Martin Fone's Blog, page 44

August 6, 2024

Malfy Originale Gin

I have tried a couple of the Malfy Gin range, con limone and Rosa, but not their Originale, which, as the name suggests, is their regular gin, an oversight I recently rectified when I saw it on special offer at my local Waitrose store. I have written before about the story of Torino Distillati, founded in 1906, so if you want more information follow the above links. Suffice it to say, that the distillery is within sight of the Monteviso mountain on whose slopes the wild juniper which is used in the gin grows and in whose spring waters the spirit is diluted to its 41% ABV.

This is very much an old school gin, using relatively few but traditional botanicals to make a classic London Dry style gin. As well as the local juniper, the distillers use coriander, cassia, orris, angelica root, orange and lemon and grapefruit peel. On the nose there is the reassuringly heavy presence of juniper, punctuated with hints of coriander and citrus. In the glass it is clear, crisp, and dry, the aniseed and spicy coriander combining to good effect with the juniper. It is a no nonsense gin, using tried and tested botanical combinations and is none the worse for that. Often it is a pleasue to get back to basics.

The spirit is contained in a bottle that oozes class and style. It is cylindrical, with clear glass, a flat shoulder and short neck leading to a fat, wide lip with a wooden top and synthetic cork. Embossed on the glass is “Italy” and “GQDI” which stands for “gin di qualita dall’Italia”. What makes it stand out is the use of a vibrant light blue and rather squashed circles that give it a cool and contemporary look. This is Italian chic.

A great gin which I will certainly be returning to.

Until the next time, cheers!

August 5, 2024

Death On The Nile

A review of Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie – 240715

It is an odd feeling reading a book for the first time that has a story you have seen adapted countless times. I am going through Christie’s Poirot series in chronological order and Death on the Nile is the seventeenth, originally published in 1937. When it came up in my TBR pile I was tempted to give it a miss as I already knew whodunit, always a bit of a bummer with a murder mystery, but the completist streak in me together with an interest in how far the adaptations strayed from the original got the better of me. I am glad they did.

Inspired by her journey down the Nile on the Karnak in her teens, this has all the classic Christie hallmarks – a title that prosaically tells you what it is all about, an exotic location, three principal murders, a complex plot full of red herrings, and the ubiquitous Hercule Poirot who has yet another busman’s holiday. A river cruise allows her to gather together an eclectic array of characters and, as they are trapped on the boat for seven days, they have no opportunity to escape and the culprit must be amongst their number.

A little knowledge is always a dangerous thing as the maid, Louise Bourget, and the eccentric authoress, Salome Otterbourne, find out as they have information that could have unmasked the murder of the heiress, Linnet Doyle née Ridgeway. However, they are quickly eliminated, but their deaths only confirm Poirot’s analysis of what happens. If I had not known the outcome, I wonder whether I would have twigged what was going on. We will never know for sure, but Christie does leave enough clues lying around to make sense of it all.

The Karnak is a veritable cesspit of intrigue and wrongdoing. We meet dear old Colonel Race again, previously seen in Cards on the Table, who is on the hunt for a spy. A telegram about vegetables quickly disposes of that. Then there is the theft of Linnet’s necklace and an attempt to defraud her, a different perpetrator each time.

Death on the Nile is a bit of a morality tale. Linnet is spoilt, used to getting her own way, and callously snatches the fiancé of her friend, Jacqueline de Bellefort, and quickly marries him. She is set up to get all that she deserves and there is no doubt that Christie intends that we do not spend an ounce of sympathy on her. Jacqueline, in modern parlance, stalks the newly weds and her constant appearance even pricks the conscience of the normally uncaring Linnet. Justice of sorts is done and the reader is left to ponder on whether the ends justify the means. Of course, to Poirot murder is murder and the taking of a life is the most heinous crime. With such a clear philosophy, only the truth unblemished by any sense of sympathy can prevail.

As well as using her own experiences for the novel, Christie drops little reminders of some of her previous books in the text. Poirot is reminded by Miss Van Schuyler of a mutual acquaintance, Mr Rufus Van Aldin (The Mystery of the Blue Train), remembers the red kimono planted in his luggage (Murder on the Orient Express), and credits his experience in Murder in Mesopotamia with the development of his detective expertise.

Subsequent adaptations do miss a lot out, making the plot less complex, which is why the original book is always best. The characters might be a little linear and the dialogue often wooden, but there is a good story here told by a master at their craft. It is rightly one of her best.

August 3, 2024

Covid-19 Tales (27)

One of the (many) mysteries of the Covid epidemic is why some people have so far escaped infection. The reason might be revealed in the results of a study carried out by Dr Marko Nikolić and his team at University College London in 2021 which have been recently published in Nature.

36 healthy adult volunteers who had no history of having Covid and were unvaccinated were given a low dose of the virus through the nose. With 16 of the volunteers the researchers monitored activity in immune cells in the blood and lining of the nose. While six developed a sustained infection and became ill, three became transiently positive but never developed a full infection, while seven experienced an abortive infection, never testing positive and mounting an immune response.

In the latter two groups, tests taken before they were exposed to Covid showed that they had high background levels of activity in the HLA-DQA2 gene which flags danger to the body’s immune system. The study suggests that those with a high level of activity in this gene may have a more efficient immune response to Covid which goes some way to preventing the infection getting beyond the body’s first line of defence.

However, a word of caution. High levels of HLA-DQA2 gene activity does not mean that heredity has dealt you a get out of jail free card: some of the volunteers went on to catch Covid in the community.

It’s the genes by a nose.

August 2, 2024

Six Were Present

A review of Six Were Present by E R Punshon – 240711

And so the career of Bobby Owen which has spanned thirty-five novels draws to a close. Originally published in 1956, the year of Punshon’s death at the grand old age of 84 and reissued by Dean Street Press, the author and his publisher persist with their established tradition of selecting uninspiring and uninviting titles. Six were Present is an accurate description of the number of suspects who were present at the seemingly impossible murder of Val Outers but is not one that is designed to set the heart racing. It might explain why this distinguished and underrated author quickly fell into obscurity.

It is another case of a busman’s holiday, with Bobby Owen on leave from Scotland Yard taking a motoring holiday with his wife, Olive, one of the ports of call being Constant Freres, the home of his cousin, Myra Outers, her husband, and daughter, Rosamund. It is a childhood haunt and it brings a distinct sense of the circularity of Owen’s career, his last case taking place in a house that he knew well in his youth. There is an eerie, almost Gothic, sense about the place with its crumbling ruins and its tall tower, Folly Tower, both of which are to have a significant bearing on the story.

To add to the sense of eerie foreboding Myra has contacted Bobby because she is worried. The Outers host spiritualist sessions led by Teddy Peel, am an known to the police who claims to be a sensitive and imbued with electric magnetism. During one of the sessions they hear a voice mumbling in an African dialect which brings back memories of their tragic backstory and the phrase “by death set free”, a phrase used by a witch doctor to Rosamund, later modified to “through death set free”.

The Outers spent time in Africa and lost their two sons, who were never seen again after trying to spy on some native rituals. Val has a bag, which he claims to have been given to him by a witch doctor and calls a medicine bag, which he has never opened but inside he believes there to be a map showing the whereabouts of the largest deposit of uranium in the world. Val has never acted upon it because to do so would spell the end of the tribe’s existence and lands, a sensitivity that must have been rare amongst colonials at the time, even though there is more than a little of the white supremacist attitude in the story.

Rosamund has attracted two suitors, Ludo Manners and Baynham, known as B.B. Were they attracted to Outer’s daughter or to the potential fortune that is sitting in his bag? The sixth present at the fatal séance was the housekeeper, the remarkable Mrs James, the star of the story, who has only one leg and performs prodigious feats of athleticism with her crutch, a mobility aid that has more than one purpose. Mrs James has a disabled son, Dewey, who has shown an interest in Rosamund and was openly despised by Val Outers.

Inevitably, after the Owens have left, Val is fatally stabbed during another séance and the medicine bag disappears. Bobby is called back, leaving Olive to return to London and never to be heard of again, and joins the local Inspector, Nixon, on an unofficial basis to investigate. Bobby, of course, is in a tricky position as two of his relatives are high on the suspect list, if there is any credence to be paid to the witch doctor’s curse, but he is the consummate professional throughout, weighing up carefully every bit of evidence and everything that is said, painstakingly painting a picture of what happened.

If I was to be overly critical, despite the plot’s twists and turns and the multiplicity of motives, Punshon rather telegraphs the solution with a constant reference to a peculiarity that ultimately proves telling. That said, it was an entertaining story and a fitting conclusion to a wonderful series. That it was the end of Bobby Owen’s fictional career is foreshadowed by Nixon’s remark that Owen should write his reminiscences, something people do when they retire. Fortunately, Punshon had done that for him and Dean Street Press are to be congratulated in breathing new life into a sadly neglected series.

As an added bonus, the edition includes the previously unpublished script of a 1941 play, Death on the Up-Lift, featuring Bobby Owen. Great stuff!

August 1, 2024

Grey Owl

In late 1935 one of the hottest tickets in England was to attend a lecture given by an imposing figure of a man, tall, hawk-nosed, dressed in buckskin and wearing magnificent feathered headgear on his braided hair who, once a beaver trapper in Canada, had reinvented himself as an ardent conservationist. By the time Grey Owl had stepped off the Empress of Britain in Southampton on October 17th he was already a popular author with three books and numerous articles to his name.

His Damascene moment, according to Grey Owl’s account in Pilgrims of the Wild (1935), came when, after trapping and killing a mother beaver, he was haunted by the cries of the kittens which resembled the sounds of human babies. The following day, piqued by the protestations of his wife, Anahareo, a woman of Mohawk Algonquin descent, he went back to rescue and adopt the babies.

From that moment he railed against the cruelty of beaver trapping, a timely volte-face as numbers of beavers, valued for their waterproof pelts and castoreum, a yellowish secretion used for perfume, had plummeted to dangerously low levels in Canada. “Every word I write, every lecture I have given or ever will give”, Grey Owl wrote in 1936, “were and are to be for the betterment of the Beaver people, all wild life, the Indians, and half-breeds, and for Canada, in whatever small way I may”.

His message was simple but powerful. Canada’s greatest asset was its forest lands and the plundering of the country’s hinterland had to stop. Humans belonged to Nature not Nature to them. As well as being ahead of his time, a forerunner of modern day conservationists, his message seemed more potent as he epitomized the noble savage, possessed of a natural insight into the world around him.

Grey Owl’s lecture tour of England attracted around 250,000 people, including the Attenborough brothers, Richard and David, who queued outside a Leicester theatre for five hours to hear him. Grey Owl went on to touch their adult lives, David being inspired to become one of Britain’s foremost naturalist and conservationist while Richard went on to direct the biopic, Grey Owl, in 1999, starring Pierce Brosnan, although he claimed that it was an article in Country Life by George Winter commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Grey Owl’s death that reminded him of his childhood encounter.

The lectures followed a similar format. After a few words of welcome, Grey Owl would show a film, Pilgrims of the Wild, about his life at Beaver Lodge by Lake Ajawaan in Saskatchewan, telling stories in a natural and engaging style and giving insights into the lives of beavers as the film ran. The diplomat, Georges Vanier, noted that “all those, and they are legion – who have come in contact with him, have been much impressed by his knowledge, his simplicity and by his manners who are instinctively of a gentleman in spite of his long and almost continuous life in the woods”.

The demand to hear his story proved insatiable and in the autumn of 1937 he was back in Britain giving 140 lectures, including a Royal Command Performance at Buckingham Palace on December 10th attended by King George VI and his daughters. He followed this up with a tour of North America in early 1938 but the strains of touring had taken its toll on his health.

On April 13, 1938, at the age of 49, he died of exhaustion and pneumonia, his friend, Major J A Wood, observing that “at 8.25 in the morning, he died very quietly and pictures taken show that the congestion in his lungs was very slight, which all goes to prove that he had absolutely no resistance whatever”. He was buried on the ridge behind Beaver Lodge.

July 31, 2024

Howzat!

I was saddened the other week to hear of the death of Frank Duckworth, a statistician who found enduring fame by devising, along with Tony Lewis, a method for more equitably settling the result of a limited overs game of cricket interrupted by the weather.

Recognising that there were only two factors, or in their terminology resources, that affected the ultimate score of a team, the number of balls remaining and the wickets in hand, they developed a system which took into account the resources used by the team batting first to adjust the target score for the team batting second, taking into account the state of their resources at the time of the interruption. Ther method was computerized and first used on January 1, 1997 in an One Day International between Zimbabwe and England which the hosts won by seven runs.

The 3,000 meter steeplechase is a gruelling enough competition for athletes, with twenty-eight hurdles and seven water jumps to negotiate without having to deal with administrative incompetence. In the event in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, the Finnish athlete, Volmari Iso-Hollo, was over 35 meters ahead of his rivals when he reached the 3,000 meter point only to find that the official in charge of the lap counter forgot to record the first lap, which meant that each athlete had to run an extra 460 meters.

Fortunately, Iso-Hollo was sufficiently ahead of the field that he won the elongated race, but there was a problem in the silver and bronze medal positions. The American athlete, Joseph McCluskey, was second at the 3,000 meter point but was pipped at the post by the British runner, Thomas Evenson, in the elongated race. When the lap error was discovered, McCluskey was offered a re-run the following day but he refused the offer, saying “a race has only one finish line”.

The other problem was what to do about the time. The officials scratched their head and somehow came up with a method that adjusted Iso-Hollos finishing time of 10 minutes 33.4 seconds down to 9 minutes and 18.4 seconds. The unfortunate consequence of this adjustment was that the revision made Iso-Hollos’ finishing time an Olympic record. There was too much guess work to allow this to happen so the records show Iso-Hollo’s winning time as the one he recorded after running 3,460 meters.

Where was Frank Duckworth when he was needed? May he rest in peace.

July 30, 2024

Hendrick’s Flora Adora Gin

While I am forever grateful for the skills of a distiller, I wonder whether, after perfecting the way to create the flavour profile of the type of gin you want to produce, it all gets a little boring and whether there is an irresistible urge to tinker with the product or create something new. That is obviously why we get variations around an original gin recipe and experiments with ever more outlandish combinations of botanicals.

The master distiller of Hendrick’s, Lesley Gracie, has partially resolved the distiller’s conundrum by launching the Cabinet of Curiosities limited editions of which Hendrick’s Flora Adora Gin is the fourth. Inspired by her observations of the pollinators at work in her Ayrshire coastal garden, using the blooms that particularly attracted their attention, she has produced a distinctly floral and unusual gin. To say that it is a floral gin is somewhat of an understatement.

On the nose it is unmistakably sweet and floral, a big hit that is reminiscent of a walk in a particularly perfumed garden designed to tickle the senses, but there is much more, a hint of fruitiness and pepper and a hint of juniper desperately flailing in a sea of pot-pouri-like sweetness.

In the glass it is clear and on the first sip there is something which takes the breath away, not necessarily in a good way. Once the initial shock has dissipated it settles down to reveal heavy floral notes, particularly rose, violet, and elderflower which combine with heavy orange oil and fresh peppers. Surprisingly, it is quite refreshing, perhaps due to the use of Hendrick’s signature cucumber, and has enough heat to counter the intense sweetness of the gin.

The botanical line up includes juniper, chamomile, elderflower, hibiscus, lavender, and yarrow with the Hendrick’s staples of rose and cucumber. There may be more, who knows? The base spirit is grain and the finished product has quite a punchy ABV of 43.4%. Unique is an overused and often misused adjective but I think it is fair to say that Flora Adora is like nothing else on the market and for that alone is worth a try.

The spirit is housed in the familiar Hendrick’s dumpy, circular apothecary-style bottle with its short neck and cork stopper, using dark glass against which the pinky-orange labelling stands out well. The label includes an image of the all-seeing eyes of a butterfly to reinforce the message that the gin finds its inspiration from the cretaures that we are encouraged to attract to our gardens.

The usual Hendrick’s quality is assured and if you like sweet, floral gins this will float your boat. For me, though, I like to taste my juniper.

July 29, 2024

Sweet Poison

A review of Sweet Poison by Mary Fitt – 240709

Taking its title from a line from Shakespeare’s King John, Sweet Poison is the eighteenth in Fitt’s Superintendent Mallett series, originally published in 1956 and reissued by Moonstone Press. To call it a Mallett story is almost stretching a point, though. Yes, he and his medical companions, Fitzbrown and Jones, feature in the book but theirs is a very desultory investigation, only too willing to accept the coroner’s verdict of suicide and, perhaps, even failing to recognize that there is more than one biniodide tablet missing from Roger Royden’s first aid bag. It is less a conventional murder mystery and more a comedy of manners, and none the worst for that.

The story is dominated by a larger than life character, Augustus Gale, who has become so obsessed with an 18th century writer, Joan Farmer, whose life span exactly matches that of jane Austen, that he has bought her old home, Geffrye House, set up a museum in honour of her and has adopted a Regency-style lifestyle, including dining at five o’clock, which he has imposed on his family. He is in a loveless second marriage to Dulcibella with whom he has two small children and two children from his first marriage, Cornelia and Rupert, both of whom in their different ways, hate him. To complete the menage there is Augustus’ mother, Mrs Gale, Professor Bose, who seems to encourage Augustus in his obsession and has been affianced to Cornelia, Miss Smith, the secretary, and the much put upon servant, Robert Brooke.

A cat is put among the pigeons when a rare Roman mosaic is found adjacent to Geffrye House and part of it goes on to Gale’s land, directly underneath a hillock where Joan Farmer’s summerhouse once stood, a place of especial significance to Augustus. A party of archaeologists, principally Riley, Martin Praa, and Roger Royden, are working on the site outside Geffrye House and want Gale’s permission to carry on their excavations on his land. Gale, a man who enjoys inconveniencing as many people as possible, resolutely refuses and to try to resolve the situation Dulcibella finesses an invitation for the archaeological trio to stay at the house. By this time Roger has fallen in love with Dulcibella and they are talking of elopement. What possibly could go wrong?

With more than enough people with an axe to grind against Gale, it is no surprise that he dies of poisoning in circumstances which are somewhat suspicious but the authorities and police are happy to the death as suicide, much to the relief of Roger, who, having brought the poison into the house and having fallen for Augustus’ wife, is the prime suspect. Of course, there is a different version of events, which Roger discovers in a final conversation months after the event, and confirms the impression that an astute reader might have gathered as Fitt unfolds her tale. Worms do turn and every dog has its day.

In many respects Gale’s death is more of a sideline and the book is really an exploration of obsession, both Gale’s for Joan Farmer, and the archaeologists’ for the preservation of the mosaic, and what happens when they collide and also how one person’s domineering obsessive personality can mould and influence the behaviour of others. Fitt writes with humour, intelligence and has an engaging style. The tale is told in a straightforward fashion, the reader is given as much information as they need to make and there is little in the way of padding. The book ends with a synopsis of the fates of the principal characters. The moral of the story is that a house guest should not come armed with poison.

It makes for an enjoyable light read from an author who has been sadly neglected and Moonstone Press deserve credit for bringing some of the works of the classics scholar Kathleen Freeman’s alter ego to the attention of the modern reader.

July 27, 2024

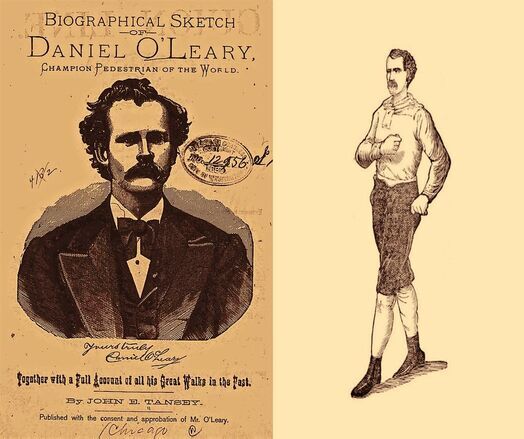

Daniel O’Leary

The American pedestrianism craze attributable in no small part to the feats of Edward Weston gave the disadvantaged an opportunity to escape their lives of grim poverty. One who seized the opportunity with both feet was a thin, moustachioed Irish emigrant by the name of Daniel O’Leary.

Arriving in New York in 1866 he made his way to Chicago and inspired by the thought that anything a teetotalling Yankee could do, a hard-drinking Irishman could do better, O’Leary hired a roller rink on the West Side of Chicago and announced his intention to walk 100 miles in twenty-four hours. Fortified by iced water and brandy and enduring stifling conditions and a rickety track, he set out at 8.30pm on July 14, 1874 and completed his feat with forty-three minutes to spare. At the same rink a month later he walked 105 miles in 23 hours and 38 minutes.

Stung by Weston’s response to a challenge that he should “make a good record first and meet me after”, O’Leary broke Weston’s record of 115 miles by walking 116 miles in 23 hours, 12 minutes and 53 seconds at a rink in Philadelphia in April 1875 and knocked 2 hours, 28 minutes and 10 seconds off Weston’s cherished record of walking 500 miles in under six days at a rink in his adopted home of Chicago. Over five thousand crammed in to see the culmination of the feat, for which he was presented with a gold medal by the local Irish community.

The Philadelphia Times took note, declaring that “Weston will have to look to his laurels for all of a sudden, in the height of his fame, a competitor spring up who bids fair to throw his best feats into the shade”. O’Leary’s feats were celebrated in a popular piece of doggerel which ran “Attend, you loyal Irishmen, of every rank and station/ I pray draw near and lend an ear in a distant nation;/ with right good will I take my quill, and never shall get weary/ to sing the praise of that noble youth – brave Dan O’Leary”.

Weston had no option but to accede to O’Leary’s challenge and the two met in two competitions to walk 500 miles within six days, the first held in Chicago in 1875 and the second in London in 1877. O’Leary won them both. There was a new champion.

O’Leary won races not only in the United States but also in Canada, France, England, Australia, and Ireland and earned the Astley Belt, awarded to the “Long Distance Champion of the World”. But perhaps his most remarkable feat was achieved at the age of 63 in Norwood near Cincinnati when he attempted the Barclay Match, walking a mile an hour for 1,000 consecutive hours.

Curiously, the medical profession seemed to be unaware of previous successful attempts and part of O’Leary’s rationale for attempting the feat was to disprove the current theory that the body could not withstand such physical strain.

There was something of a carnival air when he set out on September 7, 1907 with the mayor of Norwood joining O’Leary on the first mile and a Miss Pauline Holscher completing two miles for every of his on roller skates. Unlike Barclay, he walked at the top of each hour, reducing his rest time to three-quarters of an hour, and by mile 600 he was reported to be “haggered” and “showing signs of tremendous strain on his nervous system”.

Despite doctors recommending the use of stimulants, he then suffered from a sore left foot, caught a cold, and suffered from bad nose bleeds. Nevertheless, at mile 925 the doctors proclaimed him to be in “first-class condition” considering and on his final day thousands came out to watch.

The carnival vibe was repeated with a ladies’ walking contest, a ten-mile relay walk, and a free-for-all boys’ walk. At the end he had lost 14 pounds in weight but the purse of $5,000 and his share of the “considerable” gate money would have assuaged any discomfort.

As he once said, “I never stay in one place long enough to get stale. Life is always fresh to me. That is my secret”.

July 26, 2024

The Gazebo

A review of The Gazebo by Patricia Wentworth – 240706

The twenty-seventh novel in Patricia Wentworth’s Miss Silver series, originally published in 1955 and with an alternative title of The Summerhouse, is an interesting if somewhat low-key study into the ways of provincial life and has an almost timeless feel about it. Aside from the reality of the murder of Althea Graham’s manipulative and deeply unpleasant aunt, Mrs Graham, the plot would not be out of place in a Victorian melodramatic novel.

Althea had fallen in love with Nicholas Carey but her aunt vetoed their engagement five years ago and Carey went off travelling. On his return their love was rekindled and they decided to marry without the aunt’s approval. However, Mrs Graham after overhearing their plans confronted them in the gazebo in the grounds of Grove Hill, there was an argument and Althea led her back to the house and put her to bed. Later that night Mrs Graham got up again, went to the gazebo again, was overheard mentioning Nicholas’ name and is found dead the following morning, having been strangled.

The obvious suspect is Nicholas, especially as, according to the Yard detective Frank Abbott, his time amongst the savages of Africa could have affected his behavioural values. Althea, though, has had the sense to invite Miss Silver to protect her interests and the knitting sleuth is more than a little interested in the history of Grove Hill, which was burnt down during the Gordon Riots, immortalized in Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge, and why two rather unsavoury characters, Blount and Worple are bidding against each other and willing to buy the house at more than the market value.

It does not take a genius to work out that there is something of considerable value is buried in the grounds and rather than being the victim of a vengeful lover, Mrs Graham might just have been in the wrong place at the wrong time. Miss Silver makes it her mission to uncover the truth and dissuade her favourite detective, Frank Abbott, from making a monumental mistake.

Wentworth fills her village with some wonderful characters, not least the Pimms’ sisters, three spinsters whose life work is to be the medium through which all the village’s tittle tattle passes. The middle sister, Lily, has the useful knacks of being acutely observant, recognizing that the volatile Mrs Harrison had lost a stone from her ring on the night of Mrs Graham’s murder, a stone which, of course Miss Silver finds in the gazebo, and an unerring ability to recall conversations verbatim, a skill which is less helpful to Nicholas’ cause. Several of the villagers in their different ways attempt to put two and two together to solve the mystery.

There are also some awful characters, Mrs Harrison who throws valuable antiques at her rather unworldly husband, Mr Blount who leads his nervous wreck of a wife a dog’s life, and Mrs Graham who uses ill-health to reduce her niece to little more than an unpaid domestic help, squeezing all the vitality out of her. That is why the return of Nicholas was so welcome and the suspicions over his actions were so hurtful.

Anyone who has lived in a village will recognize that there is a deep divide between those who were born and bred there and the newcomers, the latter being viewed with deep suspicion by the former. Even Nicholas loses his native status for having the temerity to break away for five years. Wentworth captures this aspect of life to a T in a novel which, but for the occasional gripe at the level of taxation, shows little evidence of having been set in a country reconstructing itself from the ravages of war. It was also interesting to see two hen-pecked spouses get their own back, adding to overall sense of the restoration of natural justice at the end with each of the main protagonists getting their just desserts.

A tad over long it may be and with a rather thin plot, nevertheless Wentworth knows how to write an engaging and entertaining story. Miss Silver and Frank Abbott in their different ways, naturally, come up trumps again.