Steven Hart's Blog, page 10

October 18, 2012

Q&A

Yours Truly is interviewed by Pat Bertram over at her website. The subject is . . . oh, I don’t know. Some book I wrote. You’ll see.

October 16, 2012

Eat the world

I’ve never suffered from that strange malady called writer’s block, but I have had times when I’ve felt stale and uncreative. At such times, I turn to author interviews — not just short items, but serious interviews in which both parties are fully engaged on a creative and intellectual level. The best place to find them is in The Paris Review, but they can turn up anywhere and they never fail to clear away the cobwebs and renew my eagerness to get on with the work.

Jeff VanderMeer’s interview with the much-laureled writer Junot Diaz meets that standard and then some. Not only is it a fine interview, but the closing line is like a double-caffeinated shot of whiskey for any writer.

October 14, 2012

Behind the curve

When I read this description of Tom Wolfe’s imminent fourth novel, Back to Blood, my first reaction was: I thought Carl Hiaasen wrote this already. Several times, in fact. Along with James W. Hall, Charles Willeford, Edna Buchanan and all the other Florida Noir authors who’ve been wringing the state dry for stories since the Eighties. It’s kind of sad to see the man in the ice cream suit lagging so far behind the Zeitgeist on this, like Elton John releasing his disco album after even the Bee Gees had moved on.

Meeting on the fringe

Apropos of yesterday’s review of The Master, here’s an out-of-the-blue New Republic article about the growing relationship between Scientology and the Nation of Islam. I almost wrote “unlikely alliance,” but as the article makes clear, there’s a lot more overlap in their worldviews than you might think.

October 13, 2012

Reasons to believe

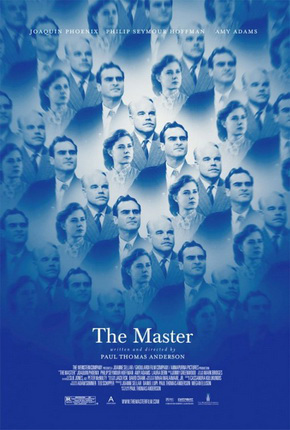

Though it arrives after a five-year interval, Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film The Master plays like a companion piece to his previous, There Will Be Blood. Both works are built around a tense, frequently explosive relationship between a smooth-talking messianic figure and a gimpy, black-haired obsessive prone to bursts of startling violence. Both There Will Be Blood and The Master climax with bogus preachers confessing their fraudulence, but where in the earlier film confession was a prelude to savage madness, in The Master it serves as a benediction leading to a surprisingly sweet resolution.

Though it arrives after a five-year interval, Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film The Master plays like a companion piece to his previous, There Will Be Blood. Both works are built around a tense, frequently explosive relationship between a smooth-talking messianic figure and a gimpy, black-haired obsessive prone to bursts of startling violence. Both There Will Be Blood and The Master climax with bogus preachers confessing their fraudulence, but where in the earlier film confession was a prelude to savage madness, in The Master it serves as a benediction leading to a surprisingly sweet resolution.

I don’t want to lean on the comparison too hard: The Master stands on its own two feet in Anderson’s catalogue, even as it rises head and shoulders above most of this year’s other serious movies. In There Will Be Blood, belief was shown as something of a natural resource, exploited by Eli Sunday as relentlessly as his antagonist Daniel Plainview drilled for oil. The Master is about the need for belief, and how that need — even when manipulated by an obvious huckster — is not necessarily a bad thing.

I have no clue as to Anderson’s religious or spiritual leanings, but after seeing The Master I realized that the need for belief is a theme running through all of his work to date. In his debut feature, Hard Eight, a man commits murder to protect the illusion that has enabled another man to get himself out of the gutter. The porn-industry players in Boogie Nights are sustained by their insistence on seeing themselves as something more than items off a meat rack. Even the uber-nerdy hero of Punch-Drunk Love warns an enemy that being in love has given him the strength and will to defeat all challengers. None of this is shown with even the tiniest trace of sentimentality, least of all in The Master. Anderson’s films may be warmer than those of Stanley Kubrick and Robert Altman, his acknowledged models, but he is every bit as observant in capturing human frailty.

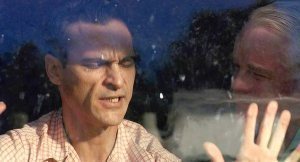

Like its predecessors, The Master is rooted in a very particular period of history, which it evokes with an unshowy but very exacting attention to detail. Here it is the prosperous decade immediately following World War II, when America truly dominated the world. The main character, Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), has emerged from the Navy with a full complement of physical and psychological wounds and no apparent skills beyond the ability to concoct Sneaky Pete from whatever chemicals come to hand. (At least Daniel Plainview stuck with whiskey; we get our first look at Freddie as he slurps torpedo fuel.) Infantile in his behavior, wracked by sexual fixations and barely able to interact with others, Freddie is too damaged to take part in the postwar prosperity, and he quickly drifts to the bottom of society. With no likely prospects beyond dying in a ditch, Freddie impulsively stows away on a yacht and comes face to face with Lancaster Dodd  (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a slickly plausible con man who has set himself up as the head of a self-help cult called The Cause.

(Philip Seymour Hoffman), a slickly plausible con man who has set himself up as the head of a self-help cult called The Cause.

Early reports on The Master said it was a roman a clef about L. Ron Hubbard and the early years of Scientology, and Anderson references Hubbard’s fixation on ships and the sea throughout the film. When Dodd offers Freddie free “processing” to unearth his inner demons, the repetitive questioning seems based on what I’m told are the early stages of Scientological training. We learn nothing of Dodd’s background, which is too bad — Anderson could have mined Hubbard’s pre-cult career as a science fiction writer to great comic effect. (Check out these scathing reminiscences from Frederik Pohl’s blog for examples.) It’s no surprise that John W. Campbell, the landmark science fiction editor who became an insufferable crank in his later years, fell in love with Dianetics, the precursor of Scientology. Campbell’s view of the future (echoed by many other genre writers at the time) boiled down to opinionated white guys with engineering degrees setting the universe straight; why not have those same opinionated white guys conquer the inner space of the mind as well? When Freddie asks what he does, Lancaster Dodd responds with a list of titles straight from the mouth of one of Robert A. Heinlein’s “competent man” characters. But the fraudulence leaks through in the way Dodd carefully parses his sentences, as when Freddie asks if he owns the yacht, and Dodd replies, “I am its captain.” After all, any two-bit Bible banger has tried-and-true dodges at his disposal. Dodd, applying a pseudo-scientific sheen to spiritual bunk, constantly has to improvise, and he can’t always bring it off. In these clumsy moments, the less-than-masterful master is almost endearing.

There are no bad performances in any of Anderson’s films, but Punch-Drunk Love and, especially, There Will Be Blood showed him moving away from the large ensembles and naturalistic acting of his first three films, and toward stories built around one or two actors giving highly mannered performances. As played by Joaquin Phoenix, Freddie is a twisted rag of a man, starved to the bone, with a mouth perpetually curled to suggest either a grimace or a sneer — when we see him lurching through his job as a portrait photographer, Freddie is like a refugee from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari stranded in a department store. Dodd, all  well-fed confidence and poise, is his perfect foil — Hoffman doesn’t so much play the role as soak it in through his skin. Unlike Eli Sunday, whose charismatic preaching seemd sincere (albeit grotesque) right up to the climax of There Will Be Blood, Dodd can’t keep his mask from slipping whenever The Cause gets questioned a little too closely or persistently. Late in the film there’s a memorable scene in which Dodd, tired and distracted after a day’s con-artistry, is approached by a well-meaning devotee (Laura Dern) whose need for clarity triggers a burst of rage as intense as a nuclear test in the desert. She’s so cowed she can’t bring herself to look straight at him, but her sidelong glance makes it clear she’s finally figured things out.

well-fed confidence and poise, is his perfect foil — Hoffman doesn’t so much play the role as soak it in through his skin. Unlike Eli Sunday, whose charismatic preaching seemd sincere (albeit grotesque) right up to the climax of There Will Be Blood, Dodd can’t keep his mask from slipping whenever The Cause gets questioned a little too closely or persistently. Late in the film there’s a memorable scene in which Dodd, tired and distracted after a day’s con-artistry, is approached by a well-meaning devotee (Laura Dern) whose need for clarity triggers a burst of rage as intense as a nuclear test in the desert. She’s so cowed she can’t bring herself to look straight at him, but her sidelong glance makes it clear she’s finally figured things out.

In The Master, the real issue is the nature of Dodd’s relationship with Freddie, which puzzles Dodd’s circle and alarms his wife (Amy Adams), who understands The Cause is the only thing standing between their family and penury. At first, Freddie seems to present Dodd with a worst-case challenge; if he can help this damaged specimen, maybe The Cause offers something real after all. Ironically, the processing sessions do seem to have an effect on Freddie, just as Scientology (at least in its early stages) appears to benefit some people — certainly Tom Cruise credits it with making him one of the biggest movie stars on the planet. In a further irony, wises Freddie up to Dodd’s fakery even as it makes him a slightly more functional human being. When Freddie and Dodd finally part ways, Dodd’s valediction comes across as a wink from one con-man to another — “If you find a way to live without a master, without any master, let us know. You’d be the first person in the history of the world.” We then see Freddie picking up a woman at a bar and giving her a garbled version of Dodd’s processing spiel during their pillow talk. The Cause may not be real, but at least it has given Freddie something new in life — a relatively harmless way to get over on people.

As I said, there is nothing sentimental about The Master. Dodd is never shown as a loveable scamp — indeed, there’s always something creepy about him even in his best moments — and we are never encouraged to see his marks as deserving of their victimization. The film’s take on belief, and the need for belief, is far more subtle than that. It helps to remember that the central relationship begins when Dodd samples and enjoys one of Freddie’s improvised brews. “Is this booze you make poison?” Dodd asks during one session. “Not if you drink it smart,” Freddie tells him. That line takes on greater significance every time I think about it.

October 7, 2012

Bruno’s tunes

Regular readers of this blog — to the extent that such people exist — know of my admiration for Dr. Jacob Bronowski, still best known for his magnificent BBC series The Ascent of Man. While doing some research, I came across this January 1974 entry in the BBC’s Desert Island Discs program, in which Bruno listed eight records he would take with him for castaway duty. Bronowski was a formidable polymath but he often joked that music was a language in which he stuttered. Despite all that, his list is intriguing: Winterreise alongside The Threepenny Opera, Ewan MacColl rubbing elbows with Marlene Dietrich, Benjamin Britten playing next to Tom Lehrer. Of course, Lehrer and Bronowski were both mathematicians; when you hear Bronowski’s remarks about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, you’ll realize the two men shared other qualities as well.

October 6, 2012

Blurbito ergo sum

Two unexpected bits of coolness that come with publishing a nonfiction book: (1) Seeing yourself cited in bibliographies and footnotes, and (2) being approached for cover blurbs by other writers in your line. Which is a roundabout way of saying that not only is the just-published Killing the Poormaster: A Saga of Poverty, Corruption, and Murder in the Great Depression a great book that deserves lots of attention, but it also marks my debut as a blurber. Not just on the dust jacket, either –I’m right before the title page, rubbing inky elbows with Anthony DePalma and Fred Gardaphe. Tell Mr. DeMille I’m ready for my close-up.

Holly Metz has written a historical page-turner centered on the February 1938 death of Harry Barck, a petty city official in Hoboken, N.J., who used his position as “poormaster” to grind impoverished city residents under his heel. To borrow phrase from Jimmy Breslin, Barck died of natural causes — his heart stopped beating when a paper spike was thrust into it. For the scores of Hoboken residents who’d had their assistance arbitrarily cut back because of Barck’s views on self-reliance, and the families forced to get by on resources that would have been inadequate even for one person, the poormaster’s death was a source of grim satisfaction. An unemployed mason, Joe Scutellaro, was charged with murder; Scutellaro claimed the death was accidental, saying he had fought with Barck after the poormaster suggested his wife should turn tricks instead of asking for aid from the city.

The ensuing trial turned the spotlight on the way America treated its impoverished citizens during hard times, and Holly Metz’ book picks out some even more glaring parallels with our current economic and political situation. The depth of research is evident on every page, but Metz’ prose is quick and light on its feet. Hoboken may have gone from roughneck to ritzy over time, but one of the most important things you’ll learn from Killing the Poormaster is this: The past is always closer than you think.

October 4, 2012

Ripping yarn

Nicholas DiGiovanni, my stablemate at Black Angel Press, will be busting out all over, doing readings for his debut novel, Rip. You should go. It’s a great book, and you’ll have a good time.

October 3, 2012

An almost-perfect storm

Pam Stack, co-host of the Authors on the Air program that featured me and We All Fall Down a few months ago, is guest-blogging for J.D. Rhoades, who provided a wonderful cover blurb for the novel. Read, listen, be informed, be entertained.

Oscar wow

Junot Diaz has sure come a ways in the world since I interviewed him, lo those many years ago. I had read his short story “Edison, New Jersey” in the Paris Review, and since I wrote for a newspaper that covered Middlesex County I sought him out — after all, how many times does one expect to see Edison name-checked in the Paris Review. For the purposes of my newspaper, the Diaz article was a hat trick — Diaz was born in the Dominican Republic but raised in London Terrace, with connections to Elizabeth, and a degree from Rutgers University in New Brunswick. All three coverage areas in one story! High five, baby!

What made the article truly enjoyable, of course, was the quality of the man’s work, which was demonstrated many times over when his story collection Drown appeared in bookstores. Since then, the guy’s had a charmed career. His first novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, appeared after a long interval and was garlanded with rave reviews and a Pulitzer Prize. Now another collection, This Is How You Lose Her, is out just in time for Diaz to score a genius grant. And now he’s going to write a science fiction novel. More power to him.

All I ask is that the Nobel committee wait a decent interval before giving Diaz a call. He’d have nowhere to go after that, and I want this good-guy-finishes-first story to keep rolling.