Stephen Orr's Blog, page 2

November 29, 2023

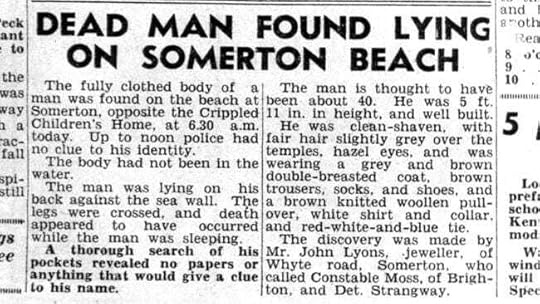

The body at Somerton Beach

On the 30 November 1948 at Adelaide Railway Station a tall, tanned man carrying a brown suitcase bought a second-class ticket for the 10.50 am train to Henley Beach. He walked onto the platform and handed his ticket to the conductor. Then he walked a few steps, or perhaps all the way to the platform, before deciding not to board the train. He left the platform and checked his suitcase at the cloakroom, taking ticket number G52703.

So begins the story of the Somerton ‘mystery man’, one of the strangest unsolved murders (or suicides) in Australian history. To this day no one knows the man’s identity, where he was from, what he was doing at Adelaide Station, what job he had, why he was fascinated with codes, and poetry, if he was a spy or a transvestite, or even how he died.

So, it’s mid-morning, and he’s missed his train. Why? Maybe he was running late, or perhaps he had a change of mind about his destination. Was someone waiting for him at Henley Beach? Someone he couldn’t face? Did he owe them money? Or did he have a change of heart about selling government secrets to a Russian spy? All very dramatic, but nothing’s ruled out with the mystery man. Next, he climbed the concourse stairs to North Terrace, crossed the road and waited at a bus stop outside the Strathmore Hotel, eventually catching the 11.15 am bus to Glenelg and Somerton.

That evening at 7.00 pm a man named John Lyons was walking along Somerton Beach with his wife. They noticed a man lying on the sand with his head against the seawall. As they passed him, they saw him move his right hand as if he were smoking a cigarette or trying to wave to them.

The following morning, December 1, John Lyons returned to the beach for a swim at about 6.30 am and saw the same man sitting motionless against the seawall. Some reports have John Lyons discovering the body and others have him joining a group of people who had already made the discovery. Some sources say the body was discovered fully horizontal (as per the previous evening) and others have the man sitting up against the seawall with his head slumped. Either way, it was John Lyons who rushed home to ring the nearby Brighton Police Station.

Lyons quickly returned to the beach. Constable Moss, the officer-in-charge at Brighton, soon joined him. He found the body of a tall, clean-shaven man in his early forties wearing a coat, brown trousers, white shirt, a knitted pullover and a tie. Moss found no signs of a disturbance or violence. Upon examining the man’s clothes, he noticed all of the labels had been removed. His left arm was stretched out beside his body, but his right arm was bent up. A half-smoked cigarette was found sitting on the right collar of his coat. Apart from the unused railway ticket to Henley Beach, a used bus ticket to Glenelg and cigarettes and matches, his pockets were empty. There was no wallet or keys and the claim to his suitcase was missing.

Most of the newspaper and magazine articles written about this case rule out suicide straight away. Who gets up and shaves just before killing themselves? To counter this we could say that shaving is a habit and if the man was contemplating suicide the familiarity of this routine may have been helping him cope with his decision. The same applies to the jacket and tie. Who dresses up for death? Again, this may have been how men of his class or profession (whatever that was) dressed. Habit. Familiarity. Or maybe this does suggest foul play. After all, why deposit a case you’ll never claim?

The dead man was taken to Royal Adelaide Hospital where it was concluded he died around 2.00 am. Two days later a post-mortem was conducted. The coroner claimed he could find no cause of death. The man’s stomach was congested with blood (a sign of poisoning) but no poisons were found in his body. This might point to a murderer with a good knowledge of poisons but the police at the time had no way of telling what these might be or how they were administered. The post-mortem also showed the man had no puncture marks and his last meal had been a pasty (and who eats a pasty before killing themselves?)

An inquest into the death, handed down in June 1949, stated: ‘The stomach was deeply congested… There was blood mixed with food in the stomach. Both kidneys were congested, and the liver contained a great excess of blood in its vessels.’ Dr John Dwyer, a pathologist who examined the body, suggested that this man’s death could not have been natural. He said the heart had stopped beating, or more correctly, had been stopped, probably by a very uncommon poison – one that had already disappeared from the body.

On the morning of 2 December, The Advertiser reported: ‘A body, believed to be of E.C.Johnson, about 45, of Arthur St, Payneham, was found on Somerton Beach, opposite the Crippled Children’s Home yesterday morning. The discovery was made by Mr J. Lyons, of Whyte Rd, Somerton. Detective H. Strangway and Constable J. Moss are enquiring.’ Mr Johnson contacted police the next day to explain that he was very much alive, thus becoming the first of many dead-ends.

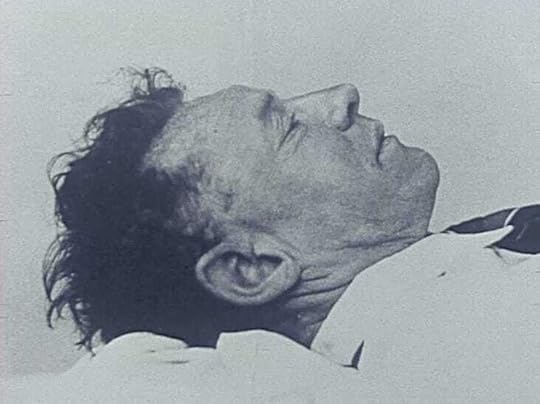

The police fingerprinted the man but couldn’t find a match on their records. There were no scars or distinguishing marks on the body. They distributed the man’s photo to newspapers but there was no response from the public. Soon after they sent photos and fingerprints to every police force in the English-speaking world, without a single positive reply. As the police had no scientific branch in the 1940s the cigarettes found on his body were never tested for poison. The brand of cigarettes (Kensitas) was different to the packet they were found in (Army Club). This may have indicated that the man had borrowed or bought stray cigarettes from someone else or, less likely, had (possibly poisoned) cigarettes substituted without his knowing.

As detectives at the time pointed out, the baffling thing about this case was not the lack of evidence but the surplus. Unfortunately, most of this evidence led nowhere. In fact, much of it was contradictory and distracting. It was as though Agatha Christie had set out to write a novel without knowing the ending. As though she got halfway through and gave up in confusion.

The man was embalmed and kept in a deep freeze at the city morgue. Over the next few months fifty people viewed his body. They claimed he was a long-lost brother, an old bowls partner, a Bulgarian, a missing son. All of these leads were investigated and dismissed.

Adelaide in 1948 was still an innocent place. On a Sunday afternoon you could watch pole-sitting (cupboard-sized rooms mounted on poles, where the brave stayed for days) or the Sunday Advertiser Beach Girl Quest at Glenelg Beach; then you could listen to Clyde Cameron addressing Speaker’s Ring at Botanic Park before wandering up to the City Bridge to watch divers promoting the Advertiser Learn-to-Swim School. During the year Moore’s department store burnt down and the Glenelg jetty was wrecked by a storm that washed HMAS Barcoo ashore at West Beach. Rationing was still in place, and a wave of migrants from Britain, Poland, Latvia and other European countries were moving into Nissen huts in hostels at Pennington, Woodside and Glenelg North. For most of the winter local stockbroker Don Bradman was off in England with his Invincibles, but Premier Tom Playford was firmly in charge, as he would be for another twenty years.

In January 1949 the unclaimed suitcase was discovered at Adelaide Station. The luggage label had been removed. Clothing in the case matched that worn by the man although, again, the labels had been removed. The case contained a roll of thread matching that used to stitch buttons on the man’s trousers; a dressing gown; size seven red felt slippers; four pairs of underpants; two ties; a pair of trousers containing three dry cleaning stubs (1171/1, 4393/3 and 3053/1) inside a pocket; a coat; two shirts; a singlet. The numbers on the stubs were circulated to dry cleaners around the country but no one recognised them, although one suggested they might be of English origin.

Several items carried the name ‘T. Keane’. Police believed this might have been Tommy Keane, a local sailor. Keane couldn’t be located so a few of his old shipmates were taken to view the body. All of them said it wasn’t him.

Police were at a dead-end. This gave the local press licence to invent. The man became a Cold War spy (the Woomera rocket range was still being built), a runaway circus performer or a jilted lover ending it all.

The suitcase also contained a brush used for stencilling and a pair of scissors and a knife with sharpened points. These were similar to those used on merchant ships by Third Officers responsible for stencilling cargo. The case also contained shaving equipment, boot polish, handkerchiefs, a scarf, a towel, a teaspoon and airmail envelopes with no stamps. Detectives concluded he was probably a ‘man of the sea’. They checked every ship in port around Australia but there were no reports of any missing crew.

The big and little toes on the mystery man’s feet were pushed in. The detectives wondered whether he had worn high heeled or pointed shoes. They checked local and interstate ballet schools and theatres but found nothing. The press suggested he might have been a transvestite, but there was no other evidence to support this.

In April 1949, just as the investigation had stalled, a tiny rolled-up fragment from the page of a book was found in the man’s trouser fob pocket with the words ‘Taman Shud’ (‘the end’) on it. An Advertiser reporter told police that this was from a nine-hundred-year-old poem called The Rubaiyat, by Persian poet Omar Khayyam. The poem was about living life to the full and having no regrets. The last verse before these words reads,

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published And when yourself with silver foot shall passText within this block will maintain its original spacing when published Among the Guests Star-scattered on the grassText within this block will maintain its original spacing when published And in your joyous errand reach the spotText within this block will maintain its original spacing when published Where I made one – turn down an empty glass.Police immediately began searching for a copy of The Rubaiyat that had the last page missing. When this latest clue was revealed in the press a local doctor (or perhaps chemist, for some strange reason his identity was never recorded by police) came forward. This man claimed to have found a copy of this book thrown onto the back seat of his car when it was parked outside his home at Somerton Beach on the night of November 30. A clipped section on the final page exactly matched the rolled-up piece of paper in the mystery man’s pocket.

The public was becoming intrigued. Surely this was a Bulgarian transvestite spy pumped full of poison by a secret government agency which had gone to great lengths to confuse the public and police, and to leave everyone with a mystery that wouldn’t so much hide the man’s demise as publicise it internationally. The government had thought it all through, from the selection of an obscure poet to the maiming of the poor man’s feet. From the missed train to the incorrect cigarettes.

Also found written in the back of the doctor’s copy of The Rubaiyat were four cryptic lines and two telephone numbers, one belonging to an ex-army lieutenant, Alf Boxall, and the other, an ex-nurse who lived in Glenelg. She told police she had owned a copy of The Rubaiyat when she lived in Sydney during World War 2, working at the Royal North Shore Hospital, but had given it to a friend named Alf Boxall. She had met Boxall at Sydney’s Clifton Gardens Hotel and, on their second meeting, had given him the book because he was leaving for active service. After the war she’d moved to Melbourne, married, had children and, when contacted by Boxall, declined to continue their relationship. When shown a bust of the dead man the woman couldn’t confirm that it was Alf Boxall.

Still, Alf Boxall became the best contender for mystery man title until he was found very much alive, working in Sydney at the Randwick Bus Depot, still in possession of his copy of The Rubaiyat. Inside the front cover the ex-nurse had copied verse 70 from the book:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published Indeed, indeed, Repentance oft beforeText within this block will maintain its original spacing when published I swore – but was I sober when I swore?Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published And then came Spring, and Rose-in-handText within this block will maintain its original spacing when published My threadbare penitence a-pieces tore.She had then signed it ‘JEstyn’. When questioned about this verse Boxall claimed he didn’t know what significance it had. He told police he had no knowledge of the dead man found on Somerton Beach. ‘Jestyn’, as the nurse became known, asked police to keep her out of the investigation, thereby avoiding any embarrassment to her new family. Police agreed, despite the fact that Jestyn may have been one of their strongest leads.

To be clear, there were two copies of The Rubaiyat, one owned by Boxall (with the copied verse and ‘Jestyn’ signature) and one found in the back seat of the doctor’s car (with the cryptic lines, phone numbers and torn page). What was the connection between these two books? Had the nurse also known the mystery man at some stage, given him a copy of her favourite book and later denied any knowledge of him? If so, how did the mystery man know her (unlisted) phone number and why did he have Boxall’s phone number (according to Boxall they’d never met)? Did the mystery man buy a copy of his ex-girlfriend’s favourite book? Did he find a cue to commit suicide in its poetic, fatalistic lines? Was it a giant coincidence (a rare book, known by very few people in Australia at the time)?

Police believed it strange the mystery man should choose to catch a bus to the suburb where the ex-nurse lived (Somerton is only a few minutes’ walk from Glenelg). Jestyn told police that when she lived in Melbourne in 1948 a strange man had asked a neighbour about her. Was this Alf, or was it the mystery man, trying to follow up on a relationship Jestyn never properly explained? Was Jestyn really trying to disguise the paternity of a child of her present marriage, and is that why police agreed to her request for anonymity?

