Lee Martin's Blog, page 25

February 22, 2021

And Then What Happened?: Plot in Short Fiction

Jhumpa Lahiri’s story, “A Temporary Matter,” opens with this sentence: “The notice informed them that it was a temporary matter: for five days their electricity would be cut off for one hour, beginning at eight P.M.” Eerily resonant with the shocking news out of Texas this past week about the cold weather and the failure of the electrical grid, Lahiri’s story starts in the aftermath of a snowstorm that has brought down a line that needs to be repaired. Hence the one-hour blackouts meant to continue for five days.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s story, “A Temporary Matter,” opens with this sentence: “The notice informed them that it was a temporary matter: for five days their electricity would be cut off for one hour, beginning at eight P.M.” Eerily resonant with the shocking news out of Texas this past week about the cold weather and the failure of the electrical grid, Lahiri’s story starts in the aftermath of a snowstorm that has brought down a line that needs to be repaired. Hence the one-hour blackouts meant to continue for five days.

It’s such a simple premise, yes? A wrinkle in the regular come-and-go of the lives of a married couple—the wife, Shoba, and the husband, Shukumar. Just a little something to vary the routine of their days. That routine, we quickly learned has been influenced by the fact that six months before the story begins, their baby was stillborn while Shukumar was away at a conference. Since then, Shoba and Shukumar have been drifting apart. Now, with the nightly power outages, Shoba suggest that they “say something to each other in the dark.” Something neither has ever told the other. Their secrets start out innocently enough. On their first date, Shoba checked his address book to see if he’d written her in; Shukumar forgot to tip the waiter the first time he and Shoba went to dinner and went back the next morning to correct the oversight. Each night, the secrets get a bit more significant, and as they do, the couple draws closer together. I’ll refrain from revealing the final round of secrets so as not to ruin the story for anyone who hasn’t read it. Suffice it to say, the exchange is heartbreaking and devastating. At the end of the story, Shoba and Shukumar tell each other things they never could have imagined saying.

This all happens because something out of the ordinary occurs—the blackouts—and because Lahiri fills in the back story of the stillbirth. Our characters are always carrying something from their pasts with them when our stories begin. That something influences the action of the story, and the action leads the characters to a moment beyond which they’ll never be the same. Often an indirect route to the heart of the story is the best way forward. A power outage in the Lahiri story creates an opportunity for Shoba to invite Shukumar to exchange secrets. The exchange of those secrets leads the couple to a place from which there’s no return. “What is character but the determination of incident?” Henry James says in “The Art of Fiction.” “What is incident but the illustration of character?” We might say it this way: Character creates plot, and plot reveals character.

I worry sometimes that plot is diminished or underappreciated these days. Maybe it’s a result of our times where there seems to be no logical sequence of events, no cause and effect. With all the noise and fear around us, it’s easy to believe this to be so, but I retain a faith in the pattern of a world in which people make choices that lead to certain actions that lead to consequences. As Margaret Atwood says, “All fiction is about people, unless it’s about rabbits pretending to be people. It’s all essentially characters in action, which means characters moving through time and changes taking place, and that’s what we all ‘the plot.’”

I’ve always loved the way a good story can give shape to chaos. Starting with a simple variation in the ordinary can put a plot into motion. A character’s actions can sustain it. A relevant back story can give the action significant meaning all the way to the resonant end of a sequence of events. The actions don’t have to be grand in scale; they only have to be memorable for the people involved. Plot needs to take characters and readers to places neither they nor we could have seen coming even if we’d tried—those places of inevitable surprises, the ones that catch us by the throats and make us look at the truths of what it is to be alive on this earth.

The post And Then What Happened?: Plot in Short Fiction appeared first on Lee Martin.

February 15, 2021

A Valentine’s Day Wish for Writers

Here on Valentine’s Day, a winter storm is approaching. Actually, two storms are meant to hit a wide swath of the country this week. It’s sunny right now here in central Ohio, and people are out in force, laying in supplies. Tonight, though, the snow and ice will be here, and then the temperatures will plunge. We’ll brace ourselves for a second round later in the week.

Here on Valentine’s Day, a winter storm is approaching. Actually, two storms are meant to hit a wide swath of the country this week. It’s sunny right now here in central Ohio, and people are out in force, laying in supplies. Tonight, though, the snow and ice will be here, and then the temperatures will plunge. We’ll brace ourselves for a second round later in the week.

Already, I’m anticipating the contented feeling—all right, maybe even a bit of a smug feeling—that comes from not having to drive anywhere in the bad weather. I’m grateful for shelter with Cathy and our orange tabby, Stella the Cat. I’m thankful for food and warmth. I embrace the hunkering down and the surrendering to nature’s force that teaches us sometimes all we can do is wait.

It’s a lesson I wish I’d learned when I was a young writer. I was too eager for my writing to be validated by my teachers and the editors at various literary journals who were rejecting my work. I was impatient. I was prone to the doubt and despair that creeps in when we wonder whether we’ll ever be good enough. I’d yet to accept the fact that I had no control over how a teacher or an editor would respond to my work. I only had control over the process of creating that work, and the truth is sometimes the process takes longer than we wish it did. Still, the focus of our energy should be on the craft and not on the end result of our process. All of the worries about validation only create negative energy. What we need is positive energy bred from our embrace of what we truly love—the craft itself.

We can’t hurry that craft—our deepening of it will come as it comes—but we can hasten that deepening. We should read the work of others slowly and thoughtfully and always with the question of how that work got made. Everything written is a result of a series of artistic choices a writer made. Those choices create specific effects. Being able to identify the choices and articulate the effects deepens our understanding of craft and makes our own practice more fruitful.

We can also give our work the time it needs to mature. Instead of rushing it out into the world, we can make ourselves wait until the work has fully revealed itself through the act of revision. Often it takes time for an individual work to find its complexity and its resonance. Likewise, it often takes time for us to feel and understand why a piece matters greatly to us. Sometimes we have to wait until we know the personal element that gives the piece the urgency it needs in order to express our truths to the larger world.

A storm like the one that’s coming always slows me down, teaches me to be patient, and narrows my focus on what I can control. I eliminate everything I can’t. On this Valentine’s Day, I wish a similar gift to all of you, particularly those of you who are just starting out on your writer’s journey, a trip I always describe as a lifelong apprenticeship. Give yourself over to your love. Shut out the noise and distraction of your own selfish desires. Let the writing itself be the thing that matters most. Listen to it. Respect it by dedicating yourself to the study and practice of your craft. Be kind to yourselves. Embrace the truth that the journey will always take you where you’re meant to go.

The post A Valentine’s Day Wish for Writers appeared first on Lee Martin.

February 8, 2021

First Date: A Valentine

A mile east of Sumner on Route 250, the entrance to Red Hills State Park beckons. This is the land of night fisherman, weekend campers, and teenage lovers. When a boy takes a girl to Red Hills. . .wink, wink. . .well, everyone knows it’s not just to talk.

A mile east of Sumner on Route 250, the entrance to Red Hills State Park beckons. This is the land of night fisherman, weekend campers, and teenage lovers. When a boy takes a girl to Red Hills. . .wink, wink. . .well, everyone knows it’s not just to talk.

But that’s exactly what we do. Cathy and I—in the front seat of my Plymouth Duster, at Veterans’ Point, a spit of land that looks out over the lake and the restaurant on the other side. In the dark of the night, after leaving the Avalon Theater, where we’ve seen American Graffiti, we talk. There are a number of points and coves like this one throughout the park—secluded places off the main roads where a car can sit undetected—but for some reason I’ve chosen this one.

I’m content to sit in my car with Cathy, talking while the minutes pass. What do we talk about? I haven’t a clue. I remember the sound of peepers from the lake, the distant call of a whippoorwill, the night breeze cool enough for us to be glad for our jackets, the faint laughter from the campgrounds just up the road. Through the trees, still bare-limbed here in early spring, I can see campfires burning down to embers, can smell their smoke. But what we talk about, I can’t begin to recall. I only remember that we talk and talk. It’s easy for us to be in each other’s company. Cathy gets very animated when she talks, and looking back now, I imagine it’s because she’s a little nervous as am I because, of course I want to kiss her but I don’t because maybe she doesn’t really want me to—after all, we’re just talking. We’re not sitting close together. We’re not even holding hands. How am I to know whether she’ll welcome a kiss?

Then she’s about to say something—what, I don’t remember, only that it’s something that she can’t say unless she has something wooden to knock against—that old superstition—so as not to jinx it, and I get very involved with finding something in the car that might have a bit of wood, and I remember I have an ice scraper under my seat that has a wooden handle. I retrieve it and hold it out to Cathy so she can knock on it, which she does, and then she says the thing she’s been wanting to say and I bend down to put the scraper back under the seat, and when I raise my head, I see Cathy has her hand on the Duster’s horn, which is actually the pliant rubber center of the steering wheel.

