Andy Worthington's Blog, page 83

December 15, 2015

For Christmas, Buy My Books on the UK Counter-Culture and Guantánamo and My Music with The Four Fathers

If anyone out there hasn’t yet completed their Christmas shopping and would like to buy any of my work, I’m delighted to let you know that all three of my books — about Guantánamo and the UK counter-culture — are still available, as is the album “Love and War,” recorded with my band The Four Fathers and released just a few months ago.

If anyone out there hasn’t yet completed their Christmas shopping and would like to buy any of my work, I’m delighted to let you know that all three of my books — about Guantánamo and the UK counter-culture — are still available, as is the album “Love and War,” recorded with my band The Four Fathers and released just a few months ago.

From me you can buy my first two books, Stonehenge: Celebration & Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield.

Stonehenge: Celebration & Subversion is a social history of Stonehenge, interweaving the stories of the outsiders drawn to Stonehenge, primarily over the last hundred years — Druids, other pagans, revellers, festival-goers, anarchists, new travellers and environmental activists — with the monument’s archeological history, and also featuring nearly 150 photos. If you’re buying this from me from anywhere other than the UK, please see this page. You can also buy it from Amazon in the US.

The Battle of the Beanfield focuses on the events of June 1, 1985, when a convoy of travellers driving to Stonehenge to establish what would have been the 12th annual free festival were ambushed, assaulted and arrested with unprecedented brutality by a quasi-military police force of over 1,300 officers drawn from six counties and the MoD, in what has become known as the Battle of the Beanfield. The book features extracts from the police radio log and in-depth interviews with a range of people who were there on the day, as well as over 100 photos. Again, if you’re buying this from me from anywhere other than the UK, please see this page.

I also have a few copies of my third book, The Guantánamo Files — the book that launched my current career as an expert on Guantánamo, and a campaigner for the closure of the prison — but only rather expensive hardback copies. I sold all my paperbacks, but a few copies are still available via Amazon — in the UK and in the US. Amazon also has the book on Kindle. If you want one of the few hardback copies left, and are ordering from outside the UK, please see this page.

You can also buy “Love and War,” the album I recorded with my band The Four Fathers, who play a mix of rock and roots reggae, and are not afraid of political engagement. The album is available on Bandcamp, where you can either buy it as an 8-track download, or buy individual tracks to download, or you can buy it as CD with two bonus tracks. The album primarily features original songs I have written, including “Song for Shaker Aamer,” which was used in the campaign video for the We Stand With Shaker campaign I established last November with an activist friend, Joanne MacInnes, “81 Million Dollars,” about the US torture program, and two denunciations of the cynical “age of austerity” imposed after the banker-led global economic crash of 2008, “Tory Bullshit Blues” and the roots rocking anthem “Fighting Injustice,” which is a live favourite. The bonus tracks on the CD are covers of Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War,” and a groovy, folky take on “I Will Survive.”

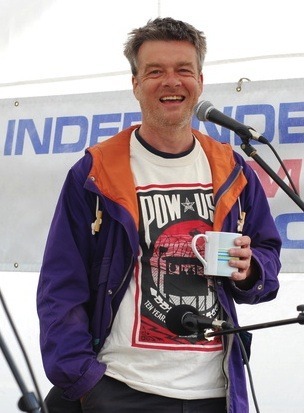

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

December 14, 2015

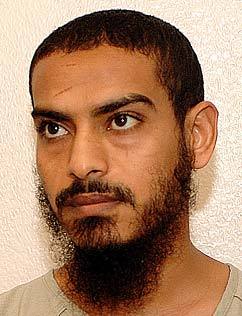

Shaker Aamer Discusses His 13 Years in Guantánamo, Built to “Destroy Human Beings,” and Adjusting to Freedom Since His Release

The Mail on Sunday yesterday featured the first interview conducted by Shaker Aamer since his release from Guantánamo six weeks ago, and below, following my first article yesterday, are excerpts dealing with his 13 years and eight months in Guantánamo — over 5,000 days — and his adjustment to life since his release: the changes in the world, and, in particular, getting to know his family again after so long separated from them. Also included are great anecdotes about Shaker helping someone in a wheelchair — a rather typical act, I believe, for someone renowned for wanting to help others — and what happened when he tried to open a bank account. As the co-founder of the We Stand With Shaker campaign, established just over a year ago to call for his release, it is reassuring to me that he has now undertaken major media interviews — including with ITV News and with The Victoria Derbyshire Show on BBC2, broadcast today — and that he will, hopefully, soon be free to devote more of his time to campaign for the closure of Guantánamo. If viewers outside the UK have difficulty accessing the broadcasts, there are clips from the BBC interview on Twitter here, here and here.

The Mail on Sunday yesterday featured the first interview conducted by Shaker Aamer since his release from Guantánamo six weeks ago, and below, following my first article yesterday, are excerpts dealing with his 13 years and eight months in Guantánamo — over 5,000 days — and his adjustment to life since his release: the changes in the world, and, in particular, getting to know his family again after so long separated from them. Also included are great anecdotes about Shaker helping someone in a wheelchair — a rather typical act, I believe, for someone renowned for wanting to help others — and what happened when he tried to open a bank account. As the co-founder of the We Stand With Shaker campaign, established just over a year ago to call for his release, it is reassuring to me that he has now undertaken major media interviews — including with ITV News and with The Victoria Derbyshire Show on BBC2, broadcast today — and that he will, hopefully, soon be free to devote more of his time to campaign for the closure of Guantánamo. If viewers outside the UK have difficulty accessing the broadcasts, there are clips from the BBC interview on Twitter here, here and here.

Please also feel free to listen to me on BBC Radio London this morning. The section on Shaker began at At 01:06:27, and my interview started at 01:08:26 and finished at 01:15:10. A good interview, I thought. Please have a listen, and share it if you agree. And please also free to check out my interview with Wandsworth Radio, recorded in the evening.

Shaker Aamer speaks about Guantánamo

Remembering brutality in Guantánamo, and recalling, in particular, the approach of the Forcible Cell Extraction team, six armored soldiers, empowered to suppress, with violence, any perceived infringement of the rules, Shaker told David Rose, “You feel scared.” In Shaker’s case, FCE visits to his cell were shockingly regular, and as he said, “You know you can get hurt, because there are some huge guys there, 18, 20 stone guys, muscular. You could be paralyzed. Anything can happen. Anything.”

As the FCE team arrived, Shaker was sitting on his bed. He recalled, “The watch commander screamed: ‘239, get down on your face, do not resist!’ But, as usual, I was not going to lie down, because the cell is so small that if you lay face down, you stick your face in the hole which is the toilet.”

Nevertheless, the FCE team, using their riot shields, forced him to the ground. “It’s like a train hitting you,” Shaker said, adding, “You are already breathing hard and they are on top of you. They lift you up and press their shields against you so your body is like the meat in a sandwich.”

And all the while, the FCE team members scream. Shaker said, “They only shout one thing, ‘Stop resisting’. I was not resisting at all — how could I?”

“Bizarrely,” as Rose noted, “the whole incident was being filmed, because the camp has to provide a ‘combat cameraman’ for all FCE actions,” making videotapes that, in one prisoner’s case, a judge has ordered to be released to a number of media organizations, to the consternation of the authorities. As Shaker explained, “It’s ‘combat’, because to them, this is a war — the cameraman is going to war. All the time they are shouting for the camera’s benefit, ‘Stop resisting, 239, stop resisting.'”

As Rose noted, after they had “dragged him out of the cell, and flipped him backwards and forwards on the dirty corridor floor, searching him under his clothing,” they “released him, and, bruised and battered, he was locked again in his cell.”

And the trigger for this incident? An apple stem. “Before I was in Guantánamo,” Shaker said, “I always carried a toothpick. They wouldn’t let me have one, so I thought, I’ll keep the stem of an apple, and use that.” An apple had been included with the prisoners’ dinner that night, but after a guard asked Shaker to give his stem back, he explained, “It was in my mouth. I refused. I said I need it to pick my teeth. But apparently, this apple stem was going to affect the system. It cannot be allowed.”

However, despite the violence, Shaker noted that the FCE team failed. As they were walking away, he said, “I called to them through the hatch: ‘Come on, why didn’t you take it?'” — and he then stuck out his tongue to show that the stem was still in his mouth.

In his 13 years and eight months in Guantánamo, Shaker estimates that he was the victim of the FCE team on many hundreds of occasions. In 2012 alone, he said, he was FCE’d 370 times.

The last occasion came just two months before his release, because, as David Rose put it, “he refused to give four vials of blood, demanded on the spurious grounds that the authorities were checking inmates for tuberculosis.” My coverage of that, which partly led to the launch of the Fast For Shaker campaign, just before Shaker’s release, is here.

As Shaker told David Rose, Guantánamo “has been built for one purpose — to destroy human beings. There actually used to be a sign on a wall that said ‘Rodeo Range’. A rodeo is where you break horses. There you are trying to break human beings, you are trying to make them like horses.”

As Rose also explained, “What makes Aamer remarkable is his consistent refusal, year after year, to give in to this pressure — to try to maintain some semblance of control over his life, even if this amounted to nothing more than keeping an apple stem to pick his teeth. His defiance, he admits, probably delayed his release. It was also how he survived, and clung to his sanity.”

As he also noted, “Aamer was in Guantánamo for so long that it is impossible to provide a complete narrative.” Then again, as Shaker told him, “There is no such thing as Guantánamo in the past or Guantánamo in the future. There is no time, because there is still no limit to what they can do. What they did ten, twelve years ago, they can do it today. Who is going to stop them?”

After arriving during the days of Camp X-Ray — the outdoor cages, like animal pens, which are now closed and overgrown — Shaker spent only a few days, in his entire 13 years and eight months at Guantánamo, in Camp 6, built in 2006, which is for prisoners viewed as compliant, who “are allowed out of their cells for ten hours a day, to eat together and play sports.”

He spent much more time in Camp 5, described by Rose as “much more Spartan: there, inmates spend 23 hours a day locked up, taking bland, tasteless meals in Styrofoam ‘clam shells’, with just an hour for a shower and outdoor recreation.” Shaker told him that “one of the most unbearable aspects of Guantánamo” for him was that “Camp 5 was close to the soldiers’ kitchen, from which he inhaled the delicious smell of barbecued meat three times a week, yet was never given it.”

Shaker also “spent many months in solitary confinement” in Camp Five Echo, the prison’s isolation wing. Sometimes, he explained, he “had access to books,” and one of his favorite books was George Orwell’s 1984, which, as Rose described it accurately, is a novel “about torture and dictatorship,” and unusual for being a book of relevance to Guantánamo that made it past the censors. At other times, he explained, “he was deprived even of this: weeks and months when the days became a sterile, meaningless blur.”

He also explained that “[t]here were also interrogations — ‘appointments’ as they were called.” Over the years, Shaker said, “he had about 200 interrogators, all repeating the same questions he’d already been asked in Afghanistan, along with allegations about his supposed — and hotly denied — recruitment for jihadi groups in London.”

He added, as Rose described it, that “appointments” were often “accompanied by torture: sleep deprivation; being left shackled to the floor in a room colder than freezing point, for up to 36 hours at a time; being bombarded with continuous, deafening rock music.”

“The cold temperatures: my God, that was terrible,” he said, adding, “They just leave you, tied to a ring in the floor: sometimes the interrogator doesn’t even come. You shout, you bang, you scream. They don’t let you go to the toilet: if you need it, you go on yourself. And nobody bothers about you, that’s it.”

According to US personnel who have spoken about Guantánamo before, these techniques, disturbingly, were applied between 2002 and 2004 to around a sixth of the men held; in other words, at least 100 prisoners. And for some, the worst aspect of the torture program was what was euphemistically named the “frequent flier program,” when prisoners were moved every few hours from cell to cell, for days, weeks or even months, as a technique for sleep deprivation.

In the spring of 2005, as Shaker put it, “he decided he’d had enough.” As he said, “I just stopped talking to the interrogators. I refused to answer any more questions.”

Soon after came the biggest mass hunger strike in the prison’s history, which, Rose noted, was “led by Aamer, though he had been in solitary for months. Using a fork to scratch away the glue around his cell window, he broke the soundproof seal, allowing him to shout to prisoners in the recreation area outside. Shaker said, “I called out, ‘Who is outside? and then we transfer[ed] information.”

The news, as Rose put it, “spread from corridor to corridor, and then, inadvertently, the authorities gave Aamer a chance to disseminate it further,” when he was subjected to the “frequent flier program,” which had evidently not stopped in 2004, but which “allowed him to contact more inmates.”

Shaker said, “I remember the day my weight dropped below nine stone, when I’d been on hunger strike for almost two months. For days, I’d also refused water. I was less than half the size I had been when I was taken prisoner. I saw myself in the mirror. I started laughing, because I was so skinny. Then I remembered my wife, Zin, and I was crying at the same time. I saw her in front me, falling down and dying because of the way I looked: nothing but bones.”

He added, “They took me to the hospital and put me in a wheelchair, because I couldn’t walk. They wanted to give me a ‘banana bag’: intravenous fluid with potassium and glucose. Seven times the nurse tried to give me an I/V, but he couldn’t find a vein. He said, ‘this guy has to drink water, he is so dehydrated we cannot stick a needle in him.’ The colonel, Mike Bumgarner, came. He goes, ‘come on, Shaker, please don’t do this to me. Take a bottle of water.’ I said OK, and I drank.”

The date, David Rose noted, “is engraved in Aamer’s memory: July 27, 2005.” He added. “It was the closest he had come to death. But it was also a turning point. Fearful the strike would become unmanageable, Bumgarner negotiated with Aamer, who then took charge of what became known as ‘the Shaker government’ — a committee of six prisoners who were allowed to move, handcuffed and under escort, throughout the camps. The idea was to sound out opinion, to look for ways to ease the tension in ways acceptable to both the authorities and inmates.”

As Shaker said, “I was trying to get them to agree to fulfil the Geneva Convention.” However, as Rose noted, “That proved impossible, and on August 8, the experiment ended — with Aamer back in solitary.” For more information on the strike, see Tim Golden’s 2006 article for the New York Times, “The Battle for Guantánamo.”

Meanwhile, as Rose put it, Shaker “had made a surprising discovery. It was already known that some prisoners were being given exceptional privileges for ‘snitching’ on other inmates, such as trips to the ‘Love Shack’, where they would be given hamburgers and shown pornographic videos. Indeed, Aamer says that his interrogators made three futile attempts to recruit him.”

He explained, “We had heard rumors that there were detainees who were paid to infiltrate Guantánamo. These guys were doing a job. One is to infiltrate. Two is to spy, to hear. Three is to cause issues between the brothers. Four, to report of any kind of grouping.”

After the hunger strike, Shaker came to believe that the rumors had to be true. He said, “I had cruised around the camps and I had counted everybody. I went into every camp, and I knew how many cells there were in each one.” However, although, at this time, Guantánamo’s official prisoner total was 530, Shaker is convinced that “there were dozens more — all of them, he presumes, what he calls ‘hired prisoners.'”

When ‘the Shaker government’ collapsed, Shaker spent his longest period in solitary confinement — almost two years, way beyond the acceptable amount of time that anyone should held in solitary confinement.

During this period, Shaker was approved for release from Guantánamo, as he was again in 2009, by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that the new president, Barack Obama, established shortly after taking office in January 2009.

Even before that decision was reached, however, Shaker was supposed to have been released. Speaking of the release, in February 2009, of the British resident Binyam Mohamed, Shaker said, “I was supposed to be on that aeroplane”

Instead, as David Rose described it, “an officer said he might be sent to Saudi Arabia. He says he was ready to agree, provided his wife and children could join him, but as soon as he raised this issue, the offer was withdrawn.”

In Britain, however, “demands to free him were gathering strength.” In their regular visits to him Shaker’s lawyers, led by Clive Stafford Smith of Reprieve, told him about the support he had from MPs, newspapers and campaigns — both the Save Shaker Aamer Campaign and We Stand With Shaker.

At this point, he told David Rose, his morale “was ‘like a candle’ that could have blown out.” As he said, “You guys protected it. All those who fought for justice for me, who joined in those protests — I can never thank you enough.”

And yet, even at the end, Guantánamo “stuck to its protocols.” Shaker’s “last argument with a guard came just an hour before he left the camp, when he was told he could not shout goodbyes to other inmates. When he got on the bus that was to take him to the ferry across Guantánamo Bay, the way to the airport, it had blacked-out windows. Going straight to the jetty would have taken five minutes, but he was driven around in circles for two hours, apparently so he would not get an impression of the camp’s layout — even though this has been visible on Google Earth for years.”

“But at last, Rose added, “his ordeal was ending. In the middle of the hot, Cuban night, he stood on the airstrip tarmac, his hands bound with plastic cuffs. Shaker said, “I think I am the only detainee for whom the colonel himself, David Heath, came and cut the cuffs off my hands. He looked at me and said, ‘You are a free man’. That was a beautiful moment.”

Recalling a low point in his 13-year ordeal in Guantánamo, Shaker also spoke about how his interrogators had tried to bribe him to make a false confession with photos of his children, which is cross-posted below:

Any long-term prisoner with a wife and family will find separation painful. But for Shaker Aamer, the deep isolation of fortress Guantánamo made this agony far worse. All forms of intimate communication were impossible in the jail. The rare letters the authorities allowed were censored and strictly monitored.

Aamer’s wife Zinneera sent him family photos, only for his interrogators to use them as a weapon: ‘They refused to give me my kids’ pictures for years, but they put them on the walls in the interrogation room. Imagine if you did not see your kids for four or five years, and then one day they take you in for interrogation.

“I go inside and I see pictures all over the wall, big pictures, small pictures, everywhere. I will not forget that day, because I left them when they were little kids, and I could see they had grown up. They wanted to break me down, and they told me, if you want your kids’ pictures, you have to talk to us.” But this meant one thing — to confess to terrorist crimes he had not committed.

Aamer refused, insisting as ever he had done nothing wrong, and that he had no information that could help the fight against terrorism. Eventually, “guards came to pick me up. I went and kissed the pictures by the door. The guard asked me why I was doing that, and I told him: ‘these are my kids, and they refused to give me their pictures.'”

One day in 2009, after more than seven years in Guantánamo, Aamer was told without warning he had a phone call: “They wouldn’t tell me who, but they said it’s really something important. I thought my mother had died. I sat down in a room and they gave me the phone and then I found it was my wife. I thought she would be crying, but actually I was the one who was crying. I was crying like a baby on the phone, truly. I also spoke to my daughter Johaina and I was crying with her, too. A lot of men are too scared to cry because they think crying is weakness. I don’t believe that. When these tears come out, I think it’s your heart, it’s what makes your heart alive.”

In 2012, the family was allowed the first of several video calls, using Skype. Aamer cried then too: “I can barely describe what I was feeling. It’s happiness mixed with fear, mixed with anger, mixed with everything. Love and hate together.”

Life after Guantánamo

Below is an edited version of Shaker’s thoughts about his freedom and being reunited with his family, published under the heading, “Joy I dreamed of for 14 years: From hell to ecstatic reunion.”

David Rose began by writing about his return to the UK, when he arrived at Biggin Hill Airport at lunchtime on October 30. “I was in the aeroplane, talking to a policeman and someone from the Home Office,” Shaker said, adding, “But still there, in the back of my mind, I was wondering: is it really true, is it really going to be England, am I really going to be meeting my family?”

He told David Rose that he still feared “that small percentage of possibility that it could have been a trick — it could be Saudi Arabia, it could be anywhere.” Rose noted how he was “used to disappointment,” and “was still reflexively trying to protect himself.” In Shaker’s words, “Just in case. I didn’t want to be shocked, I didn’t want to be surprised.”

However, as the plane descended, Shaker “gazed through the window at an unmistakeably English landscape of green chalk downs and autumnal woods,” and “felt confident.” He said, “We landed and at last I was sure: I saw England. And I thought, my God. I really am back.”

As the plane door opened, “he was struck by the deliciously cool and damp English air: weather very different to the tropical heat of Guantánamo,” as David Rose described it. Shaker said, “As soon as they opened it [the door], I said to the Met officer next to me: ‘That is my first breath of freedom.’ Everything looked British. I was overwhelmed.”

As Rose described it, “His emotions were in turmoil. Although he had known for several weeks he was finally set for release, he hadn’t been told when he would leave Guantánamo. When the day finally came, he was given just an hour to take a shower, gather his meagre possessions and prepare for the journey ahead.”

“I walked down the steps, and I was just so happy, because I knew I really was free,” Shaker said, adding, “Yet I also felt apprehensive. I was worried that they might take me somewhere to ask me questions. But the Home Office guy who had come to meet me had this huge smile on his face. Everybody was telling me, ‘welcome back’, the officials, the one who came with the fingerprint stuff, they were actually happy to see me … they had tears in their eyes.”

Next came “an exhaustive medical check-up” and then the reunion with his family. On that first evening, as David Rose described it, “he was finally re-united with his wife, Zinneera — though not yet his children — in the privacy of a friend’s London apartment, so no one would know where they were.”

Shaker said, “At last that moment I’d dreamt of came and she came through the door. That instant washed away the pain of 14 years. It washed away the tiredness, the agony, the stress. It was like it no longer existed. I hugged her, she hugged me, and we just wept. I stayed with her that night and we couldn’t sleep actually, we were just talking and talking. I was scared to meet the kids at first: I told her, I just wanted to be with her because I needed to know who these kids are — I can’t just see them, I don’t want to do something that will make them fear me. So I saw Zin only. She reassured me. She said, ‘Don’t worry, they are very strong kids, they are very beautiful kids.’ I asked her about who they are, how they feel, how they do things, and we kept talking about them all the next day, morning till night. And then, in the evening, they came.”

David Rose wrote that his first meeting — with his daughter Johaina, who had just turned 18, and his sons Michael, 16, Saif 15, and Faris, 13, who was born on February 14, 2002, the day his father arrived at Guantánamo — was “awkward.”

“I just wanted to hug them and kiss them,” Shaker said. “But they were standing stiff. It tore my heart. They are shy kids to begin with. But they were looking at me and looking away. It was hard.”

However, after he returned to the family home in Battersea, “the distance between them melted away,” as David Rose put it. Shaker said, “The week after I got home, I made a barbecue in the garden, even though the weather was a little bit cold. They loved it: they could see I hadn’t lost my touch as a chef. Now I’m a hard-working man at home, doing the dishes, cleaning the house, and I love cooking for the kids. We’re getting used to each other. I take them to the mosque. When the weather gets better, we’re going to get bikes, go on weekend rides.”

A few weeks later, David Rose met Shaker and his family at Bicester Village, a shopping mall near Oxford, which, as he put it, was Shaker’s “first family outing for 14 years.” He said, “I’m finally living. I’m here with my kids, trying to learn to be a father.”

His sons, Rose noted, “were staring at their smartphones — new models brought as gifts by Shaker’s nephew, who was visiting from Saudi Arabia.”

Shaker also had a smartphone, but admitted, “I haven’t mastered it yet. Not even one per cent of what it can do. This is one of the biggest changes since I went away. People spend so much time looking at them!”

He also mentioned other changes he had noticed. “London seems richer: when you see all the new buildings, the cars,” he said. “And the people are different, too. Before, when you walked in the street, you heard only English being spoken. Now if you go out, you will hear ten or 15 languages, from Eastern Europe, China, everywhere. London is truly becoming a cosmopolitan city.”

Faris, who “loves to sketch buildings and would like to be an architect,” told David Rose about the moment he saw his father for the first time. “It was so amazing,” he said. “Even now, my senses are telling me that he’s back, but in my brain, I still can’t believe it. When I was younger, I used to think he might possibly never come back. Yet now he’s here.”

Shaker, speaking of that first meeting, said that when he first met Faris, “I told him, I don’t expect you to love me straight away. I just want you to trust me, because it’s hard to love someone when you don’t know them.”

Michael, who was just two when his father was first detained, said, “I have no memory of him then. Mum used to tell us that our dad was in school, but his teacher wouldn’t let him come home. Then one day a letter came from Guantánamo. My sister read it and we started researching what was happening on the internet. That’s when it hit us that he was a prisoner, that he was gone, and that he might never be coming back. There were a few times when we thought he might be coming, but he didn’t. But when other detainees were released, I was happy, because I felt he might be next.”

Rose also noted that Shaker said that freedom “has brought other, simple joys: above all, something almost everyone takes for granted” – that of “being treated like a normal human being.”

Shaker said, “A few days ago, I was with my daughter, using our Oyster cards to go through the gates on the Tube, and there was this guy in a wheelchair. He asked me for help, to push him to the bus station. He was a clean-shaven white guy and I’m an Arab with a beard. I said, ‘Of course I will help you, and I’m so happy you asked me.’ It was a little bit uphill and I pushed him all the way and I was talking to him. Fourteen years I’ve been controlled, 14 years I haven’t talked to a normal human being, and here is somebody who will talk to me, who isn’t scared. I was so happy because I felt like, yes, this is it, I’m back.”

Shaker recalled another occasion, when he went to open a bank account. As he sat with a member of staff, filling in the form, he said, “And then we came to, ‘OK, Mr Aamer, where did you live three years ago?’ I said I was living in America. He said, ‘Beautiful, for how long?’ I said for the past 14 years. He goes, ‘OK, could you please give me the address?’ I’m not going to lie to my bank, so I looked at him and I said, ‘I was in Guantánamo for 14 years.’ His response was shocking. I thought he was going to say, ‘Can you wait a minute I need to speak to my manager.’ Actually he just took my hand and said, ‘I am honoured to talk to you.’ He said, ‘Listen, just come here anytime if you need any help.’ That’s what makes you happy: an average, normal person in the street who knows you have really had a great injustice, but now they are going to try to help you.”

Shaker also spoke about his difficulties knowing how to act as a father, mentioning one night when he found his sons still on their phones after being told that it was time to sleep. “I said, ‘Guys, please, don’t make me take all these phones away.’ My fear was they would think, ‘He’s a stranger, why should he do anything to us, why should he take our things?’ I don’t want to do something that makes them hard for them to accept me. I feel I am walking on eggshells here. I don’t want them to think, ‘This guy came only yesterday and now he is controlling everything.'”

He decided, however, that the best response “was to talk to the children, to explain his difficulty.” He told David Rose, “I said, ‘Listen guys, I need you just as much as you need me, I’ve been 14 years away and I did not practise my fatherhood, so please let me.’ I told them, ‘Talk to me, or send me a letter if you cannot talk about something.’ I gave them an example: if you see a girl and you think you like her, tell me, don’t be shy, because that’s normal, that’s your age, and I will explain to you what’s the difference between love and just when you’re a teenager.”

He also said that “he feels they are all making progress,” as Rose put it, and he spoke about Michael, saying, “yesterday I’d been out and when I came back home, he opened the door and he hugged me. I said, ‘Your mother told you to do that,’ and he said, ‘No, no, I want to do it.’ I was so happy because he really hugged me himself, he wants to do it.”

Shaker also said, as David Rose described it, that “he recognises he will never get over Guantánamo entirely,” because “the wounds run too deep.” As he said, “It’s always going to be in the back there in my mind, it’s going to be sitting there, coming back from time to time. It’s a long period of experience and it can’t be just gone.”

Rose also noted that it was clear that Shaker is “just as determined to rebuild his life as he once was, not to be broken by torture.” He said, “You cannot forget it, but you try to seal it, and put it where it’s not really bothering you. The way I grew up with my family, we give trust a lot, and you have seen me, you know me by now, I trust people still. You get along much better if you do. You can’t live your life being careful, having doubts about everything. You must embrace it.”

December 13, 2015

Shaker Aamer Speaks: First Newspaper Interview Since Release from Guantánamo, in the Mail on Sunday

The Mail on Sunday today featured the first interview conducted by Shaker Aamer since his release from Guantánamo six weeks ago, and below are excerpts dealing with his life from 1989 to February 2002, when he arrived at Guantánamo, providing information not previously discussed — in particular, about the circumstances of his visit to Afghanistan and his capture.

The Mail on Sunday today featured the first interview conducted by Shaker Aamer since his release from Guantánamo six weeks ago, and below are excerpts dealing with his life from 1989 to February 2002, when he arrived at Guantánamo, providing information not previously discussed — in particular, about the circumstances of his visit to Afghanistan and his capture.

Speaking to David Rose, Shaker spoke about his experiences in the US after he left Saudi Arabia, where he was born in 1966, in Medina. From 1989 to 1995, he explained, as Rose noted, that he “lived mostly in Atlanta, in the US state of Georgia, working as a chef in restaurants. In those days he lived a Westernised life: a lover of rock music, he often attended concerts by his favourite bands — including AC/DC and Ozzy Osbourne. In this period, in 1990, he responded to a US army recruitment drive for Arabic/English translators during the first Gulf War — which is how he came to find himself working for the US infantry in Saudi.”

“First I was in the south, then at a base in Tabuk, near the Jordanian border,” Shaker said, explaining that he needed security clearance for the job. “Of course I had to be checked. I was right inside the US base. I got to know those guys very well, especially the colonel — his name was Johansen. Later, I used to tell my interrogators: call Colonel Johansen, he will tell you I’m not a terrorist, that I’m a good guy, and that I’m telling you the truth. I’m sure they never did.”

I’m sure they never did either, as the US authorities were notorious for failing to follow up on any request by prisoners to contact people who would vouch for them — as I made clear in February 2008 in a front-page story I wrote for the New York Times with Carlotta Gall about just one of the many men this happened to, Abdul Razzaq Hekmati, an Afghan who had helped to free a number of prominent opponents of the Taliban from jail, but died of cancer at Guantánamo without the authorities ever checking his story, as he repeatedly requested.

In 1996, Shaker moved to London, where he met and married Zinneera, a British citizen. He worked as a translator for law firms dealing with immigration issues. However, as David Rose described it, they “found it impossible to raise enough money to buy a house.”

Shaker said, “We ended up staying with friends or with my father-in-law. For four years, we were basically homeless.” He decided to take Zinneera and their three young children to Saudi Arabia, to start a new life, but had problems getting a visa for his wife. It was then, in July 2001, that Moazzam Begg, a friend who ran a Muslim bookshop, “came up with a plan to set up home in Kabul instead, to do development work in rural Afghanistan,” as David Rose put it. They “planned to set up a school and provide water supplies.”

Shaker said of Afghanistan, “There is a great shortage of wells, so people have to walk miles just to get water. Yet it only costs £200 to make a well for a village of 3,000. That is a beautiful thing.”

Rose asked Shaker why he would go to to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, to which he replied, “Do you think I saw 9/11 coming? Of course not! I was just a guy who had spent the previous five years taking care of his wife and children. It wasn’t that I thought the Taliban had created some perfect society, but I thought that there, we could have a better life, and do some good. At that time, the UAE, Qatar, Pakistan, the Saudis all had embassies in Kabul. There were British businessmen who were setting up a mobile phone company, investing millions; all kinds of business was starting to boom. I had German neighbours, who like me felt the country needed help — but no one took them to Guantánamo, because they were Europeans. Going to Afghanistan does not mean I was a terrorist.”

Shaker then explained that, for a period of just a few weeks, the two families enjoyed living in Afghanistan. “We were living comfortably, in a big house with a garden, because there it is so cheap,” he said. Then 9/11 happened, wose significance, he said, he did not, at first, recognize. But as the US prepared for war, Shaker and his family, like all the foreigners in their neighbourhood — an upmarket part of Kabul — were told to leave.

Shaker said, “The Taliban came to each house and said you have got to get out of here, this is an order.” However, as Shaker explained, they did not know how to leave. By October, when the US-led invasion began, “Afghanistan had become a bloody and confusing war zone,” as David Rose said, but “[t]hey had a car, and took to the road, trying to survive bombing raids and to find a way to Pakistan, staying on the move for a month. Later, Aamer would face claims by interrogators that he took part in the fighting; that he carried a 75lb mortar. All this, he said, is lies — the product of confessions by other prisoners who were tortured” — lies that I partly exposed in an article in early October following the announcement of Shaker’s intended release, entitled, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Truth, Lies and Distortions in the Coverage of Shaker Aamer, Soon to be Freed from Guantánamo.”

In early November 2001, as David Rose explained, Shaker stated that “they were given shelter in a village near Jalalabad, 50 miles from the border, but the place was insecure.” Shaker said, “It was chaos, and I felt I was being hunted. US planes were not only dropping bombs but leaflets, saying the Arabs are bad people, they want to destroy your country, we don’t have a problem with the Afghani people but we want the foreigners.’ These leaflets, prepared by US PsyOps teams, offered substantial rewards for individuals involved with Al-Qaeda or the Taliban — or those who could be passed off as Al-Qaeda or the Taliban.

One day, as David Rose put it, “Shaker left the house where they were staying — without telling his family — to look at a new place of refuge, where he had been promised they would be safer.” However, when he got back to the village, Zinneera and the children had vanished. As Rose stated, “He was told they were being taken to Pakistan in the company of friendly locals, but had no way of knowing if this was true.”

“It was terrible. I didn’t know what to do,” Shaker said, adding that, as well as not knowing how he would see his family again, he also feared for his life. Soon after that, “he was taken prisoner, by a gang led by another village leader, with whom Shaker is still understandable angry. “One day I will go and see that bastard, because I trusted him,” Shaker said, adding, “I gave him my family’s phone numbers in Saudi Arabia, and I said, if you ever go there you can visit my brother, my family will help you.”

This village leader “demanded money, which Aamer no longer had.” As a result, he “presumes that he — like hundreds of those held at Bagram and later Guantánamo — was ‘sold’, for the bounty promised by the US leaflets. The going rate was $5,000. He was taken first to Jalalabad, then Kabul. Finally he was taken by the Americans.”

Speaking about when he first heard American voices, he said, “I was so happy, because before that, I thought I am going to get killed. A chopper came down and landed, and there were five Americans, and I said, wow, that’s it, they’re going to call Britain and find out who I am, and send me back to England.”

Instead, as David Rose described it, he “was taken in the helicopter to Bagram, and when he disembarked, he was herded into a pen and made to sit on the ground.” As Shaker put it, “I am sitting there relaxed, with a smile on my face, because I’ve got to safety, and it’s going to be a matter of days and I’m going to be back again with my wife. That’s when they said, ‘Take your clothes off.’ There were so many people in front of me, females and big hefty guys, people with guns. I said no. One of them had a big, heavy stick, like a pick-axe handle, and he smashed it on the ground right next to me. He said: ‘You have to, or we’ll kill you.’ ‘I was like, s***, this is serious. I took off my underwear and they made me squat, naked. Then they made me walk around. It was just for humiliation. They gave me a thin blue overall and tied my feet and hands together with zip locks and put me in a cage.'”

Bagram was a particularly brutal place in 2002, as David Rose noted, pointing out that “US military coroners later found that two prisoners were beaten to death, and 15 guards were charged with crimes including homicide,” even though most were found not guilty. I wrote about these and other deaths in an article in July 2009, “When Torture Kills: Ten Murders In US Prisons In Afghanistan.”

Speaking further about Bagram, Shaker said, “They used to step on my face, they used to jump on my face with their boots. Imagine in the freezing cold winter, on concrete in the middle of the airport, and young guards are beating you, they beat the hell out of you with their M16s, and jumping on your face and your body with their boots. These guards were doing it as a systematic torture. Every time somebody arrived, they had to beat the s*** out of him, to make him know that if he does anything wrong, if he tries or thinks of running away he will never make it.”

Shaker told Rose that he “was deprived of sleep for days, made to stand with arms outstretched — another US-authorized technique, known as a ‘stress position’. Twice, he said, he was left alone in an interrogation room with a loaded gun on the table.” As he asked, “What do you want me to do with a gun there? Either I take the gun and kill myself, or I take the gun and as soon as I do you put a bullet in my head.”

He also explained that US Marines “had laid a wooden floor in the cages and hangars, which provided insulation from the sub-zero temperatures. But after a few days, they took all the wood out, leaving bare concrete.” Shaker said that he “had no shoes, and developed frostbite.” Pointing at Rose’s black laptop bag, he said, “My feet were darker than this colour. I didn’t think I would survive.” As a result, to this day “he has to wear two layers of thick ‘pressure socks’ to stop his legs and feet filling with fluid and swelling like balloons.”

As Rose explained, “The risk of infection was serious,” but, as Shaker said, “they didn’t give me antibiotics, not even paracetamol. Then they moved me out, they said I had to walk to another building. I felt like my feet were going to blow up. Pain, pain, pain. I had to walk because otherwise, I will get beaten.”

He also pointed out that he was “doused with iced water.” As he said, “They have a raku, you know, an Afghan hat, and they fill it with freezing cold water and then they stick it on your head. You are soaked, from your head to your legs, and you are freezing.”

Because of this, he said that “although he had initially denied any involvement with terrorism, he was soon ready to agree to anything.” He added that “he cannot remember exactly what he said, because by this time he was hallucinating, and his memory is hazy.” However, he remembered that on one occasion he said, “You know the Second World War? Do you know what’s behind it? I am. I am behind the Second World War.”

He added, “I’d already told the truth, that I was not a terrorist, but he [the interrogator] wouldn’t accept it. So that’s what I said. They torture you for the torture itself, regardless of what you tell them. People don’t understand, they were not looking for anything, they were looking for a black sheep, a scapegoat.”

It was at Bagram, where he was known as detainee 005, that, “just before 11pm on January 7, 2002,” he “dared to hope,” when a guard told him that Tony Blair was arriving that night. As Rose put it, “He believed if someone in Blair’s entourage saw his desperate condition, they would help him. They could reassure the Americans he was no terrorist.” However, although he “met three British plain-clothed officials who he believed to have arrived on Blair’s flight,” they were not there to help him, even though he “had lost weight, had frostbitten feet, and bore bruises from repeated beatings.”

Shaker said, “The first British guy said his name was John; he said he knew about me from London. He told me openly he was from MI5, and that he had a file on me. But the first thing he said when he saw me was, ‘Shaker, you look like a ghost.’ With the torture, with the beating, I didn’t even know what I looked like. I hadn’t seen my face in months.”

However, “‘John’ did nothing to assist him. Worse, later in the course of the British officers’ visit, Aamer said, one of John’s colleagues was present in an interrogation room when he was subjected to the torture known as ‘walling’ — having his head smashed against a wall while he sat shackled in a chair. The Americans called this an ‘enhanced interrogation technique’, and though it was never approved for use by British officers, it had been authorised by the Bush administration.”

Shaker added that, inside the interrogation room, “They were shooting questions without listening to answers. ‘You did this or that, why did you do that, where did you go.’ “They were accusing me of fighting with Bin Laden in the battle of Tora Bora; of being in charge of weapons stores; of being a terrorist recruiter – though I’d only been in Afghanistan for a few weeks. I start to try to talk but everybody is just shouting and screaming around me. Then suddenly I feel it — douff — this American guy grabs me by the head, and he slams it backwards against the wall. In my mind I think I must try to save my head so I tried to bring it forwards, but as soon as I do he grabs it again and bashes it: douff, then back again, douff, douff, douff.”

Shaker said that he didn’t completely lose consciousness, but “I was completely disorientated. So I sat like this, dizzy and disorientated, my eyes shut, and the guards moved me back to the cage.” The British officer who saw this, he said, had a “posh English accent, a very white guy with blond hair,” but he “did nothing to object or intervene.” The article added that further details of “alleged complicity by UK personnel in [his] ill-treatment” cannot currently be published, because of Shaker’s current lawsuit against the British government.

Three weeks after the British visit, Shaker “was flown to another US base at Kandahar, where the abuse continued, and then, after a further fortnight, he was put on the third detainee flight to Guantánamo. As he said, “My number was five at Bagram, 449 in Kandahar and 239 in Guantánamo.”

Describing what Shaker had said about the journey to Guantánamo, David Rose stated, “The seemingly endless journey, spent shackled, dressed in orange overalls and an adult nappy, blindfolded and unable to hear through ear defenders, was horrific.” He also noted, “Before it started, he had been forced to shower, naked again in front of soldiers with vicious dogs. He had his beard and head forcibly shaved, and had been sprayed all over with insecticide.” As he said, “I just accepted everything. What could I do? I knew if I said something, I was going to get bashed.”

Nevertheless, as he told Rose, he “felt optimistic.” As he said, “After so much fear and torture, I thought that when we got to Guantánamo, that would be the end of it.”

The next 5,000 days, however, would prove how wrong that assessment was.

See more — about Shaker’s experiences in Guantánamo, and his reunion his family and his efforts to readjust to civilian life in the UK — in an article to follow.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

December 10, 2015

On Human Rights Day, A Call for the US to Close Guantánamo, and for the UK to Defend the Human Rights Act

Please support my work!

Over 60 years ago, in the wake of the horrors of World War II, when people with power and influence were determined to do whatever they could to prevent such barbarity from taking place again, the United Nations was established, the Geneva Conventions were rewritten, and representatives of 17 countries drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly exactly 67 years ago, on December 10, 1948. Human Rights Day itself was established 65 years ago, on December 10, 1950.

A powerful attempt to establish “a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations,” the UDHR set out, for the first time, and in 30 articles, fundamental human rights that were to be universally protected.

These include protection from torture and “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment,” protection from “arbitrary arrest,” and the right to “a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him.” The UDHR also stated, “Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.”

I mention these articles in particular (Articles 5, 9, 10 and 11), because they seem very much to apply to the US prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, which is still open nearly seven years after President Obama first declared that he would close it within a year. A legal, moral and ethical abomination, Guantánamo is still used to hold people without proper rights. For the most part, the men still there (currently 107 men) are held indefinitely without charge or trial, even though holding people indefinitely without charge or trial isn’t supposed to happen in countries that claim to respect the rule of law, and the only acceptable way to deprive anyone of their liberty is as a criminal suspect, or as a convicted criminal after a trial, or as a prisoner of war, protected by the Geneva Conventions.

Some years ago, the BBC World Service ran a feature on the UDHR, with links to each of the articles, choosing Guantánamo for Article 10, Right to fair public hearing by Independent tribunal, and last year Vice News published the Universal Declaration of No Human Rights, written by Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, which I cross-posted and wrote about here.

Last December, We Stand With Shaker, the campaign I co-founded with Joanne MacInnes, worked with students in London to make a film featuring excerpts from Shaker’s Universal Declaration of No Human Rights, featuring Juliet Stevenson and David Morrissey, and I’m posting that video below as a reminder of how disgracefully human rights have been jettisoned at Guantánamo.

What you can do now

To remind President Obama of the need for Guantánamo to be closed, call the White House on 202-456-1111 or 202-456-1414 or submit a comment online.

Save the Human Rights Act

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was the inspiration for the European Convention on Human Rights, drafted in 1950 by the Council of Europe, founded in 1949, which promotes human rights, democracy and the rule of law in its member states (10 originally, and now 47, representing 820 million people in total). In turn, it led to and led to the establishment of the European Court of Human Rights.

It’s important to note that the Council of Europe is an independent body, and is not to be confused with the European Union, although membership of the Council of Europe is a requirement for EU member states.

An offshoot of the ECHR, in the UK, is the Human Rights Act, which, as Bella Sankey, Liberty’s director of policy, explained in a recent article for the Huffington Post, “was passed in 1998 with overwhelming cross-party support and Tory leadership endorsement,” and “was a long-held ambition of the Society of Conservative Lawyers.”

Now, however, the Tories under David Cameron want to repeal the Human Rights Act, an act of idiocy, intended to pander to tabloid editors and the vindictive streak that runs through the Party, unchallenged, largely to suggest — wrongly — that we can and should be free to deport whoever we want, under any circumstances, when our leaders want (in the cases of alleged terror suspects, it should be noted). In fact, the HRA is essential for all of us, because it protects us from abuse by the state.

As Liberty states:

Our Human Rights Act protects every one of us: young and old; wealthy and poor; you and your neighbour. Our HRA has already achieved so much. It’s held the State to account for spying on us; safeguarded our soldiers; and supported peaceful protest. It’s helped rape victims; defended domestic violence sufferers; and guarded against slavery. It’s protected those in care; shielded press freedom; and provided answers for grieving families.

My in-depth analysis of why the Tories’ plan to repeal the act — and replace it with a British Bill of Rights — is so stupid was published back in May, just after the General Election. My article wa entitled, “What Does It Say About the Tories That They Want to Scrap Human Rights Legislation?” and in it I wrote the following about how, in order to repeal the HRA, we would need to withdraw from the ECHR:

[W]ithdrawal from the Convention would mean withdrawing from the Council of Europe, and … EU membership requires CoE membership. Are we to see a ridiculous situation whereby a referendum on leaving Europe, which David Cameron doesn’t even want, goes ahead and is promoted by the Tories, with ruinous effects on British business, simply because the Tories don’t like some of the minor constraints on their actions that are enshrined in human rights legislation?

To understand quite how ridiculous this is, it’s worth pointing out how the current situation actually gives the UK more, not less influence over the European Court of Human Rights — providing yet more confirmation that the Tories’ plans are idiotic, designed to appeal to legally illiterate right-wingers, and demonstrating how much this particular batch of Tories hates being told what it cannot do.

On Human Rights Day, Shadow Human Rights Minister Andy Slaughter and Shadow Foreign Office Minister Diana Johnson have written an article for the Daily Mirror, stating, “Michael Gove should celebrate Human Rights Day by dropping plans to scrap the Act.” The Guardian reported on December 2 that Michael Gove has in fact delayed announcing detailed changes until next year, but that is not enough, as former Attorney General Dominic Grieve made clear in an article in June, and law professor Philippe Sands made clear in an article in October.

What you can do now

See Liberty’s pages on the HRA here, their mythbuster here, and their campaign page here. Also see Amnesty International’s campaign pages here and here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

December 9, 2015

Quarterly Fundraiser Day 3: Still Hoping to Raise $2800 (£1800) for My Guantánamo Work

Please support my work!

Please support my work!

Dear friends and supporters,

It’s the third day of my quarterly fundraiser, in which I’m asking you, my readers and supporters, to donate to support my work on Guantánamo and related issues.

As a freelance investigative journalist, commentator and campaigner, I’ve carved out a niche here on the internet over the last eight and half years, writing over 1,850 articles about Guantánamo since May 2007, and, crucially, most of this work — along with most of my media and public appearances — is reader-funded, so any amount will be gratefully received, whether it is $25, $100 or $500 — or any amount in any other currency (£15, £50 or £250, for example). PayPal will convert any currency you pay into dollars, which I chose as my main currency because the majority of my supporters are in the US.

As well as running this website without any institutional funding whatsoever, making me 100% dependent on your support, I also co-directed the We Stand With Shaker campaign, which played a part in securing the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, on October 30, without any financial support either, except for that provided by you, my readers and supporters.

So if you can help out at all, please click on the “Donate” button above to donate via PayPal (and I should add that you don’t need to be a PayPal member to use PayPal). You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make This Recurring (Monthly),” and if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (address here — scroll down to the bottom of the page), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send cash from anywhere else in the world, that’s also an option. Please note, however, that foreign checks are no longer accepted at UK banks — only electronic transfers. Do, however, contact me if you’d like to support me by paying directly into my account.

As I mentioned on Monday, when launching this latest fundraiser, it’s hugely important, with just over 13 months of Barack Obama’s presidency remaining, that those of us who want to see Guantánamo closed need to keep exerting pressure on President Obama and on Congress to try and make its closure a reality by the time the next president is inaugurated, in January 2017. I will be publicising ways in which this pressure can be exerted in the weeks to come, but for now, please check out my article, “Playing Politics with the Closure of Guantánamo.”

As I also mentioned on Monday, I really can’t do what I do without your help, and I’ll be extremely grateful if you can make any kind of donation to support me.

Andy Worthington

London

December 9, 2015

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign.

December 8, 2015

In London, Andy Worthington Discusses Shaker Aamer and Guantánamo, and His Band The Four Fathers Play Three Gigs

If you’re in London — or nearby — and interested in hearing me talk about Guantánamo and the campaign to free Shaker Aamer, and/or to see my band The Four Fathers play our mix of politically-infused rock and roots reggae, then I’d be delighted to see you at any of the events taking place in the coming weeks in south east London.

If you’re in London — or nearby — and interested in hearing me talk about Guantánamo and the campaign to free Shaker Aamer, and/or to see my band The Four Fathers play our mix of politically-infused rock and roots reggae, then I’d be delighted to see you at any of the events taking place in the coming weeks in south east London.

First up, on Saturday December 12, is a free 20-minute set at Brockley Christmas Market, on Coulgate Street, next to Brockley station, in London SE4. This is a free gig, as part of an afternoon of music to accompany the market’s plentiful stalls selling great food and drink, and arts and crafts for Christmas. We’re playing at 2pm, and amongst the other acts playing is my son Tyler, who will be beatboxing at 3.30pm.

Two events are taking place on the following Friday, December 18. First up, at 5.30pm, is a free half-hour set at the Honor Oak Christmas Experience, a Christmas event on the Honor Oak Estate, at 50 Turnham Road, London SE4 2JD.

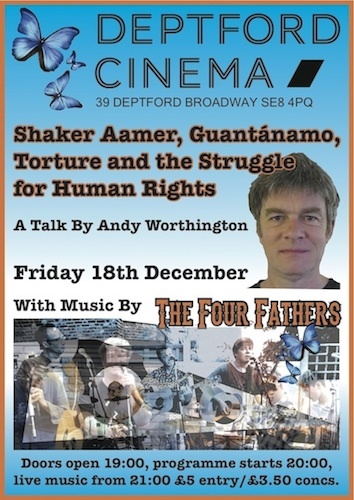

We then rush down the road to Deptford to set up for an event at the Deptford Cinema, a great community cinema at 39 Deptford Broadway, London SE8 4PQ. There’s a bar, and the doors open at 7pm, when there will be some mingling followed, at 8pm, by me delivering a talk, “Shaker Aamer, Guantánamo, Torture and the Struggle for Human Rights,” followed by a Q&A session. The Facebook page for the event is here, and if you can come, please sign up. It costs £5/£3.50 concs.

My talk will be based on my work on Guantánamo over the last ten years, and, in particular, the We Stand With Shaker campaign that I launched last November with an activist friend, Joanne MacInnes, which played a big part in securing the release from Guantánamo on October 30 of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison.

My talk will be based on my work on Guantánamo over the last ten years, and, in particular, the We Stand With Shaker campaign that I launched last November with an activist friend, Joanne MacInnes, which played a big part in securing the release from Guantánamo on October 30 of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison.

I’ll also be talking about the Close Guantánamo campaign that I launched in 2012, and which I’m hoping will play a part in working towards the closure of Guantánamo in the coming year, which, of course, is also President Obama’s last year in office.

I’ll also be talking about accountability for torture, following the first anniversary of the publication, on December 9, 2014, of the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report about the CIA torture program.

At 9pm, The Four Fathers will be playing a set including four of my political songs — “Song for Shaker Aamer,” which was used in the campaign video for We Stand With Shaker, “81 Million Dollars,” about the US torture program, and “Tory Bullshit Blues” and “Fighting Injustice,” a roots reggae anthem that deals with the need for solidarity to combat the Tories’ lies about austerity. We’ll also play our cover of Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War,” and I hope that we’ll also be able to play some new songs that I’ve written recently that we’ve been rehearsing over the last few months.

We’ll also probably be playing some of our political songs at our earlier gigs along with other covers.

Please note that our album “Love and War” is available here on Bandcamp, where you can listen to it, and buy individual songs, or the whole 8-track album as a download. You can also buy it on CD, which features two extra tracks — our covers of “Masters of War” and “I Will Survive.”

Please also follow us on Facebook, and check out our YouTube channel – and, of course, if you organise gigs and would like us to play, then we’d love to hear from you!

Please also check out my interview with Kevin Gosztola about protest music and The Four Fathers on Shadowproof and this post by Kevin making “Song for Shaker Aamer” Shadowproof’s “Protest Song of the Week.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign, the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

December 7, 2015

Quarterly Fundraiser: I’m Hoping to Raise $3500 to Support My Guantánamo Work

Please support my work!

Please support my work!

Dear friends and supporters,

Every three months, I ask you, if you can, to make a donation to support my work on Guantánamo and related issues. I’m hoping to raise $3,500 (£2,300) for the next three months, which is just $270 (£180) a week for my regular writing about Guantánamo, telling the prisoners’ stories, and campaigning to get the prison closed.

My work is primarily reader-funded, so any amount will be gratefully received, whether it is $25, $100 or $500 — or any amount in any other currency (£15, £50 or £250, for example). PayPal will convert any currency you pay into dollars, which I chose as my main currency because the majority of my supporters are in the US.

Please note that I receive no institutional funding for this website, nor have I received any for my work on the We Stand With Shaker campaign, the high-profile campaign, launched last November, which, I’m pleased to be able to say, played a part in securing the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, on October 30.

If you can help out at all, please click on the “Donate” button above to donate via PayPal (and I should add that you don’t need to be a PayPal member to use PayPal). You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make This Recurring (Monthly),” and if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.