Jestyn died in 2007 taking, many believe, a sizeable chunk of the mystery with her. Her relationship with Boxall and the Somerton man may still hold the key to solving this mystery.

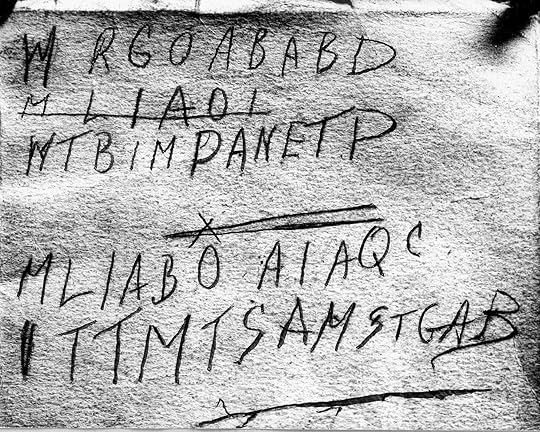

The four cryptic lines written in the doctor’s book were:

Was this the mystery man’s attempt at creating more of a mystery? Another red herring? When these lines were published in newspapers amateur codebreakers the nation over had a crack. Results ranged from, ‘Go & wait by PO. Box L1 1am T TG’ to ‘Wm. Regrets. Going off alone. B.A.B. deceived me too. But I’ve made peace and now expect to pay. My life is a bitter cross over nothing. Also, I’m quite confident I’ve this time made Taman Shud a mystery. St. G.A.B.’ I personally like the latter – the idea that this man knew he was muddying the waters. The only problem is working out how such a long message came from such a short code.

Gerry Feltus, a detective originally involved in this case, was interviewed a few years ago for an article in The Weekend Australian. In reference to these cryptic lines he said, ‘Those letters have to mean something. I try to keep away from it because I know the more you look at it the more you can become obsessed by it.’

The mystery man’s body was buried in Adelaide’s West Terrace cemetery in 1949. The headstone reads: ‘Here lies the unknown man who was found at Somerton Beach, 1 December, 1948’. The South Australian Grandstand Bookmaker’s Association paid for the burial and the Salvation Army conducted the service. Three days after the burial the inquest into the mystery man’s death was reconvened but the coroner couldn’t make any finding on the man’s identity or cause of death. He pointed out that the man seen alive by John Lyons on Somerton Beach on the evening of November 30 wasn’t necessarily the man found the next morning, as no one had seen his face.

The brown suitcase was destroyed in 1986 and many statements have been lost from the police file in the intervening years. A bust of the man (which still contains hair fibres imbedded in the plaster) is now in the Adelaide Police Museum. Gerry Feltus believes that modern DNA techniques may still help reveal the man’s identity.

Feltus, along with Len Brown, another detective who worked on the case, believe the stranger may have been from the Balkan states. In 1948 these countries were mostly under Communist rule, and they were unable to make inquiries there. Brown believes it was a case of suicide. He puts the secrecy down to the fact that the man wouldn’t want to have disgraced his family. Feltus believes it’s more than this. ‘Why would he go to the elaborate lengths he did and create this mystery if he wanted to kill himself?’ he said. Regarding ‘Taman Shud’ he says, ‘Perhaps someone gave him the piece of paper and said, Go to the beach and meet a guy who has the rest of the book… Did he meet him? Or perhaps the book was thrown into the car because he knew it would be found and get publicity and the person for whom the code letters were meant would read them in the press.’

One popular theory states that the mystery man was a spy. In April 1947, the US Army’s Signal Intelligence Service discovered that top-secret material had been leaked to the Soviet Embassy in Canberra from Australia’s Department of External Affairs. The US responded by banning the transfer of sensitive information to Australia from the US, and Australia reacted by setting up the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). Was Alf Boxall involved in Australian military intelligence, and did he have something to do with the mystery man’s death? Was the mystery man a Soviet or Eastern-bloc spy? Had he been to Woomera, gathered information, and returned to Adelaide, where he was murdered?

There are dozens of questions that remain unanswered. Was the man a local? If so, why did no one recognise him? If not, why did no one recall his arrival, or if he drove, where was his car? The man was clean-shaven with a cutthroat razor and strap. If he was a recent arrival, where did he shave? There were no facilities at Adelaide Station and no hotels or boarding houses recalled the man. Why did he not keep the stub for his suitcase? Did he give it to a second party? What did the mystery man do at Somerton Beach (if indeed he was at the beach) from lunchtime on November 30 until his discovery?

It’s easy to imagine the mystery man’s final hours. I can see him sitting on the Somerton bus reading The Rubaiyat, scribbling the four cryptic lines with a mischievous grin. I can see him tearing the final page and putting the piece of paper in his fob pocket, preparing himself psychologically for his own end. I can see him getting off the bus and walking down the road, feeling in his pocket for the poison he’d bought on board his merchant ship. Perhaps it was intended for his unfaithful lover (did she live at Henley Beach?) but he’d decided to use it himself. I can see him sitting on the beach looking out, thinking of his distant home, wondering, What’s the use of going on, it’s just more struggle? I can see him waving at John Lyons and then later, before the cold of evening, getting up and walking to a deli, buying a pasty, returning to the beach and eating it. And then waiting for night, for an empty beach, unwrapping the poison and placing it on his tongue. Closing his eyes. Losing consciousness as his fingers opened and the poison wrapper blew away down the beach.

Or maybe I’m wrong.

Information still comes to light. Years after the man’s death a female receptionist at the Strathmore Hotel on North Terrace said she’d become suspicious (it was never explained why) of a well-spoken man who was staying in room twenty-one days before the body’s discovery. She had ordered a search of his room and found a black case containing what she thought was a hypodermic needle. The man checked out on November 29 or 30. Again, more questions. If she’d been so suspicious, why didn’t she come forward at the time? Was the man just a surgeon, a doctor, a diabetic, a drug addict, or was he the source of the mystery man’s poison, or poisoning?

In June 1949 the body of a two-year-old boy, Clive Mangnoson, was found in a sack in sand-dunes at Largs Bay, a few kilometres north of Somerton. His father, Keith Mangnoson, was found beside him, unconscious. The father was given medical attention and eventually transferred to a mental hospital. Both he and his son had been missing for four days, and the coroner determined that Clive had been dead for approximately two days before he and his father were discovered.

Keith Mangnoson’s wife, Roma, said she believed the disappearance of her husband and son had something to do with Keith’s attempt to identify the mystery man. Mangnoson believed he was Carl Thompsen, a man he’d worked with in Renmark in the late 1930s. After Keith had approached the police she’d seen a man lurking around their house in Cheapside Street, Largs Bay, and had almost been run down by a masked man driving a cream-coloured car. She stated, ‘The car stopped and a man with a khaki handkerchief over his face told (me) to keep away from the police, or else.’

