Andrew Scott's Blog, page 34

October 28, 2013

"Choosing the novella pretty much throws publishing out the window. There is something very freeing..."

- Michael Nye

October 25, 2013

"I started thinking about other kinds of unreliable omniscience, ranging from the trivial (the GPS in..."

- Robert Boswell, in my interview with him

October 24, 2013

"Self-publishing is like fantasy baseball camp. You pay a lot of money to walk out on the field, toss..."

- Andrew Scott

October 23, 2013

"Loss is obviously a big theme for me, and in these stories my characters deal both with loss of the..."

- Ann Packer

October 22, 2013

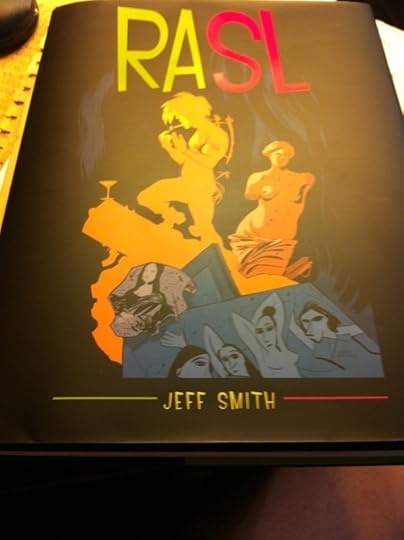

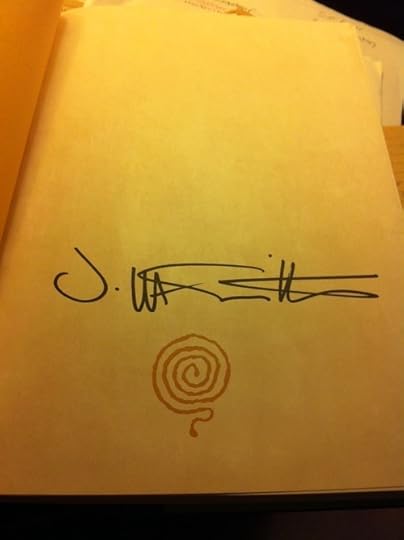

The complete, full-color RASL by Jeff Smith. Signed. At...

The complete, full-color RASL by Jeff Smith. Signed. At Amazon’s price, but purchased from Cartoon Books.

October 15, 2013

The Cost of UP Books

University presses are pricing themselves out of existence. Not all, of course. But most are.

Here’s an example: I’m reading a book, one published this year, that I received through Interlibrary Loan. The cover price is $65.00 (hardcover). It’s black and white, nothing fancy. I recognize that it was printed on demand at a specific factory in Tennessee, which means I also know approximately what it must have cost to produce this book; very little money was spent to bring this book into the world. It features 24 scholarly essays—probably included at little to no cost to the press—and the editor most likely did not receive an advance. The university press has a staff, but it’s unlikely that the UP’s sales are tied to those salaries; university press employees will be paid by the university if a book underperforms.

So why $65? Individuals can’t afford that. Institutions, such as university libraries, presumably can, but why charge them more? Just because they might pay it? That’s still a severely limited audience. My university library, you know from my first paragraph, did not purchase this book for its collection.

And if it’s aimed at a limited audience, why make the book available through places like Amazon, where it’s on sale for (gasp) $57?

The subject matter is the superhero in American comic books. You know, the genre responsible for billions and billions of dollars that flow into Hollywood each year. So the audience really isn’t that limited, either. It might not become a bestseller, but individuals (hundreds, at least, maybe a few thousand) are interested in this topic.

We often have conversations about book pricing at Engine Books. Our current title is a big novel, and we raised the cover price by a dollar, to $15.95, even though it’s twice as big as some of our recent titles.

A buck. And we weren’t sure we should even do that, but researching what big commercial publishers are charging for paperbacks made us reconsider. Bigger publishers also used POD to keep older titles in print. I love Robert Boswell’s Century’s Son, for instance, but its $19.00 cover price tells me that it’s only available because of this on-demand technology, which comes with a higher production cost (but less money—no money, really—upfront). The publisher, Picador, then raises the cover price in order to cover that higher production expense. The book stays in print, and the publisher’s profit margin on that title stays consistent.

And even that practice must be considered humane compared to how most university presses treat cover prices.

October 13, 2013

Alice Munro's books

Sales rankings at Amazon.com as of 11:50 a.m., Sunday, October 13, four days after Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize:

DEAR LIFE #12

HATESHIP, FRIENDSHIP, COURTSHIP, LOVESHIP, MARRIAGE #21

SOMETHING I’VE BEEN MEANING TO TELL YOU #24

RUNAWAY #41

SELECTED STORIES #65

THE LOVE OF A GOOD WOMAN #145

LIVES OF GIRLS AND WOMEN: #259

THE MOONS OF JUPITER #272

CARRIED AWAY: SELECTED STORIES (EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY) #357

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES #447

THE BEGGAR MAID #489

OPEN SECRETS #738

TOO MUCH HAPPINESS #806

FRIEND OF MY YOUTH #963

THE VIEW FROM CASTLE ROCK #1,207

THE PROGRESS OF LOVE #1,633

VINTAGE MUNRO (SAMPLER) #3,454

October 11, 2013

An Interview with _____________________________

I’m cleaning up some old folders and files on my computer this month. Here is an interview I did for a magazine that, for whatever reason (probably editor dipshittery), lost track of the piece and never published it.

How long did it take you to write all the stories in your collection?

The oldest story dates back to 1998. The most recent story was first drafted in 2007. But most of the stories were in recognizable form by 2002, so Naked Summer has taken nine years to make it into book form.

Did you have a collection in mind when you were writing them?

Not at first. But eventually I tried to find a tuning fork, a story that might resonate with the others and point readers toward some kind of unifying theme. That theme changed over time, as did the story I’d considered the tuning fork, which was just one reason the collection took so long to finish.

How did you choose which stories to include and in what order?

I pulled a piece from the collection after it evolved into a novella, what is now the anchor of another collection of stories. I ditched another story after an agent said she didn’t like it. But mostly these are the stories I had to work with — I’m not blessed with dozens and dozens of short stories just waiting to find a home — so I ordered them in a rather simplistic fashion: I began with the shortest, ended with the longest, and tried to separate stories that might have too many elements in common (similar protagonists, points of view, subject matter, length, and so on). Over the years, I’d tried other strategies for ordering the stories, but this grouping just felt right.

What does the word “story” mean to you?

In two words? Trouble and glimpse. Eudora Welty said that “only trouble is interesting” in fiction, and that idea burrowed deep into my psyche. Of course, trouble has many definitions. And this says nothing of the trouble a writer might have in finding publication for an otherwise good book of stories. William Trevor has called short stories “the art of the glimpse,” which I’ve always loved, the way an intense moment, or brief series of moments, with a character can illuminate that character’s life, and thus the human condition, for readers. There is great power in small things. Attempting to write a good story is like harnessing the atom.

Do you have a “reader” in mind when you write stories?

I didn’t have a reader in mind when writing these stories. [Edit to add: Why “reader,” anyway?] But now that the book is out in the world, I’ve met actual readers. This summer I was in Louisville for a week, scoring high school writing exams for a corporation that administers them to great profit. They bring in high school teachers and college professors to score the students’ work, so I found myself at a table with other English teachers not long after the publication of Naked Summer. Many of my co-workers bought the book, and they began talking to me about it during breaks, or before the work days officially began. At first I was uncomfortable with the idea of essentially being held captive by readers who could nit-pick any inconsistency or imperfection in the book. Why does Character X do this or that? But nothing like that happened.

Instead, one teacher asked if any of the stories might appeal to his students — he wanted to teach my work — and another asked if Tim O’Brien was an influence. She thought one particular story had “an O’Brien feel” to it. I thought she was just making nice, or comparing my book to another work of contemporary fiction she knew. But after I looked at my story again, I saw that it uses a paragraph-long list near the end, which is probably something I picked up from many readings of “The Things They Carried,” though it wasn’t a conscious decision on my part. Or, if it was, I’ve long since forgotten about that decision. Later that week, the same reader wanted to talk about Jhumpa Lahiri and Alice Munro, two writers I greatly admire. So I guess now I hope for readers like them, ones who appreciate a good sentence and are open to good stories, and who, at times, might be better attuned to the work than I am as its author.

Is there anything you’d like to ask someone who has read your collection, anything at all?

I’ve found that I don’t have to ask questions — readers are all too happy to share their impressions, thoughts, or objections on their own. I just try to keep my mouth shut and the worrying to a minimum.

How does it feel knowing that people are buying your books?

Many writers would have given up on this manuscript a long time ago, so to see it out in the world, in the hands of strangers, is a good feeling. And, because I was so focused on this collection for so many years, it’s also liberating. I can move on. I began many other manuscripts during the nine years I spent making this book, so I have lots of options now, but this one, at least, can be put to rest. What’s done is done.

What are you working on now?

Two novels. A linked collection of stories. Several graphic novel projects. I like to use all of the burners, the oven, and even the warming drawer.

October 1, 2013

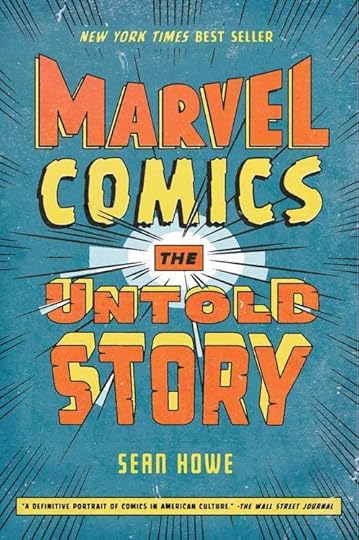

An Interview with Sean Howe

Sean Howe is the author of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, an unauthorized look at the history of the world’s best-known —and arguably most-loved—comic book publishing company.

Written and researched during a five-year period, Howe’s wide-ranging examination takes readers to the company’s beginnings, before it was even known as Marvel—when “Stan Lee” was just the name Stanley Leiber signed to the corny jokes and other pieces he wrote, so they wouldn’t come back to haunt him when he finally wrote the Great American Novel.

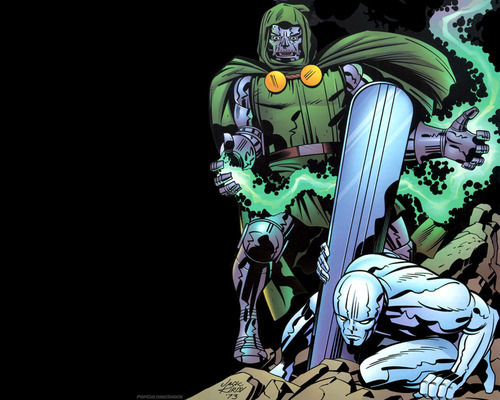

Ample pages are devoted to the years following the publication of Fantastic Four #1, when Lee, Jack Kirby, and other creators rescued the superhero genre and captured cultural lightning along the way, but every key moment up to the release of last year’s top-grossing film, The Avengers, is chronicled with surprising intimacy and emotion.

Along the way, Howe’s uncanny alchemy turns behind-the-scenes glimpses into a page-turner: the story of how a ragtag group of creators and fans helped shape the pop culture landscape of the last fifty years.

Many comics publishers have come and gone. Why has Marvel Comics endured?

Marvel’s been around in one form or another since 1939, which is an impressive lifespan for a company of any sort, but you’re right, in the comic business it’s especially odds-bucking. Martin Goodman, who was a publisher of pulp magazines, waded into the comic-book pool in the immediate aftermath of Superman’s hugely successful debut, thinking it was another get-rich-quick fad. It worked out nicely for him, because Carl Burgos’ Human Torch and Bill Everett’s Sub-Mariner and, most of all, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon’s Captain America were hits right out of the gate.

The comic business lined Goodman’s pockets for about twenty years, and then, in 1954, there was a confluence of bad press: thanks to the public’s panic about juvenile delinquency, there were church-sponsored comic burnings throughout America, and a child psychologist named Frederic Wertham published a book called Seduction of the Innocent that sounded a warning call about sex and violence in the comics, and then there were Senate subcommittee hearings in which you had public officials holding up the most grotesque examples of crime and horror comics. So the point at which Marvel was most likely to fold was in the mid-1950s, when most of the industry fell by the wayside and artists found other lines of work. And for whatever reason, Goodman kept it going. Stan Lee had a desk shoved into an alcove of Goodman’s magazine offices, and he plugged away in near-anonymity, but he had the luck—and taste—to work with a number of brilliant freelance artists.

Two of those artists, of course, were Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, and great ideas just seemed to flow out of them. So in the span of just a couple years in the early 1960s you had the Fantastic Four and the Hulk and Spider-Man and Iron Man and Thor and the X-Men and Doctor Strange, to name a handful. And Stan Lee, through his chummy editorial voice and relentless salesmanship, did a tremendous job of cultivating a feverishly devoted legion of readers. From that point on, it wasn’t just a matter of being a juggernaut in a business sense, but in a narrative sense as well. It was like a long-running soap opera. I think the force of that overarching Marvel Universe saga became, at some point, unstoppable. So that when there were downturns in the fortunes of the entire comic book industry, first in the 1970s and again, even worse, in the mid-1990s, the momentum of the Marvel brand ensured that the characters and their stories would continue in some manner.

One of the book’s epigraphs, written by Stan Lee, parodies the opening of Genesis: “And the Spirit of Marvel moved upon the face of the Writers./And Marvel said, Let there be the Fantastic Four.” The other is a serious comment by Jack Kirby: “Ideas can never be traced to any one source. They are tossed back and forth between people until the decision makers step in and choose what they think is a success formula.” Which of these creators is more important to the history and future of Marvel Comics?

I find it very hard to imagine that Marvel Comics would still exist today without both of these men. If you made a comparison to filmmaking, you could probably say that Jack Kirby was the director of the films they made together. He was a visionary. His ideas worked on a grand, ferocious scale. He may well have done the heavy lifting of the plotting, and as the artist, he laid out the way the story was told, and controlled all the visual elements.

On the other hand, Stan Lee was not just an incredible editor—he was Marvel’s default art director, he was the talent scout, he wrote sparkling dialogue, and he was a world-beating spokesman. And he was tenacious. He worked at Marvel from the age of nineteen to the age of seventy-five, and tirelessly promoted not just the company but the medium as well.

“On the eve of The Avengers [movie] release,” you write near the end of the book, Stan Lee “was asked if he felt the comic book industry had been fair to its creators. ‘I don’t know,’ he replied. ‘I haven’t had reason to think about it that much.’” Do you believe him? And did Jack Kirby get screwed by Marvel Comics?

I’m sure he’s thought about it at various times, and perhaps I should point out in that same interview he noted that artists were savvier than they used to be because “they know what happened to Siegel and Shuster” [creators of Superman]. In fact, at one time Stan Lee was quite vocal about the treatment of creators. At least as early as 1969, he complained privately about the comics industry—complained that he didn’t own any of his creations, and, disappointed that Martin Goodman hadn’t given him a cut of the profits from Marvel’s sale, admitted that he felt no loyalty toward the company. And a few years later, he gave a speech at the National Cartoonist Society in which he said the advice he’d give to a creator with an idea would be to “think twice before you give it to a publisher.” It’s also worth noting that Lee wanted Kirby to leave the comics industry with him, back in 1969.

But to cut to the chase: Jack Kirby, or now his estate, deserves a much bigger cut of the profits that Marvel is swimming in. That seems, to me, undeniable.

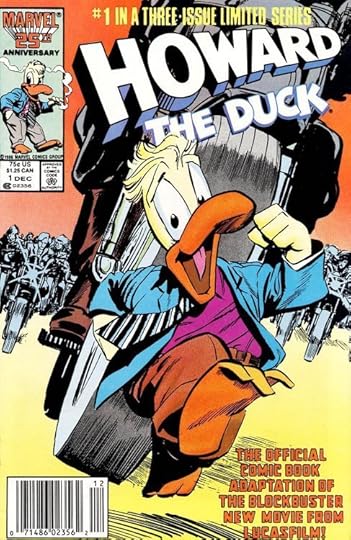

Your rendering of the company’s story pays special attention to a cast of rebels perhaps unsuited to other lines of work. Stan Lee once posed naked to promote the company. Steve Gerber, creator of Howard the Duck, is another example, but even editors and decision-makers had a defiant streak. Why is this element so prevalent in the comics industry, and does it play a role at Marvel today, now that Disney owns the company?

Well, Stan Lee posed for the centerfold of a goofy lark of a comic that came out in 1984, but yeah, I think it’s in their blood. A lot of these guys were, to borrow the tagline from Gerber’s Howard the Duck, “Trapped in a world they never made.”

I’m not sure that comic creators are any more rebellious than the people who populate other artistic pursuits. I think that if it seems like they’re ill-suited to the constraints of business, well, that might have something to do with the power dynamic within the industry. By that I mean, in the music business, or in the film business, idiosyncratic and independent behavior is indulged as an artist’s prerogative. In the comic business, for a long time, that kind of behavior wouldn’t be tolerated. These days, because independent publishers have offered another route for the most restless of the creators, it’s less of a problem.

But that’s another reason I wanted to write this book. Despite their individuality, a lot of writers and artists were just subsumed into the torrent of Marvel. Their identities were eclipsed by the identity of Marvel Comics. I think it’s important that we give them their due.

