Lee Martin's Blog, page 60

April 13, 2014

The Objects of a Character’s World

I’m reading Carrie Brown’s wonderful novel, The Last First Day, which I somehow missed when it came out in 2013. It’s the story of an aging couple and their sweep of time. The book opens on the first day of the new autumn term of New England’s Derry School for boys, where the husband, Peter, is the headmaster. The wife, Ruth, is getting ready to attend the opening assembly and to host a reception for the faculty that evening. The opening pages come to us from deep within Ruth’s consciousness as she readies herself for the evening’s events and as she contemplates the rough spots and the compromises of her long marriage. So little is happening as far as plot events, but so much is taking place inside Ruth’s heart, mind, and soul.

But still there’s narrative motion, just enough of Ruth moving about the house, making preparations, to let us feel that we’re heading toward something significant. There’s also enough of an unsettled feeling—the ominous threat of a storm, the loneliness of Ruth’s duties, Peter’s impending retirement and what that will mean to the balance of their lives—to keep us very interested in what will happen. The writing is beautiful; the narrative is graceful and leisurely; the details are precise and not just there for set dressing.

Consider the moment when Ruth, feeling that time is growing short, and she really must be leaving for the assembly, goes into the bathroom and takes notice of the items near the sink:

She went into the bathroom. In the mirror over the sink, the late afternoon’s light slanting through the window struck one side of her face—chin, high cheekbone, temple—brightening the silver of her hair. Two toothbrushes in an enamel mug on the sink’s edge, a cracked oval of pale green soap in a scallop shell, a damp washcloth draped on the glinting tap. . .these, too, were illuminated.

How beautiful such ordinary objects appeared, she thought, like the humble objects in Vermeer’s paintings—table, ewer, drape of fabric—mysteriously elevated to the level of sacrament.

Those details: toothbrushes, mug, soap, washcloth. Where else but in our bathrooms are our lives revealed so intimately? Because we’ve lived with Ruth so long and so well in the first thirty-eight pages of this novel, these details stand out for us as they do for her. A description of them earlier wouldn’t do the same sort of work because we wouldn’t have yet known what it feels like for Ruth to move through her life on this particular day. When we encounter them on page 39, though, we know enough about Ruth and Peter that these details are alive with this marriage.

So here’s a writing activity that we might use to start a new piece or to take us further in our thinking about something already in progress.

1. If starting a new piece, imagine a character’s bathroom (this can work as well for nonfiction as it does for fiction) and take note of three very specific items. Be precise. If working with a piece already in progress, have a character walk into his or her bathroom and take note of three specific items.

2. Give your character something very specific that has happened in the last twenty-four hours. Maybe a child has left home. Maybe a letter has come in the mail. Maybe a love has been lost. Maybe a great joy has come.

3. Give your character a fear for the future.

4. Give your character somewhere to go and someone to meet there immediately after leaving the bathroom.

5. Don’t let your character touch any of the three items in the bathroom. Write the moment just before the person walks into the bathroom and sees them. Don’t let the character touch them. Make them be expressive of the character’s state of mind.

I hope this exercise will open up aspects of material that might otherwise remain closed. The objects of our worlds can mean so much if we take the time to know the inner life of those who own them.

April 7, 2014

Genre Jumping: Writing Both Nonfiction and Fiction

I write both fiction and nonfiction, and with the latter I have an admitted preference for narrative. No matter the genre, then, I see myself as a storyteller. I like to tell stories, and sometimes I like to tell them about invented characters, and sometimes I like to tell them about real people.

When I have material that I believe is important to announce and claim as my own—and that’s usually because there’s something I need to explore about myself and my experience, something I need to investigate that only the particulars of my own world will make possible—I turn to nonfiction.

Most of the stories in my first book, The Least You Need to Know, were about fathers and sons in difficult relationships, and those stories were satisfying to me for what I was able to do with structure, character, and dramatic irony. The intersection of imagination and experience allowed me to do with my real-life material what I wouldn’t have been able to do in nonfiction. I was able to stylize the material in a way that, because I was free from the strictures of what really happened, deepened character, complicated situation, and more aesthetically shaped the dramatic potential that first brought me to the page. Working from autobiography to fiction also allowed me to trick myself into writing about personal experience. Because I was free to hide behind the scrim of invented characters and situations, no matter how closely aligned with myself and my history, I was also more willing to come to dramatic truths that were important to the stories and also important to me.

