Andrew Scott's Blog, page 28

April 25, 2016

Frank Miller, Sin City: That Yellow BastardI always love when...

Frank Miller, Sin City: That Yellow Bastard

I always love when the lettering goes funky to better match the mood or atmosphere of a story, such as in these skewed captions.

March 20, 2016

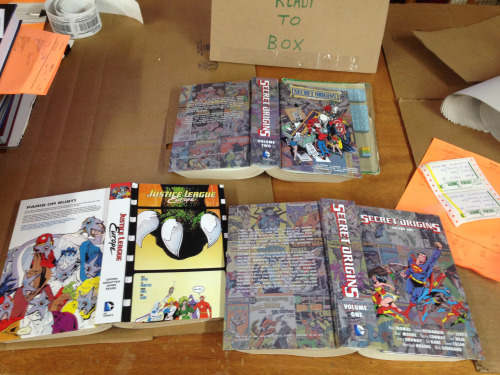

Custom binding comics is my newest interest. Here are my first...

Custom binding comics is my newest interest. Here are my first binds.

June 28, 2015

My Academic Job Search Postmortem, Part Two

In Part One, I shared nine observations made during my recent job search.

Before I begin Part Two, in which I’ll compare myself to five writers hired this year instead of me, I want to say that I’m (fairly) happy in my current position as a full-time, non-tenure track professor with a 4/4 teaching load. I have an admin position, so the load is reduced to 3/3. I teach partially online every semester, either hybrid sections (50% online) or fully online courses. My department is very considerate of my scheduling needs, which is just great. And, while I (like everyone) would like to be paid more, the department chair took to the dean a proposal I helped develop that argued for higher salaries, and it worked (sort of)—we got a 3% raise. Not great, but certainly not nothing.

So why the job search?

In short, I’d like the writing time afforded to TT creative writing faculty. A TT faculty member’s writing is institutionally rewarded or supported. Obviously, some institutions do a better job of that than others. My 3/3 plus admin load (still a 4/4, basically) is a lot of work. Teaching two courses a semester for a lot more money sounds good. Or, to put it another way, I want to make my writing a priority in my life, which is hard to do with a 4/4.

The job market is brutal. I’m confident I could land a TT job in the next year or two, but I also don’t want to move. I like our house. I like the affordable city in which I live. Yadda yadda. And, truthfully, there are only a few things I can do to rise above the pack now. One is to get a Ph.D., which I don’t really want to do. Another is to publish another book (let’s be honest, a novel), ideally with a big press. I could also try to win a big award, but since I haven’t applied for any recently, that’s not likely.

The five positions below aren’t necessarily the ones I most wanted. For many of the jobs, I don’t know who was hired. In other cases, I don’t know the writer who landed the job. But these five positions in particular help paint a more accurate portrait of me as a candidate for such positions. Departments can afford to be hyper-selective—if not about overall credentials, then about their own particular needs, however idiosyncratic they might appear to outsiders.

Without further delay…

Hire #1—West Coast

This position was “open genre,” which means all manner of applicants might have applied. There are more poets out there than you can imagine, and they are all conditioned to live off of the academic ecosystem. By contrast, at least some fiction and nonfiction writers can—or think they can—make a living from their writing. In the end, this department hired someone with two books in genres that aren’t mine (one poetry, one nonfiction). This hire also has a Ph.D. in creative writing and appears to be three years younger than me, FWIW. Sports teams have to decide if they should draft for specific needs (cornerback, third baseman, etc.), or grab the best player currently available. Did this department want a poet/memoirist? If so, they likely got a good one. I’ve never heard of her before, but her credentials are solid. The Ph.D. could be a huge factor here, too, especially since the committee was comprised of something like 15 people, I later learned, and only a couple of those were creative writers. One writer on the committee let me know that I was out of the running early on, which I appreciated. I reviewed his book a few years ago, and a quote from my review can be found on his faculty website. I don’t think the committee really knew what they wanted when they placed the ad. Therefore, there’s almost nothing I could have done to better present myself. A simple culling of the herd—by deciding, after applications are in, to only consider writers with a Ph.D., or writers with two or more books—could have kept me on the outside looking in.

Hire #2—East Coast

I wanted this job for a number of reasons—it’s a short train ride from Manhattan, and is lodged in a community I’ve been to before and like, one where a few of our friends live. The department member who shared the job ad on Facebook is a talented writer and a nice guy, as far as I can tell. But I had to say no to his story collection a few years ago when he submitted it to Engine Books. Here’s the thing: I have to say no to almost every submission, and some of those writers are going to be in a position to affect my teaching career. Will all of them hold a grudge? No. But a few might, which is fine. This guy likely didn’t do that. The writer hired is young, but has excellent story publications and editorial experience. The writer hired, however, does not have a book. Is one under contract? Maybe. I can’t know that. But this hire suggests that some departments (not many, but some) still think about potential, not production. That should be encouraging, but it’s not.

Hire #3—West Coast

I knew there would be tons of applicants for this gig in a popular literary city. In the end, the department hired a writer with more books than me who already lives there. Whaddya gonna do? I had no shot at this one.

Hire #4—West Coast

Department hired a writer with one book. That one book—flimsy as it is—has done quite well for the author. I wish my own flimsy book had garnered such attention. This writer’s reputation has exceeded his actual abilities. The buzz around his first book reminds me of the hype surrounding Junot Diaz before Oscar Wao was finally published. That is, this writer’s second book will have huge expectations, and if he can deliver—as Diaz delivered—his career will go supernova. Can he teach? He appears to have little to no experience. But some programs care more about reputation that anything else. I’m sure he’s good at a cocktail fundraising event.

Hire #5—Planet Texas

One of the long-tenured professors in this department often talks to me about teaching, and she gave me some excellent feedback on my CV a few years ago. Not long before I applied, this professor asked me if I could share PDF files of the stories I teach because she wanted to change things up on her syllabus. But guess what? She wasn’t on the hiring committee, and I don’t ever ask someone for that kind of favor. The department hired a writer with two books (one collection, one novel). I remember her from when she was an editor at a literary journal. I don’t feel bad about this missed opportunity. It’s still in Texas, for one, and I wasn’t sure about living in Texas. The department hired a talented writer who is probably good in the classroom. She might be a mini-version of the tenured professor I mention above, which is a good thing for the program’s future.

There’s a lot more I could say, of course. In Part I, I mentioned some of the other reasons why I might not always land an interview. Over and over again, though, I see a pattern: Writers who put their writing first are rewarded in academia. Not writers who put their teaching first. Not writers who put their university or community service first. And, whatever else I may have accomplished over the last 15 years, I can’t honestly say I always put my writing first.

But that’s going to change.

June 1, 2015

Some Thoughts on My Book’s Anniversary

My first book came out four years ago today. Here are some thoughts:

1. Having a book has not transformed my life. No agents have approached me. I have been unable to secure a tenure-track teaching position, despite having a book—something that, six or eight years ago, I considered the one roadblock on that path. I’ve had a few interviews, but the truth is that 150 applicants for each position have one book; another 75-100 have two books; probably 30-50 have three or more books. For assistant professor/entry-level positions! Having a book, it turns out, is nothing special. No big whoop.

2. I haven’t written much prose fiction since my book came out. Peers who published a book around the time of my book have published a second book now, or a third, or maybe they have two titles contracted. This makes me feel like a slacker—like a big fucking loser, actually. I’m also not a write-every-day-but-publish-once-a-decade writer, either. I’m not Junot D. or Donna T., let me tell you.

3. #1 and #2 are related. I didn’t feel like writing much prose fiction in 2011. Or for the next year or two, really. What’s the point? But also, by the time my book came out, I’d kind of forgotten how to write. I spent so much time revising Naked Summer that I essentially became an editor, not a composer.

4. In 2012, Victoria Barrett let me join Engine Books to work as an editor, which has taken a lot of my time and creative energy, but I’m very proud of the books I’ve helped guide into the world. There’s no denying, however, that I’ve worked to shape other people’s stories and words, not my own.

5. When I have written prose, it’s mostly been nonfiction. I didn’t see that coming.

6. I did co-write a graphic novel script, and I have developed (or am developing) some other comics-related projects. This was my first writing-related interest, anyway. Comics are the reason I’m a writer. I feel like the river’s returned to its original source or something. Right now, writing comics—or trying to—is a lot more fun than writing prose. That doesn’t mean I’m not still poking at a few stories or novels-in-progress. (Yes, plural. I have novels in progress.)

7. The ideas have never stopped coming. I would need two or three adult lives to get to them all. So I’ll have to choose the projects I most want to write, not the ones I think will interest an editor or hiring committee or—this is the hardest one—make my wife happiest.

8. For two or three years, I said I would never again write an unlinked story collection. But you know what? Maybe I will. Some of the best agents and editors in the country said they liked my writing, but they wanted me to have a novel instead—and I let that worm inside my head. Eventually I found a publisher that was interested in my story collection, one that had published about four or five other writers I admired. But honestly, I wish I hadn’t published my book when I did. Not because it’s not good enough. I’m not embarrassed by it. In fact, I think it’s better than a lot of debut story collections from Big 5 publishers that have appeared since then. But you only get one chance to make a big impression. That it’s a story collection might help—maybe some future agent can sell one of my novels, and the publishing house won’t even care that I published a story collection, one that will likely be out of print by then, anyway. In that sense, maybe I will get a second chance to make a first impression.

9. I worked my ass off to promote my book. The publisher wanted to try an Amazon assault—to get as many people as possible to buy my book on June 1, 2011, its official publication day (never mind that it was actually available for two weeks before that). In short, I worked it like Mary J. Blige. A lot of people bought my book on June 1, which drove Naked Summer up the Amazon sales charts. I think it cracked Amazon’s Top 500, and was #2 on the Short Stories list—one notch above Ann Packer’s book, a writer I admire and now know a little, and two notches above a book by Stephen King. Stephen King! Pretty cool, right? An author my parents could name. But my publisher only designated 15 copies for review, and only if a would-be reviewer inquired. There were no ARCs produced. There was no follow-up plan. Basically, I got everyone I know—which is a lot of people, it turns out—to buy a copy of Naked Summer, and then…that was pretty much it. Within the week, my book began to fall off those Amazon sales charts.

10. I was seriously depressed the year my book came out. I was an asshole to everyone, including my wonderful wife—or especially her, since she was here. I discovered streaming Netflix and watched whole seasons of shows I’d never before cared about by propping the iPad on my chest and laying in bed for hours every day. Finally my wife told me to knock it the fuck off. She’s good like that. I started therapy, which sort of helped, though my therapist was kind of a flake. I started taking bupropion, which helped a lot—and still does.

11. Around the time my book was published, Engine Books was really taking off, so I got to see how Victoria worked with her authors. I was so jealous, to be honest. I realized that’s what I wanted—to have an editor who believed in me work hard on my book, to challenge me, to make the book better on every level. A lot of writers don’t like to talk about their own behind-the-scenes experiences with publishing, at least not in public. (But over drinks? Hell yes, they do.) But my publisher asked me to change two things: 1) He wanted the book to be called Naked Summer, which is what I had called the manuscript for several years before making an impulsive change right before submitting it to him (easy change); and 2) he wanted me to revise the last line of the last story—the title story—because he thought it was a downer. Because that was the only thing we ever discussed regarding my manuscript, I made the change. We didn’t edit the manuscript together. I didn’t accept or reject changes. That was not part of the process. No one at the press proofread the manuscript. Thankfully, I’m married to one of the best editors around, and she gave my manuscript a good ass-kicking after it was accepted, but before it was published.

12. I typeset my own book. The publisher was busy with a poetry festival and it didn’t look like we’d make our deadline. Because I knew how to typeset, I offered. For this service, I was paid with another 30 author copies. Of course, I wanted to make revisions during the typesetting process, which I do not recommend.

13. There’s a lot more I can say about this process, but you’ll have to buy me a drink or two. However, I do want to say that while I was not in a hurry to publish, I still think I published too soon. I’m now almost 39 years old. We have a son now, and a small press to run. My dad died. I still teach more classes each year than my contract stipulates. I don’t know that I’ll suddenly be able to start writing more than I have over the last four years, but I feel, in some ways, like I have more reasons to write than ever before.

Fiction? Nonfiction? Comics? Other stuff?

Yes. Yes. Yes.

April 28, 2015

My Academic Job Search Postmortem, Part One

A review at the

end of an effort or project can be known by many names, depending on the field

or specialty. Sometimes it’s a debriefing

or a completion report, and the goal

is almost always to articulate the lessons

learned during the process.

I’m using postmortem here, however, because

my academic job search is dead. D-E-A-D. As a doornail, dodo, et cetera.

Not because I’m

no longer a viable candidate, mind you, but because—with only a handful of

local exceptions—I will no longer bother to look.

Here are nine observations

made while examining this still-warm corpse:

1) Married? Kids? Care

about where you live? Good luck

Younger writers

are more likely to be unmarried and to not have children, which means they’re

better candidates for uprooting and moving to far-off (and perhaps less

desirable) stops on their Nomadic Academic Adventure™.

I’m 38, which puts

me in the second-largest age range for jobseekers in creative writing, at least

according to self-reported data on the popular academic jobs wiki. Writers

younger than me comprise the largest group. My wife and I own a home, and we

just had our first child. I’m not going to ask my family to uproot unless the

right job comes along. This puts me squarely at odds with the pervasive

mentality in academia that we should go

where the job is. This mentality, IMO, is one reason so many academics are

unhappy.

2) The MFA is on its way

out

The MFA is “the appropriate terminal degree,” according to the Association of Writers and Writing Programs

(AWP). Increasingly, however, job openings require a PhD, or

else the ads say “PhD preferred,” which is the same thing. Many departments this

year sought to hire someone who could teach creative writing and literature and business writing and

you-name-it. I strongly believe these “open/mixed” listings will dominate

future job seasons. Many committees bring in PhDs because it’s just easier to

push those candidates up the chain of command. If the trend of hiring

generalists continues, then those with only an MFA will find themselves on the outside looking in.

This year, my

department hired a tenure-track poet. In the group of three finalists, two had PhDs

and the other had a law degree. All three had also earned an MFA along the way,

which means my degree is increasingly seen as just another stop on the academic

road creative writers must pursue. Pay special attention to departments that

hire two positions in a given year. Often, an MFA hired will have a book or two,

while a PhD hired will have published a few articles.

The MFA might

still be a terminal degree, but not in the way we used to mean. Writers in

academia who championed the MFA have lost, plain and simple. That means you, AWP. You lost.

3) You have a published

book—nobody cares

Publishing a

book is no longer a distinguishing characteristic, especially for writers in

academia who only have an MFA—every serious applicant has a book. Many have two

books, or one book with two more under contract. Hiring committees can decide

to make the first cut based on such a detail; if the group decides to only consider

applicants with at least two books, the pool shrinks dramatically. Dealing with

100 applications is still a lot of work, but it’s much easier than looking at 250.