“What’s this?” she asks, and she gives the horn a squeeze. The resulting blast sounds so loud in the otherwise quiet night.

“My horn,” I say.

She takes her hand from the horn, and as she begins to draw back her arm, I grab it and pull her toward me. Just like that we’re kissing, and it’s the most wonderful kiss I’ve ever had. Her hand is on the back of my neck. My arm is around her waist, and when the kiss is done, I press her to me, and we hold on a good while.

I could tell her I love her—when I fall, I fall fast and hard—but what sort of thing would that be to say on a first date? Instead, as we draw back from each other, our hands still touching shoulders, arms, fingers, I gaze into those blue eyes, and I’m powerless to resist whatever hoo-doo she’s throwing my way. Red Hill proper is the highest point between Cincinnati and St. Louis. On that hill is an open-air tabernacle and a lighted cross atop a tower. Each Easter Sunday, the local churches put together a sunrise service. A place of the spirit. A place for believers. I put my faith in what I feel for this blue-eyed girl, who whispers to me now, “It’s almost midnight,” and even though I don’t want to, I know I have to drive her home.

Do I kiss her goodnight when we get there? I can’t recall, but I’ve never forgotten that first kiss, the one we waited until the last minute to have, the one whose memory carries me to my home that night in 1974 and into my bed, feeling like I’ve never quite felt before. I know there are those who will call what I’m feeling infatuation or hormones, but I stand behind this: I fell in love with Cathy Hensley that night. I was helpless. It’s as simple as that.

The post First Date: A Valentine appeared first on Lee Martin.

February 1, 2021

Subtext and Irony

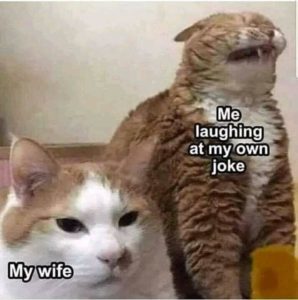

My dear wife Cathy recently posted a meme on Facebook that featured two cats. One cat has its ears flat, its eyes closed, its lips pulled back, and it’s easy to believe the cat is laughing. If you don’t believe that, there’s a caption to convince you: “Me laughing at my own joke.” Beside this cat is another cat who’s clearly not impressed. This cat is staring straight ahead, a somber look on its face as it totally ignores the first cat. Again, a caption lets us know what the meme intends. This caption reads, “My wife.” When Cathy posted this, she tagged me, and she said, “This happens frequently at our house.” So indeed the first cat is intended to be me, and the second cat is meant to be Cathy, who’s clearly not always impressed with my jokes.

My dear wife Cathy recently posted a meme on Facebook that featured two cats. One cat has its ears flat, its eyes closed, its lips pulled back, and it’s easy to believe the cat is laughing. If you don’t believe that, there’s a caption to convince you: “Me laughing at my own joke.” Beside this cat is another cat who’s clearly not impressed. This cat is staring straight ahead, a somber look on its face as it totally ignores the first cat. Again, a caption lets us know what the meme intends. This caption reads, “My wife.” When Cathy posted this, she tagged me, and she said, “This happens frequently at our house.” So indeed the first cat is intended to be me, and the second cat is meant to be Cathy, who’s clearly not always impressed with my jokes.

“Well, I’m not,” she said when we talked about it. “You think things are hilarious that I don’t find funny at all. Why is that?”

I’ve been thinking about that question all day, and as with most things, I have to connect it to my life as a writer in order to have any clarity at all.

To be clear, I don’t think of myself as a funny writer, but I do think of myself as a funny person. Even though I don’t deliberately try to use humor in my work, sometimes it creeps in. In my story, “The Dead in Paradise,” a husband who feels he’s disappointed his wife, says to her, “You know, you could have done a lot better than me.” The wife says, “Nah, baby, I did the best I could.” To me, there’s something about subtext that makes this humorous. The husband has just put himself in a place of vulnerability, admitting that he’s not been the husband he thinks his wife deserves, and she responds with a subtle slap in the face. She did the best she could, she says, but what she doesn’t say directly is, of course, he’s disappointed her. In fact, he’s never been a good husband. He’s always come up short. She’s always had to settle. There’s also an unintentional self-accusation in what she says. She did the best she could. By saying this, she diminishes herself at the same time that she slyly agrees that the husband could be a better man. As Jessamyn West says, “A taste for irony has kept more hearts from breaking than a sense of humor, for it takes irony to appreciate the joke which is on oneself.”

