Matador Network's Blog, page 1424

December 28, 2017

Mindful travel

If you have spent any time in therapy, or if you’ve read any self-help books in the last decade or so, you’ve probably come across the word “mindfulness.” It’s a fairly simple concept: basically, “mindfulness” is the practice of staying focused on the present moment. It’s useful in combating mental illnesses like anxiety, depression, or addiction because those illnesses are often fed by the mind’s tendency to fixate on problems or to unconsciously wander in the direction of worry and stress.

The concept is Buddhist in origin but has exploded in the past several decades because of its practical benefits. Too many of us are in the habit of letting life slip us by while we get lost in our heads, and mindfulness is an extraordinarily simple practice to keep ourselves focused on our actual lives and experiences.

2017 was a huge year for the travel industry — consumers these days often want “experiences, not things,” and that, combined with some pretty crazy cheap flights, has meant that more people are traveling than ever before. But choosing an experience over a thing can still be just another form of consumption. It can still leave you feeling unsatisfied and empty inside. As more people travel, more will realize — wherever you go, there you are. You can’t escape yourself. Which is why in the next few years, “mindful travel” will become a much bigger deal.

What would mindful travel look like?

When I was on my study abroad program, I took a poetry class. I am not a poet, but I figured that, since I wanted to be a writer, I should try things that were out of my comfort zone. Since we were abroad, our teacher suggested that the next time we were on a day trip somewhere, we should find a place that was quiet to sit with our notebooks, and then describe what we were feeling with all five senses.

The reason, he said, was that we could not write about an experience that we weren’t present during. He didn’t call what we were doing “mindfulness,” but that’s what it was — we simply had to take notice of what was happening around us by putting our full attention on the present moment.

My poetry, for the record, was still complete garbage. But my writing improved. Travel writing relies heavily on setting, and I hadn’t realized until then just how little I focused on the world around me when I went somewhere. I was more often concerned with what I was going to do next, with whether I was having a good enough time, or with whether the cab driver was trying to scam me. The sensory practice forced me to put a stop to all that.

I don’t write poetry anymore, but I’ve remembered the lesson about the senses and, when I go someplace new, I try to notice what my senses are picking up on, what I’m feeling, and what’s going on around me. It has made travel much more memorable and enjoyable.

Why do we need mindful travel?

Many people of my generation (the dreaded millennials) have grown up seeing that materialism has not helped our parents’ generation in living happier, more fulfilled lives. There is no point at which a materialist ever has enough. And so, when I left home, I decided that my life wasn’t going to be spent acquiring things, but that, instead, it was going to be spent acquiring experiences. This, I figured, would make me a happier, more fulfilled person.

But that didn’t pan out. Travel did not solve all of my problems. If I didn’t like who I was, and then decided to go to a new country to try and chase away that feeling, I would quickly find that I was still the same person I didn’t like, only in a new setting.

What I hadn’t realized, as a young man, was that acquiring experiences instead of things was still a form of empty consumerism. I could go to all 200+ countries and still hate myself, just as I could make a billion dollars and still hate myself. When you eat a sandwich, it doesn’t mean you’ll never be hungry again, and when you do something that makes you happy, it does not mean that happiness will be staying permanently.

When we watched our parents growing up, we saw that new shiny things did not fix our parents, and when our kids watch us, they will see that visiting new exotic places did not fix us. At that point, they’ll have to ask themselves — is it possible that the problem it isn’t with what we’re consuming, but with consumption itself?

Mindfulness is the healthiest way out of that trap. It emphasizes non-attachment, and it does not put a premium on some emotions (like happiness) over others (like sadness). Travel will still be a part of mindful lives, but it will be slower, more thoughtful, and more fully lived. If we want to break the cycle, then mindful travel is the future.

More like this: How to slow travel in a fast-paced world

Don't move to Denver

Tucked in the back of any Denver local’s mind is a collection of justifications. For the reasons why we live here, why we’re hesitant to move away, and how we knew that this city was badass long before the stoners, hipsters, and aerospace engineers came in and told us so.

But today we’re not talking about those things. They can stay buried in the back of our minds until we’re two or three pints of Yeti down and some unwitting tourist on the next barstool won’t stop prying. The focus here is on why, for the love of god, you SHOULDN’T move to Denver.

1. You have to learn the neighborhood streets to get around town efficiently.

I-25 is a nightmare. Ever since CDOT finished the construction at 6th Ave, I can’t even make the last-second call to bail on 25, stay on 6th to Broadway, and avoid the cluster when heading east into town. Instead, one must learn the less-traveled routes. This takes time and effort and often involves becoming acquainted with the city’s unique neighborhoods and what they have to offer.

2. You may develop a burning passion for waking up very early.

Trailhead parking lots are increasingly crowded, but it’s all good because the trail is always more beautiful when you beat everyone up anyway. Same goes in winter, unless you’re smart and buy a Loveland pass. And those powder lines don’t stick around all day!

3. You’ll become overconfident in your right to brag about where you live.

It happens. Especially when traveling abroad, because the fact that more and more people know where Denver is further confirms my belief that our city isn’t the B-rate Cowtown that east coasters used to label it as back in the day.

4. Unless you’re in a mountain town.

Even though the residents of mountain towns typically moved there from either Boston or a flyover town in the Midwest, for some reason they feel justified to turn up their nose to people from Denver. As ridiculous as it is, you’ll have to get comfortable saying “the front range” or else develop a follow-up like “but we’re actually out in Green Mountain on the western edge, so not technically Denver.” This steals the upper hand right back, as it immediately becomes apparent that the Masshole you’re riding up the lift with doesn’t actually know anything about Colorado.