Applicants must come to terms with this: Your qualifications may exceed every listed

requirement and the committee can still choose to dismiss your materials with

nary a glance.

Most committee

members don’t know anything about small press publishers, either, and that’s

where the majority of books of poems and short stories are published now. This

year, I asked a few seasoned writing professors to look at my CV, and the only

potential concern raised—and they all stressed that it was only a potential concern—was that hiring committees

might not know anything about Press 53, the publisher for both my story

collection and a fiction anthology I edited.

Maybe they are

right. The kicker, of course, is that tenured writing faculty at several of the

universities to which I applied have used their Press 53 (or other comparable

small press) book to secure tenure. But they were already on the inside.

4) Teaching experience

doesn’t matter

Every job ad and

department claims to care about teaching, but it really doesn’t matter that much.

A writer who’s taught as a graduate assistant—and maybe for an additional year

or two after finishing the degree—is a more appealing candidate than someone

like me. I have taught university writing courses since 1999, and I’ve held the

same full-time position off the tenure track since 2002. Instead of suggesting

that I am not a job-hopper, that I’m someone who stays in one place for a

respectable amount of time, this detail actually conveys that I’m obviously a loser.

My official title, Assistant Professor, also doesn’t help during the job

search. Once during a

campus visit, a dean asked why I hadn’t become an associate or full professor

after more than a decade in my current position. She gave me the husky stink-eye

when I explained, as if I were trying to get away with something. For the

record, most positions like mine carry a similar title.

Here’s another True

Life Scenario™: I applied for a tenure-track job a few years ago, even though I

knew the visiting professor—a writer I had come to know—was clearly the inside

candidate. Sure enough, they hired him. He admittedly didn’t have much teaching

experience, and he didn’t really like the city. Later, he confessed that he was

worried about me and other writers with tons of teaching experience. The

university talked a good game about its commitment to teaching, but I knew that

was just lip service. His writing had already won a few prestigious awards, which

was more than enough to win them over, even if they had reservations about his

in-classroom abilities. The right book or award always trumps teaching experience.

5)

Sometimes the numbers are not in your favor

I have taught upwards

of 3,000 students in more than 200 sections of university writing

courses—freshman composition, introductory creative writing, fiction writing,

screenwriting, and so on, and I have delivered that instruction in nearly every

possible learning environment (f2f, online, hybrid, and so on). I have accepted

overloads, assumed teaching duties in other classes mid-semester when the

instructors were no longer able, and designed or redesigned courses no

one else wanted to teach. My work has been deemed meritorious for eleven of the last twelve years, and the group of peers who didn’t award me merit that one year might have been on the pipe.

In most fields,

this would mean I’m a proven veteran who can be trusted to do the job right.

But if, like me,

you’re a member of the Writing Professor Corps, Armored Tank Division®, then you’re

just another grunt sent into battle before anyone else, not an officer

deserving decoration.

You thought you

were building up a CV and gaining a wide variety of experience? Nice try,

dingleberry. Limiting your chances of ever finding a better job is more like

it.

6) The competition is

fierce

A few years ago,

I was a finalist for an MFA director job that received almost 300 applications.

A major research university in the same city received close to 800 applications

that year. Just the other day, I finally received a ding letter for an open

genre/open rank position that I’d applied to six months ago: “We received over 300 applications for our position, the

majority of them from candidates with tenure at premier Universities and

Colleges both in the United States and abroad. The pool, in short, was

dazzling.” At least six other positions I applied for this year had a applicant

pool of 300 or more. I’m sure there were many others, too, with similar

numbers.

It’s understandable

that a job near New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, or Portland—or

any place where creative people might like to reside—would draw a high number

of applicants. But even jobs in small-town Georgia and South Dakota receive

more applications than hiring committees should have to endure. And thousands

more writers graduate with a terminal degree every year, so this won’t ever become

easier.

Let’s say that

30,000 people have earned an MFA since I earned mine. If only 10% of that crop continues

to write and teach—and assuming there is equal distribution among the most

common genres (poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction)—then I could potentially compete with 1,000 other

fiction writers for every decent job advertised.

I’m no

statistician. If I had such abilities, I’d work on Wall Street or for a Major

League Baseball club. But the odds don’t seem to be in your favor, Katniss.

7) Where you studied

matters more than what, or with whom, you studied

The writing program

I attended was as good as any of the other five programs that offered me an

assistantship—better, I would argue. My professors, who were the only reason I

attended the program, retired or moved on to more lucrative gigs. In

retrospect, attending a more recognizable program—Iowa, say, or Columbia—would

have better served me on the job market. But I don’t think it would have done more

for my writing.

Alternately, I

should have considered pursuing a PhD after the MFA, but even then—after

teaching for three years and earning a graduate degree—I was still grossly

uninformed about academic job-related maneuvering. My program was an MA when

I started, and I didn’t know the difference one letter made. It became an MFA

before I graduated, and I had the choice between walking away with the MA or

continuing for one more year to earn the terminal degree. By then, I knew the MFA

might allow me to teach. A few months after graduating, I was hired full-time at a university in my home state, but I didn’t know right away what a

non-tenure-track job entailed, or why it could be problematic. I just knew I’d landed a teaching job right out of grad school, something few of the program’s graduates had ever done.

