Andy Worthington's Blog, page 91

September 7, 2015

Quarterly Fundraiser: Seeking $3500 (£2300) for My Guantánamo Work

Please support my work!

Please support my work!

Dear friends and supporters,

Every three months, I ask you, if you can, to make a donation to support my work on Guantánamo and related issues — accountability for torture, for example, and the We Stand With Shaker campaign, the specific campaign to free Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in Guantánamo, which I launched last November with the activist Joanne MacInnes. I’m hoping to raise $3,500 (£2,300) for the next three months, which is just $270 (£180) a week for my constant advocacy and campaigning on behalf of the Guantánamo prisoners.

As my work is primarily reader-funded (I receive no outside funding for this website, or for my work on the We Stand With Shaker campaign), any amount will be gratefully received, whether it is $25, $100 or $500 — or any amount in any other currency (£15, £60 or £300, for example). PayPal will convert any currency you pay into dollars.

If you can help out at all, please click on the “Donate” button above to donate via PayPal (and I should add that you don’t need to be a PayPal member to use PayPal).

You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make This Recurring (Monthly),” and if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated. If you make a recurring payment of at least $15 a month, or if you make a one-off donation of $200 or more, I’ll send you a free copy of my band The Four Fathers’ debut album, ‘Love and War’, on CD. The album includes six original songs of mine, including ‘Song for Shaker Aamer’, featured in the campaign video for We Stand With Shaker, and ’81 Million Dollars’, about the US torture program.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (address here — scroll down to the bottom of the page), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send cash from anywhere else in the world, that’s also an option. Please note, however, that foreign checks are no longer accepted at UK banks — only electronic transfers. Do, however, contact me if you’d like to support me by paying directly into my account.

It is now ten years since I first began researching the stories of the prisoners held at Guantánamo, and back in September 2005 all that was available were the scattered accounts of prisoners already released, a few accounts that had emerged from within the prison, via the men’s lawyers, who had begun visiting them at the start of the year, and two speculative lists of who might be held, compiled by the Washington Post and the British NGO Cageprisoners.

I spent some time searching online for every scrap of information about the prisoners, and began compiling a list of my own, but it was another six months until I began researching and writing about Guantánamo on a full-time basis, when the Pentagon lost a lawsuit and was obliged to release 8,000 pages of documents about the prisoners, which I then analyzed in depth for my book The Guantánamo Files.

Ten years on, and sadly there is no sign that the closure of Guantánamo, promised nearly five years and eight months ago by President Obama, will happen before he leaves office in January 2017. His administration is looking at ways to move dozens of prisoners to the US mainland so that Guantánamo itself can be closed, but he faces opposition in Congress, and, of the 116 men still held, he is still holding 52 men who have been approved for release — most since 2009 — and holding them year after year is completely unacceptable.

With your financial support, I will continue to work towards the closure of Guantánamo, conducting research, writing articles and opinion pieces and trying to come up with new initiatives to help to get the prison closed. It remains a potent icon of the injustice that was shamefully implemented by the Bush administration, with compete disdain for domestic and international laws and treaties regarding the treatment of prisoners, and as long as it remains open it ought to be a source of undying shame for everyone responsible for its continued existence.

As I have often mentioned, and will continue to do so, President Obama is in charge of a prison where men continue to be held indefinitely without charge or trial, which is unacceptable in any country that claims to respect the rule of law. The prison should never have been opened, and must be closed as soon as possible.

With thanks, as ever, for your interest in my work. I honestly couldn’t do what I do without your help, and I will be very grateful if you can make any kind of donation to support me.

Andy Worthington

London

September 7, 2015

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign.

September 6, 2015

Life After Guantánamo: Attorney Tells the Story of a Father and Son Freed, But Separated By 1,850 Miles

Back in 2006, when I began working full-time on Guantánamo, researching the stories of the men held there for my book The Guantánamo Files, which was published in September 2007, the main research I undertook involved a detailed analysis of 8,000 pages of documents relating to the prisoners that had been released in 2006 as a result of freedom of information submissions and federal lawsuits submitted by the Associated Press.

Back in 2006, when I began working full-time on Guantánamo, researching the stories of the men held there for my book The Guantánamo Files, which was published in September 2007, the main research I undertook involved a detailed analysis of 8,000 pages of documents relating to the prisoners that had been released in 2006 as a result of freedom of information submissions and federal lawsuits submitted by the Associated Press.

The documents consisted primarily of unclassified allegations against the prisoners and transcripts of various review processes — the Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRTs) and Administrative Review Boards (ARBs) — that had been conducted from 2004 onwards, purportedly to establish the status of the prisoners, although these processes were so one-sided and what passed for evidence was generally so poor that, as the AP put it, all the transcripts generally revealed about the prisoners was “the often vague reasons the United States used for locking them up.”

Also included in the releases by the Pentagon were the first ever lists of the prisoners that had been made public, and, although all the files released required significant cross-referencing to create a coherent account of all the prisoners held at Guantánamo, past and present, I was able, over a period of 14 months, to do just that, producing the first — and still the only — comprehensive account of all the prisoners who, in such a cavalier and unsubstantiated manner, had been described by the Bush administration as “the worst of the worst.”

The overwhelming majority of the men held — I would say as many as 97 percent of the 779 men held throughout Guantánamo’s history (of whom 116 remain) — had no involvement with terrorism, and were either humble foot soldiers for the Taliban or civilians unlucky enough to be in the wrong time and the wrong place while the US was handing out substantial bounty payments to its Afghan and Pakistani allies for anyone who could be packaged up as being involved with al-Qaeda and/or the Taliban.

Two of the men whose stories I pieced together at this time were Syrians – Abdul Nasir al-Tumani, in his early 40s, and his son Mohammed, 19 years old at the time of his capture according to the US authorities, but just 17 according to his own account – who, like roughly a third of the men and boys held at Guantánamo, were captured after crossing the Afghan border into Pakistan. These prisoners were all routinely regarded as “unlawful enemy combatants,” but in fact, while that label, invented by the US, shamefully failed to distinguish between soldiers and terrorists, it also failed to recognise that all manner of civilians had been fleeing Afghanistan in addition to those who were allegedly combatants — economic migrants, those fleeing religious persecution, missionaries, those involved in providing humanitarian aid, and businessmen.

As I described the father and son’s story in The Guantánamo Files:

The father had travelled to Afghanistan in1999 in search of work, finding a job in a restaurant in Kabul and bringing ten members of his family over in June 2001, including Mohammed, his grandmother and an eight-month old baby. Another six family members — his uncle’s family — arrived a week before 9/11, but after hearing about the attack on America the family fled to Jalalabad, where they stayed for a month, and then made their way on foot to Pakistan. On the way, their guide advised al-Tumani to let the women and children travel by car, to make them less of a target for highway robbers, but when he and his son arrived in Pakistan the local villagers handed them over to the Pakistani army.

Both men had eventually been recommended for release, but it had taken time for the US to find third countries that were prepared to offer them new homes. In August 2009, the son, Mohammed, was given a new home in Portugal, and in July 2010 his father was also resettled — but, disgracefully, not in Portugal but 1,850 miles away, in Cape Verde, an island nation off the west coast of Africa that was formerly colonized by the Portuguese.

I later spoke to Mohammed by telephone, on a visit to the United States, at the studio of Peter B. Collins, along with Debra Sweet, the director of the World Can’t Wait, and I had often wondered what had happened to him, and how — if — he had managed to stay in touch with his father. So I was pleased when, early this year, their lawyer, Pardiss Kebriaei of the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, wrote a detailed story about them that was published in Harper’s Magazine. Initially behind a paywall, it is now publicly available, and I’m cross-posting it below for the benefit of anyone who missed it when it was first published. It is a heartbreaking tale of wrongful arrest (sadly typical of the”war on terror”), of torture, of mental breakdown, isolation (three years of solitary confinement for Muhammed), and, eventually, after a one-hour reunion of father and son, release — but with no apology and no compensation for innocent lives ruined.

It is a powerful story, reminding me of why I have been working to get Guantánamo closed for the last ten years, and I hope you have the time to read it, and to share it if you find it as compelling as I did. I also wonder if, unlike me, you will be able to remain dry-eyed throughout it. I hope not.

Please note that Pardiss uses their correct names, not those used by their captors: Abdul Nasser and Muhammed Khantumani.

Life After Guantánamo: A father and son’s story

By Pardiss Kebriaei, Harper’s Magazine, April 2015

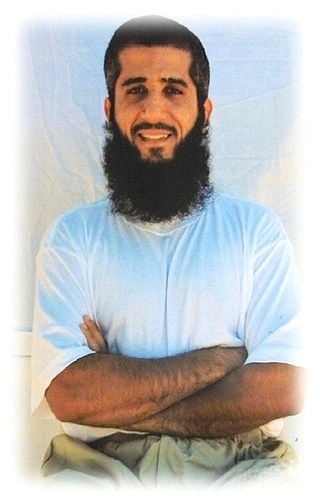

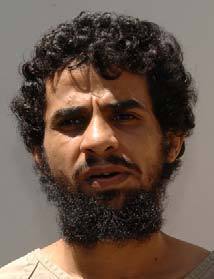

In 2008, I became the lawyer for Abdul Nasser Khantumani and his son Muhammed, two men who were being held at Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, in Cuba. When the United States took them into custody, in 2001, Abdul Nasser was in his forties; Muhammed was still a teenager, with a year of high school left. There’s a picture of him as a boy in Syria, not long before his life changed. He’s at the beach with his younger cousins, their arms draped over one another’s shoulders. He’s skinny and soaked, his wet hair plastered to his forehead.

On December 20, 2008, Muhammed cut one of his wrists in his cell. He smeared his blood on the walls, writing “COUNTRY OF INJUSTICE IS AMERICA.” Once his wounds had been treated, he wrote me a letter in which he listed the reasons for his act:

Being in this place, having been arrested when I was 17 years old

The continuous psychological pressure and the torture that I currently endure

The torture endured by prisoners in general

Being apart from my father

Current general torture

In another letter, he wrote diagonally, in all caps,

I SAY TO AMERICA DO WHATEVER YOU WANT THE PRISON HAD MADE MY HEART SUCH AS THE STONE FEEL WITH COMPLETE HOPELESSNESS I DON’T KNOW IF SOME PEOPLE KNOW THAT.

Muhammed had learned English in high school, and he had practiced it with the guards at Guantánamo and with his lawyers from the Center for Constitutional Rights, where I work. (I’ve corrected Muhammed’s misspellings and condensed some of his correspondence.) When I first met him, more than seven years after he was detained without charge, he had given up hope that he would ever be released. It took him a long time to change his mind.

The Khantumanis’ path to Guantánamo began in 2000, when Abdul Nasser left Syria after years of struggling to earn a living as a cook in his hometown of Aleppo. He ended up in Kabul, Afghanistan, where he didn’t need a visa to start a business, with the hope of opening a restaurant. In the summer of 2001, he called for his family to join him: his wife, his mother, his grandson, his brother, his in-laws, and his children — sixteen people in all.

Following the attack on the World Trade Center that September, word spread that the United States was planning to invade Afghanistan. Abdul Nasser gathered his family and drove east toward Pakistan, the closest border. When they stopped in Jalalabad, locals there told Abdul Nasser that it would be safer for the family to split into smaller groups before crossing the border. Everyone else made it out of Afghanistan and back home to Syria safely. Muhammed and Abdul Nasser, however, were arrested once they arrived in Pakistan.

They were not alone. In the aftermath of 9/11, the United States gave bundles of cash to Afghan warlords and to the Pakistani government for assistance in capturing suspected Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters. The Pakistani authorities turned over hundreds of men to U.S. custody, often with little or no evidence of wrongdoing.

The first round of questioning was conducted by the Pakistanis. The Americans joined them for later sessions, when the Pakistani interrogators broke Muhammed’s nose and tried to get him to say that he and his father were Al Qaeda. He points to his nose, which is still slightly crooked, every time we talk about what happened back then.

From Pakistan, Muhammed and Abdul Nasser were transferred back to Afghanistan — to Kandahar, where the United States had turned the city’s old airport into a temporary prison to dump and sort through its captives. The first night, guards knocked Abdul Nasser to the ground, put a boot on the back of his head, and bore down. They fractured his forehead. It’s still slightly indented.

Muhammed and Abdul Nasser were held in Kandahar for a month while American interrogators decided whether to ship them to Guantánamo. The criteria for detention at Guantánamo were broad. All captured Al Qaeda, Taliban, and foreign fighters, along with anyone “who may pose a threat to U.S. interests [or] may have intelligence value,” were marked for transfer. “I’m sure we’ll find that the first sort wasn’t perfect,” Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld remarked in an interview at the time.

The flight to Guantánamo was long, and Muhammed said it was hard to breathe through the hoods the prisoners were forced to wear. They were ordered not to speak, but the plane was still loud with voices. Men were shouting, “Oh God, oh God, oh God.” Muhammed would hear someone get kicked, then, “Oh God, oh God, oh God,” then another kick, over and over.

Muhammed and Abdul Nasser landed in Guantánamo in February 2002, just a month after the detention camp opened. Guards hustled the hooded prisoners onto a white school bus, which was ferried across the bay to the prison side of the U.S. naval base. More than 300 men were already being held there, outside, in six-by-eight-foot cells made of chain-link fencing.

When Muhammed’s hood came off that night, two months after his arrest in Pakistan, he was inside a cage, under floodlights, surrounded by the green hills of Cuba.

In late 2004, Muhammed and Abdul Nasser prepared long statements for their Combatant Status Review Tribunals, improvised military panels that had been created by President Bush to circumvent the Supreme Court’s decision, made earlier that year, to allow detainees to seek court review of their detention. At the time, father and son were in separate cells but within earshot of each other. Abdul Nasser had never gone to high school, so Muhammed helped him with his statement, at the risk of being punished for talking.

I have audio recordings of the hearings. Muhammed tittered nervously at odd moments during his testimony, as when he talked about getting his nose broken in Pakistan, or when he described being shocked with electric cables, threatened with rendition, and told that his family had been killed. Like other Guantánamo detainees, he hadn’t spoken to anyone but interrogators, guards, and a few other traumatized prisoners for years, so he felt strange in front of the panel, with press and other observers in the room.

On the recordings, Abdul Nasser’s voice sounds thin and emotional. He is five foot seven and 160 pounds, an inch taller and an inch wider than his son, with a gray beard and a receding hairline. When we first met, I tried not to show surprise when he told me his age. (He was forty-nine.) Muhammed said that even though he always felt fear in Guantánamo — of torture, of separation from his father — there was a different torment for men like Abdul Nasser who had left children and a wife behind. A few times during his hearing, Abdul Nasser’s alto voice went even higher than usual, as when he asked the members of the panel if they thought he would have brought his sixty-seven-year-old mother and eight-month-old grandson to Kabul if he’d known the September 11 attacks were coming.

I recently asked Muhammed about one of the tribunal members who sounded troubled by his testimony. “Yes, that person was sympathetic when I talked about my torture,” he said. “You could see it on their face. I felt like their hands were tied.”

The tribunal determined that Muhammed and Abdul Nasser were properly considered enemy combatants and ordered their continued detention. The government reached the same conclusion in almost all of the cases it reviewed.

Muhammed thinks that he started to crack sometime in 2005. That was the year he and his father were moved into separate camps. Interrogators learned early on that proximity to Abdul Nasser was a “comfort item” they could manipulate to try to make Muhammed talk. After Muhammed became uncooperative, they relocated him as a form of punishment. It would be years before they would hear each other’s voices again.

Muhammed started smearing excrement on his cell walls. He kicked a guard, and bit another. In late 2006, his “noncompliant” behavior got him sent to the base’s newly constructed supermax prison — Camp 6 — where he would later cut his wrists. In Camp 6, Muhammed was held in a windowless concrete-and-steel cell for at least twenty-two hours a day. He stayed in solitary confinement almost continuously for the next three years.

After Muhammed cut his wrists, I spoke with him on the phone. “Please do something,” he screamed. “I can’t be patient anymore.” I filed an emergency request asking for him to be moved from solitary confinement to his father’s camp. It was denied. Prison officials said that Muhammed had narcissistic traits and had cut himself to get attention. A few years earlier, an official at the State Department had called three alleged suicides at Guantánamo “a good PR move.”

In January 2009, after the Obama Administration took office and ordered Guantánamo’s closure, the government formed a task force to reevaluate the status of each detainee. Of the 779 men who had been held at the prison, the Bush Administration had already released more than 500. When President Obama took over, 242 detainees remained. The task force completed its work within the year, unanimously concluding that the continued detention of 126 men — more than half of the population — was not necessary for national security. In May, Muhammed and Abdul Nasser were told they were approved for transfer.

The Khantumanis could not return to Syria; they feared that the Assad regime would assume they were terrorists and torture them. Muhammed wrote a letter for me to give to the foreign ministries of several countries, asking for asylum:

Me and my dad are looking for a country to live in with no risks or hazards. Please if you like to offer some help don’t wait because seriously I can’t endure any more. I’ve seen the hell and I’m still in the beginning of my life.

A delegation from the Portuguese government came to Guantánamo to meet the men who had been approved for transfer. To help Muhammed and Abdul Nasser prepare for their interviews, I was allowed an hour-long phone call with each of them. “Put yourself in their shoes,” I told Muhammed. “They’ve never met anyone at Guantánamo. They’ve only heard what the United States has said about everyone here for years. Tell them you were a high school student when you were detained, that you’ve been through things most people can’t imagine. That you’re working on your English and your vocabulary is getting better than mine. That we talk about your dad’s cooking and your love for fried potatoes, which is so great that you once told your mother you love fried potatoes more than her. That you haven’t heard your mom say your name in seven years.”

Muhammed had just ended a two-week hunger strike, and he said he’d been given a pill that made him vomit up blood. He couldn’t sleep because of constant noise from the guards on his cellblock. “He’s in terrible condition,” I wrote in my notes. We spent at least half the time talking about his hunger strike and his vomiting.

My prep with Abdul Nasser went better. “God willing, wherever they put me, I want to live a quiet life with my family,” he said. For months, I’d been trying to send him orthopedic shoes for his foot pain, but the camp authorities wouldn’t deliver the package. “Don’t forget to bring me my shoes in Portugal,” he teased before we got off the phone.

The next conversation I had with Muhammed was more difficult. “I have good news and hard news,” I told him. “The good news is, Portugal is offering you resettlement. The hard news is that they are offering only you resettlement right now, along with another Syrian man. They are undecided about your father.” Muhammed was silent for a long time.

A few days later, he wrote a letter to his father that explained Portugal’s decision and made clear his distress about what he should do. When I gave the letter to Abdul Nasser, he didn’t hesitate. “Tell him he can go,” he said. “Go, and don’t be sorry.”

I asked the prison authorities to allow Muhammed to see Abdul Nasser so that he could hear his father’s blessing for himself. We got them an hour together, with one embrace at the beginning, one at the end, and no touching in between. I would not be alone with them in the room; a few guards would be joining us.

The afternoon of the meeting, Muhammed was already waiting when I walked in. He was sitting on the edge of his seat, across from an empty chair. I’d brought food from a Syrian bakery in Brooklyn — stuffed grape leaves, kibbe, and baklava — plus the usual staples from the base: pizza from Pizza Hut, salad from McDonald’s, fruit from the Navy Exchange. I spread it all out on paper plates as if we were getting ready for a party. Muhammed would be seeing his father for the first time in four years.

We heard the clinking of shackles outside the door. It opened a moment later and there was Abdul Nasser, in his baggy white-is-for-compliant T-shirt, elastic-waist pants, and flip-flops, a head shorter than the guards gripping his elbows on either side. He let out a choked laugh when he saw Muhammed, his eyes crinkling and filling with tears. The guards shuffled him over for the first embrace. He reached for his son and buried his face in Muhammed’s shoulder. They stood clasping each other, laughing, softly greeting each other in Arabic, while the rest of us looked down, or away.

Muhammed and Abdul Nasser sat down, faces shining, ankles shackled. An hour to reunite, say goodbye, seek forgiveness, give strength, imagine the future. They started with food. A salad, some fruit. At one point the rules slipped away, and Muhammed passed a plate of blackberries to his father, then to one of the guards. Not bad, the guard said, leaning forward to take another.

The meeting ended with the second embrace. “This isn’t goodbye,” Abdul Nasser said.

Muhammed had a list of twenty questions about what awaited him in Portugal, including “Are we going to get a home,” “In which city are we going to live,” “Are we going to be able to bring our family,” and “Is there potatoes enough or not.” He also wanted to ensure that he wouldn’t be sent back to Syria or to the United States or to “any other country that we may face risks or torture there.”

The U.S. government wouldn’t give me details about what Muhammed could expect in Portugal, so I gave him a picture book — Living in Portugal — and an Arabic-Portuguese dictionary. Muhammed told me he tried to memorize some Portuguese words in the days before his release, when he was still in solitary confinement, but he couldn’t do it.

Abdul Nasser asked me to give Muhammed a parting message. “Tell him to pursue his studies — computers or English,” he said. Muhammed asked me to tell Abdul Nasser to take care of his health, and that we would send news once he got to Portugal. “Tell him things are going to get better soon,” he said.

It was late one night in August 2009 when guards came to Muhammed’s cell and told him it was time to go. He was hooded and shackled — the same way he was hauled in seven years earlier — for the ride to the air terminal. We’d bought civilian clothes for his arrival in Lisbon: a button-down shirt, pants with a zipper, shoes with laces — all novelties.

When the plane reached Lisbon, Muhammed and Moammar Badawi Dokhan, the Syrian man released with him, were taken to a government villa on the outskirts of Lisbon. They were luckier in the resettlement lottery than the men released to Slovakia a few months later, whose reintegration to civilian life began in a quasi-detention facility.

A group of caretakers from the Portuguese government lived with the men 24/7, but that was fine with Muhammed. The government provided everything he needed, even if it controlled everything he did. He didn’t want to be alone anyway. The caretakers were warm to him, and he grew to like them. “They’re like Arabs,” he said.

Muhammed gave me dozens of pictures from his first few weeks to take back to Abdul Nasser. Muhammed squatting by a plant outside the villa. Muhammed standing in the kitchen next to a counter stacked with food. Muhammed in sunglasses, posing on a beachfront next to a tour bus. Muhammed after a swim, pale, sprawled on a lawn chair, eyes closed, face tilted up to the sun.

Articles in Portuguese and international newspapers that announced his arrival momentarily broke his reverie. They mentioned his suicide attempt, called him unstable, and labeled him a terrorist. The Portuguese caretakers joked with him and the other man, trying to put them at ease. One of the articles said that Dokhan once shook bin Laden’s hand. “Which hand? Can we take a picture?” they asked. Muhammed wasn’t consoled. He wrote a letter and asked me to give it to the Portuguese government.

Dear gentle. I don’t know how to thank you regarding whatever you had done to us. Let me introduce myself to you. I am Muhammed and my father is Abdul Nasser. I was born in 1983.

Sir what has been done by the news journalists is all untrue. I like to assure you that me or my father or the guy who lives with me now are not terrorists or have anything to do with them. America itself said that and cleared us from any terrorism problem and you know that already.

When I met with the Portuguese delegation I told them look I know America had told a lot of surreal information, so please feel free and ask me anything that you like to know, nothing will be hidden from you. I spoke with them about many things and I specialized which information was real or not.

So sir be sure that we are innocent and the days will prove that to you. The media as you know needs to work to get money. So even if we say not true, not true, every day we are going to hear new and new things from them. But I prefer to close my ear to it, especially for someone like me who was in G.T.M.O. under the legal age.

In late November, Muhammed graduated from the villa to an apartment in Lisbon. The Portuguese government rented another apartment across the hall, for his caretakers. He had a stipend but no plan for self-sufficiency, and his immigration status was still unresolved. He began learning Portuguese, got his eyes and teeth checked. He was allowed unlimited free calls to his government team thanks to a “friends and family” calling plan, but had no way to be with his real family.

Once, when he went to buy dinner plates at a housewares store, the shopkeeper thought he looked suspicious and called the police. An officer interrogated him on the street. Where is your I.D.? Where do you live? Muhammed walked him back to his apartment and called the caretakers to explain to the nice officer why he had no legal I.D. “Don’t leave the apartment by yourself again,” the team told him, “at least for now.”

It took Muhammed weeks to locate his family in Syria. All of his eight-year-old phone numbers had new owners. Finally, through a former neighbor, he made contact. More than a dozen relatives got on the landline in his sister’s house, one after another.

He gave me a long list of messages to take back to Abdul Nasser: Your nephew who was fourteen when you saw him is studying to be a lawyer. Your daughter had a baby girl who is four years old now. Your wife cried for a few minutes when she got on the phone. She is still patient and waiting for you. I told her that I was living in a house, cooking, and washing dishes, and she didn’t believe me. She said I never washed dishes when I was in Syria. I told her that I would try to find you a wife when you are released. She said she would cut me to pieces if I tried.

Muhammed spent a lot of time cooking for no one in particular, with his laptop open on the kitchen counter so that he could chat on Skype while he worked. His main Skype buddy was a former detainee named Mahrar Rafat al Quwari, a Palestinian who had been resettled in Hungary just after Muhammed arrived in Portugal. Al Quwari had been cleared to leave Guantánamo even earlier than Muhammed — in 2007, under the Bush Administration — but because he was stateless, he had stayed in prison during the three years it took the U.S. government to find a country that would take him. Half the time he and Muhammed didn’t even talk. They just went about their business while Skype was open so they could hear the sound of someone else in the room. Once when I visited, we all had dinner together — Muhammed and I at the table, al Quwari on the laptop. We held Muhammed’s dishes up to the screen to show al Quwari what he was missing.

Muhammed tried to stay busy in other ways. He and Dokhan took Portuguese lessons together. He went on a mission to find the most cost-efficient calling card to Syria. He made daily trips to the housewares store, buying a few items at a time to increase the number of outings. He played soccer with an amateur league, though he dropped out after a while: he didn’t want to tell his teammates about his past. He let his aunt try to set him up with a girl back home, but that went nowhere; there was no chance that the Syrian government was going to let her travel to Portugal — it had already rejected his family’s request to visit him. All the while, he held on to the hope that his father would soon be with him, even if his mother couldn’t be. He took pictures of himself dining alone that he asked me to give to Abdul Nasser. “Let’s see who is the better cook when you are here,” he said in a message to his father.

By early 2010, after it became clear that Portugal was not going to allow Abdul Nasser to join his son, Muhammed wrote a letter to the Portuguese authorities:

Greetings to whom it may concern

The purpose of this letter is not to blame you for what happened to me, and I am neither seeking to share with you that feeling of sadness that has been haunting me.

When you sent your delegation to meet with me in Guantánamo, even though I was still imprisoned and was suffering from torture, it made me feel as if I was already released from prison, because I met with human beings who have that sense of humanity. I also felt that the brutality which had been inflicted on me for the last 8 years was just about to end; and indeed, it ended. I felt optimistic when I was told, “Come now and if the program goes well there will be a great chance for your father to join you.”

I was truly very enthusiastic about building my future despite the trauma I suffered from being separated from my father. What made me even more enthusiastic was the amount of assistance I received from the Portuguese government. In fact no one can deny nor ignore what you have done for me.

Yet now that I have crossed half the road I feel day after day that things are going backwards. I am physically free, yet I feel like I am mentally imprisoned. This is the worst kind of detention.

You too are all fathers and mothers and you can feel what I feel. You may choose to live away from them, but I am sure you can visit them and they can visit you as well. In my case I can’t visit them and they can’t visit me, and you all know that.

It is very easy for the U.S. government to use a political argument to separate me from my father. It’s easy for a country to do such a thing when it claims to be the beacon of humanity, to be against torture and against human rights violations, yet it does it solely through slogans and words. However, what is really stunning is when an E.U. country like Portugal condones America’s actions when we all know that Portugal is considered the second country in the world following Sweden when it has to do with protecting families. I’m not trying here to dictate to Portugal what it should do in this case, yet I feel I should tell Portugal that it shouldn’t have taken me without my father, because it was for humanitarian reasons that they decided to take me.

I sincerely say that what the Portuguese government has done for me was magnificent. However, I will not live here without my father and he cannot lead his life without me either. No one should ask why someone would make such a request. Nevertheless, I will mention some of these reasons:

This is my basic right and it is based on Portuguese laws that stipulate that after spending one full year in Portugal a refugee is entitled to bring a family member to the country.

My father is an older man and needs to be taken care of, and no one but me could offer him the care he needs. One might say that he is not that old and my response would be, “Don’t forget that he has been in jail and tortured for close to nine years.”

My father has little reading and writing capabilities and that will make it hard for him to live alone.

My father does not speak a foreign language which is an important thing. Look how difficult it was for you to find me a language instructor who is fluent in both Arabic and Portuguese. I am willing to take care of teaching my father Portuguese.

We cannot reunite with any of our relatives. I am all he’s got and he’s all I got.

We don’t have any relative who lives in a foreign country and who could go and live with him.

It is not going to be easy for him to find a job because of his age and the time he spent in prison.I will not accept to live without my father, and no decent person would accept to turn it into a political matter. If the reason is financial I am willing to give up everything and in return be reunited with my father. If the problem is the purchase of the airline ticket, Albania, Palau, and Bermuda are much poorer than Portugal and still took close to 10 men.

Finally, I don’t want to leave Portugal if you bring me back my father who is all my life, yet I don’t want to stay here if my father can’t come to live with me. When they took my father away from me in prison I felt like I don’t have anything left in life, and when he was brought back to me I felt like I became life itself. I will never give up my father, and if I’ll ever have to do it that will mean that I am ready to give up my life.

I apologize for taking too much of your time but I am asking you to put yourselves in my shoes.

Thank you very much.

In 2010, Cape Verde, a former Portuguese colony off the coast of Senegal, agreed to take Abdul Nasser. I showed him where it was on a map, drawing a line from Cuba to a small archipelago in the Atlantic. “It’s another island?” he asked.

Muhammed thought it sounded like a terrible idea. He wrote out a numbered list and told me to give it to his father:

It is going to be so hard for you to speak the language

You are going to be transferred alone

You are going to a country that you didn’t ever know or entered it before

There is no one from your family can join you because they are not allowed to travel

It may be like another Guantánamo but with small shape

There is no guarantees from any side — American or Portuguese — that they are going to gather us in the futureSo please think completely and don’t do anything before consultation.

Abdul Nasser wanted assurances that he would be able to reunite with his family. But he had also spent nearly a year in Guantánamo since Muhammed had been released. And the threat of congressional restrictions on transfers was looming. By the time Cape Verde made a concrete offer, Abdul Nasser had made up his mind. “The matter is out of our hands,” he said. “I’ve had enough. Let me get out of this hole.”

Abdul Nasser was transferred to Cape Verde on July 19, 2010. A few months later, Congress passed its restrictions. The Obama Administration abandoned its efforts to close the prison for the next three years. Dozens of men cleared for release were trapped in Guantánamo.

In the days leading up to Abdul Nasser’s transfer, Muhammed had shared more wisdom with his father.

Try to speak with the military before you leave the block. Tell them, I don’t want you to hood me or cover my ears. Be patient, they may search your genitals.

In the airplane try to ask for restroom, they will allow it. They won’t leave the door open.

Try to ask for a walk inside the plane every hour. Tell them, I need to walk. They will allow it.

When you get there, there will be a car waiting with a few people. When you get in the car, ask for a call with me directly.

Don’t be shocked when you get there. Remember to shake people’s hands. The man with me forgot to say hello and shake hands.

The first week, you will be amazed at the little things. Don’t be surprised if you sleep and you cover your head, and you think, am I allowed to cover my head? It is crazy when you remember where you were and where you are.

All of the family sends you their best, best, best congratulations. They are just waiting to hear your voice.

I visited Abdul Nasser a few weeks after he arrived in Cape Verde. An official from the government picked me up from the airport in Praia and drove toward the mountains on the outskirts of the city. Eventually we arrived at the only house on a rocky strip of beach. We were 1,850 miles from Portugal.

I had brought Abdul Nasser his orthopedic shoes. He laughed and held back tears when he saw me take them out of my bag. I stood in the kitchen while he cooked a lunchtime feast for us of fish and fried potatoes, in honor of Muhammed.

A few weeks later, when I was back in New York, I set up a conference call with Muhammed, Abdul Nasser, and their family in Syria.

“Who’s the next person?” I asked Muhammed.

“My aunt,” he called out over seven excited voices having three separate conversations in Arabic. “I gave you the number.”

We had ten people on the call, one from Lisbon, another from Cape Verde, seven from Aleppo, and me. The family’s first reunion after nearly a decade apart. They were laughing, whooping, crying, talking over one another. I stood for a moment listening to the party before I left the room to let them have their privacy.

The family conference calls continued for nearly another year. Portugal and Cape Verde, perhaps under pressure from the United States, wouldn’t permit Muhammed and Abdul Nasser to visit each other. Syria still wouldn’t permit the rest of the family to leave the country.

Abdul Nasser probably needed the calls the most, since he couldn’t communicate with anyone around him. He didn’t have his son’s knack for languages, and the island didn’t have the infrastructure to help him learn. He depended entirely on an interpreter — an Arabic speaker the government found abroad and flew to Cape Verde — to be his voice at the market, at the doctor’s office, at meetings with his government contacts.

In March 2013, Muhammed got permission to fly to Turkey to see his family. They had fled the civil war in Syria four months earlier and were living in a refugee camp near Gaziantep. By then Muhammed and Abdul Nasser had lost nearly a dozen relatives in the violence.

Traveling with Muhammed to meet his family for the first time was his wife. She and Muhammed had met two years earlier and had just gotten married. When he saw his family at the hotel in Gaziantep, he had to stop himself from sprinting across the lobby. There was his eight-month-old nephew, now twelve, and his niece, now seven years old, who almost knocked him down when she hugged him. Standing behind them was his mother, who held him for a very long time.

Muhammed told me that their faces were dusty from the refugee camp. It was shocking to see them, he said. They had all aged so much.

Abdul Nasser wasn’t allowed to leave his island for the reunion. Muhammed took many pictures of their tear-streaked faces to hold up for Abdul Nasser over Skype. He has gotten used to documenting his life in photographs for his father.

Two years later, Abdul Nasser remains alone in Cape Verde. The rest of the family is still in Gaziantep. But not too long ago, I got an email from Muhammed.

Well, I am a little bit angry at you because I emailed you last week to share in my happiness, but you didn’t see it or receive it. But I like to tell you that you have been an aunt since the Valentine day.

My dear daughter was born on 14th of February and here she is.

He attached a picture. Muhammed’s daughter is a fuzzy bundle nestled in the crook of his arm. He’s holding her up, looking into the camera, touching his cheek to her forehead.

It had been nearly five years since his release. He didn’t look like a former prisoner. He looked like a new dad.

Note: The photo at the top of this article is a screenshot from an interview with Pardiss Kebriaei on Democracy Now, available here. Please also see Pardiss’s video in which she mentioned the Khantumanis after Sen. Tom Cotton visited Guantánamo and made inflammatory comments about the prisoners earlier this year.

September 4, 2015

Huge Victory for Prison Reform as California Ends Indeterminate Long-Term Solitary Confinement

On Tuesday, a significant victory took place in the long struggle by campaigners — and prisoners themselves — to improve detention conditions in US prisons, when a settlement was reached in Ashker v. Governor of California, a federal class action lawsuit on behalf of prisoners held in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison who have spent a decade or more in solitary confinement.

On Tuesday, a significant victory took place in the long struggle by campaigners — and prisoners themselves — to improve detention conditions in US prisons, when a settlement was reached in Ashker v. Governor of California, a federal class action lawsuit on behalf of prisoners held in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison who have spent a decade or more in solitary confinement.

In a press release, the Center for Constitutional Rights, whose lawyers represented the prisoners, with co-counsel from other lawyers’ firms and the organizations California Prison Focus and Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, stated that the “landmark” settlement “will effectively end indeterminate, long-term solitary confinement in all California state prisons,” resulting in “a dramatic reduction in the number of people in solitary across the state and a new program that could be a model for other states going forward.”

As CCR noted, the class action “was brought in 2012 on behalf of prisoners held in solitary confinement at the Pelican Bay prison, often without any violent conduct or serious rule infractions, often for more than a decade, and all without any meaningful process for transfer out of isolation and back to the general prison population.” The case argued that California’s use of prolonged solitary confinement “constitutes cruel and unusual punishment and denies prisoners the right to due process.”

All this was inarguable, and yet it has taken decades to reach this momentous point. Back in July 2011, I picked up on the Pelican Bay story when, first of all, I received a press release from the Prison Hunger Strike Solidarity Coalition in Oakland, California, as prisoners held in Pelican Bay and five other Californian prisons embarked on a hunger strike, and, secondly, when I received a message from my friend Debra Sweet of the World Can’t Wait, who asked me “if I saw similarities between America’s domestic prisons and the hunger strikers of Pelican Bay and the prisoners at Guantánamo.” Debra stated that the Pelican Bay hunger strike came about “in response to conditions in the Security Housing Units (SHU) of extreme isolation, brutality, deprivation — conditions so severe they violate the US Constitution and international laws on torture. Very significantly, the strike has brought together Black and Latino prisoners who are normally set against each other. They are asserting their own humanity and challenging others to reclaim their humanity by standing with them.”

Hunger strikers at one of the prisons, Corcoran State Prison, released a statement that said, “Our indefinite isolation here is both inhumane and illegal and the proponents of the prison industrial complex are hoping that their campaign to dehumanize us has succeeded to the degree that you don’t care and will allow the torture to continue in your name. It is our belief that they have woefully underestimated the decency, principles and humanity of the people. Join us in opposing this injustice without end. Thank you for your time and support.”

The prisoners had five demands, one of which involved a call for an end to solitary confinement for those perceived to be gang members. These perceptions are often wrong — CCR noted that they were often based on evidence “as innocuous as having supposedly gang-related artwork or tattoos” — and yet those regarded as gang members could then be put into solitary for years — or decades — with no way out. The prisoners also complained about “debriefing,” or “offering up information about fellow prisoners particularly regarding gang status,” which was “often demanded in return for better food or release from the SHU.”

In an article for FireDogLake, Kevin Gosztola explained how solitary confinement had become popular in the 1980s, as a way of isolating potentially troublesome prisoners, who were “confined to their cells without yard time, work or any kind of rehabilitative programming.” He added that, “in 1989 California built the first supermax — Pelican Bay. There was a supermax boom in the 1990s, and today, 40 states and the federal government have supermax prisons holding upwards of 25,000 inmates. Tens of thousands more are held in solitary confinement in lockdown units within other prisons and jails. There’s no up-to-date nationwide count, but according to best estimates, there are at least 75,000 and perhaps more than 100,000 prisoners in solitary confinement on any given day in America.”

As the author and university professor Colin Daylon wrote for the New York Times, “Many of these prisoners [in solitary confinement] have been sent to virtually total isolation and enforced idleness for no crime, not even for alleged infractions of prison regulations. Their isolation, which can last for decades, is often not explicitly disciplinary, and therefore not subject to court oversight. Their treatment is simply a matter of administrative convenience. Solitary confinement has been transmuted from an occasional tool of discipline into a widespread form of preventive detention.”

I continued to report on the hunger strikes and the demands for an end to indiscriminate solitary confinement in July 2011, cross-posting the devastatingly powerful New Yorker article ‘Hellhole’, about long-term solitary confinement and why it is torture, and following the hunger strikers into the fall, and into 2012, when, “Comparing their conditions to a ‘living coffin,’ 400 California prisoners held in long-term or indefinite solitary confinement petitioned the United Nations … to intervene on behalf of all of the more than 4,000 prisoners similarly situated,” as a local paper put it.

Shortly after that, Ashker v. California was filed, amending an earlier pro se lawsuit that was filed, in 2009, by two Pelican Bay SHU prisoners, Todd Ashker and Danny Troxell.

And while the lawyers must be thanked for all their hard work, two of CCR’s attorneys on the case, Alexis Agathocleous and Rachel Meeropol, made clear that none of this would have been possible without the prisoners themselves. In an article on CCR’s website, they wrote:

The struggle to end California’s extreme use of solitary confinement has always been led by people in prison and their families, organizing through the prison walls. Incarcerated activists first brought the case that became Ashker and organized the hunger strikes that made the barbaric reality of solitary a political and policy issue. Throughout the lawsuit, our plaintiffs were involved at every step, and the settlement gives them an unprecedented role in monitoring compliance with its terms. Their organizing efforts – in the face of unimaginable obstacles – have been extraordinary.

They also made available an extraordinary video featuring the Ashker plaintiffs, held between 14 and 25 years in solitary confinement — Todd Ashker, Sitawa Nantambu Janaa, Paul Redd, Jeffrey Franklin, George Franco and Gabriel Reyes.

That video is posted below via YouTube:

Nine of the prisoners — Todd Ashker, Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa, Luis Esquivel, George Franco. Richard Johnson, Paul Redd, Gabriel Reyes, George Ruiz and Danny Troxell — also issued the following statement:

This settlement represents a monumental victory for prisoners and an important step toward our goal of ending solitary confinement in California, and across the country. California’s agreement to abandon indeterminate SHU confinement based on gang affiliation demonstrates the power of unity and collective action. This victory was achieved by the efforts of people in prison, their families and loved ones, lawyers, and outside supporters.

Our movement rests on a foundation of unity: our Agreement to End Hostilities. It is our hope that this groundbreaking agreement to end the violence between the various ethnic groups in California prisons will inspire not only state prisoners, but also jail detainees, county prisoners and our communities on the street, to oppose ethnic and racial violence. From this foundation, the prisoners’ human rights movement is awakening the conscience of the nation to recognize that we are fellow human beings.

As the recent statements of President Obama and of Justice Kennedy illustrate, the nation is turning against solitary confinement. We celebrate this victory while, at the same time, we recognize that achieving our goal of fundamentally transforming the criminal justice system and stopping the practice of warehousing people in prison will be a protracted struggle. We are fully committed to that effort, and invite you to join us.

Lead attorney Jules Lobel, the President of the Center for Constitutional Rights, also issued a statement, calling the settlement “the result of the extraordinary organizing the prisoners managed to accomplish despite extreme conditions,” and adding, “This far-reaching settlement represents a major change in California’s cruel and unconstitutional solitary confinement system. There is a mounting awareness across the nation of the devastating consequences of solitary — some key reforms California agreed to will hopefully be a model for other states.”

Carol Strickman, staff attorney at Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, also said, after the settlement was announced, “The seeds of this victory are in the unity of the prisoners in their peaceful hunger strike of 2011. That courageous and principled protest galvanized support on both sides of the prison walls for a legal challenge to California’s use of solitary confinement.”

As CCR noted, when Ashker was first filed in 2012, “more than 500 prisoners had been isolated in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at Pelican Bay for over 10 years, and 78 had been there for more than 20 years. They spent 22½ to 24 hours every day in a cramped, concrete, windowless cell, and were denied telephone calls, physical contact with visitors, and vocational, recreational, and educational programming.” Hundreds of other prisoners throughout California, CCR also noted, “have been held in similar SHU conditions.”

CCR added that the settlement “transforms California’s use of solitary confinement from a status-based system to a behavior-based system; prisoners will no longer be sent to solitary based solely on gang affiliation, but rather based on infraction of specific serious rules violations. It also limits the amount of time a prisoner can spend in the Pelican Bay SHU and provides a two-year step-down program for transfer from SHU to general population.”

The agreement also “creates a new non-solitary but high-security unit for the minority of prisoners who have been held in any SHU for more than 10 years and who have a recent serious rule violation. They will be able to interact with other prisoners, have small-group recreation and educational and vocational programming, and contact visits.”

Extensive expert evidence submitted in the case had established “severe physical and psychological harm among California SHU prisoners as a result of prolonged solitary confinement.” The plaintiffs “worked with 10 experts in the fields of psychology, neuroscience, medicine, prison security and classification, and international human rights law,” and the reports provided “an unprecedented and holistic analysis of the impact of prolonged solitary confinement on human beings,” as well as “guidance in the construction of the settlement reforms.”

As CCR also noted, the key reforms include the following:

Prisoners will no longer be sent to solitary based solely on gang affiliation, but rather based on specific serious rules violations. The Ashker settlement ends California’s status-based practice of solitary confinement, transforming it into a behavior-based system.

Under the system challenged in the lawsuit, Prisoners validated as gang affiliates used to face indefinite SHU confinement, with a review for possible release to general population only once every six years, at which even a single piece of evidence of alleged continued gang affiliation led to another six years of solitary confinement. That evidence was often as problematic as the original evidence used to send them to SHU – for example, a book, a poem, or a tattoo that was deemed to be gang-related.

Under the settlement, California will generally no longer impose indeterminate SHU sentences. Instead, after serving a determinate sentence for a SHU offense, prisoners whose offense is related to gang activity will enter a two-year, four-step, step-down program to return to the general prisoner population. Prisoners will receive increased privileges at each step of the step-down program.

California will review all current gang-validated SHU prisoners within one year of the settlement to determine whether they should be released from solitary under the settlement terms. The vast majority of such prisoners are expected to be released.

Virtually no prisoner will ever be held in the SHU for more than 10 continuous years.

California will create a modified general-population unit for a very small number of prisoners who repeatedly violate prison rules or have been in solitary over 10 years but have recently committed a serious offense. As a high-security but non-isolation environment, this new unit allows prison administrators to begin to balance the humanity of the prisoners with the security of the prison, creating a realistic alternative to long-term solitary for the minority of “hard cases.” Prisoners held in this unit will be allowed to move around the unit without restraints, will be afforded as much out-of-cell time as other general population prisoners, and can receive contact visits.

Prisoners themselves will have a role in monitoring compliance with the settlement agreement. Prisoner representatives will meet regularly with California prison officials to review the progress of the settlement, discuss programming and step-down program improvements, and monitor prison conditions.

Responding to the settlement, the New York Times noted how “Craig Haney, a psychologist who studied the effects of isolation on prisoners at Pelican Bay State Prison in Northern California — the prisoners at the heart of this settlement — used the term ‘social death’ to describe the impact on their psyche.” The Times added that “[a] number of corrections officials across the country are also coming to see locking up inmates for years at a time as ineffective.”

Providing figures for the reforms, the Times also noted that, at the time of the settlement, “2,858 prisoners were in solitary housing units across the state,” but “that figure could fall by as many as 1,800 inmates, bringing it ‘more in line with other states,'” as Jeffrey Beard, the secretary of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said at a news conference, although more than 1,100 prisoners remain in solitary confinement in the windowless cells of Pelican Bay

Beard called the settlement “part of an effort the state had already been making to reduce the number of prisoners in solitary confinement.” As the Times described it, he said that “[m]ore than 1,000 inmates who had been held in isolation units because of gang affiliations have already been released over the last several years, and few have caused problems in the general population.”

He claimed that, in the 1970s and 1980s, “there was a lot of violence in the system,” and “you had to do something to stop the violence,” although he added that “the problem was you had a system that was so overcrowded over the years that they just went from one crisis to anther.”

Explaining the current changes, he said, “We moved slow at first, because this represented a big change. Any time when you try to change something that you’ve been doing for over 30 years, there is the risk of having problems.” However, he added that the department now had “the tools to deal with those people when they emerge” from the solitary units, and he also said, “We don’t believe it’s good for anybody to keep them locked up for 10, 20, 30 years” in isolation, a concession that is welcome, if long overdue.

As the Times noted, “Solitary confinement has come under increasing scrutiny across the country, as research has revealed the effects of long-term isolation on the psyche. The suicide of Kalief Browder in June, after nearly two years in isolation at Rikers Island in New York City, brought renewed attention to young people in solitary confinement. That same month, Justice Anthony Kennedy of the Supreme Court seemed to invite a constitutional challenge to prolonged solitary confinement.”

In an editorial in June, the Times‘ editors noted Justice Kennedy’s comments in the case of Hector Ayala, who has been on California’s death row for 25 years:

It is likely, Mr. Kennedy wrote, that Mr. Ayala “has been held for all or most of the past 20 years or more in a windowless cell no larger than a typical parking spot for 23 hours a day; and in the one hour when he leaves it, he likely is allowed little or no opportunity for conversation or interaction with anyone.” The Supreme Court has rarely mentioned this practice, and it has never ruled on whether the practice violates the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishments. But as Justice Kennedy wrote, this sort of “near-total isolation exacts a terrible price,” long understood by courts and commentators.

In making his point, he quoted Dostoyevsky: “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” He cited the case of Kalief Browder … And he noted research showing that solitary confinement is most harmful to young people and the mentally ill, who often end up in prison.

This is not the first time Justice Kennedy has aired his concerns about solitary confinement — he spoke out against the practice during testimony before Congress in March. But in addressing the brutality of this punishment at length in an opinion, he raises a constitutional question even if some of his colleagues would rather avoid it.

The editorial concluded:

Justice Kennedy seemed eager to consider whether prolonged solitary confinement is unconstitutional. If faced with a lawsuit raising this issue, he wrote, the courts may have to decide “whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and, if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.” In other words, he was saying, bring us a case.

Perhaps one day, Justice Kennedy will have his wish granted — although it is by no means certain that a majority of the Justices would appreciate the raising of such a constitutional question. For now, however, it is worth celebrating the achievements of the prisoners in California, their lawyers — and, I hope, the prison authorities, who seem finally to be accepting that prolonged solitary confinement, which they have embraced more thoroughly than anywhere else in the US, is wrong and must be stopped.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 3, 2015

As the Death of Three-Year Old Syrian Refugee Aylan Kurdi Appals All Decent People, Please Sign the E-Petition Asking the UK Government to Accept More Refugees

Please sign and share this e-petition to the British government, calling for more asylum seekers to be accepted into the country, as the UK tries to turn its back on this huge humanitarian crisis.

Please sign and share this e-petition to the British government, calling for more asylum seekers to be accepted into the country, as the UK tries to turn its back on this huge humanitarian crisis.Amazingly, it has gone from 27,000 signatures last night to over 112,000 signatures this morning, making it eligible for a Parliamentary debate. Please keep signing and sharing it, however, so that the government knows the depth of feeling in this country. UPDATE 4pm: It has now reached 200,000 signatures.

*****

I’m not posting the photo above of the dead body of three-year old Syrian refugee Aylan Kurdi for sensationalist reasons, but simply because, when it went viral yesterday, it did so because millions of people identified with it, whether they were parents or not.

I am a parent. My son is 15 years old, but I remember vividly when he was three, and when I saw, yesterday, the photo of Aylan’s lifeless body washed up on Bodrum beach in Turkey, I felt his loss viscerally.

I was at that beach just two weeks ago, aware that refugees from Syria were trying to make their way to Europe via the Greek islands, and aware that some of them were dying in search of a new life.

I was already appalled by my government’s disdain for the huge number of refugees leaving Africa and the Middle East — many from countries we have helped to destabilise (Syria and Libya, for example). In May, for example, as the death toll in the Mediterranean reached 1,800 this year, Theresa May, the home secretary, was refusing calls for an EU quota for refugees, and disagreeing with a suggestion by the EU’s High Representative, Federica Mogherini, that “no migrants” intercepted at sea should be “sent back against their will.” The BBC reported that she said, “Such an approach would only act as an increased pull factor across the Mediterranean and encourage more people to put their lives at risk.”

She told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme that “many of the people coming across the central Mediterranean were not refugees, but economic migrants from places such as Nigeria, Eritrea and Somalia” — an appalling and unfair generalisation, when Eritrea currently has the worst human rights record in the world, and Somalia is a country ravaged by war.

Last week, after it was reported that more than 80 Syrian and Palestinian refugees, many of them young children, had drowned in the Mediterranean, a petition addressed to Theresa May, ‘No more drownings. Immediate sanctuary for those fleeing from war‘, was launched on Change.org, which currently has over 160,000 signatures (up from 135,000 last night).

Please sign and share this petition, and please also sign and share a new petition on Change. org, launched by the Independent, addressed to David Cameron. The petition, ‘Britain must accept its fair share of refugees seeking safety in Europe‘, currently has over 44,000 signatures (up from 13,000 last night), and states, “Millions of men, women and children are fleeing the Middle East and Africa to find safety in the West. The Independent believes Britain must no longer turn a blind eye to their plight and must work with other European Union countries to set and welcome a quota of refugees.”

The timing could not have been more apposite. As the photo of Aylan Kurdi went viral, David Cameron attempted to defend Britain’s inaction, in a display of heartlessness that was astonishing, under the circumstances.

“We have taken a number of genuine asylum seekers from Syrian refugee camps and we keep that under review,” Cameron said, “but we think the most important thing is to try to bring peace and stability to that part of the world. I don’t think there is an answer that can be achieved simply by taking more and more refugees.”

Given how Britain has been involved in Syria — first supporting the opposition to President Assad, and then turning on them — it is extraordinarily hypocritical of Cameron to try and wash his hands of the Syrian refugee crisis.

And, of course, anyone looking at who has done what would discover that, while Germany is pledging to take in 1% of its population — that’s 800,000 asylum seekers — the UK has taken in just 216 Syrian refugees.

As the Washington Post noted, “Of the 4 million Syrians who have fled their country since the war began, including hundreds of thousands who have poured into Europe, the number who have been resettled in Britain could fit on a single London Underground train — with plenty of seats to spare. Just 216 Syrian refugees have qualified for the government’s official relocation program, according to data released last week. (Tube trains seat about 300.) British Prime Minister David Cameron has reassured his anxious public that the total number won’t rise above 1,000.”

Please also, if you haven’t already, sign and share the e-petition I mentioned above, ‘ Accept more asylum seekers and increase support for refugee migrants in the UK ,’ which was launched on August 13. When I signed it last night, it had 27,000 signatures, within two hours it had reached 48,000 signatures, and this morning I awoke to find that it now has over 112,000 signatories.

Like all e-petitions, it needed 100,000 signatures within six months to be eligible for a Parliamentary debate, but, as I mentioned above, please keep signing and sharing it so the government knows that its callous disregard for the refugees fleeing Syria and elsewhere is not shared by the British people. The petition states, “There is a global refugee crisis. The UK is not offering proportional asylum in comparison with European counterparts. We can’t allow refugees who have risked their lives to escape horrendous conflict and violence to be left living in dire, unsafe and inhumane conditions in Europe. We must help.”

I hope you agree with the sentiments in these petitions, and that, like me, you want people’s humanity and empathy to triumph over the kind of mean, small-minded racism and xenophobia that has been thriving of late. No child should be dying like Aylan Kurdi, and if we all pull together and tell our governments that we will not be silent, and that we demand action, we may just be able to make the world a slightly better place, one in which small children are not dying because of our indifference to their suffering.

Note: If you want to do more, please visit this page on the Independent‘s website, “5 practical ways you can help refugees trying to find safety in Europe,” which includes links for making donations, and for getting involved with grass-roots groups visiting Calais to help those in the refugee camps there.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ was released in July 2015). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 2, 2015

Mohammed Kamin, an Insignificant Afghan Prisoner in Guantánamo, Asks Review Board to Recommend His Release

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

On August 18, Mohammed Kamin, an Afghan prisoner at Guantánamo who is 36 or 37 years old, became the 17th prisoner to have his case reviewed by a Periodic Review Board, consisting of representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.