But I’m not sure that I was aware of the latter while I was writing these stories. Fiction brings me to truths that are personally relevant, but it doesn’t bring me to the same sort of truths that my work in nonfiction does. In that genre—and my work there began with my second book, my memoir, From Our House—I’m hoping for a different truth from the narratives. In that book, which directly took on the autobiographical material that had informed so much of my fiction, I was still interested in structure, character, and dramatic irony, but because I was dealing with factual material I couldn’t freely arrange episodes, create dimensions of characters that didn’t exist in the real people about whom I was writing, or engineer ironies that never occurred. I could still shape, but I couldn’t invent. Imagination was less at play, but I could still use the tools of fiction to claim my own experience, to face it directly, and, in shaping it, to question, to explore, and finally to discover truths that were personally significant.

Perhaps there’s an honesty and integrity in this kind of work that holds the writer close to the bone. Perhaps aesthetic restraints open the writer more to the act of discovery, though I believe that when the fiction writer is working to the best of his or her ability, the same thing happens. To dissolve some of the boundaries between the two genres, I recently came up with a writing activity that encourages lying in nonfiction:

Open a piece of cnf by telling a lie about yourself. Don’t stop to think. Just go with the first thing that comes to you. Be as outrageous as you’d like.

2. Admit the lie, using this prompt: “That’s not true at all. The truth is. . .”

3. Embrace the lie, using this prompt: “Oh, but how I wish it were true, for if it were. . .”

4. Let the lie bring material to the surface that you might be hesitant to explore otherwise by using this prompt: “Why would I spin a lie like that? When I think of that lie, I also think of. . .”

The objective is to let fiction provide a doorway into truths about your life that you might not otherwise notice. A blend of fiction and nonfiction can sometimes open our material to us in profound ways.

March 31, 2014

Ten Thoughts on the Writing Life

More and more these days, I’m convinced that how we approach our work has a crucial connection to the quantity and quality of the work we produce. Much of our writing lives are spent in solitude, both physically and mentally. We often hope for good results so desperately that we rush the process. Sometimes we’re too afraid of failure and too afraid to occupy the uncomfortable places where our writing takes us. We have to respect the fact that we’re imperfect and may fall short of what we imagine for a particular piece, but we also have to be courageous enough to keep doing the work, trusting in our talents. Sometimes we’ll succeed, and we’ll be tempted to believe that now we’ve made it and from here on everything will be smooth sailing. It won’t be. We need to accept that. Each blank page or screen—each new piece—carries with it its own set of challenges to meet. When we fall short, we’ll be tempted to fall into despair. We have to resist that temptation. We have to keep going steadily about our work. Being regular with our writing routines is a good thing. Writing is a self-generating process. The more we do it, the better we do it. This means we sometimes have to remove ourselves from our loved ones. We have to close the door to our writing rooms and have that period of uninterrupted time to work. We should never forget, though, to get out of those writing rooms to explore the world. We have to experience life before we can shape it. Success will come, no matter how slowly or intermittently. Writing is a lifelong apprenticeship, full of peaks and valleys. Take time to celebrate the peaks; don’t dwell too long in the valleys. Take pleasure in the work.

1. We have to be comfortable with solitude.

2. We have to exercise patience.

3. We have to be fearless.

4. We have to be afraid.

5. We have to resist making too much of our successes.

6. We have to resist making too much of our shortcomings.

7. We have to put in the time and the effort.

8. We sometimes have to be selfish with our time even if we end up disappointing those who matter most to us.

9. We have to open ourselves to the world and all its mysteries, and contradictions, and wonders.

10. We have to take time to celebrate our successes, but not too much time; we have to get back to work.

March 24, 2014

Rest

Please forgive my absence this week. Sometimes, as Wordsworth wrote, “The world is too much with us; late and soon.” I hope to return next week. Until then, let this passage from Maya Angelou’s Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now be enough:

“Every person needs to take one day away. A day in which one consciously separates the past from the future. Jobs, family, employers, and friends can exist one day without any one of us, and if our egos permit us to confess, they could exist eternally in our absence. Each person deserves a day away in which no problems are confronted, no solutions searched for. Each of us needs to withdraw from the cares which will not withdraw from us.”