You also edited Give Our Regards to the Atomsmashers!: Writers on Comics, featuring essays by the likes of Geoff Dyer, Aimee Bender, Chris Offutt, Myla Goldberg, and other prominent literary writers. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story showcases blurbs by Jonathan Lethem, Patton Oswalt, Sloane Crosley, and Chuck Klosterman. There was a time when reading comics wasn’t cool; now it’s uncool for someone to say they don’t like comics. What prompted this cultural shift? What can reading about the history of one comic book publisher teach us?

I can vividly recall the cultural moment. There was a kind of critical mass that had never really happened back in 1986, the year of Maus and Watchmen and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Maybe the breakthrough that was needed was Hollywood’s stamp of approval, rather than simply “Comics Aren’t Just For Kids” headlines and critical kudos. In 2001, Michael Chabon’s novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay won the Pulitzer, and Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan won that Guardian award, but also Terry Zwigoff’s film of Ghost World hit theaters, and in 2002 the Spider-Man movie came out. Shortly after that, I remember a friend of mine “admitting” to me that she didn’t really read comics, and there was this shame in the way she said it that…well, let’s just say that I wish girls had been so impressed by comic books when I was twelve years old.

Do you remember when you’d walk into a Waldenbooks, and everything related to comics was stuffed in the Humor section? Not just Heathcliff, Marvin, and Cathy, but Sniglets and Gross Jokes? You’d be pretty lucky to find Jack Kirby’s Marvel stuff, to say nothing of Love & Rockets. My understanding is that Chris Oliveros and Art Spiegelman lobbied a book industry group to identify a “graphic novel” category. In retrospect, that may have been the tipping point.

As to what a history of Marvel Comics can teach, first of all, I hope that it would give people a greater interest in and respect for the actual medium. I think there’s a tendency to reduce Marvel to its intellectual property, its characters, when in fact even superhero comic books are not just about the superheroes. There’s a very legitimate art form at play, and just because someone has seen the movies and the t-shirts doesn’t mean they’ve gotten a very good glimpse into what makes the art form important.

I also think that the story of Marvel has a lot to tell us about the way we create, sell, and consume art. “Pop culture” is such a fascinating mix of contradictions, and creative urges and commercial forces are very seldom a happy marriage. This is, of course, true for any mass entertainment, from arthouse films to hip-hop, but in the case of Marvel Comics, the tensions are exacerbated by the weird industry traditions of corporate ownership. And on top of that, there’s the cadavre exquis nature of the collaborations; people build on top of each other’s works and then pass them along to the next in line, and it all ends up belonging to the company in the end.

Like any good historian, you keep yourself out of the story you tell in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. What is your untold “origin story” as a reader of comic books? Why are you so interested in the stories behind the stories?

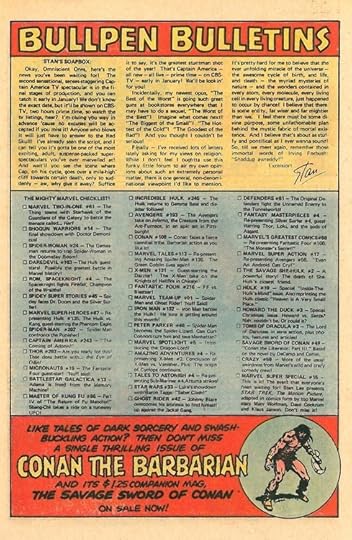

I’m a lifelong comics fan, and so I grew up reading the “Bullpen Bulletins,” which was the monthly column that appeared in every Marvel Comic and which was one of Stan Lee’s masterstrokes. It’s hard to get across just how powerful this was in terms of branding to a legion of kids, but it basically made you feel like you were part of a big family, and like the Marvel offices were a sacred and wonderful place wholly defined by creativity and zaniness. Much of the time, Marvel was a creative and zany place, but of course that wasn’t the whole story, and so when we readers grew up, it was like finding out that there were all these things you didn’t know about your favorite uncle.

Readers won’t be surprised that ample attention is given to John Byrne, Chris Claremont, Frank Miller, and other prominent creators in the post-Lee/Kirby years. But of the many individuals who passed through the Marvel Bullpen through the decades, whose story captivates you the most?

Let’s see, there’s Jim Steranko, a coalminer’s son who was performing as an escape artist by the age of sixteen, and racking up a string of auto-theft charges by the age of eighteen, before turning to card tricks, fire eating, rock guitar, and drawing comic books.

