Duncan Green's Blog, page 159

August 6, 2015

Obama’s Afro-mance: A personal reflection by Irungu Houghton

Irungu is an old mate and a redoubtable activist (this post came in late because he ‘Was off school protecting’ –  how cool is that?). He was also two seats away from The Man during Obama’s visit to Kenya last week. Here are some thoughts.

how cool is that?). He was also two seats away from The Man during Obama’s visit to Kenya last week. Here are some thoughts.

The excitement began at least three months before Airforce 1 landed on a spruced up and highly secured Jomo Kenyatta Airport. Over the subsequent weeks, in typical Kenyan fashion, Kenyans on Twitter or #KOT generated no less than ten trending and often hilarious hashtags that included #ObamaInKenya #SomebodyTellCNN #ObamaWelcometoKenyaWhere. But my favourite was #Kiderograss, which teased the Nairobi County Governor for planting grass in the capital a day before President Obama’s arrival. After barely 30 hours in Kenya, Airforce 1 took off, leaving behind both the Kenyan Government and citizens, both very happy at his visit (less typically Kenyan).

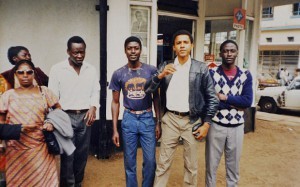

I attended one of the meetings with POTUS at the newly built regional Centre for the Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI). Seventy men, women and girls and one President were restricted to 60 minutes, but at least I got a selfie. Unfortunately the Embassy hasn’t sent it on yet – we had to surrender our phones, so you’ll have to make do with this TV screengrab – that’s me two seats to his left.

Definitely one for the album

That one hour encounter leaves three issues for me.

Firstly, I hope both President Obama and President Kenyatta internalised the sheer diversity, passion and professionalism of the Public Benefit Organisations (or NGOs as they are more commonly called). Rather than leaders of Organisations, what I felt in that room was what informed and active citizens look and sound like. Whether they were innovating community conservancy approaches, building peace, reforming governance, whistleblowing or rescuing girls from female genital mutilation, the activism looked very diverse and resilient in that room that afternoon.

That matters because the last two years of acute tension between the Kenyan State and PBOs have been costly. Mutual trust and suspicion has probably been at their lowest since the early years of the 1990s and the re-establishment of multi-party democracy.

The second issue lies in a growing sense of global connectedness. Fifteen years ago, I remember being coached by an American NGO lobbyist to invoke the memory of the Twin Towers crashing to the ground on September 11 to illustrate the impact of HIV/AIDS in Africa to an American Congressman. The parochialism of the American leadership was probably at an all-time high. Watching President Obama in the last week powerfully rebuke third term-hugging African leaders in their presence at the African Union Headquarters or firmly draw parallels between gay rights and civil rights in Nairobi or gingerly challenge the absence of democratic traditions in Ethiopia, I was left with a greater sense of US policy sophistication with regards to Africa.

Any wider review of US policy to Africa during his tenure would probably be less impressive. The US has missed opportunities to side with African nations on the global issues that have mattered to them on climate, trade, financing for development and tax justice. Which will be the real legacy – 30 hours of Nairobi euphoria, or the previous years of neglect?

Having said this, African change activists seem increasingly connecting and learning from the daily struggles of  ordinary American people as much as from their leadership. We have common challenges. Some of these include speaking and acting for all to be equal under the law. #BlackLivesMatter but so do #SomaliLivesMatter when fighting terrorism in East Africa. We can do more against corruption and the stripping of public spaces, public and natural resources by those with power and privilege.

ordinary American people as much as from their leadership. We have common challenges. Some of these include speaking and acting for all to be equal under the law. #BlackLivesMatter but so do #SomaliLivesMatter when fighting terrorism in East Africa. We can do more against corruption and the stripping of public spaces, public and natural resources by those with power and privilege.

My third lasting impression is that Obama shows what can be achieved by getting involved in the daily grind of formal politics, however frustrating. Kenya is still in a transitional moment. Our practices fall far short of our constitutional vision on integrity, public participation, non-discrimination and devolution. While as PBOs and citizens we must guard our right and responsibility to act independently of the state, we must look for new ways of deepening these freedoms. National self-deprecation and “disruptionist” thinking may have protest value but they have little power to guide us through the transition.

Even cooler on an earlier visit in 1987

I for one, have drawn several lines. The first line is against entertaining “anti-nation” thinking: that the corruption or the ethnic and gender based chauvinism is somehow genetically Kenyan. That we have the leaders we deserve or just the leaders we despise. Like its twin “disruptionist” thinking, this keeps us in protest mode and unable to powerfully create and own constituencies in the public interest. We have got to get more connected to citizens’ collective action around public interest issues. If we do this, we can walk into the middle of the room and inclusively lead.

Irũngũ Houghton is the Kenyan Associate Director for the Society for International Development based in Nairobi. Follow him on @irunguhoughton. For more on his excuse for being late, go to the campaign to protect Kenyan public schools from land-grabbing

August 5, 2015

How do we get better at killing our darlings? Is scale best pursued obliquely? More thoughts on innovation and development

Benjamin Kumpf,

Policy Specialist for Innovation at UNDP, responds to

guest post by James Whitehead

published  on 24 June.

on 24 June.

I found myself nodding to most of James Whitehead’s reflections. Particularly: ”I want to be working with people who are passionate about solving problems at scale rather than magpies obsessed with finding shiny new innovative solutions.” Yet, something seemed to be missing, and something more needed to be said. Let’s start with the missing piece.

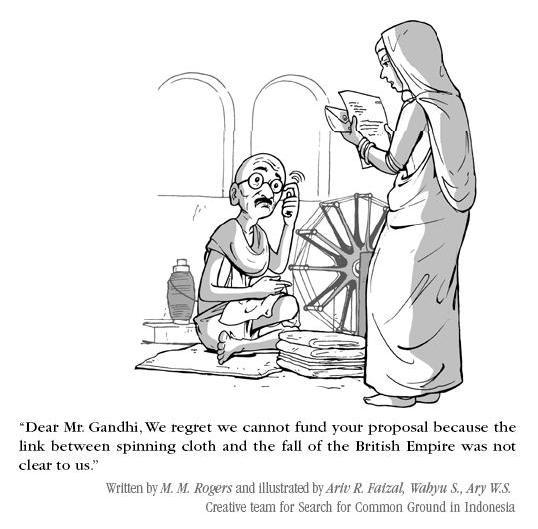

The well-known side of innovation is the creative one. We identify novel ways of doing business, co-create new ideas with the end-users and test them. The flip side of innovation is to discontinue practices for which we do not have sufficient evidence of impact or that are no longer relevant.

