Andy Worthington's Blog, page 23

June 10, 2019

Quarterly Fundraiser: Seeking $2500 (£2000) to Support my Guantánamo Work, Activism and Photo-Journalism for the Next Three Months

A photo of me calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay in Washington, D.C. on January 11, 2019, the 17th anniversary of its opening, when it had been open for 6,210 days.

A photo of me calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay in Washington, D.C. on January 11, 2019, the 17th anniversary of its opening, when it had been open for 6,210 days.Please click on the ‘Donate’ button below to make a donation towards the $2,500 (£2,000) I’m trying to raise to support my work on Guantánamo over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Dear friends and supporters,

Every three months I ask you, if you can, to make a donation to support my work as a freelance journalist and activist, working primarily to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay, but also working on social justice issues in the UK, particularly involving housing and the environment, as well as chronicling the changing face of London in my ongoing photo-journalism project ‘The State of London.’

It’s now 12 years since I began publishing articles about Guantánamo on my website, after I had completed the manuscript for my book The Guantánamo Files, published in 2007. Since then, I have published nearly 2,300 articles about Guantánamo, telling the stories on the men held, and campaigning to secure the closure of the prison, which remains, as it always has been, a legal, moral and ethical abomination. Since 2012, I have also been augmenting my work here with the very specific focus of the Close Guantánamo campaign and website.

If you can make a donation to support my ongoing efforts to close Guantánamo, please click on the “Donate” button above to make a payment via PayPal. Any amount will be gratefully received — whether it’s $500, $100, $25 or even $10 — or the equivalent in any other currency.

You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make this a monthly donation,” and filling in the amount you wish to donate every month, and, if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.

The donation page is set to dollars, because the majority of my readers are based in the US, but PayPal will convert any amount you wish to pay from any other currency — and you don’t have to have a PayPal account to make a donation.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (to 164A Tressillian Road, London SE4 1XY), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send cash from anywhere else in the world, that’s also an option. Please note, however, that foreign checks are no longer accepted at UK banks — only electronic transfers. Do, however, contact me if you’d like to support me by paying directly into my account.

On Guantánamo, of course, the arrival of Donald Trump in the White House in January 2017 was a disaster, as he has no desire to release anyone or to close the prison, and it remains an uphill struggle to try to keep Guantánamo in the public eye, especially as the many other crimes of Trump and the Republicans are so time-consuming. Nevertheless, it remains imperative that the shame of Guantánamo is not forgotten, and I hope you will be able to support me as I keep making the case for why the prison must be closed once and for all, and providing examples of its long history of lawlessness, brutality and injustice — like the article I posted yesterday on the 13th anniversary of the deaths of three men at the prison in June 2006, who should not be forgotten.

Elsewhere, I appreciate those who support my campaigning against cynical housing development projects in London, a form of social cleansing that should be seen as a war on the poor, if the mainstream media took an interest in it, which they generally don’t. Since 2017, I have been committed to a campaign in Deptford, in south east London, close to where I live, which has involved trying to prevent the destruction of a precious community garden (which was also a vital environmental protection against pollution) and structurally sound council housing, with the campaign attracting wide support, both in and of itself, but also because it is a microcosm of the problems with the housing regeneration industry. I have also been writing regularly about housing issues for the last few years, on the same reader-supported basis as my Guantánamo work.

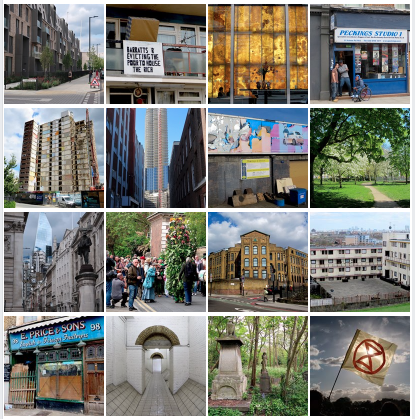

And on a final front of reader-supported business, I’d also like to thank those of you who follow ‘The State of London’ and to ask for your support. The photo-journalism project, which I started over seven years ago, involves me cycling every day and taking photos, often in my local neighbourhood, but, on average, making journeys across the capital’s 120 postcodes at least a couple of times a week, and posting a photo a day, with detailed supporting text, on social media. Do check it out, if you haven’t seen it already, and feel free to support me if you like what you see.

With thanks, as ever, for your interest in my work, regardless of whether or not you can support me financially. Without you, none of this would mean anything.

Andy Worthington

London

June 10, 2019

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign.

June 9, 2019

13 Years Ago, Three Men Died at Guantánamo, Victims of a Brutal Regime of Lawlessness That Is Fundamentally Unchanged Today

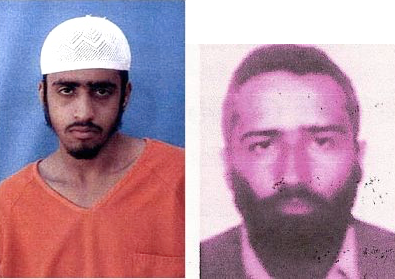

Yasser al-Zahrani and Ali al-Salami, two of the three men who died at Guantánamo on the night of June 9, 2006, in circumstances that remain deeply contentious. The US authorities insist that they committed suicide, but other troubling accounts have robustly questioned that conclusion. No photo publicly exists of the third man, Mani- al-Utaybi.

Yasser al-Zahrani and Ali al-Salami, two of the three men who died at Guantánamo on the night of June 9, 2006, in circumstances that remain deeply contentious. The US authorities insist that they committed suicide, but other troubling accounts have robustly questioned that conclusion. No photo publicly exists of the third man, Mani- al-Utaybi.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

On the night of June 9, 2006, three prisoners at Guantánamo died, their deaths shockingly and insensitively described by the prison’s then-commander, Adm. Harry Harris Jr., as “an act of asymmetrical warfare against us.”

The three men were Yasser al-Zahrani, a Saudi who was just 17 when he was seized in Afghanistan in December 2001, Mani al-Utaybi, another Saudi, and Ali al-Salami, a Yemeni. All three had been prominent hunger strikers.

Al-Zahrani, the son of a prominent Saudi government official, was a survivor of the Qala-i-Janghi massacre, which John Walker Lindh, the “American Taliban,” who was recently released after 17 years in a US prison, also survived. Over 400 fighters, supporting the Taliban, had been told that if they surrendered, they would then be set free, but it was a betrayal. They were taken to a fort, Qala-i-Janghi, run by General Rashid Dostum, one of the leaders of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance, where some of the men, fearing they would be killed, started an uprising with concealed weapons. Over the course of a week, the prisoners were bombed, set on fire, and, finally, flooded out of a basement, and when they finally emerged, only 86 of the original prisoners had survived.

In Guantánamo, he was remembered fondly by his fellow prisoners, but the authorities noted a history of him being “non-compliant and hostile to the guard force and staff.” However, he was regarded as having little or no intelligence value, and his classified military file, dated March 2006 and released by WikiLeaks in 2011, noted that, “If a satisfactory agreement can be reached that ensures continued detention and allows access to detainee and/or to exploited intelligence, detainee can be Transferred Out of Control” of the Guantánamo authorities and back to Saudi Arabia (which, in reality, would have meant him being repatriated and put through Saudi Arabia’s rehabilitation program for jihadists, like numerous other Saudi prisoners).

Mani al-Utaybi, who was around 30 when he died, had been in Pakistan undertaking missionary work with Talbighi Jamaat, a vast proselytizing organization, and there is no evidence that he was anywhere near the battlefields of Afghanistan. He was seized in January 2002, near the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan, with four other men, all dressed in burkas, who seem to have taken it up on themselves to try to get into Afghanistan in an absurd and thwarted bid to assist the resistance to the US occupation.

Described by the US authorities as having been “belligerent, argumentative, harassing, and very aggressive,” he was also worthless from an intelligence perspective, and, in June 2005, had been cleared to be “transferred to the control of another country for continued detention” (which, as with al-Qahtani, would have meant the Saudi rehabilitation program).

The third man, Ali al-Salami, around 23 years old at the time of his capture, had also been regarded as “aggressive” at Guantánamo, but was also, according to the US authorities, thoroughly insignificant in terms of his intelligence value, “a street vendor who sold clothing,” and “was prompted to travel to Pakistan to receive [a religious] education upon hearing God’s calling.” As with al-Utaybi, there is no allegation that he was anywhere near the battlefields of Afghanistan. He had been studying in Faisalabad at Jamea Salafia University, a madrassa (religious school), but had been living in a dormitory that was allegedly connected to Abu Zubaydah.

The facilitator of an independent training camp, Khaldan, Abu Zubaydah arranged the comings and goings of those seeking military training in Afghanistan, but the CIA mistakenly regarded him as Al-Qaeda’s No. 3, ignoring the FBI, who knew that he was not only not al-Qaeda’s no. 3, but he wasn’t even a member of al-Qaeda at all. On capture, he was flown to a secret CIA “black site” in Thailand, where he became the first victim of the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program, and was waterboarded on 83 separate occasions. He was later moved to other “black sites” in eastern Europe, before being brought to Guantánamo, with 13 other alleged “high value detainees,” also held in CIA “black sites,” in September 2006, were he has continued to be held, largely incommunicado, ever since.

The dormitory — known as the Crescent Mill guest house — was raided on the same night that the house Abu Zubaydah was staying in was also raided, when al-Salami and 15 other men were seized, but although the US authorities tried to tie them to al-Qaeda, it was fruitless task, and they have all since been freed — except for al-Salami, of course. For a devastating analysis, by a US judge, of the paucity of the US’s claims about those seized in the guest house, see my 2009 articles, Judge Condemns ‘Mosaic’ Of Guantánamo Intelligence, And Unreliable Witnesses and Guantánamo: A Prison Built On Lies.

Investigating the deaths

The US authorities have always stuck to their line about the men’s deaths, even though others have questioned whether the men killed themselves, or whether they were, in fact, deliberately killed by operatives of the US government, or accidentally killed as a result of a torture session that went too far.

The most prominent dissenter from the official line is former Staff Sgt. Joe Hickman, who was in charge of the watch towers on the night of the deaths. Hickman’s account of the deaths, which he bottled up until Barack Obama became president, thinking that it might lead to the truth being exposed, was first reported in Harper’s Magazine, in an article entitled, “The Guantánamo Suicides,” by the lawyer and journalist Scott Horton, in January 2010.

In it, Hickman was reported as stating that frantic activity in response the men’s deaths followed the movement of vehicles to and from the direction of a shadowy facility that he and other personnel had dubbed “Camp No,” because whenever they asked about it, they were told that it didn’t exist. It was Hickman who suggested that,. on the night of the deaths, the men had either been deliberately, or accidentally killed in this facility away from the main base.

However, hopes that Hickman’s account would lead to an honest, impartial investigation were dashed. The Justice Department, which initially expressed interest in it, dropped an investigation before the Harper’s article was published.

Hickman later wrote a book about the alleged suicides, Murder At Camp Delta, which was published in January 2015, and he was also the lead investigator on a 2013 report, “Uncovering the Cover-Ups,” by The Center For Policy and Research at Seton Hall University School of Law, whose director, Mark Denbeaux, had been Hickman’s first port of call when he decided to go public. The report forensically went through documentation released following a report on the deaths by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), which found it to be full of glaring holes.

For a detailed article following up on all of the above, please check out “To Live and Die in Gitmo”, published in Newsweek to coincide with the publication of Hickman’s book, and written by Alexander Nazaryan.

