Martin Fone's Blog, page 40

September 21, 2024

Lovecraft’s Legacy

A perfectly preserved fossil specimen of a 430 million-year-old relative of the sea cucumber was found in the Herefordshire Lagerstätte formation, according to a study published in 2019 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. A 3D reconstruction not only showed that it crawled around the seabed on its 42 tubed feet to scavenge food but that it was also a distinct species.

Of course, this meant it had to be given a species name. This is where H P Lovecraft comes in. In his short story, The Call of Cthulu, published in the American pulp magazine, Weird Tales, in 1928 he introduced his readers to a tentacle-headed monster that hibernated in the the underwater city of R’lyeh in the South Pacific.

It seemed a perfect fit for the tentacled ancestor of the sea cucumber which was given the scientific name of Sollasina Cthulhu.

Pulp fiction is not all bad!

September 20, 2024

The Bungalow Mystery

A review of The Bungalow Mystery by Annie Haynes – 240816

Annie Haynes does not hang around in opening her first murder mystery, originally published in 1923 and reissued by Dean Street Press. Dr Roger Lavington is summoned by the distressed housekeeper of his neighbour, Maximilian von Reinhart, because her employer has been shot dead in the eponymous bungalow. When Lavington gets to the scene of the crime, he finds a young woman hiding behind a curtain, clutching a package.

The woman pleads her innocence and Lavington, as well as falling in love with her, aids in her escape by getting her to pose as his cousin. She gets away, although she is partially recognized by an old man, a former judge known as “the Hanging Judge” who will have an important part to play in the story’s eventual denouement. The woman the police think was involved at the scene is then killed in a train crash which also so severely maims Sir James Coutenay that he has to have both legs amputated. This seems to put the case to rest only for it to be resurrected two years later when fresh evidence emerges.

This is another case where wo characters with similar appearances have a prominent part to play in the plot. Lavington is convinced that the woman he helped was Elizabeth Luxmore whose sister, Daphne, was engaged to Sir James until his accident, but he cannot be certain and doubts grow as the story progresses. Lavington confesses his feelings for Elizabeth to a woman he believes to be her sister and his determination to protect her is enhanced with the arrival of Reinhart’s widow, presumed dead, who is determined to seek justice for her husband.

Sir James gets dragged into the story because he was seen and heard arguing with Reinhart just before the murder and his embossed cigarette case is found at the scene and he is arrested and put on trial. It is at this point that the Hanging Judge, Sir William Bunner, intervenes. For the majority of the book, the investigations have only focused on two people, Sir James and Elizabeth Luxmore, but Bunner, with a fresh pair of eyes and a more forensic approach, widens the scope to include two more, one of whom almost immediately breaks down and confesses. For Lavington and Sir James the story concludes happily, not least because of the skill of Italian surgeons, the latter is fitted with prosthetic limbs that allow him a degree of movement.

Lavington is the most interesting character, a man who seemed to react to situations as they emerged in a way that was calculated to make them worse. The obvious course, as Bunner pointed out, upon discovering the woman at the scene was to make her stay and give her evidence to the police, especially if she was innocent. Instead he concocted a plan which cast her in the worse possible light. It was if, as Bunner said, “he wanted to fix suspicion on her” and to his forensic eye, but for the want of a motive, would be enough to put Lavington in the frame.

Much of the story is seen from Lavington’s perspective and, whilst not a sleuth, in his rather ham-fisted way he tries to get to the truth, albeit motivated by love, without getting anywhere near the solution. The various policemen, good at following suspects and taking up disguises, are equally useless, taking too much at face value and not stepping back and reassessing the case. The revelation of true identities is at the heart of the case.

Haynes’ prose style is a little stilted by modern standards, but once the reader gets used to it, the story zips along. From the armchair sleuth’s perspective, there is too much vital information dropped in, especially as the novel reaches its denouement, for it to be classed as a fair play novel. However, the story is gripping and, for this reader at least, draws much of its power from the feeling, at times shared by Lavington himself, that the damsel in distress might not be as innocent as he and we hope her to be. Bunner, though, the one grown up in the room, rides to the rescue.