Geoff Mulgan illustrated this point in a presentation a few years ago with the 1838 Turner painting of ‘The Fighting Temeraire.’ It depicts a battleship towed into harbor by a new steam-powered tug, to be broken up for scrap. It served well in previous wars but with the advent of new technologies, its time has come.

Geoff Mulgan illustrated this point in a presentation a few years ago with the 1838 Turner painting of ‘The Fighting Temeraire.’ It depicts a battleship towed into harbor by a new steam-powered tug, to be broken up for scrap. It served well in previous wars but with the advent of new technologies, its time has come.

The point here is not about technological progress per se but the readiness and ability to identify what works, what doesn’t and to stop doing what should not be done. A colleague from our team likes to emphasize that “innovation is also about constantly killing your darlings.” Another, somewhat nicer way to say this is: Be Data Driven. This is one of nine principles of innovation for development we endorsed with partners.

Decommissioning beloved ways of working is not easy, including for me. So how can this flip side of innovation be managed? Far from a comprehensive answer, here are two things I’ve learned:

Employing the term ‘failure’ is not conducive to reaching our goals in this context. The word remains popular within the innovation community. But in most conversations with colleagues, talking about failure has not driven or motivated staff and managers to openly share what has not worked and what they have learned. Semantics matter in change management. To get to a more agile and transparent way of working and eventually to have a conversation about decommissioning, we promote ‘calculated risk-taking’, ‘course adaptation’ along with the practice of working out loud

Start with small initiatives that can be prototyped in a relatively short time frame and that generate evidence of impact without threatening ‘old darlings’. Interventions that compare old with new ways are likely to challenge middle management. Middle management is often described as the “permafrost” of organizations and turning it into ‘the volcanic soil for change’ is not easy. What worked for us: introduce new ways of doing business that generate solid evidence and get support from senior management.

This leads me to the statement in Whitehead’s post that needs clarification: ”I want to be working with people who are passionate about solving problems at scale.” Agreed. I also want to work with the driven ones. But is passion enough? Critical thinking, an interest in political analysis and openness to new experiences are other necessary elements in this mix. This includes the openness to question the dominant notion of scale.

Permanent Beta

This notion of scale implies standardization. The assumption that what works in one context can be captured, standardized and transferred to another characterizes too many development innovations, from creative water pumps to countless solar initiatives for rural communities in Africa. The current focus on innovation in development and humanitarian aid might actually do damage with its implicit expectation to find the next big breakthrough that will change the lives of millions. There will be no iPad-esque innovation to end poverty.

The dominant notion of scale underestimates factors such as social norms, power relations between men and women and different social groups and institutions. It also does not adequately take into account the intangible changes that are the result of different actors and organizations developing and testing a new way of working together. Such collaborations are sometimes struggles in the best sense and these struggles can pave the way for longer-term changes. For example, to identify what works to end female-genital mutilation in one community implies taking into account not just the programmatic intervention, but also all the conversations and yes, struggles, within the community, between men and women, opponents and supporters of the practice. This will influence the sustainability of the change and how other social challenges will be addressed in the future. Bypassing such struggles can lead to isomorphic mimicry; institutions and communities adopting ways of working based on an external push without having these practices sufficiently internalized.

James Whitehead writes that “innovation is not the destination, it will occur as the by-product of our combined efforts”. I concur that innovation is a journey, progress in people’s lives is the main destination. But there is a pit stop to that destination: to create the space for constant adaptation in organizations that are predicated upon inflexible multi-year planning instruments, risk aversion and often concepts of scale that promote standardization over adaptation.

Innovation is not likely to be a by-product of our combined efforts if we don’t work on bringing in new ideas and technologies from external sources and introduce design skills to better co-develop solutions with people affected by development challenges. It will not happen if we search for the one big idea. Innovation for development is about the process, not just the outcome. It is about staying in permanent beta. And innovation will not have the desired effect if we don’t say farewell to some of the old battleships along the way. Let’s start with the dominant notion of scale.

August 4, 2015

The Politics of Results and Evidence in International Development: important new book

The results/value for money steamroller grinds on, with aid donors demanding more attention to measurement of  impact. At first sight that’s a good thing – who could be against achieving results and knowing whether you’ve achieved them, right? Step forward Ros Eyben, Chris Roche, Irene Guijt and Cathy Shutt, who take a more sceptical look in a new book, The Politics of Results and Evidence in International Development, with a rather Delphic subtitle – ‘playing the game to change the rules?’

impact. At first sight that’s a good thing – who could be against achieving results and knowing whether you’ve achieved them, right? Step forward Ros Eyben, Chris Roche, Irene Guijt and Cathy Shutt, who take a more sceptical look in a new book, The Politics of Results and Evidence in International Development, with a rather Delphic subtitle – ‘playing the game to change the rules?’

The book develops the themes of the ‘Big Push Forward’ conference in April 2014, and the topics covered in one of the best debates ever on this blog – Ros and Chris in the sceptics corner took on two gung-ho DFID bigwigs, Chris Whitty and Stefan Dercon.

The critics’ view is suggested by an opening poem, Counting Guts, by P Lalitha Kumari after she attended a meeting about results in Bangalore, which includes the line ‘We need to break free of the python grip of mechanical measures.’

The book has chapters from assorted aid workers about the many negative practical and political consequences of implementing the results agenda, including one particularly harrowing account from a Palestinian Disabled People’s Organization that ‘became a stranger in our own project’ due to the demands of donors (the author’s skype presentation was the highlight of the conference).

But what’s interesting is how the authors, and the book, have moved on from initial rejection to positive engagement. Maybe a snappier title would have been ‘Dancing with Pythons’. Irene Guijt’s concluding chapter sets out their thinking on ‘how those seeking to create or maintain space for transformational development can use the results and evidence agenda to better advantage, while minimising problematic consequences’. Here’s how she summarizes the state of the debate:

‘No one disputes the need to seek evidence and understand results. Everyone wants to see clear signs of less poverty, less inequity, less conflict and more sustainability, to understand what has made this possible. Development organizations increasingly seek to understand better what works for who and why – or why not. However, disputes arise around the power dynamics that determine who decides what gets measured, how and and why. The cases in this book bear witness to the experiences of development practitioners who have felt frustrated by the results and evidence protocols and practices that have constrained their ability to pursue transformational development. Such development seeks to change power relations and structures that create and reproduce inequality, injustice and the non-fulfillment of human rights.