This indirect approach to comedy often comes to play in dialogue, and it reminds us that what’s unsaid beneath what is said, often carries a powerful truth in a witty or ironic way. As George Saunders says, “Irony is just honesty with the volume cranked up.” Subtext can let a reader in on a joke that the listener, and sometimes even the speaker, isn’t aware of. A resonance results from the juxtaposition of the thing said with the thing kept silent. I spend my days thinking about how to show in what I write the masks people wear and the truer people they are behind those masks. Verbal subtext and irony is but one way I try to strip those masks away. Because I spend my time doing this, maybe I’m more receptive to verbal humor, particularly the kind that unintentionally reveals more than one aspect of a character or a situation.

In case you’re curious, Cathy doesn’t find humor in the exchange between the husband and wife in “The Dead in Paradise.” “If the wife said something more direct,” she says. “Something more obviously insulting to the husband. “Oh, you mean like the cat meme,” I say. The comment I posted on that meme? “I am not amused.” At least Cathy thought that was funny.

The post Subtext and Irony appeared first on Lee Martin.

January 25, 2021

Writers Setting the Stage: The Importance of the Authentic Details

In the opening of the 1984 film, Country, starring Sam Shepard and Jessica Lange, there’s a shot of a kitchen table, and on that table is a set of waffle glass salt and pepper shakers with aluminum tops. I still remember the chill of recognition I got right there in the movie theater when I saw them. I could have closed my eyes at that point and pretty much guessed the other items in that farm house, the landscape outside, and the customs and values of the people who lived there. Country was one of the first films I saw that seriously tried to depict the rural Midwest in the midst of a farm crisis. It was one of the first films I saw that treated the people and the place from where I came with authenticity. Those salt and pepper shakers hooked me from the beginning, and as soon as I saw them I knew I’d trust the filmmaker to take me wherever he wanted me to go.

In the opening of the 1984 film, Country, starring Sam Shepard and Jessica Lange, there’s a shot of a kitchen table, and on that table is a set of waffle glass salt and pepper shakers with aluminum tops. I still remember the chill of recognition I got right there in the movie theater when I saw them. I could have closed my eyes at that point and pretty much guessed the other items in that farm house, the landscape outside, and the customs and values of the people who lived there. Country was one of the first films I saw that seriously tried to depict the rural Midwest in the midst of a farm crisis. It was one of the first films I saw that treated the people and the place from where I came with authenticity. Those salt and pepper shakers hooked me from the beginning, and as soon as I saw them I knew I’d trust the filmmaker to take me wherever he wanted me to go.

In our writing, the small, authentic details are everything. They create the world and its people. They procure the trust of the reader. They say, here’s a very particular world, won’t you please come in?

So here are a few questions for you:

Are you writing about the worlds you know best? I know when I first started out, I didn’t trust that anyone would be interested in my small towns and farming communities. What I learned was if I couldn’t make those places interesting on the page, I’d never come close to portraying places I knew less well. We have to write the places and the people with whom we’re the most intimate.

Are you taking the time to paint your worlds with the smallest of details? If you don’t know the small details, like waffle glass salt and pepper shakers, you’ll never be able to notice the truths of character and place and situation that those small details contain.

Do your landscapes express your characters? The contour and shape of a landscape often connects with the type of people who occupy it. My farming community in the Midwest, for instance, is comprised of gravel roads that run at right angles, creating a grid that can be as rigid as the people often are. The flat land underneath an endless sky, though, can stretch to the horizon, and represent the open hearts of hard-working people who would do anything they could to help someone in need.

We need to take care with our stage settings. Like any good theatrical set dresser, we have to get all the details right so we can fulfill the first obligation of all writing, to convince the readers that the world on the page is an authentic one. When you think of each thing you write, can you think of a single object that creates this authenticity, the object that persuades readers that all you have to tell them is true? Remember, an object like a waffle glass salt and pepper shaker isn’t a small thing. It’s everything.

The post Writers Setting the Stage: The Importance of the Authentic Details appeared first on Lee Martin.