As a result of the refusal of the authorities to revisit the alleged suicides, the events of June 9-10, 2006 still remain deeply contentious, even though “Camp No” has subsequently come into sharper focus, as it has been revealed that there were two facilities outside of the control of the US military at Guantánamo — Strawberry Fields and Penny Lane, named after two celebrated songs by the Beatles.

Strawberry Fields was a CIA “black site” from the fall of 2003 until spring 2004, when it was moved because the authorities recognized that a US judge was about to grant habeas corpus rights to the prisoners, allowing lawyers into the prison, piercing the veil of secrecy required for Guantánamo’s brutality to go unnoticed.

Penny Lane, meanwhile, was where double agents from the prison’s population were groomed, or, as Alexander Nazaryan put it, “its purpose was supposedly to turn detainees into CIA assets who could infiltrate jihadist networks.” He added that it “appears to have been shuttered for about four months after the three men died.”

According to Joe Hickman’s assessment, it was at this facility that, on the night of the men’s deaths, they were subjected to a torture session that involved what has become known as “dry-boarding,” in which they had rags stuffed down their throats. That would certainly explain what otherwise remains one of the great stumbling blocks to accepting the US authorities’ account of the deaths: how, to paraphrase Alexander Nazaryan, the three men had managed to stuff rags down their own throats, tie their feet together, tie their hands together, create a noose, climb up onto the cell’s sinks, put the noose around their neck, and then jump with sufficient force to die by self-inflicted strangulation, all while shielding their activities from the guards, who were supposed to persistently keep a watch on the cells.

In the years since Joe Hickman first surfaced with his account, it — and Scott Horton’s Harper’s article — have been criticized by some commentators, and, in general , dismissed out of hand by representatives of the US government. However, on re-reading Alexander Nazaryan’s article, I was struck by the following paragraph: “A highly placed source in the Department of Defense who deals with detainees’ affairs, and who asked to remain anonymous because he is not permitted to speak to the media without receiving prior clearance, wrote to me in an email: ‘After reviewing the information concerning the three deaths at Camp Delta on June 9, 2006, it is painfully apparent the personnel involved in fact created an illusion of an investigation. When you consider the missing documents, the lack of key interviews, and the questionable evidence found on the bodies, it is blatantly obvious there was something that occurred that night that is not documented.’”

A damning conclusion

13 years on from the deaths, as I make my annual effort to not let them be forgotten, what strikes me as the most depressing aspect of this sad and unresolved episode in Guantánamo’s long and depressing history is how three men, none of whom had any kind of intelligence value, died at Guantánamo, whether by accident or design, not because of what they had done prior to their capture, but because they had responded with resistance to the appalling ways in which they were treated after capture.

Think about that: three men died at Guantánamo, not because of what they had done prior to their capture, but because, in the pointless brutality of Guantánamo’s grinding, dispiriting, day-to-day existence, they had either killed themselves, in despair at how very far they had ended up from any notion of justice whatsoever, or, even more damningly, because, in resisting that endless injustice, they had angered the authorities to such an extent that they were killed.

Remember too that 40 men are still held at Guantánamo, and that, although some are regarded as significant terrorist suspects, others are still held because they, like the men who died on the night of June 9, 2006, refused to passively accept the injustice of Guantánamo, engaging in hunger strikes and non-compliant behavior, even though they too were nothing more than, at most, insignificant foot soldiers from a long-forgotten war, with no intelligence value and no good reason for their ongoing imprisonment, seemingly for the rest of their lives, without charge or trial.

Note: There have, officially, been nine deaths at Guantánamo since the prison opened on January 11, 2002, and some of those other deaths — also of long-term hinger strikers — are also suspicious. For further information, please check out the links in my article about the deaths from last June, and a detailed report from this year about Haji Naseem, who died in 2011, by Jeffrey Kaye, an investigative journalist and retired psychologist, who has been extraordinarily tenacious in his pursuit of the truth about several of the deaths at Guantánamo.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 5, 2019

The Long Persecution of John Walker Lindh, the “American Taliban”

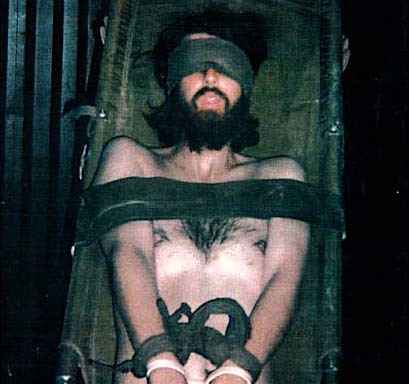

John Walker Lindh, strapped to a gurney in Camp Rhino, near Kandahar, after his capture in December 2001, when he had already survived a massacre at the Qala-i-Janghi fort.

John Walker Lindh, strapped to a gurney in Camp Rhino, near Kandahar, after his capture in December 2001, when he had already survived a massacre at the Qala-i-Janghi fort.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

The US establishment is nervous about John Walker Lindh, the “American Taliban.”

A US citizen, Lindh was taken into custody by US forces in Afghanistan in December 2001, along with around 85 other Taliban fighters, survivors of a massacre — the Qala-i-Janghi massacre — that is largely forgotten. He received a 20-year prison sentence in a federal court on the US mainland in May 2002 for providing material support to terrorism, but had his sentence reduced by three years because of good behavior.

He was released on May 23, but with restrictions imposed by a federal judge. As the Associated Press described it, “Lindh’s internet devices must have monitoring software; his online communications must be conducted in English; he must undergo mental health counseling; he is forbidden to possess or view extremist material; and he cannot hold a passport or leave the US.”

Donald Trump opposed his early release, as did Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. It was reported back in 2015 that, from prison, he had expressed support for Daesh (aka Islamic State or Isis). For the Atlantic, staff writer Graeme Wood, based on prison correspondence with Lindh, claimed that he was “permanently devoted” to violent jihad, and that “public security demands nothing less than close observation [of Lindh] for a very, very long time.”