Peace to all of you: past, present, future.

March 17, 2014

Trouble? I’ve Seen Trouble

I recently posted a quote from E.B. White on my Facebook group page, a quote that spoke to me about the importance of trouble when it comes to generating a plot: “There’s no limit to how complicated things can get, on account of one thing always leading to another.”

I’ve always agreed with those who say that creating a plot is a simple matter of getting a character into trouble and then seeing what he or she will do to try to get out of it. With that in mind, I’d like to offer up a few ways to get your characters into trouble.

1. Sometimes trouble pays a visit. In Raymond Carver’s “A Small, Good Thing,” a young boy, Scotty, gets hit by a car, and though he appears to be unhurt at first, he later slips into a coma, and then dies. His mother forgets about the cake that she ordered for his birthday from a baker who was abrupt with her. When the baker starts calling the house to say the cake hasn’t been picked up—saying things like, “Have you forgotten about Scotty?”—the trouble that started the story takes on an added dimension. No longer is it merely bad fortune striking. It’s now something that requires a response, and that response is the eventual confrontation with the baker, which leads to a surprising moment of grace. The combination of bad luck and the presence of the baker lead us into the complicated terrain of suffering and compassion. If trouble puts pressure on a character, increase the pressure from a source outside the realm of the trouble. Press harder until your character has to act.

2. Sometimes we make our own trouble by what we decide to do. Sammy, the teenaged narrator of John Updike’s “A & P,” quits his job as a grocery clerk cashier in support of the girls who have violated decorum and come into the store in their bathing suits. Of course, his gesture goes unnoticed by the girls, and Sammy ends up with a consequence he couldn’t have predicted: “. . .my stomach fell as I felt how hard the world was going to be to me hereafter.” Use dramatic irony to complicate the trouble-causing action. Let the character’s intention produce its opposite result.

3. Sometimes we make our trouble by letting people believe something is true when it isn’t. The central action of Ian McEwan’s novel, Atonement, depends on thirteen-year-old Briony Tallis, who makes a false accusation based upon facts she believes to be true. Her accusation changes lives forever. There are variations of this plot-making strategy. Perhaps the character tells the truth about something heard or seen, but leaves out other facts in order to let the listener construct the narrative that the speaker desires, a narrative that the speaker knows to be a partial truth. Sometimes a character says or does something only to have it misinterpreted. The key here is to arrange the facts in such a way, with whatever back story is necessary, so more than one narrative is plausible.

4. Sometimes we make our trouble by trying to run away from what we’ve done, or by being afraid of what we might do. The mathematics tutor, Henry Dees, in my novel, The Bright Forever, gives his pupil, Katie Mackey, a fatherly kiss on the cheek, but because he knows people already consider him an odd bird, he knows that if anyone were to have witnessed the kiss, they would consider him suspect. Adding to his fear is the fact that he’s already started to question his own motivations. His fear leads him to a moment of paralysis at the time when he most needs to act, thereby creating a trouble that will haunt him the rest of his life. An entire plot can be spun from a character’s questioning of his or her own action.

I’m particularly interested in how people create their own troubles, either from the git-go, or from how they respond to misfortunes that befall them. As the quote from E.B. White indicates, things will always get complicated if we let one thing follow another. If we can add a little pressure, irony, misinterpretation, or multi-layered motivations, we can help those complications along. Too much restraint or politeness ruins a good narrative. Put your characters into action. Let them run at cross purposes with others, with dramatic situations, and with themselves, and you’ll create a memorable chain of events. We have to make room for the human flaws that can lead to trouble. Then we have to make enough room for our characters’ attempts to save themselves. One thing leads to another. It’s a good thing for a narrative to remember.