5. Your sunscreen costs will go through the roof.

The cost of sunscreen just keeps going up, and we’re feeling it here. All those bluebird days beg me outside, where it immediately becomes apparent that another slathering of the ole’ Banana Boat is in order. It’s getting so bad that soon I may have to dip into my craft beer budget in order to foot the bill, dammit.

6. It’s hard to catch a break.

For real. I often find myself planning to head home after a quick morning hike and get some work done on a story, but get diverted by the undying urge to go just a little deeper on the trail. Next thing I know, I’m scrambling back to the parking lot at 2 PM and feel that the only appropriate way to call it a day is to stop by that new brewery that just opened in the old mechanic shop by my house. This, of course, leads to bar chatter and an invite to go see The Yawpers play at Hi-Dive, and before I know it, it’s last call and all I’ve done is have the best day of the month.

7. Friends and family will never stop visiting you.

Better get that futon ready, because it’s amazing how often people you know “just happen to be coming through town!” It’s great to host those you love. Conferences, ski vacations, road trip pass-thrus, you name it. It’s crazy how much is going on here these days!

More like this: 11 things you’ll only understand if you’ve been to Denver

Impromptu trip to Montenegro

Towards the tail end of an epic 3,300-mile rail journey across Europe, during which I’d haphazardly crisscrossed the continent in a generally southeasterly direction from Paris, I realized that Dubrovnik, where I was currently sitting beneath a blooming bougainvillea overlooking the rooftops of the fortified town, was just a short bus ride away from the capital of Montenegro.

I’d heard nothing of the destination, but a quick Google showed a number of those “Best of” and “Undiscovered Gem” awards from travel guides across the spectrum. Usually, this is a reason to avoid a city, but it was the offseason, and I learned there was a train ride between Montenegro and Serbia that those in the know claimed was the best on the continent. So early the next morning, I scooped up my backpack, exited through the city gates of Dubrovnik, and boarded a rickety bus that was to trace a thin sliver of land south between towering peaks and the shimmering Adriatic.

What I found in Montenegro fascinated, confused, frustrated — and, at least once, terrified — me enough to cement it as one of my favorite countries on the continent.

1

Kotor

On the first afternoon in Kotor, a torrential storm dumped so much water on the small town and its surrounding mountains that a knee-deep river flowed past my Old Town apartment. The weather forecast predicted much of the same for the next day, with just a short window of sunshine in the morning. And so I rose early the next morning, determined to conquer the town’s most popular attraction - the vast walls and ancient fortress stretching into the mountains above the city that date back to Illyrian times.

2

Kotor fortifications

These days, the fortifications serve little practical purpose, but the crumbling bricks and sheer switchback pathways feel authentic and unspoiled. At times, they appear to blend in with the cliffs on which they’re built. But they also elevate you to a remarkable vantage point above the town, where you’re treated to panoramic views of the uniform rooftops, scuttling tourists, arriving cruise ships, and the fjord-like bay that they sail.

3

Top of the fortifications

Towards the top of the fortifications, a rumble of thunder sounded out from the mountains above. Almost simultaneously, the skies darkened and heavy raindrops began to thud into the earth at my feet. A once-listless Montenegrin flag fluttered slowly to life in the growing breeze. I looked down towards the town, now miniaturized by my altitude, and realized my only option was to hunker down in the dilapidated fortress and hope for the storm to pass. After 30 minutes of increasingly ferocious rain, I realized this was unlikely, and so I waded down the near vertical staircase in ankle deep water, ducking lightning bolts and cursing the fact that I didn’t take the receptionist’s advice: “Don’t ever trust a weather report in Kotor.”

Intermission

Trip Planning

35 of the world’s best places to travel in 2017

Matador Team

Trip Planning

7+ under the radar destinations for cruises

Matador Staff

Galleries

Think Seattle is grey in the winter? Think again.

Sigma Sreedharan

4

Perast

I spent much of the next morning drying my clothes with a small hairdryer I found in the apartment cupboard. But then the skies cleared once again, and I boarded a bus to the nearby town of Perast. This beautiful, tiny old town that looks like a missing piece of a Venetian puzzle sits on an idyllic stretch of the bay and offers easy access to two intriguing islands just a short boat ride away.

5

Boats to the island

Boats potter across the bay to Our Lady of the Rocks, an artificial islet steeped in mystery and legend, and home to a small Venetian-style church. From the road, it looks like it broke off from the mainland and floated into the center of the bay, and legend has it that the island is built upon ships sunk with stones to form a solid foundation. But it’s the boat ride to and from the island, costing just a handful of coins and taking only a few minutes, that offers the most dramatic views of the surrounds.

6

Hike to Fort Vrmac

On my last evening in Kotor, I stumbled across a nugget of information that would result in one of my most memorable experiences of the last two months of travel. Apparently, one of the best preserved and abandoned Austro-Hungarian-era military bases on the continent sat on the hills above the town. The hotel receptionist’s eyes lit up when I asked him about the base. “You’re not supposed to enter,” he said. “I nearly died in there when I fell through a hole in the ground. But I’ll tell you the best way in. First,” he continued, pulling out a map, “you’ll need to hike this path on the other side of the town...” At sunrise the next morning, I set off and walked the steep switchback pathway through dappled sunlight with ever-changing views of the town and mountains on the opposite side until eventually, I reached the quiet and abandoned site.

7

Inside Fort Vrmac

When I reached the silent summit I soon found what I was looking for - the hulking concrete mass of the military base, and the small window to enter it. I lifted myself up and onto the small stone windowsill and pressed my face into the darkness. Deep inside the base, I heard an ominous and repetitive drop of water echoing off the cavernous interior. I wanted nothing more than to turn back, but instead reached into my pocket, activated the torch on my phone, and dropped down into the interior of the military base.

8

Exploring the fort

Almost immediately, I realized my phone torch was of little use, but I pushed on gingerly across the crunching gravel and through the labyrinthine network of tunnels, passageways, and up concrete staircases. As I walked in total silence through the base, the sound of the dripping grew louder, and I ducked large bats flapping towards down the dingy corridors and stepped around potentially deadly holes in the ground. I walked up flights of stairs into total darkness and found rusted casemates, motor turrets, and row upon row of eerily abandoned rooms lined with rusted hooks until eventually, more than an hour later, I realized that if I didn’t retrace my steps carefully, I may just get lost in this terrifying world.

9

Budva

It would be easy to paint this town as a beautiful beach resort set on the shimmering Adriatic. But the reality, at least in the offseason, was anything but glamorous. Stray dogs and cats picked through litter on the stony beach as they walked between dilapidated beach bars. Rusted and crumbling jetties stretched out into the ocean. In the distance, a closed bungee-jump crane and platform stuck up into the hazy early morning sky, and a neglected mobile booth with ripped curtains and a hand-painted sign reading “Massage” hanging off-center made it feel as if I’d woken up to a nuclear disaster. Reviews and a row of luxury yachts close to the old town suggested that it may get a clean sweep for the arrival of rich foreign tourists in summer. But in mid-October, I was more than happy to bid this bizarre beach village goodbye after two long nights.

10

Train to Serbia

A week after arriving in Montenegro, I boarded my train in the small coastal town of Bar and headed for the Serbian capital of Belgrade. I’d read that this was the most dramatic train ride in Europe, and after gaining elevation on the slopes of the Montenegrin mountains just a few minutes into the journey, I realized that the claims were likely to be true. Large trucks on the road many hundreds of meters below provided some sense of scale to this engineering feat that once ran Tito’s famous Blue Train, but it was when we burst through a tunnel into one of the most incredible autumnal displays imaginable that I realized this was indeed the best train ride on the continent.

11

Autumn in Montenegro

As the train journey progressed through the autumnal wonderland I didn’t want it to end. Several hours later, and at least two hours behind schedule, the scenery outside darkened and the no-frills carriages lost their appeal. But sitting in the unlit carriage with a handful of commuters allowed me the opportunity to reflect on a short but fascinating journey into this beautiful country.

More like this: I just traveled 3,300 miles through Europe. These were my favorite moments.

Third stage of grief in Jamaica

The craft market, under a blue tarp at the back of the produce market, was easy to miss because, like everything else in Jamaica, there was no sign. An old woman with blurry eyes and cropped white hair sat behind a table that was scattered with refrigerator magnets, shot glasses, key chains, and Rasta hats — red, yellow, and green. She waved her hand over her wares like a magician and then called to me, asking, “Are you a travel agent?”

I laughed. “No, do I look like one?”

She folded her hands over her belly and said, “I’ve been watching you and was admiring the way you wrote notes.” She pointed to the journal in my hands. “You need another pen?’ she showed me the pens on her table.

“I’m not a travel agent,” I said. “I’m a writer. Or at least trying to be.”

“Oh,” she nodded, “then you do need a pen!”

“I have a pen.”

Then she nodded and said, “But you look like a travel agent.”

“Thanks,” I said because looking like a travel agent seemed like a compliment, though I couldn’t say why. I knew, though, I was really just another tourist, someone who might spend a few dollars on a Rasta pen or Bob Marley shot glass.

I introduced myself, and she told me she was Kathleen Henry. “Nice to meet you,” I said, and we shook hands. She told me that she was 78 years old and that her photograph was in the Norman Manley International Airport in Kingston. Because she was trying so hard to sell her items, I asked her if she was paid for the photograph. She shook her head, and I said, “Selling the rights to your image might make you a lot more money than selling your wares.”

I could tell that she wondered if maybe she ought to have been paid. I hadn’t meant to upset her, so I told her that when I left Kingston, I would look for her photograph. She smiled.

I was traveling to Jamaica for work, teaching a travel writing class. I had taken my students on a field trip to the town of Port Antonio and given them a scavenger hunt of activities designed to help them get a story. I suggested they walk around alone. None of them did this — choosing instead to explore the town in small groups — except for me. I wanted to be on my own, but I was too distracted to do their assignment myself. I mostly just wandered around, trying to pay attention to things — stray dogs following a man who fed them, the smell of jerk chicken, the vendors selling sugar cane or coconuts that they would retrieve by climbing into the trees.

I also wanted to bring a gift home from Jamaica for my mother, something useful. We were between chemotherapy treatments. She had been given three months to live back in October. Now it was January.

I fingered a green, yellow, and red knit cap. “Rasta colors,” Kathleen said. “Fifteen dollars.”

I nodded and then said, “My mom is 78, too. I’m thinking of buying this hat for her.”

“Ten,” she said.

And I hadn’t meant to, but I told Kathleen that I wanted the hat because my mother no longer had her hair. When she looked at me in a strange way, my voice turned to scratch and squeak, but I managed to say, “Because chemotherapy.”

I wanted to tell Kathleen that I didn’t want to bargain, that that wasn’t why I was telling her this, but saying so would have sent me into full cry. So I just put the hat back on the table.

Kathleen Henry took a long look at me, and all I could offer her was a weak smile, and I said, “I’m sorry.”

The way she looked at me, I believed that she really saw me, or maybe it was just that caught in her gaze, I finally saw myself, and the reckoning of my grief. I started to cry, wiping the tears away with the back of my hand as soon as they came. I apologized again, but she looked at me in that way that said it was okay. I hoped my students wouldn’t wander into the market then, see their teacher there, crying.

Kathleen put the hat in a plastic bag, looked around so nobody would see, and handed me the bag.

I pulled out my money, and she looked at it. I didn’t want the hat for free. I didn’t want to cry. I didn’t know what to do. I held three fives, and Kathleen Harris took one of them and said, “I hope your mother gets better” and then “I’m very sorry.”

I walked out from the dark canopy and into the light, no longer just a tourist, but a woman who was losing her mother.

More like this: When travel can’t cure grief

Trips to take in 2018

2017 was the year of traveling fearlessly. In a world so often portrayed as risky, dangerous, the reality is that when you actually get out there, you realize how little truth is in those fears.

Looking ahead, 2018 is about traveling deeper. It’s about appreciating what we have both here in the US and around the world.

2018 also marks the 50th anniversary of the US National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act, which gives special wilderness protection to designated rivers and lands around the US. In honor of this, we’ve highlighted several public lands — national parks, forests, and recreation areas — that can make trips extra special, and can be found even in the middle of large metro areas.

Wherever you find yourself in 2018, here’s to traveling deeply, and making your best travel stories yet.

1. Nevada Wild West towns road trip

Dark skies, ghost towns, and cowboy poetry

Photo: BLM Nevada

People always associate Nevada with Vegas, but what really deserves checking out are the many cool small towns. An interesting fact as well: Nevada has the most hot springs of any state in the US. For 2018, we’re recommending a cowboy town/ghost town road trip with little side visits to some amazing national parks and public lands. Start in Reno, a kickass little city in its own right (with the Truckee River whitewater course flowing right through), and then head out to Virginia City and across Hwy 50 for some incredible open space before hitting up Ely and Great Basin National Park. From here, you’ve got a ton of options looping back north or south; check our Nevada small town guide.

When to go: Spring or fall if you want to avoid extreme desert heat; this can be a great winter trip. In Elko, the 34th National Cowboy Poetry Gathering is taking place January 29 – February 3, 2018.

Get deeper: Great Basin National Park is one of the last places left in the US with almost no light pollution, and is designated an International Dark Sky Park. Throughout the year there are free astronomy programs with telescope viewing and talks from rangers.

December 27, 2017

New Year traditions around the world

We’re about to say goodbye to 2017 and welcome 2018. Do you have your New Year resolutions ready? Did you manage to keep any of those promises you made to yourself a year ago? Did you go to the gym, quit smoking, and travel a bit more? If you didn’t, don’t worry. 2018 will be different, right?

But how can you make sure this will be your year? Here’s an idea — do something different to celebrate those last and first days of the year. You can find inspiration on this infographic by PackSend with 50 New Year traditions from around the world. Will you eat 12 grapes? Hang an onion on the front door of your house? Throw white flowers into the ocean? Try talking to a cow? If you start the year doing some of these things, 2018 will definitely rock.

Hilarious in China

On a recent trip to China, from Beijing in the north, to the province of Yunnan in the southwest, to Shanghai in the east, I had people howling. The only problem is, I was rarely sure why.

My Chinese is, to use the local expression, mamahuhu (literally meaning horse-horse-tiger-tiger but colloquially implying something is just so-so). But it gets me by. And often in China, I think that locals hearing a white dude uttering something close to Mandarin is unique enough to elicit a favorable, often humorous response. Comedy is, after all, in large part about defying expectations.

Usually, when I got the laughs, I wasn’t necessarily trying to be funny so much as friendly and engaging. My goal was a connection with people, not an ovation. Humor, however, turns out to be a universal door opener even if it must be contextualized for each culture.

What follows are some examples of what made people laugh in China on this trip with my son, a recent college grad. As you’ll see, some aren’t exactly knee-slappers but for some reason, they worked. Obviously, knowing at least some of the local language helped. But I think the main secret is this: be respectful, be curious and be kind. But then, just have fun. You never know the response you might get…

Try a little self-deprecation.

On our first morning in China, my son and I went to Beijing’s Lama Temple. At the entrance, a woman was handing out boxes of incense sticks. “Are they free?”, I inquired. She nodded. I then asked, “Could I get one for my son as well?” I pointed to him. “Your son?” she said, lighting up. “I thought he was your younger brother!” “Really? You’re too kind,” I responded then added, “I should get you to tell that to my wife so she’ll appreciate me more.” For some reason, the line worked. The woman howled. And so began my confused relationship with Chinese humor. Sure, I was glad she found it funny. But it wasn’t that funny. Or so I thought. Until I used it again and again on our trip with the same results.

Brush up on your zodiac humor.

Whenever the age issue came up later, I noticed something curious. People rarely asked my age. Instead, they wanted to know what year both my son and I were born. Age didn’t matter, but our Chinese Zodiac year did. Each year has an associated animal. In Lijiang, China, a college-aged woman was helping us at a store. She discovered that she was only two years younger than my 23-year-old son. She was a rat and, doing the math, that made him a dog. I informed her I was born in the year of the ox. So later, when a small mutt came up and stood beside her and my son, I said, “Oh look! A rat between two dogs!” Big laughs. A few minutes later, she showed us her pet kitten. “How is that possible?” I asked in mock seriousness. “I didn’t think rats got along with cats.” This time, not even the hint of a smile. “I’m not a real rat,” she said. Hmmm.

Tread lightly around politics.

In the midst of Lijiang’s daily market, I chatted with three lovely old Naxi women. After the usual “Where are you from and is this your brother?” comments, the lead talker asked me what I thought about America’s president. “Aiya!” was all I could say. It’s China’s go-to expression that can be applied to almost any situation from, “Aiya! The plumbing is backed up!” to “Aiya! You’re not wearing that to my parents’ house for dinner, are you?” In this case, it was an effort to deflect a political conversation. China is, after all, despite the free-wheeling capitalism all around us, a communist country where politics is not a subject you want to pursue. My “Aiya!” response elicited smiles all around. But it only provoked my inquisitor to go further. “China and America are like one big family. Oh Ba Ma understood this. But your current president…” She then took her weathered pinkie, held it up, and waved it in the air. Then, her two missing front teeth aiding her, she spat vehemently on her pinkie. Well. I guess we all understood how she felt about Trump.

Throw in some quirky sayings.

Another way to get laughs was to employ some Chinese idioms people don’t expect foreigners to know. For example, at one point my son went to buy some water. He came out of the store asking for an additional kuai (the term for the local currency). I asked how much the water was. “Six kuai” he said. “That’s crazy. They must be gouging you out here in this park.” This was all in English. He then pointed out that the six kuai was for two bottles, not just one. I turned to the woman selling the water and explained in Chinese, “I thought he had said it was six kuai for one bottle, not two. If it had been for one I would have assumed that you were ‘hanging a sheep head but selling dog meat.’” This is an idiom used to refer to someone cheating you. She took no offense. Instead, she literally bent over laughing. I think it was like hearing a three-year-old spout some witticism from Oscar Wilde. The words and the speaker didn’t line up.

Play with your food.

Another place I routinely used idioms was over food. Many Chinese people marveled that Westerners like us could use chopsticks. And they didn’t hesitate to tell us. I can’t imagine going up to a Chinese person in a restaurant here in the US and saying, “Wow! Amazing! You can use a fork!” But such was the case there. When locals made the inevitable comment about using chopsticks, I threw out this old tried and true expression: “When eating Chinese food, if you don’t use chopsticks, the food doesn’t taste good.” Guaranteed amusement.

Observe and comment.

You don’t have to say much to get a laugh. In this case, along one of the narrow streets of Shaxi, China, I simply said, “Very useful” and pointed to the dog carrying the hat. That’s all it took to get a good round of laughter.

Get a running start.

In the small, ancient water town of Tongli near Suzhou, my son and I dined at a table along one of the canals. After dinner, as I was paying the bill, I said hello to the people at the table next to ours. “You ordered two bottles of beer!” one of them said. I wasn’t sure if he was amused, shocked, or proud of our beverage choice. But I looked down on their table and saw a bottle of Bai Jiu (white liquor that can remove fingernail polish, stomach linings, or driveway stains). I told them, “Oh, you’re drinking Bai Jiu!” They beamed and held up the bottle. “We just drank beer,” I said then added, “I guess this must be the adult table where you get to drink Bai Jiu and we were at the kids’ table drinking beer.” All four of them started laughing hysterically. At first, I wondered why my comment was so funny. Then I looked back at the bottle and realized it was half empty. Anything is funnier when you’ve consumed that much Bai Jiu.

Work the material that works.

One sure-fire laugh-getter was the phrase, “Hao de bu de liao.” As near as I can figure, it translates to something like, “Super-duper.” It sounds funny when you say it. The meaning is funny. And when you use it in odd situations, it always gets a laugh. “That meal was super-duper!” “The weather today is super-duper!” “Do you need another napkin?” “That would be super-duper!” Laughs every time.

It’s not the jokes that matter.

By the end of the trip, I was never really sure why people were laughing the way they did. But it didn’t matter. We made wonderful connections with the people we met. I may not have understood the nuances of Chinese humor, but I could always tell when something clicked, when I went from being just another foreign traveler to someone they seemed genuinely glad to have met. Laughing together fosters key moments of openness and connection. And those moments don’t make your trip just fun or interesting. They make it super-duper.

All photos are the author’s.

More like this: 10 things the world can learn from China

Don't boycott travel to Myanmar

Myanmar, formerly Burma, has become a bucket-list destination for travelers visiting Southeast Asia. Pagodas, untouched nature, and welcoming locals lure visitors to the less-traveled ASEAN nation that is home to 135 recognized ethnic tribes — a statistic that excludes the Rohingya.

Demands for a travel boycott of Myanmar have launched in response to international condemnation and media coverage of the Rohingya tragedy. Travelers are pressured to consider whether they’re morally endorsing the Burmese military’s inhumane crimes against the Rohingya by visiting Myanmar. Boycotting may seem like the honorable thing to do, as no one wants to be complacent of human suffering, but the reality is that a sanction against Myanmar isn’t noble and won’t positively impact the humanitarian crisis. Here’s why:

Understanding the Rohingya exodus.

The Rohingya are a Muslim community that has resided in the Rakhine state of northern Myanmar for centuries and continually faced discrimination and brutality. This has resulted in a mass exodus — an estimated one million Rohingya refugees have fled Myanmar. The mistreatment of Rohingya was labeled “ethnic cleansing” in 2013 by the Human Rights Watch. The United Nations reflects similar views and has labeled the Rohingya as the most persecuted minority on earth. Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, described the situation as a textbook case of ethnic cleansing.