And yet some of these cases also recognize that the results agenda can, in theory, open up opportunities for people-centred accountability processes, or promote useful debates about value for money, or shed light on power dynamics using theory of change approaches. Some participants at the Big Push Forward event argued that greater emphasis on evidence has led to more intelligent consumption of data.’

And yet some of these cases also recognize that the results agenda can, in theory, open up opportunities for people-centred accountability processes, or promote useful debates about value for money, or shed light on power dynamics using theory of change approaches. Some participants at the Big Push Forward event argued that greater emphasis on evidence has led to more intelligent consumption of data.’

Guijt identifies the success factors behind what you called call ‘really useful measurement’: the methods employed must be feasible, useful and rigorous, accompanied by autonomy and fairness, generate time and space for reflection on evidence of results, and agile. She goes on to explain the meaning of those rather motherhood and apple pie terms. A few excerpts:

‘Particularly detrimental is the wasted effort invested in collecting incorrect or unused results data’. She argues that by contrast, ‘soft data’ can be particularly useful, such as programme managers personally listening to the views of children and young people.

What is Rigour?: ‘While much of the rigour debate focuses on whether data is rigorous, we should focus on seeking more rigorous thought processes and method selection and use … the term ‘rigour’ needs to be reclaimed beyond narrow method-bound definitions to encompass better inclusion of less powerful voices and improved analysis of power, politics, assumptions and resource allocation’.

‘Results and evidence approaches should strongly emphasize reflection about what is known and what needs further inquiry. Asking people to transcribe results data rather than making sense of that data is increasingly seen as an entrenched problem.’

inquiry. Asking people to transcribe results data rather than making sense of that data is increasingly seen as an entrenched problem.’

She finishes by setting out a positive agenda of seven strategies

‘Develop political astuteness and personal agency’: ‘people’s ability to use the results and evidence agendas positively makes them activists within their organizations, and with funding agencies and partner organizations’

‘Understand dynamic political context and organizational values’: learn to advocate within your own organization

‘Identify and work with what is positive about the results and evidence agenda’: this is the meaning of the book’s subtitle ‘playing the game to change the rules?’

‘Facilitate front-line staff to speak for themselves’: always powerful as a results focus can technocratize issues and diminish the voices of those on the ground

‘Create space for learning and influence’

‘Advocate for collective action’ – the good guys need to work together to perform the kind of ju jitsu on the results agenda set out in the previous strategies

‘Take advantage of emerging opportunities’: don’t just complain; embrace new converts in the mainstream, despite their irritating habit of claiming that they of ‘doing development differently’ first……

Some previous posts on the measurement debate here, here and here

August 3, 2015

How does Change Happen in global commodities markets? The case of Palm Oil

This week’s Economist had an interesting discussion of the change process in the global palm oil industry. I assume all  its claims are highly contested, but still, allow me to walk you through it and what it says about how change happens in one bit of the private sector.

its claims are highly contested, but still, allow me to walk you through it and what it says about how change happens in one bit of the private sector.

The basics: a boom industry with a dire track record of deforestation, labour rights abuses on the plantations, and expulsion of indigenous peoples. Particularly notorious in Indonesia and Malaysia, which between them produce 90% of global output. ‘In all, palm oil has become symbolic of agriculture’s worst excesses.’

2004 and producers, users and NGOs set up the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which sets standards for its members on deforestation etc, backed up by a certification scheme. By 2014 11m tonnes of palm oil – about a fifth of global output, was certified (see graph).

This is where it gets interesting. The RSPO has become a floor as well as an aspirational ceiling – partly driven by some smart campaigning from Greenpeace and others, Nestle, Unilever and some of the other big palm oil using brands pledged to go further. And not just the big brands, either:

‘The watershed was an announcement made in late 2013 by Wilmar, a giant Singaporean trader which handles more than 40% of all globally-traded palm oil. Its trio of promises—no deforestation, no destruction of peatlands, and no exploitation of locals—went some way beyond what the roundtable had required. Wilmar’s decision was encouraged by pressure which campaigners had put on its big customers, such as Kellogg. It was also probably hastened by embarrassment over a severe haze which had cloaked South-East Asia that summer, caused by fires resulting from land clearance in Indonesia.’ [Apparently, our Behind the Brands campaign can take some of the credit  for focusing on making Kellogg a leader on deforestation and other palm oil (and soy) issues when it was initially behind the industry leaders.]

for focusing on making Kellogg a leader on deforestation and other palm oil (and soy) issues when it was initially behind the industry leaders.]

So a) brand leverage affects suppliers too and b) shocks like environmental disasters can be additional drivers of change.

The next step? ‘The tricky problems that remain. Activists who have managed to convince American and European consumers of the palm-oil industry’s misdeeds, for example, have so far had less success persuading Indians and Chinese. Another looming challenge is to improve productivity among the very small, often family-owned, farms that still produce something like one-third of all palm oil.’

And the Economist reckons, rightly, that this is where governments in producer countries, who have so far been keeping their heads down, need to step up. They can help with the enabling environment, for example by improving land registries and amending land use laws to encourage responsible agriculture. As a good liberal rag, the Economist stops there, but of course, governments can go much further in terms of legislation and regulation – if Indonesia declares itself a clean palm oil nation, and legislates accordingly, then it can steal a march on its rivals. Government action can even up the unfairness of companies who go further on commitments paying a significant cost to improve the industry. Their suppliers (who they are pressuring to improve) supply their competitors also, who are ‘free-riding’ off the efforts of the leaders and getting a better supply chain out of it (e.g. lower risks).

Step back from the detail, and the dynamic is interesting, and one I’ve seen at work in other sectors such as the garment industry. Consumer pressure and allies within the industry kick off a multi-stakeholder effort to deal with the most pressing problems; critics say it is all cosmetic and insufficient, and in the process help keep the pressure on; crises and scandals act as critical junctures to move things along; but then the process bangs up against free riders, and firms immune to outside pressure – and that’s where governments need to act. Suddenly, the old ‘voluntary approach v regulation’ dichotomy looks a bit simplistic, don’t you think?

crises and scandals act as critical junctures to move things along; but then the process bangs up against free riders, and firms immune to outside pressure – and that’s where governments need to act. Suddenly, the old ‘voluntary approach v regulation’ dichotomy looks a bit simplistic, don’t you think?

I await the brickbats about my naivety.