8) What’s in a name?

So you’re a

poet? Call yourself a cinematic poet who writes Scriptverse™, as you’ll

have a better chance of standing out. You can be hired for any poetry, screenwriting, or open genre position. Bonus: Throw around the term “digital humanities” in your materials,

as absolutely no one knows what that actually means. The committee will

probably grant you a first interview.

Also, your specialty doesn’t really matter for creative writing positions. You’re really a poet, but your many prose poems could be flash fiction in the right light. You’ll be hired for the fiction gig. Fiction, creative nonfiction—it’s all just prose, isn’t it? (American literature, medieval literature—it’s all just books, isn’t it?)

9) The academic jobs wiki

is your frenemy

Even though I’ve

made reference to the wiki in this post, I advise using it only to learn of new

job opportunities—then leave the site to find the details of those

opportunities. While the wiki can illuminate certain aspects of the academic

job market, the anonymous interactions are mostly a cesspool of either desperation or arrogance, if not both.

iN PART TWO, I’LL GET INCREDIBLY PERSONAL AND COMPARE MYSELF (FAVORABLY OR UNFAVORABLY) TO AT LEAST FIVE PEOPLE HIRED INSTEAD OF ME.

2015 Reading List Challenge (Adapted for my own needs and interests)

1.

A

book that became a movie

Raymond

Chandler, The Big Sleep

2.

A

book with a one-word title

Jeff

VanderMeer, Annihilation

3.

A

book of short stories

Laura

van den Berg, The Isle of Youth

4.

A

book from a small press

Jared

Yates Sexton, The Hook and the Haymaker

5.

A

book based on a true story

Truman

Capote, In Cold Blood

6.

A

book more than 100 years old

Emily

Brönte, Wuthering Heights

7.

A

book based entirely on its cover

Duane Swierczynski, Canary

8.

A

book you’ve pretended to read

Homer, The Odyssey

9.

A

book you can finish in a day

Justin

Torres, We the Animals

10.

A

book in translation

César

Aira, Shantytown

11.

A

graphic novel

Scott

McCloud, The Sculptor

12.

A

book you own but have never read

Emily St. John Mandel, Station

Eleven

13.

A

play

David

Mamet, Speed-the-Plow

14.

A

banned book

Vladimir

Nabokov, Lolita

15.

A

book you previously started but never finished

Dashiell

Hammett, Maltese Falcon

16.

A

Pulitzer Prize-winning book

Jennifer

Egan, A Visit from the Goon Squad

17.

A

book by a Nobel Prize-winner

Alice

Munro, Family Furnishings

18.

A

book by an author you’ve never heard of

Leonard

Gardner, Fat City

19.

A

book written by an author under 30

Anthony

Marra, A Constellation of Vital Phenomena

20.

A

book written by an author over 70

Elizabeth

Spencer, Starting Over

21.

A

book of poetry

Sharon

Olds, Stag’s Leap

22.

A

young adult book

Laurie

Halse Anderson, The Impossible Knife of

Memory

23.

A

bestseller

Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist

24.

A

book with a color in the title

Walter

Mosley, White Butterfly

25.

A

book that came out the year you were born

Renata

Adler, Speedboat

April 18, 2015

Two recent blog posts...

Over at the Engine Books blog, I am beginning to write a regular column on publishing and the business of writing.

You can read my first two posts:

Who Teaches the Business of Writing?

Writers who teach are generally unprepared to teach the business of creative writing…

AND

I’m the One Who Wants to Be with You

Write your best. Approach publishers with professionalism. If you want to work with a publisher, make sure you like (at least some of) their books. How would you act if you were having a meal with that editor? I think you’d be polite. But something about sending out work or approaching publishers/presses at a book fair makes some writers lose their common decency.

March 25, 2015

Last summer, Rachel Riederer interviewed me for “The Teaching Class,” an essay she published in...

Last summer, Rachel Riederer interviewed me for “The Teaching Class,” an essay she published in Guernica , about adjuncts and non-tenure track faculty. She could only use so much of what I said, of course, but now that her piece has been referenced in this New Yorker article, too—with my story anonymously summarized there—I felt I should include her original questions and my full answers on this blog for anyone who might be interested.

In terms of background, I’d like to know when you started teaching, what subject, what university? And then how long had you been teaching when you had the dust-up?

I started teaching as a graduate assistant at New Mexico State University in 1999. English departments call graduate students who teach “graduate assistants” or “teaching assistants,” but in truth, they’re not assistants at all. They’re almost always solely responsible for choosing class materials, planning lectures and in-class lessons, grading, and so on, and that was my experience, too. I received four days of training before I was turned loose in the classroom for the first time. On the fifth day, the department chair said, “Any questions?”

I was 22 years old. Some of my students in that first semester were older than me. And once I got over the shock that someone was dumb enough to let a 22-year-old teach a college class, I realized I was quite adept at it. You have to know the subject. You have to know how to relate to other people who may not care about the subject. And you need common sense. If you have those three, you can begin to learn how to teach, but after a certain point, it never gets easier. You’re never on cruise control.