The world has been paying attention to the development of the ethnic persecution of Rohingya after an incident on August 25th. The Burmese government claims that security outposts were attacked by the Rohingya militant group Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) which is recognized as a terrorist organization. Since then, the Burmese military has been actively eradicating Myanmar of the Rohingya.

Violence towards the Rohingya existed long before the current global concern of genocide. Some trace the conflict back to World War II when Rohingya fought along the British and Rakhine Buddhists supported the occupying Japanese. Myanmar was previously under military domination for 50 years during which Rohingya were not permitted to leave the Northern Rakhine State, and other Burmese were not allowed to enter the region. Rohingya have been denied basic human rights including higher education and health care for decades. They were previously required to commit to not having more than two offspring.

Members of the Rohingya society have been denied citizenship in Myanmar since the 1974 Emergency Immigration Act and again in 1982 under the Burmese Citizen Law which reinforced the governing military’s stance that Rohingya are unwelcomed illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. Rohingya are entirely stateless and do not even exist according to Burmese rhetoric. The term Rohingya alone recognizes that they are a minority group and thus the phrase is hardly used in Myanmar. Instead, many Burmese refer to the group by what is known as a derogatory racial slur in Myanmar: “Bengali”.

The hate towards the Rohingya has been positioned by international media as a Muslim vs. Buddhism agenda adding to increasing global Islamophobia. The issues go beyond religion — it is rooted in citizenship rights such as government support, education, and job opportunities. Many Muslim Burmese live in peace in major cities such as Yangon and Mandalay where there are many Islamic communities.

Doctors Without Borders conducted a field survey and found that, at minimum, 6,700 Rohingya Muslims were murdered by Burmese security forces during the eruption of violence last August and September. In contrast, the Burmese Office of the State Counsellor claims the death toll is closer to 432. It’s difficult to verify the narrative, tally the dead, or gauge the damage, as both journalist and aid workers are banned from entering the area.

The information reported by trusted news outlets has been gathered from satellite imagery and interviews with Rohingya who have survived the dangerous journey to the refugee camps in Bangladesh. Entire communities have lost their homes, livestock, and fields of produce due to fires started by the military. Extradited Rohingya have reported that Burmese military members have gang-raped women and savagely murdered children. According to the Burmese forces, the recent offensive against Rohingya is meant to target terrorism, but most victims from the ongoing massacres have been unarmed villagers, not Rohingya insurgents. Burmese officials continuously claim that these stories are exaggerated.

Do travel boycotts lead to change?

Considering that the systematic violence towards Rohingya has been happening for the better part of 50 years, the simple answer is no. Although there was never an official ban on travelers entering Myanmar, pressure from Western governments urged travelers to avoid visiting the country. During this time of minimal tourism in the nation, horrific war crimes continued to occur. The unofficial travel boycott didn’t affect the Burmese military or change their attitude towards Rohingya.

A travel boycott won’t encourage the militia to stop the pogrom of Rohingya. The conflict has been ongoing for decades and is gaining more attention in part thanks to foreign visitors raising awareness and media meeting demands for information about the Rohingya. This exposure of the horrid actions of the military would not have happened, nor will it continue to happen, should Myanmar be sanctioned by foreign nations.

A travel boycott would further endanger the Rohingya. By isolating the country, the military would be able to discreetly continue to cleanse Myanmar of Rohingya without being held accountable. A travel boycott would eradicate the progress being made towards exposing the actions of the Burmese junta. The Burmese people are also not a reflection of their military. It would be Burmese civilians, not the military, that are the collateral damage of a travel boycott.

A decline in tourism simply won’t change the Rohingya emergency but could severely worsen the situation. “A tourism boycott wouldn’t help the Rohingya as it may antagonize some of the hardliner bigots even more,” says Yin Myo Su, Founder of the Inle Heritage Foundation. A panacea must be reached but a tourist boycott would provide no aid to the Rohingya. It would be dangerous and catalyze blaming Rohingya for a drop of tourism in Myanmar.

Burmese-American and frequent traveler Mary Marston shares that, “a travel boycott may make the person or group instating it look good, but it’s not really helping anyone but their own moral compasses.” To boycott is a sign of extreme privilege. Travelers may elect to spend their tourism dollars in another country, but the locals that rely on foreign spending for their income won’t easily find other opportunities to earn a living in nations plagued with poverty.

Mi Mi Soe, a local guide for Sa Ba Street Food Tours, explains that “Myanmar has only recently opened up to the world after decades of the people being closed off. It is important that we find our place alongside the rest of the world and try to find solutions together, rather than push each other away again. Not every person in the country is involved or kept up-to-date on the conflict, many ordinary people do not want to see pain between any race or religion. ”

Tourism doesn’t fund the military brutality.

The government and military are not the same entity in Myanmar. They operate separately with the military widely influencing the democratic government. The constitution was drafted by the military in 2008 and did not give the government control of the army. Instead, the military holds power over the police, border patrol, security services and 25% of parliament.

Today, the majority of people working in tourism in Myanmar are operating private businesses. Previously, the military dominated the tourism sector and owned the majority of hotels and transportation operators. To be a responsible traveler, think twice before buying a data sim card from state-owned MPT. Don’t stay at hotels believed to be affiliated with the regime such as The Strand, Chatrium, Inya Lake Hotel, Naypyidaw’s Lake Garden Hotel, Panorama Hotel, Aureum Palace Hotels, Hotel Max, and Royal Kumudra Hotel, to name a few. Avoid flying with state-owned Myanmar National Airlines (MNA) as well as Bagan Airways or Yangon Airways which are on the US Treasury blacklist. Don’t visit the Mandalay Palace which is a newly active military base without much historic importance.