And some things that could be relevant, but weren’t in the article:

Have investors (eg fund managers) backed the RSPO or otherwise had an influence?

Has progress stalled now the commodity bubble has burst (see graph)?

Why haven’t any companies or countries done a ‘Jamaican Blue Mountain coffee’ and tried to de-commoditize palm oil? Find five good suppliers, build a long-term arrangement with them, buy all their palm oil, and work closely to make sure that they are clean in every way. Then tell consumers ‘we are structurally and materially different and we have it all under control’.

Wd be interested in hearing from people closer to the industry on whether this is a recognizable portrait and what else is missing.

[Turns out that Oxfam has been pretty involved with the RSPO (e.g. we have a rep on the board). For more background, check out Fair Partnerships and Oxfam Novib’s Programme Scaling up Sustainable Palm Oil]

And here’s the shock-tactic Greenpeace video that helped get some action from Nestle.

August 2, 2015

Links I Liked

Like the new format? Got any comments/suggestions for improvements? Please feed back in comments or vote (over there on the right) so we can try and deal with any glitches

there on the right) so we can try and deal with any glitches

On with the show:

79 nations have never had a woman leader, including most of Africa and the US (tho that could change…..) Latin America, Asia and Europe do a bit better

Being overweight/obese now linked to 2.8m deaths per year via non-communicable diseases like diabetes – more than those from being underweight. Cost is $2trillion. Time for Oxfat to step up?

The Economist has a remarkably one sided paean to the benefits of private schools for the poor. For a rather more balanced (and enjoyable) wonk battle, check out Kevin Watkins v Justin Sandefur on this blog in 2012.

OK, if international migration is a political taboo, how about funding the domestic variety? Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; give a man a bus ticket and you get really good returns on investment. [h/t Laurence Chandy]

It’s the holiday season in the UK – here’s a great selection of photos of underwhelming, rain-sodden Britain. Wonderfully evocative.

It’s the holiday season in the UK – here’s a great selection of photos of underwhelming, rain-sodden Britain. Wonderfully evocative.

The creation of ‘trafficking’ and why it has been disastrous for children in West Africa, by former Anti Slavery International head, Mike Dottridge

And a couple of smart videos:

That viral Shashi Tharoor speech on why Britain should pay reparations for its rule in India – debating masterclass

Simple, funny and brilliant from Steve Gerben. “Americans of Different Eras Discuss Immigration” [h/t Michael Clemens]

July 31, 2015

The blog’s just had a makeover – what do you think?

Our wonderful new webmaster has redesigned the blog to make it more mobile-friendly, provide a better range of  reading etc. Hopefully it will also sort out ongoing problems with people not receiving the email alerts they’ve signed up for.

reading etc. Hopefully it will also sort out ongoing problems with people not receiving the email alerts they’ve signed up for.

So please could you take the following highly sophisticated poll, and send any thoughts, and use the comments to tell us about any remaining glitches or other feedback?

ta

Duncan

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

July 30, 2015

Another good idea from ODI – regular ‘scans’ of hot topics like resilience

The aid and development business is full of tribes – separate ‘epistemic communities’ with their own jargon, shorthands and assumptions, which helps to hermetically isolate them from all the other communities. I try and surf across a few of them, but it’s hard – half the time I have only the vaguest idea what resilience, humanitarian, conflict or livelihoods people are talking about.

The aid and development business is full of tribes – separate ‘epistemic communities’ with their own jargon, shorthands and assumptions, which helps to hermetically isolate them from all the other communities. I try and surf across a few of them, but it’s hard – half the time I have only the vaguest idea what resilience, humanitarian, conflict or livelihoods people are talking about.

So I gave a little whoop of delight (sad, I know) when I saw a new ODI ‘Resilience Scan’ and a more recent quarterly update for 2015 Q1, which aim to keep the rest of us up to date with one of the fuzzwords du jour. Headline findings of the main scan include:

‘Attempts to understand how resilience concepts can be operationalised are proliferating

These include devising strategies to enhance resilience in diverse geographic contexts, including regions, countries, cities, communities and households. They examine the range of potential elements (e.g. rights, resources, planning) that can support resilience to varied disturbances (e.g. heatwaves, floods, food price shocks) to improve outcomes, as well as the range of appropriate governance arrangements to do so (e.g. decentralising water policy, or measures in places of good governance versus post conflict or fragile states). Overall, resilience has moved into the mainstream, especially through international cooperation programming and funding. While conceptually-based operational approaches are growing, so is the looser use of resilience as a generic concept to integrate different sectors and endeavours, or simply as a ‘find and replace’ for adaptation or disaster management.

Three key emerging themes recur throughout the scan.

Operational approaches to building resilience

Measuring resilience

Politics, power and resilience

A huge effort is underway to measure, evaluate, test and gauge resilience across a range of disciplines

A huge effort is underway to measure, evaluate, test and gauge resilience across a range of disciplines

This ranges from efforts to provide qualitative resilience characteristics (e.g. good governance, rights, investment climate) to devising complex formulae for numerical values of resilience. There is a tension between creating measurement proxies that are more case-, and hazard-, specific and those that are cross-comparable. This measurement effort is likely to escalate in 2015 due to growing levels of resilience-centred projects and programmes, and due to the development of targets and indicators for the three big international policy processes on disasters, Sustainable Development Goals and climate change. These must be underpinned by more precise definition and relating the role of resilience in contributing to wider development objectives such as growth, citizen empowerment, good governance, poverty reduction or reduced inequality.

Research and practice on resilience thinking has taken a ‘political turn’

Many research papers argue that greater engagement with politics and power is vital to enhancing resilience. Some focus on the distributional consequences of resilience building actions, and on ensuring benefits for, and inclusion of, the poorest and most vulnerable citizens. Others outline the pitfalls of adopting a less politically-aware and more ‘technocratic’ approach to applying the resilience concept, enabling the term to be co-opted into particular narratives to further specific goals or benefit particular groups (e.g. more than one author discusses how displacement of communities on the pretext of adaptation and enhancing resilience can be used to transfer land to powerful actors).

Resilience is being approached as a more mobilising, less defensive concept

There is a discernible shift in writing, programming and funding mechanisms towards the ability to ‘sell’ resilience as firstly, embodying citizen mobilisation and engagement, secondly, strengthening wider capacities for tackling dynamic shocks and stresses, and thirdly, as an activity providing significant development co-benefits (echoing the ‘Resilience Dividend’ concept). At the same time, many note that the evidence base remains fairly weak, especially over longer timescales.

