Ed Gorman's Blog, page 64

November 15, 2014

This is America-You're free to buy as many copies of this as you'd like

From BookgasmRiders on the StormAuthor: Alan Cranis

Comments(0)Private Investigator Sam McCain returns in Ed Gorman’s latest novel, RIDERS ON THE STORM. Like previous titles in the McCain series, this latest takes place in the small town of Black River Falls, Iowa, in the not-too-distant past as indicated by the popular song used in the title. This time the story takes place during the Vietnam War, one of the most divisive periods in contemporary American history.

Comments(0)Private Investigator Sam McCain returns in Ed Gorman’s latest novel, RIDERS ON THE STORM. Like previous titles in the McCain series, this latest takes place in the small town of Black River Falls, Iowa, in the not-too-distant past as indicated by the popular song used in the title. This time the story takes place during the Vietnam War, one of the most divisive periods in contemporary American history.The year is 1971. Sam McCain, already a member of the National Guard, signs up for overseas duty. But a near-fatal car crash on the way to basic training lands McCain in the hospital with head injuries and a loss of memory that lasts for several months.Shortly after his release from the hospital and return to his hometown, Sam is awakened late one night and called to the home of his long-time friend, Will Cullen, who has disappeared and left behind a very worried wife. Cullen served in Vietnam, but retuned to Black River Falls a changed and broken man due to his war experiences, which included the accidental killing of a young Viet Cong girl. Still dealing with conflicted emotions, Cullen joins the Vietnam Vets Against The War, a move that puts him at odds with many of his fellow hometown vets.

One such vet is Steve Donovan, who is running for Congress. At a campaign rally Cullen approaches Donovan, his former friend, and tries to justify his anti-war actions. But the conversation quickly turns to shouting and becomes a fist-fight. The following morning, after McCain has returned from Cullen’s home, Donovan is found brutally murdered. Cullen is located not long afterwards asleep in his car, and evidence in his car immediately makes Cullen the prime suspect in Donovan’s murder.

McCain is convinced of Cullen’s innocence, but must find proof. So he investigates the murder and finds more than one person with good reason for wanting Donovan dead.

McCain’s first-person narration once again drives the story. And fans of the series will be pleased to find that neither passing time nor his recent brush with death has mellowed McCain. He’s still the same caustic but insightful observer of his hometown population and has lost none of his determination to see the investigation to its conclusive resolution.

Along the way Gorman again effectively captures the ambience of the period through many unobtrusive references to popular songs, books, movies, TV shows and even the clothing styles of the time. But the War and the way it made adversaries out of long-time friends is also part of this ambience. While McCain’s personal distaste for the Vietnam War and the politicians responsible for it is never less than subtle, he keeps his personal feelings to himself and remains objective as he searches for the killer.

What’s most impressive, however, is the remarkable economy of Gorman’s prose. In just under 200 pages (at least half the length of most recent crime novels) Gorman accurately captures all the nuances, emotions and essential back-stories of every character involved. In many instances, only a few sentences are needed to provide the reader all that is needed in order to know a character and thereby carry the narrative forward and keep the reader guessing the identity of the murderer.

Rumor has it that this is the final entry in Gorman’s song-titled series of Sam McCain mysteries. If so, Gorman concludes the series with one of its strongest, most politically charged stories, while reminding us of the joy of reading a well-written, intricately-plotted murder mystery.

Not many authors can pull off such a feat, but one as skilled and experienced as Ed Gorman certainly can. —Alan Cranis Buy it at Amazon.

Published on November 15, 2014 19:23

November 14, 2014

“’Have you ever thought about doing something serious, like detective fiction?’” Fred Zackel

“’Have you ever thought about doing something serious, like detective fiction?’”Fred Zackel

(This piece first appeared at January magazine, 23 April 1999.)

I met Ken Millar in the summer of 1975 at the Santa Barbara Writers Conference, the event that author Barnaby Conrad has so wondrously run for all these years. I went to the conference not to meet Millar (a.k.a. Ross Macdonald), but to quit writing.

I was 29 years old and was giving up. Oh, I had set off five years earlier, determined like every other writer that I was going to produce those words everyone had always been itching to read, only they didn't know it yet. In truth, I had sold nothing and I no longer believed anything would sell. But I wanted to quit on a high note, not feel like I had failed. After all, being a writer is like swimming up a waterfall. Nobody is surprised that so many can't do it; we are only surprised that some do succeed. I chose the Santa Barbara Writers Conference because it was advertised as being held on the beach at Santa Barbara, at the Miramar Hotel. The Miramar had two bars, two pools, and security guards on little golf carts that went around the bungalows at last call to make sure the drunks got back safely.

If you're going to quit writing, why not at the Miramar? Why not at the Santa Barbara Writers Conference, with its annual crowd of real writers to hobnob with? Ray Bradbury was there, as was Alex Haley, who was then finishing up Roots, and Irwin Shaw, who was now a Rich Man and not a Poor Man, and Maya Angelou and Gay Talese and Charles Schultz and... and Ross Macdonald.

I had admired Ross Macdonald for his work for years. I can remember the day a college roommate gave me his copy of The Chill and dared me to read a mystery. I read it in a single sitting and was blown away by the intellect that could conceive such a lucid pathway through the maze of human deviousness.

I was a fan. That was enough.

And I saw him there at the conference. Ross Macdonald was tall and stately, stoic and gentlemanly. He wore a straw hat; Santa Barbara was hot that summer. He had buttoned the top button of his short-sleeve shirt; he was elderly. He walked deliberately. He looked unapproachable. Until I saw him with other people. His smile was open and flashing; he was generous with his smiles.

I didn't try to approach him. He was a published novelist. I was from the other side of the universe. The unknown side of that side. Whatever thoughts I had ever had about being a writer -- hell, I was there because I was quitting writing. That anguish was for other people. I didn't feel bad that I wasn't cut out to be a writer, that I had wasted a few years of my life. Hey, I was a child of the 1960s. No loss there.

One or two days before the conference ended, I got the word from Barnaby Conrad's people that every "student" at the conference was supposed to submit some work they had done. Well, I had nothing substantial with me. Certainly nothing I wanted to show anyone. I hadn't brought any completed stories, any polished poems, anything. What I had were pages of dead-ends, cul-de-sacs of unfinished stories: Evidence I might need to keep my resolve if I lost my courage and thought about giving the writing life another try. For some reason -- maybe my latent fear of authority figures -- I looked in the small notebook I always carried to see if there were any miracles I had mislaid. The notebook wasn't much. Inside were a bunch of observations about the nightlife in San Francisco, where I was then living. I had a job as a cab driver; I saw things I never wanted to see. What was written in there were things I didn't want to forget. But no prose pieces. Not even a plot. Not enough for a character sketch. Just a bunch of one-liners about the streets of San Francisco after midnight.

I could remember my college professor whispering, "If you call it a poem, it's a poem." So I took two dozen of these one-liners and stretched them into a free-form poem, borrowed somebody's typewriter, submitted the poem, and promptly forgot about it.

The next morning, someone -- I still don't know who -- telephoned my bungalow and said I had to get up, it was 8 a.m., and I had to get over to the convention center. Well, if you wake me up by screaming at me, I get up and never wonder why. Especially when I'd been present at last call the night before, and looked it.

Everybody was in the convention center. Somebody was announcing the winner of the "poetry contest." And it was me!

Somebody said I had to come up on stage and read my poem. Somehow I did it. The only face I saw was Ross Macdonald's, and he was staring so intently, I got scared and wished I were elsewhere. I didn't figure he was buffaloed by my poem. I figured I won the poetry prize because everybody else there wrote fiction.

By 8:30, I was on a stool in the Miramar bar. I was alone.

Ross Macdonald looked in the bar. I was impressed. This was the closest I had gotten to him in six, seven days. I toasted him with my draft beer, and he came over. He stuck out his hand and I shook it, and he said, "That was a very nice poem you wrote." I was stunned. When I'm stunned, I get as charming as I can be. "Can I buy you a drink?" He scowled and said, "I don't drink before sundown." Oh.

Then he left.

While I didn't think I had blown it, I didn't think I had made a very good impression on the writer I most looked up to. But I knew I was just a fan, and he would forget me quickly enough. There's always salvation in anonymity.

Twenty-four hours later, on the last morning of the conference, I was in the bar again, nursing another of those a.m. drafts, and Ross Macdonald stuck his head in the bar again. He saw me and came over.

"You look down in the dumps," he said.

"I have to fly back to San Francisco. My plane leaves in four hours. I have no place to go before then, so I'm just sitting here in the bar at the Miramar."

He frowned, almost said something, then made up his mind. "Do you need a ride to the airport?"

"Thank you, sir, but not for four hours."

Ross Macdonald said, "Why don't you come up to my house for the next four hours, and then I'll give you a ride to the airport?"

I think I said yes.

I know I followed him out of the Miramar bar, my suitcase in hand. We walked about a hundred yards to the parking spaces on the road into the Miramar. Two elderly women were there, standing by a compact car.

Ross Macdonald announced to them, "This is Fred Zackel, who wrote that poem about San Francisco. His flight there leaves in four hours, and he's having difficulty getting out to the airport."

Then he introduced me to his wife, the mystery writer Margaret Millar and the other woman with her. "He's on the same flight you are," he told the other woman.

He told them I could hang with them, and we could all go to the airport together. The two women weren't happy with his generosity, but we all piled into the car. His wife sat behind the wheel, while Ross Macdonald sat beside her. I sat in the back seat. Next to author Eudora Welty.

* * *

Margaret Millar drove like a bat out of hell. She drove a tiny Japanese car, one of those early models that barely held four adults. And she went around curves like the chase at the end of a thriller, and more often than not jumped the curb doing so. She never slowed, either. She went full-bore and flat out. She scared me the most when we swung by the Santa Barbara fairgrounds. Honest to God, I didn't think she'd be able to pass a truck changing lanes on the inside before he, too, filled the lane she wanted. But she did it, squeezing through like a teenager in a crowd. Ross Macdonald sat beside her. I sat behind him, and Eudora Welty sat on my left. I felt so sorry for her. Every time Margaret Millar took a turn, either Eudora Welty smashed into my shoulder, or I would crash into hers. Eudora Welty was not a small woman, but she did appear delicate and fragile. Banging into me must have jarred her as much as getting smacked with a swinging door. And every time I flew into her, I nearly squashed her like a bug. We had no seatbelts in those days. And nobody said a word the entire way. The trip to Santa Barbara's exclusive Hope Ranch neighborhood was over quicker than it should have been. We all went inside the Millars' ranch-style house on Esperanza Avenue, the one they had bought with movie money. The Millars had dogs -- great German shepherds, for the most part -- and like all true dog lovers, they kept the house safe for galloping hounds. After the handful of dogs told us all how grateful they were to see us, Margaret Millar let them out. Over instant coffee I was quizzed about my past, present, and future.Being quizzed was a terrifying experience. These three writers were brilliant, famous, and successful. I was not. I felt very much out of my league. I tugged out a cigarette. "Do you mind if I smoke?" All three faces lit up with disapproval. "No one smokes inside the house," Ross Macdonald said. "Mind if I smoke outside?" I went poolside and lit a cigarette. I stayed outside longer than I should have. I felt defiant. I had nothing to lose, I thought. Back inside, the quizzing began again. "I came to the writers conference to quit being a writer," I explained. "In the past five years, I have sold nothing, and I don't believe anything will ever sell." The three looked at me as if I was a talking dolphin. "Why go to a writers conference to quit writing?" "I wanted to go out with no regrets. The Miramar Hotel is on the beach in Santa Barbara, has two pools and two bars, and the security guards drive around after last call in golf carts to pick up the drunks and make sure they get back to their cottages." "Read your poem for us," Ross Macdonald said. I took it from my binder and read it aloud. All three leaned back and contemplated the cosmos. When I was done, all three looked at each other and frowned. "What kind of writing have you been doing?" Macdonald asked me. I said I had been trying to write literary fiction about Midwest farm towns. About people as gray as a winter's sky and hearts as cold as a coffin's touch. About being a stranger in my native land. You know, tedious crap. "May we see some of it?" I went to my suitcase and unpacked the chunks of paper. Each writer took a swatch and read. Then they passed the papers around. I drank black coffee and watched them read. When they were done, all three gave me back my manuscripts, stared at the floor and frowned. Finally, Ross Macdonald spoke. "Have you ever thought about doing something serious, like detective fiction?" I said, "No." In a panic, I said, "I don't know how." He said, "I will help you." Three of us stared at him.

* * *

Published on November 14, 2014 18:23

My first novel: Robert J. Randisi

MY FIRST NOVEL: ROBERT J. RANDISI

This is the story of how my first 4-book series became my first novel. I joined the Mystery Writers of America in 1975. I was 24 years old, had met some authors in ’73 in Boston at my first Bouchercon, before I published my first story. My second Bouchercon was Chicago in '75, where I met Max Allan Collins, Percy Parker, Robert Edward Eckels and a few others. By then I had sold my first short story, but had not yet joined MWA. For some reason I had decided not to join on the strength of a single short story sale, but the writers at that ’75 Bouchercon all advised me otherwise. So when I got back home, I joined. From that point on I rubbed shoulders with other writers twice a month, at a cocktail party and a dinner. But the thing about those gatherings is that they didn’t only attract writers. There were also agents and editors.I was shy back then, believe it or not. Stand-in-the-corner-with-a-drink-in-my-hand shy. But to overcome that shyness I decided to tend bar at the cocktail parties. That way, everybody in the room had to come to me. I tended bar up there for a few years of those parties, and that’s where I met my first editor.We became friends. We had lunch in the city. We had drinks together. We both did some work in The Mysterious Bookshop when Otto Penzler first opened, to help out. It was the kind of networking that doesn’t happen in publishing today. Who needs to wine-and-dine an editor—or vice-versa—when you can use your disposable income to publish your own books. (But that’s a rant for another time).And then I showed him a proposal for a series about a private eye who works for the (fictional) New York State Thoroughbred Racing Club. He wanted to buy 4 books. That was the plan. Up to that point I had published 6 short stories in Alfred Hitchcock and Mike Shayne’s Mystery Magazines, and some lesser reputable but better paying work in Beaver Magazine. I was excited. A 4-book private eye series about horse racing. Hell, I was gonna be the American Dick Francis!But there’s always a monkey wrench in the works, isn’t there?I was about to get a contract when the editor called to tell me the publisher had frozen his buying. “We just have to wait about six months,” he said. And then six more.Finally, we struck a plan. He’d buy one book. Then another, then a third, and so forth. That way, the publisher would never catch on.So I signed a contract to write THE DISAPPEARANCE OF PENNY, the first Henry Po book.But before I signed it, since I didn’t have an agent, the editor told me to close the door to his office, and he went through the contract with me, page-by-page. It was the first and last time an editor ever did that for me.THE DISAPPEARANCE OF PENNY was based on a short story of the same title that appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine in 1976. In the story the P.I.,’s name was “Frank Tucker.” For the book he became “Henry Po.” The book was published in Sept. 1980. There was never another Po book. There were, however, about half a dozen short stories over the years. But that 4-book series never materialized. I did, however, get a contract to write and create a western series, which became THE GUNSMITH.But that’s another genre, and a story for another time.

Published on November 14, 2014 07:34

November 13, 2014

John Lutz: My First Novel

By– John Lutz

My first novel didn’t sell. And I was pretty sure it wasn’t going to. Several publishing houses had marked the ms with suggestions, coffee stains, spittle… No one proffered a check.

My second novel, THE TRUTH OF THE MATTER, the first one that sold, was a different story (which helped it immensely) and as I recall, it sold pretty fast, and was published as a pb original by Pocket Books. From then on I had good luck.

I was inspired to write this novel by two writers at opposite ends of the continent (I was in the middle and still am), Barry Malzberg and Bill Pronzini. Barry at the time was working for an agent, as was Bill. It was at their suggestion that I attempted another ‘first’ novel. They talked me into it, furnished encouragement and sound advice, and for that I remain grateful.

I didn’t have to look hard for subject matter. Read on and you’ll understand why. We’ll call him Sam. He was a nice guy and the most inventive and imaginative congenital liar I have ever met. That was because it was obvious that he believed every word of his lies. I mean he believed!Sam could speak solemnly about being a champion bronco buster, a close friend of the Dalai Lama, flying missions as Ted Williams’ wing man in Korea, swimming the Rhine River with his friend Patton to show Ike it could be done, living secretly on nothing but apples in a Munich basement after being shot down in a B17, where he counted German troop movements and passed info to the Allies. And on and on… It didn’t happen often, but when he was backed into a corner and was irrefutably wrong, he would refute.

The thing was, I found out that some it was true. This was, despite his world of fabrication, a man of substance. He didn’t need those lies, and yet he told them, even to himself. He would surely pass a polygraph test.

So I asked myself, what would happen if a Sam was convinced that he’d killed someone? If, while he was running from the law, he little by little came to realize that no one was chasing. Yet still, for his own illogical reasons, he had to keep running.

So I sat down and wrote THE TRUTH OF THE MATTER. But it was all lies.

John Lutz

Published on November 13, 2014 13:59

Donald Westlake's stepddughter has been found

bypewestlake

A Sad and Sadly Real MysteryOctober 25, 2014 in Personal by pewestlakeAunt Katharine with her newest niece, Maddie.Update:Katharine Adams has been found safe in New York City. She has been reunited with her family. Thank you for all the support over the past few weeks. This post will be deleted and normal business will resume within a few days.***

Published on November 13, 2014 11:21

November 12, 2014

My first novel: James Reasoner

Some of you know that my first novel was TEXAS WIND, and that's true as far as it goes. TEXAS WIND was the first novel I finished, and the first novel of mine that was published.

But it wasn't the first novel I started.

As 1978 rolled around, I had been selling short stories for a little more than a year: mysteries to MIKE SHAYNE MYSTERY MAGAZINE and men's magazine stories (basically sex stories, some with a crime or mystery angle thrown in) to several different markets. I hadn't made much money yet, but by golly, I was a professional writer.

As such, I bought the big WRITERS MARKET volume published every year by Writers Digest, and I would sit and comb through its pages for every potential paying market I could find. Since I'd started out writing short stories, as many people do, that's what I concentrated on, but I began to get the idea that I ever wanted to make a living writing (which I certainly did) I was going to have to start writing novels, too.

That still seemed like a pretty daunting task. At this point I hadn't started writing the Mike Shayne novellas in MSMM. The biggest thing I'd done was a 10,000 word private eye yarn that failed to sell. So the idea of writing a 60,000 word novel just seemed like more than I could tackle.

So as I'm going through WRITERS MARKET I come across a listing for a publisher in San Diego that's looking for erotic novels. Some of you know the publisher I'm talking about. The company published a dozen or so novels each month (some of which were retitled and re-bylined reprints, I suspect now), so they needed material. They wanted 35,000 word manuscripts, for which they paid the princely sum of $400.

In 1978, 400 bucks would buy a considerable amount of groceries for a young couple, and hey, 35,000 words was a lot but it seemed like a book of that length might be within my reach. And at least the pay was a little better than the penny-a-word (or less) I'd been getting for short stories. I was already writing sex stories for magazines. Surely I could write a novel in the same vein.

Now, as a young guy growing up in the Sixties, I'd read porn novels occasionally, of course, but not with an eye toward ever writing them. I figured I'd better study up on the market. So I went to a newsstand in Fort Worth that sold books from the publisher I'd set my sights on, and I bought several of them. I wasn't joking when I said I planned to study them. I read every one pretty closely, making notes about the characters involved and breaking down the plots into chapter-by-chapter outlines so I'd be familiar with the formula used in the books. Once I had done that, I came up with characters of my own, wrote an outline, and sat down to write the actual book.

A week or so and 30 or 40 pages later, I looked at the stack of typing paper that had built up and said, "Nope." I put the book aside and never went back to it.

That decision had nothing to do with any sort of moral judgment—I'd written sex fiction before and would continue to do so as short stories—but rather a feeling that, hey, a writer only gets one first novel, and I wanted mine to be something else. I had set out a couple of years earlier to be a private eye writer, so I decided to cling stubbornly to that goal.

Right about then fate, in the person of Sam Merwin Jr., stepped in. Sam, the editor of MSMM, had become a friend and mentor, and he asked me to write one of the Mike Shayne novellas for the magazine. 20,000 words for "a flat, lousy 300 bucks", as Sam phrased it in his letter.

Heck, that was even better than what the porn novel would have paid. I told Sam I'd love to write a Mike Shayne story, he sent me the series bible, and a couple of weeks later I had "Death in Xanadu" ready to send to him. That experience convinced me more than ever that I needed to write a private eye novel.

I wanted it to be set in Fort Worth. I didn't know nearly enough about New York or Los Angeles or San Francisco to write a novel set in any of those places, even though the classic PI novels I'd grown up reading were set there. Why not Fort Worth? There were private detectives in Texas, weren't there?

So in October 1978, writing with a fountain pen in a spiral notebook like the ones I'd carried in high school ten years earlier, I began writing TEXAS WIND. I was working for my dad at the time, managing the office of his TV and appliance sales and service business, so I wrote nearly the entire book sitting at the desk in that office, scribbling a paragraph and then answering the phone, writing another paragraph or two and then helping a customer carry in a TV that wasn't working, doing another few paragraphs and then adjusting the horizontal or vertical hold—or both—that another customer had gotten 'way out of whack on their set, writing another paragraph and then taking the back off a set with sound but no picture, pulling the cap off the horizontal output tube, plugging the set in with a cheater cord and checking for arc, replacing the tube if it was bad, writing up the bill, carrying out the set, then back to the desk for another paragraph...

I tell you, it's a wonder that book makes any sense at all.

When the handwritten first draft was finished, I typed a second draft, revising as I went along, then made notes on that second draft. Livia worked from it to type a clean submission draft. Early in 1979, the book was finished and ready to go. But we didn't have a carbon copy—I always hated carbon paper and hardly ever used it—so we gathered up a bagful of dimes and nickels and took it and the manuscript to the Thrifty Drug Store in the Monnigs Oaks Shopping Center in River Oaks (the suburb of Fort Worth, not the one in Houston) where there was a coin-operated copy machine and stood there feeding coins into the thing as we copied the entire manuscript page by page. We kept that, and the original Livia had typed was our submission copy.

Boy, did we submit it. I hauled out the ol' WRITERS MARKET book again and sent the manuscript to every publisher that did mysteries and some that didn't. Back it came, usually pretty quickly. Finally I sent the manuscript to Manor Books. I didn't know anything about them other than the fact that I'd seen a few of their books around and they were in New York, which was where all the real publishers were, right?

At the time we didn't have a mailbox at our house, so we got all our mail at the post office in the little town where we lived. Since I got manuscripts back in the proverbial SASEs pretty regularly, I didn't want them rolled up and stuffed into a small box, so we rented a drawer—P.O. Drawer C, our address for a number of years. A couple of weeks after sending the manuscript of TEXAS WIND to Manor, I opened the drawer at the post office one morning on my way to work, and there was a large manila envelope in it from Manor Books. I could tell right away that it wasn't the manuscript being returned. Could it be...could it actually be...a contract?

It was. An absolutely terrible contract that offered a pittance of an advance and was set up so that Manor wouldn't have to pay me royalties until hell not only froze over but stayed below freezing for a month. Nobody in his right mind would have signed such a contract.

But they were offering to publish my book! It would be an actual printed book that people could walk into a store and buy! I would be a published novelist!

Of course I signed the contract. That day. And it went back to New York in that afternoon's mail.

Financially, the deal worked out every bit as badly as you might expect. Clearly, the folks at Manor never had any intention of paying me anything, not even the pitiful advance they'd offered. But a year or so later I got a box of author copies, and seeing that book with its awful recycled cover and its pages printed on the cheapest paper possible is still one of the highlights of my life. It was my foot in the door, and more than 300 novels later I'm still at it. Would I have gone on to that career if my first novel had been about horny cheerleaders instead of a world-weary Texas private eye? We'll never know.

Published on November 12, 2014 16:14

Interview: Gary Disher with Ben Boulden Gravetapping

Mr Disher is also the writer of a series of police procedural novels featuring Hal Challis and Ellen Destry. The first title, The Dragon Man, appeared in 1999 and the latest, Whispering Death, was published in 2011. The fourth novel in the series, Chain of Evidence, won the Ned Kelly Award for Best Fiction, and was named by Kirkus Reviews in its Best Books of 2007 (Indie Books category).

His most recent crime novel is the excellent Hell to Pay(published as Bitter Wash Road in Australia) featuring a, so far, non-series police constable nicknamed Hirsch stationed in a small South Australia bush town. Mr Disher was kind enough, and showed an amazing amount of patience, to answer a few questions. The questions are italicized.

In the United States you are most well known as a crime novelist, but you also write children’s and adult literature. Is one type of fiction more difficult to write, and do you have a favorite?

I don’t have a favourite, all three satisfy me creatively and offer the same creative challenges. It’s assumed that writing for children and teens is simplistic and therefore easy work, but the reverse is true. Perhaps I have tested my creative boundaries with the ‘literary’ fiction, but I take care with the craft aspects whatever I write. However, I’d argue that writing crime fiction has taught me an enormous amount about creating and maintaining tension and suspense, which has helped with my children’s/YA and general fiction writing.

I read that you received a creative-writing fellowship to Stanford University in California. When did you attend Stanford, and was it a positive experience? Also, as a fan (it’s an imperative since I’m from Utah) I must to ask, did you meet Wallace Stegner while studying at Stanford?

The Australian Stanford writing scholarship was set up by a wealthy Australian who had studied at Stanford. It no longer exists, but for many years the scholarship would go to a poet one year, a fiction writer the next. I value my time at Stanford very highly. The scholarship came at just the right time, when I’d had some success with short stories in little magazines and competitions, but yet knew nothing about the craft of writing. By the end of my time there, I had a clearer grasp of fiction writing techniques, saving me years of hit-and-miss writing, and, more importantly, knew how to edit and rewrite my work. Yes, we (my class of twelve fiction-writing students) did meet Stegner one afternoon. A very genial, knowledgeable and gracious man.

In an interview I read that you enjoy watching “crap American crime shows on TV.” A habit we share. What are some of your favorite television shows?

I have corrupted my daughter into watching with me: anything from Justified, Dexter and Breaking Bad (incidentally, these are classy, not crap) to CSI Miamirepeats and Criminal Minds, which are crap. In fact, one tires of crap TV quickly: the absurd plots, the bad acting and the aridity of formulaic writing. I should also mention some of the British shows, like Scott & Bailey and Prime Suspect, and the Scandinavian shows, like The Killingand The Bridge (the US version of The Bridge was terrific).

Speaking of television, Internet Movie Database (IMDb) identifies five television films, featuring a detective named Cody, based on characters created by “Garry Disher.” Are these films based on your work? If so, did you develop the characters for television, or are they based on your fiction?

Many years ago, after the first three or four Wyatt novels had appeared, I was approached by the Sydney producer of a water-police series to create a new character for a series of two-hour tele-movies. They paid me enough to clear my mortgage, but… First, I created an undercover policeman, having met one recently and been struck by the strange double-life he’d led, infiltrating biker gangs (and the fear and the ambiguity), but learnt to my cost the producer had a certain happy-go-lucky, cheeky-grin, surfer dude actorin mind (“He can’t do dark,” they told me). So back to the drawing board. I later went on to write three storylines for the scriptwriter, about a cheeky-grin cop named Cody… One story involved art theft. The producer told me, “We see our audience as the western suburbs [i.e., blue collar workers] of Sydney: they’re not interested in art theft.” That was my introduction to the world of writing for film and TV.

In an interview for the State Library of Victoria you said, “A good crime novel tells us about the world we live in. Tells us about human nature. In many ways literary fiction has let us down on that front.” Would you expand on this idea? Why do you think current literary fiction is failing?

I feel sometimes when I read the latest highly-praised literary novel that it’s rich in characterization and absorbing themes and gorgeous language, but I’m dying for something to happen, for a character to do something (walk through the door with a gun in his hand…?). At the same time, these novels may go deeply into characterization and relationships, but exist in a kind of vacuum when it comes to the world surrounding the characters—the world of tension between rich and poor, of the stranglehold of fundamentalist thought in public debate, of corruption in government and business, of everyday racism, sexism and homophobia. Crime novels tackle these things.

In this same interview you said, “Reading is vital to me as a writer.” You further said you tend to read bad books critically, but you read good books for pleasure. When you read a bad book do you look for what doesn’t work, and learn from it? As a writer do you learn more from a good book, or a bad one?

Yes, I do look for what makes a bad book bad. It hones my critical editing abilities, which I hope helps me look for what is weak or poorly thought out or badly expressed in my own writing. Good fiction will also help, for I might see how other writers solve certain technical problems (I learnt how to handle an ensemble cast by reading John Harvey’s Inspector Resnick novels, for example).

You have two current series characters: Hal Challis and Wyatt. Each is very different from the other. One (Challis) a career police inspector, and the other (Wyatt) a career criminal. The Challis novels are police procedurals written with deliberate style and pacing—the crime is often revealed in stages, and never rushed—and the Wyatt novels are stark, and somewhere near hardboiled. Do you enjoy writing one over the other, and does each style demand different writing (maybe craft) approaches?

I wrote the Challis and Destry novels as a change from writing the Wyatts (six in six years, at the start). The Wyatt novels follow a certain formula (Wyatt identifies a place to rob, robs it, is betrayed, gets his revenge), but that doesn’t mean they’re easier to write. I’m a planner, spending weeks on a plan before I start, and every book poses challenges (balancing character and plot, whilst listening to my instincts). In both series, I take the reader into the minds of the bad guys as well as the good (it’s great for creating tension if the reader knows more about a situation than the hero does), so my thinking processes are similar. The book that posed the greatest challenge is my latest, Bitter Wash Road(unfortunately titled Hell to Pay in the States) for I do not stray from the thoughts, hopes and fears of the main character.

I agree. Bitter Wash Road is a much better title than Hell to Pay. It features a very likable protagonist named Hirsch. Can we plan on seeing him again?

I have been making occasional notes for a follow-up Hirsch novel but nothing definite or any time soon.

Your novels, particularly the Hal Challis police procedurals, have a very strong sense of place. As an example, in the first Hall Challis novel, The Dragon Man, you describe the heavy heat of mid-summer, Challis showering with a bucket to capture excess water for use in the garden, herons feasting on mosquitoes, etc. What is your expectation for setting within a story, and how do you deal with it as a storyteller?

I know from teaching writing that beginner writers take the setting for granted. “Two characters are having an argument in a sitting room: okay, there’s a TV set, a couple of armchairs, a bookcase, that will do.” It won’t do. The setting is vital. If handled carefully (certain objects highlighted, or described in a certain way, appealing to the reader’s sense of touch, taste, smell, sight and hearing), a setting can come alive, seem tangible, and say something about the characters and the atmosphere.

Hal Challis, especially in the early novels, is something of a broken man. In The Dragon Man you introduce the backstory of his wife, her affair, and the attempt she and her lover made to kill Challis. This is juxtaposed with Hal’s efforts to rebuild an old de Havilland Dragon Rapide airplane. Did you intend this to be an image of destruction and renewal? Or did you have something else in mind?

I simply wanted to show a shy, somewhat sad, careful man with an interest that would absorb him, after his recent heartache. Plus, I love old planes.

Staying with Hal Challis, I recently read the latest novel, Whispering Death, and I was struck that the cycle may be at an end. He sells his car—a now unreliable Triumph—and the Dragon Rapide he has restored over the previous novels. Not to mention he is involved with Ellen Destry and his life seems to be quite nice. Is this the final Hal Challis novel?

Refer to the question above. It’s not the latest Challis, for I’m halfway through a new one. But I like to keep the series fresh for me as a writer and fresh for the reader, and so the characters change over time (marriage, job-rank, place of domicile, etc., etc.). I couldn’t see where the plane-restoration theme could continue, so found a way of jettisoning it for the future. So, yes, a cycle has finished, but not the series.

Whispering Death also featured an enjoyable Wyatt-like—professional criminal—called Grace. She is a thief who is running from more than just the police, and there is a hint that we may see more of her. Something I would very much enjoy. Do you have plans for Grace in future stories, maybe even one of her own?

I loved creating Grace. She’s whispering in my ear about a job she’d like to pull (I just have to think who her nemesis could be).

Your Wyatt novels have been favorably compared with Donald Westlake’s, as by Richard Stark, Parker novels. There are similarities, but there are also significant differences. The most obvious is, Wyatt, while controlled, is more emotional than Parker, and even remorseful of the consequences of his actions. When you set out to write the Wyatt novels had you read any of the Parker novels? Were you influenced by the Richard Stark novels?

I was greatly influenced by the Parker novels. But I had to make Wyatt my own character, not a clone of Parker. So now and then we see a little way into Wyatt’s inner life—but I don’t want to take this too far. If we cared too much for him (he had an unhappy childhood or he robs banks to pay for his little niece’s leukemia operation), he’d be less forceful and compelling. He’d no longer be Wyatt.

After a 13 year hiatus (1997 to 2010) you wrote the seventh Wyatt novel in the self-titled Wyatt. Can we look forward to another Wyatt novel in the future?

The new Wyatt, #8, is coming out in Australia late 2015. The Australian title is Down to Dust, and I hope my US publisher, Soho, picks it up.

A superficial question. The novel Wyatt is billed by Soho as a “Wyatt Wareen novel.” Is this actually Wyatt’s last name?

I have no idea where the name Wareen comes from. I have never used it. The character has always simply been called Wyatt. I have a vague idea that a reviewer some years ago called him Wyatt Wareen, but where he got the name, I have no idea.

I heard this question in an interview on a BBC program a few years ago. If you were stranded on an island and you had only one book. What would it be?

I think a big fat, well-illustrated history of art. It would be instructive and nourish the imagination.

The opposite side of the coin. If you were allowed only to recommend one of your novels, or stories, which one would you want people to read?

It’s always the latest one: Hell to Pay (titled Bitter Wash Road in Australia)

Lastly, as we discussed earlier, you are an avid reader. Do you have any particular favorite writers—in any genre, including literature—that have influenced you the most as both a writer and a man? Are there any Australian writers you would like to mention?

Among Australian writers, Peter Temple is peerless (crime), and so is Helen Garner (‘literary’ true crime, as well as literary fiction). For her short stories, the Canadian, Alice Munro. In terms of crime writing influence, I’ll name John Sandford. He’s a very tricky and sneaky plotter, and clearly loves creating his bad guys. In terms of prose style, Richard Ford and Raymond Carver, both of whom I met when they visited Australia.

You are subscribed to email updates from Gravetapping

You are subscribed to email updates from Gravetapping

Published on November 12, 2014 07:03

November 11, 2014

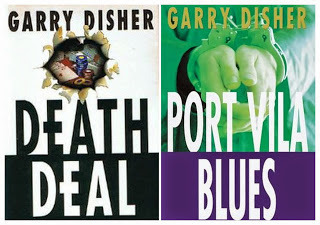

Gravetapping/Ben Boulden The Invisible Plague by Jack Bickham

Davey Clock is a professor of College English, specializing in Shakespeare, at a small Midwest university. He is middle age, overweight, divorced, a pacifist, and something of a coward. At the end of summer term he makes a late night trip to his campus office. The tropical fish he keeps in his office need attention, a pile of papers await grading before his summer break can begin; which includes a week of vacation in his favorite city, San Francisco, and another of research in Guatemala City.

The harsh sound of a fire alarm in the Microbiology building interrupts his night. After calling the fire department he wanders over for a closer look. He is rewarded with a blackjack to the back of the skull when he offers help to a man exiting the building in a rush. When he awakens in hospital he finds himself in the middle of an investigation by a shadowy government agency—a deadly toxin was stolen and the professor developing it was killed. A situation Davey likes even less than the ache in his head.

The Invisible Plague is a slick, linear thriller. It is quick, stark, and very much of its era—government mistrust, war weary, and cynical. Cynical in both the government’s treatment of Davey, and Davey’s reaction to that treatment. Davey Clock is painted as something of a Hamlet—indecisive with an early lack of personal courage. He also has an annoying habit of quoting Shakespeare in everyday conversation, and a certain self-righteousness (particularly early in the novel) that is barely contained.

The plot is designed in a simple, but effective, three act format. In the first act Davey is introduced, as is the primary confrontation—the robbers, and to a lesser extent the government agents. The second act is comprised of Davey’s attempts to deal with both, and the third, executed very well, is the climax, which includes both a satisfactory conclusion, and something of a redemption for Davey.

The Invisible Plague is an entertaining novel. It appears its distribution was limited—I have been looking for Jack Bickham titles for 20 years and have seen it only on the Internet—but it is worth a look if you enjoy the older style thriller in general, and the work of Jack Bickham in particular. It reminded me a little, although not quite as good, as Dean Koontz’s (as by K. R. Dwyer)Dragonfly.

Published on November 11, 2014 11:20

November 10, 2014

From Brash Books MICHIGAN ROLL: FOR FANS OF ELMORE LEONARD

11.10.14 MICHIGAN ROLL: FOR FANS OF ELMORE LEONARDWritten byBrash AdminShare on facebookShare on twitterShare on emailShare on pinterest_share

Novelist James L. Thane, author of No Place to Die and Until Death, shares his fondness for Tom Kakonis’ thriller Michigan Roll

Timothy Waverly’s business card describes him as an “Applied Probabilities Analyst,” which is Waverly’s idea of a little joke. Timothy is an ex-con out of Michigan who now makes his living in south Florida as a professional gambler, trimming the doctors, dentists and others who search out a little high-stakes action while on their Florida vacations.Waverly did a stretch for accidentally killing his ex-wife’s lawyer. The ex-wife is now remarried and living in Traverse City, Michigan, with the young son that Waverly never had a chance to know. Restless, and anxious to get out of the hot Florida sun for a while, Waverly decides to take a little vacation to Traverse City, which is a small resort community. He has no well-formulated plans; maybe he’ll attempt to see his son and maybe he won’t.Meanwhile, in Traverse City, an amazingly stupid college kid named Clay Clemmons, has attempted to screw over some major drug dealers by ripping off $500,000 worth of their cocaine. Not surprisingly, the drug dealers want it back, and Clemmons, who is quickly in over his head and who has all the backbone of a chocolate éclair, calls his sister in Chicago and pleads with her to come up and somehow bail him out of this mess.The sister, Holly, is a stunner, and she should have sense enough to tell her brother to deal with his own messes. But she’s been cleaning up after her little half-brother for so long now that it seems like second nature. So she pops into her Porsche and tools on up to Traverse City. By the time she gets there, however, things have gone from bad to worse. The drug kingpin has dispatched two particularly nasty creeps to deal with Clay, and he is now in hiding. Neither the creeps nor his sister can find him.The creeps can’t find Clay, but they do find Holly and attack her in a parking lot in an effort to make her give up her brother. Enter Timothy Waverly at exactly the opportune moment. He rescues Holly and in short order is caught up in the middle of this whole mess.What follows is an entertaining story that will remind some readers of an Elmore Leonard novel. The characters are quirky and interesting; the plot moves along at just the right pace, and Timothy Waverly is a very engaging protagonist. The book should appeal to any reader who enjoys Elmore Leonard and is looking for something similar.Tags: crime novel, Elmore Leonard, James L. Thane, Michigan Roll, thriller, Tom Kakonis

