Karyn Hall's Blog, page 18

April 26, 2012

Expressive Writing

When thinking about people who are emotionally sensitive, you might be most likely to think of the individual who cries easily and who shows her emotions openly. But there are many different types of emotionally sensitive people.

Type C Person

In the book The Spiritual Anatomy of Emotions, Michael Jawer discusses the Type C person. A Type C individual is a stoic, a denier of strong feelings and has a calm, unemotional demeanor.

This person has a tendency to people please, is not assertive, and tends to feel helpless and hopeless. He is at risk for autoimmune disorders from asthma to lupus. Type C people tend to say they aren’t upset but experience strong sensations in their bodies that indicate otherwise. They don’t say no or defend their personal integrity. Their emotions have no outlet. For the Type C person who is emotionally sensitive, finding a way to cope with emotions is critical.

Different coping strategies work for different people. For some who struggle with intense feelings about events that have happened, but have difficulty expressing themselves, expressive writing might be particularly effective. Finding a way to label and express emotions is a part of coping.

Writing and Trauma

In the 1970′s and early 1980′s James Pennebaker, a social psychologist in Austin, investigated the effects of a writing technique for people who had experienced traumatic experiences such as divorce, abuse, deaths of spouses and the Holocaust. He confirmed that following a difficult emotional event people are more likely to become depressed or ill, experience changes in body weight and sleeping habits, and even die of heart disease and cancer at higher rates than those not traumatized. People who suffered a traumatic experience and kept it secret experienced more severe consequences than those who did not keep it secret.

Dr. Pennebaker discovered that most people who write in a certain way about upsetting events in their past gain an improved mood and health. The writing technique is not about reliving the event, but about gaining a better understanding or finding meaning in the event. Sometimes the meaning is very difficult to find.

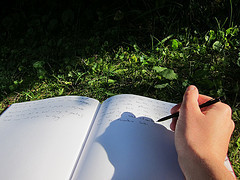

A Special Place and A Ritual for Writing

In his book, Writing to Heal, Dr. Pennebaker suggests that people who try expressive writing create a special place to write. A calming, nurturing environment, separate from where you work or do other activities, is advised. You’ll want a place where you can be alone for a while. Set up the room in the same way each time you write and try to write at the same time each day. Create your own ritual. You may want to meditate before or after.

A Few Don’ts

What not to do? Don’t write about anything that you cannot handle. In addition, don’t write about a recent event. The technique is usually not helpful immediately after an event has occurred. You need to manage your immediate reactions and be able to use your logical mind first. If you are in therapy, discuss this option with your therapist. If you are not coping well in general, don’t use expressive writing.

Guidelines for Writing

Pennebaker’s instructions are to write for about twenty minutes on four consecutive days. You can write about the same topic each day or different topics. Write continuously and don’t correct your grammar or spelling. Write about your deepest thoughts and feelings about an event that happened that has been influencing your life. Let go and explore the event in a deep and thoughtful way. Write what happened (the facts), how you felt about it at the time it occurred and how you feel about it now. You might write about how the event has affected your relationships with those you love and others you know personally as well as your working relationships.

On the second writing day, go even deeper into your emotions and thoughts. You might want to write more about how it has affected your relationships with those you love and your life in general.

On the third writing day continue to focus on the current emotions and thoughts that you have about the event that are affecting your life the most. Don’t repeat what you have already written. Explore the event from different perspectives and different points of view. Write about what you are feeling as you explore this. How has this shaped you as a person? What makes you feel the most vulnerable?

Write from your wise mind, using observe and describe. State the facts as you know them and separate writing about facts from writing about emotions and thoughts.

On the last writing day, continue writing about your emotions and thoughts. Try to cover any aspects you haven’t written about yet. What have you learned, gained and lost as a result of this experience you are writing about? Try to create a meaningful story that you can take with you into the future.

For more specific information about expressive writing, and instructions, Dr. Pennebaker’s website is at http://www.utexas.edu/features/archiv....

April 7, 2012

How Stereotypes Affect The Emotionally Sensitive

A research study completed years ago has always fascinated me. In the 1960′s Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson administered a test to all students in an elementary school and gave the results to the teachers. They told the teachers that based on the test results some students were particularly likely to excel academically in the upcoming year whereas others were not.

The "gifted" students were actually chosen by drawing names out of a hat, not by their performance on the test. In fact, the test was bogus and didn't really measure anything. At the end of the year the students identified as gifted scored significantly higher on an actual IQ test than students who weren't labeled as gifted, though in truth there was no difference in the groups at the beginning of the year.

That is an amazing result. The authors believed that the only way this could have happened is through a self-fulfilling prophecy in the minds of the teachers. The students themselves did not know they had been designated as high-achievers (or not) and neither did their parents. Only the teachers knew. The researchers believed that the teachers' expectations caused them to act in ways that improved the performance of the students who were labeled as being intellectually brighter.

Identity Contingency

How could someone just thinking a certain way about you actually change your performance? Is it just that they work harder with you or give you the benefit of the doubt more often? And did the teachers' attitudes negatively influence the scores of the students not seen as gifted?

Recent research suggests that there's another component other than the teachers working harder with the students labeled as gifted. Claude Steele's work, as reported in his book Whistling Vivaldi, would suggest that part of the way self-fulfilling prophecy works is that people, even young children, pick up on cues about the expectations of others and the messages given to them by a setting, though they may not be conscious of these messages.

Even young children are often aware of general stereotypes. Performance results for all ages at many different tasks are dependent to a surprising degree on what Steele calls identity contingency.

Identity contingencies are the things you have to deal with in a situation because you have a given social identity, such as being female, male, an executive or whatever job you perform, black, white, oriental, geeky or emotionally sensitive. Some identity contingencies are more serious than others, but they all carry a sort of stigma.

In general the emotionally sensitive may be seen as too soft, too touchy-feely, or even unstable. The stereotype that goes with being emotionally sensitive includes being seen as not serious about business or career, weak as a person, unreliable, over-reactive, high maintenance, and less professional than those who are not viewed as emotionally sensitive. Many who are emotionally sensitive fear being stereotyped in this way which of course adds stress when in a situation where the stereotype could be applied to them.

Stereotype Threat

Stereotype threat is when you are in a situation where the stereotype could be applied to you and result in your being treated negatively. Thus someone who is emotionally sensitive may be on high alert in certain situations, fearful of showing "too much" emotion and being categorized in a negative way that would have consequences for their relationships and/or their career.

The fear is real. Evidence consistently shows that consequences tied to your social identity make a difference, from the way you perform in certain situations to the careers and friends you choose. To do well in a situation where a social stereotype is in play, individuals experience enormous pressure.

For example, emotionally sensitive people may go to work each day determined to not show emotion and fearful of the labels that others might give them. The added tension from the worry about being labeled is likely to make it even more difficult to manage their emotions.

Social identity threat does not have to be a known threat, with a particular bad thing that could happen, like being labeled as unstable or passed over for a promotion. Social identity threat can exist even if the person is uncertain that anything negative would happen if they were labeled. The person only has to believe that something negative could happen. Negative consequences include embarrassment, humiliation, possible social rejection, awkward interactions, lost career opportunities, being judged, and being dismissed or discounted.

As Steele points out, the problem is that the pressure to disprove a stereotype changes how you are in a situation. It gives you an extra task. In addition to learning new skills, knowledge and ways of thinking in a new situation, or in addition to trying to perform well in a workplace, the person is trying to overcome the negative stereotype. This multi-tasking is stressful and distracting and interferes with performance, especially when trying to learn something new.

When you realize that this stressful experience is chronic in a certain setting, such as that you will always be trying to prove that being emotionally sensitive doesn't mean this or that, you may drop out. Or maybe avoid any situation that involves stereotype threat. Dropping out may confirm the stereotype for some and raise your own doubts about yourself.

How Stereotype Threat Impairs Your Performance

Steele states that identity threats negatively impact a broad range of human functioning. First, the threat of confirming the stereotype makes you vigilant to all things relevant to the threat, and to what your chances of avoiding it are. For the emotionally sensitive, this would mean any interaction or situation they perceived as having an emotional component.

Second, identity threats raise self-doubt and create repeated thoughts/worries about how valid the doubts are.

Third, the self-doubt leads to constant monitoring of how well you're doing which impairs performance. The pianist who plays almost without thinking has a "flow" of performance. But should the pianist be wracked with doubt and evaluate every chord he plays, his performance will suffer. Finally identity threats pressure people to suppress threatening thoughts, thoughts about not doing well or about bad consequences of confirming the stereotype. This requires energy and is exhausting.

Identity threat brings about a kind of panic, according to Steele. Your mind races, your blood pressure rises, you begin to sweat, you redouble your efforts to perform well. In your mind you try to refute the stereotype and what you can't refute you try to suppress. Your alertness to threats increases and this further suppresses the brain activity critical to performance and functioning.

The more you care, the more frustrated you are, and the highter the stakes of performance, the more panicked you may be. If the threat is part of an ongoing situation in you life–an ongoing experience in a workplace for example, or in school, then this reaction can become chronic. And, though it is difficult to believe, you're probably aware of some of this defending and coping, but much of the time you miss it.

A mind trying to defeat a stereotype leaves little mental capacity free for anything else you're doing.

So stigma matters not only in the way others react to you, but in your own performance and choices. Stereotypes hurt in ways we may not even realize.

photo credit: 1CreativeSoul

photo credit: 1CreativeSoul

March 28, 2012

An Introduction to DBT

Relationships and the Emotionally Sensitive

Relationships can be a roller-coaster ride for the emotionally sensitive. Emotionally sensitive people often love fiercely and intensely. They also become hurt, angry and sad more quickly and more intensely than others do. Their emotions sometimes lead to relationships with lots of ups and downs.

They may love their partner or friend but frequently be so angry and hurt they cannot be around the person, perhaps over an issue that others do not understand. They may believe that they hate a person at a certain time and they do. They may believe they never want to speak with or see the person again. But those thoughts, based on feelings of hurt and anger, often fade after the emotions pass. Then they are often racked with shame that they pushed someone away.

Shame blocks relationships. Because of their shame, some have difficulty acknowledging that they acted on emotions that they no longer feel. That acknowledgement can seem like their feelings were wrong and that is invalidating of their experience, which was real and true to them at the time. They may believe that makes them "wrong" as a person, inadequate or broken. Actually, most often the emotionally sensitive are acting on a thought or experience that is completely understandable, but their reactions are more intense than others may be able to understand.

The loss of relationships can be traumatic. Sometimes the ups and downs that the emotionally sensitive experience end in the loss of a relationship. Others may become confused or frustrated with the emotional changes. The loss of a relationship is so painful for many that they often do not know how to cope. For some, they decide relationships aren't worth the pain. They withdraw and avoid relationships. Others may blame themselves and feel deep anger that they aren't able to maintain relationships. They then attempt to push their emotions down, attempting to not express them. They may succeed for a time. But emotions cannot stay pushed down without some consequence. For example, some individuals may "blow up," and hate themselves for failing to keep their emotions in check. Pushed down emotions can also have other consequences such as health problems.

Loss of a relationship occurs for many other reasons. Sometimes it is the cycle of life, that everything changes and nothing is permanent but change. Loved ones may move away or die. There may be arguments that aren't resolved or disappointments that aren't forgiven.

Sometimes the emotionally sensitive experience a kind of traumatic reaction around relationships. Perhaps because of a history of lost relationships, perceived/actual rejections, an insecure or neglectful relationship with their parents, or other past experiences, the emotionally sensitive may be hyper-alert for any signs of judgment, neglect, or discontent by others. This hyper-alertness is a part of protecting themselves but often leads to the very result they fear: the loss of a relationship. They may blame others or themselves, but the pain is intense either way.

Letting go of a relationship, regardless of the reason, is often one of the most difficult situations for the emotionally sensitive. When they have feel the loss of a relationship, the emotionally sensitive are in agony. They often describe themselves as feeling empty and alone. They long for the return of the relationship. Sometimes that longing is not logical but based on pure feeling. They want the relationship they had before the disruption that occurred.

The pain of not having it can be overwhelming. They may act in ways that are further destructive, such as repeated calling or defending themselves to salvage the relationship. They may also be self-destructive in trying to alleviate their pain.

A Few Coping Strategies

When suffering the pain of a loss of a relationship, distracting yourself is one way of coping. Finding a way to give yourself a break from the pain helps your resiliency. An activity that absorbs your attention is best. You may also remind yourself that though you think you will never recover, emotions do fade over time.

Finding comfort in others or providing comfort and compassion to yourself is important. Getting involved in helping others and focusing on being kind to others works for some. Seeking solace in spirituality and in finding meaning to the experience may help you cope until the pain is no longer so acute.

Finally, learning from the experience and developing new skills, whether in maintaining new relationships or in choosing people with whom to have relationships, may help change a repetitive pattern.

photo credit: mcgeesmixtapes

photo credit: mcgeesmixtapes

March 23, 2012

Understanding Validation

Have you ever wished you could take back an email that you sent when you were emotionally upset? Or maybe you made some statements when you were sad that you didn't really mean or agreed to something when you were thinking with your heart that you later regretted ? Or maybe you wanted to be supportive and helpful to someone you love but couldn't because your own emotions made it difficult?

Communicating when overwhelmed with emotion does not usually work well. Being overwhelmed with emotion is not a pleasant experience. For emotionally sensitive people, managing their emotions so they can communicate most effectively and with the best results means learning to manage the intense emotions they experience on a regular basis.

Validation from others is one of the best tools to help emotionally sensitive people manage their emotions effectively. Self-validation is one of the best ways for emotionally sensitive people to manage their own feelings. Self-validation is the step that comes before self-compassion. Acknowledging that the internal experience exists and is understandable comes before self-kindness.

Understanding Validation

Validation is a simple concept to understand but difficult to put into practice.

Validation is the recognition and acceptance of another person's internal experience as being valid. Emotional validation is distinguished from emotional invalidation, in which your own or another person's emotional experiences are rejected, ignored, or judged. Self-validation is the recognition and acknowledgement of your own internal experience.

Validation does not mean agreeing with or supporting feelings or thoughts. Validating does not mean love. You can validate someone you don't like even though you probably wouldn't want to.

Why is Validation Important?

Validation communicates acceptance. Humans have a need to belong and feeling accepted is calming. Acceptance means acknowledging the value of yourself and fellow human beings.

Validation helps the person know they are on the right track. Life can be confusing and difficult. Feedback from others that what you are experiencing is normal or makes sense lets you know that you thinking and feeling in understandable ways. Your internal experience does not have to be the same as anyone else's but it helps to know that your experiences is understandable. Or not.

Validation helps regulate emotions. Knowing that you are heard and understood is a powerful experience and one that seems to relieve urgency. Some say it's because when we don't feel understood it creates thoughts of being left out or not fitting in. Those thoughts lead to fear and maybe panic because of the importance of being part of a group is critical for survival, especially in the early days of mankind, and of the potential loss of love and acceptance which is a basic need. Whatever the reason, validation helps soothe emotional upset.

Validation helps build identity. Validation is like a reflection of yourself and your thoughts by another person. Your values and patterns and choices are highlighted and that helps people see their own personality characteristics more clearly.

Validation builds relationships. Feeling accepted builds relationships. Some research shows that chemicals related to feeling connected are released when someone is validated.

Validation builds understanding and effective communication. Human beings are limited in what they can see, hear and understand. Two people can watch the same event occur and see different aspects and remember important details differently. Validation is a way of understanding another person's point of view.

Validation shows the other person that they are important. Whether the person being validated is a child, a significant other, a spouse, a parent, a friend, or an employee, validation communicates that they are important to you and you care about their thoughts and feelings and experiences. Validation also shows the other person that you are there for them.

Validation helps us persevere. Sometimes when change is very difficult, having the difficulty of the task recognized helps people keep working toward their goal. It seems to help replenish willpower.

A simple to understand concept, validation is powerful and often more difficult to practice than it might at first seem. In my experience, the results are well-worth the effort.

photo credit: nathancolquhoun

March 13, 2012

Managing Your Emotions, Part 2

In the previous post, Coping With A Stressful Situation: Managing Your Emotions, we discussed the importance of not acting impulsively on your upset emotions. When possible, taking a break until you are calm so your logical mind can be in charge is the best strategy.

What you do during that break is important.

There are actions that will help you manage your emotions effectively and actions that tend to increase your emotional upset. When people are angry or scared or experiencing an uncomfortable emotion, they sometimes feed the emotion, like throwing wood on a bonfire, though that's not their intention.

Don't feed the emotion by going over and over the situation. People who are emotionally sensitive are sometimes prone to rumination, meaning they repeatedly review or replay the event in their head. Rumination is a key variable for depression and tends to increase upset feelings or extend the length of time you are upset.

Though it's not always the case, rumination is often about worry. As Robert Leahy notes in The Worry Cure: Seven Steps to Stop Worry from Stopping You, productive worry occurs when the worry encourages you to take necessary or prudent action in a situation. Unproductive worry is when there is nothing you can do about the situation, no action you can take to change it.

Most of the time rumination is about unproductive worry. There are many skills to stop unproductive worry and each individual must find what works best for them. One skill is acceptance. Accepting what happened doesn't mean that you approve or agree, only that you acknowledge it occurred. You stop wishing it were different, believing it shouldn't have happened, or blaming others, and accept that it did happen.

Acceptance is also about thoughts. Accepting that you are having a thought that is upsetting to you means to stop fighting the thought or feeling. Each time you experience the thought, you label it, "That's a thought," and stop yourself from going down the "what if" path. By doing so, you are recognizing that just because we think something doesn't mean it is true. Humans have thoughts all the time that aren't reflective of reality. Many thoughts are about what is out of your control and what might happen, with no evidence at all that the outcome is likely to occur.

Check the evidence is another strategy. Identify what is most upsetting to you. Do you know if what you are thinking is true or likely to happen? Is there a way to find out? Be sure you have the facts about the situation.

Visualization can be helpful. For example, you could visualize all your upsetting thoughts being locked in a steel case and buried under the ocean. Distraction by exercising is a great option. Exercise tends to calm people and help them think more clearly. Distraction by becoming involved in a absorbing activity is also helpful.

Opposite emotion, a skill used in Dialectical Behavior Therapy, is about doing an activity that creates the opposite emotion to what you are feeling. Watching a comedy show that makes you laugh when you are depressed or anxious, or watching a scary movie when you are angry may be helpful. Thinking of people you love and who love you, or talking with them when you are angry may also work.The idea is to do an activity that creates an opposite emotion to what you are feeling.

Exhaling slowly is a way of calming. Progressive relaxation has been proven effective in lowering anxiety levels.

Don't feed the emotion by gathering evidence from the past. When people are angry or scared or experiencing an uncomfortable emotion, their minds sometimes look for additional evidence to support the way they feel, maybe to justify their feelings. They remember all the wrongs done to them or they remember other times when someone was hurtful to them. That behavior is so common it has a term for it–throwing the kitchen sink at someone. Emotions of the past only multiply the intensity of the emotion they are feeling in the present.

Don't feed the emotion by ignoring the big picture. Often a person's emotion blinds them to characteristics or actions that don't support what the person is feeling at the moment. For example, when you're angry at someone, it is unlikely you'll think of all the times that person was kind or helpful. Most have experienced this when having an argument with their spouse. For example, let's say your mate forgot to get the groceries that you needed for a party you were hosting that evening. Most likely you'll be angry and recall all the other times your partner has not come through for you, forgetting when he or she was helpful or kind. If you do this, then pushing yourself to think of the positive will allow a more balanced view.

To manage your emotions effectively, keep bringing your mind back to the present issue. Focus on what is here and now, one situation at a time. Mindfulness is a good skill to use.

Ask yourself if the emotion is justified. Just like with deciding whether worry is productive or unproductive, check out the facts to see if other emotions you are having are justified. Is there a reason to be scared or jealous, or angry? If the emotion is justified, then taking planned action based on that information is important. Marsha Linehan suggested this step in Dialectical Behavior Therapy.

Often people experience emotions that aren't justified by the facts. For example an adult bully may be annoying and unpleasant but not have the power to hurt you. Your reactions may be based more on past experiences than what is happening in the here and now. This doesn't mean you won't take action, but you can act with the knowledge that there is no true danger.

Once you know what you are feeling, you're not feeding the emotion, and you know whether the emotion is justified, then you're ready for the next steps, which we'll discuss in future posts.

photo credit: zen

March 9, 2012

Coping With Difficult Emotions, Part 1

Whether you're dealing with an emotional bully (see previous post about adult bullies) or other difficult situation, one of the first steps is to comfort yourself and manage your emotions.

The part of the brain that is responsible for decision-making and planning cannot function as well when you are filled with emotion. Acting on emotions without the thoughtfulness of the logical part of the brain usually means trouble.

Even when you're in the right about a situation, if you act impulsively and emotionally it's unlikely others will listen. They'll tell you to calm down and don't get so upset. This situation happens frequently for the emotionally sensitive and they soon believe no one listens to them. They also may find themselves reacting first and regretting later.

There are ways to learn to not act immediately on the feeling you are having. Mindfulness is a skill that helps you develop a pause between feeling and acting so you're not ruled by whatever emotion you are experiencing. Jon Kabat-Zinn defines mindfulness as "Paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally."

Marsha Linehan, the creator of Dialectical Behavior Therapy, lists three How Skills and three What Skills of mindfulness. The What Skills, meaning what you do, observe, describe and participate.

Observe means to see what is present and real without coloring it with interpretation or assumptions. Observe is to see the facts of a situation. Describe is to put words on what you see without judging. You can see that the chair is red. Saying the chair is a horrid shade of red would be a judgment. Participate means to participate fully in events with full awareness of what you are doing. This means you're not daydreaming or half-aware or clouded by emotion that you aren't paying attention to what is actually happening.

The How Skills are how you do the What Skills: One-Mindfully, Nonjudgmentally, and Effectively. One-Mindfully means to do only one thing at a time and to have your attention fully on whatever you are doing. Non-judgmentally means to just experience without labeling good or bad and Effectively means to do what works.

In the case of the adult bully, observing and describing what happened is the first step: doing this in a nonjudgmental way may be difficult. Effectively is key. Regardless of whether the other person is being fair or behaving in reasonable ways, how can you be most effective in coping with his behavior?

Wait until you are calm enough to think clearly. Strong emotions seem to compel people to take some action, whether it's to fight or run away or tend and befriend. The body is poised to act, not think or plan. This system was effective when human surivival depended on avoiding a tiger or a lion, but doesn't work so well in most of the situations people face today.

The urge to do something to protect yourself against a perceived threat can be very strong, but in most situations the urgency is not real. Acting impulsively, without thinking through the action, can make the situation worse. Then one crisis is followed by another and then another. Impulsive efforts to solve the problem usually create more problems. Soon it may seem like your life is one crisis after the other. That can be discouraging and only makes your emotional state worse. Being mindful of your emotions and your internal experience without acting on your urges and impulses is an important skill. You learn that the emotion will pass.

Be Aware of and Name Your Emotions. When you observe and describe your internal state, that is one step in managing your emotions. For some, this means taking time to identify the specific emotions they're feeling: jealousy, hurt, anger, or fear?

Sometimes anger acts as a shield against feeling hurt or scared. Knowing that your anger is a secondary emotion and that your primary emotion is fear will help you manage your feelings effectively. Knowing what you are feeling gives you more of a sense of control and gives you ideas about what action to take.

Some people have great difficulty identifying feelings and distinguishing between feelings and the bodily sensations that are the basis of emotions. This characteristic is called alexithymia. If someone is alexithymic, then learning how emotions are expressed in the body is important. Sadness is often felt in the throat, chest and belly. Anger is felt in the neck, head, shoulders, hands and arms. Fear is felt in the belly, head, face, chest, and throat.

Sometimes focusing on the body sensation, such as your throat feeling tight, is more helpful than repeating in your head how anxious you are. Saying "I'm so anxious," repeatedly may actually feed the emotion.

These are beginning steps in managing your emotions. Not acting on your emotional urges takes practice, but the peace you gain by not acting impulsively is well worth the practice time.

photo credit: AbigailPhotography

February 16, 2012

Understanding Adult Bullies

One type of emotional bully is the person who attempts to use anger as a way of protecting themselves, controlling others or as a form of connection. Anger is often a hurtful emotion for those on the receiving end. For emotionally sensitive people having someone angry at them can be devastating and result in their withdrawing, fighting, acting in unhealthy ways and experiencing hours of emotional pain.

One of the ways to cope with anger is to change your perception (see previous post on No Matter What the Problem, There Are Only Four Things You Can Do). If you blame yourself whenever someone is angry with you, or have an automatic response that isn't effective, a first step of pausing and considering the reasons for their anger could be helpful.

Spouses who verbally attack, the controlling boss, the critical parent–all may be described as angry people. Bullies are often angry people, regardless of their age. Maybe it's hard to understand why someone would bully another. After all, being chronically angry has many negative consequences for both the person who lives in anger and those around that person.

Anger is a complicated emotion but we're beginning to understand it better than ever before. There are different ways that anger can work for people, at least in the short run.

Anger is a complicated emotion but we're beginning to understand it better than ever before. There are different ways that anger can work for people, at least in the short run.

Anger as an Emotional Shield

Consider Stephanie. (Like all the names used here, that's a made-up name and doesn't refer to a real person.) Stephanie is focused on self-esteem. Focusing on self-esteem is a trap, as we know from Dr. Neff's book Self Compassion (2011). She looks for achievements to feel good about herself and assesses herself in terms of whether she is better than others in various ways, such as being smarter, more fit, wealthier, and the like. Most of the time she compares herself to people she believes are superior to her and so she constantly thinks she is worthless. She puts others down in an attempt to build herself up. Her anger is based on chronic thoughts of worthlessness and hurt.

Stephanie feels powerless and inadequate. When someone feels powerless, anger can be empowering. What a different feeling that is! For fearful people, feeling in control may be soothing and they can often get that feeling through anger.

Anger and Control

Jake verbally attacks his wife Wendy. When she returned home late from a meeting, he raged at her, demanding to know where she had been. He "knew" she was cheating on him. Wendy apologized over and over and reassured him she loved him. To avoid his anger she told her boss she couldn't stay late any more. She made many changes in her life to avoid Jake's anger. Anger for Jake is about control, and in this case, his anger is a way of controlling his fears of abandonment.

Anger and Entitlement

Allison is an ambitious professional. At work, she has a group of three or four followers who agree with just about everything she says. Allison puts others down and believes she is superior to others and deserves to be adored. When she wasn't given a promotion she knew she deserved, she was enraged. She stayed angry for months and tormented the woman who was promoted. Her anger is the result of believing the world is treating her unjustly. Allison is exhibiting a narcissistic anger–she does not feel insecure, she feels entitled.

Anger and Connection

Wesley continues to form relationships that seem promising. He has a certain level of closeness with which he is comfortable. He is fine until he talks about marriage and then he finds a reason to be angry with the one he cares about. He has the same pattern in business. He works well with someone until he thinks about having a business partner. Then he destroys the relationship by finding fault with the other person. Wesley's anger is about fear of intimacy and commitment.

Anger is often a secondary emotion, triggered by fear or hurt. Think about your child running onto the road in front of your house. Fear comes first, then anger. Sometimes the change from fear to anger happens so quickly and automatically people aren't even aware it occurred.

Steven Stosny, in his book Treating Attachment Abuse (1995) talks about anger as an emotional salve to cover up core hurts. He identifies core hurts, some of which are feeling ignored, unimportant, accused, guilty, untrustworthy, devalued, rejected, powerless, and unlovable. If someone doesn't have the ability to soothe themselves or cope with core hurts, then they may use anger as a shield. By assuring oneself and others that the hurt was not legitimate, that the other person was in the wrong, the person establishes their superiority. Thus they avoid feeling the difficult emotion.

As an example, Jake is attempting to avoid terrifying feelings of abandonment. He does not have to see himself as insecure or controlling or difficult because he is sure his wife was the one at fault.

Anger can create distance when someone is afraid of getting too close. If someone has grown up with distant parents, they may crave closeness but at the same time be afraid of it. Anger can be protective in those situations.

Anger can also be a safe way to engage with someone. I fight with you, therefore we are connected.

Anger and Pain Reduction

When a person gets angry, the brain secretes norepinephrine. Norepinephrine works much like a pain reducer. When provoked the brain also produces the hormone epinephrine, which causes a surge of energy throughout our body. The chemical reactions may be comforting as well stimulating. Some report almost addictive-like response to the adrenaline-like rush they experience when angry.

Understanding the many reasons for anger (I've just listed a few) may help you step back and consider the cause. Taking that step back can help you consider your response and what coping skills you want to use instead of reacting in an ineffective habitual way (like blaming yourself or making excuses for the other person) that may not be the best choice.

February 13, 2012

Three Components of Self-Compassion

Self-compassion is a form of acceptance, one of the four options you have no matter what the problem you face (see previous post, No Matter What the Problem, There Are Only Four Things You Can Do). Kristin Neff in her book Self-Compassion: Stop Beating Yourself Up and Leave Insecurity Behind, lists three core components of self-compassion: self-kindness, recognition of our common humanity, and mindfulness. These components are all helpful for the emotionally sensitive person.

Self-kindness is being gentle and understanding with yourself. This concept means more than not beating up on yourself and stopping harsh judgments. Self-kindness means to understand and comfort yourself, like you would a good friend. Self-kindness means comforting yourself even when you make mistakes and especially when you make embarrassing ones.

Self-kindness seems to be a form of self-soothing. Taking a bubble bath, listening to uplifting music, smelling roses and petting a dog are external ways of self-soothing while self-kindness is an internal method.

Maybe you have an individual in your life who is naturally comforting. When you don't get a job you wanted or have an argument with your significant other, this person is there to soothe you. She may just sit with you or she may help you put the situation in perspective, but most of all she is there to remind you that your value as a human being is not based on one event in your life. She offers acceptance and cares about your pain. She doesn't add to your upset by blaming you or telling you what you did wrong.

Self-kindness is about being that person for yourself. By realizing that the last thing you need when you've had a difficult experience is to be lectured to or criticized. Being kind to yourself helps you get through the sadness and hurt and move on.

Some individuals do not believe they deserve kindness. This may be the result of not having caregivers who were able to give consistent nurturing or of experiencing hurtful relationships with other people. Or perhaps being kind to the self is a new experience. For these individuals, self-kindness can feel foreign and uncomfortable. Though self-kindness may not seem natural for those who tend to be harsh with themselves, habits and comfort levels can change with repeated practice.

Practicing self-kindness leads to your being able to give yourself the same nurturing and emotional support that you get from that special person who is your biggest comfort. The advantage is that you can give it to yourself at any time and you don't have to worry about losing it for any reason. Giving yourself the comfort of kindness can help you build a sense of safety and security.

Nurturance by others releases chemicals that are calming and increase feelings of trust, generosity, and connectedness. Neff points out that there is good reason to believe that self-kindness has the same effect.

Recognition of our common humanity means remembering that all human beings are imperfect. This means that embarrassing moments, disappointment, shame, rejection, fear, and anger are all shared experiences. Every human being has experienced those situations and those emotions. Every human being has struggles. Remembering what we have in common helps us feel connected, a part of the whole. Seeing ourselves as alone in our struggle, believing that life is smooth and easy for others, leads to feeling alone and separate, a feeling of not belonging.

Neff points out that one of the ways people separate themselves from their common humanity is by comparing themselves to others. When you do this the success of others will lead to negative feelings about yourself instead of being happiness for the other person. Comparing is about competition rather than cooperation.

Mindfulness is accepting what is, in the moment, without judgment. Being able to see what is real and true is a critical part of coping well with intense emotions. Mindfulness will be discussed in a future post.

The benefits of self-compassion, according to Neff, include improved emotional resiliency, better ability to maintain emotional balance, better coping skills, and faster healing of emotional trauma. Self-compassion seems to be a key skill for emotionally sensitive people.

photo credit: Nutmeg Designs

February 1, 2012

Self-Compassion

Sometimes people who are emotionally sensitive are angry with themselves: angry because they feel different than other people, because they are easily hurt, and sometimes because they feel broken.

Perhaps they've heard that they are too sensitive or overreacting so often that they are angry with their sensitivity. Some emotionally sensitive individuals feel ashamed, like they are less than other people. Some are frustrated that their emotional reactions have gotten in the way of achieving their goals or have hurt relationships they valued. Sometimes there is a feeling of hopelessness and they have retreated from the world, seeing it as too painful.

The anger and shame that people sometimes feel about being emotionally sensitive adds to their suffering and their emotional pain. In addition, fearing being alone, left out or abandoned blocks the joy and pleasant experiences that might otherwise be available.

Our culture's focus on self-esteem, on being the best and/or gaining the approval of others, may add to the suffering of emotionally sensitive people. This focus encourages continual self-judgments and judgments of others. The emotionally sensitive may be particularly severe in their judgments of themselves.

Our culture's focus on self-esteem, on being the best and/or gaining the approval of others, may add to the suffering of emotionally sensitive people. This focus encourages continual self-judgments and judgments of others. The emotionally sensitive may be particularly severe in their judgments of themselves.

People judge themselves harshly for various reasons. Some have learned from critical people in their lives, internalizing the messages they received so they now say the same negative statements to themselves. They have accepted the judgments of others as the truth. Some individuals may criticize themselves because they believe it will motivate them to do better, though in fact it tends to do the opposite. Others may berate themselves as a form of protection. Maybe if they judge themselves harshly, they can avoid the condemnation of others.

Neff suggests that we stop judging and evaluating ourselves as either good or bad and treat ourselves as kindly as we would a best friend. She encourages people to stop floccinaucinihilipilification, a very long word that means the habit of estimating something as worthless.

Neff asserts that our culture's emphasis on self-esteem is part of the problem of not liking one's self. Self-esteem is all about judging, an evaluation of our worthiness, derived from being good (or not) at doing things we value. For example, self-esteem could be based on being a good cook or an athlete or a scholar.

Self-esteem can also be based on what we perceive as the view others have of us. For emotionally sensitive people in particular, this can be a trap. Given the value our culture has placed on logical thinking, many emotional sensitive people may have a history of being judged negatively for their emotional reactions. This past experience can lead them to anticipate rejection by others and perhaps even believe they've been judged when they haven't.

A focus on self-esteem can foster the belief that your value as a person depends on your experiences at any given moment. Are you successful in what you are doing right now? Are others faster than you at running? Did you get an A on your last test? Are you more or less successful than the person sitting next to you? At this moment do you sense approval by those around you? Or is a friend angry with you?

Basing your self-worth on the approval or disapproval of others or on your success or failure in the moment leads to constant ups and downs in your view of yourself. With this focus, establishing a solid identity, knowing who you are as a person, would be difficult. In addition, the joy of doing what you love could be lost. Instead of focusing on the enjoyment of running, each race would be about your value as a person. So would evenings out with friends.

When focused on your value as a person, everyday situations become tests of your worth. For example, when going out with friends,you may find yourself promising to not react emotionally, because others judge you negatively for that. Then you use every ounce of self-control you have to push down your emotions until you are safe at home. Even when you succeed, you might later go over the evening in your head, criticizing yourself for each perceived failure. Or focusing on how your friends acted or what they said, fearful they were judging you.

Neff proposes that self-compassion offers an alternative to the focus on self-esteem. Self-compassion is a form of self-acceptance and would fit in the radical acceptance choice of the four options for what you can do when you face a problem (see previous post, No Matter What the Problem, There's Only Four Things You Can Do). We'll talk more about self-compassion in upcoming posts.

photo credit: vvonstruen

photo credit: vvonstruen