March 10, 2014

A Sunday Meditation

Writing well isn’t only a matter of technique; it’s also dependent on what we allow ourselves to feel. Often, my strongest feelings come from childhood. Driving back today from Indianapolis, I came upon a radio station that was playing old-time church hymns: “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder,” “In the Sweet By and By,” “Bringing in the Sheaves.”

Writing well isn’t only a matter of technique; it’s also dependent on what we allow ourselves to feel. Often, my strongest feelings come from childhood. Driving back today from Indianapolis, I came upon a radio station that was playing old-time church hymns: “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder,” “In the Sweet By and By,” “Bringing in the Sheaves.”

Sometimes I wake on Sunday mornings with the feeling that there’s somewhere I’m supposed to be. I call back the memory of the churches of my childhood: the hard wooden pews, the dusty smell of the hymnals, the thimble-sized communion cups half-full of Welch’s grape juice, the Saltine cracker from which the believers broke a piece of the body of Christ, the red-edged pages of New Testaments, the preacher extending the invitation to salvation— Jesus is waiting. Won’t you come to him now?

I was fifteen when I accepted the call, and I still remember the feeling that filled me after my baptism, this feeling of life starting again, of all my wrong steps being cleansed, of every sin forgiven. This was love, my mother told me. This was Christ’s love. Although I eventually dropped away from the fold, and remain outside it even today, I never forgot that lesson. I never forgot that when you truly and wholly love someone, you forgive them for falling short, forgive them the injuries they bring you, forgive them for being less than what you want them to be. All the while I basked in the warm comfort of this new life after my baptism, I began to see how my mother’s faith—her refusal to stop loving my father no matter the ugliness of his temper—might just be enough to save us.

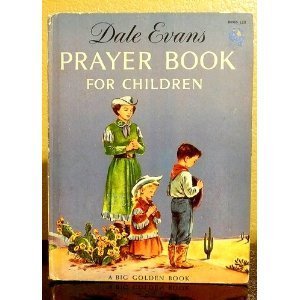

Listening to those hymns today, I remembered how my mother used to read to me from A Big Golden Book, Dale Evans Prayer Book for Children. Dale Evans, “Queen of the West,” the wife of Roy Rogers, the square-dealing, “King of the Cowboys.” They stood for all things decent and right, and as hokey as that may seem these days, I still look back at the boy I was and my mother’s attempts to keep reminding me of everything that was good in the world, with great affection. She was no Dale Evans, mind you. She couldn’t do rope tricks, couldn’t ride, couldn’t sing worth a lick. But she was a mother who wanted her son to know he was loved. From this book, I learned my first prayer of gratitude: “God is great and God is good/And we thank him for our food.” And I learned how to ask God to take care of me: “Now I lay me down to sleep/I pray the Lord my soul to keep.” No matter how far I’d eventually travel from that simple faith, I’d never be able to completely forsake it. I’d carry it with me through everything that lay ahead. I wish my mother were still alive so I could tell her this: her efforts weren’t in vain; I can still hear her gentle voice reading from that prayer book, as she sat on the edge of my bed and I repeated the words she said, taking them in, feeling the goodness of her love.

March 3, 2014

Hidden Populations: A Post-AWP Invitation

With a little bit of luck, and a lot of waiting as my flight from Chicago was delayed, I finally made it back to Columbus from AWP. I left Seattle with fond memories of the Emerald City, buoyed by the camaraderie of the conference. How wonderful to see so many of my favorite people all in one place and to participate in the ongoing conversation about our writing and our teaching. Only one piece of unfinished business left me a bit unsettled, and I’d like to address it in this post.

About a year ago, Karen McElmurray and I started talking about a conversation in the media that was calling attention to the under-represented status of students from working class families on college campuses. Coming from working class families ourselves, we started to recall our own college experiences, which led us to wonder about the experiences of the students in our creative writing workshops who came from similar backgrounds. At some point, one of us said to the other, “We should propose an AWP panel,” and the other one said, “I’m in.”

So we invited Sonja Livingston, Carter Sickels, and Claire Vaye Watkins to join the conversation on our panel: “Hidden Populations: The Working Class in the Creative Writing Workshop.” On Thursday afternoon, we raised some issues relevant to pedagogy and art-making, as we considered the working class in the writing workshop. It was my hope that we’d have sufficient time at the end of the panel for questions, comments, and the sharing of personal stories. Alas, the best laid plans of mice and. . .

