and in the long-term recovery from the world’s tragically long list of protracted crises. But it would be wrong for the World Humanitarian Summit to focus solely on how aid agencies and donors must change.

In the preparations for the Summit, millions of words have been written about how to make further administrative changes to international aid. But along the way, some simple truths seem to have been largely forgotten: that injustices, both global and national, lie at the heart of humanitarian crises. To the men, women and children struggling in humanitarian crises, a failed state is one that fails to fulfil its responsibility to ensure its citizens’ access to aid and protection. And to the men, women and children who have just survived this year’s typhoon, flood or other disaster, a failed world is one that allows climate change to overwhelm the world’s most vulnerable people.

One Summit cannot change everything, but the organizers of the World Humanitarian Summit will want to be able to

Oxfam’s warehouse in Saada, Yemen after an airstrike in April 2015. Photo: Oxfam

point at its achievements. For Human Dignity sets out some tests of integrity and success. Here is a handful:

First, the Summit should demand that states are held to account for their international obligations on assistance and protection. Perhaps more than anything else, the Summit would justify its cost if it could really help rekindle outrage at the conflicts, atrocities and war crimes that drive so many humanitarian crises. A new UN Secretary-General will take office a few months after the Summit concludes. The Summit should call on her –hopefully it will be the first female SG – to lead a new international effort to expose the states that now so ruthlessly violate their citizens’ rights to assistance and protection.

Second, the Summit should embrace the idea of ‘subsidiarity’, in which local, national, regional and international humanitarian organisations all have vital roles to play, and in which they all support, wherever possible, the efforts of affected people themselves to cope and recover from crises. International agencies will remain vital; in some crises it’s an illusion to think that local organisations will be able to respond without international support for the foreseeable future. But overall donors should give far more to strengthen the capacity of local and national states and other bodies, such as NGOs to lead humanitarian action. The new Global Humanitarian Assistance report shows that the share of international humanitarian aid given directly to national and local NGOs had fallen to a derisory 0.2 percent in 2014. The time has come to put a figure – at least 10%, and others have argued passionately for more – to raise donor funding to anything near a reasonable level.

A woman and her child take shelter as a jet bombs the streets around her home in, Aleppo, Syria in 2012. Photo: Sam Tarling/Oxfam

Third, there may be many ways to make humanitarian funding more efficient, and Ban Ki-moon has a High Level Panel coming up with ideas on that right now. But beyond everything else, there just needs to be more humanitarian aid – and we should be bolder and blunter about that. In 2013, the world spent $60 billion on ice cream, almost three times as much as on humanitarian aid. Yes, humanitarian aid is rising, but not as fast as climate change and conflicts are driving up the need for it. The UN should bring forward genuinely bold proposals to address this, perhaps with some form of assessed as well as voluntary contributions, a percentage of which could be dedicated to developing local capacity.

Fourth, national governments, funded through progressive taxation, should lead the way in reducing the vast economic and human cost from disasters. But international donors must do far more to support them. The promise to help countries build their resilience to future disasters has not been delivered, with still only a tiny fraction of aid devoted to Disaster Risk Reduction. The Summit should encourage international donors to contribute, by 2020, at least $5 billion of total global annual aid and to help countries vulnerable to disaster build their resilience and reduce the risk of future disasters.

To see our whole For Human Dignity paper, please click here. And please join us in hoping that the Summit really will make some real difference for the millions of people struggling in humanitarian crises.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers