Andy Worthington's Blog, page 103

January 24, 2015

Progress Towards Closing Guantánamo, As Periodic Review Boards Resume with the Case of a Seriously Ill Egyptian

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

The last three months have been a period of commendable progress at Guantánamo, as 27 prisoners have been released, reducing the prison’s population to just 122 men. On December 30, two Tunisians and three Yemenis were given new homes in Kazakhstan, and on January 14 five more Yemenis were given new homes — four in Oman, in the Gulf, and one in Estonia. All of these men had long been approved for release, having had their cases reviewed in 2009 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, which issued its final report in January 2010.

Obstacles raised by Congress — and the president’s unwillingness to spend political capital overcoming those obstacles — had led to these men being held for so long after the task force unanimously approved them for release, as well as a particular fear throughout the US establishment of repatriating Yemenis, because of unrest in their home country.

Two years ago, 86 of the men still held had been approved for release by the task force but were still held. That number is now down to 50, of whom 43 are Yemenis, and just seven are from other nations, including Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison.

Four more men have had their releases approved in the last year by Periodic Review Boards, another high-level, inter-agency process established in 2013 to review the cases of the majority of the men not cleared for release, to establish whether or not they are still regarding as constituting a threat.

Of the 68 men not approved for release, only ten are facing — or have faced — military commission trials at Guantánamo. Of the 58 others, 23 were recommended for prosecution by the task force, until the appeals court in Washington D.C. began dismissing the handful of convictions secured in the military commissions’ contentious history, on the basis that they were for war crimes that were not recognized internationally, and had been invented by Congress.

35 others were recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, on the basis that they were regarded as “too dangerous to release,” but insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial. This latter category ought to trouble anyone with respect for the law, because if there isn’t enough evidence to put someone on trial, then it’s not evidence — and in the case of the Guantánamo prisoners, this is because prisoners were routinely subjected to torture or other forms of abuse, or were bribed with the promise of comfort items, or because they simply grew exhausted by the pointless non-stop questioning, and began to tell their interrogators whatever they wanted to hear. The information obtained from the prisoners is, to be blunt, worthless to a shocking degree.

Here at “Close Guantánamo,” we are heartened to hear that the Periodic Reviews have resumed, after the nine prisoner reviews last year, which resulted in six of the men being recommended for release, and two being freed. The other four are Yemenis, who join their compatriots in the queue of Yemenis awaiting release. The last Yemeni to be cleared, Abdel Malik Ahmed Abdel Wahab Al-Rahabi (ISN 037), was recommended for ongoing detention in March 2014 after his PRB, but was approved for release in November after a second PRB.

The first review of the year took place on January 22, and was the first for any of the 23 prisoners who had initially been recommended for prosecution, but had been downgraded after the near-total collapse in the legitimacy of the military commissions.

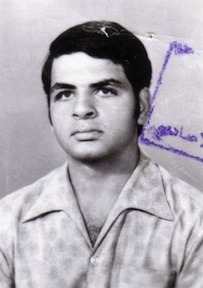

The story of Tariq al-Sawah

The prisoner in question, Tariq Mahmoud Ahmed al-Sawah (ISN 535), is known to seasoned Guantánamo watchers. An explosives expert in Afghanistan — possibly with al-Qaeda connections, although he has always denied it — he became disillusioned with his former life and has cooperated extensively with the authorities in Guantánamo. He is also seriously ill.

The prisoner in question, Tariq Mahmoud Ahmed al-Sawah (ISN 535), is known to seasoned Guantánamo watchers. An explosives expert in Afghanistan — possibly with al-Qaeda connections, although he has always denied it — he became disillusioned with his former life and has cooperated extensively with the authorities in Guantánamo. He is also seriously ill.

As the Associated Press described it in October 2013, he is “in terrible shape after 11 [now nearly 13] years as a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, a fact even the US military does not dispute.” At the time he was 55 years old, and his weight “has nearly doubled” during his long imprisonment, “reaching more than 420 pounds at one point, and his health has deteriorated as a result, both his lawyers and government officials concede.”

His lawyers — and a doctor who has examined him — paint what the AP described as “a dire picture” of “a morbidly obese man with diabetes and a range of other serious ailments,” who “is short of breath, barely able to walk 10 feet, unable to stay awake in meetings and faces the possibility of not making it out of prison alive.”

As I also explained in that article, the AP noted that al-Sawah had high-level support for his release, having “received letters of recommendation from three former Guantánamo commanders.” One, Rear Adm. David Thomas, recommended his release in his classified military file (his Detainee Assessment Brief) in September 2008, which was released by WikiLeaks in 2011, and only later contradicted by President Obama’s task force. In that file, al-Sawah’s health issues were also prominent. It was noted that he was “closely watched for significant and chronic problems” that included high cholesterol, diabetes and liver disease.

There was also a letter from an unnamed official who spent several hours a week with al-Sawah over the course of 18 months, who noted that he had been “friendly and cooperative” with US personnel, and stated, “Frankly, I felt Tarek [Tariq] was a good man on the other side who, in a different world, different time, different place, could easily be accepted as a friend or neighbour.”

Just as important is the fact that, back in March 2010, in an important article for the Washington Post, Peter Finn reported that al-Sawah and another prisoner, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a Mauritanian whose heart-rending memoir, written in Guantánamo, has just been published as a book, even though he is still held in the prison, “had become two of the most significant informants” in Guantánamo. As a result, they were “housed in a little fenced-in compound at the military prison, where they live[d] a life of relative privilege — gardening, writing and painting — separated from other detainees in a cocoon designed to reward and protect.”

What was particularly shocking about this was the refusal of the authorities to reward the men for their extensive cooperation by releasing them. As Finn noted, “Some military officials believe the United States should let them go — and put them into a witness protection program, in conjunction with allies, in a bid to cultivate more informants,” an eminently sensible suggestion that was endorsed by W. Patrick Lang, a retired senior military intelligence officer. “I don’t see why they aren’t given asylum,” Lang said. “If we don’t do this right, it will be that much harder to get other people to cooperate with us. And if I was still in the business, I’d want it known we protected them. It’s good advertising.” Finn also noted that a military official at Guantánamo at the time of his article had “suggested that that argument was fair,” although he stated that it was “a hard-sell argument around here.”

It is to be hoped that his release will not be such a hard-sell now. His detainee profile, for his PRB, stated that he “met numerous senior terrorist leaders, but there are no indications he held a leadership position,” adding that while he “openly admits to having taken part in terrorism, there are no indications that he is interested in reengaging in extremist activity. He has told interrogators that he hopes to reunite with family members-some of whom live in Egypt, Bosnia, and the US.” Those drafting the profile added that there were “no indications that [al-Sawah] is in communication with extremists outside of Guantánamo,” and also explained that, if he “were repatriated to Egypt, he probably would seek to reside temporarily with family members while pursuing opportunities to resettle elsewhere,” which may be optimistic given his previous history, and it may be that, if approved for release, he will need to be resettled in a third country.

We will be watching the progress of the PRBs closely, hoping that President Obama can release all the prisoners approved for release, and that the review boards will also approve the release many of those who come before them, and who, we are willing to demonstrate through an analysis of the so-called evidence, are not, and have never been “too dangerous to release.”

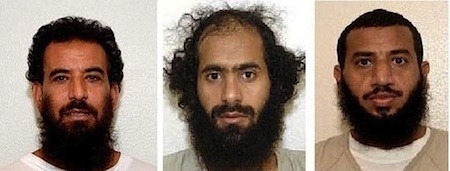

Note: Five more PRBs are forthcoming. Saeed Ahmed Mohammed Abdullah Sarem Jarabh (ISN 235), a Yemeni, has his hearing on January 27, and Khalid Ahmed Qasim (ISN 242), another Yemeni, follows on February 4. The three others were notified of their forthcoming PRBs on January 13. They are Mashur Abdullah Muqbil Ahmed Al-Sabri (ISN 324), a Yemeni, Abdul Shalabi (ISN 042), another Yemeni (and a long-term hunger striker), and Omar Khalif Mohammed Abu Baker Mahjour Umar (ISN 695), aka Omar Mohammed Khalifh, a Libyan whose habeas corpus petition was turned down in 2010.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

January 22, 2015

Photos and Report: Occupying Dick Cheney’s House and Protesting About Guantánamo, Torture and Drones Outside CIA HQ

Click here to see the whole of my photo set on Flickr.

On January 10, 2015, during my US tour to call for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay on and around the 13th anniversary of its opening (on January 11), I joined activists with Code Pink and Witness Against Torture for a day of action in Virginia, outside Washington D.C.

I was staying with Code Pink coordinator Joan Stallard, along with Debra Sweet, the national director of the World Can’t Wait, who organized my tour (for the fifth January in succession). Debra and I had driven from New York the day before, where I had been since Tuesday evening (January 6), and where I had been staying with my old friend The Talking Dog in Brooklyn. I indulged in some socializing at a Center for Constitutional Rights event on January 7, visited a high school and spoke to some students with Debra, and spoke at another event on January 8, with two Guantánamo lawyers, Ramzi Kassem and Omar Farah of CCR. I described We Stand With Shaker, the campaign to free Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and we also watched the promotional video, featuring my “Song for Shaker Aamer,” as well as CCR’s film about Fahd Ghazy, one of their Yemeni clients. A video of my talk is available here.

I also had the opportunity to walk the streets of Manhattan — and to cross the Brooklyn Bridge on foot — in spite of the seriously cold weather, but just as I was getting used to being in New York City, Washington D.C. beckoned. On the evening of January 9, after a drive full of animated chatter about politics and the state of the world, we (anti-drone activist Nick, our driver, film-maker/photographer Kat Watters, Debra and I) stopped by at the church where Witness Against Torture activists were staying — and fasting — and I gave a short and hopefully constructive speech and played my song for Shaker on an acoustic guitar.

The next thing I knew, it was Saturday morning and although we had missed the first action of the day — a protest outside the house of CIA director John Brennan — I was watching as an activist dressed as Dick Cheney and calling for the arrest of Dick Cheney was — briefly — arrested outside Cheney’s house in McLean, a stone’s throw from CIA headquarters. The ironies of this were lost on the police, who were humiliated because they had been blocking the wrong road and had failed to stop the activists not only getting to Cheney’s house, but occupying his lawn when it turned out that his gate was unlocked. However, it made for a great protest, and we were all relieved when the not-real Dick Cheney (Tighe Barry of Code Pink) and another arrested activist (83-year old Eve Tetaz) were released after a short time in police custody.

We then made our way to one of the entrances to CIA headquarters, where I had been involved in a protest two years before, and where I spoke again, although I’m not sure if it was filmed. It was great to hang out with so many great activists, and I hope you enjoy the photos, and share them if you do. In the near future, I’ll be posting more photos, from the 13th anniversary protest in Washington D.C., and you can also see photos I took of activists holding “We Stand With Shaker” placards here (as part of a new campaign calling for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, which I launched in November with fellow activist Joanne MacInnes).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

January 20, 2015

Who Are the Five Yemenis Released from Guantánamo and Given New Homes in Oman and Estonia?

Last week, on January 14, the population of Guantánamo was reduced again as five more men were released, leaving 122 men still held, 54 of whom have been approved for release. The released men are all Yemenis, and four were sent to Oman, in the Gulf, and one to Estonia. The releases reinforce President Obama’s commitment to closing Guantánamo, and mark the third release of Yemenis since the president’s promise to resume releasing prisoners in May 2013, after nearly three years in which the release of prisoners had almost ground to a halt because of opposition in Congress and the president’s refusal to spend political capital overdoing that opposition, and the specific lifting of a ban on releasing Yemenis that he had imposed after a failed airline bomb plot in December 2009 that had been hatched in Yemen.

Last week, on January 14, the population of Guantánamo was reduced again as five more men were released, leaving 122 men still held, 54 of whom have been approved for release. The released men are all Yemenis, and four were sent to Oman, in the Gulf, and one to Estonia. The releases reinforce President Obama’s commitment to closing Guantánamo, and mark the third release of Yemenis since the president’s promise to resume releasing prisoners in May 2013, after nearly three years in which the release of prisoners had almost ground to a halt because of opposition in Congress and the president’s refusal to spend political capital overdoing that opposition, and the specific lifting of a ban on releasing Yemenis that he had imposed after a failed airline bomb plot in December 2009 that had been hatched in Yemen.

Across the US establishment, there continues to be a refusal to countenance the repatriation of Yemenis, because of fears about the ongoing security problems in the country, and so third countries have had to be found — firstly, Georgia and Slovakia, then Kazakhstan, and now Estonia and Oman. Although Oman borders Yemen, Abdulwahab Alkebsi, an expert on Yemen at the Center for International Private Enterprise in Washington, D.C., described Oman to the Miami Herald as “one of the more stable countries in the Arab World with a vast desert between it and neighboring Yemen.” Socially, he said, “Oman will be a better place to reintegrate into life than Latin America or Europe,” with, as the Miami Herald put it, “a common language, stable economy, educational and business opportunities that provide a better quality of life than impoverished Yemen.”

The first of the four men released in Oman is Khadr al-Yafi (aka Al-Khadr Abdallah al-Yafi), ISN 34, who was 31 years old when he was seized crossing from Afghanistan to Pakistan with a group of other men. Al-Yafi had been a farmer in Yemen, and had served for two and a half years in the Yemeni army before traveling to Afghanistan. He said that after hearing a sermon, he “decided to return home and sell his sheep so that he could travel to Afghanistan to teach.”

The US claimed that he had been seen in various guest houses connected with military activity, which may have been true (although no evidence has ever been presented to prove categorically that being in a guest house confirmed military activity), and also made a much more far-fetched claim that he was a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden, like all the men captured with him, who were described as the “Dirty Thirty” (see my article, “Dangerous Revisionism Over Guantánamo” for FAIR in 2009, which discusses the “Dirty Thirty”).

The unreliability of this claim was confirmed when he was approved for release in his Detainee Assessment Brief (one of the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011), dated April 5, 2007. He was then approved for release again in 2009 by President Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force.

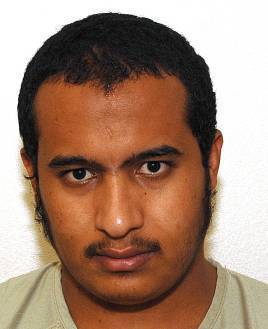

The second of the four men released in Oman is Abd al-Rahman Abdullah Abu Shabati (aka Abd al-Rahman Muhammad), ISN 224, who was just 19 years old when he was seized.

Shabati said in Guantánamo that he had wanted to teach in Afghanistan, but had ended up in a madrassa, where he had stayed for just ten days until the 9/11 attacks. After that, he said, the people at the madrassa sent him to a “known Taliban house” near Kabul, and from there he eventually made his way to the Pakistani border, where he was seized. Although the US authorities came up with an impressive list of documents seized in raids, on which his name and details were allegedly recorded, there is no way of knowing how accurate these records are, as many featured supposed “aliases” that were notoriously generic, and others appear to record the names of prisoners that were leaked to al-Qaeda sympathizers, who duly described them in online postings as al-Qaeda members. For his part, Shabati “denied that he received any weapons [training] during his one-month stay in Kabul.”

Like Khadr al-Yafi, Abd al-Rahman Shabati was approved for release in his Detainee Assessment Brief (one of the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011), in his case in a decision dated January 14, 2007. He was then approved for release again in 2009 by President Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force.

The third of the four men released in Oman is Fadil Husayn Salih Hintif, ISN 259, who appears to have been 20 years old when he was seized. As I explained in an article in 2010:

[He] told his tribunal at Guantánamo that he had spent many years working as a farmer on his family’s land, and had then moved to Sana’a to look for work. There he met a man at a mosque who asked him about “going to Afghanistan to help poor Afghans,” and he “felt this would be a chance to do something good in memory of his deceased father, so he thought it was a good idea.” He then apparently sold his car to raise funds for his trip, received some money from his brother and set off for Afghanistan. In Kabul, he “began living with an individual who previously taught the Koran in Afghanistan,” and when he asked him how he could help the Afghans, was told that “he could either work with the Afghani Red Crescent or he could help distribute food supplies.” Having decided to work for the Red Crescent, he said that he traveled with the instructor to Logar province, south of Kabul, but stopped his work after the US-led invasion began, when he was escorted to the Pakistani border. There, he said, he surrendered to the Pakistani police, who took him to a prison in Peshawar. He was then transferred to a larger prison in Kohat, and was eventually turned over to the Americans.

Throughout his whole story, Hintif maintained that he “did not receive any training in Afghanistan” and “did not fight in Afghanistan because he was not convinced of the causes that were being fought for.” He explained that he “felt that the groups there were fighting for power, and that there was no reason to fight a jihad.” Disturbingly, apart from vague allegations about the guest houses in which he stayed, the only allegations that the US authorities [had] been able to come up with [were] that his name was on a document “recovered from a safe house raid associated with al-Qaeda in Karachi, Pakistan” (which is not necessarily reliable, as it may not have been his name, but a kunya or alias that does not necessarily refer to him) and a much-derided claim that his Casio watch was the same model as one used in improvised explosive devices “in bombings linked to al-Qaeda and radical Islamic terrorist groups.”

Like Khadr al-Yafi and Abd al-Rahman Shabati, Fadil Hintif (whose habeas corpus petition was turned down by a federal court judge in 2011) was approved for release in his Detainee Assessment Brief (one of the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011), in his case in a decision dated January 9, 2007. He was then approved for release again in 2009 by President Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force.

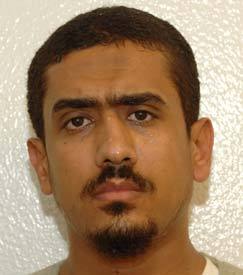

The last of the four men released in Oman is Mohammed al-Khatib (aka Muhammad Ahmad Salam), ISN 689, born in October 1980, who was just 21 years old when he was seized in a house raid in Faisalabad, Afghanistan, on March 28, 2002, the same day that another house raid led to the capture of Abu Zubaydah, the facilitator of a training camp that was not aligned with al-Qaeda, who was mistakenly regarded as al-Qaeda’s number 3, and subjected to horrendous torture (including 83 waterboarding sessions) as the first official subject of the CIA’s torture program.

The last of the four men released in Oman is Mohammed al-Khatib (aka Muhammad Ahmad Salam), ISN 689, born in October 1980, who was just 21 years old when he was seized in a house raid in Faisalabad, Afghanistan, on March 28, 2002, the same day that another house raid led to the capture of Abu Zubaydah, the facilitator of a training camp that was not aligned with al-Qaeda, who was mistakenly regarded as al-Qaeda’s number 3, and subjected to horrendous torture (including 83 waterboarding sessions) as the first official subject of the CIA’s torture program.

15 men, including al-Khatib, were seized in the raid, and they mostly claimed that they were students. Eight had been released prior to this latest batch of releases, two after having their habeas corpus petitions granted, and two in recent months (a Yemeni and a Palestinian). Another man, sadly, was one of the three prisoners who died at Guantánamo, in mysterious circumstances, in June 2006, reportedly by committing suicide, although that explanation has been seriously challenged in the years since (see the latest news on the alleged suicides here).

As I explained in an article in October 2010 describing the circumstances of the arrest of the 15 men:

In May 2009, Judge Gladys Kessler, ruling on the habeas corpus petition of one of the [men], Alla Ali Bin Ali Ahmed, who described himself as a student, savaged the government for drawing on the testimony of witnesses whose unreliability was acknowledged by the authorities, and for attempting to create a “mosaic” of intelligence that was thoroughly unconvincing, and she also made a point of stating, “It is likely, based on evidence in the record, that at least a majority of the [redacted] guests were indeed students, living at a guest house that was located close to a university.”

As I explained in another article in 2010:

[Al-Khatib], who was reportedly seen by “a senior al-Qaeda member” at al-Farouq [the main training camp in Afghanistan for recruits from the Gulf] actually presented a far more coherent narrative, which involved traveling to Pakistan to get treatment on his nose, and then meeting up with a missionary under whose guidance he traveled to Faisalabad to study the Koran, where he stayed for eight months until he was seized in the house raid. In his tribunal at Guantánamo, after explaining that a “generous person” paid for his trip, the following exchange took place, which demonstrated how wide the cultural gap was between the Americans and Muslims from the Gulf:

Tribunal Member: I don’t know your culture very well, but … in our culture people just don’t step up and say, “I’ll pay for the trip for you.”

Detainee: In our culture, in Islam, there is such a thing … Indeed, it is an obligation for any Muslim who is rich to pay for someone who is poor.

The fifth man freed last week, who was sent to Estonia, is Ahmed Abdul Qader (aka Akhmed — or Ahmed — Abdul Qadir Hussain, or Abdul Qader Ahmed Hussain), ISN 690, who was also seized in the Faisalabad house raid along with Mohammed al-Khatib. Born in November 1983, he had turned 18 just four months before his capture.

[Qader] said in Guantánamo that he went to Afghanistan “to help the needy and the poor,” and tried unsuccessfully to establish a charity organization. He admitted that he visited the “back line,” encouraged by friends connected to the Taliban, but insisted that he “never participated in any kind of military activities.” After leaving Afghanistan before the US-led invasion began, he said that he ended up in the house in Faisalabad, where he became friends with Fahmi Ahmed [ISN 688, still held]. “We shared the same vision and he has the same opinions,” Ahmed said of him, adding, “He used to use hashish with me,” whereas the other students in the house “were trying to inspire me to do the religious things, like look at my religion, because most of the students were studying the Koran and all things related to religious studies.”

Below I’m posting an article in the New Yorker written after the men’s release by Amy Davidson, focusing on the story of Ahmed Abdul Qadir Hussain (including reference to his habeas corpus petition in 2011, which was turned down by a federal court judge after the appeals court in Washington D.C. gutted habeas corpus of all meaning for the Guantánamo prisoners), and comparing it with the disgraceful pro-Guantánamo posturing of a handful of Republican senators, who used the murders in Paris to call for a ban on the release of prisoners from Guantánamo, even those approved for release five years ago.

Sent to Guantánamo as a Teen-Ager, and Now to Estonia

By Amy Davidson, New Yorker, January 15, 2015

When Akhmed Abdul Qadir Hussain was eighteen (or a little younger, by some accounts), in early 2002, he was arrested by the Pakistani police, who gave him to American forces, who sent him to Guantánamo Bay. When he was about twenty-five, in 2009, the Guantánamo Review Task Force cleared him for release. It had taken seven years, but, as a Pentagon press release put it, “this man was unanimously approved for transfer by the six departments and agencies comprising the task force.” But he remained in Guantánamo for more than five additional years. Finally, on Wednesday, the Obama Administration announced that it had put Hussain on a plane to Estonia. He is not Estonian; he was born in Yemen. But now, at the age of about thirty-one, he will presumably learn at least the rudiments of the Estonian language, maybe while taking in the architecture in Talinn’s old city and on the Baltic coast. Four other Guantánamo prisoners were sent to Oman; they were also Yemeni. Each of them had been held for a dozen years or more, and each had also been cleared for release five years earlier. Neither they nor Hussain had ever been charged with anything.

When Akhmed Abdul Qadir Hussain was eighteen (or a little younger, by some accounts), in early 2002, he was arrested by the Pakistani police, who gave him to American forces, who sent him to Guantánamo Bay. When he was about twenty-five, in 2009, the Guantánamo Review Task Force cleared him for release. It had taken seven years, but, as a Pentagon press release put it, “this man was unanimously approved for transfer by the six departments and agencies comprising the task force.” But he remained in Guantánamo for more than five additional years. Finally, on Wednesday, the Obama Administration announced that it had put Hussain on a plane to Estonia. He is not Estonian; he was born in Yemen. But now, at the age of about thirty-one, he will presumably learn at least the rudiments of the Estonian language, maybe while taking in the architecture in Talinn’s old city and on the Baltic coast. Four other Guantánamo prisoners were sent to Oman; they were also Yemeni. Each of them had been held for a dozen years or more, and each had also been cleared for release five years earlier. Neither they nor Hussain had ever been charged with anything.

Congress is informed before such releases, which might explain why, the day before the announcement, Republican Senators John McCain, Kelly Ayotte, and Lindsey Graham came out with a proposal for new Guantánamo legislation. It was not an effort to find a way to prevent teen-agers from being locked up for no good reason until they are in their thirties. Instead, it called for what would effectively be a moratorium on any transfers from Guantánamo. Under the proposal, no prisoner could be transferred to Yemen (although there are dozens of Yemenis who have been cleared for release) because Yemen, according to Ayotte, is “the Wild West.” And for the next two years, no prisoner who had received a medium-risk or high-risk designation could be released at all — never mind if nothing had ever been proved against him.

The medium-risk designation seems to be pretty easy to get; until his case was finally reviewed, Hussain was called that, on the ground that he had spent time at a guest house associated with the Taliban, where, the government argued, he had been “trained” (in what, exactly, isn’t really clear) and had access to a gun. In a 2008 assessment, he was also labelled as “a HIGH threat from a detention perspective,” because he had been “non-compliant and hostile to the guard force.” He hadn’t actually tried to attack anyone, but he had accumulated seventy-five disciplinary infractions, including “inappropriate use of bodily fluids,” with “the most recent occurring on 6 March 2008, when he refused to return a library book.”

Reading the paperwork, such as it is, that explains Hussain’s detention, one is struck by how little anyone seems to have considered that he was a teen-ager, and perhaps a minor, when he was put in a jumpsuit in a prison camp. But he would not have been the only juvenile — or even the youngest prisoner — at Guantánamo. The United States’s blindness about child prisoners is not confined to terrorism suspects; far too many underage suspects are sentenced and incarcerated as adults. It was only last week that New York City officials decided to stop putting prisoners under the age of twenty-one in solitary confinement at Rikers Island. (See Jennifer Gonnerman’s harrowing account of a childhood lost in that jail.) But not so many end up in Estonia.

This befuddlement seems to have extended to earlier reviews of Hussain’s case. When Judge Reggie B. Walton denied Hussain’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus, in 2011, he discounted Hussain’s account of what he had been doing in Pakistan and Afghanistan, in part because Hussain seemed suspiciously unrealistic about what kind of job he could get, clueless about the motives of the older men he was spending time with, aimless when it came to registering for school, and not in a hurry to go home and get married — this, again, when he was seventeen. (The blog Lawfare posted a link to the decision.) Hussain explained that he’d lingered in Lahore because when he looked for plane tickets home they’d seemed too expensive, with too many layovers, and he had wanted a cheaper, direct flight. The judge found this to be a “nonsensical” explanation, “given that the more layovers a traveler must experience to reach his or her final destination generally results in a less expensive ticket for the traveler.” Doesn’t everyone know that?

When the judges on the D.C. Circuit Court heard an appeal of Walton’s denial, two years later, they upheld it, although Judge Harry T. Edwards, in his concurrence, at least sounded frustrated by where the “vagaries” of Guantánamo jurisprudence had led. “Is it really surprising that a teenager, or someone recounting his teenage years, sounds unbelievable? What is a judge to make of this, especially here, where there is not one iota of evidence that [he] ‘planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such … persons’?” (Linda Greenhouse wrote about the opinion a few weeks ago, before news of Hussain’s transfer.) Edwards said that he was “disquieted.” Other relevant words might involve shame.

President Barack Obama’s first executive order, on January 22, 2009, called for the closing of Guantánamo. There are still a hundred and twenty-two prisoners there, fifty-four of whom have been cleared for release. Fewer than a dozen have any sort of prosecution pending against them. The cases that are in motion — some against dangerous, murderous people, such as Khalid Sheikh Mohammed — have been bungled and delayed, far more so than they would have been if they had been brought in, say, the Southern District of New York, where the World Trade Center stood (and is now standing again). After a period of paralysis, during which the Administration appeared to have more or less thrown up its hands, the President is trying again, one plane ticket to Uruguay, or to the Baltic states, at a time.

The Republicans have been pushing back, citing the recent attacks in Paris, and talking about recidivism — although recidivist, with the implication of a return to a life of crime, is a strange thing to call a person whom you’ve never charged with a crime in the first place. According to the Times, the White House has a theory that if it can get the number of prisoners in Guantánamo down to between sixty and eighty, “keeping it open would make no economic sense” — as if it makes any economic sense now, at three million dollars per year, per prisoner. Does the White House’s strategy for closing Guantánamo involve Congress acting rationally? It will need a better plan than that.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

See the following for articles about the 142 prisoners released from Guantánamo from June 2007 to January 2009 (out of the 532 released by President Bush), and the 110 prisoners released from February 2009 to December 2014 (by President Obama), whose stories are covered in more detail than is available anywhere else –- either in print or on the internet –- although many of them, of course, are also covered in The Guantánamo Files, and for the stories of the other 390 prisoners released by President Bush, see my archive of articles based on the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011: June 2007 –- 2 Tunisians, 4 Yemenis (here, here and here); July 2007 –- 16 Saudis; August 2007 –- 1 Bahraini, 5 Afghans; September 2007 –- 16 Saudis; September 2007 –- 1 Mauritanian; September 2007 –- 1 Libyan, 1 Yemeni, 6 Afghans; November 2007 –- 3 Jordanians, 8 Afghans; November 2007 –- 14 Saudis; December 2007 –- 2 Sudanese; December 2007 –- 13 Afghans (here and here); December 2007 –- 3 British residents; December 2007 –- 10 Saudis; May 2008 –- 3 Sudanese, 1 Moroccan, 5 Afghans (here, here and here); July 2008 –- 2 Algerians; July 2008 –- 1 Qatari, 1 United Arab Emirati, 1 Afghan; August 2008 –- 2 Algerians; September 2008 –- 1 Pakistani, 2 Afghans (here and here); September 2008 –- 1 Sudanese, 1 Algerian; November 2008 –- 1 Kazakh, 1 Somali, 1 Tajik; November 2008 –- 2 Algerians; November 2008 –- 1 Yemeni (Salim Hamdan) repatriated to serve out the last month of his sentence; December 2008 –- 3 Bosnian Algerians; January 2009 –- 1 Afghan, 1 Algerian, 4 Iraqis; February 2009 — 1 British resident (Binyam Mohamed); May 2009 —1 Bosnian Algerian (Lakhdar Boumediene); June 2009 — 1 Chadian (Mohammed El-Gharani), 4 Uighurs to Bermuda, 1 Iraqi, 3 Saudis (here and here); August 2009 — 1 Afghan (Mohamed Jawad), 2 Syrians to Portugal; September 2009 — 1 Yemeni, 2 Uzbeks to Ireland (here and here); October 2009 — 1 Kuwaiti, 1 prisoner of undisclosed nationality to Belgium; October 2009 — 6 Uighurs to Palau; November 2009 — 1 Bosnian Algerian to France, 1 unidentified Palestinian to Hungary, 2 Tunisians to Italian custody; December 2009 — 1 Kuwaiti (Fouad al-Rabiah); December 2009 — 2 Somalis, 4 Afghans, 6 Yemenis; January 2010 — 2 Algerians, 1 Uzbek to Switzerland, 1 Egyptian, 1 Azerbaijani and 1 Tunisian to Slovakia; February 2010 — 1 Egyptian, 1 Libyan, 1 Tunisian to Albania, 1 Palestinian to Spain; March 2010 — 1 Libyan, 2 unidentified prisoners to Georgia, 2 Uighurs to Switzerland; May 2010 — 1 Syrian to Bulgaria, 1 Yemeni to Spain; July 2010 — 1 Yemeni (Mohammed Hassan Odaini); July 2010 — 1 Algerian, 1 Syrian to Cape Verde, 1 Uzbek to Latvia, 1 unidentified Afghan to Spain; September 2010 — 1 Palestinian, 1 Syrian to Germany; January 2011 — 1 Algerian; April 2012 — 2 Uighurs to El Salvador; July 2012 — 1 Sudanese; September 2012 — 1 Canadian (Omar Khadr) to ongoing imprisonment in Canada; August 2013 — 2 Algerians; December 2013 — 2 Algerians, 2 Saudis, 2 Sudanese, 3 Uighurs to Slovakia; March 2014 — 1 Algerian (Ahmed Belbacha); May 2014 — 5 Afghans to Qatar (in a prisoner swap for US PoW Bowe Bergdahl); November 2014 — 1 Kuwaiti (Fawzi al-Odah); November 2014 — 3 Yemenis to Georgia, 1 Yemeni and 1 Tunisian to Slovakia, and 1 Saudi; December 2014 — 4 Syrians, a Palestinian and a Tunisian to Uruguay, 4 Afghans, 2 Tunisians and 3 Yemenis to Kazakhstan.

January 19, 2015

Radio, TV and Live Events: Andy Worthington Discusses Guantánamo and the Need to Close the Prison During His US Tour

I’m back from my US tour, recovering from jet lag and fatigue as a result of a punishing (if rewarding) Stateside schedule, in which, over an 11-day period, I visited New York, Washington D.C., Boston and other locations in Massachusetts, and Chicago as part of series of events to mark the 13th anniversary of the opening of the prison at Guantánamo, organized by Debra Sweet of World Can’t Wait, who accompanied me for the majority of the visit. I’ve already posted videos of me speaking outside the White House on the anniversary, and a video of an event at New America on January 12 at which I spoke along with the attorney Tom Wilner and Col. Morris Davis, the former chief prosecutor of the military commissions at Guantánamo, who is now an implacable critic of the “war on terror.”

I’m back from my US tour, recovering from jet lag and fatigue as a result of a punishing (if rewarding) Stateside schedule, in which, over an 11-day period, I visited New York, Washington D.C., Boston and other locations in Massachusetts, and Chicago as part of series of events to mark the 13th anniversary of the opening of the prison at Guantánamo, organized by Debra Sweet of World Can’t Wait, who accompanied me for the majority of the visit. I’ve already posted videos of me speaking outside the White House on the anniversary, and a video of an event at New America on January 12 at which I spoke along with the attorney Tom Wilner and Col. Morris Davis, the former chief prosecutor of the military commissions at Guantánamo, who is now an implacable critic of the “war on terror.”

Below, I’m posting links to three radio shows I did on January 14, when I was in Massachusetts (one of which was with a show in Chicago, and was broadcast the day after), and a TV interview I did that same day for a local news show, WWLP-22News. On that particularly busy day, I also spoke at two events, for which videos will shortly be available.

For my first interview, at 9am, I spoke to Bill Newman, a civil rights and criminal defense attorney and the director of the western Massachusetts office of the ACLU, who hosts a weekday radio talk show on WHMP in Northampton, Massachusetts. Bill also worked as co-counsel on behalf of a Guantánamo prisoner several years ago.

Bill and I had met at a dinner the evening before, arranged by Nancy Talanian of No More Guantánamos (who organized my events in Massachusetts), where other attendees included Buz Eisenberg, an attorney who has represented seven Guantánamo prisoners, all now released, and several members of Witness Against Torture, who had just returned from Washington D.C. It was great to meet Buz and Bill for the first time. We got on really well, and Buz was particularly lavish in his praise for my work, which was immensely gratifying.

Bill’s 50-minute show from January 14 is here, and our interview begins at the start of the show and ends at 34 minutes. It was a great pleasure to talk to him, and to have so much time to look in depth at the sad and enduring story of Guantánamo.

For my second interview, I spoke briefly to Paul Tuthill, the Bureau Chief of NPR affiliate WAMC/Northeast Public Radio, just prior to a talk I was giving at Western New England University School of Law. That seven-minute interview is here, and it was a pleasure to speak to Paul. A video of my subsequent talk should be available soon.

For my third interview, I spoke to Jerome McDonnell for his show, “Worldview,” on WBEZ 91.5 in Chicago, an NPR affiliate, for a widely-heard show in Chicago, which was broadcast on January 15, the day I arrived in Chicago with Debra Sweet for an event that also featured Candace Gorman, an independent lawyer who represents one prisoner still held, Abdul Razak Ali, and who represented another, Abdul Hamid al-Ghizzawi, released in 2010.

The 19-minute interview is here, where it is available via Soundcloud (or it can also be downloaded to iTunes). Scroll down to the section that begins, “Prisoners transferred from Guantánamo as lawmakers call for a moratorium.”

Jerome was a well-informed host, and it was a great pleasure to speak to him for the first time (and I hope we’ll speak again sometime). We discussed Guantánamo past, present and future and, about eleven and a half minutes in, Jerome asked me about We Stand With Shaker and Shaker Aamer’s case, and played out the show with the “Song for Shaker Aamer” that I wrote and played with my band The Four Fathers as the campaign song (see the video here).

This is how Jerome described the show:

This week the Obama administration moved five prisoners out of the Guantánamo Bay detention center, sending inmates to Oman and Estonia. In the aftermath of the terror attacks in France, a group of Republican lawmakers has proposed legislation that would slow the release of prisoners from Guantánamo. The new legislation would, among other things, prohibit the transfer of any detainees to Yemen for the next two years. We’ll talk about the proposed legislation with Andy Worthington, an investigative journalist and author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign.

On the evening of January 14, I spoke to a reporter/cameraman for WWLP-22News, for a broadcast under the heading, “British journalist speaks out against Guantánamo Bay.” That news feature is available here (it’s just one minute long), and the accompanying article quoted from my talk:

Worthington has been reporting on the people at Guantánamo for nine years, and wants the prison closed. He said the detainees were described as the “worst of the worst,” but he said that’s not really the case, “Only a very small number of them, you know, a few dozen, have ever been accused of serious involvement in terrorism. So the rest of the men are not this huge threat. And holding people without charge or trial is fundamentally un-American, and an indecent thing to do.”

I’m also posting below a video of the first big event I did in the US, at a church in New York on the evening of January 8, with two Guantánamo lawyers, Ramzi Kassem of City University New York (CUNY), who is one of Shaker Aamer’s lawyers, and Omar Farah of the Center for Constitutional Rights, who represents the Yemeni prisoner Fahd Ghazy (see CCR’s video here), and Debra Sweet. The audio is rather echoey, but I hope it captures something of the essential humanity of the evening, as I ran through the story of Guantánamo, and also spoke about We Stand With Shaker (and the campaign video was shown), and Ramzi and Omar spoke eloquently about their clients’ ongoing ordeal. Thanks to Cat Watters for the recording.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

January 17, 2015

Video: At New America, Andy Worthington, Tom Wilner and Col. Morris Davis Discuss the Closure of Guantánamo and the CIA Torture Report

At lunchtime on Monday January 12, the day after the 13th anniversary of the opening of the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (when I was speaking outside the White House), I took part in “Leaving the Dark Side? Emptying Guantánamo and the CIA Torture Report,” a panel discussion at New America.

At lunchtime on Monday January 12, the day after the 13th anniversary of the opening of the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (when I was speaking outside the White House), I took part in “Leaving the Dark Side? Emptying Guantánamo and the CIA Torture Report,” a panel discussion at New America.

With me at New America (formerly the New America Foundation) was Tom Wilner, who represented the Guantánamo prisoners before the Supreme Court in their habeas corpus cases in 2004 and 2008, and with whom I co-founded the Close Guantánamo campaign in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, and Col. Morris Davis, the former chief prosecutor of the military commissions at Guantánamo, who resigned in 2007, in protest at the use of torture, and has since become an outspoken critic of the prison and the “war on terror.”

The moderator was journalist and author Peter Bergen, the Director of the International Security, Future of War, and Fellows Programs at New America, who I have known since the early 1890s, when we were both at Oxford together.

The video is below, via YouTube. It was a lively discussion, and if you have the time to spare, I hope you watch it and share it if you find it useful.

We all spoke about the progress made in recent years in releasing prisoners, since the prison-wide hunger strike two years ago, and President Obama’s response to international criticism of his inaction — his promise, in May 2013, to resume releasing prisoners. Since that promise, 44 men have been released, compared to just five in the preceding two and a half years, when Congress raised legislative obstacles to the release of prisoners, and the president was unwilling to spend political capital overcoming them.

This is significant progress. Just 122 men are now held, and 54 of those men have been cleared for release — most for at least five years. I spoke about how these men must be released, and my hope that, of the 68 others, more will be released through the Periodic Review Board process, which so far has approved six men for release after hearing nine cases. The PRBs began just over a year ago to review the cases of the men neither cleared for release nor facing trials (this latter group numbering only about ten men).

We also spoke about the CIA torture report, about the need for accountability, about the broken military commission trial system, about Shaker Aamer (and the We Stand With Shaker campaign), and about the thorny issue of what should happen to enable President Obama to close Guantánamo for good. This will mean having to bring some prisoners to the US mainland — for some to face trials, and some to be imprisoned in a new context, which, Tom and I believe, will be temporary, as they will successfully be able to mount legal challenges, on the basis that indefinitely imprisoning people without charge or trial on the US mainland has no precedent and is fundamentally unconstitutional and in violation of the laws on which the US prides itself.

We acknowledge, however, that this is contentious, because of dark forces who are enthusiastic about introducing the indefinite detention of people without charge or trial on the US mainland, and we hope that it is something that will be discussed as widely and openly as possible the months to come, as all of us who care about the need to close Guantánamo engage with what that might actually mean, now that it is finally something we can glimpse as a possibility.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

January 14, 2015

Video: Andy Worthington Calls for the Closure of Guantánamo Outside the White House on January 11, 2015

January 11, 2015 was the 13th anniversary of the opening of the Bush administration’s “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo, and I traveled to the US to take part in protests in Washington D.C. on the anniversary, as well as in other locations in the US, as I have done since January 2011.

January 11, 2015 was the 13th anniversary of the opening of the Bush administration’s “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo, and I traveled to the US to take part in protests in Washington D.C. on the anniversary, as well as in other locations in the US, as I have done since January 2011.

I’m currently nearing the end of the tour, in Massachusetts, with a final date tomorrow in Chicago, but in the meantime I’m delighted to make available, via Witness Against Torture (and YouTube) the video of the rousing speech I gave outside the White House on January 11.

I spoke about We Stand With Shaker, the campaign I launched with activist Joanne MacInnes in November, calling for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and I also spoke about the 126 other men, calling for their release unless they are going to be tried — an outcome that only applies to around ten of the men still held. [Click on the photo to enlarge it].

The video is below. If you like it, please feel free to share it!

For all the videos of speakers and performers from January 11, please visit this Witness Against Torture page, where there are videos of all the speakers outside the White House (and Luke Nephew of the Peace Poets), as well as videos of performers at our final destination — after we’d marched to the Justice Department — an open area above the Washington D.C. Central Holding Cells where Shahid Buttar of the Bill of Rights Defense Committee performed “Welcome to the Terrordrome,” his excellent rap about the “war on terror.”

The video of Shahid is below:

I also want to mention “From Ferguson to Guantánamo,” the powerful event that took place at Witness Against Torture’s temporary HQ in Washington D.C. on the Saturday night, when a panel discussed endemic racism, the police’s impunity in killing black men, the bloated, racist and hideously punitive domestic prison system, the horrors of solitary confinement (in US prisons) and the horrors of Guantánamo. Those videos are available here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

January 13, 2015

Gitmo Clock Marks 600 Days Since President Obama’s Promise to Resume Releasing Prisoners from Guantánamo; 59 Cleared Prisoners Remain

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Remember President Obama’s promise to close Guantánamo within a year, which he made on his second day in office in January 2009?

So do we, and on Sunday, at the rally outside the White House, on the 13th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, we remembered that promise again, almost six years since it was made.

For many years now, these anniversaries have been cheerless occasions, as Congress sought to prevent the release of prisoners through the imposition of cynical and onerous legislation, and the president largely complied.

Then, almost two years ago, the prisoners took matters into their own hands. In despair at ever being released or being given justice, they embarked on a prison-wide hunger strike, which attracted so much criticism of the Obama administration’s inaction, both domestically and internationally, that President Obama promised, in a major speech on national security issues on May 23, 2013, to resume releasing prisoners from Guantánamo, after a period of nearly three years in which just five men had been released.

At the time of President Obama’s speech, 86 of the remaining 166 prisoners had been cleared for release by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that the president had established shortly after taking office to review the cases of all the men he had inherited from George W. Bush, and in light of the promise, here at “Close Guantánamo,” we established the Gitmo Clock to record how long it was since the promise and how many prisoners had been released — and yesterday the Gitmo Clock marked 600 days since President Obama’s fine words.

By the anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo last January, eleven men had been freed, which provided grounds for cautious optimism, but in the year since 28 more men have been released, bringing the total number of men released since the promise to 39.

Outside the White House on Sunday, we and other groups largely celebrated this progress, although we also noted that much remains to be done. Of the 127 men still held, 59 have been approved for release — 55 in 2009 by the Guantánamo Review Task Force, and four in the last year by a newly established review process, the Periodic Review Boards, established to look at the cases of everyone not cleared for release.

These men — who include Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and 52 Yemenis — must be released as swiftly as possible if the very real progress towards the closure of Guantánamo is to be maintained. This will not be easy, because of the entire US establishment’s refusal to repatriate Yemenis, a refusal based on fears about the security situation in their home country, which necessitates the finding of third countries prepared to offer the men new homes.

And when these men are freed, so too should be the majority of the other 68 men. Just ten are facing trials, but the rest were designated as too dangerous to release by the task force, even though its members — and President Obama, who endorsed their findings — conceded that there was insufficient evidence to put any of these men on trial.

That, of course, means that it is not evidence at all, but a collection of dubious information — multiple layers of hearsay, for example, produced by the prisoners themselves or their fellow prisoners, under torture or other forms of abuse, or through bribery or exhaustion. It is fundamentally unreliable, but the administration — or its representatives in the Periodic Review Boards — will have to accept this to enable these men also to be released.

While we wait to see whether this will happen — or perhaps how quickly or slowly it will happen — the Gitmo Clock remains a useful tool to keep track of developments — or, the worst case scenario, the lack of them. We hope that you find it useful, and that, if you haven’t done so already, you will visit it, like it, share it and tweet it.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, the director of “We Stand With Shaker,” calling for the immediate release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

January 11, 2015

As Guantánamo’s 14th Year of Operations Begins, This Must Be the Year It Closes

As the prison at Guantánamo Bay begins its 14th year of operations, I am in the US for a short tour calling for the prison’s closure — and, specifically, in Washington D.C. for a protest outside the White House on the actual anniversary of the prison’s opening — January 11.

As the prison at Guantánamo Bay begins its 14th year of operations, I am in the US for a short tour calling for the prison’s closure — and, specifically, in Washington D.C. for a protest outside the White House on the actual anniversary of the prison’s opening — January 11.

With 28 men freed in the last year, and just 127 men still held, there are reasons for cautious optimism that the end is now in sight for the prison, a reviled symbol of the Bush administration’s post-9/11 overreach and disdain for the law, and of President Obama’s difficulty in placing principles above political expediency.

Two good reviews of where we stand on Guantánamo’s 13th anniversary were published last week in the New York Times. In the first, “The Path to Closing Guantánamo,” Cliff Sloan, who has just resigned as the State Department’s envoy for closing Guantánamo (a role he has held since 2013), praised the progress made in the last 18 months — with 39 prisoners released, compared to four in the previous two years, when Congressional obstruction was at its most potent, and President Obama’s political will at its weakest.

In addition, as Cliff Sloan noted, “We also worked with Congress to remove unnecessary obstacles to foreign transfers,” and “began an administrative process to review the status of detainees not yet approved for transfer or formally charged with crimes” — the Periodic Review Boards, which have, to date, reviewed the cases of nine prisoners not already approved for release by a task force President Obama established in 2009, and recommended six for release.

As Cliff Sloan also noted, 59 of the 127 men still held have been “approved for transfer,” and as he proceeded to explain:

This means that six agencies — the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice and State, as well as the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the director of national intelligence — have unanimously approved the person for release based on everything known about the individual and the risk he presents. For most of those approved, this rigorous decision was made half a decade ago. Almost 90 percent of those approved are from Yemen, where the security situation is perilous. They are not “the worst of the worst,” but rather people with the worst luck. (We recently resettled several Yemenis in other countries, the first time any Yemeni had been transferred from Guantánamo in more than four years.)

Looking to the future, Cliff Sloan also noted that, although there has been “great progress” towards closing Guantánamo, it “will take intense and sustained action to finish the job.” As he explained, “The government must continue and accelerate the transfers of those approved for release. Administrative review of those not approved for transfer must be expedited.” Crucially, he added, “The absolute and irrational ban on transfers to the United States for any purpose, including detention and prosecution, must be changed as the population is reduced to a small core of detainees who cannot safely be transferred overseas.”

As Cliff Sloan also explained:

The reasons for closing Guantánamo are more compelling than ever. As a high-ranking security official from one of our staunchest allies on counterterrorism (not from Europe) once told me, “The greatest single action the United States can take to fight terrorism is to close Guantánamo.” I have seen firsthand the way in which Guantánamo frays and damages vitally important security relationships with countries around the world. The eye-popping cost — around $3 million per detainee last year, compared with roughly $75,000 at a “supermax” prison in the United States — drains vital resources.

Cliff Sloan’s op-ed ended with an important statement: “Imprisoning men without charges for this long — many of whom have been approved for transfer for almost half the period of their incarceration — is not in line with the country we aspire to be,” which is certainly the opinion of all Americans who respect the rule of law above the fearmongering that has eaten away at the country’s values since 9/11.

In another New York Times article last week, “Obama Nears Goal for Guantánamo With Faster Pace of Releases,” Helene Cooper looked in further detail at what might happen in the months to come. Firstly, she noted, the Pentagon is “ready to release two more groups of prisoners in the next two weeks,” although officials “will not provide a specific number.”

She added that President Obama’s goal, before leaving office, is “to deplete the Guantánamo prison to the point where it houses 60 to 80 people and keeping it open no longer makes economic sense.”

Officials explained that the president expects that Ashton B. Carter, nominated to be the next defense secretary, will “move more aggressively on emptying Guantánamo” than Chuck Hagel, whose caution evidently frustrated the White House, and ultimately led to his resignation. Carter’s colleagues told the Times that he is attuned to President Obama’s “desire to be part of the last chapter of the Guantánamo prison.”

Officials also told the Times that they “hope to keep up the current pace,” although they acknowledged that, “after the planned two groups of transfers, the releases may slow down,” because officials at the Pentagon and the State Department have to find countries prepared to take in the Yemenis approved for release, who make up 52 of the 59 men approved for release, in the absence of any confidence that the security situation in Yemen is sufficiently secure to allow any prisoners to be repatriated.

Ian Moss, the State Department’s spokesman for Guantánamo issues, said, “I can tell you that in the world of Gitmo transfers and our conversations with foreign governments, momentum matters.” He added, “We are aggressively reaching out to a wide variety of countries. This language was echoed by Paul Lewis, the Pentagon’s special envoy for the closure of Guantánamo, who said that “the Defense Department continues to aggressively pursue the transfer” of low-level prisoners who have been declared eligible for release. He added, “we take our obligation to assess the potential threat of detainees seriously prior to transfers,” but he also stated that in 2015 there could be “an increase of detainees eligible to transfer” — presumably through the Periodic Review Board process.

All decent people can only hope that, as 2015 — and the 14th year of Guantánamo’s operations — unfolds, the 59 men approved for release — including Shaker Aamer, the last British resident and the focus of my most recent campaign, We Stand With Shaker — will be freed, and serious efforts made to approve others for release through the Periodic Review Boards (because few of the 68 others genuinely pose any kind of threat, and only ten are facing trials), and to persuade Congress that the remaining prisoners must be transferred to the US mainland so that Guantánamo can be closed for good.