Despite forensic testing, the police were never able to ascertain the cause of Clive Mangnoson’s death. Had the boy been killed with a similar ‘invisible’ poison to the mystery man? Had his father, hiding a secret he shared with the mystery man, suffered a mental breakdown, taken his son, killed him, and attempted to kill himself? Who was the masked man? And what about the common thread of beaches and sand dunes?

For years after the mystery man’s burial there were reports of an old woman putting flowers on his grave. Police even staked out the grave but never found her. Was she just a good Samaritan, or perhaps the mystery man’s Henley Beach lover?

One thing’s for certain – some stories don’t have an ending, and when we finally realise this, we turn them into myth. But the mystery man was a breathing, dreaming, walking human being, full of urges, frustrations and problems we can’t help him with anymore. When we talk about him, we talk about ourselves – and the great stage-managed mystery of our own life and death.

June 2, 2023

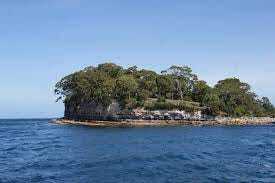

Point Puer Boys' Prison

Point Puer Boys’ Prison (1834-1849)

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Imagine: ten years old, brought up in the East End of Victorian London, abandoned by your parents, left to find your own Artful Dodger and make your own way in the world. Your first picked pocket, or break in, and you’re up in front of the ‘beak’. He looks at you and tells you you’re no good and suggests a few years in Hobart Town might do some good. Five months later you and a hundred other 10–14-year-olds are lined up in the bleak Southern capital and inspected by farmers and factory owners in search of free labour. After a hellish journey, packed into a dark hold, fed on gruel and biscuits (just in case you were in any sort of condition) the Board has decided you are, after all, no good for coal mining, quarrying or building roads. So, it’s back to the barracks, and the thieves and murderers destined for the Port Arthur penal colony.

By now you’re learning how to protect yourself from abuse, obtain your share of food and water, stay sane at an age when other children are playing with tin soldiers and paper windmills. Soon, you learn you’ll be sent to Point Puer Boys’ Prison. The name is muttered as some sort of omen, or warning, or damnation. You realise it doesn’t sound good.

In 1843 Benjamin Horne visited Point Puer to observe and write a report on conditions for the Governor, Sir John Franklin. His notes make it clear that this wasn’t a place for the faint-hearted:

In the sleeping apartments lights are kept burning during the night, and they [the boys] are constantly watched by Overseers, but the efficiency of this system must depend wholly upon the moral character and vigilance of these Officers. Sometimes the Overseer relaxes his vigilance and falls asleep, and, if he is not a favourite with the boys, they put out the lights and invert and empty a night-tub over his head and shoulders. This trick which is called ‘Crowning the Overseer’ has occurred once during my visit.

Point Puer was established to cater for boys who had been sentenced to transportation. It’s difficult for us to fathom a government and judiciary who could treat children as the worst sorts of criminals. To some extent, English society thought itself better off without these ‘types’, but there was also an idea that these boys needed to be saved from themselves. They could be reformed, taught to fix shoes, bind books, mill wood and contribute to the future of their new colonial home. Horne believed the juvenile prisoner is ‘deplorably ignorant of religious and moral duties … or of reading and understanding good books …’ In other words, these ‘rascals’ just needed a firm hand.

Thirteen-year-old Walter Paisley was sentenced to seven years’ transportation for housebreaking. He was one of Point Puer’s first arrivals. He was no angel. During his time at the prison forty-four charges were brought against him for insubordination, stealing and assaulting overseers and superintendents. Mostly, the punishment was solitary confinement, but this didn’t bother him. A few weeks after his arrival he was sentenced to the cells for a week for insubordination. A few months later he was back for smuggling tobacco. He sat singing, shouting obscenities, determined to make life difficult for his captors. After his release he struck the schoolmaster, stole a chicken from the superintendent’s garden and assaulted boys who had given evidence against him.

The first few years at Point Puer were tough. Discipline was strict. The boys were mostly a product of the slums within growing cities such as London, Birmingham and Manchester. Either this, or used as free farm labour from an early age. Despite not having chosen their own path through childhood, they were seen by authorities as ‘very depraved and difficult to manage, perhaps more so than grown men.’

Boys were up at 5 am, rolling their mattresses and washing in tanks of Point Puer’s scarce water. Six am meant prayers (‘Singing is not taught, and the consequence is that this part of the Divine Service is very badly conducted. In fact, the screaming is almost intolerable to any person whose ears have not by rendered callous by hearing it continually’) Then:

½ past 6 Breakfast

½ past 7 Musters

8 to 12 Workshops and General Labor

12 to 1 Play and washing for dinner

1 Dinner

¼ to 2 Muster for School and Work

2 o’clock One half goes to School and the other half to work on alternate days from 2 to ½ past 5

½ past 6 Supper

7 to 8 In summer play. During the winter Months they are mustered earlier and some time is spent in reading aloud to them in their barracks etc.

8 o’clock General muster in the different buildings. After this reading the scriptures and prayer

By 9 o’clock All are in bed

If it was warm enough the boys could take a ‘sea bath’ between five and six in the morning (tide permitting). A near freezing dip would be enough to get anyone’s day started. As with Port Arthur, the location of Point Puer, on a fat finger of land stretching out into the bay, was meant to deter any thoughts of escape. The south-eastern tip of Tasmania is rugged, ocean-beaten, wind-swept, heavily wooded. On the journey from Hobart boys would have passed Two Island, Curio, Tunnel and Raoul Bays, the latter with its 180 m high dolerite columns soaring into the sub-Arctic sky as some sort of warning of what’s to come. At one point Cape Raoul had its own signal station. Years after it was closed (due to inaccessibility) the skeleton of an escaped convict who’d starved to death was found in the Signalman’s hut.

The boys would have then sailed north past heavily wooded country, eventually arriving at their new home, a rocky peninsula suggestively pointing to the Isle of the Dead (Port Arthur’s burial island). They would have looked across Carnarvon Bay and seen Port Arthur itself, its grim, chiselled face warning them there would be no escape.

Their prison was surrounded on three sides by water, and strong currents that carried small, underfed bodies out to sea. This ‘Junior Port Arthur’ was an early version of San Francisco’s Alcatraz Prison. To the west, sheer cliffs and a rock pavement ensured no one was going anywhere.