Then there’s Jim Shooter, also from an impoverished Pennsylvania family, who started writing for DC Comics when he was thirteen or fourteen, to help put food on the table, and who burned out by eighteen; fans of his tracked him down a few years later working at a Kentucky Fried Chicken and eventually he went on to be Marvel’s editor-in-chief for most of the 1980s. He did a lot to change the industry, and he also became one of its most polarizing figures.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the guys behind the scenes are every bit as captivating and complicated as the characters on the page.

Wider audiences already know Spider-Man, the X-Men, and Iron Man, and even minor characters, such as the Black Widow. It appears even Ant-Man will become a major motion picture. Who are your favorite Marvel characters not known by most audiences?

How about Angar the Screamer, the disillusioned hippie who blasts enemies with bad vibes? Or Nekra, the bikini-clad albino, born to an African-American cleaning lady, whose superpower comes from the raging hatred inside her. These are not going to make it to the Cineplex, but they’re a lot of fun to unpack.

As far as Marvel characters that do have a shot of going Hollywood, Matt Fraction and Ed Brubaker’s Iron Fist seems practically camera-ready to me.

You’re a lifelong comics fan . Do you plan to write “The Untold Story” of DC Comics or other publishers?

I have been absolutely immersed in this for the past three years, which is why I think I’ll leave the DC Comics volume to someone else. I’ll always be an enthusiastic student of comic history, but for a while it will be nice to flip through an issue of, say, ROM: Spaceknight without thinking too hard about how someone’s freelance contract status played into the subtext of page sixteen.

Author’s Note: Last year, a major online venue asked me to interview Mr. Howe before Marvel Comics: The Untold Story was released in hardcover, but then assigned the interview to another writer, as well. Did I try to then guilt-trip the editor into accepting another piece? You betcha.

I’m happy to promote the paperback release of this book.

September 18, 2013

"It’s difficult to live on writing, especially the kind I produce. I set off without the least idea..."

It’s difficult to live on writing, especially the kind I produce. I set off without the least idea of what the difficulties would be. The only time I felt that I had made a terrible mistake was near the beginning, when I was living in Madrid. I had taken an agent in New York, someone who had written me when my first story appeared in The New Yorker. I looked up his name in a book called something like The Artists and Writers Yearbook in the USIS library in Salzburg. I thought it would be a good thing to have an agent in America because I was moving around all the time; it didn’t occur to me that someone with his name listed in such a book might not be respectable—it still puzzles me. I sent him stories, which he said he was unable to place. The truth was that he did place the stories but kept the money. To keep The New Yorker from finding out he wasn’t paying me, he had told the magazine my address was Poste Restante, Capri. The letters The New Yorker sent were returned, of course, but no one there knew much about me and they might easily have thought I was some sort of lunatic who did not pick up her mail. The result was that by the spring of 1952, in Madrid, I was destitute. I don’t mean hard up; I mean lacking in everything from food to paper to write on. But the worst of it was my belief that no one wanted to publish my work—I believed the agent when he said he appreciated the stories, but no one else did.

Then one day in Madrid I came across a copy of The New Yorker (I don’t remember where or how, for I could not have afforded to buy it) that to my intense astonishment contained a story of mine. I had met William Maxwell, my editor, in 1950 before I left for Europe, but we were still “Mrs. Gallant” and “Mr. Maxwell”—or would have been if I had received any of the mail he was trying to send me. He was my first fiction editor, a relationship that lasted for twenty-five years. Having him was an incredible stroke of luck. So I wrote, just saying that I wished I had been shown the galleys. I remember that his answer began “thank God we now know where you are” and that my agent had said I was in Capri. I hadn’t mentioned money—I seemed more upset that a story had been published without my being told—but he went on in the letter, More important, did you get the money for the two stories? Two stories? There were stories in other magazines as well. I shall spare you the rest of it, except to say that one day I read, I think in the Herald Tribune, that the agent had been killed in a motor crash.

The greatest damage, as far as I was concerned, was my loss of confidence. The feeling of hopelessness and dismay I experienced when I believed every story I sent him was a dead failure never really left me. Actually, almost every writer I’ve known has something of that. It is not uppermost in one’s mind. If it were, no one could ever write anything.

”- Mavis Gallant, The Art of Fiction No. 160

Andrew Scott's Blog

- Andrew Scott's profile

- 9 followers