After I finished my M.F.A. at NMSU in 2002, I was hired by Ball State University in my home state of Indiana—a full-time, salaried contract position with benefits that I have to this day. Between 2002 and now, I’ve also taught at a few universities as an adjunct. Most notably for your purposes, I taught three classes per semester at Marian University in Indianapolis (2008-2011).

When the situation I originally told you about occurred in February of 2011, I was finishing my third year as an adjunct at Marian, but it was my twelfth year as a writing instructor at the college level. At Marian, I taught the required first-year writing courses, one of which was also a literature class. At Ball State and other universities, I’ve taught fiction writing, screenwriting, and other creative writing courses, too, though first-year composition is the reason I have had these jobs.

What were your working conditions at the time? (How many courses; amount you were paid, if you feel comfortable saying; what kinds of administrative support / office space / etc, did you have access to, or not have access to?)

I taught three courses per semester as an adjunct at Marian. Had I been assigned more classes per semester, I would have been considered a full-time employee and given an actual salary. Instead, I was paid $700/credit hour, or $2,100 per three-credit course. By contrast, my full-time course load at Ball State meant four classes per semester, and even my starting salary in 2002 meant that I was paid more than $3,500 per course. Now, after twelve years, I make a bit more than $5,000 per course, though my base salary after more than a decade of meritorious service is only finally equal to what many of Ball State’s named peer institutions pay as a starting salary for someone in my position.

There were a handful of us adjuncts who taught English or communication classes at Marian. We were housed in one office with dilapidated, leftover office furniture acquired when other faculty or professionals on campus no longer had use for them. There was one computer for us to share, a hand-me-down that barely held together. One secretary managed everything for the entire department, and the mailroom for the entire university was housed in another building. We were responsible for making our own photocopies, but were given access to a room full of photocopiers. Faculty aren’t allowed to make their own copies in my department at Ball State.

I vaguely knew that the adjunct situation in America was horrible, but only when I began to teach as an adjunct did I begin to fully understand what a horrible racket it is.

I decided that, in addition to my full-time job, I needed to pick up some extra classes somewhere to stay ahead of the economic downturn. And it’s true that, from 2008-2011, while many Americans were losing their jobs or being forced to take furloughs or lose pay in other ways, my annual income continued to increase. But I was teaching seven or eight classes each semester, plus working with online students at Ball State to bring in extra income, too. I had the equivalent of two full-time jobs, in other words, though my overall income was not twice my full-time job’s base salary. My wife and I also needed money to renovate our kitchen; once the kitchen was finished, we could refinance the mortgage we’d agreed to at the height of the housing bubble.

How did you decide that talking about your position as an adjunct was important for your students to know about?

I only talk about the working conditions of contingent faculty when it’s appropriate, such as when a student argues that faculty salaries should be reduced in order to lower tuition costs, or when a student says “I pay your salary,” which is thankfully not something I hear much anymore. Most Americans think university faculty are raking in six-figure salaries for teaching a couple of classes each semester. I find it necessary to fight against those assumptions, which are not representative of the humanities, and certainly not English departments.

How did you tell them? Would love you to walk me through this conversation — how did you phrase things, how did they respond?

In between two of my classes—it’s important to emphasize that this exchange did not happen during scheduled class time—six or seven of my students who had arrived early were hanging out in the classroom. One of them began talking about a history instructor across the hall. The student said the class was easy, that students didn’t have to do much work, and that the teacher seemed interested in getting them to like her. I knew the instructor was an adjunct, and that she taught at several places to cobble together a living. I told the students as much, and that the class was easy because she was afraid of losing her job.

On your students’ understanding of what you were telling them — did they know the term “adjunct” before this conversation? Did they know whether their other teachers were also adjuncts?

A few of them were familiar with the term, but I defined it for them all. I said that an adjunct’s course evaluations could play a huge role in whether he or she was re-hired, and student learning did not seem to matter as much. One of the students asked if I was an adjunct. I told her I was, but only at Marian—in this Age of Google, it was no secret that I also taught at Ball State. One of them jokingly asked why I didn’t go easier on them, too. We laughed, but I told them that because this was my second job, and one I didn’t intend to keep forever, I could afford to have academic standards. “You may not like me, you may not like this class, but if you do the work I assign and make a sincere effort, you will learn something of value,” I said.

Because I considered this interaction a “teachable moment,” I made a comparison that is 100% true, though it still got me in trouble. I said that the university pays the janitor who scrapes the gum off their desks more per year than me and most of the people who teach their first-year classes. My private university students couldn’t believe that, but it was true. Even a low estimate shows how that’s true. Ten bucks per hour for forty hours a week equals an annual salary of $20,800.

One year at Marian, I taught seven courses (including a summer section), but made only $14,700 before taxes. It was three-fourths of the work of my full-time job at Ball State. I would have made nearly double that amount for teaching seven classes at Ball State, based on my then-current salary. And Marian isn’t the worst of the bunch—a few schools in the area still pay adjuncts less than that per credit hour. It’s shameful.