Point Puer featured in Marcus Clarke’s novel For the Term of His Natural Life. The story was published in the Australian Journal between 1870 -1872. It concerns Rufus Dawes, a young man transported for a murder he didn’t commit. The loosely connected stories outline his struggles as a convict in Van Diemen’s Land. In the novel, Clarke introduces us to 12-year-old Peter Brown, a ‘refractory little thief’ who jumps off the Point Puer rocks and drowns himself. Clarke’s sense of drama was laced with social conscience. ‘Just so! The magnificent system starved and tortured a child of twelve until he killed himself. That was the way of it.’ His indignant superintendent, Burgess, is enraged at this ‘jumping off’. ‘If he could by any possibility have brought the corpse of poor little Peter Brown to life again, he would have soundly whipped it for impertinence …’

Childhood suicide was probably the extreme. Many boys tried to escape but the road back to Port Arthur was patrolled by soldiers stationed in a barracks on a ‘demarcation’ line between the two prisons. There were three recorded successes, but there were probably more, and probably more small bodies lost in the bush. One Commandant, William Champ, described the location as a ‘bleak, barren spot without water, wood for fuel, or an inch of soil …’

Horne agreed. His report said that water was brought from the mainland in a ditch but ‘from the porous nature of the soil this could scarcely have succeeded … At present water is brought from Port Arthur by sea …’ He described how an attempt had been made to improve the soil using ‘seaweed, night soil etc’. Also, ‘the wood on the Point is exhausted and firewood is also brought from the Penal settlement.’

None of this was good news for the boys.

Rations (daily)

¾ lb flour

¾ lb fresh or salt meat

Dinner (lunch)

1 Pint Soup

12 oz meat, reduced by boiling and extraction of bone to 6 oz

9 oz bread

9 oz dumpling

Supper (dinner)

1 Pint gruel

9 oz bread

Mostly, the Point Puer inmates were not misunderstood angels. Several months after Horne forwarded his report to the Governor an overseer was murdered by two boys. Discipline ranged from confinement to cells to solitary confinement on bread and water for up to fourteen days, corporal punishment (up to 36 lashes) and, ‘in very bad cases’, transfer to Port Arthur itself. It’s hard to imagine how bad a boy would have to be to warrant removal to one of the toughest prisons in the world. The weekly Magistrate’s visit attracted between ten and sixty hearings. Horne explained, ‘A removal to the Jail is very little feared by a bad boy … A boy who has perhaps a little moral principle remaining is sent to the Jail for two or three Months, associates daily with other boys still worse than himself, and returns to the General Class thoroughly corrupted.’

He goes on to explain the pointlessness of corporal punishment. ‘It tends to degrade and harden, and after having been twice or thrice inflicted is evidently useless.’

There was a growing view in England, America and Australia that locking up increasing numbers of ‘criminals’ would achieve nothing. Dickens had already visited American prisons to study new ways forward for the British system, full to overflowing, cruel, heartless, sucking in millions of poor and spitting them out in the Antipodes. Here was Oliver twist in Van Diemen’s Land. Meanwhile, William Blake and the Romantics were de-industrialising childhood in poems such as Little Boy Lost.

The weeping child could not be heard,

The weeping parents wept in vain:

They stripped him to his little shirt,

And bound him in an iron chain.

Years later, Marcus Clarke would leave no doubt what sent little Peter Brown to his death: ‘20th November, disorderly conduct, 12 lashes. 24th November, insolence to hospital attendant, diet reduced. 4th December, stealing cap from another prisoner, 12 lashes. 15th December, absenting himself from roll call, two days’ cells. 23rd December, insolence and insubordination, two days’ cells. 8th January, insolence and insubordination, 12 lashes.’

And so it continues. Later in the book, Brown’s friends, Tommy and Billy, succumb to the same horror: ‘And so the two babies knelt on the brink of the cliff, and raising their bound hands together, looked up at the sky, and ungrammatically said, “Lord, have pity on we two fatherless children!” and then they kidded each other, and “did it”.’

Horne explained that instruction ‘in trades and various industrial employment is valuable both as a means of reforming the juvenile delinquent and of preparing him after his liberation to preserve his subsistence by honest labour.’ Colonial authorities believed the problem was the boys’ ‘love of wandering’. If they could be trained and kept working, they would become ‘habituated’ to a life without crime and vagrancy. Soon after its establishment Point Puer was producing junior shoemakers, tailors, sawyers, coopers, quarries, blacksmiths, boat builders, book binders and carpenters. All trades that would be in demand by the developing colonial economy.

In 1837 the barque Frances Charlotte brought boys to Van Diemen’s Land. They were all from poor backgrounds, uneducated, part of the residuum, or lowest strata of Victorian society. On the journey an attempt was made to train them in manual arts. Instead of learning bad habits from older inmates these young convicts would be taught skills that would aid both them and the colonial authorities during and after their term of incarceration.

Up to 20% of convicts arriving in Australia in the 1830s were boys aged 10–14. In Van Diemen’s Land, Lieutenant-Governors Arthur and Franklin and prison commandant Captain O’Hara Booth knew what would come from putting these boys with adult prisoners: apprentice criminals would become actual, gangs would form, power cliques, as well as the dreaded vice l’anglais (older and younger boys were separated at night in their Point Puer barracks). The reasoning was, anything a man could do, a boy could try.

In January 1834 the brig Tamar arrived from Hobart Town. Aboard were 21 adults and 68, mostly drunk, boys. Booth explained in his diary:

January 10: Tamar signalized – found on board an increase of 21 Adults and 68 Urchins – on the way down the latter evinced their dexterity by foraging out in the Hold of the Vessel a six dozen Case of Wine for me, had abstracted all but one Bottle – some of which they had handed in to the Adults – the consequences a scene of general intoxication – some of the Boys and Men brutal – landed all Men that were drunk and placed them in the quoad – rather disgusted …

It was obvious that men and boys had to be kept separate, at all costs. Horne explained that ‘boys and men are frequently out as absconders at the same time and may meet … Very lately, no fewer than 6 men and 10 boys were missing from the two places on the same evening.’

Point Puer’s first inmates arrived in December 1833 and started building their own accommodation. By the time of Horne’s visit, ten years later, there was a ‘Barrack’ for the now 716 boys, workshops, bakehouse, a building used as a school and chapel, and a gaol, consisting of three buildings, one being for ‘boys under sentence for faults’ and the other for those sentenced for more serious offences. The prison was run by officers, a ‘Catechist’ (who also ran the school), a Superintendent of the gaol, and various tradesmen, most of whom had been or were still prisoners or ‘Ticket of Leave’ men. This carried its own risk, although perhaps these men were determined to give the boys the sorts of opportunities they’d lacked.

Then again …

The 1840s saw the demise of transportation to Australia. New South Wales (then most of eastern Australia) stopped the practice in 1840 and convicts were diverted to Van Diemen’s Land. Public opinion here led to the formation of the Anti-Transportation League in the late 1840s and the last convict transport was sent from England in 1853. Four years earlier, in March 1849, the last 162 Point Puer boys were loaded onto a ship and sent to the Cascades in Hobart Town.