Unfortunately, despite my best planning, we ran long and had only a few minutes to hear one audience member speak eloquently and passionately about her former homelessness and the hope for financial security that her advancement through academia promised. Since then, I’ve heard from a few other folks who were in the audience, and I’m heartened to know that they thought the panel finally opened up a topic that few people had adequately discussed, that topic of social mobility, the promises inherent in it, promises that often go unfilled, and the anger that results from being caught between two cultures. One writer discussed feeling “undereducated in the academy, overeducated at home, judged and isolated in both, and pressured to choose one or the other.” Another writer addressed the financial struggle that she faces as an adjunct instructor, the lack of tenure-track jobs, and the expectations that candidates will have published multiple books. This writer speaks powerfully about fleeing her small town for academia so she might avoid working in its factories and now finding herself earning a smaller wage as an adjunct and with less job security.

I know there are other voices out there, voices that deserve to be heard, so I’d like to use this forum for that purpose. Please feel free to express your thoughts on issues relevant to students from the working class in academia. Claire Vaye Watkins closed our panel by calling for a revolution in order to revise the way we think about what we have to offer our students. It’s crucial that we keep the conversation going so it can eventually lead to action.

I’ll close by quoting from a blog post by Emily Loftis, a Wellesley student from a working class family, as I did during our panel. Emily writes about the anger that she still carries from her experiences at Wellesley, experiences like feeling excluded when a professor asks students to raise their hands if they’ve visited countries x, y, or z, or not being able to do a summer internship because of the need for a paying job. Emily also speaks of the anger that comes from being resented and excluded in her hometown because she dared to dream of more for herself. “My anger is the unspoken side effect of social mobility,” she says, “what no one ever talks about, but I need to talk about it.”

We need to hear more voices like Emily’s and those of the two writers I mentioned in this post.

We can intellectualize and analyze all we want—after all, we’re so good at that in academia!—but it’s those personal voices and stories that humanize the situation and make it impossible to ignore.

So consider this an open invitation. Student loan debt, exclusionary language in the classroom, insufficient MFA student funding, childcare issues, health insurance benefits . . .I’m brainstorming some possible topics. Help me add to the list. Tell me your stories.

AWP is a celebration, but sometimes we have to let the jubilation die down so we can ask ourselves, “What can we do better?”

February 24, 2014

Our Quiet Places

I remember the silence of public libraries before they became places where people talk in normal tones of voice or even chat on cell phones. In summer, the only sound may have been the gentle whirr of an oscillating fan. In winter, there may have been the hiss of a steam radiator. People spoke in whispers when they had to ask the librarian something. It was a quiet place, and in that way it was holy.

I remember the country church that my mother took me to when I was a boy. Sometimes it got so quiet, I could hear the whisk of the tissue-thin bible pages as people searched for scriptures. I could hear a woman’s pocketbook clasp shut as she closed it, having retrieved a handkerchief. I could hear the cellophane wrappers of cough drops being undone and the sound the cardboard fans made as people waved them through the air.

I remember a cemetery deep in the country (I still like to go there) where sometimes the only sounds came from a bobwhite’s two-note call, or from a hickory nut dropping from a tree to land in the grass.

As an only child growing up in the country, I developed an appreciation for solitude and quiet. I walked into the woods and listened to the creek water trickling over sandstone and shale. I moved through prairie grass, lost in daydreams, startled only by the clacking of wings when a covey of quail took flight.

A quiet place is necessary for a writer; at least it is for this writer. I fear it’s getting harder and harder to find those stretches of quietude that allow our imaginations to deepen. I’m also well-aware of the irony of this post that adds to the “noise” around you—noise from social media, e-mail, blogs, etc.

I seem to recall that John Updike said that much of his work began for him while sitting in church. I’ll confess to my own daydreams and flights of fancy while in the midst of a service. “What art offers is space,” Upkike said, “a certain breathing room for the spirit.”

It’s the “breathing room” of the creative process that we have to protect, and that breathing room comes from our quiet places. I fear, though, that modern technology is making it difficult. We are expected to be “connected,” and, therefore, we become part of the noise.