Operational approaches to resilience, especially complex and interdependency are still needed

A key gap in operationalising resilience thinking is the limited attention to complexity, uncertainty and interdependencies as part of resilience building processes. Some of these complexities and uncertainties arise from the interdependencies between parts of the system, some from the politics inherent in all social systems, some arising from the individual and subjective decision-making logics that can propel or undermine the resilience of vulnerable individuals and wider communities/systems. One way to take this further might be to bring together different areas of resilience practice, such as those working in urban contexts and those examining food security. Enhanced interaction can lead these growing but potentially separate communities of practice to explore common challenges, opportunities and to learn from each other’s successes and failures.

Review of the 2014 Resilience Literature

Our examination of research articles on resilience published in 2014 reveals the breadth and depth of emerging resilience literature. Headlines from these fields include:

Climate change: These papers describe vulnerabilities of specific areas to climate change-induced disturbances, pathways of building resilience, the political economy of climate change-induced displacement and components of successful adaptation and resilience strategies.

Disasters: This literature examines strategies to enhance resilience to disasters, suggesting methods of measuring resilience, and critiques ‘resilience’ as a disaster management strategy due to its lack of engagement with politics and power.

resilient people sound really annoying

Food security and agriculture: Papers in this domain outline ways of measuring resilience to food shocks and examine methods of promoting agricultural resilience.

Conflict: These articles explore how risks from environmental change and armed conflict combine to determine vulnerability and argue that the relationship between climate change and conflict has been analysed too simplistically to date.

Water: Here the focus is on the development of indicators for measuring resilience and on dynamics of water governance that enhance resilience.

Urbanisation: One group of authors emphasises the importance of considering issues of inclusion, rights and power when examining pathways of building urban resilience. A second group lays out the components and elements of urban resilience. A third group presents methods and modalities of building resilience.

Infrastructure and resilience: Key issues in this domain include post-disaster reconstruction, economic metrics of measuring infrastructure resilience and the value of resilience in the sustainable management of the built environment.

Economic resilience: Papers can be broadly divided into two categories – those covering measurement of resilience and those that emphasise the importance of engaging with politics and power for dealing with economic shocks.’

All this, plus recommended twitter handles and blogs (including specific posts), upcoming events and a more formal bibliography of new publications.

The quarterly update does what it says on the tin, highlighting the main contributions from experts, social media and new documents. Standouts include increased discussion in urban and security/conflict circles and more efforts to make the business case for resilience approaches.

I ran this past Debbie Hillier, our in house resilience wallah, who was v excited (not least at how much time this could save her), but also worried:

‘I do have a little niggle that ODI are now effectively writing the entire history/narrative on resilience. I wouldn’t want this to be the only story told, or ODI to be the final arbiter of what is or isn’t significant. It is notable, for example, that all bar one of the experts who have been consulted are white, and most are based in London, others in Thailand and one in India. This is quite a narrow perspective.

It would be good if this could become interactive, that people could propose papers/blogs that they felt had been missed. Of course, this could get messy, but I still think it would be a good check. The consumers would still have the neat ODI version, which is what most people would read, but then also an option to scan through other papers. And people inputting their own suggestions could open up options for ODI to look at, and potentially add quality to what ODI produce next time.’

Even without Debbie’s suggestions, the format is great and alarmingly original – kudos to the Rockefeller Foundation for funding it, and to a large ODI team and other resilience wonks for pulling it together.

Now can we have one on theories of change please? Any other useful candidates (please, not innovation or upscaling)?

July 29, 2015

Fukuyama’s history of the State, Book 2: Political Order and Political Decay

Yesterday I reviewed Volume 1 (from pre-history up to the French Revolution), but before reviewing Political Order and Political Decay, the second volume of Francis Fukuyama’s monumental  history of the state, it’s probably worth asking, why bother?

history of the state, it’s probably worth asking, why bother?

Because whether providing/denying services, freedoms or functioning markets, the state is the most important institution underpinning development, and yet people in the foreign policy and development world operate with hazy and simplistic understandings of where states came from and how they evolve. Another example of historical amnesia, alas.

That blindness was epitomised by the 2003 invasion of Iraq, where the US government ‘seemed to think that democracy and a market economy were default conditions to which the country would automatically revert once Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship was removed.’ Oops.

According to Fukuyama that is a particular problem because ‘If there is a single theme that underlies many of the chapters of this book, it is that there is a political deficit around the world, not of states, but of modern states that are capable, impersonal, well organized and autonomous.’

The second volume picks up from the late 18th Century (French and American Revolutions) and brings us up to the present day. It feels both dryer in style and more fragmented than Volume One, hopping between discussions of the spread of democracy, geographical determinism, political Islam, the role of the Middle Classes and the experiences of various continents and countries in the developing world, before returning to Fukuyama’s two overriding interests – will China’s rise continue, and will anything arrest the US’ ‘political decay’? So instead of trying to identify a single thread, here are some highlights/insights:

The importance of sequencing: ‘Those countries in which democracy preceded modern state building have had much greater problems achieving high quality governance than those that inherited modern states from absolutist times. State building after the advent of democracy is possible, but it often requires mobilization of new social actors and strong political leadership to bring about. This was the story of the United States.’

Clientelism is an early form of democracy: ‘Clientelism should be considered as an early form of democratic accountability and be distinguished from other types of corruption – it is based on a relationship of reciprocity and a degree of democratic accountability between the politician and those who vote for him or her.’

A broader discussion of how countries emerge from clientelism: All modern societies began with patrimonial states. Those that escaped did so through two routes: military competition (ancient China, Prussia, Japan); or peaceful reform based on coalitions of social groups (often new ones created by economic growth) interested in having an efficient, uncorrupt government (Britain, US).

More detail emerges in a fascinating comparison between the construction of effective states in the US and UK:

Maybe an effective state would help?

‘Britain and the US started the 19th Century with patronage-laden governments. In Britain, an aristocrat-dominated, patronage-laden civil service was reformed over a brief 15 year period and replaced by highly educated professional civil servants [in response to failures in the Crimean War and challenge of colonising India]. In the US, patronage was deeply entrenched and took much longer to eradicate: the two political parties, Republican and Democratic, had evolved around the distribution of jobs in the civil service and resisted tenaciously the effort to replace political appointees with merit-based civil servants. It took two generations of continuing political struggle stretching into the early 20th Century to fix this system.’