January 18, 2021

Memoir and the Dangers of Nostalgia

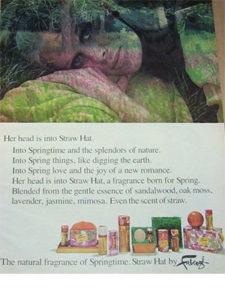

It’s 1974, and I’m eighteen years old. I drive a slant-six Plymouth Duster, and I wear my hair long and my jeans tight. I hang out at John Piper’s pool hall, where I play the pinball machines. When the weather’s good, I play basketball on the schoolyard. My game has never been better. I’m young and strong and a little cocky. I like to cruise the streets of my small town just to see who I can see and, of course, to let them see me. I have a girlfriend named Cathy, and I have that head-over-heels, pie-in-the-sky, catch-me-I’m-falling-in-love feeling about her. I have no way of knowing that thirty-eight years later I’ll marry her. At the time, I only know the scent of her Straw Hat perfume, a scent she claims now she doesn’t recall ever wearing, but I stand by my memory. I remember that perfume, and how it felt to hold her in my arms, and the sway of her hips, and the way she whistled her “s’s” when she called me, “Sweets.” These are the days of my glorious youth, days that now can seem so distant but at the same time can seem so near.

It’s 1974, and I’m eighteen years old. I drive a slant-six Plymouth Duster, and I wear my hair long and my jeans tight. I hang out at John Piper’s pool hall, where I play the pinball machines. When the weather’s good, I play basketball on the schoolyard. My game has never been better. I’m young and strong and a little cocky. I like to cruise the streets of my small town just to see who I can see and, of course, to let them see me. I have a girlfriend named Cathy, and I have that head-over-heels, pie-in-the-sky, catch-me-I’m-falling-in-love feeling about her. I have no way of knowing that thirty-eight years later I’ll marry her. At the time, I only know the scent of her Straw Hat perfume, a scent she claims now she doesn’t recall ever wearing, but I stand by my memory. I remember that perfume, and how it felt to hold her in my arms, and the sway of her hips, and the way she whistled her “s’s” when she called me, “Sweets.” These are the days of my glorious youth, days that now can seem so distant but at the same time can seem so near.

I’m recalling those days now because I want to say something about what it takes to look clearly at the various versions of ourselves when we write memoir. We have to look beneath the nostalgic recollection of our younger days in order to see the layers of truth that nostalgia tries to hide. We have to see the details that we tried our best to conceal when we were living those younger days.

The truth is my Plymouth Duster had a 198-cubic-inch, 125-horsepower engine that was built for economy and not speed. It’s true I wore my hair long and my jeans tight, but my hair was often a mess of thick waves that Cathy once tried to tame with a Ronco Trimcomb that my family owned. It was so dull and pulled so badly, I was nearly in tears by the time she was done. The sneakers I wore when I played ball often had holes in the bottoms, and I don’t know why I didn’t buy a new pair. The grain on the ball we used was so slick it was hard to shoot with any accuracy. I wasted so much money in that pool hall because I didn’t want to go home. I needed a place to be. The only thing completely true in the opening paragraph of this post is the way I felt about Cathy—that and the Straw Hat perfume, which I’ll continue to insist is accurate.

I stand by what I felt about Cathy—and continue to feel to this day—but to write truly about that time period, I’d also have to write about how out of place I felt when I first started attending the nearby community college—how I’d often sit in my car when I didn’t have a class, writing poems and feeling insecure. I’d also have to write about what it was like to be the only child of older parents—my mother was sixty-four in 1974, and my father was 61—and the fear I had that they would die while I was still young. My father and I had finally reconciled after a difficult childhood and early teen years, but I carried with me the memory of his belt against my skin and the ugliness of our words. I’d have to write about how desperate I was to find someone who would treat me with tenderness, and how that fact made me especially susceptible to falling in love.

We can’t romanticize ourselves or our pasts when we write memoir. We have to be honest. We have to come clean. We have to see the truths of our lives that lurked beneath the images we tried to present to the larger world. We have to be willing to put the details on the page that reveal the inner lives we lived. The contrast between the way we’d like to remember our younger selves and the truths we have to confront can make for powerful writing. We can’t let nostalgia seduce us. There’s always something more truthful on the other side of it.

The post Memoir and the Dangers of Nostalgia appeared first on Lee Martin.

January 11, 2021

Struggle and Empathy

We’re nearing the middle of January, which means the end of the month is in sight. Given the challenges of the pandemic, I thought it interesting to revisit this post from a year ago.

We’re nearing the middle of January, which means the end of the month is in sight. Given the challenges of the pandemic, I thought it interesting to revisit this post from a year ago.

