Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 42

March 23, 2016

Holy Week Begins

Woven palm crucifixes and other objects made by indigenous people in Mexico City, Domingo de Ramos, 2015.

Palm Sunday is past; now we've begun Holy Week. I'm singing almost every day, and this responsibility, combined with the solemnity of the story that we'll hear repeated throughout the week, and its sad echoes in present-day news, have made me feel that it is not "ordinary time." Holy Week never is, but the events in Ankara, Istanbul, Brussels, and so many other places bring home the sobering fact that we humans have not learned very much in 2000 years, and are not a great deal closer to the peace and equality that was envisioned by Jesus or any of the prophets who preceded or followed him. The Powers still wield their terrible force; people who speak the truth are too often silenced by oppression, imprisonment, and death; the rich receive a different kind of justice from the poor; racism, sexism, ageism, homophobia and all other types of discrimination continue to persist; and far too many people live without proper shelter, clean water, sufficient food and, more than anything, hope for their own future.

At the same time, I'm trying to think about the advances we have made, about the hard-won but tangible freedoms now enjoyed by women, gay people, people of color: things are better for many of us than they were fifty years ago, even though there's a long way to go. The world is fitfully moving toward an end to patriarchy, and people of color will one day share power in the places where white people have exclusively dominated -- which is why we see such rage in politicians like Trump and his fearful white male counterparts in the population. Equality won't happen in my lifetime, but it will eventually come.

On Sunday, our parish put on a Passion Play in the place of the Gospel reading and sermon. Jesus was played by a young woman of androgenous appearance; she's intelligent, sensitive, and a good writer who I suspect may someday become a priest. Her performance, nearly wordless, was extraordinary. And at the end, as she mimed being dead, a wooden cross behind her, a woman in a shawl came up the aisle singing a lament, just keening, without words, in a strong voice that seemed to perhaps Greek - the choreographer/ director told me she had heard her at a funeral last year and approached her to be Mary Magdalene in our play. I was moved by her voice: so unexpected, and so universal and timeless in its sorrow.

Last night, in a dark church, we sang Compline. It began with the Beatitudes, part of Jesus' Sermon on the Mount:

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn: for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek: for they will inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness: for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful: for they will be shown mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart: for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers: for they will be called children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

It's odd. I don't believe a lot of what is in the Bible, and I certainly don't take it literally. I deplore a lot of what the Church has become and what it has condoned throughout history, while recognizing its capacity to be a force for good. But the core message of Jesus' teachings, contained in the Gospels, is simple, and I've tried in my life to listen to it, and to follow it. Holy Week is a time when I come face-to-face with my own shortcomings: my own denials, my own ways of deserting the truth and running away from Loving my Neighbor, with a capital L. The blueprint is all right there in the Beatitudes: humility, compassion for those who mourn, simplicity, working for justice, showing mercy, trying to become more pure of heart, working toward peace, and having courage to do the work of seeking justice and righteousness. There is nothing here about violence as a means to an end, nothing about retribution, nothing about superiority or "winning." How totally unsatisfying! And yet, it's only by loving one another in spite of all our differences that a just and peaceful world will ever exist.

I'm glad that my life includes Lent as a time of reflection, and Holy Week as a time to really go deeply into these thoughts. It's often uncomfortable for me, but when we emerge on the other side -- hopefully into spring as a symbol of new life -- I usually feel that I've learned something. And it helps to sing my way there, too.

March 19, 2016

Birthday Bouquet

This is the thirteenth birthday of The Cassandra Pages, and what better way to celebrate than with some spring flowers (especially when the reality outside the window is snow on the ground, and 4 degrees Celsius.)

This blog began during a grim time, as George Bush Jr. insisted that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, and the nation geared up for war. 2016 feels grim, too, with Trump poised to clinch the Republican nomination, and the only progressive candidate, Bernie Sanders, increasingly unlikely to become the Democratic nominee. Everyone is affected by American politics, and Canadians are watching this election with stunned dismay. I'm glad we moved to Canada, but of course we will vote in the American election: as citizens of both countries, we are able to have two passports, vote in both places, and required to file taxes to both countries.

I can tell you that it feels good, however, to pay most of those taxes to a province and country whose values are largely very similar to Sanders' -- the fight for progressive policies for the benefit of the common people and a sustainable future must continue, no matter where we are.