So here’s a simple assignment meant to reclaim our right to shut out the clatter around us:

1. Go to a quiet place.

2. Get comfortable with being alone.

3. Let your mind wander.

4. Let it go where it wants, but pay attention to where it goes.

February 17, 2014

“Enough about Me, Tell Me What You Think about Me”

Today’s post comes from some work I’ve been doing in preparation for a panel that I’ll be on at the AWP Conference at the end of the month. The panel, put together by the fabulous Sue William Silverman, is called “A Memoir with a View: On Bringing the Outside In.” Sonya Huber, Joy Castro, and Harrison Candelaria Fletcher will be the other fine folks on the panel.

For years, I’ve noticed a tendency for beginning writers of personal narratives to forget to make room for the other actors on the stage and to forget that memoirs take place in particular settings and at particular time periods that express particular values. I call this tendency the “Enough about Me, Tell Me What You Think about Me” Syndrome. These writers are in love with the sound of their own voices. They believe themselves to be, to borrow from a popular beer commercial, “the most interesting people in the world.” I’m having a bit of fun here because I don’t think that their narcissism is intentional. It’s merely the result of a lack of storytelling technique that will correct itself over time and with practice.

When I read a memoir, I want to feel like I’m a participant in a life. I don’t want to be kept in the wings, watching. I want to be on stage living what the people in the memoir are living. The narcissistic approach keeps readers at a distance rather than immersed in the events. Although we’re certainly interested in the sensibility of the narrator, we can begin to feel claustrophobic if he or she forgets to take a look outside that self. Although I love and value the art of reflection and thinking on the page that takes place in a good memoir, I confess to starting to lose interest if I’m asked to spend too much time inside the writer’s head. The world starts to close down for me rather than open up. We need to make room for that world, not to diminish ourselves, but to make ourselves larger by seeing what it means for us to interact with this person, this detail, this place, this time period, this action.

As I said above, I believe that this unintentional narcissistic approach is actually a deficiency of technique problem. Its symptoms include a lack of dialogue, a lack of detail, and a lack of action. It can easily be cured with a writing activity, which I prescribe for all of us now.

1. Select a lost object from your childhood, one that you’ve never forgotten, one that you wish you still had. My grandmother had a lady bug pin cushion when I was a child, and to this day I remember that she kept a Charles Percy campaign button stuck to it. Percy was the Republican candidate for Governor in my home state of Illinois in 1964; he narrowly lost to the incumbent, Democrat Otto Kerner. My mother’s family was Republican; my father was a staunch Democrat. I’ve always wondered what my grandmother thought about my mother’s marriage to my father, an event that took place when my mother was forty-one, and that pin cushion and that Percy campaign button invite me to think about that. So what’s your object?

Spend some time writing from this prompt: “I remember. . .” Perhaps, you’ll hit upon a scene in which you’re watching yourself as a child looking at this object, or handling it, or maybe you’ll remember what it was like to watch someone else using it. The important thing is to describe what you see, hear, smell, taste, touch as you travel back in memory.

2. Daydream yourself into a specific memory. It might be one that involves your object, or it might be one that it suggests. If the power of association takes you away from the object, trust that you’re meant to follow. I might recall, for example, the evening my father and my uncle, my mother’s brother, got into a heated argument over politics and how strange it seemed to hear these men, who genuinely liked each other, raising their voices and saying things like, “Herbert Hoover ruined the farmer!” Or “Spend, spend, spend. That’s all a Democrat wants!” What are the people in your memory saying?

3. My uncle finally got up from his chair that evening and said to my aunt, “Get your coat, Myrtle. We’re leaving.” What happened after that? My father, still angry, rehashing the argument, his face red as he paced about our kitchen where my mother, whose views were the same as my uncle’s, cleared the coffee cups and dessert dishes from the table and began to wash them, not saying a word. What actions take place in your memory?

In order to pay attention to detail, dialogue, and characters in action, you’ll have to look outside the self, and you’ll write a scene in which you look at the larger world that may be social (a gathering of relatives), cultural (at a time and in a place where manners were supposed to always trump what one really thought), and political (at a time in the 1960s when our country’s political climate was changing).

