E. Amato's Blog: Zestyverse

October 20, 2016

Dear Able People: An Ableism Primer

Dear Able People:An Ableism Primerby E. Amato

Dear Able People:An Ableism Primerby E. AmatoBeing differently abled can be a minefield. Daily life activities can be filled with frustration, fear, loneliness, pain, adaptation, challenge, and/or plain impossibility. To get through the day, people with ability issues need persistence, patience, flexibility and focus – many of which tend to be in short supply due to illness, chronic pain, mental health issues, and injury.

Still, life goes on, and people with ability challenges do remarkable things. Though blinded in a shooting incident in his twenties, theatre artist Lynn Manning toured shows around the world. Stephen Hawking has changed humanity’s conception of the universe from a wheelchair with a voice simulator. In London in 2012, a Paralympian zoomed past me on prosthetic legs.

Differently abled people find ways to get through the day, to become new selves, to express their gifts, and to thrive in circumstances that would make many people want to give up. This is what life should be – a journey of purpose to happiness, despite the odds and challenges on the path.

What life shouldn’t be is degrading, shaming, shunning, penalizing, and punishing. Yet every day, people who are differently abled face these in varying degrees. From micro-aggressions through job discrimination, able-bodied people bring consequences to disability that don’t have to be there.

We call this “ableism.”

We find it both harmful and unnecessary.

Perhaps you haven’t realized that this problem exists or know how it manifests. Here’s a quick overview of the problem, some of the issues, and some fixes.

1. What is ableism?

Ableism is the practice of assigning less value to persons who have disabilities.

Ableism can take many forms, including hurtful speech, denigration, rendering invisible or unseen, or not taking practical needs and parameters into account.

Ableism can be as small a gesture as side-eye to the life-damaging hiring discrimination. It removes agency from individuals.

Ableism can be unconscious; for example, making assumptions about ability, capability, and mobility without creating an environment that allows for people of different levels of ability.

Ableism can take the form of the enforcement of “normal,” while discrediting those who fall outside this arbitrary assignation.

2. What is disability?

Disability is any state of not being 100% healthy in body and mind. It can be temporary, chronic, permanent, or, in some cases, terminal. It can be related to an illness or debilitating treatment or side effects from medication. It can be the result of an accident or injury. It can be the loss of physical mobility or the use of senses such as sight and hearing. It can be related to psychological health or an autoimmune condition. It can be any combination of the previously mentioned conditions. It may or may not be visible to you.

3. What is invisible disability?

So glad you asked! Not all disabilities are visually evident. Let me state this again: notall disabilities are visually evident. This is so important. People suffer from many types of illnesses, diseases, injuries and mental health conditions. Not all of these require wheelchair, cane or crutches. Not all of them are on display.

This does not mean the person you are looking at, who is able on the outside, is actually able. If they have requested assistance, if they are parking in a handicapped spot and have a handicapped placard, then they are handicapped as far as you are concerned. They don’t need to be questioned by you or reminded that it’s a handicapped parking space. They don’t owe you an explanation. They could have hearing problems, they could have a condition like lupus or fibromyalgia that can render movement painful. They could have a serious mental health issue. They could have a brain condition that makes balance difficult.

It doesn’t matter -- none of the above matters. What matters, is that they are not able, even if their disability is not visible to you. What matters is that it’s their body, which they live in and know intimately. They do not need to share their body and its processes with you if you are not their practitioner, caregiver, or very best friend in the world.

They do not need to be shamed, punished or penalized for their appearance of health. They are struggling. If you are making their way in the world harder, then you are policing their behavior and needs, which is no one’s place. Instead, try Plato’s advice: “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a harder battle.”

4. What does ableism look like in the world?

In a fantastic open letter, Samantha Cleasby details a trip to the disabled bathroom marked by being “tutted” at by another woman. She is candid about her disability and her needs. Her medical condition essentially means she has no bowel. Cleasby still appears able – she is not in a wheelchair, she is able to run to the bathroom as soon as she realizes she is about to have a problem. These should be positives, but they leave her open to criticism, jeering, and even laughter.

Imagine this level of scrutiny every time you went to the bathroom outside your home. Now imagine living with pain, limitation, digestive issues, mess, anxiety about having accidents in public places, in addition to this level of scrutiny. It seems more than unfair – because it is.

A person who is differently abled may experience this type of encounter multiple times upon leaving his or her own home every day. The additional friction and tension of potentially difficult human interactions placed onto already overloaded physiological systems are unwelcome and can be damaging.

Most people who are differently abled learn to be up front about boundaries and limitations. This doesn’t mean they are going to tell you their health problems, but they will offer up what they can or cannot do when it’s applicable. Yet, this does not always produce the desired results. Refusing someone access to alternatives to stairs, or refusing to lower a bus when requested are ableist actions. Assuming that disabled people are lazy, rather than accepting that they are limited in certain areas, or in pain at that moment, or sometimes, or all the time is ableist.

Forcing people to beg in order to honor the limits of their own bodies, for your listening and understanding, or for you to give them what they need when it is completely within your power to do so is ableist. It is tiring to live with ability challenges; it is exhausting to continually explain, charm, cajole and plead for simple modifications.

Ableism looks like judging people by how you think they look, and what you think their level of ability should be – not what it actually is.

5. What does ableism look like in the workplace?

Ableism at work can include harassment, making jokes, and overlooking in favor of able colleagues. Ableism can take the form of not accommodating necessary modifications to workspaces or schedules for those who are differently abled.

Firing an employee while he or she is out on disability, or passing over those who have been ill or have struggled with mental health issues for promotions is ableist. Actions like these have major consequences on income, financial stability, and threaten consistency of access to health care.

Although the U.S. and other governments have strict codes and guidelines for persons with disabilities, these are not always fully honored, and the burden of proof is on the employee. In extreme situations of ableism, an employee will be forced to retain legal counsel and sue for his or her rights, either after termination, or while still maintaining a working relationship with colleagues and the employer. Suits like these are time consuming, anxiety producing, and draining. The multiple stresses to body and mind of unemployment, loss of income, harassment, loss of access to or increased cost of health coverage, added to the burdens that come with ability challenges can be devastating.

6. How can I help?

You are helping just by reading this! You are learning about ableism, disability, and its impact on lives – that’s very helpful.

You can help by not policing the behavior or stated needs of people with disabilities. You can help by accommodating those needs respectfully when possible. You can help by beginning a conversation around these issues with other able people.

You can help by listening to, learning and adopting the language used by the differently abled people you know. Alternately abled people have a variety of ways of referring to themselves and their condition. They usually settle on terms that give them the greatest agency. By accepting the language being used, you are reinforcing their personhood. When you choose other language, language that is debilitating or disempowering, you are overwriting the choices made by the person with whom you are interacting, which is tantamount to making them invisible, or infantilizing them. If you don’t know the proper language to use, ask. An open-ended, non-judgmental question is always welcome. It shows you are listening and you care. Be brave – the person you are talking with is, so you can be, too.

Finally, you can help by remembering that no one is infallible and everyone will have struggle or illness in their lifetime. Differently abled people are you, in a different body at a different time – treat them as you would love to be treated yourself if these were your circumstances.

“

…unapologetic feminist, dulcet-toned poet, activist, film-maker, editor of Zestyverse

” (LossLit) E. Amato is a published poet, award-winning screenwriter, and established performer. She has published three poetry collections

“

…unapologetic feminist, dulcet-toned poet, activist, film-maker, editor of Zestyverse

” (LossLit) E. Amato is a published poet, award-winning screenwriter, and established performer. She has published three poetry collections through Zesty Pubs and is a freelance writer and editor, and a contributor to

The Body Is Not an Apology

. She got Marmite in her bag.

through Zesty Pubs and is a freelance writer and editor, and a contributor to

The Body Is Not an Apology

. She got Marmite in her bag.

Published on October 20, 2016 05:33

August 25, 2016

Dear Able People: Creating A Relationship That Transcends Ability Issues by N.S. Lavay

Photo courtesy N.S. Lavay

Photo courtesy N.S. LavayDear Able People:

Creating A Relationship That Transcends Ability Issues

by N.S. Lavay

What is it like being in a relationship with somebody who has severe mental health needs?

I think it’s probably a lot like any other relationship. We spend Sunday sitting on the couch watching Netflix and eating chips. We listen to crappy music together and debate the merits of different brands of peanut butter at the grocery store.

We also have a very unique set of challenges.

My fiancée, who I call ‘Goose,’ has been diagnosed with chronic PTSD. This creates certain difficulties, but through our teamwork we’ve navigated these challenges and come out stronger. I’d never tell anybody I’m a relationship expert but we just set a date for our wedding; as a commitment-phobe who’s not running away screaming, I assume we’re doing something right.

It took time to figure out how to be a good partner, but I’m very glad I’ve had the luck to meet the incredible individuals who’ve helped me understand how crucial honesty, communication, respect and trust are in fostering a healthy relationship -- regardless of mental health. I recognize that it’s important to learn from my previous relationships. Critical reflection has helped me discover what I don’t want to put up with from others, and realize my own missteps as well.

In my first relationships, I found honesty and communication especially scary. Goose is amazing at gently pushing me towards straightforward discourse and setting boundaries. Not too long ago, I was afraid to discuss my needs, but she’s shown me that it’s okay to tell her when she does something that annoys me, like stealing my pajamas every night. It’s okay to confess that staying in for three weekends in a row is slowly eating at my soul. Being honest is good — I deserve warm pajamas in our cold apartment and I shouldn’t silently develop cabin fever.

Time has taught me that advocating for my needs creates openness between us. Being able to talk about little things which annoy me is practice for talking about the issues that scare us. If I can’t ask Goose to stop stealing my water, how can we talk about bigger issues such as our plan for a mental health crisis?

Trust has been an interesting issue for me. Most people think of cheating when the word ‘trust’ is thrown around, but for the first ten months of living together, I found myself adopting this horrible caretaker approach to our relationship. I made Goose’s lunches, did all the laundry and the grocery shopping, all because I wanted her to be happy and comfy. After a string of weekends on laying on the couch feeling grumpy and irritated, I realized that I didn’t trust in her ability to take care of herself, and this attitude led to burning out. I genuinely enjoy taking care of others regardless of ability, but when I’m stressed I forget to take care of myself. There’s nothing worse than feeling exhausted and emotionally drained, only to be hit with a mental health emergency. It’s important that I trust her to make the best decisions for herself, because when she does request my help, I want to be ready for when she needs me the most.

I won’t lie about the fact that PTSD influences our couple time. We can’t go to the movies, ride the bus at night or go crowded places. While these are things I miss, it means we go on unique and thoughtful dates. We’ve gone to secluded beaches, mini golf, and hiked while holding hands. A therapist suggested we take a dance class so we could experience a safe way of being in a crowd. One of my favorite activities is picnicking at the park with a game of Scrabble. I’ve also found that these types of activities allow us to interact with each other, which is more difficult when one is plunked down in front of a screen or nursing a beer in a loud bar. This has helped me feel so much closer to my love.

If I want to do anything Goose feels uncomfortable doing, like going to bars or dancing, I save it for my friends. This means I get to explore the city I live in with my other favorite people, and have partner who feels safe and mentally balanced.

The PTSD directly influences date-night choices. It also influences our arguments. Goose navigates couples issues much better than I because she was lucky to have received the help she feels she needed. A variety of mental health experts helped her develop a set of tools to evaluate emotions and communicate during arguments. She’s able to ask critical questions needed during times when we don’t see eye-to-eye. Goose has the ability to stay grounded and ask, “Why are we arguing in this moment? What are we trying to accomplish with this argument? How are we feeling? What’s the appropriate way to talk about that?” She’s been an amazing example regarding communication during disagreements. Thanks to my partner, we can find solutions without hurting each other’s feelings. We usually come out of disputes feeling better about the issue at hand and even stronger as a couple.

Being with her can be challenging, but all relationships have their moments. For me, it’s been about deciding whose issues I’m most willing to handle.The magnetic connection I felt during our first conversation has never gone away and every day I only feel more drawn to her. The swelling in my heart when I look into her gorgeous eyes always throws me off guard. I recently accidentally saw Goose in a wedding dress she was trying on, and the sight of it nearly knocked the breath out of me.

Everybody has problems, including able-bodied and neurotypical people. Regardless of ability or mental health needs, everybody has strengths and weaknesses. Mine work well with my fiance’s. The difficulties we face together are nothing compared to our determination to overcome them. I love her so fiercely that we’re willing to do whatever it takes to stick together. Goose attends therapy and engages in other activities to stay on top of her mental health, while I proactively eliminate triggers, or stay in with her on anxious nights. At the end of the day, I’m content from the time we spent together during the evening, and obsessively imagining the details of our wedding, which I bug her about as she attempts to fall asleep. Sometimes she asks me how I can put up with anxiety and avoidance of loud noises, but I always tell her it’s a very small price to pay if I want to watch crappy Netflix with her when we’re 105.

N.S. Lavay is an art historian and writer currently existing in San Francisco. Read more work here, or follow her on instagram.

N.S. Lavay is an art historian and writer currently existing in San Francisco. Read more work here, or follow her on instagram.

Published on August 25, 2016 01:27

June 6, 2016

Women You Should Know - Gina Psyliakou by Aradhana Kothari

Women You Should Know:Gina Psyliakouby Aradhana Kothari

I used to work for a service that offered support to disadvantaged and vulnerable young people. The difficulties with the job were the usual barriers - unsociable hours, insufficient budgets, infinite reserves of resilience needed, and the ability to withstand verbal abuse - that came hand in hand with working with young people who had been dealt the hard end of life.

Standing in my office on an unremarkable day, a staff member comes into the room. Striding in slow motion, stopping with the superhero stance that befits her most recent actions. This woman has just achieved something outstanding. You know it; she knows it; everybody standing in this ridiculously small office knows it. But of course, she doesn’t. The Foo Fighters play as she moves casually past, in sync with all of the words. The one lyric I can’t help hearing is: “There goes my hero, he’s ordinary.”

This is where my heart resides: in the ordinary heroes. The action of getting up everyday and trying to make the world a better place, purposefully. The global citizens who have the empathy to act without pride, greed, and ego-governing. Making small changes and meeting challenges with the faith and belief that you can make a difference; continually fighting, often without acknowledgment or acclaim.

Gina Psyliakou is an everyday heroine. Born in Greece, Gina came to England in October 2000. Studying graphic design, then changing her focus to Humanistic Therapy. Moving back to Greece in 2014, Gina continued to work supporting vulnerable people, and currently works with refugee children. Now she is a “Friendly Space Facilitator” with Praksis in association with Save the Children.

What is it that you do as a Friendly Space Facilitator?

We’ve created a space within the refugee camp where children can play, learn and regain their sense of carelessness. We work with the children of refugees providing them a safe space where they can play, gain a sense of normality, overcome the trauma of war and hardships and build their resilience in order to survive the harsh reality they are living in. Those spaces are important for the camp because they bring a sense of normality and joy within a very dire environment. I am based in Chios Island ... next to Lesvos and [it] has big numbers of refugees arriving.

What originally inspired you to work with disadvantaged young people?

When I was studying in Banbury... there was a lot of talk about young people and their behaviour. The ASBO [court] order had started being served to young people that were antisocial according to the government. It felt like young people were being criminalized for being young and for the failures of their parents, their schools, their governments and society in general.

This made you want to get involved?

I started working as a graphic designer, campaigning to start inspiring young people to believe in themselves to have a dream. I felt that they had lost their way, and had no one to guide them. They were just reacting in a world that we had created that wasn’t okay. The world wasn’t inspiring them to be the best they could be. By the time I finished my degree I realised that I wanted to work more with young people and support them directly.

So after Banbury where did you start with your newfound passion?

I went to Brighton and I found my first volunteering position, which changed my life forever. The Young Peoples Centre is for young people that have been isolated from society, and are unloved and wounded. Here is where they can find a place they can belong and be themselves. Where they are accepted and cared about. It is an inspiring place that has taught me so much.

What would you say was your biggest lesson at the Young Peoples Centre?

[T]o support a young person you have to empower them and teach them how to do things for themselves. Help them believe in and understand themselves enough to be able to tolerate failure and keep going. And never, never give up on them, no matter how many times they fail. We, as professionals, representing sometimes the supportive parents these kids never had, we have to be consistent, honest, fair and forgiving.

Tell me who has inspired you in your work?

The people that inspired me where those who challenged me in my work, by making me reflect on my behaviour and [taking] the time to teach me. I have also learned a great deal from the young people I worked with over the years and especially those who had horrible unloving childhoods, but still had a big capacity for love and forgiveness.

What things in your opinion should we have in mind to live better lives for ourselves and others?

That’s a big discussion, but three things that I believe would make a big difference and bring a domino effect are: living closer to nature, strengthen our sense of community and eliminate competitiveness. I believe there is a big void within us by living away from nature that cannot be contented with anything else. That sense of humility you feel in nature and the connection to everything around you, gives you a sense of peace and balance, something that we’re denying ourselves by putting us above nature.

Secondly, I feel that isolation is one of the big issues in the western world; individualism is overrated. We are social beings; we don’t develop without connecting to others, so we need a feeling of community and solidarity in order to survive.

And lastly,... [I think that] competition should only be acceptable in sports and even there up to a point. We should strive to better ourselves in everything we do and work with each other for the common good, not individual prosperity only.

Gina is an agent of change, fighting for a better world for herself and those around her, where optimism is fast becoming a precious commodity. Reminding us to power forward by walking, sauntering, stumbling or crawling, because it will be worth it in the end.

Aradhana Kothari is a former Youth Worker and Community Development worker (although the role never really escapes you). Living nomadically at present trekking high mountains and diving deep seas Aradhana is enjoying the exploration of new cultures, tastes of new food and constant challenges on her understanding of the world.

Aradhana Kothari is a former Youth Worker and Community Development worker (although the role never really escapes you). Living nomadically at present trekking high mountains and diving deep seas Aradhana is enjoying the exploration of new cultures, tastes of new food and constant challenges on her understanding of the world.

Published on June 06, 2016 00:00

April 19, 2016

Women You Should Know - Lisa Leone by Jessie Florence Jones

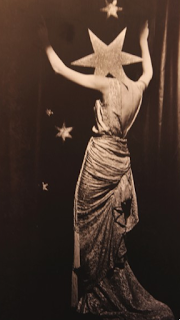

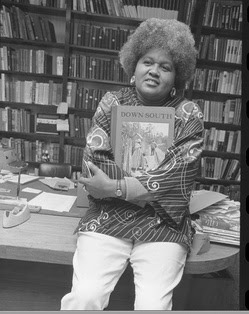

MJB by Lisa LeoneWomen You Should Know:

MJB by Lisa LeoneWomen You Should Know:Lisa Leone

by Jessie Florence Jones

When it comes to strong women, hip-hop doesn’t often open its doors very widely. Almost everybody has heard of Nicki Minaj, whose hard-hitting, empowered raps broke through an industry perpetually dominated by men. Perhaps even more have sung the praises, or bathed in the light of the artist Mary J Blige. Apart from performers like these, hip-hop can be a minefield for women. A rare exception is Lisa Leone, a photographer who has spent her career documenting the aforementioned Blige, Nas, and Snoop Dogg to name a few. Hailing from the Bronx, Leone started her career by photographing musicians, and eased her way into cinematography, shooting videos for the likes of D’Angelo and TLC. Like Bibi Bourelley (the woman behind a lot of Rihanna’s smash hits), Leone has a long list of accolades that would suggest she belongs deeply nestled into the public’s address book of hip-hop. After working on Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick became her mentor, which is visible in her black and white shots. The contrast of grit and delicacy in her monochromatic stills remind me of Kubrick’s Lolita, blending the disturbing with the beautiful. This is something that makes Leone so important in my eyes; not only has she photographed many household names, but she also has a unique ability to take such huge stars and make them appear vulnerable and human. Though often depicting artists performing or in the studio, there is a constant sense of candidness, the photographer’s presence seemingly absent. They don’t appear staged or forced, simply a personal peek into the lives of these artists. Her photographs are an invitation to spend some down time, away from the expected decadence, with these stars, depicting them as intimately and genuinely as possible.

Nas by Lisa Leone

Nas by Lisa LeoneLeone has expanded her work to film, with a number of titles under her belt as cinematographer, writer, and director. Her debut short Exactly was shown at both the Sundance and Tribeca film festivals. Since then, she has directed, or co-directed, four films. In 2014 she released Here I Am, a collection of her photography portraiture. The title reflects the struggle and hard work that involves surviving such a male-dominated arena, to become a name on the tip of everybody’s tongue. As recording artists such as M.I.A and Azealia Banks and others build on the legacy of early women in the art form like Leone, the creation of a distinctly female sphere of hip-hop becomes a reality.

Jessie Florence Jones 22 year-old student based in Leeds currently doing an Erasmus year abroad in Berlin studying English Literature. Was formerly Fashion Editor at the Gryphon, the university newspaper, and have had my illustration on crownrules website.

Jessie Florence Jones 22 year-old student based in Leeds currently doing an Erasmus year abroad in Berlin studying English Literature. Was formerly Fashion Editor at the Gryphon, the university newspaper, and have had my illustration on crownrules website. Editor's Note: We have so many pieces, we've gone past Women's History Month! You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Published on April 19, 2016 05:16

March 27, 2016

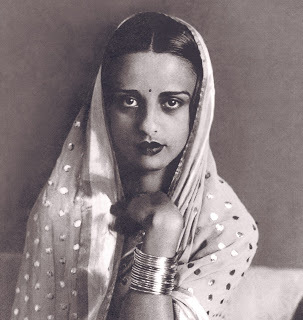

Women You Should Know - Amrita Sher-Gil by Nicole Lavay

Women You Should Know:

Amrita Sher-Gilby Nicole Lavay

I’ve always loved art history, but never so fiercely as when I was a teenager. I grew up in a conservative suburban community where my pink hair and black clothes made me an oddball. My love for the arts and women didn’t help me fit in either, but it was okay, because I’d discovered something more interesting than the life around me: the lives of 19th and 20th century artists.

I took Advanced Placement Art History, where I excelled. The tales of Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Warhol all excited me so much. These were people who moved to big cities, had large circles of artistic friends, went on adventures to foreign lands and then used their experiences to create something new and change the world.

My text book contained hundreds of pages on art from Europe, mostly by white male artists. Women artists didn’t appear in groups of more than two per chapter until modernism, and I found their biographies and the representation of their art lacking. The definitive canon of art history I was shown in high school neglected the female artists I’d later come to love.

The lives of real women artists were never presented to me as interesting or exciting. Luckily, I went to a college where I received the education I needed to understand that women artists are creative, capable, smart and just as bold as I’ve always wanted to be. I was given the tools to discover artists I could relate to. The biography of Amrita Sher-Gil caught hold of my mind, and lately, as I try and navigate the path to forging my own creative life, I find myself inspired by hers.

Born in 1913 to an Indian father and a Hungarian Jewish mother, she spent her unique childhood between Europe and India, completing her artistic training in Paris. She painted self-portraits of herself, nude, which was just as scandalous in the 1930’s as putting nude selfies up on the internet is today. Sher-Gil chose to paint portraits of herself and her sister honestly without ‘oriental’ details, as other Indian artists catering to the European gentry did. I love thinking about Sher-Gil, so radical at age 17, giving no fucks, and confronting racism and sexism in the arts by depicting herself as an ‘average’ subject, rather than as an oriental fantasy from a far away land. The independent young artist found a place for herself in bohemian Paris. She caused quite a stir through her artistic feats, and in her personal life, as she was known to wear her sari and conduct affairs with both men and women.

Sher-Gil won national competitions, and her incredible skill was promising, but her mixed-race heritage set her apart from her contemporaries during the dusk of European colonialism. Never one to choose conventionality, the artist said ‘good-bye’ to the capitol of the art world and began her career in India, where she painted with the celebrated revolutionaries of the Bengal School of Art.

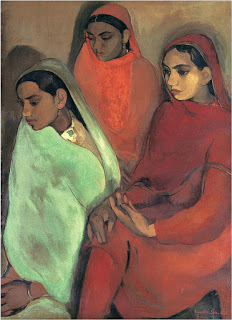

Her return to India brought an immediate shift in her artistic style, and her subject matter, too. She spent 1937 touring rural southern India, finding inspiration in the daily lives of local women. She began painting village scenes, group portraiture, and images of average Indians, especially those living in poverty.

Her new work was a reflection of the changing Indian political landscape, as the colonized people demanded independence from the British. Her paintings explored Indian identity on a national level. Sher-Gil didn't orientalize or romanticize the lives of villagers living in poverty. She painted the lives of women, without sexualizing or romanticizing her subjects. These women, who break away from European beauty standards are not on display or eroticized for the gaze of the viewer. They are strong, sturdy, grounded, almost defiant.

Unfortunately, only four years after her return to India Sher-Gil died at age 28, after slipping into a coma from a hemorrhage suspected to be the result of a botched abortion. Her untimely death came just days before the opening of her first major solo exhibition in Lahore.

Amrita Sher-Gil was a masterful painter whose amazing technical skill wowed critics. Her legacy lies not only in her skill, but in her revolutionary choice to paint the average Indian during the fight for independence and represent women at the beginning of the women’s rights movement. Adventurous, bold, and self-determined, Sher-Gil is so awesome it makes me incredibly sad that she’s virtually unknown by Western audiences.

Sher-Gil fearlessly asserted her identity again and again throughout her life, defying convention and breaking barriers, both in her personal life and career. She lived an artistically rich life full of adventure; looking at her art reminds me to live life without creative limitations.

Nicole Lavay is an art historian, educator, writer, and photographer based in San Francisco. She has worked at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, and recently taught English with the Académie de Nantes. She currently spends her time traveling, learning new languages, and trying to read as many books as possible while preparing to work in South Korea.

Nicole Lavay is an art historian, educator, writer, and photographer based in San Francisco. She has worked at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, and recently taught English with the Académie de Nantes. She currently spends her time traveling, learning new languages, and trying to read as many books as possible while preparing to work in South Korea.Editor's Note: I'm so grateful to find out about Amrita Sher-Gil's life and work! If you liked this piece, you can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Published on March 27, 2016 00:00

March 24, 2016

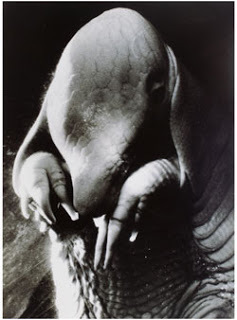

Women You Should Know - Dora Maar by Elizabeth Iannaci

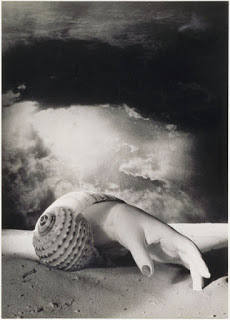

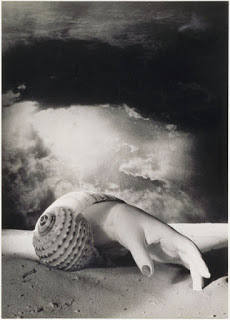

I don’t remember where I first came across Dora Maar’s Portrait of Ubu: Most likely it was in one of the dust-drenched used bookshops that dotted the Hollywood Boulevard of my youth – I’d stroll in on my walk home from junior high, get lost browsing the disheveled columns of faded clothbounds stacked floor-to-ceiling.

I don’t recall where. But I do remember the image that somehow made my chest tight, yet, like a loose tooth, I couldn’t leave it be – had to keep touching it with my tongue. Ubu held a tender mystery that entered through my eyes but set up shop somewhere deep in my gut. What was it and who would take such a photo? Dora Maar took this photo in 1936, and it became emblematic of the Surrealist Movement. Presumably to preserve its mystique, she never confirmed what Ubu actually was.

Years later, I learned that many of the images I held as icons of social, artistic and sexual independence were also works by Dora Maar. Their audacity and wit were embraced by my free-thinking, unfettered generation.

No surprise that Maar’s images were standard-bearers of the Surrealists (though there were formally no females among the Surrealists when the movement was born in 1924). But I didn’t know her name the way I knew other photographers of the period, like Man Ray or Dorothea Lange.

Dora (Henriette Théadora Markovitch) began her artistic life at 19, moving back from Buenos Aires to her hometown of Paris and enrolling in the Academié Julian which offered the same training to women as they did to men(!). She pursued both painting and photography, but early success as a photographer pointed her firmly in that direction. Drawn to the contrasts and disparities of street life, she gave her subjects what she recognized in them—grace and dignity: blind beggars, street waifs, a friend lost in thought. This sensibility manifested itself in all her work: portraits, the Surrealism of the streets, and especially with the groundbreaking images in her photomontages. Even the striking fashion and commercial photography that provided her living had an edge.

Dora (Henriette Théadora Markovitch) began her artistic life at 19, moving back from Buenos Aires to her hometown of Paris and enrolling in the Academié Julian which offered the same training to women as they did to men(!). She pursued both painting and photography, but early success as a photographer pointed her firmly in that direction. Drawn to the contrasts and disparities of street life, she gave her subjects what she recognized in them—grace and dignity: blind beggars, street waifs, a friend lost in thought. This sensibility manifested itself in all her work: portraits, the Surrealism of the streets, and especially with the groundbreaking images in her photomontages. Even the striking fashion and commercial photography that provided her living had an edge.

With all of that to commend her, if you Google Dora Maar, the first entry will probably state, she is most widely known as Pablo Picasso’s muse of nearly a decade (beginning late 1930s).

She met Pablo Picasso on the set of Jean Renoir’s film Le Crime de Monsieur Lange and then again, famously, at café Les Deux Magots in 1936. That meeting changed forever the focus and trajectory of Dora’s life. Her beauty and daring fascinated him (she was said to have cut her fingers playing “the knife game” at a café table when he met her). They were drawn inevitably to each other. She moved around the corner from his studio: he stayed with her often, and though he reportedly displayed on a shelf her bloodied gloves from their Deux Magots encounter, she was never allowed into the studio without his invitation.

The pair became an influential part of the Surrealist Movement; they collaborated on a number of artistic projects together and with other prominent artists, including Man Ray. She had her first solo photography exhibition in Paris. She became a regular model for his work. Picasso encouraged her to leave photography and take up painting again (some say after he belittled her photographic talent). She did. Friends said that she would sacrifice anything for him. According to Maar herself, I wasn’t Picasso’s mistress; he was just my master.

For Picasso, she was the woman in tears: beautiful and sad—sad, he said, because she was barren and suffered for it. Weeping Woman and Dora Maar Seated were painted by Picasso in 1937, which is the year she documented in photos the various stages of the master creating the masterpiece, Guernica. In fact, it was said that during their time together, photographing Picasso’s work became the sole domain of Maar.

Their relationship ended tragically for Dora in 1943, when Picasso took a new lover, Françoise Gilot, who was (newer, younger, better) 40 years his junior and 20 years Maar’s. The break up sent her into a tailspin of depression, ending predictably in a nervous breakdown in 1946, after her dearest friend, Nusch Eluard, wife of the poet Paul, died suddenly. Family and closest friends gone, she felt cast aside and set adrift. So, she drifted.

Eventually, Dora found a road back, as well as solace, in Roman Catholicism. She famously told author Mary Caws, After Picasso, God. So, here’s where the tightening in my chest I experienced upon first seeing Ubu re-exerts itself, but this time, because the question is so close to home: The question is, did Dora lose herself in love or was her passion for Picasso greater than her passion for her own work? Or does it matter?

In Dora’s case, it may be that fighting her way out from under Picasso’s shadow so that the fruit of her artistic talent would be her legacy rather than her talents as a muse, was just not worth the fight. Perhaps the fight was shaken out of her along with the passion. My truth is that I don’t think it matters. The work remains and Dora Maar is a woman you should know.

Dora continued to paint (eschewing Surrealism) and to write mostly meditative poetry. She died in 1997.

5 November thought to have been written in 1970[though I’d prefer the title After Picasso, God] :

Pure as a lake boredom

I hear its harmony

In the vast cold room

The nuance of light seems eternal

The soul that still yesterday wept is quiet -- it's

exile suspended

a country without art only nature

Memory magnolia pure so far off

I am blind

and made from a bit of earth

But your gaze never leaves me

And your angel keeps me.

Elizabeth Iannaci holds an MFA in Poetry, lives in Los Angeles, remembers when there really were orange groves, and shares birthdays with Red China Julie Andrews and Bonnie Parker. She has traveled extensively in Europe and Asia without getting arrested (please knock on wood), and can usually find out how to ask Where is the bathroom/water closet/ toilet/facilities? She also writes poetry and occasionally writes letters on real paper, delivered by humans.

Editor's Note:

Thanks so much to Elizabeth for sharing her wonderful writing with us and for this reconsideration of Dora Maar. You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Elizabeth Iannaci holds an MFA in Poetry, lives in Los Angeles, remembers when there really were orange groves, and shares birthdays with Red China Julie Andrews and Bonnie Parker. She has traveled extensively in Europe and Asia without getting arrested (please knock on wood), and can usually find out how to ask Where is the bathroom/water closet/ toilet/facilities? She also writes poetry and occasionally writes letters on real paper, delivered by humans.

Editor's Note:

Thanks so much to Elizabeth for sharing her wonderful writing with us and for this reconsideration of Dora Maar. You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

I don’t recall where. But I do remember the image that somehow made my chest tight, yet, like a loose tooth, I couldn’t leave it be – had to keep touching it with my tongue. Ubu held a tender mystery that entered through my eyes but set up shop somewhere deep in my gut. What was it and who would take such a photo? Dora Maar took this photo in 1936, and it became emblematic of the Surrealist Movement. Presumably to preserve its mystique, she never confirmed what Ubu actually was.

Years later, I learned that many of the images I held as icons of social, artistic and sexual independence were also works by Dora Maar. Their audacity and wit were embraced by my free-thinking, unfettered generation.

No surprise that Maar’s images were standard-bearers of the Surrealists (though there were formally no females among the Surrealists when the movement was born in 1924). But I didn’t know her name the way I knew other photographers of the period, like Man Ray or Dorothea Lange.

Dora (Henriette Théadora Markovitch) began her artistic life at 19, moving back from Buenos Aires to her hometown of Paris and enrolling in the Academié Julian which offered the same training to women as they did to men(!). She pursued both painting and photography, but early success as a photographer pointed her firmly in that direction. Drawn to the contrasts and disparities of street life, she gave her subjects what she recognized in them—grace and dignity: blind beggars, street waifs, a friend lost in thought. This sensibility manifested itself in all her work: portraits, the Surrealism of the streets, and especially with the groundbreaking images in her photomontages. Even the striking fashion and commercial photography that provided her living had an edge.

Dora (Henriette Théadora Markovitch) began her artistic life at 19, moving back from Buenos Aires to her hometown of Paris and enrolling in the Academié Julian which offered the same training to women as they did to men(!). She pursued both painting and photography, but early success as a photographer pointed her firmly in that direction. Drawn to the contrasts and disparities of street life, she gave her subjects what she recognized in them—grace and dignity: blind beggars, street waifs, a friend lost in thought. This sensibility manifested itself in all her work: portraits, the Surrealism of the streets, and especially with the groundbreaking images in her photomontages. Even the striking fashion and commercial photography that provided her living had an edge. With all of that to commend her, if you Google Dora Maar, the first entry will probably state, she is most widely known as Pablo Picasso’s muse of nearly a decade (beginning late 1930s).

She met Pablo Picasso on the set of Jean Renoir’s film Le Crime de Monsieur Lange and then again, famously, at café Les Deux Magots in 1936. That meeting changed forever the focus and trajectory of Dora’s life. Her beauty and daring fascinated him (she was said to have cut her fingers playing “the knife game” at a café table when he met her). They were drawn inevitably to each other. She moved around the corner from his studio: he stayed with her often, and though he reportedly displayed on a shelf her bloodied gloves from their Deux Magots encounter, she was never allowed into the studio without his invitation.

The pair became an influential part of the Surrealist Movement; they collaborated on a number of artistic projects together and with other prominent artists, including Man Ray. She had her first solo photography exhibition in Paris. She became a regular model for his work. Picasso encouraged her to leave photography and take up painting again (some say after he belittled her photographic talent). She did. Friends said that she would sacrifice anything for him. According to Maar herself, I wasn’t Picasso’s mistress; he was just my master.

For Picasso, she was the woman in tears: beautiful and sad—sad, he said, because she was barren and suffered for it. Weeping Woman and Dora Maar Seated were painted by Picasso in 1937, which is the year she documented in photos the various stages of the master creating the masterpiece, Guernica. In fact, it was said that during their time together, photographing Picasso’s work became the sole domain of Maar.

Their relationship ended tragically for Dora in 1943, when Picasso took a new lover, Françoise Gilot, who was (newer, younger, better) 40 years his junior and 20 years Maar’s. The break up sent her into a tailspin of depression, ending predictably in a nervous breakdown in 1946, after her dearest friend, Nusch Eluard, wife of the poet Paul, died suddenly. Family and closest friends gone, she felt cast aside and set adrift. So, she drifted.

Eventually, Dora found a road back, as well as solace, in Roman Catholicism. She famously told author Mary Caws, After Picasso, God. So, here’s where the tightening in my chest I experienced upon first seeing Ubu re-exerts itself, but this time, because the question is so close to home: The question is, did Dora lose herself in love or was her passion for Picasso greater than her passion for her own work? Or does it matter?

In Dora’s case, it may be that fighting her way out from under Picasso’s shadow so that the fruit of her artistic talent would be her legacy rather than her talents as a muse, was just not worth the fight. Perhaps the fight was shaken out of her along with the passion. My truth is that I don’t think it matters. The work remains and Dora Maar is a woman you should know.

Dora continued to paint (eschewing Surrealism) and to write mostly meditative poetry. She died in 1997.

5 November thought to have been written in 1970[though I’d prefer the title After Picasso, God] :

Pure as a lake boredom

I hear its harmony

In the vast cold room

The nuance of light seems eternal

The soul that still yesterday wept is quiet -- it's

exile suspended

a country without art only nature

Memory magnolia pure so far off

I am blind

and made from a bit of earth

But your gaze never leaves me

And your angel keeps me.

Elizabeth Iannaci holds an MFA in Poetry, lives in Los Angeles, remembers when there really were orange groves, and shares birthdays with Red China Julie Andrews and Bonnie Parker. She has traveled extensively in Europe and Asia without getting arrested (please knock on wood), and can usually find out how to ask Where is the bathroom/water closet/ toilet/facilities? She also writes poetry and occasionally writes letters on real paper, delivered by humans.

Editor's Note:

Thanks so much to Elizabeth for sharing her wonderful writing with us and for this reconsideration of Dora Maar. You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Elizabeth Iannaci holds an MFA in Poetry, lives in Los Angeles, remembers when there really were orange groves, and shares birthdays with Red China Julie Andrews and Bonnie Parker. She has traveled extensively in Europe and Asia without getting arrested (please knock on wood), and can usually find out how to ask Where is the bathroom/water closet/ toilet/facilities? She also writes poetry and occasionally writes letters on real paper, delivered by humans.

Editor's Note:

Thanks so much to Elizabeth for sharing her wonderful writing with us and for this reconsideration of Dora Maar. You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Published on March 24, 2016 00:00

March 22, 2016

Women You Should Know - Dr. Mayme Clayton by Zoe Blaq

Women You Should Know:

Dr. Mayme Clayton

by Zoe Blaq

During my undergraduate studies at California State University Northridge, I took a Pan African studies class given by fascinating Professor Johnny Scott, who grew up in Watts and graduated from Harvard.

The day Professor Scott introduced me to Dr. Mayme Clayton, I was instantly consumed by the presence of a woman who would become my mentor, friend and inspiration. I was drawn to her passion for literature and film.

Dr. Mayme Agnew Clayton gathered one of the largest and most significant collections of black Americana in existence. She kept her collection in the garage behind her home in the West Adams district of Los Angeles, California.

We exchanged numbers after class and a week later I was volunteering in her home and had the pleasure of helping her preserve and organize books and posters in a damp and mildewed garage. I will never forget the smell of old books that permeated the air. It smelled like heaven.

We often sat and talked like old friends although we were generations apart. I was in my early twenties and she was in her seventies. I will never forget the spark in her eyes as she carefully sat her most valuable item in front of me which was the first book published by a black American in 1773 - a signed copy of Phillis Wheatley's Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. I remember the time she shared a handwritten and signed first edition of works by Zora Neale Hurston and correspondence from George Washington Carver. I was in the midst of greatness. Dr. Mayme Clayton was not only a collector, she was a visionary who dedicated her life to preserving Black history for Black people.

Mayme Agnew was born on August 14, 1923, in Van Buren, Arkansas. She graduated high school at the age of sixteen. She received a Bachelor of Art Degree from the University of California, Berkeley; a Master's Degree in Library Science from Goddard College, Vermont, and Doctorate in Humanities from Sierra University, Los Angeles.

In the late 1940's She moved to California to the West Adams bungalow where she started collecting.

By 1957, her collection grew from her work as a librarian, first at the University of Southern California and later at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she began to build an African-American collection. She started by collecting out of print books. In the 1960's, Mayme was part of the group that founded the Afro-American Studies Center Library, which is still in existence at the school today. After working 15 fifteen years at UCLA, she took a position at Universal Books in Hollywood, CaCA. When Universal Books went out of business, she managed to grab all of the books that pertained to Black society and culture – more than 4,000 volumes.

Clayton founded the Western State Research Foundation in 1972 as the world's largest privately held collection of African-American historical materials. Alex Haley, author of Roots, served as national board chairman.

Clayton was the founder of the Black American Cinema Society, which awards scholarships and hosts film festivals. In my observation, Dr. Clayton was very well respected in Hollywood, and distinguished celebrities always showed up at her events. She was a strong woman who taught me a level of focus, determination and delivery I continue to strive for. Even today, her spirit continues to encourage me to follow my dreams as a storyteller and historian. In 1999, Clayton co-founded the annual Reel Black Cowboy Film and Western Festival at the Gene Autry Museum.

Mayme Clayton and I would sit at her dining room table and have deep belly laugh conversations until we cried. We could talk for hours over the phone. Time was Seamlessseamless, age was spirit and our relatedness was bond. I went to graduate school and we lost touch with the hustle and bustle of life. Although short short-lived, our paths crossed and our three three-year meeting left a huge impact in my life.

When Clayton died in 2006, her garage held an estimated two million artifacts of African-American history. Her collection included rare books, letters, posters, photographs, newspaper clippings, and films. Her contribution to archiving will always be a valuable resource for books and documents of the Civil- War era and the Harlem Renaissance. Dr. Clayton’s library is a gem for all fFilmmakers and writers.

We draw strength and inspiration from those who came before us including those remarkable women working among us today. The dreams and accomplishments of women are part of our story. An inclusive history recognizes how important women have always been in American society and culture.

Dr. Mayme Clayton simply desired to know about her people and give children pride. She is definitely a woman we should know representing the West side. May her work continue to thrive in the altruistic heart and soul of all people.

Visit the museum in Inglewood, CA

http://www.claytonmuseum.org/

Zoe Blaq

, MA was Raised in Europe and speaks German. She is A former mental health therapist from Antioch University and also has a film degree from CSUN.

Zoe Blaq

, MA was Raised in Europe and speaks German. She is A former mental health therapist from Antioch University and also has a film degree from CSUN.Blaq is a published writer and a holistic health advocate who aims to reconnect people with their indigenous root.

Editor's Note: Wow - I'm so grateful to Zoe for introducing me to Dr. Mayme Clayton! What a wonderful woman! You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Published on March 22, 2016 00:00

March 14, 2016

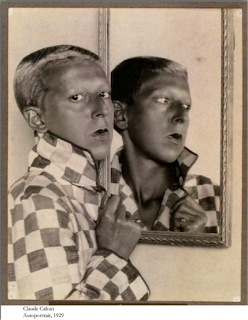

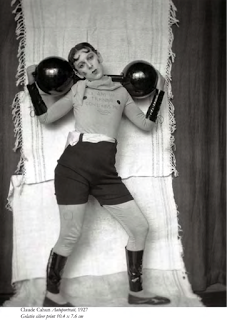

Women You Should Know - Claude Cahun by Siofra McSherry

Women You Should Know:

Claude Cahun

by Siofra McSherry

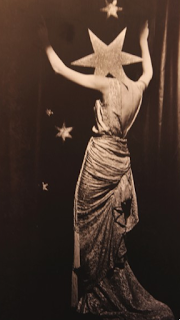

Claude Cahun (25 October 1894 – 8 December 1954) was a French artist, photographer, and writer. Born in Nantes as Lucy Schwob, she adopted a gender-neutral forename (Claude can be either male or female in French) and her uncle’s more recognisably Jewish surname. In an arrangement that echoed that of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Cahun made many of her works in collaboration with her partner and companion, Suzanne Malherbe. Malherbe likewise took a pseudonym that obscured her gender, preferring to be known as Marcel Moore; she eventually also became Cahun’s step-sister after her widowed mother married Cahun’s father. The couple lived and worked together first in Paris then the island of Jersey, where they are buried together.

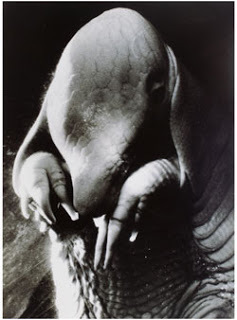

Described by Andre Breton as “one of the most curious spirits of our time”, Cahun is eternally difficult to characterise. As an artist she worked across multiple media, producing writing, photography, theatre, and performance works. She identified as a third gender that incorporated both masculine and feminine elements, and was actually described as a male artist in an early exhibition, probably due to a lack of information about her biography and self-definition. Today her best-known works are her highly-staged surrealist self-portraits and tableaux of the 20s, which play with the performance of gender and sexuality. The artist takes on characters such as Bluebeard’s wife or a fetishized weight-lifting boy, in an exploration of performative self-portraiture that prefigures the work of Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin.

These works clearly explore experimental territory similar to the photographs of Man Ray and Lee Miller, who used photographic technology to reframe, dissect, and erotically defamiliarize the female body. Techniques such as the disembodied head-in-a-bell-jar trick appear in both Miller’s and Cahun’s work: in Cahun’s version, however, the sequence is used to highlight the theatrical expressiveness of the face. Showcasing her experience on the stage, these isolated heads are absurd Beckettian characters, rather than objects or collectibles. Viewed as a whole, her body of self-portraits forms an exegesis on the performance of self, which probes the nature of the dissected identity rather than the body. Cahun’s repeated use of mirrors, reflections, and masks pay tribute to the photographic medium while providing symbolic resonance for the themes of masquerade, questioning the source and privilege of the gaze within the performative space of the portrait.

Marcel Moore and Claude Cahun settled on Jersey in 1937. During the German occupation of World War II they successfully disguised their identities as lesbians and Jews and staged an effective resistance programme, distributing pamphlets in German subverting Nazi propaganda and staging installations. They remained undiscovered for some time, since the Gestapo allegedly could not believe that two old ladies would be capable of such sustained action. Eventually detained and sentenced to death, the couple were released only when the war was over. Unhappily, much of their work was destroyed by the Nazis. Since the 1980s, however, critical interest in Cahun has sharply increased, with major retrospectives held in Paris, London, and Chicago in recent years, establishing her proper place in the history not only of surrealism but the performance of gender.

Marcel Moore and Claude Cahun settled on Jersey in 1937. During the German occupation of World War II they successfully disguised their identities as lesbians and Jews and staged an effective resistance programme, distributing pamphlets in German subverting Nazi propaganda and staging installations. They remained undiscovered for some time, since the Gestapo allegedly could not believe that two old ladies would be capable of such sustained action. Eventually detained and sentenced to death, the couple were released only when the war was over. Unhappily, much of their work was destroyed by the Nazis. Since the 1980s, however, critical interest in Cahun has sharply increased, with major retrospectives held in Paris, London, and Chicago in recent years, establishing her proper place in the history not only of surrealism but the performance of gender.

Siofra McSherry is a poet, researcher, and co-founder of the And Or new media curation project. She lives and works in Berlin.

Editor's Note:

You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know![image error]

Siofra McSherry is a poet, researcher, and co-founder of the And Or new media curation project. She lives and works in Berlin.

Editor's Note:

You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know![image error]

Published on March 14, 2016 00:00

March 8, 2016

Women You Should Know - Sherin Hegazy By Zosia Jo

Sherin Hegaz photo by Johny Smith

Sherin Hegaz photo by Johny SmithWomen You Should Know:

Sherin Hegazy

By Zosia Jo

Amidst the hustle and heat of Cairo life, a surprising artistic ecology is thriving. The independent contemporary dance and theatre scene in Egypt is unlike any I have encountered before. Forget what you thought you knew about this country, and imagine a passionate, earnest, and unexpectedly gender-equal community. Women and men in this city are creating powerful work against a backdrop of traffic, street harassment, and economic disparity. Out of diversity grows great art, and Cairo is certainly one of the most diverse places I have known.

As a female choreographer and guest here I have yet to encounter sexism within the arts sector, a statement I could sadly not make of my time working in the UK. Female artists are not as outnumbered or underpowered as recent discussions have highlighted they are in ours.

One such remarkable artist is Sherin Hegazy. She agrees it is fairly equal between women and men within the dance scene, despite considerable gender issues in the wider community, and cites attitudes to gender as the surprising cause:

“We have a problem with the cultural view of dancing. For women it’s hard [to be a dancer] and she has to fight - starting with her family. But for boys it’s the same because it’s seen as weak. Men and women fight equally.”

I first met Sherin in 2014 through friends with whom she trained in the Cairo Contemporary Dance Workshop Program. Last December I first saw her work. Sherin was one of Studio Emad Eddin’s chosen artists for their 2B Continued Festival. For Sherin, it was a chance to present a work she had already begun researching months before. After touring with Nada Sabet in a performance aimed at generating discussions about female genital mutilation in rural Egypt, Hegazy was inspired to look deeper into the experiences of women in her culture.

For her recent piece Ya Sem, she decided to focus on an issue she, and most other women here, encounter on a daily basis - street harassment. Sherin asked fifty women from all over Egypt, and from various walks of life, two questions:

If someone bothers you on the street what is your reaction? If it happened a lot over the years, did you change anything in yourself in order to deal with it?

Sherin describes changing her own clothing choices in order to stay safe, covering her arms and décolletage, even when she feels it ruins the look of her dress. She also believes many girls dress more like men, in jeans or sports clothes, in order to send a message:

“She is tough, she has no time to be beautiful; don’t attack me because we are the same.”

It was for this reason Sherin chose deliberately feminine costumes for the piece, red with flowing fabric and a flattering cut, but purposefully modest and not too revealing. She wanted to show women being beautiful and powerful at the same time.

“Since I started dancing, I dreamed of making a piece about our culture.”

Ya Sem does exactly this, in the sense that it uses Baladi Dance (known commonly as Belly Dance and a traditional dance embedded in Egyptian culture) in a contemporary way. Three dancers, Ameny Atef, Nagham Saleh and Hegazy herself, share the stage with Sabrine El-Hossamy who , usually for a woman, plays the traditional Egyptian drum- Darbuka. The piece begins with what appears to be a normal Baladi movement sequence, their faces are smiling and the mood is fun. However, the immediately comfortable audience are later confronted with powerful, unapologetic women, dancing with sticks the way men do (Tahtib), using their voices and bodies to tell the stories of those 50 women and make a clear statement- : ‘we are being harassed but we are powerful and we are fighting.’ Their performances are unified despite their diverse characteristics, ; their facial expressions change many times during the piece but their eyes never lose focus on the audience. They are telling us something important, and they won’t go quietly.

Baladi dance is a poignant medium for this work. Most Egyptians, even many men, have some experience of dancing in this style; it is the prominent social dance and even the name, Baladi, means country or local. Back in the 1950s and 60s it was enjoyed and respected. It is only in recent years that it gained a reputation as sexual or shameful. Sherin cites the wave of more extreme views on Islam coming into the country with returning migrant workers in the 1970s and 80s. During this time, many Egyptians travelled to Saudi Arabia to work and returned with different practices. Before this time the Hijab (veil) and Niqab (full black veil with face covering) were very rare in Egypt, but are now much more common.

Whilst researching the origins of Baladi dance, Hegazy also discovered something that makes her choice of movement vocabulary even more appropriate.

“In Upper Egypt girls are so shy. When a girl was forced to dance at a wedding or something she would make a movement to say NO… (Sherin moves her hip and stamps one foot) … This developed into movements with the waist, belly, butt… and it became Belly Dance.”

The response to Ya Sem was hugely positive, it won the audience vote in every category. However, sSome people told Sherin she was too direct, her meaning too clear. But it was vital that her message got across, not just to an intellectual, artistic audience, but to everyone.

“It was my goal to make something people could understand and enjoy. Something from our culture, and not just for entertainment, but to make people think.”

Perhaps the most surprising response came from a female programmer who asked her why the piece didn’t show women’s suffering.

“I was avoiding putting women suffering. I didn’t want to show this. I wanted to show women fighting.”

So often in contemporary dance we see images of angst and suffering. We make the ugly beautiful; we combine grace and skill to express truth. When you apply this to the issue of bodies, street harassment and feminism, there is a huge risk. We risk fetishizing the act of sexual oppression. I don’t need to see more images of women being raped, oppressed, silenced, and desperate. Let’s see powerful females centre stage saying ‘NO. This is not OK.’ Sherin could’ve ended up putting a pretty pink ribbon around a very dark message. Thank fully she did the opposite. She showed us the solution.

Working as a performer, choreographer and facilitator, Zosia has built a portfolio career specialising in multidisciplinary performance work including dance, spoken word and theatre. In 2010 she ran TufPoets, a monthly open mic poetry evening at the Literary cafe in Tufnell Park, London.As a choreographer, Zosia enjoys an international career including several works made in Cairo Egypt, and performances across the UK. Her solo performance work, Herstory, combines dance and spoken word and found critical acclaim at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2015. Zosia writes a blog on her own website zosiajo.com which is mainly focused on her choreographic process but also includes refelctions on dance in general.

Working as a performer, choreographer and facilitator, Zosia has built a portfolio career specialising in multidisciplinary performance work including dance, spoken word and theatre. In 2010 she ran TufPoets, a monthly open mic poetry evening at the Literary cafe in Tufnell Park, London.As a choreographer, Zosia enjoys an international career including several works made in Cairo Egypt, and performances across the UK. Her solo performance work, Herstory, combines dance and spoken word and found critical acclaim at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2015. Zosia writes a blog on her own website zosiajo.com which is mainly focused on her choreographic process but also includes refelctions on dance in general.Editor's Note: You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Published on March 08, 2016 17:00

March 2, 2016

Women You Should Know - Julie Dash by E. Amato

Women You Should Know:

Julie Dash

by E. Amato

When I was in college, I worked part-time for a woman who ran her own business. I’m not sure why, maybe she was cleaning out her book shelves, but one day, she handed me almost every book by Zora Neale Hurston. I read them all. When I cracked open Their Eyes Were Watching God, I knew I was inside something sacred, something that blended longing and fulfillment with painful precision, and something that told truths never before exposed. I didn’t know why I had never heard of it – why people weren’t shouting about it like they did Gatsby or Hemingway.

Despite the fact that I was in film school and planning to make a life in cinema, no movie had ever made feel anything like that.

Until I saw Daughters of the Dust.

Julie Dash’s out of the gate fiercely independent feature held me in its palm for 112 minutes. It is a womanist story; it is a story of peoples invisible, worlds unexplored, and humans defining the meaning of home. It is filled with indelible images and presences rather than performances. Its lines still reverberate in my head; its characters voices come to visit and stay. A film like that should have propelled Dash to the forefront of American cinema.

Instead, the next time I heard about her, she was directing and writing an episode of Showtime’s “Women: Stories of Passion,” an attempt by the cable network to both cash in on women telling women’s stories and sell some soft erotica to a late-night market. Still, it employed more than a few women directors, writers and producers during its run. Since then, Dash has had an intermittent filmography that outwardly falls short of her vision, talent, and experience.

"Everything I’ve made, pretty much, being a female filmmaker, my male teachers would say, “Why in the world are you wasting your time on that?” Illusions, Diary of an African Nun… everything was like, “Oh for god’s sakes.” That continues. When I was doing my segment of Subway Stories, I remember a lot of male crew members gritting their teeth when I had the flowers blowing across the subway track. They were looking at their watches like, you know, it’s time to go. That was the ‘90s. It continues. It’s something that female filmmakers, who were working and investigating the culture of women, faced and what we continue to face. There are different cultural set points, traditions, and all of these things that may not even interest the male counterparts and might even annoy them, because they may seem frivolous. Even with Daughters of the Dust, when we won the Best Cinematography award at Sundance in 1991, I would have people look me in the face at times and say, “Let’s not even talk about it. I don’t even know what the hell it’s about.” At that time, Matty Rich’s Straight Out of Brooklyn was at Sundance, and it won the Special Jury Prize. It was given a standing ovation. Young, urban, male films were the thing in the ‘90s."(Julie Dash, Flavorwire Interview, October 2015)

Recently, watching Beyoncé’s Formation video, I was struck by the imagery so clearly influenced by Dash’s work. It feels shameful that Dash and her creative team fashioned images so powerful they are referenced over two decades later, yet she has never been given the space to tell the visual, visceral, emotional stories she holds.

As we look closely at inclusion and at the underrepresentation of women and PoC in the entertainment industries, it is important not only to consider what – and who – we are missing, but also the lifetimes of stories we have already lost. Dash has remained a working artist, and has a new documentary, TravelNotes of a Geechee Girl, in the works. But I would have given a lot to have her skill, craft, and point of view as part of the cultural dialogue over the last 25 years. I would have liked to have her speaking to me all this time. I certainly would have traded a few of the same guys with guns movies for a few more of her human stories. To have a voice like that so marginalized out of the main, to be missing the ten or so feature films she should have been supported in making feels like a grave crime to me.

".. it’s important to do the film that you want to do — and then let people come to it. They may not get it now, but they will get it by and by. I’m not saying pop films aren’t fun, but every film is not a pop film. Every film isn’t taken from the headlines. Some films are made because they need to be made. They’re works of passion. That’s what Daughters of the Dust was." (Julie Dash, Flavorwire Interview, October 2015)

“ …unapologetic feminist, dulcet-toned poet, activist, film-maker, editor of Zestyverse ” (LossLit) E. Amato is a published poet, award-winning screenwriter, and established performer. She has three poetry collections

by Zesty Pubs: Swimming Through Amber, 5, & Will Travel, and is a content writer for The Body Is Not an Apology. She also has a special relationship with Marmite.

by Zesty Pubs: Swimming Through Amber, 5, & Will Travel, and is a content writer for The Body Is Not an Apology. She also has a special relationship with Marmite.Editor's Note: This is my favorite month of the year! I love this series, and am excited to have the inaugural post this year. You can find additional posts in the Women You Should Know series in the blog archives from March 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. If you are interested in being a guest blogger on the Zestyverse, let us know!

Published on March 02, 2016 07:14