It’s inevitable that the government will benefit from visa fees, which are US$50 for most nationalities for a 28-day visa, entry fees to Bagan (US$18.25 for a 5-day permit), Inle Lake (US$10 for a 5-day permit), and tax revenue from purchases. But the government is not the military and the revenue from these fees and taxes support government programs that organize public healthcare and education.

Tourism funds locals whose livelihood depends on travelers.

The tourism industry in Myanmar is nascent. Although the borders in Myanmar were never closed to foreign visitors, tourism has only spiked in recent years. Soe says that “over the last 5 years, tourism has been a very positive force, creating many jobs and opportunities that never previously existed in our communities. I work as a street food tour guide and this type of job never existed before tourists started visiting and wanted to discover our local food. On our tours, we visit family-run places to be sure that all of the money is being spent responsibly at a local level.”

Tourism is vital to the local economy in Myanmar, especially among the lower class. Marston has seen this first-hand, “tourism is helping alleviate poverty in Myanmar by creating new jobs in tourism, hospitality, and infrastructure-related industries because of the need to accommodate tourists.” The Oxford Business Group reports that employment from tourism in Myanmar will rise by 66% between 2015 and 2026. The potential for tourism to impact the country is immense.

Many locals who live under the international poverty line have the opportunity to benefit from tourism-related income. Su reflects that “Community-based tourism in villages can provide not only support for the community, but it can bring meaningful encounters between guests and hosts, and it can increase local’s pride in traditions and revive culture.”

Traveling responsibly in Myanmar, or any nation, puts money directly into local hands. From booking privately-owned transportation, staying at guesthouses, eating at hole-in-the-wall establishments, hiring self-employed guides at heritage sites, and purchasing souvenirs from artisans are just a few ways travelers can support local communities directly. Not only are these travel choices ethical, they’re typically more affordable.

Sammy Grill, General Manager for Intrepid Travel in Myanmar shares, that “there have been company-wide debates at Intrepid on whether to visit Myanmar. The majority decision is that we do not boycott destinations for ethical reasons, but instead we make sure that our trips include as many local experiences as we can. That’s how we can introduce both travelers and locals to different views and cultures.”

Visiting Myanmar does not normalize the plight of the Rohingya.

As travelers, we may engage in meaningful dialogue with locals. Su wants international travelers to “interact with young people, help with their language training, learn about the character of Myanmar’s unique ethnic groups. Visitors can help locals learn more about the world outside of Myanmar, inspiring them to reach beyond the circumstances that have confined them in the past.” Travelers can be a part of a paradigm shift by sharing their educated stance on human rights, exploitation, and violence. When appropriate, disseminate facts and encourage locals to think for themselves in order to come to their own conclusions. Some Burmese fear the military and believe that discussing politics can be dangerous in public — only initiate conversations in a private setting and never impose your own emotionally-driven views.

Su encourages travelers “to apply the same moral lens when speaking of other tourist destinations. Don’t practice selective moralization with Myanmar and not with others.” Boycotting tourism in controversial destinations does more harm than good. Continued tourism in Myanmar will keep the global spotlight on the Rohingya crisis which will increase international demand for the Burmese military to halt their abhorrent agenda.

Ultimately the choice to visit a country where the military or any force of power is violating international human right laws is deeply personal. Travelers cannot visit with the mindset that nothing has happened and must make responsible decisions when visiting the country.

For ways to directly contribute support to Rohingya, the New York Times released a vetted list of organizations, originally published in 2014, that accept donations and has kept the page up-to-date with current aid providers. Global Giving, BRAC, and Partners.ngo have also started refugee relief funds.

More like this: Check out these stunning portraits of Myanmar’s people and culture

Be a better global citizen

Nearly 2400 years ago, when someone asked Diogenes of Sinope where he came from, he said, “I am a citizen of the world.” The implications of that idea have reverberated for centuries. What does it mean if our loyalties are owed not just to our countrymen and those that share our skin color and religion, but towards humanity as a whole? How do we find common ground with people who are so fundamentally different from ourselves? What do we owe the human race?

The alternative is nationalism. 2017 was a big year for nationalism around the world, but it was also a stark reminder of how mindless and silly nationalism is — perhaps the most striking example was when the leaders of two nuclear powers started trading pointless, childish insults, risking an unnecessary war that could lead to nuclear winter and global catastrophe. It was an absurd moment, with two grown men risking the lives of billions simply so they could service their fragile egos, and it showed us all what nationalism really has to offer: division, destruction, and death.

2018, if there’s to be any hope for the human race, has to be the year that grassroots internationalism makes a comeback. We have to start fighting with each other rather than against each other, and we have to identify real common enemies, like climate change, nuclear war, and poverty, rather than fake or exaggerated ones, like immigration, multiculturalism, and terrorism. There’s a lot of work to do, but here are some suggestions for 2018.

1. Consider traveling less.

I know — this is a weird thing for a writer on a travel site to say. But while travel has a near-infinite number of demonstrated benefits to the individual, it can do a bit of a number on the collective. As I wrote last week, the greenhouse gas emissions associated with travel are kind of huge, and many tourists sites are straining at the recent rise in visitors. You alone, of course, don’t do a whole lot of damage when you travel, but when millions of people descend on a single spot in a National Park, it can have unintended negative consequences.