Walter Paisley had been released in 1838. Less than a year later he was arrested for housebreaking in Launceston. He was sentenced to transportation for life and sent to Port Arthur, across the bay from his old home. Here he was up on charges six times before being sent to the Colonial Hospital in Hobart in 1844.

Paisley’s life was typical of thousands. A society that had failed so many children had sought to deal with them in the harshest possible way. These early encounters between child and landscape, menacing convicts and ruthless authority were some of the starkest in the history of our fierce continent. Nightly, the Point Puer boys would have heard the Southern Ocean crashing on the cliffs beside their barracks. They might have thought of lost parents and siblings, friends, lives that seemed so distant they might have never happened. Benjamin Horne’s report to Sir John Franklin is full of statistics and opinions (‘…the criminal should not find that he has improved his condition by breaking the laws of God and man …’) But nowhere are the boys talked about as children. In a way, they had forfeited their childhoods.

Marcus Clarke knew he had the perfect setting for a novel about man versus nature. He describes the Tasman Peninsula as a ‘wild and terrible coastline, into whose bowels the ravenous sea had bored strange caverns, resonant with perpetual roar of tortured billows … Forrestier’s Peninsula was an almost impenetrable thicket, growing to the brink of a perpendicular cliff of basalt.’

The boys would have known there wasn’t much point attempting to escape. Some tried. Eleven-year-old William Bickle had his sentence extended by two years for insubordination and being ‘illegally at large.’ During his time at Point Puer he faced 65 charges, served 172 days in solitary confinement and suffered 300 lashes to his buttocks.

Today, Point Puer is gum trees and native grasses, the ruins of bread ovens and a few crumbling walls from workshops where boys carved stone for Port Arthur’s buildings. If you try you can hear Paisley singing inside his cell, the sound of twelve-year-olds reciting from their primers, perhaps even the sounds of happy voices playing in their hour off.

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

January 6, 2023

Patrick White's Lessons in Ham

This year marks the 121st birthday of Australia’s prodigal son: our best novelist, muckraker, playwright, dog breeder – you name it. I’ll try to avoid sycophancy, but Paddy White was the one who got me started. I read all of his novels and plays before I was twenty-five and, I suppose, his voice still resonates in mine, as it does in that of most Australian writers. White was our original and most unforgiving vivisector, holding a mirror to a country that didn’t want, or see the need, to look. He described himself as a monster, but that was because he could see the flaws in the glass, and was publicly willing to admit to them.

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

More than ever, this country needs a White. In a 1988 speech at Melbourne’s La Trobe University, he claimed that most Australian adults ‘remain children at heart’. He called them kidults. He said, ‘That’s why they’re so easily deceived by politicians, developers, organisers of festivals …’ And here’s the essence of why so many Australians have a problem with White: he sailed closer to the truth than anyone. He described an Australia that, for better or worse, still exists. ‘Australians have suffered in the past, which they tend to forget now that they’re on with the bonfires – the champagne (the ad man’s magic lure) and the festivals.’

White was constantly reminding us that we’re only as good as our worst off. ‘Aborigines may not be shot and poisoned as they were in the early days of colonisation, but there are subtler ways of disposing of them.’

For such an English Australian, he hated our subservience. ‘The Royal Goons will be with us most of the year [1988]. Queen Betty England is invited to open the ‘concept’ of Darling Harbour, and she and her bully boy will be at the inflated/ruinous Parliament House.’

Patrick White was born on 28 May 1912. Although his family were from the Upper Hunter Region (including his domineering mother, Ruth, who became Elizabeth Hunter in The Eye of the Storm), White’s family were in London when he was born. So much of how he wrote, and thought, came from a European perspective, but White’s greatest achievement was to tailor this view to an Australian landscape: Voss, trudging across the interior, ‘talking’ to his love, Laura Trevelyan; Ellen Roxburgh, with her fringe of leaves, and the escaped convict, Jack Chance, waking the sands of Fraser Island; and perhaps the best of all, for me, the Aboriginal artist, Alf Dubbo, and Holocaust survivor, Mordecai Himmelfarb, inhabiting the alleyways and factory yards of White’s mythical Sarsaparilla, riding their chariot towards salvation.

White was back in Australia as a six-month-old, becoming hard-wired to the sounds and smells of his native city on the harbour. At thirteen, he returned to England for secondary schooling at Cheltenham College, Gloucestershire, a period he later described as a ‘four year prison sentence’. He persuaded his parents to let him return to Australia where he spent two years working as a stockman at Bolaro, near the Snowy Mountains. But then he was back in England to study a BA at Cambridge, a period that resulted in his first novel, Happy Valley. This constant to-and-fro created a man who was part Rilke, part sheep-dip, part Camus, part Australian Suburban, bitches on heat, and backyard abortions. White’s enormous intellect, ear for dialogue, eye for character, would settle uneasily in 1950s Australia, after he returned to live in Sydney in 1948 with his partner Manoly Lascaris.

White’s connections with Adelaide, and South Australia, are many and varied. He was (almost) life-long friends with local author and historian Geoffrey Dutton and his wife, Nin (before the inevitable falling-out that befell most of White’s acquaintances). Like White, Dutton was born into pastoral wealth, this time in the Clare Valley, near Kapunda. ‘Anlaby’ (Australia’s oldest sheep stud) hosted White and Lascaris many times, as did the Dutton’s holiday house on Kangaroo Island. After White’s first visit to the island in 1962, Nin Dutton described how he would take hours cleaning the dishes: ‘All the knives were just so; all the plates rinsed three times.’ He and Lascaris would swim early in the morning and return to the Duttons’ house for a breakfast of fish and eggs. The Duttons forbade him to write on the island, and it’s here we can see a rare glimpse of our only (pre-Coetzee) Nobel Prize Winner for Literature with his guard down, socks off, itching, no doubt, to return to his writing desk in Sydney.

In 1959, White sent Dutton a play he’d written years earlier that had been sitting gathering dust in a drawer. Dutton told White The Ham Funeral should be performed at the Adelaide Festival. He presented the script to the festival’s committee who, at first, were enthusiastic. Artistic Director Professor John Bishop flew to Sydney to discuss the play with White. But, Adelaide being Adelaide, things soon turned pear-shaped for the playwright.

The Australian Ambassador to Washington was encouraging the committee to mount Archibald McLeish’s Broadway show, JB. Several of the governors just didn’t understand what White was on about in the Funeral. Local brewer Rolly Jacobs thought the script filthy (especially when the Young Man finds a foetus in a rubbish bin). Another two governors, Clive and Ewen Waterman (who owned, among other things, the local Mercedes Benz franchise) took advice from Glen McBride (an ex-Tivoli manager) who claimed the play was ‘not up to much’.

The play was then rejected because the governors, apparently, feared a poor box-office.

The committee became split between the pro- and anti-White factions. One pro- governor warned the others to ‘think seriously before turning down the opportunity of a world premiere of a work of this class’. But the nail was put in White’s coffin by an Englishman, Neil Hutchison, who’d been sent by the BBC to Australia to teach us a thing or two about culture (as Director of Drama and Features at the ABC). He told the committee that the Funeral would be ‘very tedious in production. There is practically no character development and the dialogue is insufferably mannered. As for the abortion in the dustbin … Really, words fail me!’

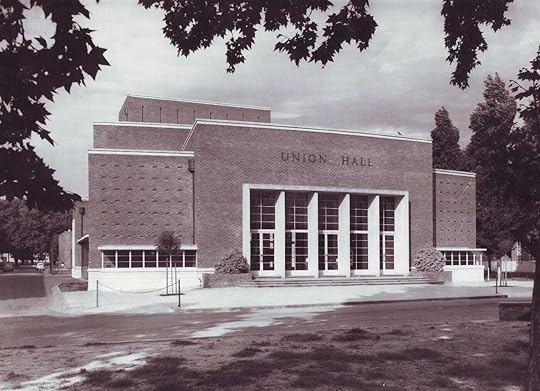

Luckily, Adelaide redeemed itself. The play was given to physicist-thespian Harry Medlin and produced by the Adelaide University Theatre Guild in Union Hall. Dutton and Max Harris got behind Medlin and supported the production. White was given a cheque for 25 pounds, and chose John Tasker to direct. On 15 November 1961, John Adams stepped on-stage as the Young Man. Joan Bruce, Hedley Cullen and Dennis Olsen all played a part in Australian theatrical history, the physical remains of which were lost when Union Hall was removed from the State Heritage Register by the incumbent anti-intellectual, anti-cultural Labor government. The theatre was then demolished in an act of cultural vandalism by the University of Adelaide in November 2010.

The Theatre Guild repeated its success (and affirmed its relationship with White) the following year by producing The Season at Sarsaparilla and, in March 1964, with Night on a Bald Mountain. By this time, the Festival had, according to David Marr, ‘relented sufficiently to list Night on a Bald Mountain among the fringe events of the fortnight.’ White, the Duttons and the Nolans (Sid was in town for a show of his African paintings) gathered at The South Australian Hotel on North Terrace. White stayed away from all writers’ events as they sounded ‘quite pathetic’. He wouldn’t have another play produced in Adelaide until March 1982, when Neil Armfield and the Lighthouse Company presented Signal Driver with a much younger John Wood and Kerry Walker.

It might be worth asking ourselves if all that much has changed since the days of The Ham Funeral and ‘the governors’; whether the Adelaide Festival is really interested in celebrating an indigenous culture, or just importing the best from other places. Are our festivals still chokers with modern equivalents of JB (which premiered in Union Hall on 17 March 1962)? What would White say? In reference to the 1988 Bicentenary celebrations he said: ‘When the tents are taken down, we’ll be left with the dark, the emptiness …’

Dutton and White parted ways in 1980. When White learnt that Dutton had accepted money from Mobil for a book he was writing (Impressions of Singapore, 1981) he told him: ‘Australia disgusts me more and more, but what really shatters me is when those I have loved and respected shed their principles along with the others.’

Dutton didn’t take it lying down. ‘It’s time you recovered your sense of proportion, your sense of humour and most of all your sense of humility…’ He told him to reread King Lear, so perhaps he wouldn’t ‘pontificate about other people’s lives.’

In the end, White set standards that no one (except perhaps Manoly) could reach. His life evolved into a set of theories and ideals that rarely connected with the real world of Australia in the 1970s and 80s. And yet, in the end, this is why we remember him as one of the Great Australians, along with some of his idols such as Chifley and Whitlam. After all, it’s not what one achieves in life, but what one aspires to. And it was this lack of ‘worthwhile’ aspiration that constantly disappointed him.

We still have so much to learn from the Whites of the world. He knew how easily decent people are led. ‘The masters will continue to hoodwink the more innocent by telling them they have the best economy, the tallest tower, the coziest casino, the greatest cricketer or swimmer.’

Sound familiar?

White and the 1973 Nobel Prize for Literature

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

August 18, 2022

The Naming of Plants

As you were named, you will know your world by names. People (Mum, for love), places (Woolworths, for food), ideas (spite, for Jacinta), dangers (‘Look Right Before Crossing’), pain (greenstick fracture, aged seven), hope (Mildred Wong, aged thirteen), nature (watching ants consume a chick that’s fallen from its nest). I never named a thing, but names just happened. Common, then scientific, as they thought it’d be smart to call (for example) the ponytail palm (which looks like an elephant’s foot) Beaucarne recurvata. But it is what it is, with or without a name. All things are. Unfortunately, the world you’ve been born into is all crash repairers and milkshakes, cars (and their many names) and fast food.

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Go into the world, the sun on your arms and face; squeeze into the gap between honeysuckle (Tecoma capensis) and fence; pull onion weed bulbs from the ground. Hide inside a golden diosma (Coleonema sp.), chaste bush, or hibiscus (one day you’ll pull one apart in a Science IIC to learn about anthers and filaments, stamens and petals). This will be your shelter, your hiding place, your observation post. Here, you’ll be able to watch the battle of man versus nature, the standardisation of unreliable ecologies, the making of things to be the same as other things. You’ll see your father mowing his soft-leaf buffalo, going up and down, then across, until the lawn is smooth (watch how he admires it), pleasant to the neighbours’ eyes. Then (perhaps another day) you’ll notice him on his knees forking dandelions (Taraxacum sp.), but he’ll miss one, and a week later you’ll find the seed head, pick it, blow the thousand seeds across his lawn. Just don’t let him see you doing it. He’ll mix poison and spray ryegrass, paspalam, marshmallow and lambs tongue, from the patchy couch on the nature strip. This grass (you’ll see) is different. Santa Ana. Drought tolerant (although he’ll water it every night with a sprinkler Jacinta will throw at you when you’re nine, splitting a lip, chipping a tooth). Santa Ana, with its religious connotations, because to your father, this is an ecstatic experience. One day, when a dog pisses on this lawn, your father will go out and say to the old woman: ‘That leaves patches, you know,’ and she’ll reply, ‘Well, don’t plant it.’ Then there’ll be muttered insults.