September 19, 2024

Whitley Neill Distiller’s Cut London Dry Gin

The very first distillery I visited was the City of London Distillery. Sadly, Jonathan Clark moved on to pastures new and the original COLD range disappeared into the wastelands of the ginaissance but the vacuum left was filled by the ubiquitous Whitley Neill range of gins. I have observed before that the distiller’s job can be a rollercoaster but once the perfect calibration has been achieved it becomes more mundane, maintaining the level of consistency required for a commercial proposition.

Some distilleries, to spice things up, test the distiller’s mettle by challenging them to create a variation around a theme. This is what Hendrick’s have done with varying success with their Cabinet of Curiosities range and Whitley Neill have followed suit with their Connoisseur’s Cut and their Distiller’s Cut. At a reasonable price of £20 at the local Waitrose I took a chance on the latter.

It is a homage to dried orange peel, which is no bad thing, which takes its place alongside the familiar and equally welcome botanicals of juniper, coriander seed, angelica root, cassia bark, and liquorice root, amongst others. This is not an experiment to find a workable combination from a range of exotic and disparate botanicals but an examination of the potential that turning up the dial on orange brings to a classic array of London Dry style favourites.

The result is an attractive and complex gin. The aroma is a heady mix of juniper and orange with hints of earthiness and spice while in the glass the juniper provides a solid background to emphasise the citric notes of the orange while the coriander and cassia provide depth and spice. It has a slightly oily feel in the mouth and there is a long, smooth, slightly spicy aftertaste that is moreish.

The bottle and labelling is the familiar Whitley Neill design which uses a marine blue coloured glass. With an ABV of 43% it is a welcome standard to the gin shelf, to be brought out for those moments when my palate is feeling a little less adventurous than normal.

Until the next time, cheers!

September 18, 2024

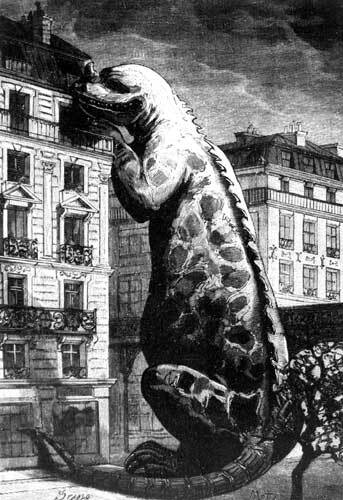

Dinomania

A pile of dinosaur bones are not dramatically attention grabbing in their own right but what made the original paleontologists stand out from their archaeological colleagues was the way that they presented their finds to the public. For the Great Exhibition of 1851 Richard Owen commissioned the sculptor Waterhouse Hawkins to create life-sized reconstructions of dinosaurs. Famously, a dinner party was held inside a half-built Iguanadon and after the Exhibition the models were moved to Crystal Palace Park.

Over in the United States the first articulated skeleton of any dinosaur was found in 1858 in a New Jersey clay pit. Called a Hadrosaurus Waterhouse Hawkins was employed to mount it and then took casts of it which were offered for sale to museums around the world. His mounted skeleton caused such a stir that the Academy of Natural Sciences had to starting charging for admission to limit the numbers of onlookers.

Clearly the sight of a dinosaur had the potential to fire the human imagination but the mounting of bones still required a little effort on the part of the onlooker to bring the creature to life. Camille Flammarion’s book, Le Monde avant la Création de l’Homme (1886), began to put some flesh on the bones with an illustration of an Iguanadon taking a meal on the fifth floor of a Parisian building. Later American newspapers such as American Century in 1897 and New York World and Advertiser (1898) ran illustrations of the far larger Brontosaurus against a background of skyscrapers.

Although extinct dinosaurs, at least in the public imagination, were big, strong, and ferocious and as the largest-ever land animals, they symbolized power. Toy manufacturers began to realise the potential of the dinosaur to attract the imagination of a child and used the fanciful reconstruction of the paleoartists to create thin, scaly figurines. Unfortunately, they were a far cry from what scientists now think the creatures looked like, but, technically inaccurate as they might have been, they found a ready market.

During the 1960s and 1970s scientists developed a greater understanding of dinosaurs, including that most of them had feathers, but although these findings were in the public domain, it was often not commercially viable for manufacturers to change moulds to keep up to date.