Everyone should travel, it’s true. But maybe, if you’ve already done a lot of traveling yourself, take some time off and focus on your community. One of the easiest ways to decrease your carbon footprint is to take fewer flights. And it’s always worthwhile to try out a “staycation,” where you stay at home and treat your own town, city, or state like you would any tourist destination.

2. If you do travel, travel mindfully.

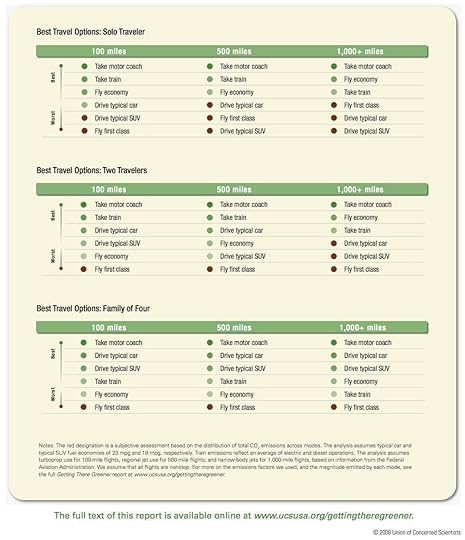

If you simply can’t talk yourself into staying home for a full year, try and travel more sustainably, and think more carefully about where you’re spending your money. The Union of Concerned Scientists did an excellent report on the most environmentally friendly ways to travel, and they created a cool little chart to help you figure out what your most sustainable bet is:

Image by UCSUSA. Click here for a larger image. You can read the full report here.

If you’re going to a city, look into the lodging options. Airbnbs are great, sure, but a lot of cities (like Barcelona and New Orleans) have had problems with “sharing economy” sites like Airbnb and Uber. So it might be better to spend a few extra bucks and go to an actual small hotel, bed and breakfast, or hostel. Likewise, try and keep your money local: don’t go to big chains, and seek out small businesses.

Sustainable tourism is huge these days, and if you do your research ahead of time, you can find some really awesome, really green trips to take. Responsible Travel and Ethical Traveler are both great resources.

3. Invest in your community.

The old global citizen cliche is “think global, act local.” But it’s a cliche for a reason — usually, the best thing you can do for the world as a whole is take care of your tiny corner of it. It is, after all, the place that you have the most power to change. So: what can you do to make your corner of the world a better place?

One easy step is to find a nearby farm offering a CSA, which stands for “Community Supported Agriculture.” Basically, you buy a share in the farm, and then once a week throughout the growing season, they send you a box full of whatever fruits and veggies they happen to be harvesting. It’s really sustainable, it’s really healthy, and it’s very affordable. This site has a tool to help you find one near you.

Next is to consider reinvesting your money locally. Sites like Community-Wealth.org can help give you an idea of how to do so, but you can start by moving your money from the big banks to smaller institutions like Credit Unions, which are more democratically run.

4. Get altruistic.

Many of our problems are structural and are going to take a long time to fix. But that doesn’t mean we can’t still do the most we possibly can in the short-term to alleviate as much suffering as humanly possible.

Effective altruism is a movement that is focused on helping people determine how to get the biggest bang for their donated buck. In short — how can I save as many lives for as little money as possible? They emphasize transparency and evidence in their selection of charities and try to maximize their impact globally. So, even though you may be an American, if you have a choice between saving one American life for $100, or ten African lives for the same $100, you would choose to save the Africans, simply because you’d be making a bigger global impact.

The two best resources for this are The Life You Can Save and GiveWell. The Life You Can Save has also put together this cool little quiz with MIT to help you examine your giving habits.

5. Start thinking of democracy as something that goes beyond voting.

One of the more frustrating parts of 2017 came when people who I may have agreed with politically started griping about how voting never changed anything, and that a candidate could win the popular vote and still lose elections, or that rich people could basically buy candidates and elections, and so on.

That’s only true because, in America, we have this warped idea that democracy ends at the ballot box. This is totally wrong. Democracy starts at the ballot box. If you vote, and the election doesn’t turn out the way you’d hoped, then don’t give up till the next election — keep fighting anyway. There are all sorts of things you can do to participate in a democracy beyond voting. You can go to town council meetings, you can write letters, you can call representatives, you can protest, you can publish articles, you can teach classes, you can organize with other like-minded people, you can go outside and pick up trash off of the streets.

Democracy is a full-time job, and it’s a really fulfilling full-time job if you dedicate yourself to it. If you look at the news and get depressed, don’t just wallow in that feeling — get outside. Do something.

6. Volunteer.

For the longest time, I didn’t volunteer for anything. I thought volunteering meant working at a soup kitchen, which wasn’t really my thing. Nothing against soup kitchens, it just never felt like a fit to me. So I did nothing. And I always felt a little bit like I was failing my community. Last year, after spending maybe the third weekday in a row at my local library, I realized that the library was something I cared deeply about and that it may be the perfect volunteer opportunity for me.

I’ve since gotten deeply involved in our town library, and it’s like a whole new world has opened up to me — I’d never realized all that libraries do beyond just lending books. They’re a community center, a place for people to rest when they have nowhere else to go during the day, a place of learning, a place of historical preservation, and a place of research.

The point is — don’t just volunteer for the sake of volunteering. Find something that fits, and it’ll become a fulfilling part of your life.

More like this: Volunteering will make you a happier person. Here’s how.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers