Terry Farish's Blog, page 20

January 11, 2016

ALA and Me

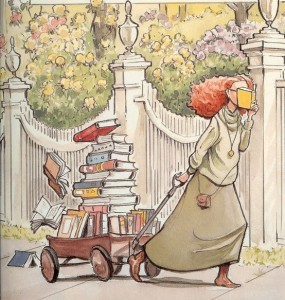

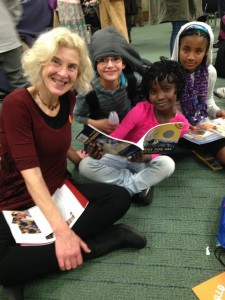

This is an illustration by David Small from Sarah Stewart’s book, The Library. I got some notecards with this illustration at the ALA conference this weekend in Boston and it makes me feel like a kid and how easy it would be to slip into this person, walking while reading with a stash as back-up. That was me. I got a new stash of books at the conference. I got galleys of Nancy Bo Flood’s Soldier Sister, Fly Home and Ben Rawlence City of Thorns. I also for the first time signed books at ALA. I met librarians and writers from all the places I’ve lived as I signed LUIS PAINTS THE WORLD My favorite thing to do was meet people who asked me to sign a book for a child not yet born.

This is an illustration by David Small from Sarah Stewart’s book, The Library. I got some notecards with this illustration at the ALA conference this weekend in Boston and it makes me feel like a kid and how easy it would be to slip into this person, walking while reading with a stash as back-up. That was me. I got a new stash of books at the conference. I got galleys of Nancy Bo Flood’s Soldier Sister, Fly Home and Ben Rawlence City of Thorns. I also for the first time signed books at ALA. I met librarians and writers from all the places I’ve lived as I signed LUIS PAINTS THE WORLD My favorite thing to do was meet people who asked me to sign a book for a child not yet born.

December 22, 2015

Discussion Guide for Either the Beginning or the End of the World by “I’m Your Neighbor”

Either-the-Beginning-or the End of the World Discussion Guide

This Discussion Guide is created by the “I’m Your Neighbor” project that celebrates books across cultures for children and young adults. “I’m Your Neighbor” offers a wide-ranging reading list of multicultural books and ideas for engagement activities in which the books are used to build bridges of understanding among us all.

December 8, 2015

I Love the Novel Any Way I Can

When I was a child, I always wished my family would talk to each other the way people talked to each other in books. Or maybe I wanted my family to reveal their hearts or even know their hearts and use language as a way to speak truths to each other. Books fed this hunger for me. I don’t think it was just my family. There could be other families that build up hurts and walls and protections, but in books – novels – something cracked and people had to talk to each other or leave or die. I think now of the books that cross cultures; there would be no plot if the characters weren’t forced to engage with each other. Maybe we all need books like I did as a child, to reveal us to one another and we can feel safe – it’s just a story – but we can gain small entry to one another. And a taste of the wholeness in the world.

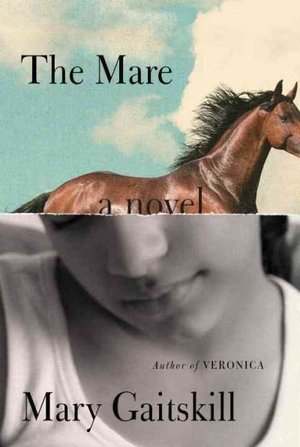

I’m just finishing up teaching a Creative Writing class with young college students in their first year. They didn’t flinch from hard material. Gender, Class, Violence, Love, Family. But why stories? That’s what I wanted to talk about with them now that we’ve done it. Here’s a bit of our journey through some of the books we read which take us, in the end, to HOW HARD it is for us to talk to each other, across generations, across class, across cultures. I told the students about one book in which there is success of talking across species (and culture and class), The Mare by Mary Gaitskill. We even crossed genres in the class, from picture books to YA, and even, yes, “Night Vale.”

First, we looked at Bear by John Schoenherr to read pure, clean sentences.

We started one story early on and continued reading it over many weeks.

“In the convent, Sister Ursula’s first submission began, I was known as the whore’s child.” Sister Ursula is driven to write her memoir and in writing, finds herself.

We read more contemporary short stories including Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral” about perception – an opening to a new perception – and listened to a podcast of “Welcome to Night Vale” by Joseph Fink and Jeffry Cranor.

“The City Council announces the opening of a new dog park at the corner of Earl and Sommerset, near the Ralph’s. They would like to remind everyone that dogs are not allowed in the dog park. People are not allowed in the dog park. It is possible that you will see hooded figures in the dog park. DO NOT APPROACH THEM. DO NOT APPROACH THE DOG PARK.” from the pilot episode of “Welcome to Night Vale.”

We worked in writing groups. Sometimes they helped. Something they didn’t. But students wrote short story scenes. They revised.

We read sonnets, from Shakespeare’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” to Helen Frost’s novel in sonnets and sestinas

“I love this girl whatever way I can,

too young to be her father, too old to be her man.”

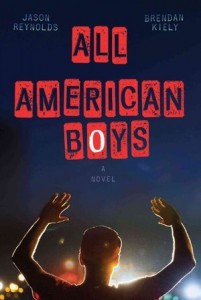

We ran out of time to read, but we talked about this new YA novel, All American Boys, written in a collaboration between a white man and a black man.

“There was blood pooling in my mouth—tasted like metal. There were tears pooling in my eyes. I could see someone looking at me, quickly fading into a watery blur. Everything was sideways. Wrong. My ears were clogged, plugged by the pressure. All I could make out was the washed-out grunts of the man leaning over me, hurting me, telling me to stop fighting, even though I wasn’t fighting, and then the piercing sound of sirens pulling up.

My brain exploded into a million thoughts and only one thought at the same time—

please

don’t

kill me.”

Velvet is a Dominican-American 13-year old form Brooklyn who goes to the country through the Fresh Air Fund to spend the summer with a white professor and his artist wife in upstate New York. She’s angry and tough, and falls for horse who has been abused and brought back to health.

Velvet is a Dominican-American 13-year old form Brooklyn who goes to the country through the Fresh Air Fund to spend the summer with a white professor and his artist wife in upstate New York. She’s angry and tough, and falls for horse who has been abused and brought back to health.

Reviewer Ellen Akins writes , “No one can speak fully or clearly to one another in this book, and yet they all communicate like crazy, with each other and with us — even to the point of a wordless epiphany. When, in the barn alone with her mare, Velvet comes to an understanding — “I am doing it for this” — she says, “If somebody asked me what this was, I wouldn’t be able to tell them. But I knew, I knew.”

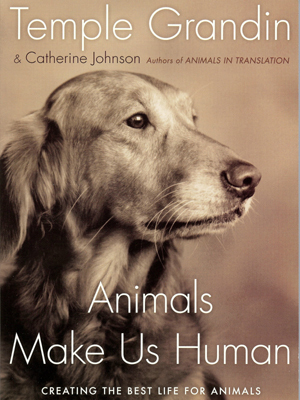

Animals came to be a thread through the class. We posted pictures of our animals on Blackboard. We wrote stories and poems about them. We met Timothy, a languid cat, Faron, a pit bull, chickens, goats, ferrets, a parrot.

Our (problematic) text was The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Stories, ed. by Tobias Wolff. And we ended with a quote from Wolff’s preface:

“Chekhov says of one of his characters, “he had a talent for humanity.” It is this quality, above all, that puts these writers on common ground – the ability to breathe into their work distinct living presences beyond their own: imagined others fashioned from words, who somehow take on flesh and blood and moral nature. This is, I believe, miraculous in itself, and miraculous in its consequences.”

Yes, miraculous.

Why Read Stories

For our last meeting of an introduction to Creative Writing, I’ve been trying to figure out what to gather up for our last class. These are young college students in their first year. They didn’t flinch from hard material. Gender, Class, Violence, Love, Family

Why stories? Why do we do this? That’s what I want to talk with the about.

First, we look at Bear by John Schoenherr to read pure, clean sentences.

We started one story early on and continued reading it over many weeks.

“In the convent, Sister Ursula’s first submission began, I was known as the whore’s child.”

We read more contemporary short stories including Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral” about perception – an opening to a new perception and a podcast of “Welcome to Night Vale” by Joseph Fink and Jeffry Cranor.

“The City Council announces the opening of a new dog park at the corner of Earl and Sommerset, near the Ralph’s. They would like to remind everyone that dogs are not allowed in the dog park. People are not allowed in the dog park. It is possible that you will see hooded figures in the dog park. DO NOT APPROACH THEM. DO NOT APPROACH THE DOG PARK.” from “Welcome to Night Vale.”

We worked in writing groups. Sometimes they helped. Something they didn’t. But students wrote short story scenes. They revised.

We read sonnets. From Shakespear’s “Shall I compare the to a summer’s day?” to Helen Frost’s novel in sonnets and sestinas

“I love this girl whatever way I can,

too young to be her father, too old to be her man.”

“There was blood pooling in my mouth—tasted like metal. There were tears pooling in my eyes. I could see someone looking at me, quickly fading into a watery blur. Everything was sideways. Wrong. My ears were clogged, plugged by the pressure. All I could make out was the washed-out grunts of the man leaning over me, hurting me, telling me to stop fighting, even though I wasn’t fighting, and then the piercing sound of sirens pulling up.

“There was blood pooling in my mouth—tasted like metal. There were tears pooling in my eyes. I could see someone looking at me, quickly fading into a watery blur. Everything was sideways. Wrong. My ears were clogged, plugged by the pressure. All I could make out was the washed-out grunts of the man leaning over me, hurting me, telling me to stop fighting, even though I wasn’t fighting, and then the piercing sound of sirens pulling up.

My brain exploded into a million thoughts and only one thought at the same time—

please

don’t

kill me.”

Velvet is a Dominican 13 year old form Brooklyn who goes to the country through the Fresh Air Fund to spend the summer with a white professor and his artist wife in upstate New York. She’s angry and tough.

Velvet is a Dominican 13 year old form Brooklyn who goes to the country through the Fresh Air Fund to spend the summer with a white professor and his artist wife in upstate New York. She’s angry and tough.

Reviewer Ellen Akins writes , “The Mare” … gives eloquent voice to the ineffable thoughts and feelings experienced across boundaries of age and race and class and gender — and even, in this case, species….No one can speak fully or clearly to one another in this book, and yet they all communicate like crazy, with each other and with us — even to the point of a wordless epiphany. When, in the barn alone with her mare, Velvet comes to an understanding — “I am doing it for this” — she says, “If somebody asked me what this was, I wouldn’t be able to tell them. But I knew, I knew.”

Animals came to be a thread through the class. We posted pictures of our animals on Blackboard. We met Timothy, a languid cat, Faron, a pit bull, chickens, goats, ferrets,

“We need to see ourselves acted upon by a story, outraged, exposed, in danger of heartbreak and change.” Tobias Wolff

“Reading makes immigrants of us all. It takes us away from home, but more important it finds homes for us everywhere.” Jean Rhys

December 3, 2015

“Chnam Oun 16” and Either the Beginning or the End

“Chnam Oun 16″ and Either the Beginning or the End

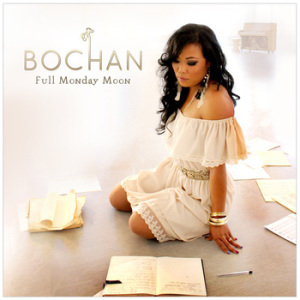

When I heard the song “I am 16″ – “Chnam Oun 16″ – by Bochan, I thought she must speak for so many Cambodian daughters, mothers, and grandmothers with her gripping lyrics of survival. And Bochan has just said, Yes, we can use her song as the audio for a book trailer for Either the Beginning, and I think nothing in the world could honor my character Sofie and her family more. Thank you, Bochan. Her dad was a pop musician in Cambodia in the early 1970s, playing psychedelic music brought to South East Asia from the west. Bochan brings his version – and her own interpretation – to America. Bochan writes, “I get to chose my identify.” Sofie wants this same thing.

When I heard the song “I am 16″ – “Chnam Oun 16″ – by Bochan, I thought she must speak for so many Cambodian daughters, mothers, and grandmothers with her gripping lyrics of survival. And Bochan has just said, Yes, we can use her song as the audio for a book trailer for Either the Beginning, and I think nothing in the world could honor my character Sofie and her family more. Thank you, Bochan. Her dad was a pop musician in Cambodia in the early 1970s, playing psychedelic music brought to South East Asia from the west. Bochan brings his version – and her own interpretation – to America. Bochan writes, “I get to chose my identify.” Sofie wants this same thing.

“I Am 16″ is on Bochan’s album Full Monday Moon. The Cambodian Alliance for the Arts says the album “captures the Cambodian-American experience, a conglomeration of varied cultural influences. The album isn’t purely one thing, and neither is contemporary Khmer identity—it’s a heady, explosive mix that creates something new, both loyal to its influences and different from them.” Here’s some more about Bochan:

“I Am 16″ is on Bochan’s album Full Monday Moon. The Cambodian Alliance for the Arts says the album “captures the Cambodian-American experience, a conglomeration of varied cultural influences. The album isn’t purely one thing, and neither is contemporary Khmer identity—it’s a heady, explosive mix that creates something new, both loyal to its influences and different from them.” Here’s some more about Bochan:

Studio 360 “Bochan: A Cambodian-American Idol

PRI – “Oakland Singer fuses Cambodian Psychedelic Rock and Hip Hop

“Chnam Oun 16″ – “I am 16″ and book trailer for Either the Beginning or the End

When I heard the song “I am 16″ – “Chnam Oun 16″ – by Bochan, I thought she must speak for so many Cambodian daughters, mothers, and grandmothers with her gripping lyrics of survival. And Bochan has just said, Yes, we can use her song as the audio for a book trailer for Either the Beginning, and I think nothing in the world could honor my character Sofie and her family more. Thank you, Bochan. Her dad was a pop musician in Cambodia in the early 1970s, playing psychedelic music brought to South East Asia from the west. Bochan brings his version – and her own interpretation – to America. Bochan writes, “I get to chose my identify.” Sofie wants this same thing.

When I heard the song “I am 16″ – “Chnam Oun 16″ – by Bochan, I thought she must speak for so many Cambodian daughters, mothers, and grandmothers with her gripping lyrics of survival. And Bochan has just said, Yes, we can use her song as the audio for a book trailer for Either the Beginning, and I think nothing in the world could honor my character Sofie and her family more. Thank you, Bochan. Her dad was a pop musician in Cambodia in the early 1970s, playing psychedelic music brought to South East Asia from the west. Bochan brings his version – and her own interpretation – to America. Bochan writes, “I get to chose my identify.” Sofie wants this same thing.

“I Am 16″ is on Bochan’s album Full Monday Moon. The Cambodian Alliance for the Arts says the album “captures the Cambodian-American experience, a conglomeration of varied cultural influences. The album isn’t purely one thing, and neither is contemporary Khmer identity—it’s a heady, explosive mix that creates something new, both loyal to its influences and different from them.” Here’s some more about Bochan:

“I Am 16″ is on Bochan’s album Full Monday Moon. The Cambodian Alliance for the Arts says the album “captures the Cambodian-American experience, a conglomeration of varied cultural influences. The album isn’t purely one thing, and neither is contemporary Khmer identity—it’s a heady, explosive mix that creates something new, both loyal to its influences and different from them.” Here’s some more about Bochan:

Studio 360 “Bochan: A Cambodian-American Idol

PRI – “Oakland Singer fuses Cambodian Psychedelic Rock and Hip Hop

November 19, 2015

Manchester, NH Refugees celebrate literacy with CLiF

JOSEPH’S BIG RIDE. Joseph lived in Kakuma refugee camp where all he wants is one thing: to ride a bicycle. When he comes as a refugee to America, he still wants that one thing – if he could just ride a bike. Joseph is 7, like a lot of the kids I see tonight.

JOSEPH’S BIG RIDE. Joseph lived in Kakuma refugee camp where all he wants is one thing: to ride a bicycle. When he comes as a refugee to America, he still wants that one thing – if he could just ride a bike. Joseph is 7, like a lot of the kids I see tonight.Amadou said to me, These parents love their children but sometimes they are working at night and trying to solve their own problems in a new country and sometimes they don’t sit down with their children. This program is so good because the parents can be with their children and books. On my way out I passed a very large painting. A teacher told me “many hands created it.” It was a landscape and beneath it were lines of a poem beginning with “I’m from….” that each child had created. Here are some of the lines:

I’m from old, romantic, Hindi songs.

I’m from Beldangi, near river and forest, close to the desert.

I’m from a beautiful place, I am from Iraq.

October 30, 2015

REFORMA: “A book is a companion that will bring you light and comfort.”

My article was first opublished by The Pirate Tree: Social Justice and Children’s Literature

My article was first opublished by The Pirate Tree: Social Justice and Children’s Literature

The group Reforma, an American Library Association affiliate, and IBBY, the International Board of Books for Young People, have, at their core, the driving belief that every child has the right to read.

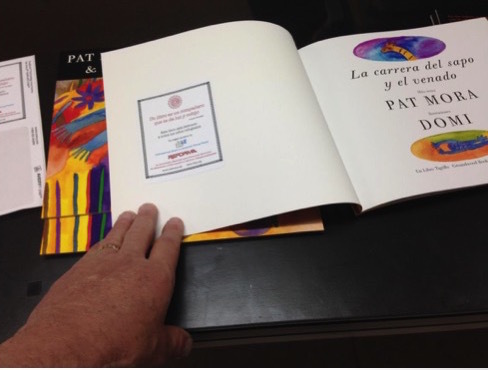

Three Pirate Tree reviewers, Nancy Bo Flood, Lyn Miller-Lachmann and I spoke at the recent IBBY regional conference in New York City. Among our colleagues was Oralia Garza de Cortes, past president of Reforma, who has been working on a Reforma project with Patsy Aldano to bring books to Central American children who crossed the border into Texas, fleeing violence in their home countries. They have been held at detention centers and later given support by Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley in McAllen, Texas, the town to which Garcia and Aldano traveled. I want to share the story we learned from Oralia Garcia de Cortes and Patsy Aldano.

Reforma received a grant from IBBY’s “Children in Crisis” project to purchase Spanish-language books for child refugees. The parents of the children had paid “coyotes” to guide them across the border. Aldano said about the children, “These are refugees. They will die if they stay where they live.” And when the children arrived at the Texas border, they told the guards they wanted asylum so that they might petition to gain refugee status. They are mostly from Honduras, the country with the highest homicide rate in the world, Reforma reports, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

Reforma received a grant from IBBY’s “Children in Crisis” project to purchase Spanish-language books for child refugees. The parents of the children had paid “coyotes” to guide them across the border. Aldano said about the children, “These are refugees. They will die if they stay where they live.” And when the children arrived at the Texas border, they told the guards they wanted asylum so that they might petition to gain refugee status. They are mostly from Honduras, the country with the highest homicide rate in the world, Reforma reports, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