Another time, you’ll visit some distant cousin in a suburb that’s far older, more established, than yours. You’ll marvel at their lawn. You might, one day, come to know it as fescue. Tricky, thirsty, hard to maintain. And their garden will be different to yours. A sundial, perhaps, to link their world to the Greeks, or Romans (you’ll spend years studying these people, watching documentaries about their cypress-edged pools and villas). Rows of roses (Rosa – all different colours, no mould or yellowing or dead branches or spent flowers, because they have someone to take care of all this). Probably a date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) to invoke the tropics – a Canary Island if they’re especially well off. And that’s what you’ll learn. Some people have more money, a better car, more interesting holidays than you. You just sit all summer watching your father obsess over kikuyu.

Are you learning? Truth is, you’ll only remember the name of a thing if you need to, if it means something to you. Aboriginal people named what was good, but also, what could kill them. Staying alive. That’s another reason. For example, there beside the smoke tree, an oleander (Nerium oleander). Every kid you know will have one in his front yard. Because they’re unkillable, covered in year-round, pale pink flowers, blocking the view of your feral neighbour. You will be warned by your mother – don’t eat it, don’t lick it, don’t even touch it. Oleander, you’ll see, is the tree equivalent of the man on Tamsin Street who killed his wife. But eventually you’ll become curious, and pick a leaf, smell it, break it, see the white, milky sap, smear it on your fingers, run after Jacinta saying, ‘This stuff can kill you!’ Then she’ll tell your mum, and she’ll come out and shout at you and say, ‘What did I tell you?’ And hold your hand under the tap and rinse it off. All of this will happen, because you’re curious.

Curiosity is important. You won’t get far without it. This will happen, too. Jacinta will climb the jacaranda (J. mimosofolia) at the top of your drive. By that point, it’ll be so high the power lines run through it. She’ll stand on the top branch, inches from a thousand volts, and say, ‘It can’t kill you.’ You’ll realise what she’s about to do and say, ‘You’re nuts!’ You’ll see it all happening – you’ll see her zapped, thrown from the tree, neighbours coming over to try save her life. You’ll think, I’ll remember this, in sixty years – the day my stupid sister died. But then, she’ll reach out, touch the line, and laugh, and say, ‘It can’t hurt you unless you’re on the ground.’ And you’ll say, ‘But the jaca’s touching the ground.’ And she’ll say, ‘That’s different, stupid!’ And this curiosity will continue. Walking home, grabbing a handful of soursobs (Oxalis pes-caprae), tasting them, grimacing, spitting out the acid, as your sister laughs and says, ‘Dogs have pissed on them.’ And you: ‘Have not!’ Her: ‘You ate piss!’ Running home, down the drive, calling, ‘Mum, he ate piss!’ (And when you walk in, your mother saying, ‘Sometimes I wonder if you were born with a brain in your head’ – and you’ll think of telling her about the power line, but you won’t, because you would’ve learnt how many forms of torture a sister knows).

Some days will be like heaven (not that you’ll know at the time). You’ll wake to the smell of freshly-mown lawn, mock orange (Philadelphus sp. – growing all over the pittosporum that shades your room) coming in your window, the smell of stewing tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) drifting in from the kitchen. And you will know happiness. The feeling that, for the rest of your life, anchors you to the earth, gives you a reference point for how things should feel. You’ll get up, you’ll run outside (by now, this world will be important to you), watch your dad weeding (chickweed, nutgrass) around the few carrots (over-fertilised, and fading) and say, ‘What can I do?’ And he’ll say (and you’ll remember this, every word, when he’s gone), ‘Well, you could put these weeds in the incinerator.’ Your job. Done with care, because he’s trusted you (despite your mother, standing at the back door shouting for you to come inside for breakfast).

You will become confident in this world. Despite what I said at the beginning, you will have already learnt to make the most of every stem, every leaf, every fruit. Laid in bed listening to the bone-dry leaves of the ghost gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) moving against each other in a hot, summer northerly, and you would have seen the shadow of its branches (the street light behind it) across your bed at night. This intruder in your room, reaching out (but never holding) you. And you would’ve associated this with fear. That you were only partially safe (and your parents could only protect you so much). You would have heard of people falling from trees, dying of cancer, hit by cars. So maybe your mind would’ve turned to defence. Having a bulwark against the world that gaveth (you would’ve been sent to Sunday school by now) and taken away. Tedious words on a hot Sunday morning in a cold Baptist hall. So maybe you would’ve worked out that you could protect yourself by gathering a fistful of bottlebrush (Callistemon sp.) or callitris cones, and throwing them at your enemies.

You might learn that not everyone has been as fortunate as you. I’m talking about Mrs W., next door, her husband dead a few years after the birth of the boys. Single mum, struggling, no time to keep a well-clipped yard (despite your father offering to help). Mrs W., with her fifteen, twenty, unfixed cats rooting in her pissy-smelling rosemary when they’re in season. You’ll learn about life. You’ll discover litters behind the viburnum near the back fence. Or in the lattice of unpruned fig (when you went through the fence, explored her yard). Six, seven kittens, abandoned by their frisky mother. All rib, bone. You’ll tell your father, and he’ll blow his top, but he won’t say anything to Mrs W. because she’s had so much to cope with. But one time, you’ll find six dead kittens, and one nearly dead (gasping its last), and you’ll know what it is to be well-fed and loved. And (without telling anyone) you’ll dig a hole and bury them, even the one that’s still alive, and you’ll press down on the dirt to force the last bit of air from its lungs, because you’ll think that’s the kindest thing to do.

Mrs W.’s yard will be full of mint (Mentha sp.) that got away. It will signify (as you grow older) disease. Goosefoot, purslane, bindii (your father still on his knees) will be interruptions, endings. You’ll learn that weeds earn names like goat-head, devil’s face (three-corned jacks, always getting in tyres) because they’re untameable. But you’ll also learn that the world will provide for you. That for every dead almond tree (the skeletons in Mrs W.’s yard), your father has planted a dozen apricot trees, orange and lemon (the bells, words making songs), plum, peach and apple. You’ll learn that plants tell stories, and stand guard (every school with a pepper tree – no one knows who planted them, or why).

But here’s the problem. One day (aged thirteen or fourteen) you’ll come in from the garden, sit in your room, switch on the television, and forget. You’ll know the names of things, but you won’t understand them (or care). You’ll have become bored with the journey you started (what seems to be) so long ago. You will (I suspect) be happy to sit and listen to brighter, louder, flasher words for the world. So I hope (cos I can only tell you so much) you will remember what you’ve learnt. Not from me, but by yourself. Somewhere in there (I guess) is the world your ancestors inhabited. They’re trying to tell you something, but after so long, they can only speak in whispers.

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

July 4, 2022

Coming soon

This is Datsunland, a newsletter about Writing reduced for quick sale.

Stephen Orr's Blog

- Stephen Orr's profile

- 31 followers