Part of the explanation of the difference is back to sequencing: ‘the US, by opening up the franchise to all white males a good 60-70 years earlier than Britain, not only pioneered the development of mass Political Parties but also invented the practice of clientilism. Britain by contrast remained a restrictive oligarchy throughout much of the 19th Century and could thus reform its civil service before mass Political Parties were ever tempted to use public office as a currency for buying votes.’

What does all this mean for contemporary development? ‘The widely varying contemporary development outcomes among Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and East Asia were heavily influenced by the nature of indigenous state institutions prior to their contact with the West. Those that had strong institutions earlier were able to re-establish them after a period of disruption, while those that did not continued to struggle…. The least developed parts of the world today are those that lacked either strong indigenous state institutions or transplanted settler-based ones.

In Singapore, the British created not just a port where none had existed before, but also a crown colony and  administrative structure designed to support their interests throughout Southeast Asia. In India, they created a British Indian Army and a higher civil service, institutions that were bequeathed to an independent Indian republic in 1947 and still exist. In Africa, by contrast, they created a system of minimal administration that went under the title of ‘indirect rule’. In so doing, they failed to provide post-independence African states with durable political institutions and laid the ground for subsequent state weaknesses and failure.’

administrative structure designed to support their interests throughout Southeast Asia. In India, they created a British Indian Army and a higher civil service, institutions that were bequeathed to an independent Indian republic in 1947 and still exist. In Africa, by contrast, they created a system of minimal administration that went under the title of ‘indirect rule’. In so doing, they failed to provide post-independence African states with durable political institutions and laid the ground for subsequent state weaknesses and failure.’

Fukuyama accepts that the lessons of history can be pretty discouraging for today’s reformers wondering what to do next when ‘most modern contemporary bureaucracies were established by authoritarian states in their pursuit of national security’, but argues that the US and Britain offer more optimistic and relevant experiences because ‘for better or worse, most contemporary developing countries do not have a realistic option of sequencing [first state, then democracy] and, like the US, have to build strong states in the context of democratic political systems…. No country can realistically try to imitate Prussia, building a strong state through a century and a half of military struggle.’

The book ends with musings on violence, China and the fate of the US:

On Violence: ‘Violence was important in incentivizing political innovation as a historical matter, but it does not remain a necessary condition for reform in cases that come later. These societies have the option of learning from earlier experiences and adapting other models to their own societies.’ Fukuyama argues that economic growth has largely replaced violence and war as a driver of change, because it accelerates the emergence/eclipse of new social and political players. In addition, today’s ‘societies have the option of learning from earlier experiences and adapting other models to their own societies.’

On China: ‘The central issue facing China today is whether, a mere 35 years since the initiation of Deng’s reforms, the Chinese regime is itself now suffering from political decay and losing the autonomy that was the source of its earlier success’

On the US: Fukuyama is in despair about the gridlock of US politics, which he sees as exemplifying the tendency of all political institutions to decay over time. In the US, this has resulted in a ‘vetocracy’ where the country’s traditionally weak central state (designed that way by the Founding Fathers) is unable to budge Congress, subject to rule by the Courts, and unable to adjust to the changing world all around it. He has come a long way from ‘End of History’ triumphalism.

As for its main rival among ‘Big Books on the State’, I found Fukuyama far more nuanced and thoughtful (and less crudely propagandistic) than Why Nations Fail (although both books argue backwards from the desirability of liberal democracy). If you want to see a fairly acrimonious exchange between the authors of both, read Fukuyama’s review of WNF and its authors’ response to the review.

July 28, 2015

The Origins of Political Order: Review of Francis Fukuyama’s impressive history of the state

Ricardo Fuentes has been raving about this book for months, so I packed it in my holiday luggage. Actually it’s two books – The Origins of Political Order takes us from pre-history up to the French Revolution/American Revolution, and the subsequent Political Order and Political Decay brings us up to the present day. They each weigh in at around 500 pages, so hope you won’t mind me taking two posts to review them.

books – The Origins of Political Order takes us from pre-history up to the French Revolution/American Revolution, and the subsequent Political Order and Political Decay brings us up to the present day. They each weigh in at around 500 pages, so hope you won’t mind me taking two posts to review them.

Fukuyama is notorious for his ‘End of History?’ post-Cold War triumphalism, but he’s older, wiser and considerably more nuanced these days. The ambition of the two books is astonishing – nothing less than a history of the birth, evolution and current condition of the state worldwide, with fascinating potted histories of the states both obvious (China, England, Germany, US) and less so (Hungary, Poland, Nigeria).

The starting point is that ‘Poor countries are poor not because they lack resources, but because they lack effective political institutions. It asks (and tries to answer) wonderfully big hairy questions like:

why are some countries (eg Melanesia, parts of Middle East) still tribally organized?

why is China historically centralized, while India isn’t?

why is East Asia so special in its path of authoritarian modernization?

what explains the contrasting fortunes of the US and Latin America?

Fukuyama’s big idea is that political order is based on three pillars: effective centralized states, the rule of law and accountability mechanisms such as democracy and parliaments. ‘The miracle of modern politics’ is achieving a balance between them, which is difficult both to achieve and then to maintain, with many states having one disproportionately stronger than the others, while others achieve it, and then lose it. Its achievement is often accidental, rather than deliberate. Analysing each state’s unique combination of the three pillars helps us understand the strengths, weaknesses and historical trajectories of different countries and empires.

His big concluding paragraph:

‘The three components of a modern political order – a strong and capable state, the state’s subordination to the rule of law, and government accountability to all citizens – had all been established in one or another part of the world by the end of the 18th Century. China had developed a powerful state early on; the rule of law existed in India, the Middle East, and Europe; and in Britain, accountable government appeared for the first time. Political development in the years subsequent to the Battle of Jena (1806) involved the replication of these institutions across the world, but not in their being supplemented by fundamentally new ones. Communism aspired to do this in the 20th Century but has all but disappeared from the world scene in the 21st.’

There is some soul-searching on the sequencing of these three. Successful democracies got the strong state first, then opened up the franchise. If you start with democracy in the absence of an effective state, a spoils war rapidly ensues – as has happened in many countries in Africa, in Fukuyama’s view. But history is not destiny and anyway, telling people who want democracy that they should first demand an undemocratic state is unlikely to wash. Fukuyama finds comfort in the history of the US, which achieved mind-boggling levels of patronage and corruption in the 19th Century, but sorted it out (more or less) over a 50 year period to the 1930s.