Each of the books donated to the children in detention held a book plate with the words, “A book is a companion that will bring you light and comfort.” 186,233 children have crossed into Texas since 2009. The detention centers have since released many children, some with their mothers. And many keep coming. When children leave detention they have very few resources, and Catholic Charities of Rio Grande Valley has been instrumental in providing basic supplies. Reforma and Catholic Charities of the Rio Grand Valley are organizations in extreme need of donations and resources. Reforma offers this link to see more about the project and to make a donation. http://refugeechildren.wix.com/refuge...

For children making their way on buses traveling in search of family members in the U.S., Reforma has created a library card to travel. It says, “Please welcome these children to your library.”

Barry Lopez knows this story. He wrote these words in his classic book, Crow and Weasel: “Sometimes a person needs a story more than food to stay alive.”

October 26, 2015

“The whole human race is tribal,” says Susan Cooper. “Authors have to be brave.”

The IBBY (International Board of Books for Young People) regional conference in New York City was a call to action. IBBY is a grand, activist organization marching, bearing the best of the world’s literature created for children. Reforma is an American Library Association affiliate organization that received a grant from IBBY’s “Children in Crisis” project to provide books to child refugees fleeing violence in Latin America. The children surrender themselves at the Texas border. Patty Aldano and Oralia de Cortez Garza told us about their visit to bring books to a detention center where the children are held and where they told the officials that children need books. “A child who reads will be an adult who thinks.” It took several tries to gain entrance.

The IBBY (International Board of Books for Young People) regional conference in New York City was a call to action. IBBY is a grand, activist organization marching, bearing the best of the world’s literature created for children. Reforma is an American Library Association affiliate organization that received a grant from IBBY’s “Children in Crisis” project to provide books to child refugees fleeing violence in Latin America. The children surrender themselves at the Texas border. Patty Aldano and Oralia de Cortez Garza told us about their visit to bring books to a detention center where the children are held and where they told the officials that children need books. “A child who reads will be an adult who thinks.” It took several tries to gain entrance.

Cuban-American writer Margarita Engle, through her years of writing and at the conference. made a plea for dual language books so that her books and others’ books can be read by people separated by politics and history. “So many children have families divided by history.”

On my panel with Nancy Bo Flood and Lyn Miller-Lachmann – Nancy has named us the “War Panel” – we made the case for the power of literature to bring a child’s experience of war into the light. The books allow readers to step across cultures and are testament to the dignity and agency of the children and families who survive.

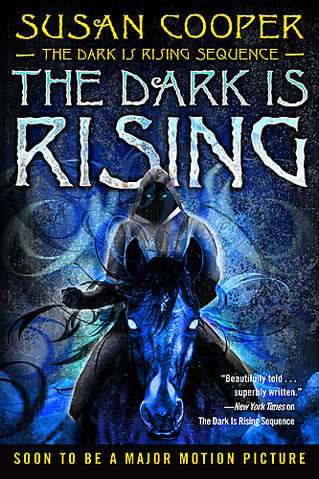

And Susan Cooper, author of the classic The Dark is Rising Sequence, shaped by Tolkein and C.S. Lewis with whom she studied at Oxford, asked, “Will we ever affect the hostility children inherit from their parents?” She said we writers must try. “Our job as writers is to step out of ourselves.” She said, “The whole human race is tribal. We must have cross-cultural communication. Don’t let your fear stop you.”

I had such long, wonderful years as a passionate reader of high fantasy with Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials being the absolute high. Children’s books historian Marcus Leonard – who was at IBBY, of course – wrote somewhere that fantasy doesn’t solve the world’s problems, but when you re-enter the world, you see the problems with new eyes and new perspectives. Which is always the power of a book, inviting us at all our ages to enter our imaginations. Leonard’s consistent theme: “There are no good books that are only for children.”