A native Midwesterner, I’ve always thought of winter as an endurance test, and each signpost along the way—the end of January, Valentine’s Day, the NCAA basketball tournament, etc.—a mark that brings us closer to spring. Here in the Midwest, we earn our springs. We go through the cold and snow and ice, and because we endure, we deserve the warm days that finally are ours. I admit our winter this year has been fairly mild, but still, even the gray and damp attacks the spirit and we find ourselves longing for sun and flowers and trees and shrubs in bloom and long hours of light.

Our fictional characters want the same thing—to live and prosper in the grand lives we all deserve. The characters in our nonfiction are no different. They, too, want to live lives of splendor. The problem, of course, is there are always struggles along the way. In nonfiction, we’re sometimes so wounded by the insensitive acts of others we have trouble finding our common humanity. We have difficulty imagining the pain of those who have hurt us. It’s understandable, of course, but I’m convinced the effort to empathize is worth it, not only for the sake of the writing, but also for our own sakes. If you’re writing a memoir, for instance, what might you do to humanize someone who hurt you? Could you, perhaps, recall a moment of vulnerability for that person? Maybe it’s a moment when that person didn’t realize you were watching them. Maybe you found some sort of document—a letter, a shopping list, a doodle—anything that gives you a glimpse into what that person may have been carrying that contributed to their poor behavior. We have to make the attempt to better understand people’s actions, so we can come to an awareness that those who hurt us aren’t so different from us. Maybe someone tells you a story about a relative, for instance, that surprises you with sympathy for that father, mother, sister, brother, etc. Or maybe you challenge to imagine your relative as a small child. Put that person into an imagined scene in hopes of seeing something you ordinary wouldn’t.

We all have our struggles, but we all have the capacity for love, forgiveness, and deeper understanding.

Which brings me to characters in fiction and the need to let our main characters create their own trouble. In nonfiction, we have to reckon with events that happen, events that are sometimes random and without logic. In fiction, though, we’re money ahead if we let our characters’ action cause their problems. Characters should create their own fates. Once we have a character into some sort of troubling situation of his or her own making, we shouldn’t hesitate to complicate the trouble even further, thereby increasing the intensity of the struggle. Don’t let the characters off the hook easily. Complicate the trouble, so the character has to make choices. Each of those choices should put increased pressure on the character until the highest moment of intensity leads to resolution.

Here’s a writing activity for fiction writers. A character is supposed to deliver a message to someone but decides not to. What sort of trouble does that decision create? What does the character do to try to get out of trouble?

And for nonfiction writers? Remember a time when you were supposed to do something but didn’t. What sort of trouble did your decision create for you? How do you feel about your decision as you look back on it from your present perspective? Does looking back give you any insight into yourself or others?

“Never underestimate the pain of a person,” the actor, Will Smith, says, “because in all honesty, everyone is struggling. Some people are better at hiding it than others.” Amen. Struggle is there to test people, both in fiction and in real life. In fiction, characters create their own trouble. In nonfiction trouble often happens to us. In both cases, the act of empathy is the greatest gift we can give.

The post Struggle and Empathy appeared first on Lee Martin.

January 4, 2021

We Are Writers

Here at the start of a new year, I’m thinking of how much 2020 asked of us, not only in our day-to-day lives but in our writing lives as well. As I’ve said in other places, some of us have struggled to write and some of us have immersed ourselves in our writing either as a way to escape the reality around us or to understand what it has to teach us about ourselves, others, and the world around us. No matter whether we’ve been productive or not, it’s okay as long as the choices we’ve made have led us somewhere necessary to our survival. If you haven’t written much, or if you have, don’t feel guilty. We’ve just closed the door on a year unlike any other, and now, as we move forward into 2021, we may feel in need of motivation, or at least we may need a way of thinking about what it means to us to call ourselves writers.

Here at the start of a new year, I’m thinking of how much 2020 asked of us, not only in our day-to-day lives but in our writing lives as well. As I’ve said in other places, some of us have struggled to write and some of us have immersed ourselves in our writing either as a way to escape the reality around us or to understand what it has to teach us about ourselves, others, and the world around us. No matter whether we’ve been productive or not, it’s okay as long as the choices we’ve made have led us somewhere necessary to our survival. If you haven’t written much, or if you have, don’t feel guilty. We’ve just closed the door on a year unlike any other, and now, as we move forward into 2021, we may feel in need of motivation, or at least we may need a way of thinking about what it means to us to call ourselves writers.

