Lee Martin's Blog, page 13

June 19, 2023

The Shapes of Things: Letting Content Determine Form

When I worked with my father on our farm, I often found myself frustrated with a task I couldn’t perform—a rusted nut that couldn’t be turned, a grease zerk that was hard to reach, a saw blade that kept catching. When I’d say I couldn’t do something, my father would say, “Can’t never did nothing.” Then, he’d set about coming up with a workaround. A pipe slipped over a wrench handle to give us more leverage, a flexible hose for the grease gun to ease our way to that tricky zerk, motor oil poured over the saw blade to keep it from sticking. Farming was my father’s passion. He always saw a way to accomplish a chore. If one effort wouldn’t do the trick, he found a way to modify his method.

When I worked with my father on our farm, I often found myself frustrated with a task I couldn’t perform—a rusted nut that couldn’t be turned, a grease zerk that was hard to reach, a saw blade that kept catching. When I’d say I couldn’t do something, my father would say, “Can’t never did nothing.” Then, he’d set about coming up with a workaround. A pipe slipped over a wrench handle to give us more leverage, a flexible hose for the grease gun to ease our way to that tricky zerk, motor oil poured over the saw blade to keep it from sticking. Farming was my father’s passion. He always saw a way to accomplish a chore. If one effort wouldn’t do the trick, he found a way to modify his method.

I often tell the story of how I wrote two hundred pages of my novel, The Bright Forever, before I realized what it was about the story that really interested me. I wasn’t so much interested in the crime at the heart of that novel as I was its effects on various populations in my fictional Indiana small town. I tossed those two hundred pages and started over. “Dude, are you okay?” a concerned high school student in Nebraska asked me when I told that story. I doubt that he could imagine ever writing two hundred pages, and to throw them away? To his way of thinking, I must have been mad. I told him that was the best day because that was the day I finally knew why I was writing that novel.

So it is with everything we write. The question of how to shape something comes from the reason you’re writing it. What is it about the material that matters deeply to you? What are you trying to explore? What mystifies you? What are you curious about? What shape best allows the full exploration of the beating heart of your work? Sometimes we have to write a lot of pages before we know the answers to these questions. At some point, though, our intentions become clear to us. At that point, we can re-evaluate our form to see whether a modification might better allow the full expression of what we’ve come to the page to do. To my way of thinking, content always dictates form. Sometimes, though, we have to live with what we’ve first set down so we can better know it. Once we know why we’re writing what we’re writing, we can better know the shape it has to take.

I remember all the trials and errors my father and I went through to accomplish a task. If one workaround proved to be ineffective, my father thought of another one. We were as far apart as a father and son could be when it came to our interests, but eventually the writer I became would understand we shared a faith that if we worked long enough and hard enough, we’d get where we wanted to go. Such is the case with rusted nuts, stubborn zerks, and cantankerous sawblades. Sooner or later, the nut turns, the zerk gets greased, the sawblade glides. And such is the case for our writing. Sooner or later, the content yields the form. We know where we are in the material and why we’re there. The writing is easier after that.

The post The Shapes of Things: Letting Content Determine Form appeared first on Lee Martin.

June 12, 2023

Taking the Temperature of Writers’ Conferences

I just returned from teaching at the West Virginia Writers’ Conference, so I’ve decided to rerun this old post.

I just returned from teaching at the West Virginia Writers’ Conference, so I’ve decided to rerun this old post.

If you’re of a certain age, you’ll remember the old thermometers, the ones that you had to keep under your tongue for four minutes, the ones you had to shake down with an expert snap of the wrist, the ones that made you squint in order to make out the level of the mercury that told you your temperature. Believe it or not, I’m now the owner of a thermometer very much like this, only this one contains Galinstan, “a non-toxic, Earth friendly substitute for mercury.” You still have to hold it under your tongue for four minutes.

I was surprised to find out how impatient I was for those four minutes to pass, accustomed to the quick turnaround of a digital thermometer. I’d been lured into the world of instant gratification. Shame on me. If there’s one thing being a writer teaches me, it’s the art of patience. Results come in increments; sometimes, many more than four minutes pass between them. A career happens over a lifetime and not in a few seconds.

When I was just starting out, I decided to attend some writers’ conferences. It turned out to be a smart thing for me to do. Now, as I teach in conferences each year, I try to keep in mind the person I was when I was a participant. I try to remember that I was nervous and just a little scared to have my work talked about by published writers and the other participants in the workshop. I try to remember that I often felt very far from home, a little bit like the boy on his first day of school. I was lucky, though. The writers’ conferences I attended gave me exactly what I needed:

A supportive group of folks who took my work seriously. In their company, I felt like a writer.A smart group of folks who told the truth, but as delicately as they could.Exposure to the literary life, and contact with agents and editors.A network of friends, many of whom I’m still in touch with today.Dedicated workshop leaders who were more interested in teaching than in playing the role of “famous author.”The sense that with hard work and continued practice I could be better.Maybe, as I’ve taken the temperature of writers’ conferences (groan), I’ve given you something to think about. If you decide to attend one, stay open to learning, check your egos at the door, get to know people, give the sort of effort and respect to others that you want for yourself, leave with a sense of purpose and a direction to follow with your work. When I teach, my one objective is to enter a participant’s work with thanksgiving for its gift, with an understanding of what the work is trying to do, with plenty of praise for what’s working well, and with some suggestions for continued work. I hope I’m successful in returning each participant to his or her writing space with renewed vigor and a genuine excitement about the work that lies ahead.

The post Taking the Temperature of Writers’ Conferences appeared first on Lee Martin.

June 5, 2023

At the End

One of my readers recently posed a question about loose ends in a book-length narrative and how to know what needs to be resolved and what can be left slightly open. The question also included an inquiry into the effectiveness of epilogues.

One of my readers recently posed a question about loose ends in a book-length narrative and how to know what needs to be resolved and what can be left slightly open. The question also included an inquiry into the effectiveness of epilogues.

A book-length narrative asks us to invest in the sweep of the main characters’ lives. A writer sets into motion a narrative arc, and as readers we have a right to expect by book’s end some sort of resolution. A question posed gets answered. Will Gatsby reclaim his long-ago love, Daisy? Will Atticus Finch successfully defend the wrongly accused Tom Robinson? Will Romeo and Juliet find their happy-ever-after? The resolution of a sequence of dramatized events, though, is different from the resolution of our characters’ lives. Gatsby dies by murder. The jury convicts Tom Robinson, which leads to his death, and to the danger inflicted upon Atticus’s children at the very end of the book. Romeo and Juliet? Well, I think we all know what became of them. Our main characters who survive the circumstances of their lives move on into their futures beyond the ends of their narratives. Nick Carraway, disillusioned, returns to his native Midwest. Atticus Finch watches over his injured son, Jem. The narrative arc has reached its end, but there’s a door that opens into the future, and we imagine how the characters’ lives will be affected by what they’ve lived through. The final sentence of To Kill a Mockingbird resonates with the future while keeping a foot solidly in the dramatic present. The injured Jem is asleep in his bedroom and Atticus stands watch over his son. Our narrator, Jem’s sister Scout, closes out the narrative with this final passage:

He [Atticus] turned out the light and went into Jem’s room. He would be there all night, and he would be there when Jem waked up in the morning.

The events of the central drama have come to an end, but so much awaits Jem and Scout and Atticus once the morning comes, and the morning after that, and the one after that, and on and on through their lives which have been forever altered by their experiences in this small southern town. Those future lives are in flux and best left to the reader’s imagination. It can be quite effective, then, to close the central dramatic arc of a book while leaving the future for the main characters slightly open.

I don’t have any strong feelings about epilogues, but I see their effectiveness when wishing to dramatize characters’ lives at a time far in the future from the central dramatic arc of the book. Still, I should note that a skilled writer can allude to distant futures with succinct statements. Scout, for instance, walks the enigmatic Boo Radley back to his house: His fingers found the front doorknob. He gently released my hand, opened the door, went inside, and shut the door behind him. I never saw him again. Just like that, the story of Boo Radley ends. I should also note that the end of a book, whether during the main narrative or in an epilogue, can be an opportunity to emphasize some of the major moments of the story. Here, again, is Scout, speaking of Boo Radley: He gave us two soap dolls, a broken watch and chain, a pair of good-luck pennies, and our lives. With this, Scout sweeps us back through the narrative. She even manages to recall her friend Dill and her neighbors Miss Stephanie Crawford, Miss Maudie, and Mrs. Dubose. She reminds us of Jem and her coming home from school and racing each other to reach their father. She imagines events such as Atticus’s shooting of the rabid dog from the perspective of Boo Radley, and as she does, she evokes the narrative we’ve lived through.

In short, the power of a book-length narrative comes from a certain degree of closure to the central dramatic events while leaving the consequences to reverberate in the silence that comes upon us after we read the final page. We sense our main characters’ lives going on without us there to witness them, and the bittersweet feeling we have when we say goodbye to loved ones fills us. On one hand, we’re satisfied to have shared the drama of the narrative with these people, but on the other hand, we’re sad to have to let them go.

The post At the End appeared first on Lee Martin.

May 29, 2023

This Place of Dirt and Dust

The peonies are in bloom. Each year, in time for Memorial Day, these fragrant flowers make their showy appearance. When I was a child, my mother made bouquets. She put a handful of gravel in the bottom of a coffee can wrapped in aluminum foil. She added the cut peonies and maybe a few irises if they happened to still be in bloom. She poured in water, and we set out for the cemeteries to tend to the family graves. Up until 1971, Memorial Day was known as Decoration Day, a day set aside for remembrance.

The peonies are in bloom. Each year, in time for Memorial Day, these fragrant flowers make their showy appearance. When I was a child, my mother made bouquets. She put a handful of gravel in the bottom of a coffee can wrapped in aluminum foil. She added the cut peonies and maybe a few irises if they happened to still be in bloom. She poured in water, and we set out for the cemeteries to tend to the family graves. Up until 1971, Memorial Day was known as Decoration Day, a day set aside for remembrance.

These days, I live some distance from my native southeastern Illinois, so at times like these I must rely on my memory of Decoration Days gone by. My parents and I lived on a farm in Lukin Township on the Lawrence County side of the gravel road that divided it from Richland County. I sat in the back seat of my father’s Chevrolet Bel Air, coffee cans full of flowers on the floorboards at my feet while we drove the county line. Our Bel Air was redolent with the scent of peonies—pink and white and red. Gravel pinged our fender wells when my father steered too close to the center where a county road grader had left a ridge. Mourning doves and killdeer took wing ahead of our advancing car. The dust rolled out behind us.

I come from this place of dirt and dust. I come from the fields of soybeans and wheat and corn. Barbed wire hooked into my heart at an early age, and even though I eventually moved away, turning my back on a farmer’s life, those barbs never fully let go. If I close my eyes, I can see the milkweed in the fencerows. I can hear the lowing of cattle. I can remember the way the air smells just before rain. I remember my mother’s print cotton dresses, the ones with thin matching belts, and my father’s Dickies work suits in forest green or silver gray twill. I remember the way I helped my mother carry the flowers to the graves at Gilead and Ridgley and Shiloh, how we snugged them up against the headstones. I recognized my two grandmothers’ graves and the graves of the grandfathers I never knew because they died either before or shortly after I was born. I didn’t pay attention when my father and mother talked about other ancestors. They were merely names to me: Henry, John, Mary Ann, Warren, Abigail, Lola, Owen. It would be years before they’d matter to me, years before I’d gather their stories to connect me more fully to my family and this place I’d left.

Today, on what we now call Memorial Day, I’m thinking about all my ancestors, and I’m thinking about those country cemeteries and how sometimes, when you’re there, you can suddenly realize you’re removed from any artificially made sound—no traffic noise, no clamor of machinery, no blast of music, no human voice. Nothing but the call of a crow, the chatter of a squirrel, the wind moving through a field of timothy grass. The timothy moves in waves. It undulates. It whooshes in the wind. Listen. Listen to the whispers of all who came before, telling us to remember them. Once upon a time they were as alive as any of us can ever hope to be.

The post This Place of Dirt and Dust appeared first on Lee Martin.

May 22, 2023

The Shared Experience: Tips for Reading from Your Work

My latest guilty pleasure is watching people on YouTube react to their first time hearing a song. I can’t quite figure out why I love doing this so much, but I suspect it has something to do with the pleasure I get from seeing someone share my experience. When someone feels the emotional impact of a song like “Bridge Over Troubled Water” or “Memory,” it validates my own response, and it gives me hope. In what can often seem like a cruel or unfeeling world, I’ve found a kindred spirit. If there are enough people who are unashamed to be moved by a song, there might just be a chance we can collectively move to an increased level of empathy and love.

My latest guilty pleasure is watching people on YouTube react to their first time hearing a song. I can’t quite figure out why I love doing this so much, but I suspect it has something to do with the pleasure I get from seeing someone share my experience. When someone feels the emotional impact of a song like “Bridge Over Troubled Water” or “Memory,” it validates my own response, and it gives me hope. In what can often seem like a cruel or unfeeling world, I’ve found a kindred spirit. If there are enough people who are unashamed to be moved by a song, there might just be a chance we can collectively move to an increased level of empathy and love.

Last week, I was in my native southeastern Illinois to do an event at the Olney Public Library. On the morning of the event, I stopped by the local radio station to do an interview. I read a very short section of my novel, The Glassmaker’s Wife, and when I was finished the interviewer said, “Could you please read every book on tape that I listen to?” That’s exactly the effect I want for my listeners whenever I read from one of my books. I want to draw them into the world of the book, so they feel what my characters feel. To do that, I first have to feel my characters’ emotions and their complicated lives as I put them on the page. I have to feel, for instance, the love the fifteen-year-old Eveline Deal has for her employer, Betsey Reed, in The Glassmaker’s Wife. When Eveline feels that Betsey has wounded her with a sharp or dismissive word, I have to feel that hurt within my own heart. If we’re writing without feeling, something’s wrong.

When I read from a novel, I keep in mind the fact that the words, even in passages of description or summation, are coming from a world in which my characters feel strong emotions. It’s my job to express those emotions in the writing as well as the reading. At any given point, a character speaks and feels through me. A good reading requires the writer to take their time. No rushing through a scene, no flattening out the tone, no refusal to engage with the characters and their situations. A good reader interprets the work, so the audience members feel as if they’re present in the scenes they’re hearing from the book. Ideally, the audience isn’t just hearing; they’re immersed in the action as it unfolds, and they’re feeling what the characters feel.

Here are some things to keep in mind while reading from your work. Varying the pace of your delivery can be effective. Consider what you want to emphasize in a given sentence or passage. A brief pause before that point of emphasis puts your listeners on alert. They’re about to hear something that matters greatly. A longer pause after you’ve delivered the important point lets it resonate in the silence. Remember to make eye contact with your audience members. That’s a technique for drawing them into the worlds you’re portraying. It’s especially effective if you make eye contact with a particular audience member when delivering a point of emphasis. Choose different audience members during the time of your reading. Your objective is to make as many people as you can feel as if you’re reading only to them. Work on capturing the essence of your characters’ voices without exaggerating them. When reading a scene of dialogue, look toward a distinct part of the audience just before a character speaks. If you look to your left for one character and to your right for another character, your audience will have an easier time following the scene. This is especially important when there are no dialogue tags for the characters—no “he said” or “she said” or “they said.” Finally, remember to vary the inflection of your voice to emphasize emotional shifts in the scene. Knowing when to let your voice soften, for instance, or when to harden, or when to increase in volume, or become pensive or elegiac can take your listeners through a myriad of emotions. Every choice you make while reading from your work should be made to enhance your audience’s listening experience.

When I read at the Olney Public Library, there were people present from so many parts of my life. There were high school classmates, family members, friends, professional colleagues, and even a man who’d been my mother’s grade school pupil. Of course, there were also people I didn’t know. Such a disparate crowd. My job, through the presentation of my words, was to make everyone feel they were part of a single group. It was my hope that my reading would make everyone a part of the 1844 story of the novel—a story of a woman accused of poisoning her husband, and a story of betrayal and redemption. That shared experience. Those shared emotions. For the roughly thirty minutes that I read, I hoped I’d make everyone feel just a bit more human, a bit more humane, a bit more alive.

The post The Shared Experience: Tips for Reading from Your Work appeared first on Lee Martin.

May 15, 2023

My Mother Gives Me a Writing Lesson

(In honor of Mother’s Day, I’m giving another life to this old post.)

(In honor of Mother’s Day, I’m giving another life to this old post.)

As I dream of spring on this cold January day, I’m reading through some old letters from my mother, written in her widowhood, and I’m struck by the sound of my own voice in hers and the lesson she offers the writer I’ll one day be about how to let the details evoke a life:

The little garden I have planted just stands there. No potatoes ever came up. I don’t know if it will grow when it warms up or not. If it does we might have some spinach or lettuce when you come home. But I can’t promise any. I’ve been using onions from those I set out last fall. I want to get some cabbage and cauliflower as soon as the stores get their plants.

Flannery O’Connor, in Mystery and Manners, talks about how the meaning of a story has to be made concrete through the details. “Detail has to be controlled by some overall purpose,” she says, “and every detail has to work for you.” She goes on to suggest that these details be gathered from “the texture of the existence” that forms the world of the story. “You can’t cut characters off from their society and say much about them as individuals,” she says. “You can’t say anything meaningful about the mystery of a personality unless you put that personality in a believable and significant social context.”

My mother wrote this letter to me while I was in the MFA program at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. A ten-hour drive separated me from her home, a home I’d had to leave her in alone because two weeks before the move to Fayetteville my father died. My mother was seventy-two at the time and she hadn’t had a driver’s license for some time. To leave her was, at that time of my life, the hardest thing I’d ever done. Now, as I read this passage from her letter, I find the essence of her life in those days rising from the details that she includes: the garden where the potatoes have refused to come up, the hope for spinach or lettuce when I return, the acknowledgment that she shouldn’t hope for too much, but still the dream of cabbage and cauliflower plants to come. Each detail expressing some aspect of what it was to be her at that time in her life, each detail holding the person she was in that place. If I encountered this passage in a story, I’d say I loved the writer’s trust in the details, and I loved how they so simply and yet elegantly created the meaning of this character’s life.

We fiction writers have to pay attention to the worlds of our characters and to the way the objects of those worlds become expressive. So with that in mind, here’s a writing exercise:

Gather the details of the setting of a story that you’re working on or one that you’ve completed to which you want to add more cultural texture. Pay attention to sensory details, not limiting yourself to the visual. What are the sounds of this place? The smells? The textures? The tastes? What are the customs?

Zero in on the details that are intimately connected to your main character. What do they show you about him or her that you didn’t know? What do they confirm about your character that you already thought you knew? Are the details, for example, expressive of certain cultural attitudes? Is your main character acting in accordance with the cultural influences of the setting, or is he or she acting in resistance to those attitudes?

Have your main character engage in an activity that is common in this culture—playing music for tips in the subway, for example, or planting flowers in the garden, attending the symphony or bingo night at the American Legion. Or have your character do something that would be considered out of place in this culture. The key is to have your character act from his or her relationship with the culture in which he or she lives.

Find a place within the scene to rely solely on details, ala the passage from my mother’s lesson, to express something essential, but something impossible to say directly, about your character’s life.

Our characters come from specific worlds. Whether by birthright or adoption, fiction writers cozy up to particular landscapes and use them to give their writing authority, contribute to characterization, suggest plots, and influence tone and atmosphere. The details of a place can create the characters and their actions.

The post My Mother Gives Me a Writing Lesson appeared first on Lee Martin.

May 8, 2023

Ask Lee

I ’ve been doing this blog for several years, and from time to time I get the feeling that I’m repeating myself. When that happens, I know it’s time for me to ask you what you want to know. Please send me your questions. I’ll try to get to them in the weeks to come. If I don’t have a good answer, I’ll ask for help and then rely on the community of writers to give me assistance. Our work is so solitary, we can forget that others are struggling with the same challenges. Consider this an invitation, then, to let me know what challenges you’re facing in your writing. Together, we’ll try to figure out a way to surmount those challenges.

’ve been doing this blog for several years, and from time to time I get the feeling that I’m repeating myself. When that happens, I know it’s time for me to ask you what you want to know. Please send me your questions. I’ll try to get to them in the weeks to come. If I don’t have a good answer, I’ll ask for help and then rely on the community of writers to give me assistance. Our work is so solitary, we can forget that others are struggling with the same challenges. Consider this an invitation, then, to let me know what challenges you’re facing in your writing. Together, we’ll try to figure out a way to surmount those challenges.

In the meantime, here’s something that’s been happening lately. As some of you may know, my wife Cathy had knee surgery almost two weeks ago. It was a revision of a full-knee replacement that she had in 2018. The surgeon had to replace the poly pad that rests between the two metal parts of the artificial knee. The first pad proved to be too thin, and the surgeon had to insert a thicker one. He also cleaned out a good deal of problematic scar tissue. Cathy’s rehab is going well. A few days ago, her quad muscle started firing, and now she’s able to lift her leg without help. She’s walking with the aid of a walker, but I fully expect her to be released to a cane this week. Of course, I’m always thinking from the perspective of a writer, so I see a lesson for us in the process Cathy has had to go through. Sometimes we have to adjust something we thought would, and sometimes we have to cut something out in order for things to work better. Such cutting is painful but necessary.

I also think about the courage it takes to give oneself over to any surgical procedure. After all, we never know with any degree of certainty what the result will be. The rehab process also takes a measure of grit and determination. It’s painful to do the exercises. When Cathy began hers, she couldn’t lift her leg without my help. Little by little, though, her strength is returning. We writers take a similar leap of faith when we face the blank page. We never know for sure what the result will be, but we forge ahead. I’ve written so many words over the years that have never seen publication. I know all those words were necessary for me to write the ones that made their way to readers. Our writers’ journeys are often painful ones due to disappointment and rejection, but that pain is evidence of the journey itself. We writers should wear our scars proudly. Those scars are proof of all we had to go through to get to where we are today.

Survive and thrive—that’s my motto. Keep working. Accept the pain that’s necessary for your improvement. Don’t be afraid to rely on those around you for support and guidance. This week is National Teacher Appreciation Week. I think of all the teachers who helped me along my journey, and how I’ve always tried to do the same for others. Let me know what you’d like to talk about. I’ll tell you what I know and what I don’t know. Together, we’ll work toward an answer, or at least a deepening of the question.

The post Ask Lee appeared first on Lee Martin.

May 1, 2023

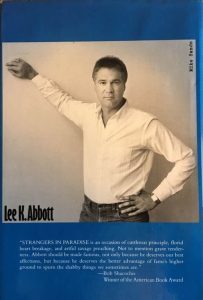

Lee K. Abbott and the Power of the Sentence

In remembrance of my former colleague, Lee K. Abbott, I offer the first sentence of his story, “Time and Fear and Somehow Love”:

In remembrance of my former colleague, Lee K. Abbott, I offer the first sentence of his story, “Time and Fear and Somehow Love”:

Since, as she conceived it, the letter was to be the final word on the subject, she endeavored to start slowly, then lead up to, as fine drama does, those moments of lamentation, those periods—always potent and manifold—of ruin and dismay which are like, her daddy had said once, many wildcats with wings.

Lordy, what an opening, one full of music and power that depends on the art of the pause. Read the sentence out loud and notice where the commas direct you to slow your pace for just a moment. The structure of the sentence mirrors what it’s come to express—the slow build to “those moments of lamentation, those periods—always potent and manifold—of ruin and dismay. . . .” Notice the final use of the caesura at the end of the sentence—“. . .which are like, her daddy had said once. . . .”—before the completion of the simile—“many wildcats with wings.” That pause for breath sets the stage for the stunning comparison of our moments of ruin to the startling image of wildcats with wings. The sentence ends with a bang, and it’s unforgettable.

Lee Abbott was a maestro with language. The above is only one small example of what a virtuoso he was. We could take a deeper dive into the opening sentence of “Time and Fear and Somehow Love” and mark the prose rhythm by highlighting the stressed syllables, particularly the first syllable of “potent” and the first and third syllables of “manifold,” and think about how those stresses emphasize “those moments of lamentation” and lead to the words, “ruin” and “dismay,” whose stresses amp up the tension of the sentence even more, taking us to it climax, the alliterative, “wildcats with wings.” This is a sentence that has a rise, “as fine drama does.” A sentence can be a story. Lee Abbott knew that.

I encourage you to read the work of other writers aloud, so you can hear what they’re doing on the sentence level. Oh, sure, there are many other elements of craft to practice when writing, but perhaps it all begins with an appreciation of a well-made sentence. Someone reminded me yesterday that I once said a well-made sentence was an attempt at salvation. Think of everything in the world that mystifies us. Think of all we can’t understand. A man in Texas killed five members of a family, including an eight-year-old child, because they asked him to please stop firing his automatic rifle; the gunshots were keeping their baby awake. How do we make sense of something like that? So often, the world is without reason or shape. One thing we writers can do to try to control the chaos is to write beautiful sentences. They may be slight ammunition against all that threatens us, but words are what we have, and if we can put them in the right order, who knows? Maybe we can make a difference. At least, we can believe this is so, which in the end, may be enough to save us.

The post Lee K. Abbott and the Power of the Sentence appeared first on Lee Martin.

April 24, 2023

Your Writer’s Journey

Here at the end of another semester, I’m reading work from my MFA students and thinking how privileged I am to be at least a small part of their writers’ journeys. Some of the students are completing their degrees and thinking about their next steps. I want to tell them, as I’m telling you now, that talent doesn’t always guarantee success. In fact, I’ve come to know that persistence is equally important, and even then—even if you’re dedicated to your craft—there’s no assurance that your career will go the way you want. In fact, there will probably be numerous ups and downs, more than you’ll be comfortable accepting. The downs may very well outnumber the ups.

Here at the end of another semester, I’m reading work from my MFA students and thinking how privileged I am to be at least a small part of their writers’ journeys. Some of the students are completing their degrees and thinking about their next steps. I want to tell them, as I’m telling you now, that talent doesn’t always guarantee success. In fact, I’ve come to know that persistence is equally important, and even then—even if you’re dedicated to your craft—there’s no assurance that your career will go the way you want. In fact, there will probably be numerous ups and downs, more than you’ll be comfortable accepting. The downs may very well outnumber the ups.

Don’t even get me started about the role luck and chance can play in a writer’s career. Let’s just admit breaks can come for us in ways we never could have predicted. We should never wait for them or expect them. We should work. We should practice our craft, so if a break or an opportunity comes, we’ll be ready to take advantage. Imagine how horrible you’ll feel if someone comes asking to see your work, and you have nothing to show.

Let’s also admit that talented, hardworking writers don’t always get published. If we’re totally honest, we’ll acknowledge that we never really know why. The capricious nature of the publishing business is beyond explanation, but if we can accept it, we can begin to focus on what we can control and stop worrying about what we can’t.

What we can control is the work itself. If we can be steady with our habits—if we can keep honing our craft—we may very well find ourselves being recognized by agents, editors, publishers, and readers.

The work is everything. As you go forward on your writer’s journey, do your best to put away envy and to escape the imposter syndrome that makes you feel you aren’t good enough, will never be good enough. That impostor syndrome never leaves us, no matter how successful we become. We all have that voice in the backs of our heads that tells us we’re bound to fail. Do what you can to silence that voice. Do what you love to do. Do it as well as you can. Let the results be someone else’s worry. Pay attention to the journey. If you can do that, it’ll always take you where you’re meant to go.

The post Your Writer’s Journey appeared first on Lee Martin.

April 17, 2023

Muscle Up: Writing Stronger Sentences

We prose writers spend so much time thinking about characterization and plot that we often overlook the importance of the artfully crafted sentence. “All you have to do is write one true sentence,” Ernest Hemingway famously said. “Write the truest sentence that you know.” His work strove for accuracy, honesty, and clarity, and it all began at the level of the sentence. William Barrett once said Hemingway’s style was “a moral act, a desperate struggle for moral probity amid the confusions of the world and the slippery complexities of one’s own nature. To set things down simple and right is to hold a standard of rightness against a deceiving world.” Think of the chaos of the world around us. Think of the mortality we all march toward. Think of our tenuous hold on this planet Earth. A clear, honest sentence begins to give shape, and perhaps even a moral structure, to an often shapeless and amoral world.

We prose writers spend so much time thinking about characterization and plot that we often overlook the importance of the artfully crafted sentence. “All you have to do is write one true sentence,” Ernest Hemingway famously said. “Write the truest sentence that you know.” His work strove for accuracy, honesty, and clarity, and it all began at the level of the sentence. William Barrett once said Hemingway’s style was “a moral act, a desperate struggle for moral probity amid the confusions of the world and the slippery complexities of one’s own nature. To set things down simple and right is to hold a standard of rightness against a deceiving world.” Think of the chaos of the world around us. Think of the mortality we all march toward. Think of our tenuous hold on this planet Earth. A clear, honest sentence begins to give shape, and perhaps even a moral structure, to an often shapeless and amoral world.

Let’s look at an example, so we can think about what goes in to making a true sentence. Consider the opening of Hemingway’s novel, A Farewell to Arms:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

Notice the details—the house, the village, the river, the plain, the mountains, the pebbles and boulders, the road, the trees and leaves, the troops, the dust, the soldiers. True sentences are made of concrete nouns. Notice, too, the motion of the sentences—the swiftly moving water, the troops marching, the dust rising, the leaves falling. A true sentence is kinetic. It moves. We might also look at the spare use of adjectives—dry and white, blue, dusty, bare and white. A true sentence does just enough to create a visual image and no more.

The second sentence, the one that describes the riverbed, relies on the caesura of an appositive—“dry and white in the sun”—to emphasize the details of the pebbles and boulders. The appositive asks the sentence to rest a moment while it offers the reader additional information before it resumes. If we read this sentence aloud stressing the accented syllables, we hear its points of emphasis. Try it—“peb-bles and bould-ers, dry and white, in the sun”—and listen to the heavy syllables marking points of emphasis. Poets aren’t the only writers who pay attention to the sounds language can make. Prose rhythm can contribute to the authenticity of a sentence by affecting the rate of delivery while pointing to what the readers should pay attention to.

Finally, notice what the sentences don’t say. They describe the passing of a season from summer to fall, but they don’t say a word about those marching troops and all they portend. Hemingway lets the details do that work. The fallen leaves on the bare road become an ominous image of what’s to come.

The world so often slips away from us, but a finely shaped sentence—a muscular sentence? That’s something we can control.

The post Muscle Up: Writing Stronger Sentences appeared first on Lee Martin.