What happened next? Would love to hear more about the student who brought this to the administration.

I didn’t think anything of it at the time—in no way did I think I’d done something wrong by speaking the truth. But 10 days later, my boss wanted to meet with me about a “classroom incident” that had been reported by another faculty member. This other faculty member reported that a student had come to him for help because I had “ranted” about the low pay and working conditions of adjuncts to my students.

I’m not an idiot, but I didn’t immediately recognize that one of my older students shared a last name with a Marian professor who worked in another department, and she was one of the students who participated in this discussion before class. I only knew his name because he sent dozens of emails each semester to the faculty list. The student who supposedly came to him for help was his wife—she told him what I said and it upset him so much that he felt he needed to report me. Again, I didn’t take up class time. This discussion happened before class. And all I did was tell the truth. The kicker? This guy who tried to get me in trouble probably still has an appallingly low salary, too, even for a tenured theater professor.

Teaching in the humanities is like being in The Hunger Games. The odds are never in your favor, and your best bet is to run like hell in the other direction. But if you do get caught up in the fight, you’ll be fighting for scraps. There are no winners.

My boss was especially worked up about the janitor comparison. She wanted to know how I could possibly make that claim.

A day or two before my boss called me into her office, my wife had worked up some budget numbers for the next year. She told me I didn’t need to keep working at Marian—we’d already renovated the kitchen and refinanced, and most of my income from the third year in this position was in the bank. So while I calmly explained to my boss the realities of adjuncts at Marian and across the country, and then argued that she should work harder to improve the working conditions of the instructors under her direction, I already knew how the meeting would end.

I told her that would be my last semester at Marian. She immediately switched to a pleading, softer tone, begging me to stay. I’ll never understand that. She had hit me up for all kinds of free consultations about curricular design—the Writing Program at Ball State had won a big award for our curricular overhaul, and I had played a part in making that happen. The program at Marian was very much out of date, by 20 years or more. Maybe that had something to do with her pleading. Or maybe the only thing worse than a troublemaking adjunct is having to go through the process of hiring his replacement.

Do you think the rise of contingent labor affects student outcomes?

Maybe. I think it’s an easy assumption to make. “Contingent labor” is a broad term. Salaried, full-time employees with benefits—especially those whose one-year contracts have been renewed multiple times—probably feel like they can do more to challenge students and keep high standards. Adjuncts living from class to class might not always feel like they can do that. But are tenure-track faculty better teachers? No. Absolutely not. Obviously, there are good, bad, and mediocre teachers in every department, whether they’re adjuncts, contract faculty, or tenure-track faculty. But some of the best teachers I’ve known have been salaried, full-time instructors off the tenure track.

Now, because of my administrative position, I have a (reduced) teaching load of three courses per semester, the same as most tenure-track faculty in my department. I still write and publish. I still write letters of recommendation for students and colleagues, serve on committees, and everything else. But my base salary twelve years after I started my full-time job is two-thirds of the starting salary my department just offered a tenure-track hire who has almost no relevant teaching experience and no book publications. Departments and universities are afraid to promote contract faculty because they think it will open the door for them to pay everyone a decent salary, adjuncts included. But the research shows that tenure-track salaries are tied to contingent salaries in interesting ways. A rising tide lifts all boats, but too many tenure-track faculty think it’s an us vs. them situation. Universities are being gutted from the inside out by state legislators and those who think “running it like a business” is the best strategy. A recent article in the Indianapolis Business Journal praised my university for its low faculty pay, and didn’t say much about how our recently departed president was paid nearly a million dollars last year. Her base salary was lower than that, of course, but after bonuses and the rest, it totaled close to a million dollars. And this is at a public university in Indiana, one without a medical school or law school.

In my experience, adjuncts are really reluctant to talk with students about their work/contract circumstances. Why do you think this is? Did you feel this way in the past and change your mind, or…?

Adjuncts are afraid to speak up for fear of losing their jobs, and universities play on that fear. Tenure-track faculty have their own fears, of course, and in general, I think faculty across the humanities are afraid to demand better pay and working conditions. I have never been afraid to speak up, but look what happened when I did—I was reprimanded for telling the truth, and not even in an especially inflammatory manner. I had the luxury of leaving that position, so it didn’t matter. But what if I’d needed every last one of those 700 dollars per credit hour? What if, as one of my colleagues there did, I had to teach at five different universities all over the state just to get by? I imagine I’d have to act like that colleague, who was defeated and quiet, and who most closely resembled a ghost floating in and out of campus.

I spent last year researching faculty pay for a proposal that asks the university to increase the salaries of contract faculty in my department. I knew the starting salary for my position hadn’t been raised since I started, and that cost-of-living raises during the last 5-10 years had been few and far between, even for faculty who were deemed “meritorious,” as I was. I errantly thought that was just the situation at all universities. But it’s not, I discovered. My university has a list of 21 peer institutions, and 14 of those institutions responded to my inquiries about starting salaries, titles, and course loads for non-tenure-track faculty who teach writing courses. I was ashamed, and then angered, to learn that the median starting salary at these institutions was exactly equal to my current salary. Because I’d been deemed meritorious for more than 10 consecutive years, I should have received the highest annual raise of any contract faculty member in my department during each of those years. Indeed, the only contract faculty who make more than me now are those who’ve taught in the department for 20 years or more. That’s the only way to get a higher salary: grind it out for two or three decades.