The game changer was the release of the film Jurassic Park (1993) which sparked a new wave of dinomania. Children wanted models of their favourite characters, finally prompting model manufacturers to change and update their moulds. That the film depicted some species inaccurately did not seem to matter. Dinosaurs were now firmly established as the must-have toys for children.

September 17, 2024

The Sharpest Tongue (3)

In less politically correct times in schools children who came bottom of the class or were struggling at particular subjects were called dunces and were even forced to sit in the corner wearing a pointed hat. In my day, I recall the term being used, although no one was forced to sit out or wear a hat. Nowadays, of course, teachers will strain their thesaurus to find an adjective that gives a scintilla of encouragement to the floundering student.

I had never given much thought to the origin of the term “dunce” but it turns out that it gives a fascinating insight into the religious struggles of the 16th century. John Duns Scotus was a 14th century scholar whose works were enormously influential in Western philosophy and theology, his proof of the existence of God, according to the 20th century monk, Thomas Merton, the best that has ever been offered.

However, with the rise of Protestantism and humanism during the following century the contribution of Scotus to religious thought underwent a sea change. By 1587 the English chronicler, Raphael Holinshed, was observing that “it is grown to be a common prouerbe in derision, to call such a person as is senselesse or without learning a Duns, which is as much a foole”.

Curiously, though, as John Lyly noted in his Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578), “if a person is given to study, they proclayme him a duns”. It is thought that the humanist contempt od the scholastic method and style of the likes of Scotus conflated the concepts of foolishness and studiousness into the pejorative dunce. After all, a person would be wasting their time reading Scotus.

One of Scotus’ adherents, Nicholas de Orbelius, also gave his name to a pejorative educational term. Dobel was used to describe a scholastical pedant, a dull-witted person, a dolt.

O tempora, o mores!

September 16, 2024

Tour De Force

A review of Tour de Force by Christianna Brand – 240813

The sixth book in Brand’s Inspector Cockrill series, originally published in1955 and reissued as part of the British Library Crime Classics series, sees Cockie take a well-earned holiday, a package tour around Italy. Inevitably, when the representative from Scotlanda Yarda reaches the quasi-independent island of San Juan el Pirata, some twenty kilometres off the Tuscany coast, it turns out to be a busman’s holiday.

Package tours were still something of a novelty and Brand exercises her jaundiced and cynical eye in describing the types who are attracted to such a holiday, the Vulgars and Jollies, the Timids, the Seasoned Travellers, the Neurotics and the Hearties. She then narrows her focus to concentrate on a varied collection of trippers who will play their part in the murder mystery. They include a novelist, Louvaine Barker, who experiments with beauty treatments and fashion tips culled from magazines, Miss Trapp who is believed to come from Park Lane although her hat is dates, the camp fashion designer, Mr Cecil, Vanda Lane, the Rodds, Leo a former concert pianist who lost his right arm in a freak cycling accident and who, surprisingly, seems to be a hit with the women, and his long suffering wife, Helen. Making up the octet are Cockrill himself and the suave opportunist of a tour leader, Fernando Gomez.

There are more than a few similarities with Nicholas Blake’s later The Widow’s Cruise. There is the hint of blackmail, a tour manager who is more interested in enhancing his love life than in the personal welfare of his charges, two characters who share more than a few physiological similarities and an almost impossible murder where the prime suspects have seemingly rock solid alibis.

Vanda Lane is found murdered in her room, having been laid out on a bed on top of Louvaine Barker’s red shawl. There is a book on a table, splattered with blood, which contains notes about each of the tour group and with a financial sum against each, indicative of the amount a potential blackmailer might seek to extract from their victims. Unfortunately for Cockie, it is open on a page devoted to him.

At the time of the murder, all the six suspects were visible to Inspector Cockrill, leading the local police to suspect that either Cockrill fell asleep for a while, a suggestion that he vehemently denies, or that it was he himself that was the murderer. Cockrill even has the indignity of having his own collar felt and a few hours in the local insalubrious jail.

There is more than a little xenophobia running through the story. The San Juanese are portrayed as being corrupt and incompetent with Cockie lamenting that his ability to solve the case is hampered by his lack of finger printing equipment and the inability to harness the resources of the Yard. One of the interesting features of the book is that the murder method is revealed relatively early in the investigative stage but the ultimate resolution is a mirror image of it. In between there are reconstructions that show that most of the prime suspects could have committed the murder and that Cockrill’s ability to give each of them an alibi is fatally compromised.

The portrayal of Mr Cecil is fascinating. While his effeminate mannerisms are emphasized he is allowed to play a manly part and is there at the death. Cockrill resorts to the tried and tested technique of staging events to make the culprit crack and there is more than a little poignancy in the treatment of Miss Trap, Cecil himself, and even the Rodds. Suffice it to say, this will be Cockrill’s last package holiday, the attractions of a staycation becoming even greater.

Perhaps because I read it immediately after Blake’s working of the theme, I was underwhelmed by the story. It was interesting enough, and the insights into the holidaying Brits were fascinating, but it did not really grab me.

September 14, 2024

The Dementor Wasp

The largest of the 170 or species of the Ampulicidae family, the dementor wasp is native to Thailand, red and black in colour, and the females are about ten millimetres long. They are probably worth avoiding, especially if you are a cockroach.

According to a study published in 2010 in Communicative and Integrative Biology. The wasp injects the brain of its cockroach victim with a toxin that keeps the cockroach alive but in a zombie-like state. The wasp then deposits its eggs into the cockroach’s body and the larvae, when hatched, feed on the victim’s remains.

The wasp was first described by Michael Ohl of the Museum for Naturkunde in Berlin and when the selection of the species name was put to a public vote amongst visitors to the museum, the resemblance to the fictional characters of dementors in the Harry Potter series which are soul-sucking, dark creatures that feed on human happiness, leaving their victims in a vegetative state, was too good an opportunity to miss. And so, the wasp was saddled with the scientific name of Ampulex dementor.

Democracy, eh?

September 13, 2024

The Widow’s Cruise

A review of The Widow’s Cruise by Nicholas Blake – 240810

An artist, especially a sculptor, is trained to observe the physiognomy of their subjects. The trained eye of Clare Massinger, the girlfriend of Nigel Strangeways, makes a telling and ultimately vital contribution to the resolution of the thirteenth novel in Blake’s series, originally published in 1959.

In order to restore her artistic mojo, Nigel suggests that they both go on a cruise on the Menelaos around the Greek islands. Being stuck on board a cruise ship, prison with the option of drowning, allows Blake to assemble a colourful group of characters including a chatty blackmailer, Ivor Bentnick-Jones, a Greek scholar, Jeremy Street, the Bishop of Solway and his wife, and the oleaginous cruise manager, Nikki. However, the disruptive influences and the ones who drive the plot are two sisters, Ianthe Ambrose and Melissa Blaydon, teenage twins, Faith and Peter Trubody, and a 10-year-old girl, Primrose Chalmers, who amuses herself by spying on the passengers and making notes in her journal.

Ostensibly, the Ambrose sisters are chalk and cheese, Melissa a widow and the archetypal femme fatale who has men falling all over her and Ianthe, the highly strung academic and failed teacher who left her last post under a cloud. Ianthe despises Jeremy Street, casting doubts on his scholarship and penning a vitriolic review of his latest work in The Journal of Classical Studies, and, to her horror, she finds that a former pupil, Faith Trubody, whose expulsion she was instrumental in, is on board. Peter Trubody, swears revenge.

There are more than enough people with reason to do away with Ianthe and it comes as no surprise that she goes missing, her body later found by some rocks on the island of Kalymnos and, tragically, the body of little Primrose is found strangled in the ship’s swimming pool. Strangeways, using his status as an adjunct to Scotland Yard, sets out to discover who is responsible for the crimes.

Stylistically, the book falls into two distinct halves. In the first part of the book Blake allows himself the time and space to develop his characters and to explore the tensions that are surfacing aboard the ship. It is beautifully and elegantly written, the author embracing the opportunity to showcase his knowledge of Greek mythology and, as befits a future poet laureate, his encyclopaedic grasp of the poetic canon. The Greek islands he describes are radically different from the austere, brooding, threatening places in Gladys Mitchell’s Come Away, Death (1937).There are some moments of pure comedy, not least the donkey ride.

The second half is radically different, a police procedural with Strangeways conducting interviews with the various characters, trying to piece together what happened on that fatal day and testing the alibis of the prime suspects. In the final chapter, Poirot-like, he calls his suspects together and proceeds to air several theories as to what happened in an attempt to increase the pressure on the culprit so that they ultimately crack and end their life in dramatic fashion. There is little doubt that this is meant to be a parody of the famous Belgian’s methods.

It gives the book something of an ill-fitting feel about it. The mystery is well clued, in fact you could argue that the solution is telegraphed well in advance of the denouement, even if the ending has the power to shock and astound. Far from Blake’s best, it is still an enjoyable and satisfying read with enough twists and turns to maintain the reader’s interest. The relationship between Strangeways and Massinger is blossoming. Never underestimate the power of an artist’s eye.

September 12, 2024

It’s The Way I Tell ‘Em (37)

More of the best one liners (allegedly) from the Edinburgh Fringe 2024:

The conspiracy theory about the moon being made of cheese was started by the hallouminati. – Olaf Falafel

I’m an extremely emotionally needy non-binary person: my pronouns are ‘there there’. – Sarah Keyworth

I’ve got a girlfriend who never stops whining. I wish I’d never bought her that vineyard – Roger Swift

Gay people are very bad at maths. We don’t naturally multiply. – Lou Wall

Growing up rich is a hereditary condition. It affects 1% of people – Olga Koch

September 11, 2024

Scrotum Humanum Revisited

The misidentification of a fossilized femur in Richard Brookes’ book, A New and Accurate System of Natural History (1763), as a human scrotum was to have enormous repercussions in the world of paleontology.

The French philosopher and naturalist, Jean-Baptiste Robinet, included an illustration of the fossil in his Considerations philosophiques de la gradiation nturelle des forms (1768) which was clearly drawn from that in Brookes’ book but went further by claiming to be able to identify the musculature in each “testicle pouch” and that the central cavity resembled a urethra. He discounted the idea that the fossil was the petrified bone of a once-living creature, advancing the theory that it was a stand-alone entity created by mineral germs which happened to resemble a male anatomical part. Robinet’s theory was not widely accepted.

In 1824 William Buckland described “an enormous fossil…reptile” in Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield, which had been discovered in the slate near the Oxfordshire village. He thought it was “an amphibious animal”, not unsurprisingly as previously discovered fossilized specimens unearthed, including Mary Anning’s Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus and Georges Cuvier’s giant monitor lizard found in Masstricht, were clearly water-dwelling. What Buckland called a Megalosaurus, “great lizard”, is known today as a six-meter long land-dwelling carnivore, a femur from which was Brookes’ Scrotum humanum.

In 1827 Gideon Mantell gave the remains the type species of Megalosaurus bucklandii in recognition of Buckland’s part in bringing it to the attention of the scientific community and Richard Owen in 1842 used Megalosaurus as one of the genera that defined the group Dinosauria. By this time the more perceptive minds began to realise that these creatures were a distinct form of animal rather than just a type of big lizard.

However, this thought posed a significant taxonomical dilemma. Under the Linnaean system the first name given to a specimen has taxonomic priority over later names and, inescapably, not only was Scrotum humanum a valid binomen but it was also the first generic and specific name applied to a non-avian dinosaur. In other words, Scrotum humanum had priority over Megalosaurus bucklandii and future generations of paleontologists were stuck with the uncomfortable fact.

The question of what to do about it rumbled on well into the late twentieth century, even though Brookes had known perfectly well that the Cornish femur was not a petrified scrotum and that the rubric to the illustration was erroneous. However, as the term Scrotum humanum had not been used in scientific literature since 1899, under the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) it could be termed a nomen oblatum or forgotten name and its priority dropped, a decision described at the time as “perhaps fortunate”.

In 1985, though, the ICZN dropped the nomen oblatum clause and a paleologist by the name of William Serjeant had to make a formal application for the name to be suppressed so that it would not take priority over a name deemed to be more appropriate.

As to the original fossil that caused all the fuss, it disappeared without trace, possibly shortly after Post had written about it. It is unlikely that Brookes and certainly not Robinet had ever seen it.