Looking back, I realize that this blog has been an important way for me to deal with the vicissitudes of these years, and I've tried to make it both a calm, steady place for myself and the readers, where we can concentrate for at least a short time on the things that make life meaningful and often beautiful, not glossing over difficulties, but at least trying to keep them in perspective. I've been immensely grateful for the companionship I've found here, as well as your encouragement about the various endeavors that have been described or illustrated.

Thank you, and onward!

(and thank you to our friends G and M, who brought us this pot of narcissus last weekend - I've enjoyed watching them bloom this week so much!)

March 17, 2016

Alarm

Someone came into the bathroom while I was in the stall. I heard running water, and then a hand banging on the paper towel dispenser, but it must have been empty because a male voice said: shit. The door opened and shut. I went out of the stall and saw the sink and floor covered with blood. I was getting towels from the cabinet beneath the sink when the door opened again and a young man came in, a rag in one hand, the other holding a towel to his chin. Let me help you, I said, wiping the basin, careful not to get blood on my hands. What happened, did you cut yourself? No, he shook his head, I just fell. Your chin, does it need stitches? I don't know, I haven't looked yet, and he pulled his hand away so that I could see, tipping his head up toward me like a child. I don't think so, I said. He sank down to his knees on the tiles then, faint or just stunned, I wasn't sure. I kept cleaning, one eye on him, and then he got up and we left together and he went to his own studio where his friends stood, waiting.

March 12, 2016

Stitching my way toward spring

I like to think that my great-grandmother's thimble made her finger as sweaty as it does mine. I like to think about the quilts she and my grandmother made together, and sometimes I sleep beneath them. We were all named Elizabeth... Not long before she died, in 1992 at age 92, my grandmother asked me, "You have Libby's thimble, don't you?"

"Yes," I said, "would you like it back now?"

"No," she said, sitting back in her chair, satisfied. "I just wanted to make sure where it was."

Each stitch is a tiny step closer to clarity, to restoration, to the spring that is inching its way north. Across the city, a friend writes that she's just bought a balloon for a friend in hospital. The morning's snow flurries have given way to bright skies, and the afternoon sun butters the walls of the carpentry school, where students brush off sawdust and look forward to the weekend, a few beers, some music with friends. I'll see an old dear friend tomorrow, and sing a mass by Delibes on Sunday. Another line of stitches, another pocket to hold our warmth next winter. Such inconsistency in these stitches, these steps! I've been doing this my whole life and I'm still a beginner.

March 8, 2016

"How do I really want to be?"

Those words, written by Pema Chodrun, have been echoing in my head since writing the last post. Taking a few steps back, I've realized that several factors have been affecting my mood: the negativity and despair surrounding the American election; the long slog here through the end of winter; lingering illness; disappointment and some worry about things that happened during our trip to Mexico. All of that has contributed to difficulty getting back on track with positive forward momentum. This is the hardest time of year for me, as it is for many people living in the north, and my journal confirms that it's usually that way for me. I just have to get through it. On top of that, it's the penitential season of Lent, and we've got a couple more weeks to go, plus the grimness of the Holy Week singing marathon, before things start to lighten up. Unlike the Mexican church below, our Anglican cathedral doesn't allow flowers during Lent, let alone red ones!

But as I thought about all of this, and about my role as an artist, and heard from some friends both in comments and in emails, Pema's words began to resound: "How do I really want to be?" She was talking about facing difficulties, too, and particularly about the loneliness of spiritual leadership (in her case); all of us face different kinds of existential loneliness. She wrote that she posed this question to herself, "and then I began to settle down." I understood. For me, it's the key question, unlocking the door I had temporarily forgotten.

So the first thing I've done is to get back on my meditation cushion, back on the piano bench, and back to some quiet, repetitive work: hand-quilting the pieced top that I began many months ago.

At the same time, I've been thinking about art and writing in the context of Pema's words, and also in the words of my friend Natalie d'Arbeloff, who wrote that while many artists are able to do powerful images of protest, or showing the tragedies and gruesome side of our world, "that is not my path." And it's not mine, either. While I appreciate the sculpture by muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, below, his often-tortured vision of the world doesn't move me - it disturbs me and assaults me. It's too much.

"How do I want to be?" is another way of asking "Who do I want to be?" and the answer to that is that I want to be a person who sees, and helps other people see, the beauty and love that exist in the world in spite of everything.