Meanwhile, the contingent labor force is becoming more qualified than ever. In some departments, the contingent faculty may be as qualified—or more qualified—than those on the tenure track. As this continues, departments will have to find more equitable ways of compensating their employees. The old way of thinking about contingent labor is that they’re temporary teachers who, if they’re any good, will move on in a year or two to a better position. But that hasn’t been the case for the entirety of my professional career. There just aren’t enough tenure-track positions. Creative writers, in particular, are not going to stop writing poems, essays, short stories, novels, and screenplays just because they have a teaching job off the tenure track, even one with a heavy teaching load, and when those creative works are published, some of them to wide acclaim, the balance of respect and recognition may begin to shift within English departments.

Another factor is location. I’m qualified for many tenure-track positions in creative writing, but my wife and I bought and renovated an old house in Indianapolis that we love. We want to stay here. We are deepening our roots in our home state by choice, not because we don’t have better options. Some people say, well, why don’t you leave academia? Believe me, I think about it every year. I love teaching, but it’s hard to respect yourself when the institution you work for so clearly doesn’t respect you. Because so many Americans assume college professors have the easy life, it can also be difficult for professors to transition to positions outside academia, but it’s not impossible. Your CV might be fat-packed with accomplishments, but if you’re in a non-tenure-track position, there’s a low ceiling and few opportunities for advancement. Try to shuffle sideways into another career and you might find that those interviewing you don’t understand why you’d ever want to leave your “cushy” academic gig. The choice to attend graduate school, especially if your intention is to one day teach college courses, has never been riskier, especially if you take out student loans to do so.

January 31, 2015

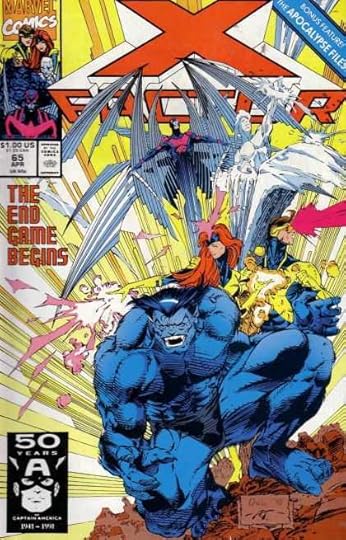

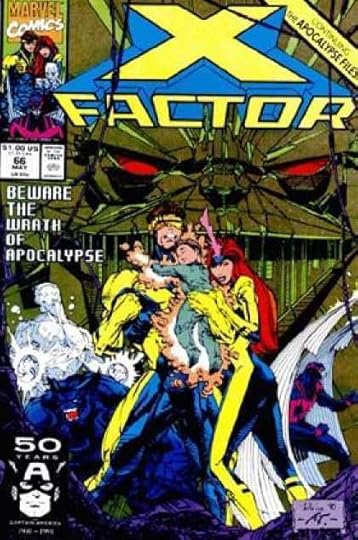

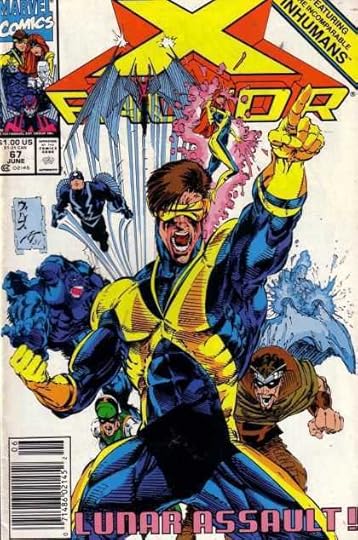

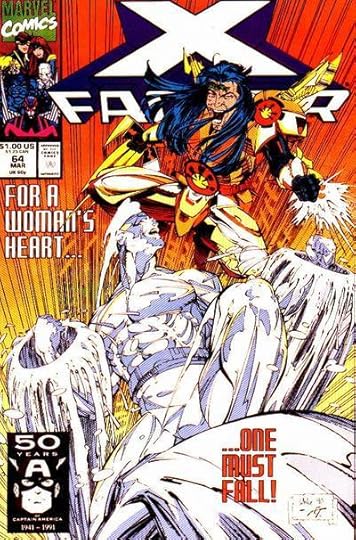

Covers from Whilce Portacio’s run on X-FACTOR. Can’t...

Covers from Whilce Portacio’s run on X-FACTOR. Can’t believe these issues aren’t available through Marvel Unlimited.

December 28, 2014

"Something I’d like to tell the writers just beginning, who worry if they can make a go of it under..."

- An essay I wrote for The Huffington Post on art and the family narrative: (via mayhewbergman)

Andrew Scott's Blog

- Andrew Scott's profile

- 9 followers