Unhelpfully, the BBC’s “shock horror” headline was “John Walker Lindh: What happens when you release a ‘traitor’?” They and other outlets (the Washington Post, CNN) worried about what they perceived to be the lack of a de-radicalization program in the US for those released from prison after being convicted of crimes related to terrorism, but all these worries seem exaggerated to me. Lindh faces restrictions on his use of technology, and has no passport.

Other commentators wrote about his alleged involvement in the death of CIA operative Mike Spann, shortly after he and the other prisoners were taken to Qala-i-Janghi.

To understand what happened, we need to revisit the situation in December 2001, as hundreds of Taliban fighters, mainly from the Gulf, but also from Pakistan, north Africa and other countries, who had joined the country’s long-running civil war with the Northern Alliance, surrendered after the fall of the city of Kunduz.

They had been told, by a Taliban general, that they would subsequently be freed, but they were, instead, taken to Qala-i-Janghi, a large, well-fortified mud fort under the control of Gen. Rashid Dostum, a leader of the Northern Alliance.

Some of these men, however, had hidden grenades, one of which killed Spann. The suggestion was that Lindh knew the men were armed, but there is no evidence that this is the case.

What most news reports are failing to mention, however, is that in response to what is generally called the “uprising,” the survivors were bombed, set on fire, and, finally, flooded out of a basement over the course of a week.

As far as we know, perhaps as many as 400 prisoners died as a result of these various strategies, and all the survivors — around 86 men (and boys) in total — were sent to Guantánamo, making up over 10% of the prison’s total population over the years, and where, eventually, the authorities worked out that they were more or less irrelevant foot soldiers.

One exception is Lindh, for whom the Guantánamo prison number ISN 001 was reserved, but was never used — because Guantánamo is strictly only for non-US citizens.

Lindh was subjected to specific abuse because he was American, as I explained in an article about him in 2011, when I stated that, after capture, “he had been moved to Camp Rhino near Kandahar, where he was stripped naked, blindfolded, bound to a stretcher with duct tape, held in a shipping container ringed with barbed wire and interrogated by the US military and the CIA, who reported regularly to Donald Rumsfeld (and where soldiers scrawled ‘shithead’ on his blindfold and told him he would be hanged).” He was also held on two ships (the USS Peleliu and the USS Bataan), and was brought to the US on January 22, 2002, and charged on February 5 on ten charges relating to his alleged involvement with al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

As I also explained at the time, “In July 2002, Lindh was persuaded to accept a plea deal, which not only gagged him throughout his sentence and prevented him from challenging anyone in authority about his shameful abuse in US custody prior to his trial, but also led to a punitive 20-year sentence, announced on October 4, 2002”, at the high-security Federal Correctional Institution at Terre Haute, Indiana, in one of a number of Communication Management Units (CMUs), quite severely isolated environments for mainly Muslim prisoners, whose existence has come under intense criticism from human rights activists, as I explained in two cross-posted articles in 2011, via NPR and the Nation.

In 2009, an article for GQ explained the “special administrative measures” Lindh was subjected to in the CMU: “no mail, no nonfamily visitors, no Arabic.” The SAMs were “unilaterally imposed on John by then Attorney General John Ashcroft”, and, as the author of the article, John Rico, proceeded to explain, “It was designed to ensure that John Walker Lindh not speak, not share his story, not inspire potential followers, and not describe his treatment while in the custody of the US government.”

Rico added, “It was an order of uncertain legal merit (not unlike George W. Bush’s presidential signing statements), but because John was initially deemed an enemy combatant — a brave new legal status of undetermined meaning” — it was, as of 2009, “an order to which Frank and his son’s attorneys [were] careful to comply, lest they risk[ed] John being held after his prison sentence ha[d] ended. So until 2021 — now, presumably, 2019, although is no suggestion that Lindh will speak out publicly — nothing John Walker Lindh said could be “communicated to the outside world.”

As I noted above, I find it hard to imagine Lindh posing any kind of threat with limited access to technology and no passport, but if the government is concerned they can presumably keep him under old-school surveillance — although I realise that it costs money to actually hire people to watch someone, a seemingly unpopular route for western governments in an age of permanent electronic surveillance.

Most of all, however, I wonder about the disconnect between Lindh’s alleged ongoing extremism, and the way in which his captors seemingly did nothing to try to rehabilitate him, and, instead, kept him in a situation that, presumably, would have a tendency to reinforce extremism rather than to challenge it.

I hope John Walker Lindh gets a chance to see what else life might be, as someone now 38 years old, and with 17 long years lost to prison. He is, after all, no longer the teenager who sought out jihad, captured when he was just 20 years old. As former prisoner Moazzam Begg explained to the AP after his release, “the criticism over Lindh’s early release is misguided. If anything, Lindh was imprisoned too long.”

Begg made a point of noting, accurately, that “many of the other Taliban fighters who were sent to Guantánamo as enemy combatants were released much earlier.”

As for Lindh’s letter in support of the Islamic State, Begg “noted that it was written four years ago and that Lindh might not have had full knowledge of the group’s atrocities from behind bars.” As he put it, “Nobody really knows what his views are right now in 2019.”

In a statement, Begg added, “It is now time for him to be allowed to restart his life in peace and freedom.”

I second that suggestion — and would like to note, in closing, that, although Lindh’s long sentence was harsh, at least it is now over, while the ordeal of the men still held at Guantánamo continues, with no end in sight, even though some of the 40 men still held were no more significant than Lindh was.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 1, 2019

34 Years On from the Battle of the Beanfield, Is Widespread Environmental Dissent Conceivable?

A photo from the Battle of the Beanfield on June 1, 1985, when the government of Margaret Thatcher violently decommissioned a convoy trying to get to Stonehenge to set up what would have been the 12th annual Stonehenge Free Festival.

A photo from the Battle of the Beanfield on June 1, 1985, when the government of Margaret Thatcher violently decommissioned a convoy trying to get to Stonehenge to set up what would have been the 12th annual Stonehenge Free Festival.Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

It’s 34 long years since the boot of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain crushed one of the most visible demonstrations of counter-cultural dissent in the UK via a brutal demonstration of the violence of the establishment at what became known as the Battle of the Beanfield, when 1,400 police — from six counties and the MoD — shut down a vastly outnumbered convoy of nomadic new age travellers, anarchists, environmental activists and free festival stalwarts as they attempted to get to Stonehenge to establish what would have been the 12th annual Stonehenge Free Festival.

From humble origins in 1974, the festival grew — reflecting massive discontent in Thatcher’s Britain, where unemployment was at an all-time high in the early ‘80s — so that by the time it was suppressed, tens of thousands of people, for the whole of June, set up a makeshift settlement, the size of a small town, in the fields opposite Stonehenge.

Drug use was rife, as was acid rock music, while the festival’s regulars, who took part in a circuit of free festivals in England and Wales from May to September, tried to get by via the creation of a low-level, low-impact economy that, like their decision to take to the road in old vehicles rather than stagnating on the dole in towns and cities without jobs, fundamentally challenged the state’s insistence that nomadic activities were reserved solely for Gypsies, who, themselves, have a long history of persecution, as settled people generally, it seems, despise nomadic people.

The convoy also, unacceptably from the state’s point of view, confronted the establishment’s claimed land rights, embraced environmental awareness in contrast to corporate materialism, and opposed nuclear power and nuclear weapons, both of which were endorsed by Thatcher and the Tories.

While the state’s brutality dealt a serious blow to the coherence of the traveller and festival movement, it wasn’t enough to stifle dissent. I had visited the Stonehenge Free Festival as a student in 1983 and 1984, and it had a transformational effect on me. News of the Beanfield was genuinely shocking, as was the suppression of the festival, and the passing of new laws, in the 1986 Public Order Act, that were designed to cripple the ability of any group of perceived troublemakers to gather freely, but it was foolish of the Tories to believe that they could prevent active and vocal criticism of Thatcher’s vision of a new privatised Britain of unfettered banking and rabid materialism.

A new drug, ecstasy, soon emerged to create a loved-up party scene involving huge and illegal warehouse raves, which soon attracted survivors of the traveller and festival scene, creating new counter-cultural hybrids, the culmination of which was the last Stonehenge-sized free festival, on Castlemorton Common in Gloucestershire, over the Whitsun Bank Holiday weekend in May 1992, where all the many tribes came together — boy racers from the Home Counties meeting the crusty encampments of the Brew Crew, as rave sound systems played 24/7.

That prompted a further clampdown, via 1994’s Criminal Justice Act, with its absurd efforts to ban music characterised by “a series of repetitive beats,” and further, draconian bans on unlicensed gatherings, as well as the effective criminalisation of trespass, but what no one saw coming was a broad protest movement that saw the earth as sacred, and that involved protestors occupying trees, digging tunnels and working out how to lock themselves on to equipment to prevent the creation of roads and bypasses.

In 1993-94, a huge battle of resistance took place in east London, to try to prevent the creation of the M11 Link Road, and in the meantime another urban expression of dissent came about via Reclaim the Streets, which blocked roads and held parties in spaces that were suddenly car-free and autonomous.

These movements in turn fed into the huge anti-globalisation movement of the late ‘90s and early 2000s, and the Occupy movement of 2011-12, when public space was once more occupied, and the prevailing economic system was dissected and found wanting. Nevertheless, the prevailing trend in the 21st century has been for the corporate world to consolidate its power, turning populations into docile consumers, and trapping as many people as possible in insanely expensive housing so that, in theory, they — we — are too tied up and distracted to rise up.

Sadly, this has been largely successful, but it requires serious levels of employment to work well, and decent jobs, meanwhile, are drying up, through outsourcing, mechanisation and A.I. advances. As those falling through a deliberately frayed safety net — part of the cynical “age of austerity” implemented by the Tories in response to the banker-led global economic crash of 2008 — drop off the system’s radar, they are forced to find ways to subsist peripherally, living on the streets, permanently crashing at the houses of friends, as so-called “sofa surfers”, in tents, in cars or vans, in caravans, or through squatting in empty industrial buildings, which are the only buildings that can now be successfully squatted, after the Tories, disgracefully, made squatting in empty houses a criminal, rather than a civil offence.

In some crucial ways, the situation is similar to that which created a growing traveller movement in the early ‘80s, under Thatcher, but now, of course, people can’t easily sign on and live largely without scrutiny, and the cheap vehicles of the ‘80s no longer exist. Many of the counter-cultural impulses, however, live on, and after the long drought in serious dissent that preceded the Occupy movement, a similarly long subsequent drought in opposing the status quo had to wait until last October, when Extinction Rebellion (XR) announced itself via the simultaneous occupation of five central London bridges.

As someone who has lived through, and taken part in the various counter-cultural movements from the free festivals to the road protest movement to the anti-globalisation protests and the Occupy movement, I was intrigued by the thought that had gone into XR’s efforts at mass mobilisation and mass dissent — disrupting “business as usual” via scrupulously non-violent direct action, and, more contentiously seeking mass arrests, to highlight the unprecedented man-made environmental crisis we currently face, and when, in April, campaigners occupied four central London sites for a week — Waterloo Bridge, Oxford Circus, Parliament Square and Marble Arch — it felt very much as though a spark drawing inspiration from the extraordinary Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common, the road protest movement, the anti-globalisation movement and Occupy had been re-ignited, that, this time, might lead to significant system change.

I don’t mean to sound naive about the state’s desire and ability to mobilise in resistance to any efforts to break the current state of business, but what XR — and the powerful figure of 16-year old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg and the school strike for climate movement she inspired — have that none of our previous movements have been able to achieve is a global sense of absolute emergency. We are, to be blunt, already killing the planet as a sustainable entity for humans, and, for the first time, large numbers of people seem to be waking up to the painful truth that, if we don’t embrace a complete, revolutionary change in the way that we deplete and consume the world’s resources, fill the planet with plastic, and pump out carbon dioxide, we face a dangerously super-heated atmosphere and the total collapse of civilisation as we know it not only within our lifetimes, but possibly within the next ten years.

34 years on, gazing back in time to the Battle of the Beanfield is in many ways a sad indicator of quite how much the world has changed in the intervening decades, with hectic over-consumption, self-absorption and self-entitlement at unprecedented levels, but those of us who have never settled for dystopian materialism as meaningful or worthwhile need to remember that what was being sought back then, and is still being sought now, is more important than ever, and that the struggle for a less rapacious and more sustainable world can still be won, and, indeed, must be won, because nothing less than the very future of humanity is at stake.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 31, 2019

Stop the Extradition: If Julian Assange Is Guilty of Espionage, So Too Are the New York Times, the Guardian and Numerous Other Media Outlets

An undated photo of a billboard outside the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, criticizing efforts by the US to punish Chelsea Manning and Julian Assange for having leaked and published classified US government documents.

An undated photo of a billboard outside the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, criticizing efforts by the US to punish Chelsea Manning and Julian Assange for having leaked and published classified US government documents.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Nearly seven years ago, when WikiLeaks’ founder, Julian Assange, sought asylum in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London (on June 19, 2012), he did so because of his “fears of political persecution,” and “an eventual extradition to the United States,” as Arturo Wallace, a South American correspondent for the BBC, explained when Ecuador granted him asylum two months later. Ricardo Patino, Ecuador’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, spoke of “retaliation that could endanger his safety, integrity and even his life,” adding, “The evidence shows that if Mr. Assange is extradited to the United States, he wouldn’t have a fair trial. It is not at all improbable he could be subjected to cruel and degrading treatment and sentenced to life imprisonment or even capital punishment.”

Assange’s fears were in response to hysteria in the US political establishment regarding the publication, in 2010 — with the New York Times, the Guardian and other newspapers — of war logs from the Afghan and Iraq wars, and a vast number of US diplomatic cables from around the world, and, in 2011, of classified military files relating to Guantánamo, on which I worked as media partner, along with the Washington Post, McClatchy, the Daily Telegraph and others. All these documents were leaked to WikiLeaks by former US Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning.

Nearly seven years later, Assange’s fears have been justified, as, on May 23, the US Justice Department charged him on 18 counts under the Espionage Act of 1917, charges that, as the Guardian described it in an editorial, could lead to “a cumulative sentence of 180 years.”

The charges came six weeks after the Ecuadorian government — under new, pro-US leadership — withdrew Assange’s asylum, leading to his immediate arrest by British police and his unacceptable imprisonment in Belmarsh, a maximum-security prison that is supposed to hold only dangerous convicted criminals, although it has also, since the “war on terror” began, been used to hold alleged terrorism suspects without charge or trial.

That same day, the US began extradition proceedings, after unsealing a 2018 indictment against him “in connection with a federal charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion,” as the Justice Department described it, relating to alleged efforts to assist Chelsea Manning to “crack an encoded portion of a passcode that would have enabled her to log on to a classified military network under a different user name than her own, which would have masked her tracks better,” as the New York Times described it. Noticeably, Justice Department lawyers “have not alleged that his efforts succeeded,” and in any case the charge only carries a maximum sentence of five years.

Clearly, though, that charge was just to pave the way for the indictment unveiled last week, which has, understandably, appalled defenders of free speech, enshrined in the US in the First Amendment.

Among the many powerful rebukes to the Trump administration and the Justice Department, Glenn Greenwald’s column in the Washington Post three days ago, “The indictment of Assange is a blueprint for making journalists into felons,” provides a commendable summary.

Greenwald notes that, although the US government “has been eager to prosecute Assange since the 2010 leaks,” up until now “officials had refrained because they concluded it was impossible to distinguish WikiLeaks’ actions from the typical business of mainstream media outlets.”

“With these new charges,” however, “the Trump administration is aggressively and explicitly seeking to obliterate the last reliable buffer protecting journalism in the United States from being criminalized, a step that no previous administration, no matter how hostile to journalistic freedom, was willing to take.”

Dismissing dangerous claims that Assange “isn’t a journalist at all and thus deserves no free press protections,” Greenwald also explains that “this claim overlooks the indictment’s real danger and, worse, displays a wholesale ignorance of the First Amendment.” As he further explains:

Press freedoms belong to everyone, not to a select, privileged group of citizens called “journalists.” Empowering prosecutors to decide who does or doesn’t deserve press protections would restrict “freedom of the press” to a small, cloistered priesthood of privileged citizens designated by the government as “journalists.” The First Amendment was written to avoid precisely that danger.

Most critically, the US government has now issued a legal document that formally declares that collaborating with government sources to receive and publish classified documents is no longer regarded by the Justice Department as journalism protected by the First Amendment but rather as the felony of espionage, one that can send reporters and their editors to prison for decades. It thus represents, by far, the greatest threat to press freedom in the Trump era, if not the past several decades.

If Assange can be declared guilty of espionage for working with sources to obtain and publish information deemed “classified” by the US government, then there’s nothing to stop the criminalization of every other media outlet that routinely does the same — including the Washington Post, as well as the large media outlets that partnered with WikiLeaks and published much of the same material in 2010, along with newer digital media outlets like the Intercept, where I work.

As Greenwald also explains, “The vast bulk of activities cited by the indictment as criminal are exactly what major US media outlets do on a daily basis,” adding:

Outside the parameters of the Trump DOJ’s indictment of Assange, these activities are called “basic investigative journalism.” Most major media outlets in the United States, including the Post, now vocally promote Secure Drop, a technical means modeled after the one pioneered by WikiLeaks to allow sources to pass on secret information for publication without detection. Last September, the New York Times published an article (titled “How to Tell Us a Secret”) containing advice from its security experts on the best means for sources to communicate with and transmit information to the paper without detection, including which encrypted programs to use.

Many of the most consequential and celebrated press revelations of the past several decades — from the Pentagon Papers to the Snowden archive (which I worked on with the Guardian) to the disclosure of illegal War on Terror programs such as warrantless domestic NSA spying and CIA black sites — have relied upon the same methods that the Assange indictment seeks to criminalize: namely, working with sources to transmit illegally obtained documents for publication.

Stop the extradition

It cannot be said with any certainty that the charges against Assange will lead to a successful prosecution in the US, but the best way of making sure that it doesn’t happen would be for the British government to refuse to extradite him, which it is perfectly entitled to do; in fact, under the terms of the US-UK Extradition Treaty, it is required not to agree to the request, because the treaty explicitly states that “[e]xtradition shall not be granted if the offense for which extradition is requested is a political offense.”

Whether the British government will comply with this requirement is another matter. Holding him in Belmarsh seems to me to reveal the contempt with which they regard him, but even so it will be difficult for the British government to ignore what the Guardian described as the near-certainty that his “treatment in the American penal system would be more cruel than anything he might encounter even in our shameful prisons.”

That said, Assange has clearly already been suffering in Belmarsh, as two nights ago he was moved to the hospital wing of Belmarsh after what WikiLeaks’ website described as a “dramatic” loss of weight and deteriorating health, prompting “grave concerns” about his well-being.

“Mr Assange’s health had already significantly deteriorated after seven years inside the Ecuadorian Embassy, under conditions that were incompatible with basic human rights,” WikiLeaks said in a statement, adding, “During the seven weeks in Belmarsh his health has continued to deteriorate and he has dramatically lost weight. The decision of prison authorities to move him to the ward speaks for itself.”

WikiLeaks also stated that, as the Evening Standard put it, “he could barely talk” when he met his lawyer, Per Samuelson, last Friday. Samuelson said that the state of his health was so poor that “it was not possible to conduct a normal conversation with him.”

Today, that analysis has been reinforced by Nils Melzer, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Torture, who visited him in prison “earlier this month in the company of medical experts who examined him,” as the Guardian explained. Melzer said, “Julian Assange is showing all the symptoms associated with prolonged exposure to psychological torture and should not be extradited to the US.”

Commenting on his visit with Assange, he said, said, “Physically there were ailments but that side of things are being addressed by the prison health service and there was nothing urgent or dangerous in that way. What was worrying was the psychological side and his constant anxiety. It was perceptible that he had a sense of being under threat from everyone. He understood what my function was but it’s more that he was extremely agitated and busy with his own thoughts. It was difficult to have a very structured conversation with him.”

Noticeably, Chelsea Manning, who, unlike the Trump administration and the Justice Department, is fully aware of the difference between those who leak classified information for the public good, and those who publish it, and who is currently imprisoned for refusing to cooperate with a Grand Jury investigating Assange, after being imprisoned for seven years during the Obama presidency, released a statement from jail on the day Assange was charged with espionage in which she said she accepted “full and sole responsibility” for the 2010 WikiLeaks disclosures.

“It’s telling that the government appears to have already obtained this indictment before my contempt hearing last week,” Manning said, adding, “This administration describes the press as the opposition party and an enemy of the people. Today, they use the law as a sword, and have shown their willingness to bring the full power of the state against the very institution intended to shield us from such excesses.”

Yesterday, former Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger joined the calls by high-ranking journalists and defenders of press freedom for Assange not to be prosecuted under the Espionage Act, which he described as “a panic measure enacted by Congress to clamp down on dissent or ‘sedition’ when the US entered the First World War in 1917.”

“Whatever Assange got up to in 2010-11,” Rusbridger notes, “it was not espionage.”

When Assange was first arrested by British police, I posted a link to the page on WikiLeaks’ website showing all the media partners it has worked with over the years. What is needed now is for everyone concerned with press freedom — with, in the US, the cherished First Amendment — to declare unconditionally that the charges are wrong, and that the UK should not extradite Assange to the US.

And while they’re at it, they might also want to point out that holding a journalist without charge or trial in Britain’s most notorious prisons for convicted criminals is not an act of justice, but one of vengeance.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 28, 2019

European Elections: Pro-Remain Parties More Successful Than the Brexit Party, While 63% of Electorate Fail to Vote At All

A graph on the BBC website showing how Remain voters outnumbered Leave voters in the UK’s elections to the European Parliament on May 23, 2019.

A graph on the BBC website showing how Remain voters outnumbered Leave voters in the UK’s elections to the European Parliament on May 23, 2019. Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

I wanted to make sure that I contributed my own analysis to the results of the election of MEPs to the European Parliament last Thursday, before the mainstream media’s juggernaut of distraction and distortion takes over.

The first key conclusion is that, although, out of nowhere, the slimy reptilian Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party took 31.6% of the vote, the Brexit Party (and UKIP’s rump vote, taking the total Leave votes to 34.9%) were outnumbered by pro-Remain parties — primarily via the Liberal Democrats on 20.3%, the Greens on 12.1%, and the SNP, Change UK and Plaid Cymru adding another 8% — 40.4% in total.

The second key conclusion is that only 37% of the registered electorate bothered to vote, meaning that we simply don’t know what the other 63% currently think. What is clear, however, is that, with just 37% of the voting age population to draw on, the Brexit Party’s alleged triumph is actually only an endorsement of its hard line on Europe from just 11.7% of the registered electorate.

As a lifelong opponent of the heartless modern version of the Conservative Party created by Margaret Thatcher, and maintained since 2010 by David Cameron and George Osborne, and, since the summer of 2016 by Theresa May, It was reassuring to see the Tories suffer their worst elections results ever. However, their losses (down to 4 seats, from 19 in 2014, and with just 9.1% of the vote, down from 23.9%), plus Labour’s woes (down to ten seats from 20, and with 14.1% of the vote, down from 25.4% in 2014) won’t be replicated in a General Election, in which our antiquated, profoundly unfair first-past-the-post system — as opposed to the European elections’ much more commendable system of proportional representation — favours the two main parties.

That said, it’s not unthinkable in the current circumstances that the Lib Dems and the Brexit Party could divide the vote sufficiently to destabilise the tired duopoly that has dominated British politics throughout my lifetime, perhaps leading a situation where, finally, we grow up sufficiently to embrace proportional representation as the only fair way of electing our MPs.

But that’s still a long way off. Now, following Theresa May’s imminent departure (amidst the tears she shed for herself, having never apparently cried about anyone else’s misfortune), the Tories are engaged in another leadership battle, bitterly divided between insane ‘no deal’ Brexiteers, led by the truly despicable and unprincipled Boris Johnson, and those more sensibly seeking to avoid economic suicide.

If there is any poetic justice in this often strangely backward country of ours, the clash between the ‘no deal’ Brexiteers (who, it seems, all stand to make colossal amounts of money from our enforced return to the worst aspects of Victorian Britain) and the centrists still trying to fulfil the unfulfillable mission of leaving the EU without it involving considerable damage to the economy will actually succeed only in destroying the Conservative Party as a major political force.

The Labour Party, meanwhile, seems finally to be coming off the fence to endorse a second referendum, finally overcoming the reluctance of the leadership (including Jeremy Corbyn) to alienate Labour Leave voters, and, in Corbyn’s case, I think, to continue to cling to a fanciful notion of a socialist Britain somehow freed, rather than crippled, by leaving the EU, a tired old fantasy that somehow ignores how globally inter-connected we all are these days, and that, while there are both good and bad aspects of that, the movement of goods, people and ideas across borders delivers more than it destroys.

Nevertheless, although it now looks probable that there has been a swing from Leave to Remain in the 72% of the population who voted in the EU referendum, when 52% voted Leave, and 48% voted Remain, the wild card is still the 28% of the population who didn’t vote in the referendum — and who are mostly included in the 63% of the registered electorate who didn’t vote on Thursday. In a second referendum, it remains possible that our rabid tabloid media, plus whatever dark forces are funding Nigel Farage, will prevail again.

One way out of that disastrous future would be for a second referendum to require our departure from the EU to be endorsed by a two-thirds majority, as is normal in referendums dealing with major constitutional change, and as should have happened in 2016, when, instead, David Cameron’s idiotic hubris set this whole train wreck in operation.

However, another way would be for MPs — the sovereign power in the UK that Leavers apparently wanted to reinstate — to come together to scrap Brexit via legislation explaining that it is impossible to implement without fundamentally destroying our economy, and then calling a general election, secure in the knowledge that they have put their principles before party politics or their own self-preservation.

In conclusion, I’d also like to dwell briefly on the two aspects of the European elections that cheered me the most. The first is the success of the Green Party, whose vote rose to 12.1% of the total, up from 7.9% in 2014. The Greens now have seven MEPs, up from three, and while many centrist Remainers voted for the Lib Dems, those more left-leaning and radical obviously voted Green, not just because of their support for remaining in the EU, but also because they’re the only party committed to tackling the true crisis of modern civilisation: not the delusional nostalgia and isolationism of the Brexiteers, but the exact opposite — the forward-looking, global, youthful advocacy for immediate and profound system change as the only way of averting the worst effects of an ongoing man-made global environmental catastrophe, whose urgency has, of course, recently been highlighted to great effect by Extinction Rebellion, by Greta Thunberg and the school strikes for climate — and even by Sir David Attenborough in his powerful documentary, ‘Climate Change: The Facts.’

I’d also like to big up London, my home, the only area in England where the Brexit Party didn’t come first (they came third, after the Lib Dems and Labour), and where the Tories were wiped out, losing their two seats and dropping to 7.9% of the vote, down from 22.5% in 2014.

If, despite all of the above, Brexit really does go ahead, London should surely be as entitled as Scotland to demand independence from a country hell-bent on re-making itself as a permanent “hostile environment” for foreigners, run largely by the US, China and the Gulf countries who already own so much of our land and our businesses, with public school boys acting as well-paid pimps, and with poverty levels that would make 19th century social reformers turn in their graves.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 24, 2019

Deptford’s Tidemill Campaign and the Dawning Environmental Rebellion Against the Dirty Housing ‘Regeneration’ Industry

Save Reginald Save Tidemill campaigners photographed in the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford in November 2018 (Photo: Andy Worthington).

Save Reginald Save Tidemill campaigners photographed in the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford in November 2018 (Photo: Andy Worthington).Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Yesterday, May 23, 2019, another phase in the ten-year struggle by the local community in Deptford to prevent environmental destruction, social cleansing, and the creation of new and inappropriate housing came to an end when campaigners with the Save Reginald Save Tidemill campaign withdrew from a protest camp — which had existed for the last seven months — on the green next to the contested site of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden.

However, while Lewisham Council and Peabody, the main proposed developer of the site, will be tempted to see this withdrawal as some sort of victory, they should pay attention to the fact that campaigners have also resolutely pledged to continue to resist the plans to build new homes on the site of the garden, and to demolish Reginald House, a block of 16 structurally sound council flats next door.

Moreover, the council and Peabody also need be aware that the contested Tidemill site is part of a much bigger picture — involving a critical awareness of environmental destruction and of the need for major systemic change to mitigate the worst effects of an already unfolding global environmental crisis — that has generated considerable awareness and support both globally and locally in recent months via the direct action embraced by the campaigning group Extinction Rebellion and the school strikes inspired by the 16-year old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg.

In addition, the entire model of the housing and ‘regeneration’ industry is under greater scrutiny than ever before, as activists from all walks of life recognise that destroying trees and green spaces, and endorsing a building industry that is, fundamentally, environmentally blind, is no longer acceptable.