I am having trouble with a kind of focus on beauty, prettiness, gentility, and pastoral niceness that feels like the artist's head is in the sand. You don't find this in societies where there is a lot of poverty, violence and oppression, except among the ruling classes: the people who because of social standing and privilege are able to live apart from other people's suffering and difficulties. What you do find, outside the ruling classes, is often exuberance, color, and a deliberate embrace of what is beautiful in life: human relationships, simplicity, animals, food, children, natural vegetation, "place" in relation to people, play, warmth. I remember being told by a priest who had spent a long time working with Oscar Romero in El Salvador that, to his surprise, he had learned the most about joy from people who had endured the most suffering. I've spent enough time in Mexico now to believe that this is absolutely true.

This reflecting I've been doing has not shown me a clear path yet, but it's showing me what I don't want to do, and have never wanted to do: I don't want to be the naysayer, the bearer of terrible news, the person who dwells on the negative and beats people over the head with guilt, whether it's about the environment or politics or oppression or war. For articulate people to speak out is important; and helping financially, personally, and through our talents and skills is essential for all of us who can -- but the negative is not where I want to focus my entire creative energy. Yes, our eyes become clouded by what we see and it affects us, sometimes a great deal, to the point where we get stuck and can descend into depression and inactivity. But when I look at our extraordinary world, and at most of my fellow human beings, what I feel is love: in spite of everything. And love is always meant to be transformative.

So the work is actually not work at all: it's stepping away from the noise, getting one's head out of the way, and allowing that transformation to happen, whether for the first time or the thousandth. We all have our own ways of getting back on center, of taking care of ourselves, starting with the simple awareness of our breath and the miraculous fact that we are here, in this present moment. Going back to basics isn't a failure, it's essential -- and in my case, that's exactly where I'm headed.

March 4, 2016

Out into the Desert

All work shown in this post is by Mexican sculptor Javier Marin.

I've been thinking a lot, since Mexico but also before, about what makes people create the art they do. In my feed reader, on Flickr, and on Instagram, I "follow" a number of highly skilled and talented artists, and I've noticed that their work tends to fall into groups. On the one hand, there are the Mexican and American leftist printmakers, mostly young, often male, radical, political, influenced or participating in street art and body imagery, often obsessed by death symbolism, fantasy, and hyper-realistic animals.

And then there are a number of artists, mostly British, who do contemporary landscapes and still-lives in various media, depicting a pastoral and interior world of beauty, inhabited by sleek hares and whippets, songbirds, figurines and dishes, flowers and seedpods. Their work, especially in printmaking, is extraordinarily fine -- and yet it could not be more removed from the gritty urban vision of the Mexicans; it belongs to a world where people can think about decoration and beauty in relative comfort. There's an immediate affinity because of my own heritage, but...it's both me and not me. Or perhaps it was once me, but no longer.

While in Mexico, I was blown away by the work of a contemporary sculptor, Javier Marín. Marín does large-scale figurative pieces in bronze, wood, and resin, and he is one of the best sculptors I've ever seen.

At first, the work looks classical: it's the human body, it's beautiful, it's realistic, and the poses and style (whether in the round or bas-relief) definitely reference the Greeks. Marín doesn't deny the connection, but says he feels an even greater affinity to the 16th century movement of Mannerism, and artists such as Pontormo, who subverted the ideal proportions and elegance of classicism through compositional tension and instability, and an intellectual approach to the subjects.

Marín's impact and message are therefore absolutely current: the proportions are altered; his figures, heads, and bodies are slashed and marked; they have been sawn apart and put back together with wire reminiscent of barbed wire of concentration camps; and their attitude of nobility and suffering forces our gaze inward and outward at the same time, toward our humanity and our inhumanity alike.

Marín's work was exhibited both in large public spaces and intimate rooms, and these spaces become part of the conversation the artist initiates: who are we, in relationship to the grand plaza, the governmental edifices, the cathedral and the history it represents?

Or in this chapel with its huge old-master paintings of the Holy Family, what is this monumental wooden figure, titled Mujer? This roughly-chiseled every-woman, but only from the waist down, her crude bare toes reminding me of the lines in Luisa A. Igloria's poem, Dolorosa, "her unshod peasant's feet/bloated with edema."

What is this white cascade of bodies and body parts, this waterfall that forces me to think of holocausts, mass graves, unsolved "disappearances," drone victims, and drowned refugees of our unhappy history and current miserable world?

And next to it, this gilded woman ascending; at last, perhaps, free?

Much has been written about Marín, in Mexico, but he's relatively unknown outside the country; I find this incredible - but then, he's Mexican. Thankfully, he's still young - in his early 50s - and that could change.

The common denominator in all of this work is the high level of skill and dedication of the artists: they are all working hard, doing their best; they're just coming from such different places. And of course there are also outliers: artists from the UK whose work is grounded in these same traditions but who address more thorny subjects - Clive Hicks-Jenkins is one; Mexican artists whose work is less political, and achingly beautiful, responding to the people and the land. Even Diego Rivera, whose murals were filled with political protest, painted many paintings of this type.

And so I find myself reflecting on where I fit, and where I want to go with my own creative work. I draw, every day if I can, and in recent years the drawings have often used objects from my daily life, but I'm more and more uncomfortable with the purely decorative, with the pure search for beauty, harmony, order, which no longer feels complete or consonant with my emotions, thoughts, or values. I realize that my drawings are often a way of keeping despair about the world at bay, of doing something in a given day that is creative and life-affirming - but I feel the drawings are more honest when they contain some reminder of mortality, loss, grief, sorrow, even cruelty: a skull, a fossil, a bone, a wilted plant, dead things - or else reflect the juxtaposition (or collision) of cultures which is the place I seem to inhabit more and more. The landscape, to which I've always felt such an affinity, is a symbol for me of both desolation and comfort, of human isolation and strength. And the medium of relief printmaking seems to offer opportunities for figurative work and bolder, more graphic statements about the human condition. Conversely, as the work of these other artists repeatedly show, technique and good ideas have to work hand in hand - both are crucial, but neither sufficient on its own - and both must continually evolve.

I think we need to think hard about what we're doing as artists and writers, musicians and performers, and to be aware that over our lifetimes we need to grow and change and keep moving deeper. The themes and subjects that draw us can be a pointer toward our core self, but repetition itself is a kind of death into which we can be lulled by comfort and ease, or, equally, seduced into by praise. I don't know exactly where I'm headed, and I'm aware that the path is a rocky upward one, but I've come to trust it. In the end it's not even the art that's important, but the progress of the spirit. I'm grateful for the chances to travel and experience and be curious, but in today's interconnected world we don't actually have to leave home to push ourselves out into a wider wilderness, we just have to be willing to look, think, and learn from our discomfort, restlessness and yearning.

Related articles

At the Jumex

At the Jumex Coyoacan (2) y La Casa Azul

Coyoacan (2) y La Casa Azul

It's Not Just About the Food

Over at jonzphoto.com, Jonathan has written and illustrated an excellent post about ethnic diversity, Vermont, Montreal, and some of the other-culture friendships that have changed and enriched our life.

March 2, 2016

Sketching in Mexico

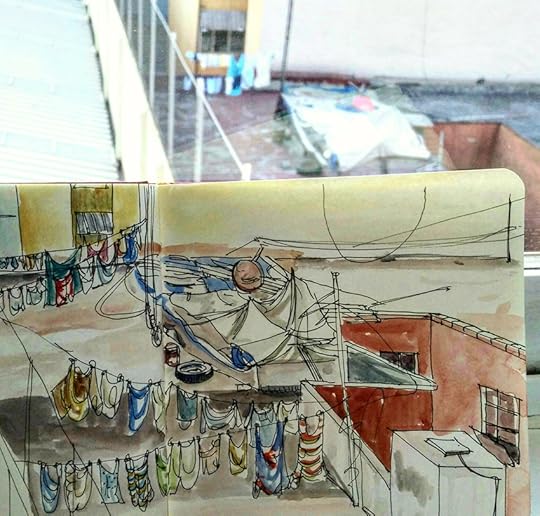

Laundry on the rooftops, the day before we left.

Several people asked me if I planned to do some sketching on our trip, and the answer was yes. Here's some of the evidence. I would have liked to do more, but it's hard when you're always on the move and not wanting to devote an hour or two of sitting-down-time to making a drawing. Still, I'm glad that I was able to do these, because a sketch somehow becomes a special kind of memory more than a photograph, probably because you remember where you were, how you felt, and what was happening as you concentrated on the sketch. During the hours when I was sick and had to stay in the hotel room, I turned to the sketchbook and was glad for that distraction, too.

The first sketch I did (above) was from the steps of a large gazebo in the Alameda Central, looking across Hidalgo at the very old churches there, Templo de San Juan de Dios and Parrochia de la Santa Veracruz. At the bottom you can see the tarps and umbrellas of the vendors who set up along the street every weekend, selling everything from books to bobby pins to candy and cast-off clothing. The tilt you see in the tower at right is real, a result of age and earthquakes. In fact, a few days later I was inside that church, and accidentally stepped up to my ankles in water that was seeping into the structure. In a few hours there were emergency crews standing outside, trying to figure out what to do, and the church was closed for the remainder of our visit. It's hard to imagine the expense or responsibility of maintaining these historical structures in a place that is subject to frequent earthquakes.

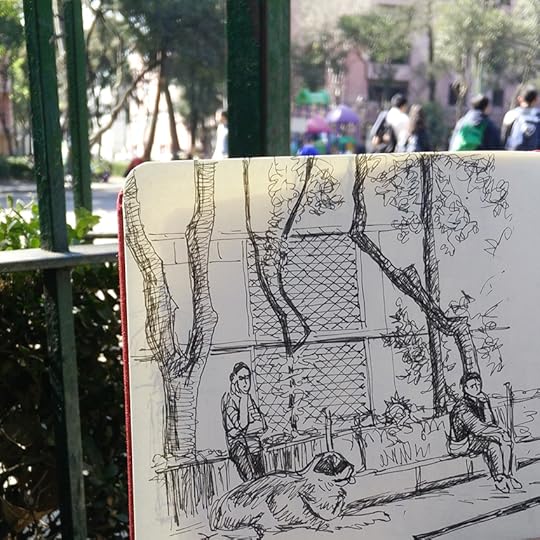

This is Parque Rio de Janeiro in the Condesa district. The crossing signs on the streets of the Condesa show a person wearing a hat and leading a dog on a leash - a Mexican friend told us that's because everyone in that upscale district wears a hat and has a dog. When we visited the park it certainly seemed to be true, and I had to record this large St. Bernard and its bored, cell-phone obsessed owner for posterity.

A bouquet of orange roses graced our room for nearly two weeks. After being able to buy beautiful flowers of all kinds for next-to-nothing, it's painful to come back to Montreal where they cost a small fortune: a bunch of tulips was a whopping $12.99 at the supermarket yesterday. I didn't buy any, but this is when we really need them!

Dinner in our room one night: a baguette (yes! and it was good!) with prosciutto, tomato and avocado salad, some Manchego cheese, and grapefruit sections with lime. (Oh, and a little tequila.)

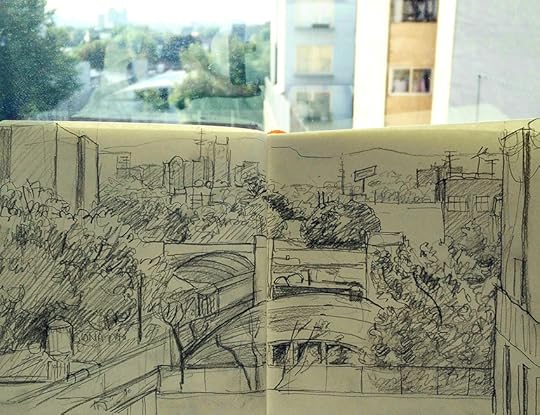

The gloriously ornate Metropolitan Cathedral, from a perch overlooking the Zocalo.

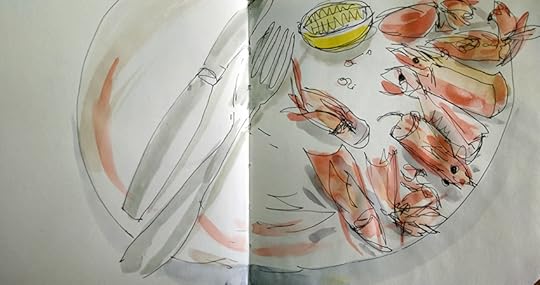

Shrimp shells, after a very good fish/seafood dinner in Colonia Roma.

The hotel bathroom (getting a little desperate here!)

And the view from our hotel room window, looking toward Tacubaya over the rooftops.

February 25, 2016

Form

Sculpture by Jimenez Deredia

In Mexico I am always, immediately struck by the emphasis on form in all the arts. Whether dealing with architecture and public spaces, with fresco painting, or - especially - with sculpture, the emphatic and confident use of form is a major, defining aspect.

If we look around, there are reasons. The land, shaped by volcanic activity, is dramatic, and these shapes were echoed in the iconic stepped pyramids of Teotihuacan and Tenochtitlan.

The plants are sculptural.

The people themselves are monumental and beautiful.

There is a long history of form-emphatic art, from the very early Olmec heads (around 1000 BC)...

...through the long pre-Columbian period of remarkable ceramic sculpture...

...combined later with the Spanish wood-carving tradition.

Form finds expression in literal, representational ways, but also in abstraction: Mexico has a strong tradition of graphic design, surface decoration, typography, and pattern.

I'm always fascinated to see contemporary expressions of these traditions. While at the Museo Franz Mayer for the Decorative Arts, we saw an exhibition of contemporary ceramics. It was in two parts: a biennial competition for functional ceramics, and a separate room containing (mostly large) works by master living ceramic artists. I was crazy about some of these latter pieces and took pictures to show you:

Cactus, by Javier Villegas

Bodegon con taza y peces, by the same artist.

Florero, by Marta Ovalle

Horizontes continuos, by Gloria Carrasco. Each of these pieces is about two feet in the widest dimension. Aren't they beautiful?

February 23, 2016

The Air We Breathe

A clear day, two years ago.

Mexico City's air quality has improved in the last two decades, but it is not exactly good. On clear days, the view from our hotel room included the mountains in the distance, but during this particular stay, that was an exception.

A typical recent day.

The city is at 7,000 feet, and fills the Valley of Mexico: once surely one of the most beautiful places on earth, surrounded by mountains including active volcanoes more than 17,000 feet tall.

Above, The Valley of Mexico from Del Rey Mill, by Jose Maria Velasco, painted in 1900. The Chapultepec castle is in the middle and the city itself is the small white expanse in front of the lake. Today the castle and its woods are a park, with the city extended all around them, over all the green space you can see in the picture above. Popocatepetl, on the right, erupted recently and has no snow cover at the present time.

Looking in the same direction on a pretty clear day, from the Torre Latinoamericana: nothing but city fills the entire valley.

--

For the first couple of days, travelers from lower altitudes, like us, generally experience some breathlessness, especially when walking fast, carrying luggage, climbing stairs. I don't usually have too much of a problem with that. But I was very aware of discomfort in my lungs, and found myself coughing. After a week, I came down with a respiratory flu. Whether it's something I picked up on the airplane, or in the crowded metro, I'll never know, but I'm convinced that my lungs were already struggling from the pollution. Now at home, a week later, I'm still ill but gradually getting better. Yesterday when I looked out of the airplane at the frozen fields of Quebec, I wasn't shuddering like many of my fellow passengers: I couldn't wait to take a breath of that cold, clean air.

I was on the street every day, both as a cyclist and pedestrian. Every day, trucks passed us belching black smoke, buses filled the air with diesel fumes, the highways were choked with car traffic. In our neighborhood and all through the city, many people work outside or in spaces that are open to the outdoors - there's no way they can avoid exposure to the air. The effects on everyday health must be devastating. I don't think I couldn't survive there, but for the 22 million citizens of Mexico City, there's no choice. What about all the people who live in the Maximum Cities of the world, and can't fly away to places with better air, let alone water and sanitation? I have a close friend in Beijing. She has no options in that very polluted city.

What I observed, and the fact of my own fragility, have made me think a lot this week about us as biological organisms, with simple needs for air, water, and nutrition: things the earth naturally provides in abundance. Most of the time, we don't even think of ourselves in this way - like a plant or a bird or a goldfish - so dependent are we on our technologies and the ways they keep us removed from and oblivious to the cycles of life. I've thought about what we are doing to ourselves and all the living things, and it's been more appalling to me than ever. Air to breathe: the most basic requirement of all, and yet for millions and millions of human beings, even this is impossible.

What do the indigenous people think? First the Spanish came and violently took away their land, massacred thousands of people, decimated their rich and highly-developed native culture, and converted the people to Christianity; then industrialization destroyed much of the natural world with which they had always lived in harmony. And now, many of the indigenous people are forced to come into the city for work, to sell their foods or handcrafts on the street, or worse yet, to beg. In Mexico as nearly everywhere, the darker one's skin, the more discrimination there is, the more menial the jobs, and the fewer chances for education and economic advancement. There's more than one way to suffocate, and unfortunately the people with the least power are always the ones who suffer the most.

As I hope is obvious, I love Mexico, and I don't mean to be negative - simply realistic about some of the very real problems that became even more obvious to me during this trip. The legacy of colonialism continues, and we have to look it in the face if there is ever to be a hope of addressing what we've wrought.