Gordon Grice's Blog, page 6

April 7, 2022

Grice on Grass, Bison, and Massacres

The peculiarities of bison hair, Custer's other massacre, hope for life on Earth, and more. Catch me chatting with the Oklahoma Today crew on this podcast.

March 2, 2022

Grasslands: "Out of Hopeful Green Stuff Woven"

My latest essay for Oklahoma Today, “Out of Hopeful Green Stuff Woven,” mixes history and ecology. If you’re the kind with cash in your pocket, help the magazine out by ordering a copy or a subscription. If you’re the other kind, which most of us are these days, wait a year or two and the piece will come up in a free archive. I’ll probably mention it here when that happens, unless I’m disorganized.

Meanwhile, I have these other recent essays you can read free:

Midwest Death Trips in Essay Daily

Two Septembers in Brevity

And here’s an older one from Oklahoma Today:

January 15, 2022

Oklahoma Weird Wins Gold

Pleased to hear that my article on weird animals of Oklahoma, which appeared in the August 2020 issue of Oklahoma Today, tied for the Gold Prize for Nature and Environment articles at the latest International Regional Magazine Association awards. My late father helped me with the ideas for this one, which puts it especially close to my heart.

June 18, 2021

New Poem: Campfire

A lonely man, a campfire, photos of the one he lost. My latest poem appears in the May-June issue of Oklahoma Today. You can get the magazine here.

You can read some of my other recent poems free at these fine sites:

A river full of life you can barely see. "Kiss and Kill" in a back issue of Oklahoma Today.

A dark deed haunts his dreams. "Hope" in This Land.

Life blossoms in unlikely locales. "Irises Planted on a Grave" in Westview.

The night has a thousand eyes. . . and three thousand legs. "Beetles in Moonlight" in Westview.

April 22, 2021

My New Piece on Essay Daily

February 23, 2021

Even More Monsters: Wet Weather

European settlers reported them from the beginning—the hairy people called shumacki or sasquatch. Mostly they left humans alone, but there were some ugly encounters. On the Arkansas River in the winter of 1822, a hooting and growling band of shumacki pelted settlers’ cabins with stones and drove them from the territory. In 1870, workers with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad captured a juvenile and sold it to a carnival, which held it on display until it died, wheezing and pustuled, of smallpox. As late as last year, a shadowy figure stepped from a ditch near Lynnwood, Washington to leer at a stranded motorist. But the most brutal meeting in history happened on the Beaver River in 1882 during a spell of . . . Wet Weather.

“Wet Weather”: A new monster story from Gordon Grice. Part of The Cryptid Chronicles, available now from DBND Press.

And don’t forget Retro Horror, recently published by Nightmare Press, featuring the monstrous account of “Dippel’s Monkey” by Gordon Grice.

February 2, 2021

My Latest Monster Story: Dippels' Monkey

Check out my latest story--if you dare. Young Dippel has a brilliant mind and a hunger to prove his theories. This time, his experiments will bring him to the brink!

"Dippel's Monkey" appears in Retro Horror, a new anthology from Nightmare Press.

More Monster Stories by Gordon Grice

September 21, 2020

The Doomed Zoo

Our Trilogy of True Animal Terror concludes with the story of a great escape—and the tragedies that followed. “The Doomed Zoo”—a 7-minute listen.

Guliko Chitadze once dreamed of a tiger cage pooled with blood. Men were standing over some mutilated person, but she couldn’t see who it was. As a keeper at the zoo in Georgia’s capital city of Tbilisi, she had reason to worry about bloodshed. By US standards, the zoo wasn’t safe. Its arrangement of bars and fences allowed visitors to get too close to the animals. On more than one occasion, children had approached the tigers and been injured. Chitadze thought her dream was a prophecy of trouble to come.

Her real troubles started soon afterward with a little girl weeping. The girl, a zoo visitor, had accidentally dropped a toy into the tiger cage. Her father was trying to comfort her, telling her he’d buy her a new toy. Chitadze joined them, offering her own words of comfort. The girl was inconsolable. It was at this point the father said he’d go downstairs, to a place where he could reach into the cage and get the toy. Chitadze knew that was an extraordinarily bad idea. She offered an alternative: she’d reach the toy herself.

That, too, was an extraordinarily bad idea. It was against the safety rules; she could get hurt. Still, the girl was crying harder than ever, and Chitadze loved children, though she had none of her own. She wanted to help. The tigers weren’t particularly close to the corner where the toy lay. Probably she could reach in quickly, grab the toy, and be done without the tigers even taking notice.

Once downstairs, she slipped her right hand into the cage. She grabbed the toy and tossed it up and out. The grateful father was able to retrieve it. That’s when the tigers moved, too fast for her to react. One of them reached for her body through the bars. Its claws caught in her dress. She expected the dress to tear away as she pulled back, but it didn’t. Instead, the tiger pulled her to the ground and dragged her tightly against the cage. Another tiger reached out to take her by the hand. A third reached through the cage to bury its claws in her leg. With her free hand, she tried desperately to crawl away. She was held tight. The father screamed and came barreling down the stairs to help. She warned him to stay away, to go for other keepers. The second tiger had driven its claws through the flesh of her hand and was tugging as hard as it could to draw her into the cage. The pain was, she said, “soul-squeezing.” Of course, she could only have fit through the bars in pieces.

Suddenly she pulled her arm free. She was clear of the cage in an instant. Her right arm had no flesh from the elbow down. She lay there, nearly unconscious, as a veterinarian who worked at the zoo arrived to help. He tore his shirt into strips and tied one of them snugly around her upper arm, trying to stop the spurting blood. Otherwise, she’d die in minutes. She wobbled on the edge of consciousness, hearing everything around her. She had used this now-skeletal hand, she reflected, to raise a tigress named Salima from infancy. Salima was the mother of the three who had mauled her. She later claimed that Salima had come to her aid, had batted the three younger tigers aside to protect her.

At the hospital, doctors had to amputate most of the ruined arm. Chitadze made plans. She’d use a prosthetic arm to continue caring for the zoo animals.

She had already returned to work a month later when the waters began to rise. It was the spring of 2015; heavy rain swelled the Vere River. At Tbilisi, the dam broke. Cars floated sideways in the streets. Living rooms filled with mud. In places, the bank crumbled into the river, tearing apart the houses that had stood on top. People were swept away. The death toll eventually rose to 19. The flood struck the zoo as well. Despite her injury, Chitadze swam into flooded areas to rescue animals. She drowned in the attempt.

Some animals escaped their ruined cages. Wolves, bears, tigers, and eight lions were loose in the city. A bear was spotted on a second-story window ledge. A hippopotamus trotted through a major city square. Authorities warned people to stay indoors, or at least to stay away from garbage bins where the animals might come to scavenge a meal or wooded areas where they might hide. The hippo was shot with a tranquilizer dart and recaptured, as were some of the other escapees. But there were too few trained workers to cope with the mass escape. Police began to shoot the animals on sight. They felt the animals, especially the big carnivores, posed a threat to human lives. In that belief, they were right. Soon the Prime Minister of Georgia announced that all the dangerous animals had been captured or killed. In that belief, he was wrong.

Two days later, a party of workers entered a warehouse near the zoo to check for water damage. A white tiger sprang from the shadows. It had been hiding in the warehouse, and since all the large animals were thought to have been accounted for, no one expected danger. The tiger attacked one of the workers, a 43-year-old man. It bit him in the throat, severing a carotid artery. By the time he reached the hospital, he’d bled to death. Another worker suffered lesser injuries.

Police hunted the tiger down and shot it to death. As the prime minister apologized for the mistaken announcement, authorities learned that a hyena and another tiger might still be on the loose. It seemed only about half of the zoo’s 600 animals were alive and contained. Meanwhile the clean-up continued, with daily revelations of strange sights: The muddy carcasses of drowned bears. The elegant legs of an ostrich protruding from the ground. Paw prints in rusty mud. Empty cages pooled with rain.

September 14, 2020

Literature on the Wild Side

Literature takes a walk on the wild side when people clash with carnivores on the frontiers of Africa, Asia, and America. Our interactions with dangerous animals cast surprising light on race, gender, ecology, and even religion. These talks will touch on classic works of fiction by writers like Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle and vintage nonfiction by adventurers like Jim Corbett. For the first time, my lectures for the Selim Center will be available online.

Session 1 (September 22): The Man-Eaters of Tsavo

Two young lions brought British commerce to a halt, inspired books and movies—and set science on the wrong course for a hundred years. Twenty-first century biology sheds new light on this classic true tale from Victorian literature.

Optional Readings:

John Henry Patterson. “The Saga of the Man-Eaters.” This abridgment of Patterson’s book covers only the story of the man-eating lions.

Or, read his entire book.

Session 2 (September 29): Man into Wolf

Stories about wolves and other carnivores are almost always about something else—crime, war, or even the dark side of human nature. Classic writers like Rudyard Kipling and Robert Louis Stevenson show us why.

Optional Readings:

Jim Corbett-The Man-Eating Leopard of Rudraprayag

Rudyard Kipling. “The Mark of the Beast.”

Robert Louis Stevenson. “Olalla.”

Robert Louis Stevenson. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

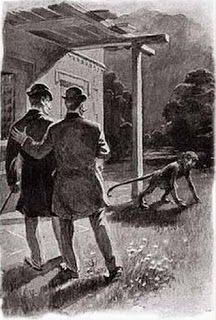

Session 3 (October 6): Sherlock Holmes Meets the Beasts

When Edgar Allan Poe invented the literary detective, he also invented its doppelganger—the motiveless malice of the animal. Arthur Conan Doyle refined both tropes in his finest tales.

Optional Readings:

Edgar Allan Poe. “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.”

Arthur Conan Doyle. “The Adventure of the Speckled Band.”

Arthur Conan Doyle. "The King of the Foxes."

Arthur Conan Doyle. “The Terror of Blue John Gap.”

September 7, 2020

Lost in America

The second in our Trilogy of True Animal Terror is quick and cruel as the bite of a hyena. Take 3 minutes to get “Lost in America.”

It was the largest hyena in the U.S. At least, that’s what Ganning’s Menagerie claimed. Zoo animals often led cramped, unhappy lives in the eighteen-fifties. A traveling menagerie like Ganning’s was even worse. Maybe that’s why the hyena had already bitten his keepers on a couple of occasions. Those bites were minor, compared to the ones it was about to bestow.

The trouble started when the caravan was camped amid the oaks and buckeye trees of northwestern Ohio. That’s where the hyena made its escape. History doesn’t tell us exactly how; in similar incidents, hyenas have gnawed through wooden doors.

Local men formed a search party. The trail led them to a cemetery. Hunger had driven the animal there. They realized that as soon as they saw the state of the graves—the disturbed earth, the intestines strung through the grass, the human pelvis jutting from a pair of pants.

The searchers closed in to capture the hyena. They imagined it would behave like a dog. That’s what it looked like, more or less. They realized they might suffer some nips or scratches . The first man to suffer a nip was a laborer named Jacob Poffenberg. It was a bit more than a nip, actually; it crunched his skull to fragments. He continued to breathe for a moment or two, and even to look at them with his remaining eye.

Turning to its next victim, who is described in a newspaper account as simply “a lad,” the hyena tore out the muscles of his arm by the roots, leaving him naked to the collar bone.

Now the hyena slipped away into the woods. Soon there was an ugly scene back at the menagerie, with hard words and the waving of torches. The Ganning people understood they were to leave the state and never look back. History does not say whether the hyena ever met another human being. If it did, that person did not return to tell of the encounter. For months the men searched the woods and swamps of the county, waiting to see the eyes of the carnivore shining among the sycamores.