Andy Worthington's Blog, page 92

August 23, 2015

Ignoring President Obama, the Pentagon Blocks Shaker Aamer’s Release from Guantánamo

I’m just back from a fortnight’s family holiday in Turkey (in Bodrum and Dalyan, for those interested in this wonderful country, with its great hospitality, history and sights), and catching up on what I missed, with relation to Guantánamo, while I was away. My apologies if any of you were confused by my sudden disappearance. I was working so hard up until my departure that I didn’t have time to put up an “on holiday” sign here before heading off.

I’m just back from a fortnight’s family holiday in Turkey (in Bodrum and Dalyan, for those interested in this wonderful country, with its great hospitality, history and sights), and catching up on what I missed, with relation to Guantánamo, while I was away. My apologies if any of you were confused by my sudden disappearance. I was working so hard up until my departure that I didn’t have time to put up an “on holiday” sign here before heading off.

Those of you who are my friends on Facebook or who follow me there will know that I managed to leave a brief message there, announcing my intention to be offline for most of the two-week period — and encouraging you all to take time off from the internet and your mobile devices for the sake of your health!). While away, my Facebook friends will also know that I touched on one of the most significant Guantánamo stories to take place during my absence — the disgraceful revelation that, despite having been approved for release in 2010 by a thorough, multi-agency US government review process (the Guantánamo Review Task Force, established by President Obama shortly after taking office in January 2009), Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, is still being held because of obstruction by the Pentagon, and, moreover, that the Pentagon has specifically been blocking his release since October 2013.

The story appeared in the Guardian on August 13, following a Washington Post article three days earlier, in which, during a discussion about the Obama administration’s quest for a prison on the US mainland that could be used to hold Guantánamo prisoners, it was noted that, in a meeting last month with President Obama’s top national security officials, defense secretary Ashton Carter “indicated he was inclined to transfer Shaker Aamer.” By law, the defense secretary must certify that steps have been taken to mitigate any possible risk posed by released prisoners, and provide Congress with 30 days’ notice of any planned releases.

The Post article stated out that, since he took over in February, Carter “has approved the resettlement of six inmates in Oman,” although that transfer “was the second part of a larger deal that had been in the works for over a year to resettle 10 Yemeni citizens in the Persian Gulf sultanate.” It was also noted that administration officials said that Carter “recently approved the transfer of another detainee who has yet to be released.” According to the officials, “a deal was reached two years ago with the country that has agreed to accept that detainee,” who was not named.

In the Guardian‘s follow-up article, Spencer Ackerman cut through the rather more upbeat tone of the Post‘s article by stating that “US officials said they reached a deal with their British counterparts on transferring Aamer at a meeting in Washington in October 2013, subject to final approval from senior officials. The Pentagon has been the holdout.” Ackerman added that, “even as the White House pledged to make his case a priority after a personal plea from David Cameron, Barack Obama’s defense secretaries have played what one official called ‘foot-dragging and process games’ to let the deals languish.”

Ackerman explained that this opposition by the Pentagon “helps explain why Aamer has remained at Guantánamo despite bipartisan anger from the United States’ closest international ally.” One “frustrated” British official said, “A slap in the face is right,” agreeing with the description of the appalling treatment of Shaker Aamer in an op-ed in the New York Times by the delegation of British MPs — the Labour MPs Jeremy Corbyn and Andy Slaughter and the Tory MPs David Davis and Andrew Mitchell — who visited Washington D.C. in May to call for his release.

The Guardian explained correctly that, “In the UK, Aamer’s continued detention is a cause célèbre. In addition to the June ‘slap in the face‘ article, last month a politically diverse coalition of signatories ranging from London mayor Boris Johnson to Sting urged Obama to release Aamer as a method of restoring ‘America’s notion of itself and its international standing.'” That was the letter I wrote for the We Stand With Shaker campaign, which I co-founded with the activist Joanne MacInnes last November.

The Guardian also noted that two other men are awaiting release, one of whom was first mentioned in April in a Washington Post article, which I wrote about here, and which suggested that his release– and that of Shaker Aamer — was imminent. That man is Ahmed Ould Abdel Aziz, a Mauritanian, and the Guardian noted that “US diplomats reached an agreement to transfer Abdel Aziz in fall 2013.” The third man apparently awaiting approval for release is Abdul Rahman Shalabi, a Saudi and a long-term hunger striker, who was approved for release on June 15 by a Periodic Review Board, a review process established in 20123 to review the cases of the majority of the rinsers not already approved for release by Obama’s task force in 2010.

According to the Guardian, “The state department has deals in place with the three detainees’ home countries that still await Carter’s signature.”

In Shaker Aamer’s case, as the Guardian put it, Carter, “backed by powerful US military officers, has withheld support for sending Aamer back to the UK,” obstruction that “has left current and former US officials who consider the detainees a minimal threat seething, as they see it undermining relations with Britain and other foreign partners while subverting from the inside Obama’s long-stifled goal of closing the infamous detention facility.”

The Guardian added that Obama administration officials were careful to point out that the Pentagon “has never formally opposed the transfers,” which would be “an act of outright resistance to a high-profile presidential commitment that risks reprisal.” Ackerman noted that the transfers “have the backing of the US Justice Department, the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence,” but added that, “since White House rules depend on full administration consensus, Aamer remains at Guantánamo until Carter and the Pentagon say otherwise.”

Discussing Ashton Carter’s reluctance to sign off on any prisoners releases, the Guardian explained that “Chuck Hagel’s reluctance to closing Guantánamo contributed to his firing last year, but successor Carter has not proven any more pliable.” An official who “spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss a topic of significant internal acrimony within the Obama administration,” delivered a blunt assessment: “Carter is worse.”

Writing of the defense secretary’s alleged inclination to release Shaker Aamer, Spencer Ackerman noted that “the high-level meeting last month at which Carter expressed that sentiment was supposed to have been a forum to finalize decisions on transferring extant detainees, leaving other officials with the impression that Carter was continuing to stall while appearing cooperative.”

Ackerman also noted, “The well of opposition to the transfers does not end with the defense secretary. Carter is supported by the staff of the outgoing chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, as well as the powerful General John Kelly, head of US southern command, which oversees Guantánamo.”

Ackerman also claimed that Paul Lewis, appointed by President Obama as the envoy for Guantánamo closure in the Pentagon in 2013, was “seen as marginalized and ineffective,” with one official calling him a “non-factor.” Referring to the Pentagon, the official said, “The building doesn’t want to do it.” However, Brian McKeon, a senior Pentagon policy official, defended Lewis, calling him “integral to the process of ending detention operations at Guantánamo Bay,” and stating, “He works closely with the secretary and other high-level leaders in the defense department and throughout the interagency, as well as with our international partners and members of Congress,” and adding that Lewis has “enabled President Obama and Secretary Carter to achieve significant progress towards their shared goal of closing the detention facility at Guantánamo Bay in a responsible manner”.

In his article, Spencer Ackerman also revealed that, for years, the Pentagon “has forced the other US agencies through a laborious process of requiring additional information about how the transfers of Aamer and Abdel Aziz will work, something officials outside the Pentagon consider a delaying tactic.” He added that concern was mounting that the delays would “make it harder for US diplomats to convince other countries to accept Guantánamo detainees.”

Describing a White House that “is considered irresolute on Guantánamo, lacking the force or the desire to impose a coherent policy upon the bureaucracy,” Ackerman noted the “longstanding bipartisan hostility in Congress to closing Guantánamo,” but pointed out that “transferring the 52 remaining detainees whom the 2010 government review deemed minimal risks” (a number that actually includes eight men approved for release by Periodic Review Boards) “is the least controversial aspect” of plans for dealing with the remaining 116 prisoners (ten others are facing, or have faced trials, and the remaining 54 are awaiting Periodic Review Boards — or are awaiting the outcomes of those reviews).

Cliff Sloan, the State Department’s envoy for Guantánamo closure from 2013-14, said, “For those who are approved for transfer, the laws passed by Congress permit it and we should be moving forward with those promptly. Any month where we’re not seeing significant numbers of transfers undermines the president’s policy and is unfair to the individuals affected.”

Clive Stafford Smith, the founder of the legal action charity Reprieve, and one of Shaker Aamer’s lawyers, , said, “it is time for the secretary of defense to stop playing these furtive games and put up or shut up. If there is one thing that is worse than indefinite, arbitrary detention without trial, it is indefinite, arbitrary detention without trial when 99% of the people on both sides think you should be released but one percent vetoes fairness secretly, without giving reasons, either to Shaker or to the prime minister of Great Britain.”

Below I’m also delighted to post an op-ed that Clive wrote for the Guardian on the day after this distressing news about the Pentagon’s anti-democratic obstruction of justice at Guantánamo was revealed, in which, quite correctly, he stated, “President Obama, it seems, has personally ordered Aamer’s release, and his subordinates have ignored and thwarted his order,” adding, “the contravention of the president’s orders indicates that there is a profound problem with the state of democracy in America. The military is not a democratic institution; a soldier takes an oath to follow orders. When a military officer simply chooses not to follow the clear order of the president, it is a slap in the face for the American system of government.”

The military ignores Obama’s order to release Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo

By Clive Stafford Smith, The Guardian, August 14, 2015

Recent history demonstrates that if President Barack Obama, arguably the most powerful person on planet Earth, wants to prioritize almost anything – from pardoning 46 convicted drug felons to bombing a foreign country without the consent of Congress – little can stand in his way. Why, then, is Shaker Aamer not home in London with his wife and four children?

Aamer is the last British resident to be detained without trial in Guantánamo Bay and he has never been charged with a single offense. In 2007, he was cleared for release by the Bush Administration; in 2009, six US intelligence agencies unanimously agreed that Shaker should be released. In January 2015, British Prime Minster David Cameron personally raised Shaker’s plight with President Obama, who promised that he would “prioritize” the case.

On Thursday, we came a little closer to understanding the reason that Aamer’s youngest child, Faris – who was born on Valentine’s Day 2002, the day that Aamer was rendered to the detention center at Guantánamo Bay – has never even met his father. The Guardian revealed that “the Pentagon [is] blocking Guantánamo deals to return Shaker Aamer and other cleared detainees.” President Obama, it seems, has personally ordered Aamer’s release, and his subordinates have ignored and thwarted his order.

However, Article II, Section 2 of the US Constitution provides that the “President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States”. Under Article 90 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, to disobey an order in peacetime is punishable by life in prison. If we believe the Pentagon theory that we are involved in a “Global War on Terror”, then there is an ongoing war, and the punishment for disobeying orders is death.

I certainly don’t advocate that General Martin Dempsey, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff named by the Guardian as an opponent of President Obama’s order, be shot at dawn. However, the contravention of the president’s orders indicates that there is a profound problem with the state of democracy in America. The military is not a democratic institution; a soldier takes an oath to follow orders. When a military officer simply chooses not to follow the clear order of the president, it is a slap in the face for the American system of government.

What makes General Dempsey qualified to be the ultimate arbiter of due process? It is certainly not his intimate knowledge of the prisoners who he has blackballed. I am not sure General Dempsey has ever even been to Guantánamo; I have, some 35 times. Certainly, he has never met Shaker Aamer; I have, some 35 times. If General Dempsey took the time to learn the facts, he would discover that Aamer is no more a terrorist than the general himself is. Aamer loudly protests his detention without trial; all he wants is to be back with his children in London.

I also represent the second detainee whose release Dempsey is blocking, Ahmed Abdul Aziz. He was cleared five years ago, and his transfer to Mauritania was agreed by the State Department in 2013. Aziz, too, merely wants to be back with his wife and his son.

In addition to being General Dempsey’s commander-in-chief, President Obama is a lawyer: he knows that the legal black hole that is Guantánamo is a blot on America’s record; he recognizes that the very word “Guantánamo” now acts as a recruiting sergeant for the extremists around the world. In 2004, a “Senior Defense Intelligence Agency Official” told journalist David Rose that for every detainee in Guantánamo Bay, we had spawned 10 new supporters of terrorism. More than 11 years later, sadly the multiplier is far larger.

One of the reasons that Guantánamo is such a blot on America’s reputation and such a good recruiting tool is the un-American and arbitrary detention of detainees without trial. And it is even more offensive to the rule of law for the US to to clear a prisoner for release twice, and then continue to hold him for year upon year because some military officer decides that he knows best but will not come clean in public and explain himself.

President Obama should certainly call General Dempsey into the Oval Office and read him the riot act. And though Obama is right to try to close Guantánamo Bay in general, the broader issue at stake is whether he is willing to allow the Pentagon to undermine the very essence of the US constitution. The president has given an order to the military; they need to obey it.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 7, 2015

War Is Over, Set Us Free, Say Guantánamo Prisoners; Judge Says No

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Back in March, as I explained in an article at the time, lawyers for five Afghan prisoners still held at Guantánamo wrote a letter to President Obama and other senior officials in the Obama administration, in which they sought their release, on the basis that, as the lawyers put it, “Their continued detention is illegal because the hostilities in Afghanistan, the only possible justification for detention, have ended. Therefore, these individuals should be released and repatriated or resettled immediately.” They referred to President Obama’s State of the Union Address, on January 20 this year, at which the president said, “Tonight, for the first time since 9/11, our combat mission in Afghanistan is over.”

In my article, I also mentioned a federal court filing submitted on behalf of a Yemeni prisoner, Mukhtar al-Warafi, at the end of February calling for his release for similar reasons. I stated, “One of al-Warafi’s lawyers is Brian Foster, who, with colleagues at the law firm Covington & Burling, represents prisoners accused of being involved with the Taliban as well as others accused of having some involvement with al-Qaeda. Foster said they ‘chose al-Warafi’s case as a first test because he was only ever named as a member of the Taliban, offering a clearer argument for why he should be set free now,’ as opposed to men accused of having al-Qaeda connections.”

As I also discussed recently, al-Warafi was approved for release by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force in January 2010, but had his habeas corpus petition subsequently challenged by the Justice Department, in an example of a lack of joined-up thinking within the government. Al-Warafi’s habeas petition was subsequently turned down by a judge in March 2010.

Since my article in April, another prisoner, Fayiz al-Kandari, the last Kuwaiti held at Guantánamo, also sought his release because of the end of hostilities. As the Associated Press described it in an article in June, “In a court filing, lawyers for al-Kandari wrote that ‘there is no longer a battlefield in Afghanistan in which the United States is sustaining active combat operations. Accordingly, there is no longer a basis under the international laws of war to detain’ their client.”

The detention of the Guantánamo prisoners is based on the Authorization for Use of Military Force, passed by Congress within days of the 9/11 attacks. The AUMF authorized the president to pursue anyone he regarded as being connected to the 9/11 attacks, and in June 2004, in Hamdi vs. Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court ruled that detentions based on the AUMF were legal, but only as long as “active hostilities” continued.

Looking at al-Warafi’s case as well as al-Kandari’s, the AP explained how defense lawyers have pointed out that, even prior to his State of the Union Address, President Obama “unequivocally signaled an end to the military conflict when, on Dec. 28, he declared that ‘our combat mission in Afghanistan is ending, and the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion.'”

However, as the AP put it, “the Justice Department says ‘active hostilities’ clearly persist against the Taliban and al-Qaeda, and that Obama never suggested that all military and counterterrorism operations would be coming to an end.”

In April, in a reply in al-Warafi’s case, government lawyers stated, “Simply put, the president’s statements signify a transition in United States military operations, not a cessation.”

Eugene Fidell, who teaches military justice at Yale Law School, said, “Presidents say things,” and, in the AP’s words, “recalled President George W. Bush’s celebratory Iraq War speech in 2003, delivered from the deck of an aircraft carrier under a ‘Mission Accomplished’ banner.”

“Well, the mission wasn’t accomplished,” Fidell said. “Perhaps some presidential statements of fact have an aspirational flavor.”

Steven Vladeck, a national security law professor at American University, acknowledged, however, that “[t]he lawyers for the detainees are asking the right questions. And what’s really interesting is that the government can’t quite seem to figure out its answer.” Vladeck added that “the real question is not whether the government is going to win this round, but how.” He predicted that “[t]here’s going to be some skepticism from the judges about the inconsistencies in the government’s position and its limitlessness.”

In the end, the first decision, in al-Warafi’s case, delivered on July 30, came down in the government’s favor. As the New York Times described it, Judge Royce C. Lamberth of the District Court in Washington D.C. ruled that the US military “may continue to hold a Guantánamo Bay detainee accused of being a Taliban fighter even though President Obama has repeatedly said that the United States’ war in Afghanistan has ended.”

The 14-page ruling, the Times added, “was a rare judicial attempt to resolve legal questions that may have implications for years to come — including how a war against a loose-knit organization of terrorists and their splintering, morphing allies can come to a definitive end, and who decides whether it has done so.”

Judge Lamberth, as the Times put it, “ruled that regardless of what Mr. Obama has said about the status of the war in Afghanistan, there continues to be fighting between the United States and the Taliban. As a result … the government retains the legal authority to detain enemy fighters, including Taliban members, to prevent them from returning to that fight.”

Judge Lamberth stated, “A court cannot look to political speeches alone to determine factual and legal realities merely because doing so would be easier than looking at all of the relevant evidence. The government may not always say what it means or means what it says.”

For Mukhtar al-Warafi, this must be a bitter blow, as it was Judge Lamberth who refused to grant his habeas petition back in March 2010.

As the Times explained, al-Warafi’s lawyers “argued that Mr. Obama had the power to decide when the war was over, and his public comments showed that the government’s legal authority to detain suspected Taliban prisoners had expired. The Justice Department agreed that Mr. Obama had the power to decide when it was over, but submitted a letter to the court in which Mr. Obama had said that the armed conflict in Afghanistan, including against the Taliban, continued.” In response, al-Warafi’s lawyers “said the Obama administration was trying to go back on the president’s previous pronouncements.”

Judge Lamberth, however, ruled that “both sides were wrong in saying that it was up to the president alone to say whether a war was over for legal purposes.” He said that the courts “had to independently determine whether fighting was still going on, regardless of political speech.”

The Times noted that Judge Lamberth’s reasoning “implied that someday, a court could rule that the war was over and require that detainees be freed, even if the president at that time disagreed.” However, David Remes, one of his lawyers, “expressed disappointment, in part because the existence of ‘fighting’ as triggering wartime detention powers is a lower standard than a full-blown ‘armed conflict.'”

Remes said that the ruling “seemed to endorse the idea of a limitless forever war under which the government can continue to hold men for as long as there is ‘fighting.'”

The Guardian added that Brian Foster “said the judge’s opinion amounted to a ‘rubber stamp for endless detention.'” He added that “he would review the opinion and decide whether to appeal.”

Please also see below a cross-post of an op-ed for Al-Jazeera by another Guantánamo prisoner, Moath al-Alwi (aka Muaz al-Alawi) asking, “If the war is over, why am I still here?”

If the war is over, why am I still here?

By Moath al-Alwi, Al-Jazeera, June 23, 2015

I hear the war in Afghanistan is over.

This war was supposedly the reason I remained trapped, rotting in this endless horror at Guantánamo Bay. I write this letter today to ask, if this war has ended, why am I still here? Why has nothing changed?

Amid falling bombs and mass hysteria, I fled Afghanistan for safety when the US launched its military operations in 2001. I was abducted despite never fighting against the United States, was sold into US military custody, and then imprisoned, tortured, and abused at Guantánamo since 2002 without ever being charged with a single crime.

I protest this injustice by hunger striking, refusing food and sometimes water. One of Guantánamo’s long-term hunger strikers, I am a frail man now, weighing only 96 pounds (44kg) at 5’5″ (1.68m).

Recently, my latest strike surpassed its second year. My health is deteriorating rapidly, but my intention to continue my strike is steadfast. I do not want to kill myself. My religion prohibits suicide. But despite daily bouts of violent vomiting and sharp pain, I will not eat or drink to peacefully protest against the injustice of this place. My protest is the one form of control I have of my own life and I vow to continue it until I am free.

I remain on lockdown alone in my cell 22 hours a day. Despite my condition, prison authorities unleash an entire riot squad of six giant guards to forcibly extract me from my cell, restrain me onto a chair and brutally force-feed me daily. They push a thick tube down my nose until I bleed, after which I vomit.

This gruesome procedure may not be written about so much any more, but it remains my everyday reality. It is painful. And it is bewildering. How can I possibly resist anyone, let alone these men? Hunger striking is a form of peaceful and civil disobedience. It is not a crime. So why am I being punished? Why not humanely tube-feed me instead?

My time here has been ridden with unanswered questions. Two years ago, as I attempted to pray, a sudden raid was ordered and a guard deliberately shot me without warning or provocation. Once again, I was not resisting. So why did he shoot? My clothes, torn, were soaked in my own blood. I want the government to ask the guard who shot me to account for his actions.

I began to wonder if shooting without any provocation is legal in the US. But now I realise that US police officers get away with ruthlessly killing black people all the time.

I wonder now if the US follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?

For us at Guantánamo, this place is not fit for any living, breathing, human being. The US seems to want to smother us, to kill us slowly as we are left in a vacuum of uncertainty wondering if we will ever be free.

I have lived the past 13 years in this despair, at the cost of my dignity, paying the price for the US government’s political theatre. Meanwhile, little has changed for the 122 men [note: now 116] remaining at Guantánamo.

The world may turn a blind eye and find this number small. But for each of us here, the cost of our indefinite and unfair imprisonment is beyond immeasurable. Our families have lost fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons to this hell on earth. Many of us have unnecessarily lost over a decade of our already short time in this world, yearning to be free again.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Photos: Jeremy Corbyn at CND’s Hiroshima Day 70th Anniversary Ceremony in Tavistock Square

See my photos of the Hiroshima Day 70th Anniversary Ceremony in London on Flickr here!

Yesterday, August 6, was the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, when, for the first time ever, an atomic bomb — dropped by the US — was used on a largely civilian population. I have been an implacable pacifist, and an opponent of nuclear weapons (and nuclear power), all my life, and a particularly important staging post in my development was when I was ten years old, and I watched the whole of the groundbreaking ITV series, ‘The World at War.’

So yesterday I was at Tavistock Square, with hundreds of other opponents of nuclear weapons, for CND‘s Hiroshima Day 70th Anniversary Ceremony, where speakers included the man of the moment, Jeremy Corbyn, who is standing for the leadership of the Labour Party, and is drawing huge crowds at meetings around the country, for two reasons — he presents a compelling anti-austerity point of view, which a significant number of people are crying out for, and he is genuine and honest and not distracted by the politics of personality, when it is the issues — the common good, fighting inequality and caring for our world and each other — that are most important. For just £3 you can become a registered Labour supporter and vote in the leadership election. You have to register by August 12th, ballots will be sent out on the 14th and must be completed, by post or online, by September 10.

I am pleased to have been involved with Jeremy though his membership of the Shaker Aamer Parliamentary Group, calling for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and before he decided to stand in the leadership contest, he was one of four MPs who made up a delegation to Washington D.C., where they met Senators including John McCain and Dianne Feinstein, and also met with representatives of the Obama administration.

Yesterday, however, Jeremy was at Tavistock Square to remember Hiroshima, and to continue the campaigning against the existence of nuclear weapons that, as he said on Twitter the night before, he first took up at the age of 15. I saw him speak — as powerfully as ever — and I also saw the author A. L. Kennedy, who read some powerful poems, and Sheila Triggs of WILPF (the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom), which was founded in 1915. The compere was Bruce Kent, and other speakers included Baroness Jenny Jones of the Green Party.

A video of Jeremy’s speech is below, via YouTube:

Remembering what happened on August 6, 1945, the Guardian explained:

The bomb exploded 580 metres (2,000ft) above a T-shaped bridge at the junction of the Honkawa and Motoyasu rivers, unleashing a blinding flash followed by a deafening boom.

About 70,000 people died instantly in the blast or from the firestorms that raged moments later. The death toll would rise to about 140,000 by the end of 1945. The explosion, equal to 12,000 to 15,000 tonnes of TNT, destroyed more than two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings across five sq miles.

Within 45 minutes of the attack, nuclear fallout mixed with ash and smoke from the firestorms to create a radioactive black rain that soaked survivors and did not abate until the fires began to burn themselves out in the evening.

As people staggered among the dead and dying in search of water and medical treatment, news began to spread to the capital, Tokyo, that something unspeakable had occurred in Hiroshima.

But wartime leaders did not receive confirmation that the city had been destroyed by a nuclear weapon until the following day, when the US president, Harry S Truman, said: “Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima. It is an atomic bomb.”

I also recommend the recollections of Sunao Tsuboi, “a retired school principal who has travelled the world to warn of the horrors of nuclear warfare,” who was a 20-year old university student in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The Guardian published his recollections in the run-up to the anniversary, including the following passages:

Tsuboi remembers hearing a loud bang, then being blown into the air and landing 10 metres away. He regained consciousness to find he had been burned over most of his body, his shirtsleeves and trouser legs ripped off by the force of the blast.

“My arms were badly burned and there seemed to be something dripping from my fingertips,” said Tsuboi, who is co-chair of Nihon Hidankyo, a nationwide organisation of atomic and hydrogen bomb sufferers.

“My back was incredibly painful, but I had no idea what had just happened. I assumed I had been close to a very large conventional bomb. I had no idea it was a nuclear bomb and that I’d been exposed to radiation. There was so much smoke in the air that you could barely see 100 metres ahead, but what I did see convinced me that I had entered a living hell on earth.

“There were people crying out for help, calling after members of their family. I saw a schoolgirl with her eye hanging out of its socket. People looked like ghosts, bleeding and trying to walk before collapsing. Some had lost limbs.

“There were charred bodies everywhere, including in the river. I looked down and saw a man clutching a hole in his stomach, trying to stop his organs from spilling out. The smell of burning flesh was overpowering.”

He was taken to a hospital, where he remained unconscious for over a month. By the time he came to, a defeated Japan was under the control of the US-led allied occupation.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 5, 2015

Tariq Ba Odah, Hunger Strikes, and Why the Obama Administration Must Stop Challenging Guantánamo Prisoners in Court

In June, I wrote an article, “Skeletal, 75-Pound Guantánamo Hunger Striker Tariq Ba Odah Seeks Release; Medical Experts Fear For His Life,” about the desperate plight of Tariq Ba Odah, a Guantánamo prisoner who has been on a hunger strike since 2007 and is at risk of death. His weight has dropped to just 74.5 pounds, and yet the government does not even claim that it wants to continue holding him. Over five and a half years ago, in January 2010, the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established when he took office in 2009 to review the cases of all the prisoners still held at that time, concluded that he should no longer be held.

In June, I wrote an article, “Skeletal, 75-Pound Guantánamo Hunger Striker Tariq Ba Odah Seeks Release; Medical Experts Fear For His Life,” about the desperate plight of Tariq Ba Odah, a Guantánamo prisoner who has been on a hunger strike since 2007 and is at risk of death. His weight has dropped to just 74.5 pounds, and yet the government does not even claim that it wants to continue holding him. Over five and a half years ago, in January 2010, the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established when he took office in 2009 to review the cases of all the prisoners still held at that time, concluded that he should no longer be held.

The task force approved 156 men for release, although Tariq was one of 30 placed in a category invented by the task force — “conditional detention,” made dependent on a perception that the security situation in Yemen had improved or “an appropriate rehabilitation program or third- country resettlement option becomes available,” as his lawyers described it.

Collectively, the whole of the US establishment has — with one exception — refused to repatriate any Yemenis approved for release since January 2010 (after a foiled terror plot was revealed to have been hatched in Yemen), although, since last November, the administration has been finding third countries willing to offer new homes to Yemenis approve for transfer — in part became of persistent pressure from campaigning groups. 18 Yemenis have so far been found homes in third countries — in Georgia, Slovakia, Kazakhstan, Estonia and Oman — so all that now ought to prevent Tariq Ba Odah’s release is if the US government proves unable to find a third country prepared to offer him a new home.

However, lawyers in the Justice Department disagree. In June, Tariq’s lawyers asked the District Court to reinstate his habeas corpus petition, which he previously launched in September 2006, but dropped in March 2014, because, as his lawyers put it, “in his already weakened state, Mr. Ba Odah could not effectively participate in mounting a defense to the government’s allegations against him.”

Tariq’s request provided a perfect opportunity for the government to avoid a potential death at Guantánamo of someone they no longer want to hold, but his lawyers at the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights have, in the last week, stated that lawyers for the government, in the Civil Division of the Justice Department, have announced their intention to challenge Tariq’s habeas corpus petition.

The Civil Division of the Justice Department has been a key player in maintaining the existence of Guantánamo throughout its long and unjustifiable history. The Civil Division’s lawyers have persistently made life as difficult as possible for lawyers attempting to visit their clients at Guantánamo, and have fought tooth and nail against every single habeas petition submitted by the prisoners, with just one exception — the severely ill Sudanese prisoners Ibrahim Idris, whose petition was granted unopposed in 2013.

Disgracefully, the Justice Department lawyers have repeatedly challenged habeas petitions submitted by prisoners whose release has already been approved by the Guantánamo Review Task Force, as in Tariq’s case, and, just as disgracefully, no one in the mainstream US media has challenged them — until now.

As I explained back in October 2013, when Idris’ habeas petition was granted unopposed:

What is particularly noteworthy about the Justice Department’s decision in the case of Ibrahim Idris is that it marks the first time that the Civil Division lawyers — those responsible for dealing with the prisoners’ habeas petitions — have backed down. In place since the days of George W. Bush, the lawyers have vigorously contested every petition as though the fate of the United States depended on it. This may make sense given the adversarial nature of the law, but what doesn’t make sense is that petitions have been fought even when the men in question have been cleared for release by President Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force.

I am unable to explain why there has been no cross-referencing of cases between the task force (which involved officials from the Justice Department) and the Civil Division of the DoJ, or why Attorney General Eric Holder has maintained the status quo, and no other senior official, up to and including the President, has acted to address this troubling lack of joined-up thinking.

Prisoners subjected to this lack of joined-up thinking (see my definitive habeas list here for further details, and the full prisoner list here) include Saeed Hatim, a Yemeni whose habeas petition was granted in December 2009. He was then approved for release by the task force, but the government appealed his successful habeas petition, and the court of appeals — heavily biased in favor of ongoing detention — vacated his successful petition in February 2011. In February 2010, judges turned down the habeas petitions of two other Yemenis approved for release by the task force, Suleiman al-Nahdi and Fahmi al-Assani, a process repeated in March 2010 in the case of another Yemeni, Mukhtar al-Warafi.

In July 2010, Hussein Almerfedi, another Yemeni approved for release by the task force, had his habeas petition granted, but that ruling was overturned on appeal in June 2011. Hussein was finally freed in Slovakia in November 2014, but Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, another Yemeni, was not so fortunate. Approved for release by the task force, he had his habeas petition granted in July 2010, but it was overturned on appeal in October 2011. In September 2012, Latif died at Guantánamo, and, as I explained at the time, all three branches of the government bore responsibility for his death.

Also in July 2010, Abdul Rahman Sulayman, a Yemeni approved for release by the task force (but placed in the “conditional detention” category) has his habeas petition denied, as did Shawali Khan, an Afghan, in September 2010. Khan was finally freed in December 2014. In October 2010, Tawfiq al-Bihani, another Yemeni, had his habeas petition turned down, even though he had been approved for release by the task force (and had also been placed in the “conditional detention” category).

In August 2011, Fadel Hentif (aka Fadil Hintif), another Yemeni approved for release by the task force, had his habeas petition turned down, although he was finally released in Oman in January 2015. The same thing happened in October 2011 with Abdul Qader Ahmed Hussein (aka Abdul Qader Ahmed Hussein, Ahmed Abdul Qader), who was finally released in Estonia, also in January 2015 — and please see here for a powerful dissenting opinion by Judge Harry T. Edwards after Hussein’s appeal was turned down in June 2013. By 2012, lawyers for the prisoners more or less gave up on the habeas petitions they had fought for for so long, because of the appeals court’s scandalous rewriting of the rules, which effectively killed habeas corpus for the prisoners, and also because of the Supreme Court’s unwillingness to intervene.

Finally, however, in an editorial in July 29, the New York Times has provided a high-level call for the Justice Department to police itself in the name of justice for the men held at Guantánamo. As the editors note, following the example of Tariq Ba Odah’s case, President Obama could “instruct the Justice Department not to stand in the way of low-risk inmates who are actively seeking their release through habeas corpus petitions,” so that “[j]udges could approve release without having to rule on the merits of each case or rule on the government’s detention authority.”

The editors also note that there are currently around ten men with active habeas corpus petitions, and that instructing the Civil Division not to challenge the habeas petition of men already approved for transfer out of Guantánamo “could expedite the release of several of the 52 men who have been cleared for release,” and “would take the country one step closer to correcting a legal travesty that began more than 13 years ago,” when the prison at Guantánamo Bay opened.

I hope the administration pays attention to the Times‘ editors’ proposal, which would bypass the cumbersome need for the defense secretary — currently dragging his heels on Guantánamo — to provide 30 days’ notice to Congress prior to any prisoner release, and to certify to lawmakers that every effort to mitigate the potential risk posed by a released prisoner has been taken. I’d also like to see the administration revisit some of those cases when the Guantánamo Review Task Force’s decisions were ignored by the Justice Department (Saeed Hatim, Suleiman al-Nahdi, Fahmi al-Assani, Mukhtar al-Warafi, Abdul Rahman Sulayman and Tawfiq al-Bihani) as well as other decisions taken before the task force issued its report, of prisoners whose habeas petitions were turn down, but who were then approved for release by the task force.

The first of these is Adham Ali Awad, a Yemeni whose habeas petition was turned down in August 2009. He was then approved for release by the task force (and placed in the “conditional detention” category) in January 2010, but he had his appeal denied in June 2010. Also in August 2009, Mohammed al-Adahi, another Yemeni, had his habeas petition granted, but that was overturned on appeal in July 2010, six months after the task force recommended his release (and also placed him in the “conditional detention” category).

Below I’m cross-posting the New York Times editorial, and also, for those who missed it, an article in Rolling Stone about Tariq, written by his lawyer, Omar Farah, a tireless campaigner for justice whom I have met on many occasions, and with whom I spoke at an event in New York in January.

While Guantánamo Logjam Endures, Some Prisoners Could Be Freed

New York Times editorial, July 29, 2015

American national security officials concluded more than five years ago that Tariq Ba Odah, a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, should be released because he doesn’t pose a major risk. Mr. Ba Odah, a Yemeni citizen who has been on a hunger strike since February 2007 and is subject to forced feeding, is emaciated. Fearing that he could starve to death in the near future, his lawyers recently filed a petition challenging his detention.

Senselessly, the Department of Justice has said it will fight it, according to Mr. Ba Odah’s lawyer.

The Obama administration’s plan to shut down the prison at Guantánamo Bay has been hamstrung by Republican lawmakers and by President Obama’s current and former secretaries of defense, who have been slow to sign off on individual releases, as required by law.

While Mr. Obama’s aides wrestle with these political and bureaucratic logjams, cases like that of Mr. Ba Odah and some other inmates present the president with options. He may instruct the Justice Department not to stand in the way of low-risk inmates who are actively seeking their release through habeas corpus petitions. Judges could approve release without having to rule on the merits of each case or rule on the government’s detention authority.

That could expedite the release of several of the 52 men who have been cleared for release. It would take the country one step closer to correcting a legal travesty that began more than 13 years ago when the first prisoners arrived at the prison President George W. Bush created for the particular purpose of evading American constitutional and moral constraints. Of the 116 remaining prisoners at Guantánamo, approximately 10 have active habeas corpus petitions.

Mr. Ba Odah, who was never charged with a crime, began refusing to eat more than eight years ago. Since then, military personnel have fed him forcefully by inserting a liquid formula through his nostrils. Medical experts who have studied his case say Mr. Ba Odah, whose weight dropped to 74 pounds earlier this year from 140 pounds in 2007, “is gravely malnourished and in danger of catastrophic physical and neurological impairment and even death.”

If he were to die in custody, Mr. Ba Odah would become the first inmate at Guantánamo Bay to die from malnutrition. That would be a shameful outcome that Mr. Obama can easily prevent.

Using habeas petitions to release a handful of inmates in the near future would be sensible. Significantly reducing the population at Guantánamo, though, will require Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter to start authorizing transfers. His predecessor, Chuck Hagel, was forced to resign in large part because White House officials felt he was being too slow to authorize the release of detainees. But Mr. Carter, who has been on the job since February, has yet to authorize new proposed transfers. Under current law he is required to assert to Congress that the United States has taken adequate measures to mitigate the risks posed by the release of any inmate from Guantánamo.

There is a practical need for Mr. Carter to stop dragging his feet: Several members of Congress are attempting to impose even stricter restrictions on inmates’ release than currently exist. Lawmakers are in the process of reconciling the House and Senate versions of the annual National Defense Authorization Act. The Senate version retains the current restrictions, which bar the transfer of prisoners to American soil. The House bill includes provisions that would make it practically impossible to release new inmates to any destination.

The lawmakers’ indefensible overreach on detainee policy was aptly described by the retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens during a speech he delivered in May. “These onerous provisions have hindered the president’s ability to close Guantánamo, make no sense, and have no precedent in our history,” Justice Stevens said. “Congress’s actions are even more irrational than the detention of Japanese Americans during World War II.”

Tariq Ba Odah’s Eight-Year Hunger Strike at Guantánamo Bay

By Omar Farah, Rolling Stone, July 6, 2015

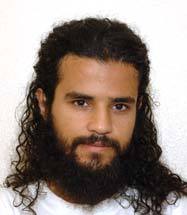

Tariq Ba Odah would be a slight man, even if he were willing to eat. His shoulders are barely wide enough to keep his orange prison uniform in place. His wrists are childlike and his hands delicate, veins visible all the way to the ends of his fingers. When his arm is straightened, he can almost touch the tip of his pinky to his thumb around his own bicep. The combination of his raised cheekbones and beard cast a shadow down the side of his face. His eyes and nose are naturally large, though they take on particular prominence now that his weight has fallen under 80 pounds. Ba Odah’s curly black hair, which he keeps shoulder-length, does little to fill out his profile. The office chairs in the cells in Camp Echo, where Guantánamo prisoners and attorneys typically meet, appear to swallow Ba Odah up. Sores plague him. The pain in his stomach and back cause him to shift in place moment to moment. All of this gives Ba Odah the appearance of, as a fellow prisoner put it, a bird about to take flight. But Ba Odah has been caged at Guantánamo for more than 13 years, despite being cleared for release by the nation’s top national security agencies. He is 36 years old.

Ba Odah arrived at Guantánamo like so many other prisoners who have passed through its wire gates. For reasons he does not understand, he says he was arrested by local police in Pakistan and handed over to American forces. A stubborn myth about the men at Guantánamo is that at some point they were all squared off against U.S. soldiers with guns drawn, and were captured and shipped off to Guantánamo to neutralize the threat they posed. The well-documented but little known reality is that following its invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the U.S. military ran a slipshod, bounty-based dragnet that ensnared hundreds of men and boys whose worst crime was being at the wrong place at the wrong time. Ba Odah says he was among them – sold into U.S. custody and then rendered to Guantánamo at roughly 23 years old. The trip was a harbinger of what lay ahead. For two days on the transport plane he says he was drugged, and his hands, legs and waist were tied “to the point of feeling that his body would be ripped apart.” A rotten black cover was placed over his head. He says he was “dying a thousand times every moment because of the inability to breathe.”

Today at Guantánamo, Ba Odah is what is known as a “long-term” hunger striker. Ba Odah has not eaten – not voluntarily, at least – since February of 2007. As a result, he is force-fed, usually in the morning and again in the evening. Guards remove Ba Odah from his cell, several at a time in protective gear, strap him to a restraint chair, and medical staff force a liquid supplement through his nose and into his stomach. “Waterboarding,” Ba Odah calls it, both for the obvious torture analogy and because, at times, it has caused him to urinate and vomit.

I traveled to Guantánamo to see Ba Odah in March. I met with him again on April 21. Ba Odah had recently passed the eighth anniversary of his hunger strike, but he was not in the mood to reflect: “I don’t feel the days anymore.” Ba Odah doesn’t feel much of anything anymore. “My body gets so numb; no sensation,” he said, rapping his knuckles on the arm of his chair to illustrate the point. Apparently, this is a symptom of starvation. And with military doctors saying Ba Odah is now only 56 percent of his ideal body weight, there is no doubt he is starving. The Defense Department’s force-feeding regimen is not working. When Ba Odah lifted his prison smock, I had to look down. All I managed to write in my legal pad was “does not look like body of human; every bone visible.” Imagine liberation photos of Holocaust survivors, and you will have a sense of what I saw. Ba Odah sat back in his chair and said, “My life is not like it was. This is the hardest I have ever had it.”

My visit in April was the most recent in a series of meetings that began five years ago. By the time Ba Odah and I first met face-to-face in 2010, I had already been his lawyer for two years. Agreeing to introduce himself to me in person was a decision Ba Odah weighed carefully. Guantánamo has taught him to be leery of leaving his cell. What follows is rarely pleasant: over the years, he has endured more humiliating interrogations than he can remember; when the prison administration rotates him to a new cellblock, typically it is to make his confinement more isolative. Even visits to the prison clinic are coercive; Ba Odah complains of an array of physical ailments, from a collapsing nostril to bloody stools, but says simple medical assistance is withheld to compel him to abandon his strike. Worse still, in recent years, the prison administration implemented pretextual searches of the prisoners’ genital areas whenever they enter or leave the cellblock. So it was understandable that Ba Odah consistently declined my meeting requests. Indeed, much of our initial contact was through “refusal” notes – handwritten messages attorneys send to persuade Guantánamo prisoners to attend a scheduled legal meeting.

No matter how challenging attending meetings may be, it must still seem odd to those unfamiliar with Guantánamo that someone enduring what amounts to an indefinite sentence without ever being charged or tried would refuse the assistance of counsel. But Ba Odah has seen well-meaning lawyers come and go at Guantánamo for a decade, while little has changed for him. As he observes, only the cells change, becoming rustier and more decrepit by the year – a visual reminder of the time that has elapsed.

There is no shortage of blame to go around for Guantánamo’s continued operation. My March trip to the prison happened to coincide with Tom Cotton’s tightly scripted media tour – one would have thought the freshman senator would visit Guantánamo before his “rot in hell” stunt at the Senate Armed Services Committee hearing in February. My visit in April followed the launch of Marco Rubio’s presidential bid, during which he called for Guantánamo’s expansion and declared the six prisoners recently freed to Uruguay, each unanimously cleared by multiple national security agencies, “a danger … for our country and the world.” Meanwhile, Republican senators are seizing on ISIL’s bloodthirst to ram through legislation intended to halt all Guantánamo releases indefinitely. Yes, fearmongering around Guantánamo is old news, but the stakes remain high – higher now than ever. With less than two years left in the White House, President Obama now says he failed to close Guantánamo only because of politics, rhetoric and fear. It is a haunting admission considering the suffering Ba Odah so easily could have been spared.

Unsurprisingly, in Ba Odah’s view, lawmakers, the courts and the president are all part of the same system that keeps him locked up and far from his family. To make his point, Ba Odah often gestures to the lock on the cell door where we meet and says, “The men who brought me here on the first day, those are the only ones with the power to let me out when it’s my last.” I am hard-pressed to disagree. But, surely, as the person with ultimate power over Ba Odah’s fate, President Obama bears unique responsibility for the fact that today, Ba Odah remains in isolation at Guantánamo, bracing himself for his next feeding.

Ba Odah believes the Obama administration is consistent only in that it never does what it says it will. Upon taking office, President Obama vowed not only to close Guantánamo within a year, but also to ensure living standards for the prisoners were compliant with the Geneva Conventions. Yet, in some objectively measurable ways, Ba Odah’s detention was more tolerable before President Obama took office.

Ba Odah says it was not until May 2009 that he was transferred to Guantánamo’s notorious Camp 5, where prisoners are held in isolation cells. Almost without interruption, Ba Odah has been committed to solitary confinement ever since. “Days go by and I do not speak to a soul,” Ba Odah said during a March 2012 meeting. And the little recreation time he is allowed – sometimes just two hours per day – has been scheduled during hours not customarily devoted to physical fitness. “As I have already mentioned to you,” Ba Odah wrote to me in a letter, “I’ve been spending 24 hours a day inside the cell for a long period of time, and that is due to the myriad problems I have been facing. The prison officials scheduled my two-hour recreational walk for three o’clock in the morning. The purpose of such scheduling is to increase the pressure on me. At that hour, I will still be on my own, even in the rec area.” In response, Ba Odah has also gone on “no wash” protests, once refusing to leave his cell, shower or cut his nails for four months. “I looked like I crawled out of a grave. Finally the military asked me to stop and gave me back my full rec privileges.” The sad reality is that, whether alone or not, Ba Odah is often too weak to take advantage of the little sunlight he is permitted.

For allowing his Department of Defense to mismanage Guantánamo, President Obama should come in for withering criticism. Of course, even if Guantánamo were the “state-of-the-art” detention facility it is often said to be, it would do little to ameliorate Ba Odah’s suffering. Like most at Guantánamo, he is tormented by the rational fear that, after more than a decade, his cell may one day become his coffin. Nine Guantánamo prisoners have already met that fate. The failing of the judiciary and Congress notwithstanding, the president alone is empowered to avert such a disaster. From November 2014 through January 2015 – in just three months – he freed 27 men. That was more than in the prior three years combined. The White House wields remarkable power to effect transfers when it chooses to do so. Yet, all too often, it shows little interest in martialing that power.

Though Ba Odah does not despair, he is under no illusions about the Gordian knot ensnaring him at Guantánamo. No matter the occupant of the Oval Office, the partisan makeup of Congress, the base-commander presiding or the guards on duty, his detention is a game with a predetermined outcome: the prisoners lose until someone more powerful spares them. In the interim, they pay a heavy price. As Ba Odah puts it: “Freedom should be much more precious for the human being than all the desires on earth.” Detention, therefore, is brutal; indefinite detention, mercilessly so.

At Guantánamo, however, indefinite detention is compounded by the indignity inherent in a system that seems to encourage prisoners’ participation only to mock them. Why else create elaborate administrative and judicial processes – Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRT), Administrative Review Boards, Periodic Review Boards, Inter-Agency Task Force reviews and habeas corpus hearings – that after 13 years still have so little to show for themselves? Ba Odah, like so many others at Guantánamo, sees it as little more than the elevation of process over justice. The purpose, he says, is to pacify a prison population enduring unspeakable suffering. This is why he easily draws comparisons to the institution of slavery. “I was arrested on the second day of Eid Al-Fitr,” he writes, “then sold into the United States’ 21st century slavery market. As far as I am concerned, all of this pressure, humiliation, limitless injustice have been solely aimed at breaking me and breaking my brothers so that they could manipulate us … and plant in us despair and mentally enslave us just like they have physically enslaved those before us.”

Ba Odah finds redemption in protest, one organized around the principle of non-participation. Ba Odah refused to submit to a CSRT – the sham tribunals established by the Bush administration to determine who, among the hundreds of men then at Guantánamo, were “enemy combatants.” Ba Odah was similarly reluctant (and, in any event, physically unfit) to litigate his habeas petition. And, as I recounted, from 2008 until 2010, he would not even sit down with his own lawyer. It goes without saying, however, that Ba Odah’s refusal to eat is the most uncompromising form of resistance through non-participation. “I tell them again and again that I don’t want any food from them … I just don’t want it. All I want is for them leave us alone, lingering in these cells. They want me to eat, but first I have to be subjected to humiliation … The provocation is never-ending.” Therefore, Ba Odah says, his hunger strike will never end. “My method of delivering my message is through hunger strike. You can cut me to pieces, but I will not break it. I will stop on one of two conditions: I die, or I am freed and allowed to return to my family.”

Ba Odah’s discipline is humbling. His typical day is “split between praying, reading Qur’an…and contemplating memories of the past.” Sometimes he will practice walking in his cell for exercise, “three steps forward and three backwards.” The monotony is interrupted only when guards arrive to force-feed him. Ba Odah has explained that he views these as moments when his will is tested against the guards’. All too often discussion of force-feeding fails to go beyond the shocking physical details. That is understandable. According to Ba Odah, violently force-feeding prisoners has been the Department of Defense’s preferred approach to breaking strikes. Ba Odah’s descriptions of feeding sessions in 2006 and 2007 are grisly: “I was tortured with the restraining chair when they were filling my belly with two packs of Ensure. The doctors would introduce a 14 size tube with a metal end inside my nose to reach my stomach and sometimes my lungs, and when they would take it out it would be filled with blood.” Yet, for Ba Odah, hunger striking is an expression of his vitality. The physical pain, therefore, pales in comparison to the psychological trauma of having the very jailors responsible for his ordeal overbear his will in such an intimate way.

Though powerless to prevent the feedings, Ba Odah nonetheless takes pride in his fortitude. He believes he has accomplished a rare feat that, while a far cry from actual freedom, is profoundly liberating. As in any detention setting, much of the prison administration’s control at Guantánamo comes from providing (and depriving) prisoners of “comfort items” – books, recreational time, communal living assignments, anything that makes imprisonment more tolerable. Through his hunger strike, however, Ba Odah has removed the ultimate mechanism of leverage. In an environment as hostile as Guantánamo, for Ba Odah, even the primal drive to eat is a vulnerability to be conquered. He explained in a series of letters in 2013: “My body has become frail and weak, but spiritually I feel that I am a thousand times stronger than I was before. It has been seven years since I have tasted food.” He wrote later that “even the pungent smell that used to stay on my fingers after eating” is a lost memory. “I have prevailed over man’s innate weakness towards food and drink. I feel honored and proud because I sacrificed food and drink for the sake of my freedom.” By his own definition, Ba Odah has prevailed, and yet that victory has surely taken its toll.

During one of our meetings in 2014, Ba Odah looked particularly weary. His physical deterioration is the predictable result of his protest, but it is no less unsettling. We talked for a little while about how he is holding up. I try not to dwell on the subject, however. Ba Odah chose this course with eyes open; it is arduous enough without worrisome questioning. In any case, he knows all too well how he has been transformed. Other than the occasional wry smile, his face recalls a death mask more than that of a man in his thirties. As Ba Odah writes, “one day, I looked at my face in the mirror and was shocked; I would say more saddened. I felt the mirror was looking at me [and] asking if that was really me.” During this particular meeting, Ba Odah shared more than he usually does about how it feels to be bed-ridden in a filthy cell, carried away by force to be fed with tubes. He wondered openly how much more he will have to endure, but soon pivoted: “I am fine; deep inside, I feel fine. If I accepted all this without protest, that would destroy me.”

I had heard variations on that reassuring theme before, and yet, witnessing him persevere through this advanced stage of his strike, I found myself fixating on his physical condition: His eyes were more sunken than usual. His hands shook more noticeably. It seemed as though he could have slid his ankle out of the shackle in the floor if he had tried.

Back in my Guantánamo housing facility after our meeting, I returned to some of Ba Odah’s letters to remind myself why Guantánamo provokes in him such fierce resistance. There are many clues in the way Ba Odah describes his life before Guantánamo:

1978 is my year of birth; but my real birth has not come yet. I have been waiting for it for 11 years. My place of birth is the Shabwah district of Yemen. I left Shabwah when I was one year old and spent my entire life in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. I am the middle child. My mother and father were kind parents in a simple family untouched by typical familial problems. All that my father cared about was how to ensure happy and peaceful living for his family by providing us with education. Regarding my loving mother, she was and remains smiling all the time. I do not recall a day when she was harsh to me. We lived a wonderful family life, but all this changed since my capture …

My 11 years of time spent in solitary confinement is trying to kill the 11 years of childhood I spent in Wadi Jamilah in Saudi Arabia. Now, I live on just the imagination of my wonderful childhood …

At the moment when I am released, I would pray and kneel twice to Allah for the blessing of freedom, then go to my mother and hug her. As for my father, my chance to serve him is now gone because he passed away.

Ba Odah’s suffering is as unnecessary as it is unforgivable. He was cleared for release more than five years ago. Virtually no one disputes at this point whether he ought to be freed. And it is possible that those men Ba Odah describes, the ones who brought him to Guantánamo on the first day, will, at long last, come to release him. Perhaps even one day soon. In the meantime, Ba Odah has taken to scrawling the word “homesick” on the walls of his cell.

This article was adapted from the essay “Nourishing Resistance: Tariq Ba Odah’s 8-Year Hunger Strike at Guantánamo Bay” by Omar Farah, which appears in Obama’s Guantánamo: Stories from an Enduring Prison, edited by Jonathan Hafetz, to be published in June 2016 by NYU Press.

Note: See more of Matt Daloisio’s photos of Torture Awareness Week in Washington D.C., in June 2015, here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 3, 2015

Does President Obama Still Have a Plan for Closing Guantánamo?

Recently, there was a brief flurry of media interest in Guantánamo after the New York Times published an article by Charlie Savage entitled, “Obama’s Plan for Guantánamo Is Seen Faltering.”

Recently, there was a brief flurry of media interest in Guantánamo after the New York Times published an article by Charlie Savage entitled, “Obama’s Plan for Guantánamo Is Seen Faltering.”