I’ve been writing for over forty-five years, and there have been numerous times when I’ve been tempted to stop. When I was a young writer, despondent because of a steady stream of rejections, I thought how nice it might be to give up the writing life for a more ordinary way of being, one in which my ego wasn’t tied to the gatekeepers who over and over told me no, a life where I could work a job and leave it behind when quitting time came. Then I realized that writing wasn’t just what I did, it was who I was. If I stopped, I’d be someone else, and that someone else wouldn’t be anywhere close to the person I really was. Without writing, I’d be living the life of an imposter. I had to ask myself who I was, and the answer was I was a writer no matter if anyone wanted to publish what I wrote. So I kept on.

Another truth was I enjoyed writing, and I’ve kept enjoying it over all these years. Nothing gives me more pleasure than moving words about on a page, and I don’t need any external validation to do that. Oh, sure, it’s nice when it comes, but the simple truth is it has nothing to do with what happens for me when I’m alone in my writing room seeing what words can do to capture all that mystifies and astonishes me about this complicated world in which we live.

It’s true that for the most part the larger world doesn’t care about what we do. Accepting that fact can be freeing. You know the value of the hours you spend writing. Don’t let anyone take away the feeling that you have when you do that work.

There are times when I don’t write, and I’ve gotten better, as I get older, at forgiving myself for these down times. Sometimes we simply have to recharge. I know that no matter how long I’m away from my writing room, the life of the writer will always be with me, the work will always be waiting, the blank page will always be welcoming.

The hardest truth we writers have to accept is no one cares if we quit. Once we realize that, we can free ourselves from what constrains us—the apathy of the world, the blows to our ego, the uncertainties when it comes to our talents, the fears that we won’t be good enough, and on and on—and we can write with pleasure because it’s who we are. We can keep doing the good work that we’ve been called to do.

The post We Are Writers appeared first on Lee Martin.

December 28, 2020

A New Year in the Pandemic

I’m writing this on the last Sunday of 2020, the year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus that has taken over a million seven-hundred lives worldwide, the virus that has totally disrupted our normal come-and-go. We wear facial masks now—at least we should—and we keep our distance from one another, and we avoid gatherings, and we wash our hands, and still the virus surges. We make choices to avoid in-door dining. We make hard choices about whether to see family and friends. Last semester, I taught my classes online from home, and I’ll do the same this coming semester. and still the virus surges. We have two vaccines now to give us a glimmer of hope as we head into 2021, but for now the virus continues to surge. I’ll admit it’s sometimes tempting to let pessimism have its rule, but I’m trying hard to stay on the brighter side of my view to the future.

I’m writing this on the last Sunday of 2020, the year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus that has taken over a million seven-hundred lives worldwide, the virus that has totally disrupted our normal come-and-go. We wear facial masks now—at least we should—and we keep our distance from one another, and we avoid gatherings, and we wash our hands, and still the virus surges. We make choices to avoid in-door dining. We make hard choices about whether to see family and friends. Last semester, I taught my classes online from home, and I’ll do the same this coming semester. and still the virus surges. We have two vaccines now to give us a glimmer of hope as we head into 2021, but for now the virus continues to surge. I’ll admit it’s sometimes tempting to let pessimism have its rule, but I’m trying hard to stay on the brighter side of my view to the future.

My efforts to stay positive took a dark turn early on the morning of December 8, when my wife Cathy, in excruciating abdominal pain, said, “I think you’re going to have to call the ambulance.”

I know there are people who have suffered so much this year, have suffered more than Cathy and I did that morning and the ten days of hospital stay beyond it, but I also know the devastating feeling of having the EMTs take the love of my life away from me, and I, due to COVID, being unable to follow.

Cathy had emergency surgery that evening, and I waited by the phone for someone from the hospital to call. How could I not imagine what it’s like for those whose loved ones have had to be hospitalized with COVID, or those whose family members have been isolated in nursing home or care facilities? Cathy told me later, once we were on the other side of her emergency, that she never once thought that she wouldn’t come home. Whenever that thought came to me in the time we were apart, I pushed it away, unwilling to allow that possibility. Instead, I exercised when I could, wrote when I could, read when I could, talked to Cathy when she was able to talk, and took care of our home and our orange tabby, Stella the Cat. All I could do was let the days go on. We learn this as we get older—on occasion, all you can do is give yourself over to the forward movement of time.

Finally on December 18, Cathy was strong enough to come home. I delighted in her first words to me when I collected her at the hospital entrance: “I’m ready to blow this Popsicle stand!” And blow it we did.

I’ve always given thanks for each minute I have with Cathy, but even more so now when I think of all the COVID patients who didn’t get to come home and all the family members who’d give anything to have one minute more with their loved ones, or at least to have been able to be with them when they passed.

What this has to do with writing, I’m not sure, but maybe there’s something here about love and kindness. I know it’s been a tough writing year for many of us, and for others it’s been a year of escaping into our work and producing pages. No matter the way the pandemic has affected our , writing, we should pause to appreciate each minute that’s ours and to fill those minutes with whatever we think will sustain us. We should be kind to ourselves and to others. We should face reality and yet not give in to despair. As the dark days of January and February descend, we should remember the spring that lies beyond the darkness. These coming days may be grim indeed, but I give thanks that Cathy came home, and I do my best daily to choose hope over despair, work over idleness, and love, always love.

The post A New Year in the Pandemic appeared first on Lee Martin.

December 21, 2020

Shaping a Piece of Writing: More Revision Tips

This week of Christmas, I’m thinking of the trees we used to cut in our woods on the farm, cedar trees that we’d carry to the house and put in a stand at the window in our front room. Those trees were unruly, left to grow the way nature would have it, so unlike the nicely shaped trees for sale at tree farms or nurseries or grocery stores or lots to benefit the Jaycees, the Boy Scouts, the Lions Club. I can only remember one time when my father bought a tree at one of those places, and then our Christmas tree looked like the ones I saw on television.

This week of Christmas, I’m thinking of the trees we used to cut in our woods on the farm, cedar trees that we’d carry to the house and put in a stand at the window in our front room. Those trees were unruly, left to grow the way nature would have it, so unlike the nicely shaped trees for sale at tree farms or nurseries or grocery stores or lots to benefit the Jaycees, the Boy Scouts, the Lions Club. I can only remember one time when my father bought a tree at one of those places, and then our Christmas tree looked like the ones I saw on television.

I had no thought of the people who worked to make sure those store-bought trees had that perfect shape, but years later, when I was a teenager, I became one of those people. I spent two summers working on a local Christmas tree farm, spending my days shaping red pines, white pines, and Scotch pines. Looking back on those days now, I realize I was acquiring skills that would one day contribute to my life as a writer. More simply put, shaping a pine tree can help us think about revising a piece of writing.

The first thing I learned was that pine trees, when left to grow naturally, don’t have that single leader at the top, the one we eventually use for the star or some other type of topper when we decorate. Instead, the tree can have a number of possible leaders. My first step, when I was working on the tree farm, was to choose the leader that would be the best one and to cut the others away. When revising something we’ve written, we should think about the very last move of the piece. Where does it land? What gives it its resonance? What surprises does it contain? What rises at the end? The final move usually conveys the intention of the piece. That’s your leader. That’s the thing you’ve come to the page to say. If there are competing leaders, cut them, so the single thread of the piece will have more space to stand out.

The second step in shaping a pine tree is to, as my boss always said in his Cajun accent, “Make it look like an upside down ice cream cone.” To do that, you have to stand to the side and cut away—sometimes with shears, sometimes with a machete—anything that doesn’t fit into the shape you envision. So it is with what we write. Once we know its intention, we can cut out anything that doesn’t contribute. Once we know our landing place, we can ask ourselves how everything that comes before is making a resonant end possible. If something isn’t helping that end rise, we can get rid of it.

I understand that even the big Christmas trees that stand in Rockefeller Plaza in New York City, often need additional greenery added to fill in some of the empty places and make the tree look full. Similarly, when we revise, we need to ask ourselves what’s missing. What still needs to be written to make our landing place seem surprising and yet inevitable. Are there new scenes waiting to be written? Does the setting need filling out? What about your characters? When it comes to them, have you missed a necessary layer? What about the pace? Are there places where the piece needs to slow down or move more quickly? And the language? Could the dialogue be more artful? Is the tone appropriate? Have you taken full advantage of details and images? Have you created the right atmosphere from which your end can rise?

I offer these questions to help you revise. You’ll probably want to add your own to the list. Here at Christmas, I think of how my own early drafts, like those cedar trees I remember from my childhood, are often disorderly. I also remember how I spent hours in the heat and humidity of summer shaping those pine trees so come Christmas families could enjoy them. Revision takes a similar effort as we do what we must—identify, cut, and fill—to create something that will resonate with a reader. I wish you all the best this holiday season.

The post Shaping a Piece of Writing: More Revision Tips appeared first on Lee Martin.