In all honesty, I’ve never thought of myself as a political writer, or a cultural critic, or a social commentator. But really, as I hope my lady bug pin cushion has proved, any writer of memoir is all three of these things. The small details of a life contain the social, the cultural, and/or the political.

February 10, 2014

Ten Thoughts about Writing a Memoir

Last week, I posted ten random thoughts about writing a novel. To give equal time to my other genre, I offer these ten random thoughts about writing a memoir.

1. If you want revenge, don’t write a memoir. Start nasty rumors instead. When we write about people, we want to be fair to them even if they weren’t fair with us. We need to look at them, and ourselves, from as many different angles as possible in an attempt to understand the sources of the behavior. Writing a memoir is a search for understanding.

2. If you want to lie, don’t write a memoir. Perhaps my ten thoughts about writing a novel might prove useful. Writing a memoir requires a faithful allegiance to facts. If your grandmother is still living, please don’t kill her off for the sake of the narrative in your memoir. Stay true to the facts of your life unless you can establish a reason for invention and imagination and can cue the reader that you’re taking liberties with what actually happened.

3. If you expect to have an infallible memory, don’t write a memoir. Go on Jeopardy instead and make a boat-load of money. Memory is imperfect, and we have to accept that. The act of remembering becomes a story itself. Do you think you have a memory of something but aren’t sure? Admit that to the reader and then speculate on why you think this thing might have happened. The speculation will take you more fully into your material.

4. If you don’t want to think, don’t write a memoir. Watch mindless television programs instead. Memoirs allow us to dramatize, but they also ask us to observe, question, speculate, and attempt answers.

5. If you want to be certain, don’t write a memoir. Practice elementary arithmetic instead. 1+1= 2. Writing a memoir is a way of thinking aloud on the page. We usually start from a place of not knowing. Something about our experience haunts us and demands our attention because it’s in some way unresolved.

6. If you want to tie things up in a neat bow, don’t write a memoir. Take a gift-wrapping class instead. Our lives are messy and not necessarily driven by cause and effect. We can’t invent things to give our lives a more symmetrical structure. A memoir may not have a resolution, but it may derive its power from a deepening of the occasion for writing. What is it that first brings the writer to the page? How does the act of inquiry develop the character of the writer? What does he or she come to know?

7. If you want everyone to love you, don’t write a memoir. Start handing out free cash instead. All that truth telling I’ve been talking about? Well, it usually requires that you say some very hard things about yourself and about others. Some people will be angry because they don’t like the way you portrayed them. Others will be angry because they don’t have enough space in your book. Still others will be mad because they’re not in the book at all. Make peace with the fact that after your memoir is published some people will be upset with you. All you can do, as I’ve said above, is to treat everyone fairly.

8. If you want to include everything, don’t write a memoir. Sample everything at the Hometown Buffet instead. When we write a memoir, it’s impossible to include everything from our lives, even the smaller slices of them. We have to choose only the telling moments that are central to the material we’ve come to the page to explore.

9. If you resist making a scene, don’t write a memoir. Sit quietly in a church instead. Memoirs are made up of particulars and scenes, in which people speak and act. We need to find the moments from our lives that affected us in some way, and we need to dramatize them on the page. This scenic writing allows readers to feel as if they’re participating in your life rather than merely watching from the audience.

10. If you don’t want to change, don’t write a memoir. Write a manifesto instead. Writing a memoir will change you. I promise. It will change you in ways you couldn’t have predicted. It will change you because you’ll have to watch yourself live through the significant moments from your life, but this time you’ll have the perspective offered by distance and time. It’s a perspective that will offer you the chance for discovery and insight. When I reached the end of the first draft of my first memoir, From Our House, I wept, and I felt the anger that I’d inherited from a life lived in the midst of my father’s anger, begin to ebb. Writing that book gave me control over my own anger. I looked at my father’s life in a way I never had until I started to shape it on the page. I looked at the life we had together with new eyes. I saw and felt things I never could have imagined, and I wasn’t quite the same person at the end of that draft as I was at the beginning. That’s the power of memoir. It sweeps you through the past and into the future.