Published on November 10, 2014 14:19

Hardboiled Monday: Quarry

Hardboiled Monday: QuarryPosted by Howard on Monday, November 3, 2014 · Howard Andrew Jones

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details and the list are here. And earlier discussions are here.Today we’re looking at one of the book seres by famed mystery and suspense writer Max Allan Collins, Quarry.Chris: Although Collins once wrote me that the Nate Heller series was his most significant work, I still prefer Quarry. The early novels about this dark protagonist translated the day-to-day reality of the 1970s into lucid, matter-of-fact prose in the same fashion that Gold Medal Originals often did for the 1950s.More to the point, Quarry is a top drawer anti-hero, a remorseless hitman who often finds himself pitting his lethal skills against characters more reprehensible, if ultimately not quite as dangerous, as he is. Leavened with plentiful black humor, casual sexuality, and sharp blasts of abrupt violence, these novels read with great speed and often feature endings with an extra wicked twist.I confess a peculiar fondness for stories in which the protagonist is a dangerous, scurvy bastard pitted against characters who are even worse. Maybe it’s because my Dad took me to see Fistful of Dollars when I was seven. In any case I was pleased when Collins began producing new Quarry novels in 2006 (the first four appeared in 1976 and ’77). The eleventh Quarry novel, Quarry’s Choice, is set to appear in January, 2015, from Hard Case Crime. I predict that I will buy it (as usual), vow to save and savor it (as usual) then read it as quickly as possible at the very first opportunity (as usual).Howard: Technically my interest in Quarry pre-dates the creation of the list. Like the Westlake/Stark Parker books, if I wasn’t already reading them, Chris would have slipped them into the master list because they’re top notch. They’re actually the second set of hardboiled books I read. I’d finally gotten around to trying the Parker series, devouring it while I was laid up after a knee surgery, and I called Hocking to ask if there was anything with the same tone and of similar quality.“Well,” he said, “there is one thing that’s like it in a way…” He was right. When I first started reading Collins I wrote that he was: “impressing me more and more, sort of the way Donald Westlake/Richard Stark did, in that the more I read of his work the more I come to appreciate how finely tuned the engines are in what seem, upon first glance, pretty simple vehicles. They’re not really simple at all, no more than a still life by a master painter is simply a snapshot of a bowl of fruit.”The overt sexuality and the first person narration — which allows you a good look into the mind of Collins’ protagonist — makes Quarry novels different from the Parker books, as does Quarry’s profession, but the skillful variation on the theme and the capable, compelling way that Collins interests you in what happens to a character you probably shouldn’t be rooting for has a lot in common with what Stark did with Parker.Odd as it may seem, despite the fact that Quarry is a hired killer you find yourself liking the guy. He tips well and sympathizes for the plight of the working man. He likes good genre books (like Leonard’s Valdez is Coming ). In a lot of ways he’s an opened-minded guy and is quite relatable. Except for, you know, brutally eliminating humans without remorse. He questions sometimes, sure, but he feels no remorse.Chris: It did occur to me that some readers might find the Quarry novels were not to their taste. Their unreconstructed, old school manly narrator may rub some the wrong way, as might the relaxed 1970s style sexuality, or Quarry’s equally matter-of-fact willingness to kill people.The books first made their appearance in the era of “Men’s Action Adventure” novels, and sat on shelves not far from The Executioner, The Death Merchant and umpteen other lethal, masculine heroes. But while Quarry may share some of the basic attributes of these characters, his adventures bring something more to the reader, something richer and somewhat paradoxical.The best Quarry novels have a powerful noir surge.The second book, Quarry’s List , may not be the finest in the series, but it ends with a dizzyingly dark twist in which the narrator performs what I can only describe as a cruelly violent act of mercy and kindness.Given this noir element it’s striking that the books consistently feature a steady stream of black humor. Sometimes the humor is understated, sometimes in-your-face, but it gives the series a wry, self-aware sensibility.This combination of grim noir and black humor suffuses fast-moving plots awash with violent action, sex, mystery, intrigue, and double-dealing, creating some pretty distinctive entertainment. Not for everybody, sure. But I’ll take all Collins will write.Howard: I’m right there with you, and I’ll definitely be trying out some of his other work now as well. You mentioned earlier that the Quarry novels read with great speed and I have to concur. Collins has the ability to relentlessly pull you forward. I’ve read every one of these and I’m still trying to figure out exactly how he does it… Once you start they’re nearly impossible to put down.In any case, for all of the reasons Chris and I cited above, I’m awarding Quarry a star, just as I’ve awarded my very favorite books/authors/series from the list. If you like this kind of noir, Quarry is a must-read.

Published on November 10, 2014 08:22

Ed Gorman's Blog

- Ed Gorman's profile

- 118 followers

Ed Gorman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.