The dance between these three components is superimposed upon something even more primordial: the underlying

Nobody expects the Eastern Depot…..

tension between the construction of effective states and the human bonds of kinship – states go through periods of effectiveness, but then ‘neopatrimonialism’ reasserts itself, and political decay ensues as people try and secure jobs, power and wealth for their families and kin. History resembles centuries of whack the mole, as states try to prevent reemergence of kinship and erosion of their control, and they went to some pretty extreme lengths to do so, for example by ensuring there were no families to favour in the first place: ‘By the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), there were an estimated 100,000 eunuchs associated with the palace. From 1420 on, they were organized into an Orwellian secret police organization knows as the Eastern Depot.’ The eunuch battalion’s job was to root out corruption or disobedience among state officials.

And if you think reverting to kin-based and patronage systems is merely of historical interest or confined to today’s developing countries, I have two words for you: Bush v Clinton.

The focus on understanding China is central to the book – China, not Rome or Greece, is the first effective state with a uniform, multilevel administrative bureaucracy, and it achieved it almost two millennia before the US and Europe. But Fukuyama argues that China’s Achilles’ heel is its failure to develop Rule of Law or accountability mechanisms, leading to an extraordinarily top down system that was always vulnerable to the ‘Bad Emperor’ problem (some of the early versions make Mao look like a pussy cat).

Two other threads are worth teasing out: the roles of violence and religion. Religion, it seems, played a central role in the creation of at least two of Fukuyama’s three pillars. It promoted the idea that there were rules and sources of authority above and beyond the ruler of the day, which eventually transmogrified into the rule of law (China’s lack of a transcendental religion is one explanation for its continuing law-lessness). In Europe, ‘‘Two of the three

Pope Gregory VII, driver of change

basic institutions that became crucial to economic modernization – individual freedom of choice with regard to social and property relationships, and political rule limited by transparent and predictable law – were created by a premodern institution, the medieval Church. Only later would these institutions prove useful in the economic sphere.’ You’ll have to go to the book for the fascinating basis of that claim (page 275).

On violence, Fukuyama extends Charles Tilly’s claim that in Europe ‘war made the state and the state made war’ to much of the rest of the world, particularly China, where the original centralized state of the Qin dynasty (3rd Century BC ) was born out of extraordinary bloodshed. Violence or the threat of violence is often necessary to break the hold of incumbents who are blocking social or political change. War drove the rise of nation states in Europe, as conquest and amalgamation both reduced the number of polities from over 500 to today’s couple of dozen, and prompted the creation of strong states to raise taxes and conscripts for war.

That raises an intriguing problem – has the decline in war and violence since the mid 20th Century, which in any other sense we should be celebrating, closed off a vital driver of change? I’ll return to that tomorrow.

July 27, 2015

Learning by un-doing: the magic of immersion

Varja Lipovsek of Twaweza , one of my favourite accountability NGOs, reflects on a recent staff immersion in a Ugandan village. It’s a bit too long, but just too nicely written to cut – sorry!

Take a group of people that are used to talking about development while sitting in offices behind computers, going to meetings at ministries, writing reports and worrying about indicators, and give each some mosquito repellent, a sleeping bag, and directions to a household deep in rural East Africa.

Take a group of people that are used to talking about development while sitting in offices behind computers, going to meetings at ministries, writing reports and worrying about indicators, and give each some mosquito repellent, a sleeping bag, and directions to a household deep in rural East Africa.

Importantly, you do not arm them with any questionnaires, tools, focus group discussion guides or similar baggage. The instructions you give them mostly consist of: hang out, observe, participate, converse, be. In short, do not investigate; learn.

This is what 52 of us did last month; we spread across the Soroti, Kumi and Serere districts of Eastern Uganda, and as we were departing the sanctum of the low-key hotel where we gathered, the anxiety on some colleague’s faces was unmistakable.

My “immersion buddy” and I bumped along first on a boda-boda (a motorbike taxi), then for a couple of hours in a local “taxi” (4 passengers on back seat of a small car, plus a couple of chickens underfoot, 3 in the front seat, plus the driver, baskets tied to the roof) to a village deep in Serere. So deep that a few kilometers further on there were a few fishing hamlets and then the road simply ended on the shores of a vast lake.

We had left paved roads, advertising, health centers, electricity and the din of televisions and local restaurants far behind… to be replaced by fields, churches in half-finished buildings, lots of wattle and straw huts, here and there modest brick houses, more fields, more churches… And police posts with policemen in crisp white uniforms, stark against the muddy red earth, fanning their sweaty brows. And little trade centers – clusters of small businesses which always include one or two fix-it-all places with tools and bicycle pumps; a few shops stocked with soap, plastic flip flops, salt, coca-cola; neat piles of tomatoes, oranges, potatoes arranged on mats ready for sale; a number of open-air “pubs” serving two kinds of local brew; and scores of people coming and going, buying, selling, chatting, laughing, and looking at us.

Everyone knows everyone here, and we don’t know anyone. But not for long: soon we find the house of our hosts, the farmer, orange-grower, bore-hole fixer, church elder, civic educator, local entrepreneur Augustin and his wife Merab and their five children. Here is where we will spend the next four days, which are going to be rich in conversation with Augustin, richer in hand-gestures and shy smiles with Merab, and full of laughing and kicking around a ball with the children.

We will also walk and boda-boda all around the parish and meet the local councilors as well as the elected  chairmen and chairwomen; we will visit schools and talk with teachers and head teachers and listen to their complaints and aspirations; we will happen upon a large meeting under the proverbial tree in a neighboring village and witness robust discussion and collective decision-making in action; we will avoid the clusters of strong, healthy, idle young men already drunk at 11am; we will chat with the pastor, with the taciturn intelligence officer, with the jovial policeman cuddling a baby, with the fishermen hauling glistening silver Nile perch to the weighing station, with the women balancing yellow jerry cans full of water from the village pump…

chairmen and chairwomen; we will visit schools and talk with teachers and head teachers and listen to their complaints and aspirations; we will happen upon a large meeting under the proverbial tree in a neighboring village and witness robust discussion and collective decision-making in action; we will avoid the clusters of strong, healthy, idle young men already drunk at 11am; we will chat with the pastor, with the taciturn intelligence officer, with the jovial policeman cuddling a baby, with the fishermen hauling glistening silver Nile perch to the weighing station, with the women balancing yellow jerry cans full of water from the village pump…

Conversations and encounters similar to ours are taking place all over the three districts where our colleagues have ventured. After four days, we all gather back in the town of Soroti: the anxious faces have turned into delighted ones, parting gifts of fresh mangoes and oranges given by the host families spill out of backpacks (and yes, even a few chickens!), there is a lot of laughter and a nearly unstoppable flow of impressions and anecdotes. Over the next day we take time to share stories, to reflect on our individual experiences and to weave them into a loose tapestry of insights for our organization as a whole.

As an organization, Twaweza focuses on the domains of education and open government. Starting with January this year, we have adopted a new strategy and a revised theory of change. We are civil society; we have our ear to the ground; we are clever. We call ourselves a learning organization. Sometimes, this can sound like a gimmick, but when we do immersion, we are true to that concept. By far the most learning is done on an individual level – the out-of-comfort-zone experience, the closeness and shared experience build with complete strangers, the questioning of one’s own assumptions and norms. But all these experiences would remain just individualized stories if we did not look at them through the lens of our organizational mandate, detecting patterns, reflecting on how we theorize and what we implement. This is the magic of immersion.

We have done this for several years now and each time we focus on a different theme. This year we wanted to explore a core concept in our new strategy, where we hypothesize that transformative change (in education and governance) occurs when there is a constructive overlap and interaction between active citizens and responsive authorities. That magic space called “public agency”: does it exist? And if it does, how big is it, what shape does it take, who is in it, how does it function?

This may sound elementary, but in our experience, the lived reality of most East Africans is that either citizens themselves get things done, or they won’t happen. The government exists mostly in capitals and among the elite, and while some of its long arms do reach deep into the countryside, it’s not focused on service delivery, it’s not focused on people, and it mostly doesn’t work for the public good. It has its own purposes and it’s only a few lucky individuals that can become part of it and benefit from it through coveted government jobs. So the notion of these two parallel worlds coming together over a joint purpose (e.g., these are our children; how do we give them a good education?) seems impossibly utopian. And yet we know, from other countries and contexts that sustainable development (if I dare use these words) is premised on such a joint social contract.

So what did we learn this year? The synthesized, findings are in this report, but here are some of the more visceral insights:

insights:

We observed a general distrust between the government education sector and citizens, and an increased voting with their feet by rural, poor parents who take children out of the government system and enroll them in rural, poor private schools.

On the other hand, this private education system, while trusted by parents to do a good job, is in our observations often failing just as miserably as the public one – and charging high fees to boot.

Parents themselves either do not know, are unable to, or simply do not manage to enhance the learning of their children in other ways, such as engaging with teachers, checking on progress, or monitoring schoolwork at home.

We found that speaking about “citizens” is a little like speaking about “Africans” – a gross overgeneralization, wildly inaccurate and not helpful in guiding our work. On the other hand, in every place there are those individuals who are outgoing and active, and they often hold a variety of titles and roles (my favorite this year: chairman of the borehole, not to be confused with the borehole secretary). These are the people who are identified, time and again, by both international and local NGOs, by churches, and sometimes even by government as “community leaders”; they are brought to workshops, given pamphlets and allowances; they tick the box of grassroots implementation.

In essence, this is local elite capture. But the question is, is this a bad thing – and what is the balance of the local elite working in favor of the local public good, and how do we know when it becomes too exclusive, self-promoting? To tell you the truth, we don’t know.

In this haziness, it is often easier to think about a group of professionals that is united in a specific and identifiable function, such as teachers, or local councilors. At least the job descriptions are clear. But real life is messy and spills out of boxes: take the case of the engaged local young man who set up a private school in his village, which was, for the first time ever in that parish, able to pass 7th grade pupils on the national exam. This school’s director personally helps to coach children around exam time and is widely respected in his community. It turns out, though, that he is also a government teacher in another school quite some kilometers away; the kind of school where classes are overcrowded, teachers are few, and even many of them are routinely absent…

For local government authorities, a good illustration is what a local councilman (appointed, not elected) told us on the topic of accountability. He brought up the term, I asked what he meant by it. “Accountability means that citizens have to know about paying taxes; you would be surprised to know how few of our people pay taxes” he explained. My host nodded vigorously. It seems the people are accountable to the state, rather than the other way around.

Moreover, some of the most powerful authorities exist outside these formal sectors – the most prominent and omnipresent ones were all stripes of religious leaders, clearly wielding influence over decisions taken in schools, in local councils and village meetings. Ignoring them is like trying to influence the mayor of the Vatican while ignoring the Pope.

And there was much more – about unemployment and the numerous young men with college degrees who stumble drunk down dusty village streets at noontime, about gender roles and how clearly boys outnumber the girls in higher school grades, about the deep dislike many people expressed towards the ruling party, and yet in the same breath also the reluctance to endorse any change – if for no other reason, then for the “security” of the country. We struggled hard in the makeshift meeting room of our hotel in Soroti to make sense of these insights and impressions, to organize them into themes, tie the themes to our work.

I am a fan of immersion. But I have to say that as an organization, we did not emerge with sparkling new insights which will now illuminate and guide our work in new directions. We have done immersions in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda for about six years; each time the individual stories are different, but the overarching insights stay largely the same.

Not surprising, actually: lived reality in villages across East Africa has changed little in this time (mobile phones and solar lights notwithstanding). We know that significant, lasting change (if not done in the artificial vacuum of a pilot) takes a long time; so why keep looking for it every year? I struggled with this question on the 11-hour bus ride back to the capital. If this is such a core part of Twaweza being a learning entity, and yet we are learning little of direct impact to the organization, why do it?

Here is my hunch. I think the most significant benefit is not in finding answers, but in asking questions, in the un-doing of old patterns, held truths, stale wisdoms. In having a different reference point, a different perspective. In being an organization in which everyone, from the executive director to the accountant to the manager will have participated equally, and will have a new basket of insights and reflections to draw from.

Here is my hunch. I think the most significant benefit is not in finding answers, but in asking questions, in the un-doing of old patterns, held truths, stale wisdoms. In having a different reference point, a different perspective. In being an organization in which everyone, from the executive director to the accountant to the manager will have participated equally, and will have a new basket of insights and reflections to draw from.

Many of the biggest lessons are personal, some may translate to our work, but it’s the simmering of deeply personal reflections and joint experiences, hard to encapsulate in a neat metric, which adds the most value to organizational thinking. A little like the local brew, ajon, which is prepared in a clay pot, and around which people – friends, strangers – sit, dipping long straws into it and sipping, conversing, laughing. An old friend of mine used to talk about the ferment of ideas; when it comes to immersion, I think he was onto something.

See also previous posts on Twaweza’s impressive approach to evaluation and Robert Chambers on immersion.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers