Andy Worthington's Blog, page 54

May 26, 2017

Guantánamo’s Difficult Diaspora: Former Prisoner Hussein Al-Merfedy, in Slovakia, Still Feels in a Cage

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Over the last few months, I’ve been catching up on some stories I missed, about former Guantánamo prisoners seeking — and often struggling — to adjust to life in third countries, which took them in when the US government refused or was unable to repatriate them after they had been approved for release by high-level US government review processes.

Since 2006, dozens of countries have offered new homes to Guantánamo prisoners, and the examples I have looked at have mostly focused on men resettled in various European countries — see Life After Guantánamo: Yemeni Released in Serbia Struggles to Cope with Loneliness and Harassment (about Mansoor al-Dayfi, released in July 2016), Life After Guantánamo: Egyptian in Bosnia, Stranded in Legal Limbo, Seeks Clarification of His Rights (about Tariq al-Sawah, released in January 2016), and Life After Guantánamo: Yemeni Freed in Estonia Says, “Part of Me is Still at Guantánamo” (about Ahmed Abdul Qader, released in January 2015). In The Anguish of Hedi Hammami, A Tunisian Released from Guantánamo in 2010, But Persecuted in His Homeland, I also wrote about the difficulties faced by Hammami, a Tunisian first released in Georgia, who returned to his home country after the Arab Spring, only to find that he faces “a constant regimen of police surveillance.”

One day, I hope, all the men released from Guantánamo will have lawyers successfully negotiate an acceptable basis for their existence with the US government. As it currently stands, they are regarded as “illegal enemy combatants” or “unprivileged enemy belligerents,” even though almost all were never charged with any sort of crime, and their status, compared to every other human being on earth, remains frustratingly a unacceptable unclear. This is especially true, I believe, for those settled in third countries, as no internationally accepted rulebook exists to codify their rights, and the obligations of those taking them in.

In catching up on the stories I missed, I’m cross-posting below an article that was published in Newsweek last September, written by the intrepid photographer and journalist Alex Potter, who mostly works in Yemen. Potter met with Hussein al-Merfedy, a Yemeni resettled in Slovakia in November 2014, along with a Tunisian, Hisham Sliti, and her article also includes a video of al-Merfedy speaking, and 20 photos, not just of al-Merfedy and his life in Zvolen, in Slovakia, but also of Salah al-Dhaby (known in Guantánamo as Saleh al-Zabe, or Salah al-Thabi), a Yemeni resettled in Tbilisi, Georgia at the same time as al-Merfedy (seen for the first time in Potter’s photos, as no photo of him at Guantánamo was ever released), and Sabry al-Quraishi (aka Sabri al-Qurashi), resettled in Semey, Kazakhstan in December 2014, who, as Potter describes it, “lives a lonely life in Semey.” He told her, “I miss my family — I was in prison for over a decade, and I am still not able to bring my family here to visit me.” When she met him in December 2015, he showed her “some of the artwork he created while in Guantánamo.” He “claimed to have had thousands of drawings,” but in the end they “returned to him only a small folder.”

For Hussein al-Merfedy (identified at Guantánamo as Hussein Almerfedi), as I wrote at the time of his release, his long imprisonment at Guantánamo was preceded by him being “one of dozens of the more unfortunate prisoners” to be “held in secret CIA prisons prior to his transfer to Guantánamo.” He claimed he had traveled to Pakistan as a missionary, but particularly hoped to make it to Europe, where he envisioned a more open society than Yemen. He also stated that he had paid a smuggler to get him to Greece via Iran and Turkey, but was seized in Iran, and ended up being handed over to Afghan forces, who then hand him on to the US.

In Guantánamo. he explained that he was held for a total of 14 months in three prisons in Afghanistan — “two under Afghan control and one under US control,” although he added that they all “seemed to be under US supervision.” One of these prisons was Bagram, and another was the “Dark Prison” near Kabul. Almerfedi stated that he was only interrogated on three occasions in Afghanistan, and that on each occasion he was told that the authorities knew he was innocent and would soon be released.

Potter runs briefly though the story of how he ended up at Guantánamo, but her portrait is more concerned with the contours of his life post-release, and the difficulties of adjusting to life in “the only EU member state without a real mosque, ‘ where, in response to the colossal refugee crisis, from Syria and elsewhere, prime minister, Robert Fico, told a Slovak news agency that “Islam has no place in Slovakia.”

For al-Merfedy, however, as for the other men Potter spoke to, the abiding impression is one of a dreadful loneliness. “We thought we would be free when we left Guantánamo,” he told her, adding, “Instead, we went from the small Guantánamo to here — a bigger Guantánamo.” As she also explained, he has “a large family back in Yemen and would like to see them again,” but he “is a permanent resident alien, not a refugee or an asylum seeker, so Slovakia is not legally obligated to reunite him with his mother, sisters or brothers.”

Life After Guantánamo: Former Detainees Live in Limbo

By Alex Potter, Newsweek, September 1, 2016

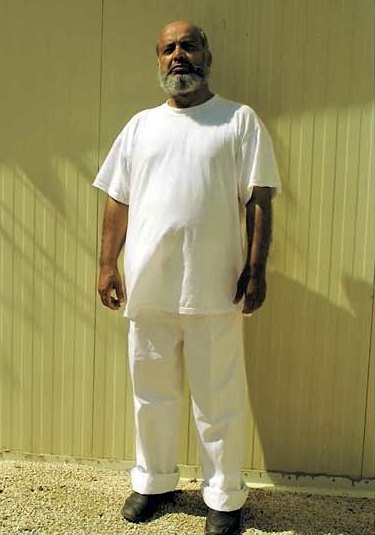

It’s early Sunday morning, and the streets of Zvolen are empty. Most in this midsize town in Slovakia are attending church, while others battle hangovers from the previous night. Hussein al-Merfedy has a bad headache too, but it’s a migraine, not something alcohol-related. He’s a Muslim and former detainee at the U.S. prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

Two years ago, al-Merfedy was one of dozens of detainees the U.S. kept locked up at Gitmo, even though they were never charged with a crime. Though he had been cleared for release in 2008, he spent more than a decade in prison without explanation. That changed on November 14, 2014, when the military handcuffed and blindfolded al-Merfedy and put him on a plane. When he landed, however, he was not home in Yemen; he was thousands of miles away in Slovakia, a stranger in a new country.

Al-Merfedy pulls himself out of bed and trudges toward the bathroom, his baggy beige pajama pants hanging low on his hips. He received these pants at Gitmo and still wears them around the house. It’s a habit, he says, that’s hard to change. Standing in front of the mirror, he runs his hands through his hair; until a month ago, it fell past his shoulders. Now it’s cropped short, “so I could fit in. So people don’t stare at me so much.”

Soon al-Merfedy makes his way to the kitchen. It looks almost new: a few dishes are stacked neatly in the drying rack, the countertops are spotless, and the fridge is nearly empty. The apartment is silent, save for the ticking of a clock and the chirping of his pet finch, which sits in a cage. Al-Merfedy has few visitors. His only friends are his caseworkers and a handful of Gitmo detainees who live elsewhere in town. Today will be just like any other for him. There is nothing to do, no one to see.

“I am almost 40 years old,” he says. “I imagined having a family and children one day. But here I am, still alone.”

‘Islam Has No Place in Slovakia’

Over the past two years, the Obama administration has renewed its push to close Gitmo and release detainees it no longer deems a threat. Of the roughly 780 original prisoners, 61 remain behind bars, 20 of whom are cleared for release. But detainees from war-torn countries like Yemen, Libya and Syria cannot return home; the U.S. government fears they might join or rejoin extremist groups.

Instead, the Defense Department has released 55 former detainees to Gulf states rather than their home nations. But these countries will take only so many men, so others were forced to go to Kazakhstan and Slovakia, where they’ve struggled to adjust. “The idea seemed to be to get them out of Guantánamo at almost any cost,” says David Remes, a lawyer to many present and former detainees, including al-Merfedy. “They were dropped into strange lands, with cultures, religions and language far different from their own, and where they were bound to be treated like pariahs.”

Adapting to life in Slovakia has been difficult for al-Merfedy. In his new town, aside from four other former Guantánamo detainees, the only other Muslim he knows is a Turkish man who owns a kebab shop. He sometimes goes to Martin, a city about two hours away where a small group of Muslims hold Friday prayers in the back of a coffee shop. (Slovakia is the only EU member state without a real mosque.) “The people here are maskeen,” al-Merfedy says, using the Yemeni word for “kind” or “good-hearted.” “The problem is with the government.”

The refugee crisis that began in 2015 brought hundreds of thousands of Muslims from the Middle East to Europe. That brought a backlash over fears the newcomers will compete for jobs and resort to terrorism. “Islam,” the country’s prime minister, Robert Fico, recently told a Slovak news agency, “has no place in Slovakia.”

Men like al-Merfedy are seemingly stuck in limbo, neither behind bars nor completely free. They are not banned from working, but no one will hire them; they want to marry, but Muslim women are scarce; they long to reunite with their families, but more than a year after release, they are still alone. “Each day, I walk through Tbilisi,” says Salah al-Dhaby, a Yemeni former detainee who was transferred to Georgia. “I live a silent life, wandering the streets, then going back to a silent apartment.”

Men like al-Merfedy are seemingly stuck in limbo, neither behind bars nor completely free. They are not banned from working, but no one will hire them; they want to marry, but Muslim women are scarce; they long to reunite with their families, but more than a year after release, they are still alone. “Each day, I walk through Tbilisi,” says Salah al-Dhaby, a Yemeni former detainee who was transferred to Georgia. “I live a silent life, wandering the streets, then going back to a silent apartment.”

That silence, al-Merfedy says, feels like a cage. “We thought we would be free when we left Guantánamo,” he says. “Instead, we went from the small Guantánamo to here — a bigger Guantánamo.”

Sold to the Afghans

Al-Merfedy’s troubles began when he traveled from Yemen to Pakistan to look for work in 2001. After connecting with an Islamic missionary organization, he decided to travel to Europe to find work. Yet in the wake of 9/11, visas for Yemenis, even those registered with legitimate organizations, were difficult to obtain. Al-Merfedy was undeterred. He paid someone to smuggle him across Pakistan and Afghanistan, through Iran and into Turkey, where he hoped to find a way to Europe. He was captured in Iran, accused of being an Al-Qaeda recruiter and sold to Afghan authorities. The Afghans sent him to the Americans, who then transferred him to Guantánamo on May 9, 2003. His missionary group, the U.S. believes, was often used a front for extremists.

For five years, al-Merfedy remained behind bars, maintaining his innocence. His attorney points out that local groups often exploited lucrative American bounties for those connected to Al-Qaeda and sometimes delivered innocent men. Others seemed to be marginal players in the war on terror. “Few ‘combatants’ are even accused of having fought,” according to a 2006 report by Human Rights Watch. “Many are held simply because they were living in a house associated with the Taliban or working for a charity linked to the group.”

Whether al-Merfedy is innocent remains unclear; the Defense Department and the State Department’s Special Envoy for Guantánamo Closure do not discuss the details of individual cases. But the U.S. cleared him for release in 2008, no longer deeming him a threat. After American intelligence officials discovered that Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab (the “Underwear Bomber”) was trained in Yemen, however, the U.S. refused to transfer al-Merfedy or any of his countrymen back there. “The decision to transfer a detainee is made only after detailed, specific conversations with the receiving country about the potential threat a detainee may pose after transfer and the measures the receiving country will take in order to sufficiently mitigate that threat, and to ensure humane treatment,” says Lt. Col Valerie Henderson, a Defense Department spokesperson.

Some six years later, after more than a decade of intermittent “enhanced interrogations,” hunger strikes and solitary confinement, he was called into an office at Gitmo. There he met liaisons from Slovakia, who promised him a new life, and al-Merfedy was excited. “I wanted to leave Guantánamo,” he says.

Now that he is free, al-Merfedy is part of a two-year program run by the International Organization for Migration to make him feel more comfortable. This includes paid housing and a monthly stipend, Slovak language teachers, a psychologist and a social worker. Yet, so far, al-Merfedy has struggled to find a job and is worried what will happen next year, when the IOM cuts his stipend in half. The group says it would consider an extension, but only if it can prove to the government he is learning Slovak. Al-Merfedy says he is trying, but his classes are in English, a language he doesn’t speak well, which makes the learning process slow. He knows the basic greetings: dobry den (good morning), prosim (please) and dakujem (thank you). He can pass for a tourist, but nothing more.

Who’d Marry an Ex-Gitmo Man?

Around lunchtime, al-Merfedy strolls into town, gazing at the ground, occasionally looking up and smiling as he sees young couples holding hands or fathers playing with their children. Some pass him with a slight smile. Others eye him with suspicion or curiosity.

The 39-year-old had a large family back in Yemen and would like to see them again. But al-Merfedy is a permanent resident alien, not a refugee or an asylum seeker, so Slovakia is not legally obligated to reunite him with his mother, sisters or brothers. He wants to raise a family, but in a country with few Muslims and fewer who would marry a former Gitmo detainee, his prospects are bleak. According to Pooja Jhunjhunwala, a spokesperson for the State Department, “We support family reunification because we believe it leads to successful outcomes, successful integration.” However, the receiving countries actions do not always match State Department views.

Hussein is still waiting for the government to approve a visa allowing his family to visit. “Maybe if I was with my family, it would be OK,” he says, “but … I am a stranger. I am in exile. I have been longing for things my whole life, but they have all been decided for me.”

Later that day, as the sunlight fades, so too does Hussein’s headache, and by the time fog descends onto the streets, he feels better. He walks the solitary mile to his apartment, taking backstreets to avoid revelers spilling out of local bars. When he arrives, the sun is setting over Zvolen, and al-Merfedy pulls down his shades.

Once again, his apartment is silent, save for the ticking of the clock and the sound of the finch singing its evening song. “I hate to see anything in a cage,” he says as he fills the bird’s water and food containers. “I was in a cage my whole life.”

He pulls out a thin blanket and places it gently over the cage. After a moment, the bird goes silent.

This piece was produced with the support of the IWMF Howard G. Buffet Fund for Women Journalists.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 24, 2017

DIY Cultures 2017: The Counter-Culture Is Alive and Well at a Zine Fair in Shoreditch

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Last week I paid a visit to DIY Cultures, a wonderful — and wonderfully packed — one-day event celebrating zines and the DIY ethos at Rich Mix in Shoreditch, curated by a core collective of Sofia Niazi, my friend Hamja Ahsan and Helena Wee, and was pleasantly reminded of the presence of the counter-culture, perhaps best summed up as an oppositional force to the prevailing culture, which has long fascinated me, and in search of which I am currently bouncing around ideas for a writing project I’d like to undertake.

Next week it will be exactly ten years since I started publishing articles here — on an almost daily basis — relating, for the most part, to Guantánamo and related issues. Roll back another year, to March 2006, and my Guantánamo project began in earnest, with 14 months of research and writing for my book The Guantánamo Files.

Before that, however, I had been interested more in notions of the counter-culture than championing and trying to reinforce the notion that there are absolute lines that societies that claim to respect the law must not cross — involving torture and imprisoning people indefinitely without charge or trial.

Before Guantánamo took over my life, I had spent the previous ten years looking at ancient sacred sites of the neolithic and Bronze Age, and, particularly, Stonehenge and Avebury in Wiltshire, making countless visits to these two sites and to numerous others — not just across the length and breadth of the UK, but also in Malta and Brittany. After years spent trying to write a book about my experiences — particularly focused on three long-distance walks I undertook with friends in 1997 and 1998 — it was suggested to me that a book looking specifically at the Stonehenge Free Festival, which I had visited in 1983 and 1984, and had included in my writing, might make a publishable book, and so I embarked on the life-changing process of researching and writing what became my first published book, Stonehenge: Celebration & Subversion, in June 2004. See my archive of subsequent articles about Stonehenge here.

Interweaving the archaeologists’ story of Stonehenge with that of the various outsiders drawn to the monument over the years, the book was, at some fundamental level, a counter-cultural history of post-war Britain — something that had always interested me. Growing up, my cultural reference points were the 1960s, and I was drawn to the hippie movement — the music, the fashion, and the hippies’ anti-establishment position — even as homegrown dissidents, the punks, were railing against the legacy of the 1960s.

What interested me — and the punks were no different, fundamentally — was the energy of a life established in defiance of the status quo, and this was clearly something that had happened in the 60s, when the existing culture was challenged in terms of music, fashion and politics, and a distinctive counter-culture developed, with the creation of underground magazines and newspapers, free festivals, free food kitchens, squatting, cooperatives and communes.

By the mid-70s, the punks responded to what they saw as the bloated failure of the 60s, but they were only partly right, and they were only partly in revolt. The punk movement also brought its own DIY ethos, and a whole raft of fanzines too and other graphic output, like the poster reproduced here, from a series that was on display at Rich Mix, made by Rock Against Racism in Hull in the late 70s, when I lived there. I actually saw some of the gigs, and was also a founder member of Human Zoo, one of the bands featured on this poster.

By the mid-70s, the punks responded to what they saw as the bloated failure of the 60s, but they were only partly right, and they were only partly in revolt. The punk movement also brought its own DIY ethos, and a whole raft of fanzines too and other graphic output, like the poster reproduced here, from a series that was on display at Rich Mix, made by Rock Against Racism in Hull in the late 70s, when I lived there. I actually saw some of the gigs, and was also a founder member of Human Zoo, one of the bands featured on this poster.

What had happened in the early 70s, I later realised, was that the hippies’ two main impulses — the political desire for change, and the more metaphysical desire for self-knowledge — had become separated, and while the influence of the former dwindled, after manifesting itself in some genuinely revolutionary movements in the late 60s and early 70s, the latter became the all-consuming monster that it is today — the quest for self-knowledge having turned into the most cynical and all-encompassing cult of the individual, in which everyone’s individual desires are regarded as “needs” and we are all encouraged to believe that we are entitled to whatever we want — or whatever cynical marketing types try to convince us we want, because, as the saying goes, “we’re worth it.”

In the 80s, under Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, the establishment pushed back in a concerted and often violent manner against the counter-culture — see, for example, The Battle of the Beanfield in the UK, when Thatcher used the police as a paramilitary force against the travellers, anarchists and environmental activists planning to set up the 12th annual Stonehenge Free Festival. Despite this and other assaults on the counter-culture, however, Thatcher’s obsession with stifling dissent and creating a population of pliant homeowners was only partly successful.

Acid house and the road protest movement — both emerging completely unexpectedly in the late 80s and early 90s — revealed the counter-culture to be both surprisingly adaptable and, at the time, fundamentally uncrushable, and the pre-Blair 90s, in hindsight, following on from 1990’s Poll Tax Riot and Thatcher’s resignation, were memorable as the time when the Tories’ control of society, under John Major, was close to tenuous. For millions of people, myself included, mutiny was an almost permanent facet of life.

Then came Tony Blair, and what I describe as the psychic cosh with which he pummelled the British counter-culture into submission. “Unless you’re rich, go to bed early and don’t make too much noise”, Blair seemed to say, as he led the second wave of Thatcherism, the exultation of greed above all else, the commodification of everything, the dull primacy of money above the endless fascinations of a life where money is explicitly NOT the defining motivation of existence.

Since then, the counter-culture has struggled to survive, as the mainstream corporate world now eats up everything that shows the faintest signs of challenging late capitalism’s control freak omni-presence. Added to this, the rapid evolution of technology — in particular via the so-called smartphone — has ushered in a new, and as yet incompletely understood era of mass communication and interconnectivity, whose positives, it seems, threaten to be outweighed by its negatives.

Although, on the one hand, we can make friends around the world and the internet has created the opportunity for an extraordinary abundance of DIY publishing and all manner of creation online, there are profound problems too: far too much money is concentrated in a handful of tech companies, while creators are squeezed, and, of course, there are the problems of search engines and their dodgy algorithms, and echo chambers dumbing down politics and creating ghettoes of the like-minded, as well as the existence of cyber-bullies, individuals who spread hatred and encourage violence while hiding behind convenient pseudonyms.

In a world where everything is online and ephemeral, the counter-culture, it seems, is partly reasserting itself by taking back the means of manufacture and creating artefacts. That’s partly visible in the resurgence of vinyl, although, cynically, the major corporate labels have tried to take that over, and it’s also visible in the return of the audio cassette, a few of which were available at DIY Cultures. Primarily, however, there was an ocean of zines, posters and postcards, printed using real printing presses, or photocopied — some dealing very explicitly with politics (left-wing, anarchist and sexual, for example), while others dealt with the more whimsical and fantastical, but all of it, it seemed to me, was reasserting the counter-cultural necessity of reclaiming our creativity, and expressing it in forms and venues that are outside of corporate control.

And to add to this printed output, the day also featured several panel discussions, with themes including how to deal with Theresa May, how to deal with Brexit, and guests including the Artist Taxi Driver, who is raising funds for a “Brexshit” film, and Saffiyah Khan, the activist who recently stood up to the EDL in Birmingham.

Next year I hope to find a way to take part, but in the meantime I hope to find the time to further develop my project to analyse and curate a history of the counter-culture from the 60s to now. Any suggestions or leads will be very gratefully received.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 22, 2017

Witness Against Torture Launch “Forever Human Beings,” a 41-Day Campaign for the 41 “Forever Prisoners” Still Held at Guantánamo

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Since Donald Trump became president just over four months ago, the aggressive, and often unconstitutional incompetence emanating from the White House every day, on so many fronts, has unfortunately meant that long-standing injustices like the prison at Guantánamo Bay are in danger of disappearing off the radar completely, even more comprehensively than during the particular lulls in the presidency of Barack Obama, who largely sat on his hands between 2011 and 2013, when confronted by cynical obstruction in Congress to his hopes of closing the prison, doing very little until the prisoners forced his hand, embarking on a prison-wide hunger strike that drew the world’s attention, and embarrassed him into renewed action.

Through the Close Guantánamo campaign that I established with the attorney Tom Wilner in 2012 I have tried to keep Trump’s responsibility for Guantánamo in the public eye. Since this inauguration, opponents of Guantánamo have been sending in photos of themselves holding posters calling for Trump to close Guantánamo, which I’ve been posting on the website, and on social media — particularly through Facebook — ever since. Over 40 photos have now been published, with many more to come. Please join us. This Wednesday marks 125 days of Trump’s presidency, a suitable occasion to remind him that Guantánamo must be closed.

I’m pleased also to endorse a new initiative by Witness Against Torture, the campaigning group whose work is very close to my heart. Every January, on my annual visits to call for the closure of Guantánamo on an around the anniversary of its opening (on January 11), I spend time with members of Witness, many of whom have, over the years, become my friends, and I was delighted, a few days ago, to receive an email notifying me about “Forever Human Beings,” a 41-Day Campaign for the 41 “Forever Prisoners” Still Held at Guantánamo, launching this Friday, May 26.

Below is their article announcing the new initiative, with many planned actions listed, including, in the first instance, a rolling fast in which you are invited to take part. To contact them please also follow them on Facebook and Twitter.

#foreverhumanbeings: A Campaign to Close Guantánamo

“Are we going to pretend they’re less than men and walk away?”

– Luke Nephew (Peace Poet), “There is a Man Under the Hood”

Forty-one human beings remain incarcerated in the prison at Guantánamo. All potentially face lifetimes of detention. Five have been cleared for release by the US government itself. But they were still in Guantánamo when Trump took office, and Trump has halted all transfers from the prison.

Many more are “forever prisoners,” who have not been charged with crimes, and never will be. A small handful of men are facing charges in the illegitimate and unworkable Military Commissions. If convicted, they could receive lengthy sentences, likely served at Guantánamo, or even the death penalty.

Guantánamo has always been a place of torture and the violation of human rights. It must close, no matter who is president. President Obama failed in his pledge to shutter the prison. Trump has threatened to bring new captives there. The thought of Trump — whose reckless disregard for the US Constitution is every day revealed — having Guantánamo as his private, offshore gulag is terrifying. Any day, we could learn that the Trump administration has sent a new captive to Guantánamo.

The continued existence of Guantánamo also feeds a resurgent Islamophobia and politics of fear and hate, typified by Trump’s unconstitutional “Muslim travel ban.” Guantánamo never housed simply the “worst of the worst” terrorists, as the Bush administration claimed. The vast majority of men held there never engaged in hostilities against the United States. By staying open, Guantánamo reinforces the terrible lie that all Muslims are dangerous, to be feared or even cut out of American life. To work to close Guantánamo is to support tolerance, pluralism, and respect for the rule of law.

Witness Against Torture is launching on Friday May 26: #foreverhumanbeings – A Campaign to Close Guantánamo. For a period of 41 days, spanning the holy month of Ramadan and beyond, the campaign will bring awareness to the fate of each of the 41 men detained in Guantanamo Bay Prison, coordinate public action aimed at closing Guantánamo, and draw links between Guantánamo, institutionalized Islamophobia, all forms of racism, and abuses in the US criminal justice and prison systems.

The Witness Against Torture campaign will include:

– an international and interfaith “rolling fast” throughout the campaign’s 41 days. Fasters are encouraged to incorporate concern for the abuse of men in Guantánamo during their day. If you are observing Ramadan, you may leave an empty seat at the dinner table in remembrance of the men who are in Guantánamo rather than at home with their families, during Iftar. Sign up for the Rolling Fast here. More details to come.

– phone calls, emails, and letters to relevant governmental and military offices.

– creative direct action and vigils in Washington, D.C. and other places.

– scheduled blogposts on such topics as Islamophobia, the current situation at Guantánamo, religious objections to torture, and the use of Communication Management Units in “war on terror” detentions.

– daily profiles on social media of each of the 41 detained men.

– participation on June 23 in the all-day vigil at the White House organized by the Torture Abolition and Survivors Support Coalition.

– the creation and distribution of art addressing Guantánamo, torture, and the US prisons.

Please join us in remembering the men locked away, now forever, at Guantánamo and working to close the prison!

Please also check out the video below, How to Close Guantánamo Under Trump, by Justin Norman, who does all Witness Against Torture’s photos and videos, and also designed the We Stand With Shaker website and the Gitmo Clock for Close Guantánamo.

Witness Against Torture formed in 2005 when 25 Americans went to Guantánamo Bay and attempted to visit the detention facility. They began to organize more broadly to shut down Guantánamo, end indefinite detention and torture and call out Islamophobia. During our demonstrations, we lift up the words of the detainees themselves, bringing them to public spaces they are not permitted to access. Witness Against Torture will carry on in its activities until torture is decisively ended, its victims are fully acknowledged,Guantánamo and similar facilities are closed, and those who ordered and committed torture are held to account.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 21, 2017

Video: “Zone of Non-Being: Guantánamo,” Featuring Andy Worthington, Omar Deghayes, Clive Stafford Smith, Michael Ratner

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Several years ago (actually, way back in December 2012), I was interviewed at my home for a documentary produced by the Islamic Human Rights Commission, which was directed by the filmmaker Turab Shah. For some reason, I never heard about the film being completed (I think its initial screening was in January 2014, when I was in the US), but after Donald Trump became president of the United States, I received an email from the IHRC stating that they were screening the film, which prompted me to look it up, and to discover that it had been put online in July 2014.

The film features a fascinating array of contributors, including myself, former prisoners including Omar Deghayes, Moazzam Begg and Martin Mubanga, Clive Stafford Smith, the founder of Reprieve, the late Michael Ratner, the founder of the Center for Constitutional Rights, the author and academic Arun Kundnani, Ramon Grosfoguel, Associate Professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, the journalist Victoria Brittain, the writer Amrit Wilson, and Massoud Shadjareh of the ICRC.

The ICRC described the film as follows:

‘Zone of Non-Being: Guantánamo’ looks at how the process of Guantanamisation has taken place over the last decade in the USA, and through US and allied foreign policy from the introduction of the NDAA to the use of drones. It argues that rather than being the exceptional event of the so-called War on Terror, Guantánamo is a continuation of a colonial policy that runs from 1492 and the conquest of the Americas and the destruction of Granada.

Guantánamo symbolises in a public and brutal fashion the creation of Fanon’s Zone of Non-Being – “an extraordinarily sterile and arid region, an utterly naked declivity” where violence reigns and those deemed non-beings are trapped by the on-going colonial process.

The film is posted below via YouTube, and I hope you have time to watch it and to share it if you find it useful. It’s also on Vimeo here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 19, 2017

Abu Zubaydah Will Not Testify at Guantánamo Military Court Because the US Government Has “Stacked the Deck” Against Him

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Yesterday, for Close Guantánamo, the campaign I co-founded in January 2012 with the attorney Tom Wilner, I published an article, Abu Zubaydah Waives Immunity to Testify About His Torture in a Military Commission Trial at Guantánamo, explaining how Zubydah (aka Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn), a Saudi-born Palestinian, an alleged “high value detainee,” and the unfortunate first victim of the Bush administration’s post-9/11 torture program, was planning to appear as a witness today a pre-trial hearing at Guantánamo involving Ramzi bin al-Shibh, one of five men accused of involvement in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Zubaydah was planning to discuss bin al-Shibh’s claims that “somebody is intentionally harassing him with noises and vibrations to disrupt his sleep,” as Carol Rosenberg described it for the Miami Herald, but as Mark Denbeaux, one of his lawyers, explained, by taking the stand his intention was for the truth to emerge, and for the world “to know that he has committed no crimes and the United States has no basis to fear him and no justification to hold him for 15 years, much to less subject him to the torture that the world has so roundly condemned.”

Denbeaux also explained how “the Prosecution here in the Military Commissions is afraid to try him or even charge him with any crime,” adding, “The failure to charge him, after 15 years of torture and detention, speaks eloquently. To charge him would be to reveal the truth about the creation of America’s torture program.”

Denbeaux also noted that for Abu Zubaydah testifying would be a way “to celebrate his survival and to let the world hear his voice and to see him.”

However, late yesterday evening, after nearly three hours of meetings with Zubaydah, it was revealed that he would not be testifying after all. One of bin al-Shibh’s legal team, Jim Harrington, said, “On the advice of his attorneys he has made a decision that he will not testify because the risks to him in the future from cross examination prohibit him from being able to give important testimony on the issue before the court.”

In the Miami Herald, Carol Rosenberg explained that Zubaydah “made the decision in tandem with his lawyers after his attorney Mark Denbeaux arrived at this remote Navy base Thursday afternoon.” She stated, “At issue was material Sept. 11 trial prosecutors planned to use in court to demonstrate Zubaydah’s bias against the United States, including a video showing the Palestinian before his capture in Pakistan in March 2002 praising the Sept. 11 attacks.”

This would be an unacceptable example of the US government trying to blacken Zubaydah’s name, despite having no case against him. As Rosenberg explained, although Zubaydah has admitted to having been a jihadist, “he has insisted, and US intelligence analysts have concluded, that he was not a sworn member of al-Qaida and there is no evidence he knew about the 9/11 attacks in advance.”

Speaking of what Zubaydah was supposed to be discussing, Harrington said Zubaydah had “heard the noises but [had] not felt the vibration,” but he added that the issue at stake was that prosecutor Ed Ryan intended to undertake “a sweeping cross-examination” of Zubaydah, even though the judge, Army Col. James L. Pohl, had specifically cautioned Ryan against “turning the testimony into ‘a United States versus Zubaydah case.’”

Harrington’s co-counsel, reserve Army Maj. Alaina Wichner, said, “We’re very disappointed that he’s not going to testify. But we understand the circumstance. The only people who can obviously testify for Ramzi are people who are in the camps with us, and this was an important witness for us.” She added that her team “was considering whether to call other witnesses who might validate Bin al Shibh’s claim of the disruptions.”

While this is a disappointment for bin al-Shibh, it is also a major blow for Abu Zubaydah, and his efforts to hold the US government to account of this torture, and for their failure to charge him or release him. Mark Denbeaux issued a statement to the press, which I’m cross-posting below in its entirety, as it perfectly captures the disgraceful position taken by the government. As Denbeaux describes it, they have “stacked the deck” against Zubaydah, because “the court gave virtual free reign to the prosecution in search of proving bias — while extremely limiting my client’s ability to respond meaningfully about his experience.”

Statement to the Press

By Mark P. Denbeaux

On May 19, 2017 counsel for the detainee known as Abu Zubaydah chose to not allow their client to testify.

We could not allow our client to testify; the Government stacked the deck. We stipulated to bias against the US. but the court gave virtual free reign to the prosecution in search of proving bias — while extremely limiting my client’s ability to respond meaningfully about his experience.

Faced with overwhelming evidence that they tortured the wrong man, the Government wanted to cherrypick statements to paint a picture of prejudice under this cloak of “bias” without telling the whole story.

We invaded this man’s country, waterboarded him 83 times and tortured him for 4 years in secret prisons where he lost an eye. Of course he’s biased. He’s been imprisoned for 15 years without being charged and while he was being tortured, the CIA officially directed that he be silenced as long as he lived, forever and without fail. And if that wasn’t enough, they ordered his body cremated — assuring his silence even beyond the grave.

Tell me, what kind of people burn the bodies of their victims? Not innocent ones. And not people who want their victims to talk. These proceedings ultimately turned out to be just a continuation of that campaign of silence. We, perhaps foolishly, had hoped for better.

Before being captured, my client made a video extremely critical of the United States. My client fought against the Soviets and their agents as a mujahadeen, and then vowed to fight again against anyone who invaded his country, and to stand in solidarity with anyone who defended it. It was a response to battle. He essentially made a pledge of allegiance to his country and his beliefs. How is that a crime in America? Millions of American soldiers and schoolchildren take oaths and make a pledge of allegiance every day — does that mean they’re all guilty of the horrific torture that the CIA performed against my client? Expressing allegiance to one’s beliefs is not a crime in America. Maybe that’s why the prosecution in Guantánamo refuses to charge him.

The Government sought not truth, but stacked the deck in a way that made it impossible for my client to be presented fairly and accurately. For those reasons, we have respectfully abstained from taking part in this dog and pony show.

Mark P. Denbeaux

Lead Civilian Military Defense Counsel for Zayn Abu Zubaydah

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 16, 2017

Ismail Einashe, British Citizen of Somali Origin, Describes How The Status of Migrants is “Permanently Up for Review” in the New Intolerant UK

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

What strange, and almost unbelievably infuriating times we live in, as Donald Trump somehow remains president in the US, and Britain continues to be bludgeoned by a phoney demonstration of democracy. The latest example is the General Election on June 8, which follows a previous example just two years ago, despite the Tories introducing legislation to ensure that elections only take place every five years. In between, there was, of course, the lamentable EU referendum that is the reason for this General Election, as Theresa May struggles to provide endless distractions from the reality that leaving the EU will be an unmitigated disaster, the single greatest instance of a nation declaring economic suicide in most, if not all of our lifetimes.

For Theresa May, this is an election in which nothing must be discussed, just the endless repetition of soundbites about being “strong and stable,” and lies about how an increased Tory majority will improve our Brexit negotiations. In fact, the size of the government’s majority means nothing at all in the negotiations with the EU that the Tories want to avoid discussing because they have no idea what they are doing, and while this is ostensibly good for the opposition parties, the Brexit blanket, like a thick fog, is tending to obscure any serious discussion of the government’s many other failings — on the economy, on the NHS, on all manner of fronts — and this, of course, is being aided by the generally biased, right-wing media that is such a drag on anything resembling progressive politics in this country

What is also being forgotten, or overlooked, is how Theresa May, a soft Remainer who has, cynically, turned herself into the hardest of hard Brexiteers, is so dangerous not only because her actions reveal how she has no principles whatsoever that she will not sacrifice to stay in power, but also because, in her previous job, as the home secretary, she was dangerously racist, xenophobic and Islamophobic. I discussed her record in detail at the time of her leadership victory, in an article entitled, As Theresa May Becomes Prime Minister, A Look Back at Her Authoritarianism, Islamophobia and Harshness on Immigration, and I was reminded of it a few months ago in a detailed article by the journalist Ismail Einashe, a British citizen of Somali origin, which he wrote for the spring 2017 edition of the New Humanist magazine, and which was then picked up by the Guardian.

I’ve been meaning to cross-post it ever since, and am taking the opportunity to do so now because racism, xenophobia and Islamophobia are actually at the heart of Britain’s current suicidal woes — and are also a key part of the worldview of our wretched Prime Minister.

Einashe, who arrived in the UK from Somalia in 1994 and got a British passport in 2002, points out how, over the last 15 years, the key concept of citizenship has been eroded, and he reminds those who had forgotten — or perhaps never even knew in the first place — how central a role Theresa May has played in this.

He traces the problem with the perception of Muslims in the UK back to two events in 2001 — 9/11, of course, but also the race riots in the north of England, which, he notes, “provoked a fraught public conversation on Muslims’ perceived lack of integration, and how we could live together in a multi-ethnic society.” Interestingly, one of the first public events I took part in as a speaker on Guantánamo, in 2007, was with Arun Kundnani, who had written an excellent book, The End of Tolerance: Racism in 21st Century Britain, which included analysis of the riots, demonstrating that it was unemployment that had led to friction between different cultures. In the past, different cultures met on the factory floor, but with no work in neo-liberal Britain, Muslims in the northern towns where the riots took place had ended up accidentally ghettoised, although the white British saw that as deliberate isolation.

As the hysteria mounted, Einashe notes, “the Blair government decided to use a little-known law – the 1914 British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act – to revoke the citizenship of naturalised British persons, largely in terrorism cases.”

Of key concern are the following two paragraphs, making reference to the stripping of citizenship under Theresa May that I discussed in 2014 in two articles, The UK’s Unacceptable Obsession with Stripping British Citizens of Their UK Nationality and MPs Support Alarming Citizenship-Stripping Measures Introduced by Theresa May. As Einashe states:

In 2006, the home secretary was given further powers to revoke British citizenship. At the time, the government sought to allay concerns about misuse of these powers. “The secretary of state cannot make an order on a whim,” the home office minister Angela Eagle had said when the law was first proposed, “and he[/she] will be subject to judicial oversight when he[/she] makes an order.”

Although the post-9/11 measures were initially presented as temporary, they have become permanent. And the home secretary can strip people of their citizenship without giving a clear reason. No court approval is required, and the person concerned does not need to have committed a crime. The practice is growing. Under Labour, just five people had their citizenship removed, but when Theresa May was at the Home Office, 70 people were stripped of their citizenship, according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Yet these near-arbitrary powers have caused remarkably little concern.

In his conclusion, Einashe writes that, in the UK today, “becoming a naturalised citizen is no longer a guarantee against the political whims of the day: you are, in effect, a second-class citizen.” He adds that “[c]itizenship-stripping is now a fixture of the state,” and correctly describes it as an unacceptable move by the government to “empower” itself “at the expense of ordinary people.” He cites Hannah Arendt, the political theorist, who “memorably described citizenship as ‘the right to have rights,’” but adds that “for people of migrant background such as myself, this is being eroded. We are not a small group: according to the 2011 census, there are 3.4 million naturalised Brits.”

With Trump in power in the US, having attempted to implement a ban on Muslims from seven countries, Einashe notes that he “happened to be visiting New York at the time,” and the ban “left me wondering if I will ever be allowed to again.” With the virus of intolerance spreading so easily form country to country, Trump’s ban — though subject to massive legal challenges in the US — has nevertheless resonated with those seeking to defend intolerance in other countries, and not for nothing does Einashe end his article by stating that, “In other liberal democracies such as Australia and Canada, moves are under way to enable citizenship-stripping – sending people like me a clear message that our citizenship is permanently up for review.”

I hope you have time to read there article, and that you will share it if you find it useful.

The struggle to be British: my life as a second-class citizen

By Ismail Einashe, the Guardian, March 2, 2017

After arriving in Britain as a child, I fought hard to feel like I belonged. Now it feels that the status of migrants like me is permanently up for review.

I used my British passport for the first time on a January morning in 2002, to board a Eurostar train to Paris. I was taking a paper on the French Revolution for my history A-level and was on a trip to explore the key sites of the period, including a visit to Louis XIV’s chateau at Versailles. When I arrived at Gare du Nord I felt a tingle of nerves cascade through my body: I had become a naturalised British citizen only the year before. As I got closer to border control my palms became sweaty, clutching my new passport. A voice inside told me the severe-looking French officers would not accept that I really was British and would not allow me to enter France. To my great surprise, they did.

Back then, becoming a British citizen was a dull bureaucratic procedure. When my family arrived as refugees from Somalia’s civil war, a few days after Christmas 1994, we were processed at the airport, and then largely forgotten. A few years after I got my passport all that changed. From 2004, adults who applied for British citizenship were required to attend a ceremony; to take an oath of allegiance to the monarch and make a pledge to the UK.

These ceremonies, organised by local authorities in town halls up and down the country, marked a shift in how the British state viewed citizenship. Before, it was a result of how long you had stayed in Britain – now it was supposed to be earned through active participation in society. In 2002, the government had also introduced a “life in the UK” test for prospective citizens. The tests point to something important: being a citizen on paper is not the same as truly belonging. Official Britain has been happy to celebrate symbols of multiculturalism – the curry house and the Notting Hill carnival – while ignoring the divisions between communities. Nor did the state give much of a helping hand to newcomers: there was little effort made to help families like mine learn English.

But in the last 15 years, citizenship, participation and “shared values” have been given ever more emphasis. They have also been accompanied by a deepening atmosphere of suspicion around people of Muslim background, particularly those who were born overseas or hold dual nationality. This is making people like me, who have struggled to become British, feel like second-class citizens.

*****

When I arrived in Britain aged nine, I spoke no English and knew virtually nothing about this island. My family was moved into a run-down hostel on London’s Camden Road, which housed refugees – Kurds, Bosnians, Kosovans. Spending my first few months in Britain among other new arrivals was an interesting experience. Although, like my family, they were Muslim, their habits were different to ours. The Balkan refugees liked to drink vodka. After some months we had to move, this time to Colindale in north London.

Colindale was home to a large white working-class community, and our arrival was met with hostility. There were no warm welcomes from the locals, just a cold thud. None of my family spoke English, but I had soon mastered a few phrases in my new tongue: “Excuse me”, “How much is this?”, “Can I have …?”, “Thank you”. It was enough to allow us to navigate our way through the maze of shops in Grahame Park, the largest council estate in Barnet. This estate had opened in 1971, conceived as a garden city, but by the mid-1990s it had fallen into decay and isolation. This brick city became our home. As with other refugee communities before us, Britain had been generous in giving Somalis sanctuary, but was too indifferent to help us truly join in. Families like mine were plunged into unfamiliar cities, alienated and unable to make sense of our new homes. For us, there were no guidebooks on how to fit into British society or a map of how to become a citizen.

My family – the only black family on our street – stuck out like a sore thumb. Some neighbours would throw rubbish into our garden, perhaps because they disapproved of our presence. That first winter in Britain was brutal for us. We had never experienced anything like it and my lips cracked. But whenever it snowed I would run out to the street, stand in the cold, chest out and palms ready to meet the sky, and for the first time feel the sensation of snowflakes on my hands. The following summer I spent my days blasting Shaggy’s Boombastic on my cherished cassette player. But I also realised just how different I was from the children around me. Though most of them were polite, others called me names I did not understand. At the playground they would not let me join in their games – instead they would stare at me. I knew then, aged 11, that there was a distance between them and me, which even childhood curiosity could not overcome.

Although it was hard for me to fit in and make new friends, at least my English was improving. This was not the case for the rest of my family, so they held on to each other, afraid of what was outside our four walls. It was mundane growing up in working-class suburbia: we rarely left our street, except for occasional visits to the Indian cash-and-carry in Kingsbury to buy lamb, cumin and basmati rice. Sometimes one of our neighbours would swerve his van close to the pavement edge if it rained and he happened to spot my mother walking past, so he could splash her long dirac and hijab with dirty water. If he succeeded, he would lean out of the window, thumbs up, laughing hysterically. My mother’s response was always the same. She would walk back to the house, grab a towel and dry herself.

At secondary school in Edgware, the children were still mostly white, but there was a sizeable minority of Sikhs and Hindus. My new classmates would laugh at how I pronounced certain English words. I couldn’t say “congratulations” properly, the difficult part being the “gra”. I would perform saying that word, much to the amusement of my classmates. As the end of term approached, my classmates would ask where I was going on holiday. I would tell them, “Nowhere”, adding, “I don’t have a passport”.

When I was in my early teens, we were rehoused and I had to move to the south Camden Community school in Somers Town. There, a dozen languages were spoken and you could count the number of white students in my year on two hands. There was tension in the air and pupils were mostly segregated along ethnic lines – Turks, Bengalis, English, Somalis, Portuguese. Turf wars were not uncommon and fights broke out at the school gates. The British National party targeted the area in the mid-1990s, seeking to exploit the murder of a white teenager by a Bengali gang. At one point a halal butcher was firebombed.

Though I grew up minutes from the centre of Europe’s biggest city, I rarely ventured far beyond my own community. For us, there were no trips to museums, seaside excursions or cinema visits. MTV Base, the chicken shop and McDonald’s marked my teen years. I had little connection to other parts of Britain, beyond the snippets of middle-class life I observed via my white teachers. And I was still living with refugee documents, given “indefinite leave to remain” that could still be revoked at some future point. I realised then that no amount of identification with my new-found culture could make up for the reality that, without naturalisation, I was not considered British.

At 16, I took my GCSEs and got the grades to leave behind one of the worst state schools in London for one of the best: the mixed sixth form at Camden School for Girls. Most of the teens at my new school had previously attended some of Britain’s best private schools – City of London, Westminster, Highgate – and were in the majority white and middle-class.

It was strange to go from a Muslim-majority school to a sixth form where the children of London’s liberal set attended: only a mile apart, but worlds removed. I am not certain my family understood this change. My cousins thought it was weird that I did not attend the local college, but my old teachers insisted I go to the sixth form if I wanted to get into a good university. A few days after starting there, I got my naturalisation certificate, which opened the way for me to apply for my British passport.

*****

Around the time I became a British citizen, the political mood had started to shift. In the summer of 2001, Britain experienced its worst race riots in a generation. These riots, involving white and Asian communities in towns in the north-west of England, were short but violent. They provoked a fraught public conversation on Muslims’ perceived lack of integration, and how we could live together in a multi-ethnic society. This conversation was intensified by the 9/11 attacks in the US. President George W Bush’s declaration of a “war on terror” created a binary between the good and the bad immigrant, and the moderate and the radical Muslim. The London bombings of 7 July 2005 added yet more intensity to the conversation in Britain.

Politicians from across the spectrum agreed that a shared British identity was important, but they couldn’t agree on what that might be. In 2004, the Conservative leader Michael Howard had referred to “The British dream” when speaking about his Jewish immigrant roots. After 2005, he wrote in the Guardian that the tube attacks had “shattered” complacency about Britain’s record on integration. Britain had to face “the terrible truth of being the first western country to have suffered terrorist attacks perpetrated by ‘home-grown’ suicide bombers – born and educated in Britain”. Many commentators questioned whether being a Muslim and British were consistent identities; indeed whether Islam itself was compatible with liberal democracy.

Howard defined a shared identity through institutions such as democracy, monarchy, the rule of law and a national history. But others argued that making a checklist was a very un-British thing to do. Labour’s Gordon Brown, in a 2004 article for the Guardian, wrote that liberty, tolerance and fair play were the core values of Britishness. While acknowledging such values exist in other cultures and countries, he went on to say that when these values are combined together they make a “distinctive Britishness that has been manifest throughout our history and has shaped it”.

For me, at least, becoming a British citizen was a major milestone. It not only signalled that I felt increasingly British but that I now had the legal right to feel this way.

But my new identity was less secure than I realised. Only a few months after my trip to Paris, the Blair government decided to use a little-known law – the 1914 British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act – to revoke the citizenship of naturalised British persons, largely in terrorism cases. Before 1914, British citizenship, once obtained, could only be given up voluntarily by an individual, but that changed with the advent of the first world war. According to the Oxford politics professor Matthew Gibney, the 1914 act was a response to anti-German sentiment and fears about the loyalty of people with dual British-German citizenship. A further law, passed in 1918, created new and wide-ranging grounds to revoke citizenship.

In theory, since 1918, the home secretary has had the power to remove a naturalised person or dual-nationality-holder’s British citizenship if it was considered “conducive to the public good”, but a 1981 law prevented them from doing so if it made the person stateless. Since 9/11, that restraint has been gradually abandoned.

In 2006, the home secretary was given further powers to revoke British citizenship. At the time, the government sought to allay concerns about misuse of these powers. “The secretary of state cannot make an order on a whim,” the home office minister Angela Eagle had said when the law was first proposed, “and he will be subject to judicial oversight when he makes an order”.

Although the post-9/11 measures were initially presented as temporary, they have become permanent. And the home secretary can strip people of their citizenship without giving a clear reason. No court approval is required, and the person concerned does not need to have committed a crime. The practice is growing. Under Labour, just five people had their citizenship removed, but when Theresa May was at the Home Office, 70 people were stripped of their citizenship, according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Yet these near-arbitrary powers have caused remarkably little concern.

*****

People have largely accepted these new powers because they are presented as a way to keep the country safe from terrorism. After 9/11, the public became more aware of the Islamist preachers who had made London their home in the preceding decades. Abu Hamza, who was then the imam of Finsbury Park mosque, and became a notorious figure in the media, was, like me, a naturalised British citizen. For several years as a teenager, I attended the Finsbury Park mosque. It was small; I remember the smell of tea, incense and feet that greeted you every time you walked in. I also remember the eclectic mix of worshippers who visited – Algerians, Afghans, Somalis and Moroccans. Unlike Muslims of south-Asian background, few of these people had longstanding colonial ties to Britain. Most had fled civil war in their home countries, while some of the North Africans had left France because they felt it treated Muslims too harshly. The mosque was not affiliated with the Muslim Association of Britain, and its preachers promoted a Salafi form of Islam.