Steven Hart's Blog, page 5

April 18, 2013

Getting the habit

This article about how novelists, painters, and filmmakers gear up for their work is interesting, but I think it’s chief value for neophyte writers is to get them thinking about methods and routines. I pottered about with fiction from the moment I understood what fiction was all about, but true productivity came when I established a routine and stayed with it. I had my sun-breaking-through-clouds moment while watching a 60 Minutes profile of P.D. James, who didn’t become a writer until her forties. James said she realized one day that nobody else cared about her creative drives, and if she was going to realize them she would have to get up an hour earlier every morning so she could work without being interrupted. That observation did it for me. I pissed away too many years thinking I would wait for inspiration. What I finally understood was that inspiration will find you more easily if you plant yourself in your workspace at a regular time every day. I don’t know if people who’ve read my stuff would consider it inspired. All I know is, I didn’t get anything done until I got tough with myself about establishing a routine. That’s the best lesson any writer — any artist — can learn.

April 7, 2013

That’s two big dragon heads up

The 1988 fantasy adventure Willow is nowhere close to being a good film, but this Behind the Scenes Photo feature at Ain’t It Cool News reminded me of its most distinctive feature: its anti-movie critic subtext, courtesy of producer George Lucas, who conceived the story but assigned directorial duties to Ron Howard. The chief villain is General Kael, whose name was a jab at the famous Pauline, and the two-headed dragon that makes a brief appearance in the middle of a battle was dubbed the Eborsisk by the effects team at Industrial Light and Magic. That name, of course, is a cock of the leg at Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, who doubtless incurred the great man’s wrath by dumping all over Howard the Duck, the big-budget fiasco Lucas produced in 1986. With Ebert’s death still in the news, some obliging film buff posted the clip of the Eborsisk in action:

April 5, 2013

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert may not have set out to become the world’s number one film critic, but circumstances made him so. When newspapers began their long dumb-down retreat from cultural life, Ebert was there to take up some of the slack. He had the Pulitzer, he had the name recognition, he had the television show, and he had the energy to churn out reams of wire copy. That was his great good fortune. Our good fortune was that Ebert, in a position where he could have spent the rest of his life coasting, decided to step up his game in a big way. Blessed with a reach and status enjoyed by no other critic, Ebert rose to the occasion and became a great one. There are many critics just as good as Ebert, but I doubt there will ever be another one who combines his talent with his wide-ranging impact. It’s standard for career retrospective pieces like this to end on a for-whom-the-bell-tolls note, but in Ebert’s case it’s more than appropriate. He really was the last of his breed.

Ebert was tagged early on as a “Paulette,” favored by the influential film critic Pauline Kael, and his best work shared her passionate engagement, disdain for deep-dish critical theories, and readiness to celebrate art (or, at least, craftsmanship) where he found it. But he started out as a rather callow and conventional reviewer. This early piece about George Romero’s seminal horror film Night of the Living Dead is a long whine about violence in movies, with only the last paragraph devoted to the real issue — that the theater owner should have been horsewhipped for showing such a  film as a kiddie matinee. The early months of Sneak Previews, the PBS show that made Ebert a household name, featured a stinker-of-the-week selection, complete with an appearance by Aroma the Educated Skunk, that invariably picked on some no-name release that hardly seemed worth the bother. The show’s chief attraction back then was the simmering dislike between Ebert and co-host Gene Siskel, and the chance of seeing it boil over on camera. (See above.) One of their themed shows presented movies they thought celebrated the American family, one of them being The Great Santini, a film that could serve as a legal defense of patricide.

film as a kiddie matinee. The early months of Sneak Previews, the PBS show that made Ebert a household name, featured a stinker-of-the-week selection, complete with an appearance by Aroma the Educated Skunk, that invariably picked on some no-name release that hardly seemed worth the bother. The show’s chief attraction back then was the simmering dislike between Ebert and co-host Gene Siskel, and the chance of seeing it boil over on camera. (See above.) One of their themed shows presented movies they thought celebrated the American family, one of them being The Great Santini, a film that could serve as a legal defense of patricide.

But the genius of Sneak Previews, at least during its initial 1975-1982 run, was that it tapped into the essential quality shared by all movie buffs — their love of argument. There are passionate fans for any art form, but movie geeks are in a class of their own in terms of their readiness to throw down at any moment. By pitting two pugnacious critics from competing newspapers, the format tapped into that argumentative streak. Over the years Ebert and Siskel became friends, but Siskel remained officially unimpressed by Ebert’s Pulitzer-laureled credentials, and he never hesitated to call bullshit on camera. About 3.33 into this clip, you’ll see Siskel berating Ebert for giving higher praise to Benji the Hunted than Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket:

Note that Ebert gives as good as he gets during the exchange, which both parties allowed to air without any edits or re-dos. It reflects well on bot parties that they didn’t mind being seen at sword’s points. That air of intellectual aggression between equals vanished when Siskel and Ebert left Sneak Previews and took their show on the syndicated road in 1982. (They were succeeded by journalist Neal Gabler, who left in 1985, and Jeffrey Lyons, an over-the-hill showbiz columnist so desperate for TV time that he stayed on as Michael Medved’s dog until the show was euthanized in 1996.) Bob Costas once got Ebert to admit on camera that he probably never would have enjoyed the same level of success with Siskel. Costas also got each man to describe what he envied most about the other during a 1992 interview:

Some critics are hunter-gatherers who range far and wide, seeking art in obscure corners and disreputable genres, then returning to bring readers the good news. Other critics are more like country club desk managers, categorizing high and low art in order to decide who will be allowed into the swimming pool area. Ebert was a hunter-gatherer. Like Kael, he was shaped by a period in which American filmmaking was breaking down barriers and exploring new artistic frontiers — a period in which movies were exciting in ways that went beyond the hyped-up marketing of peanut-brained behemoths like The Dark Knight Rises. Kael worked her way up through the decades when European and Asian films were making their first serious inroads into American viewing habits; Ebert wrote about those films (and the later works they influenced) with an appreciation that was clearly shaped by Kael’s critical judgments. When American filmmaking narrowed, Ebert responded by widening his focus: no critic of comparable stature devoted as much space to foreign works. In May, when the studios usually rolled out their big summer blockbusters, Ebert was at the Cannes film festival, prospecting for works of promise and greatness, and sending dispatches back Stateside. One of the great pleasures of working as a wire news editor in the Nineties was the opportunity to read those dispatches, unedited, even though the paper I worked for would never use them.

Ebert was a man of sides. He worked with exploitation king Russ Meyer on the film Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, and reteamed with him for the never-realized Sex Pistols film Who Killed bambi He was an unabashed science fiction fan, and had actually published stories in genre magazines before turning his attention to full-time reviewing. During the Nineties, when his critical writing truly bloomed, Ebert also showed himself to be a shrewd writer on politics. When the Gingrich gang was on its contemptible jihad against Bill Clinton, Ebert’s response to the campaign of humiliation against the president was as discerning as it was outraged. Perhaps for that reason, when the smoke cleared, Ebert has granted an interview with Clinton as well as a screening in the White House movie theater.

The love of argument overlapped with the instinct to teach and inform. He did DVD commentaries for six films, and an idiosyncratic, wide-ranging bunch they are: Casablanca, Citizen Kane, Ozu’s Floating Weeds, Terry Zwigoff’s documentary about Robert Crumb, the cult fantasy Dark City, and, naturally, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. Now, Citizen Kane is one of my favorite flicks — I’ve read biographies of Orson Welles, even Kael’s much-maligned essay “Raising Kane.” But I found the flow of information on Ebert’s Citizen Kane commentary so exhausting that I had to switch it off halfway through and go staggering into the kitchen for a couple of boilermakers. The man knew his onions.

The love of argument also led him to the Internet, that nonpareil domain for never-ending debates. Ebert dove into the Internet head first in a way that few other critics matched, and his website remains a model for all writers. When websites like Ain’t-It-Cool News were still being derided as watering holes for unhygienic dorks, Ebert invited AICN ubergeek Harry Knowles to share the balcony with him. Late in life, as recurring bouts of cancer sapped his strength, Ebert turned his site into a meeting place for movie writers from all over the world, giving Stateside readers a chance to see how Hollywood films affected their counterparts in India and elsewhere. The collapse of the newspapers and magazine that once hosted film critics (as well as reviewers in all other fields) may have saddened him, but Ebert knew the intellectual fizz of cultural commentary had moved to the digital realm, and he made himself comfortable there early on.

There are plenty of great film websites and lots of fine film writers on the Internet. I have my favorites; you have yours; tomorrow we’ll both find plenty more to follow. The collapse of credentialism has, overall, been a good thing for criticism. One need only look back to the days of Bosley Crowther, or some snobbish bit of snark in the New York Times, to recognize that pedigree and critical judgment don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand in the arts. But I’m old enough to remember when there were lots of magazines and newspapers worth following and arguing about, and I miss them. Ebert was the last great writer to cross that landscape, and the last to enjoy the kind of clout that came with the role. As Lester Bangs once said about Elvis Presley, we will never agree about anything the way we agreed about Roger Ebert. We really are moving into a new realm, and one of the compass points for getting around in it is now gone for good.

April 3, 2013

Coming this fall

Rutgers University Press just sent me the prototype cover for American Dictators: Frank Hague, Nucky Johnson, and the Perfection of the Urban Political Machine. I’ve also just gotten two terrific advance blurbs from some well-regarded nonfiction writers, which I’ll pass along in a little while. But meanwhile, I just want to contemplate this cover for a bit. By “contemplate,” of course, I mean “gloat.”

March 21, 2013

From Steinbeck to Hane to Bach, by way of Ixtlan and Li Po

Culture is a slippery slope. One thing leads to another. A book leads to a poem, or a piece of music, or a painting, and suddenly you’re haring off after something else entirely.

We’re coming up on the birthday of Johann Sebastian Bach. Even if you don’t know him, you know his music. Even if you don’t like classical music and avoid it like the plague, you’ve heard something by Bach. One of the pleasures of getting to known the man’s immense body of work is the little epiphany you get every now and then, realizing something he wrote — Toccata and Fugue, anybody? — has been imitated and recycled so many times that it has permeated the cultural aquifer.

We’re coming up on Bach’s birthday, and at the top of the post is the cover of the first Bach album I ever bought — Book Two of The Well-Tempered Clavier, performed by Glenn Gould. If memory serves, I scored my copy at a long-vanished record store in the Moorestown Mall. The thing is, I wasn’t looking for The  Well-Tempered Clavier, I was looking for The Art of Fugue. That’s because my favorite book at the time, the book I re-read at least three times that year, was John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row, which I still think is the best thing he ever wrote — second only to The Pastures of Heaven. And if you’ve read Cannery Row, you know the novel is, among other things, a song of devotion and admiration for Ed Ricketts, the Monterey-based marine biologist Steinbeck used as the basis for Doc, the novel’s scientist hero. Along with being a scientist, heavy drinker, and epic lover of women, Doc was also passionately fond of The Art of Fugue, and while the teenaged me could at the time only dream of indulging in the first three, I could damn well score myself a copy of Bach’s valedictory work.

Well-Tempered Clavier, I was looking for The Art of Fugue. That’s because my favorite book at the time, the book I re-read at least three times that year, was John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row, which I still think is the best thing he ever wrote — second only to The Pastures of Heaven. And if you’ve read Cannery Row, you know the novel is, among other things, a song of devotion and admiration for Ed Ricketts, the Monterey-based marine biologist Steinbeck used as the basis for Doc, the novel’s scientist hero. Along with being a scientist, heavy drinker, and epic lover of women, Doc was also passionately fond of The Art of Fugue, and while the teenaged me could at the time only dream of indulging in the first three, I could damn well score myself a copy of Bach’s valedictory work.

Only I couldn’t find The Art of Fugue in any record store, and in the pre-Amazon landscape of the mid-Seventies it was a rare and lovely thing to find a record store willing to do special orders. Even so, I’d been wanting to take a crack at Bach — I approached album purchases as a form of self-improvement back then — so I thumbed through the bins in search of something that looked promising. That’s when I saw the angel-coiffed Bach staring back at me.

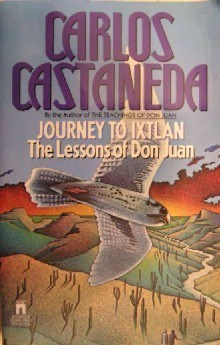

Another of my high school, fixations, along with Steinbeck, was the works of Carlos Castaneda and his (probably imaginary) encounters with the Yaqui Indian seer Don Juan Matus. The covers of A Separate Reality and Journey to Ixtlan sported the magnificent cover art of Roger Hane, whose style was so instantly recognizable that I had to get that particular Bach album. There was even a full-sized wall poster of the cover illustration. Hane also painted the covers for the 1970 Collier paperback edition of The Chronicles of Narnia. (Hane was killed by muggers in 1974, and when the fourth Don Juan book, Tales of Power, came out I was pleased to see the cover artist had written “For Roger” over his own signature.) So I proceeded to work my way through the entire Well-Tempered Clavier, and when The Art of Fugue finally turned up, I found it to be every bit as good as Steinbeck (and Doc) had promised.

for the 1970 Collier paperback edition of The Chronicles of Narnia. (Hane was killed by muggers in 1974, and when the fourth Don Juan book, Tales of Power, came out I was pleased to see the cover artist had written “For Roger” over his own signature.) So I proceeded to work my way through the entire Well-Tempered Clavier, and when The Art of Fugue finally turned up, I found it to be every bit as good as Steinbeck (and Doc) had promised.

Cannery Row, as well as the essay “About Ed Ricketts” from The Log from the Sea of Cortez, included paens to the work of Li Po, and in due course I found the collected works of that drunken Chinese poet. Another bell ringer.

See what I mean? It’s a slippery slope, this culture business. One thing leads to another. And all this because we’re coming up on Bach’s birthday.

March 7, 2013

Surf’s up

Now that the Jersey Shore has taken yet another pounding from a winter storm, it may be time to spend some idle moments with this N.J. Flood Mapper, prepared by Rutgers University to show the effect of rising sea levels on selected areas of the Shore. Let’s just I’m revising my fantasy of owning a house by the ocean.

March 1, 2013

Sadie

My dog Sadie, founding member of Clan Westie and endless source of delight to anyone who knew her, is gone. After years of steadily declining health and mobility, she reached the point where a dog of her age (she was sixteen in dog years) could only look forward to more pain, despite the meds we had been giving her for the past year. Last night I petted and soothed her as the veterinarian gave her a sedative, waited for her to fall asleep, then administered the final shot.

In the comedy troupe that was Clan Westie, Sadie was the bossy one. She would fix you with her piercing black Westie eyes and subject your eardrums to a series of imperious yips that demanded instant obedience and delivery of whatever service she wanted at that moment. Late in the life, that usually meant she wanted to be lifted onto the couch.

Her biggest problem in life was that Wee Laddie, the Westie who came home with her, was a bit heavier and a lot more rambunctious. When he decided to open up a can of whoop-ass on her, she gave as good as she got, but she would use strategy. When he started charging around the back yard, she would stand under one of the lawn chairs — not to hide, mind you, but to keep her opponent from triumphing through sheer momentum. Whenever he slowed to look for a way in, she would spring out and scrap with him.

Sadie was the nicest birthday present I’ve ever gotten, given to me in the nicest way imaginable. My wife at the time came to get me, ordered me to wear a blindfold, then told me to wait in the parking lot, still wearing the blindfold. After about five minutes, a soft weight was placed on my chest and Sadie covered my face with the first of many kisses.

Sadie was the scourge of squirrels — or would have been, if only one had fallen from the trees. She would stand at the foot of a tree, tail held high like Cyrano’s panache, barking warnings of certain doom to the squirrels looking down from branches about twenty feet up. She also had cat issues, but since she wasn’t stupid, she only chased them when the Wee Laddie was beside her. This happened early on, when she and the Wee Laddie staged almost weekly jailbreaks from the back yard until I instituted Stalag 17 security measures.

She had a soft, silky coat, not as coarse as the other dogs, and it was very hard to stop petting her. I can feel the texture on the palms of my hands as I write this.

Her decline was terribly sad, because she had been so funny and scrappy. Her hind legs grew all but unusable, and she suffered spells in which she wandered, dazed, making little screeching yelps. The screaming stopped once we put her on meds, but she was only conscious long enough to eat and do her thing outside. Near the end, her hindquarters never stayed up, even after we lifted them and held her steady for a few beats.

When I gave the go-ahead, the veterinarian placed Sadie on the floor, on a warm thick towel, so she wouldn’t feel anxious about being on the high metal table. As she relaxed into her sleep, the lines of her body softened. She looked like her old self again. She had been in such bad shape for so long, I’d almost forgotten what she looked like in her prime. She went to sleep with hands soothing and stroking her, with voices she knew and trusted speaking her name and telling her she was a good girl. The doctor administered the final dose, then listened to her heart through the stethoscope. “She’s gone,” he said.

We bring these little souls into our lives and look after them, and after a time we realize that they are looking after us, as well. Sadie was one of my best and smallest friends, and I’m confident she spent every waking moment of her life certain in the knowledge that she was loved. That’s a comforting thought right now as I blink at this blurry screen, missing her terribly. When I’m done here, I’m going to grab the Wee Laddie and give him a belly rub he’ll never forget. Because what would be more appropriate?

February 25, 2013

David Letterman is happy this morning

I didn’t watch all of last night’s Oscar broadcast, but I did watch enough of it to conclude that if Seth MacFarlane did nothing else, he made David Letterman very happy. I’m sure Letterman slept like a baby last night, content in the knowledge that he is no longer the worst Oscar host on record.

I had the same feeling watching MacFarlane’s performance that I got watching his cartoon, Family Guy. I duly noted the fact that my outrage button was being pushed — hammered, actually — but nothing registered because there was nothing resembling wit behind the mechanically delivered outrage. The early skit with Captain Kirk telling MacFarlane his jokes were tasteless and crass may have been intended as inoculation — Look, I’m so edgy I even criticize myself going in! — but it ended up being more of a prophecy. I’ll credit MacFarlane with looking cool and poised throughout a long, demanding broadcast. The flop sweat was all in his material.

For the record, I’m perfectly happy that Argo got the biggie, Daniel Day-Lewis got another gold guy. (Christy Brown, Daniel Plainview, Abraham Lincoln — what a roster!) and Jennifer Lawrence got her crown. I haven’t seen Life of Pi, but Ang Lee is a real talent. It was cool seeing Shirley Bassey belt out the Goldfinger theme song, then Adele doing the same for Skyfall, its only peer in the Bond canon.

To show their appreciation, I suggest the Academy voters commission a special Oscar for Seth MacFarlane: a statuette with the hands clenched a little below waist level, to commemorate what Edgy Guy got to spend the night doing in front of millions of viewers.

February 16, 2013

I’m Pynchon myself

In all of the newspapers where I’ve worked, editors always seemed to be hyper-vigilant against the possibility that somebody might sneak a literary reference past them. Something that might actually appeal to actual readers, God forbid. So I’m astonished to see this Boston Globe headline about the meteor explosion in Russia:

Jim Romenesko bird-dogged it (and J.D. Rhoades spread the word). Of course it’s the opening sentence of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow, a certified classic of American literature. It’s a very clever idea for a headline. It’s also a very intellectual idea for a headline, which makes it all the more astonishing that it got through. It took me a while to grasp that in a newsroom, being called an “intellectual” is not quite an insult, but certainly far from a compliment. Old school newsies liked to imagine themselves sitting on a barstool next to Slats Grobnik, too busy talking sports and insider politics to bother with pishy-poshy ivory tower stuff. I pissed away entirely too much time arguing with editors who never saw a baseball reference they didn’t like, but would have had multiple aneurysms at the mere thought of a Thomas Pynchon reference tip-toeing into their news columns.

But enough of my joy. Let’s just note the classy touch on the Boston Globe story, and hope the headline writer doesn’t get in hot water.

February 13, 2013

The Parker files

Blunt dialogue, lean action, minimal exposition . . . you’d think the Parker novels would be naturals for Hollywood. But the antihero created by Richard Stark (aka Donald Westlake) is a tough pill for story editors in search of — how do they put it? — characters we can care about. This makes for some highly variable movies.