Lee Martin's Blog, page 19

April 18, 2022

Music on the Page

Here on Easter Sunday, I’m thinking about sounds from the Sundays of my childhood. The whisper of the tissue-thin pages of Bibles being turned in church, the creaking of the wooden pews as someone settled their weight or leaned forward in prayer, the sonorous voice of the man who sang with the spirit that filled him. Psalm 100 told us to “make a joyful noise,” and we did the best we could.

Here on Easter Sunday, I’m thinking about sounds from the Sundays of my childhood. The whisper of the tissue-thin pages of Bibles being turned in church, the creaking of the wooden pews as someone settled their weight or leaned forward in prayer, the sonorous voice of the man who sang with the spirit that filled him. Psalm 100 told us to “make a joyful noise,” and we did the best we could.

And sometimes there were the quavering voices and sobs from those who went forward at the invitation to confess their sins and to accept Christ. There was the solemn recitation of prayer, and the earnest “amen” at each prayer’s end: “This I ask in the name of Jesus Christ, our savior, and amen.”

The language of the King James Bible was itself a kind of music. The poet, W.H. Auden called poetry “memorable speech.” The King James Bible offers so many examples. Take, for interest, Ruth’s devotion to her mother-in-law, Namoi, as expressed in the Book of Ruth, 1:16: “And Ruth said, Intreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge. . . .” Or this: “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin. . . .” Or, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.”

When I was young, I loved recitation: Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” Often, I didn’t fully know the meaning of what I recited, but I fell in love with the sound of it. I fell in love with the music language can make.

In some way, I suppose, I was already training for the life of a writer. For me, that life became one of telling stories, but at the same time I’ve spent years paying attention to the structure of sentences that can lift off the page and become “memorable speech.” I have sentences from other writers’ books that I often find myself reciting. They move me with their beauty and grace. A few such lines from Kathleen Finneran’s haunting memoir, The Tender Land, will always be with me. The story of her teenage brother’s suicide, the book ends with these lines of direct address:

Sean, time passes, it’s true. Hours, days, and decades. And grief goes by its own measure. Now, before this day of angels ends again, before the sky changes color and the moon follows in its phase from full to new, I want to call out your name and tell you, across the tender land, that we have gone on living. We are all, every one of us, alive.

I could go on and on about how this passage achieves its effect. I could talk about the artful use of pauses (caesuras of a sort) within the long sentence that gathers steam as it charges ahead, the commas barely holding it back until it breaks into the urgent desire of the speaker to call out her brother’s name. I could talk about the effect of the final sentence that follows the rush of the penultimate sentence with a blunt brevity that emphasizes the family’s hard-won survival on the other side of tragedy. I could talk about the way the final word, “alive,” receives extra emphasis because of the pause that “every one of us” provides. The end of this sentence, and the end of this passage, and the end of this book resonates because a writer paid close attention to the sound her words were making on the page. May we all, every one of us—no matter what the sounds of our childhoods may have been—may we understand the poetry that carefully constructed prose can make. May we write the sort of sentences that readers will commit to memory so they can recite them whenever the desire compels them.

The post Music on the Page appeared first on Lee Martin.

April 11, 2022

Now There’s Something You Don’t See Every Day

My apologies for being late with my post this morning. Cathy and I drove back from South Carolina yesterday after attending her granddaughter’s wedding. Somewhere in North Carolina or Virginia (the miles blur for me), we were in stop-and-go traffic because of a wreck ahead of us. We were creeping along when we heard something that sounded like a hound dog baying.

My apologies for being late with my post this morning. Cathy and I drove back from South Carolina yesterday after attending her granddaughter’s wedding. Somewhere in North Carolina or Virginia (the miles blur for me), we were in stop-and-go traffic because of a wreck ahead of us. We were creeping along when we heard something that sounded like a hound dog baying.

“What the heck was that?” Cathy asked just as a car eased up beside us on our right, and we saw the driver playing a trombone. That’s right. I said a trombone. The driver was playing a slide trombone.

Such quirky sights are all around us. All we have to do is take note. Quirks can pay off big time in our writing because details like a man playing a trombone while driving are out of the ordinary, and therefore, remarkable. On the old animated TV show, The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends, there was a segment that featured two elderly gents, Chauncey and Edgar, who’d comment on oddities they observed. “There’s something you don’t see every day, Chauncey,” Edgar would say, and Chauncey would respond, “What’s that, Edgar?” Edgar’s response would contain the punchline.

Writing can make good use of the “there’s something you don’t see every day” moments, but there’s a risk in relying on the strange and odd. The quirky must be within the range of possibility. In other words, the odd things people might do have to be believable and they have to be grounded in character. The wild and the unfamiliar can’t just be anomalous. They have to be organic to the character, and they have to reveal something about that character that may have been submerged until the pressures of the plot brought the odd to the surface in a way that made the strange seem familiar. Everything should be in the service of characterization.

Also on our trip, we went through a town in southern Ohio where it seemed like previously-thought defunct fast food chains appeared to be flourishing. It was as if we’d stepped back to a time when restaurants like Rax and Village Inn Pizza thrived. What an interesting setting that would make for a piece of fiction, particularly if it connected to the stories of its main characters. What would happen if they were taken out of their town? What would happen if a stranger came to visit? How would the main characters be changed forever?

So much of writing is a matter of making the familiar seem slightly strange and letting that strangeness return us to the familiar but with a different way of looking at what previously seemed ordinary. I don’t know about you, but I’m already thinking about that trombone player and what brought him to be playing his horn in traffic on I-77 as well as what that playing might mean for the rest of his life.

Which brings me to this invitation. Give your main character a quirky but believable action. Use it to start a narrative or to close one. Because my guy was playing his trombone while driving north on I-77, (fill in the blank with what it caused). Or construct a plot that puts pressure on my guy until his picks up that trombone and plays. Maybe he’s escaping someone or something. Maybe he’s in mourning. Maybe he’s feeling an irrepressible joy. The possibilities are endless. Let your imaginations meet the quirky things you observe.

The post Now There’s Something You Don’t See Every Day appeared first on Lee Martin.

April 4, 2022

The Softer It Falls

Yesterday, Cathy and I invited our friends, Sheila and Gerry, to attend a cooking class at the Glass Rooster Cannery, where we prepared a Greek feast of falafel, spanakopita, hummus, tzatziki sauce, and baklava. Our instructor, Jeannie, offered tips as we cooked—how to cut an onion if you wanted your slice to retain its shape, how to fold your phyllo dough so the thin layers would have integrity rather than mushing together. She was a helpful presence who gave us permission to create according to our taste. “There’s nothing wrong here,” she often said. “It’s all about you and what you want.”

Yesterday, Cathy and I invited our friends, Sheila and Gerry, to attend a cooking class at the Glass Rooster Cannery, where we prepared a Greek feast of falafel, spanakopita, hummus, tzatziki sauce, and baklava. Our instructor, Jeannie, offered tips as we cooked—how to cut an onion if you wanted your slice to retain its shape, how to fold your phyllo dough so the thin layers would have integrity rather than mushing together. She was a helpful presence who gave us permission to create according to our taste. “There’s nothing wrong here,” she often said. “It’s all about you and what you want.”

What a wonderful example of a teacher. It was obvious that Jeannie knew more about this than any of us, but she wore her knowledge lightly and never dictated what we should do. Instead, she made well-timed suggestions. “Maybe a little less oil on the phyllo,” she said to me once, and I was careful to brush more lightly from that point on. Not only did she offer advice, but she also had all our ingredients ready for us at our cooking station, and she cleaned up for us as we went along, so we could concentrate on the assembly of the dishes.

This is what a good writing teacher does—gives students an understanding of the elements they’ll need to practice their craft, stays out of the way and lets students try according to their own aesthetics, is quick to offer advice when things are about to go off the rails, offers a method of correction when necessary. A good teacher never dictates but instead finds a covert way of suggesting what they know to be the truth. A good mentor relationship is one in which the student arrives at understanding rather than having that understanding dictated to them.

One of my students told me last week they often hear my voice when they’re writing. I remember when that used to be the case for me. I had one writing teacher whom I heard each time I sat down to write. Gradually, that voice blended with my own voice, so today the principles he taught me are mine. When I hear a voice saying you can’t get away with this, or you need to do this, or why don’t you walk around that idea to consider it from all angles, I know my mentor’s teaching has become so ingrained in me it seems to have always been mine. At some point, the mentor fades from consciousness, leaving their influence behind them for the writer to use as their journey continues.

Like Jeannie at the Glass Rooster, a good mentor treads lightly but with great impact, passing along all they’ve learned, leaving it to the students to accept or reject and maybe somewhere in the future to pass along to someone else. “Advice is like snow,” Samuel Taylor Coleridge said. “The softer it falls, the longer it dwells upon, and the deeper it sinks into the mind.” We’re all learners in this writing game. A good writing teacher doesn’t try to create another writer like them but instead offers everything they know that will help that writer become the writer only they can be.

The post The Softer It Falls appeared first on Lee Martin.

March 28, 2022

A Whisper in the Dark: A Writer’s Voice

It’s a raw day here in central Ohio with a brisk wind, temps in the thirties, and a few snow pellets from time to time. Wouldn’t you know the forsythia and daffodils are in bloom? It seems to happen each spring. A stretch of warm days coaxes the plants to light and air. They put on their blooms only to get hit with a cold snap. Our spirits rise only to get tamped down. We long for consistent warmth, the kind that will make winter a distant memory.

It’s a raw day here in central Ohio with a brisk wind, temps in the thirties, and a few snow pellets from time to time. Wouldn’t you know the forsythia and daffodils are in bloom? It seems to happen each spring. A stretch of warm days coaxes the plants to light and air. They put on their blooms only to get hit with a cold snap. Our spirits rise only to get tamped down. We long for consistent warmth, the kind that will make winter a distant memory.

A writing life is a life of peaks and valleys. Sometimes we’re up, and sometimes we’re down. That never changes no matter how much you publish or how much acclaim you receive. The fallow periods come, and we despair. Is this it, we ask ourselves. Is this the beginning of the end? Is this the day I stop being a writer?

To my way of thinking, only we can make the decision to stop. It’s easy to believe that other people—the gatekeepers like agents, editors, contest judges, etc.—hold that power, and to an extent they do because they can always say no to us. The last time I checked, though, no agent, editor, or contest judge ever sat with me in my writing room while I worked. If they threaten to invade that sacred space via their naysaying voices from past experiences, I find a way to say no to them. No, you may not steal the joy I feel when I’m writing. No, you may not cause me to cast doubt on myself. No, you may not make me hesitant. Our writing spaces are where we can be bold, ferocious, insistent. They’re spaces in which we can practice what we love.

And yet how many times over the years have I told myself to just stop—to stop trying to figure out narrative arcs, to stop exploring characters, to stop wrestling with sentences. How many hours have I spent alone in a room imagining stories or recreating experiences? How many hours have I stolen from loved ones? How many hours have I stolen from myself? Then I realize it’s the only thing I know to do—to keep trying to give this world of contradictions and chaos some sort of artistic shape, to make it hold still for a moment, so I’ll have a chance at clarity and hope. Without that, I fear I might vanish, caught up in the chaos. I might fall into such a well of despair I’ll never find my way back to solid ground.

I write to better understand our conflicted hearts. I write to remember the humanity we share. I write to bear witness. I write to illuminate. As pretentious as it may sound, I write to try to stop myself from disappearing. For that reason alone, I imagine I’ll keep doing what I do as long as I’m able even if no one’s interested in what I write. Maybe I’ll just be whispering in the dark, but a whisper is something I can hear. A voice, no matter how quiet, is still a force. It says, “Listen.” It says, “I matter.” It says, “We’re not alone.” Each time I sit down to write, I speak from the chaos. With ink marks on a page, I engage with the world, and why would I ever want to stop doing that?

The post A Whisper in the Dark: A Writer’s Voice appeared first on Lee Martin.

March 21, 2022

The Saga of the Smart Bulbs: A Resolution

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you may remember that for the last couple of weeks I’ve been trying to get my smart bulbs to work. I’ve accused them of not being very smart at all, I’ve said there’s always a workaround, and I’ve said sometimes it’s okay to give up. Today, I’m here to report that I finally figured out how to get them to work. I won’t bore you with the details. Suffice it to say our outdoor lights now come on at sunset and go off at sunrise without us having to flip a single switch. The saga of the smart bulbs has reached its resolution, and there’s really nothing more I can say about that.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you may remember that for the last couple of weeks I’ve been trying to get my smart bulbs to work. I’ve accused them of not being very smart at all, I’ve said there’s always a workaround, and I’ve said sometimes it’s okay to give up. Today, I’m here to report that I finally figured out how to get them to work. I won’t bore you with the details. Suffice it to say our outdoor lights now come on at sunset and go off at sunrise without us having to flip a single switch. The saga of the smart bulbs has reached its resolution, and there’s really nothing more I can say about that.

So let me talk about writing instead. In every narrative there comes a point where there’s nothing more that can be said. Every bit of the premise has performed its function. Every detail has been accounted for. Each main character has reached the end of their arc. At that point, there’s nothing for the writer to do except gracefully exit the stage. “Every trail has its end,” James Fennimore Cooper writes in The Last of the Mohicans, “and every calamity brings its lesson.” When we write a narrative, we move forward to a landing place where a world, meticulously constructed, will never be the same. Along the way, we follow the narrative arcs the characters themselves have created. Those arcs lead to moments of change, or refusals to change, which are moments beyond which a character’s life will never be the same. The possible life, the one someone might have had, recedes, leaving its shadow, and the readers feel its simultaneous absence and presence. “I was trying to feel some kind of good-bye,” Holden Caulfield says in J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. “I mean I’ve left schools and places I didn’t even know I was leaving them. I hate that. I don’t care if it’s a sad good-bye or a bad good-bye, but when I leave a place I like to know I’m leaving it. If you don’t you feel even worse.” Indeed. As readers, we like to know our characters’ worlds are irrevocably altered by the end of the narrative. A choice made, a word said, or a choice not made, or a word not said, brings us to the end. Something set in motion in the opening has its completion and its resonance.

Sometimes it takes finding the end of a narrative to truly understand its beginning. For that reason, I suggest always writing through to the end of a first draft. Keep going even when the writing seems like slogging through mud. The writing itself will teach you something about the tale you’re telling. Remember that illumination is always a part of resolution. Something ends, and, if only for a moment, we see more clearly. It may take countless drafts, but once you’ve understood the narrative arc—once you know where it ends—you can go back to the beginning and add or enhance the first details from which your ending grows. Those first words on the page? They’re always the beginning of the end.

The post The Saga of the Smart Bulbs: A Resolution appeared first on Lee Martin.

March 14, 2022

Sometimes It’s Okay to Give Up

For those of you following the saga of the smart bulbs, Cathy and I ended up buying an Echo Dot, and last night we were able to get it to recognize and control two of our bulbs, but not the other two. This afternoon, after a visit to Best Buy and some internet research, I was able to get Alexa to recognize the other two bulbs, but I’m not sure she was able to connect them to our network. We’ll find out this evening when we have the bulbs scheduled to come on.

For those of you following the saga of the smart bulbs, Cathy and I ended up buying an Echo Dot, and last night we were able to get it to recognize and control two of our bulbs, but not the other two. This afternoon, after a visit to Best Buy and some internet research, I was able to get Alexa to recognize the other two bulbs, but I’m not sure she was able to connect them to our network. We’ll find out this evening when we have the bulbs scheduled to come on.

All of this is to say, we’ve expended a lot of time and energy with these bulbs, and we’re still not sure we’ve succeeded. Such is the way of writing so much of the time. Day in and day out, we labor. Sometimes we feel we’re doing well, and sometimes it’s as if we’re chiseling into stone, a laborious process that we hope will yield results.

As unyielding as the process may be, there’s always hope with each piece we attempt that the journey will take us where we’re meant to be. But what if it never does? I’m here to tell you that sometimes it’s not only permissible, but also the smart choice, to give up. File that story or essay or novel or poem away and maybe return to it somewhere down the road. I have more than a few novels that will never see the light of day as well as some stories and essays. I don’t consider them failures. I think of them as what I had to write so I could write the next thing. No writing is without its merit because all writing deepens our understanding of craft. It can even open material we didn’t know we had. For instance, I have a novel that never got published, and it’s a good thing it didn’t. That book had the germ for the novel that did get published, The Bright Forever, that ended up being finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. If I’d published the first manuscript, I likely wouldn’t have written The Bright Forever. I wasn’t quite ready to write that book. Sometimes we must live with our material a while before trying to give shape to it on the page.

We’ll see about these smart bulbs just as we’ll see about all the projects we attempt. We’ll hope for illumination, but if it doesn’t come, we’ll glean the things that did work in the writing and turn them into gold in other things we write. We should never judge ourselves based on any single thing we attempt to write. A writer’s journey is more than just a single book or essay or story or poem. A writer’s career is a life-long apprenticeship. Each thing we try to write teaches us something, and we’d be smart to never forget that.

And now just for fun, as I enter my spring break week, here’s something I posted on FB nine years ago today:

Please listen closely as my options have changed:

If you’d like to publish my story collection, press 1.

If you’d like to publish my novel, press 2.

If you’d like to give me a contract based on a few pages of another novel, press 3.

If you’d like to have these options repeated, please stand on one leg and cluck like a chicken. Someone will be with you shortly.

The post Sometimes It’s Okay to Give Up appeared first on Lee Martin.

March 7, 2022

My Smart Bulbs Are Morons

Cathy and I both work from home, which makes a reliable internet connection crucial. A while back, we’d been having some issues, so we called our internet provider who installed a new modem and router that put us on a 5G network. When our smart bulbs started having problems, we. . .well, let’s just say we went through the frustrations that led to the title of this post. Our smart bulbs just weren’t that smart anymore because, as we learned, they need a 2.4G band to operate properly. When we talked to our internet provided, we learned that our new modem/router combines the two bands. In other words, the 2.4 is still there, but the default is the 5. The suggested workaround is to put a towel over the router to impede the range of the 5G, thereby separating it from the 2.4 long enough to reset the bulbs and make them smart again. We’re in the process of trying this. Cathy is taking the bulbs for a ride as I type this, giving them the distance they need to forget they were ever trying to connect to the 5G band. If anyone’s interested, I’ll keep you posted.

On our farm, when I was young, my father was expert with the workaround: a pipe slipped over the handle of a wrench to give the leverage needed to loosen a cranky nut, rags stuffed in the bed of the pickup truck to keep grain from leaking, oil applied to a saw blade to making the cutting easy—all the little tricks to make things work the way they should. I’d be ready to give up, and he’d say, “Nah, there’s always a way.”

And so it is with our writing. The thing that doesn’t work can always work. Sometimes, as with these smart bulbs, it takes a distance, enough distance for us to forget our original intentions so the story, essay, poem, novel, etc. can reconfigure itself. We may think we know where something is heading on the page, when really we don’t know at all. I always say the thing being written is always smarter than we are. It’s just waiting for us to catch up to it. That can take time. We must be patient. Often, if we turn our attention to something new, the unconscious parts of our minds will be working over a problem with the old piece and will eventually present us with a solution. A light bulb, we might say, will turn on and illuminate the shadowy parts of the piece that haven’t been fully lit.

Nothing is as sweet for a writer as a moment of discovery—that moment when the writer fully knows what the piece has known all along. We can try intellectualizing a solution to a writing problem, and sometimes that works. We can switch the point of view, we can occupy a different perspective, but sometimes it’s a matter of forgetting and letting the piece find you.

The post My Smart Bulbs Are Morons appeared first on Lee Martin.

February 28, 2022

Memoir and the Imagination

My wife Cathy has told me it’s all right if I tell this story. It’s her story of never knowing, until recently, the identity of her biological father. Her mother, a few years before she died, finally, when pressed, gave Cathy the identity of her father. He was deceased, but Cathy had no reason to doubt her mother was telling her the truth. Cathy could recall her mother being in this man’s car when they had an accident during Cathy’s childhood, so it wasn’t too much of a stretch to imagine that the two of them had a relationship.

My wife Cathy has told me it’s all right if I tell this story. It’s her story of never knowing, until recently, the identity of her biological father. Her mother, a few years before she died, finally, when pressed, gave Cathy the identity of her father. He was deceased, but Cathy had no reason to doubt her mother was telling her the truth. Cathy could recall her mother being in this man’s car when they had an accident during Cathy’s childhood, so it wasn’t too much of a stretch to imagine that the two of them had a relationship.

Fast forward to these days of DNA tests, and to make a long story short, Cathy found out, through DNA matches, that her mother hadn’t told her the truth. Her actual biological father, it turns out, was a man who had a wife and a family of his own. He carried on an affair with Cathy’s mother for the time it took to have at least three of his children. She gave two of those children up for adoption. Cathy was the one she kept.

Her mother carried her secret with her to the grave, but DNA has now revealed the facts she couldn’t bring herself to admit. Cathy has been reunited with two full-blooded sisters. As an only child, I can only imagine what this must be like for her and her sisters. They went so long without knowing the truth, and now they stand united in the bonds of love they feel for one another. They’ve finally found their way back together despite the deeds of others that separated them. I often think of the miracle of it all. Sometimes Cathy’s phone rings, and when she sees who it is, she says, “It’s my sister.” I can tell how much joy it brings her to say that word. How often, I wonder, did she try to imagine her father into existence? How often did she wonder whether it might be him, or him, or him? The mystery of what we don’t know can lead us to wonder, to ponder, to dream.

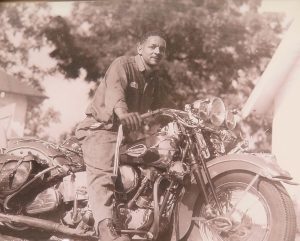

So it is for the writer, particularly those of us who tell family stories in our memoirs and personal essays. When it comes to family, there’s always something we don’t know—the origin story of our parents’ relationship, for instance. We might know the facts—where they met, etc.—but how often do we know what they carried in their hearts and minds? How often do we know the interior lives they lived? For instance, what was it like for Cathy’s mother, a white woman in a small Midwestern town, to carry on a long-term affair with a married Black man during the late 1950s and early 1960s? How much did she love him? What did it cost her to try to maintain that love? What did she feel inside, knowing most nights he was with his wife and children? Did it practically break her when she made the choice to give up two children and when ultimately the affair came to an end?

My own parents married later than what was usual. My mother was 41, my father was 38. I imagine they’d all but given up on finding love. I know my father used to stay late at my grandparents’ general store where my mother worked after teaching school during the day, but that’s all I know about their coming together. I can’t keep myself, though, from imagining what my father’s proposal must have been like and whether it took place one of those nights after the store was closed. In one of my essays, I say, “I like to imagine the melancholy call of rain birds, a breeze moving through the branches of the oak trees, the lush white pom-pom blossoms of a snowball bush, and my mother memorizing all this so she could recall it time and time again before she finally said, ‘I’m in love with Roy Martin.’”

If you admit to your readers that you’re using your imagination, you can rely on the intersection between what you know and what you wish you knew to create a situation and an interior life. You can daydream on the page, and in that daydream, you’ll not only be making your family members more vivid, you’ll also be revealing more of your own character because you’ll be the one making the choices, and those choices will expose your heart in a way you might be reluctant to without the safety of the imagination.

Cathy’s biological father has been dead for many years. She still has much she doesn’t know, but at least now she has two sisters with whom to make that journey into the past and on through the present into the future.

The post Memoir and the Imagination appeared first on Lee Martin.

February 21, 2022

Interrogating Memory

From 1963 through 1969, my parents and I lived in Oak Forest, Illinois, a southern suburb of Chicago. We’d come there from our farm in southeastern Illinois so my mother could teach the third grade in the Arbor Park School District, #145. As many of you who have read my memoirs know, my mother had lost her teaching position downstate, and her search for another brought us to Oak Forest. At the time, its population was around four thousand people. Oak Forest was a village, but after living in a rural area and attending a two-room country school, I thought that village was huge. I came to love the life we had there and was sad to move back downstate when my mother retired just as I graduated from the eighth grade and made ready to enter high school. It wasn’t a surprise to me, though, that my parents decided to go back home because all the while we lived in Oak Forest, we escaped it whenever we could. We sublet our apartment and spent the summers on our farm. We spent the Christmas holidays there as well and weekends whenever we could. Friday afternoons often found us in the car making the five-hour drive south.

From 1963 through 1969, my parents and I lived in Oak Forest, Illinois, a southern suburb of Chicago. We’d come there from our farm in southeastern Illinois so my mother could teach the third grade in the Arbor Park School District, #145. As many of you who have read my memoirs know, my mother had lost her teaching position downstate, and her search for another brought us to Oak Forest. At the time, its population was around four thousand people. Oak Forest was a village, but after living in a rural area and attending a two-room country school, I thought that village was huge. I came to love the life we had there and was sad to move back downstate when my mother retired just as I graduated from the eighth grade and made ready to enter high school. It wasn’t a surprise to me, though, that my parents decided to go back home because all the while we lived in Oak Forest, we escaped it whenever we could. We sublet our apartment and spent the summers on our farm. We spent the Christmas holidays there as well and weekends whenever we could. Friday afternoons often found us in the car making the five-hour drive south.

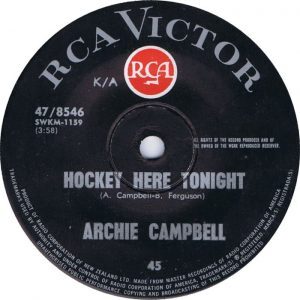

It was at the end of one of those drives that I experienced something that has stayed in my memory for years. We were tired and hungry when we finally made the turn from the St. Marie Road onto Route 50. We were close to our farm but not quite there, and my father suggested we pull into Art’s Truck Stop for some hamburgers. A juke box was playing a comedy recording featuring a yokel who was telling the story of coming upon a sign outside a building that read, “Hockey Here Tonight.” This yokel, intrigued, buys a ticket and for the first time in his life experiences a hockey game. My father laughed along with the man’s description of what he observed on that “frozen pond” where a smarty man in a striped shirt dropped a hard, round, black thing, and men with runners on their shoes and sticks in their hands tried to knock that hard, round, black thing into a basket that was guarded by its “owner” who didn’t want that thing in his basket. There was a basket and its owner on either end of the frozen pond, and neither seemed to be too amenable to having that hard, round, black thing in its basket. “What is that thing?” the yokel asked the man sitting next to him. “Why, that’s hockey,” the man said.

I’d been watching the Chicago Blackhawks on WGN television, so I was familiar with the game, but I couldn’t figure out why the comedy recording, outside the yokel’s naive description of the sport, was supposed to be funny. My father explained that hockey was a word some folks used instead of the crasser words, “poop,” or “shit.” Aha, a euphemism for good old number 2. No wonder the men with the sticks were trying to clear it from the frozen pond so they could get on with doing whatever it was they had come to do.

Ever since that night, I’ve thought the artist of that comedy recording was Andy Griffith—that is until today when I looked it up on YouTube and discovered that my memory has been faulty all these years. The artist of “Hockey Here Tonight” is Archie Campbell, who would later be a regular on the cornpone comedy TV show, “Hee Haw.”

I tell this story to illustrate a point for those of us who write memoir. We should be on the lookout for opportunities to interrogate memory. Tobias Wolff, at the beginning of his memoir, This Boy’s Life, says, “. . .this is a book of memory, and memory has its own story to tell.” Indeed. If we ask the right questions when we recall our experiences, we can speculate on what the ordinary details of our lives—a comedy record playing on a jukebox, for instance—have to show us about the truth of our living. The question for me, then, is not one of whether Andy Griffith or Archie Campbell recorded “Hockey Here Tonight,” but instead one of why I chose for years and years to remember Andy Griffith’s voice coming from the jukebox that night at the truck stop. Already, I have my answer to that question. It has something to do with the fact that I knew Andy Griffith from his television show where he played Sheriff Andy Taylor. Andy Taylor was the perfect father while my father wasn’t. Often driven by temper, my father, that night, was at ease and laughing. My mother was laughing, too. We were, for those few moments, blessed, and maybe that’s why I chose for all these years to think Andy Griffith was with us in that truck stop, his gentle humor showing us how our lives, if we chose, might be.

The post Interrogating Memory appeared first on Lee Martin.

February 14, 2022

To My Wife on Valentine’s Day

This is what I remember. It’s 1974, and we’re sitting in my Plymouth Duster in your driveway at the end of our date. I’ve got the Rolling Stones playing on my tape deck. It’s still early spring, and the night air is cool. Our breath is causing my car windows to fog up with condensation. Your house is dark, but the porch light burns above the front steps. The air has that earthy smell of wet grass and mud, and the Stones are singing “Let’s Spend the Night Together.”

This is what I remember. It’s 1974, and we’re sitting in my Plymouth Duster in your driveway at the end of our date. I’ve got the Rolling Stones playing on my tape deck. It’s still early spring, and the night air is cool. Our breath is causing my car windows to fog up with condensation. Your house is dark, but the porch light burns above the front steps. The air has that earthy smell of wet grass and mud, and the Stones are singing “Let’s Spend the Night Together.”

We’ve been to the bowling alley, or the theater, or maybe we’ve just been for a drive with a stop at Veterans’ Point in Red Hills State Park. We’ve been coming to Veterans’ Point at the end of each date since our first one. This is our place. We’ve gone from our single first kiss to a bevy of kisses, some of them sweet and tender, and some of them more passionate. We’ve kissed with music playing on my tape deck. We’ve kissed to the love ballads of Bread, Cat Stevens, Jim Croce, and we’ve kissed to the driving, sensual beat of Deep Purple, Black Oak Arkansas, and the Stones. We’ve kissed and kissed and kissed, and we’ve pressed our bodies together, hidden in the dark.

But now we’re in your driveway, and the Stones are playing and Mick Jagger is singing, promising us, “We could have fun just groovin’ around, around, and around, and oh, my, my.”

I imagine we’re both aware, without directly saying as much, that we know what groovin’ around is really referring to, and then you lay your hand on my thigh and lean close to sing into my ear, “Let’s spend the night together, now I need you more than ever,” and I feel what I’ll call a stirring, and I’ll admit I’m a little shaken because this is the first time a girl has been this bold with me—can you really be thinking about groovin’ in the way we know Mick Jagger means for us to think?

The smell of earth is all around us. The damp night is all around us. The bass of my tape deck is thumping and vibrating. The car windows are steaming over more and more as our breathing quickens.

Then the porch light flicks on and off several times.

“My mother,” you say, as you slide toward the passenger side door. Does one of us say, I love you, and does the other one answer, I love you, too? I only remember watching you step out of the car. “Call me,” you say, and I tell you I will. Then I watch you walk to your front door. I watch the sway of your hips. You’re beautiful as you step from the shadows into the glow from the porch light. Remembering it now, I see you stop, one hand holding open the screen door, while you turn to take a last look at me, a coy turn to your lips as if you know exactly what’s about to come.

The post To My Wife on Valentine’s Day appeared first on Lee Martin.