Martin Fone's Blog, page 39

October 3, 2024

The Limerick

Outside Limerick’s oldest bar, the White House in O’Connell Street, there is a plaque whose inscription reads: “The Limerick is furtive and mean;/ you must keep her in close quarantine,/ or she sneaks up to the slums/ and promptly becomes/ disorderly, drunk and obscene”. With its five line stanza and an AABBA rhyming scheme it is immediately recognizable as a form of poetry that is synonymous with the Irish city.

However, there are examples of what we now know as the limerick form well before the Irish appropriated it. One of the earliest was written by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, a Latin devotional prayer using the AABBA rhyming scheme, while Iago’s drinking song, the Canakin clink drinking song, found in Shakespeare’s Othello Act 2, Scene 3 (1603) is another. The writer whose name is indelibly associated with the genre is Edward Lear, whose The Book of Nonsense (1846) charmed its readers, young and old, with a collection of humorous five-lined poems.

Lear went a long way towards establishing the normal format of a limerick with the first, second, and fifth lines consisting of three feet of three syllables and sharing the same rhyme, while the third and fourth lines are shorter, consisting of two feet of three syllables with their own rhyme. The first American examples appeared in Charles Leland’s Ye Book of Copperheads (1863). Neither Lear nor Leland, though, called them limericks.

Limericks seem to have been sung to a popular tune, Will You come up to Limerick?, suggested by a newspaper article from St John in New Brunswick in 1880 as the perfect accompaniment to a five line poem using the AABBA rhyming scheme it had printed. However, it was not until May 1896 that anyone consciously called the poems limericks, Aubrey Beardsley writing in a letter that “I have tried to amuse myself writing limericks about my troubles”.

Beardsley’s use of the term was the culmination of the campaign waged by the Irish Literary Revival, led by W B Yeats and George Sigerson, to promote the claims of the 18th-century Maigue Poets, Seán O Tuama and Aindrias MacCraith, rather than Edward Lear as the true proponents of the poetic form. As the poets came from Croom in Co Limerick, the revivalists called their poems “limericks”, a term the British initially reserved for the more risqué versions of the poem. In turn, Fr Russell, editor of The Irish Monthly, coined the word “learic” to denote the cleaner versions.

For the British public, though, such pedantic nitpicking was too abstruse and “limerick” stuck.

October 2, 2024

Death Croons The Blues

A review of Death Croons the Blues by James Ronald – 240828

The seventh in the series of James Ronald collections reissued by Moonstone Press features a novel, Death Croons the Blues, originally published in 1934, a novella, Angel Face, and two short stories, The Other Mr Marquis and The Joke. Both the novel and novella feature what comes close to a series sleuth, the journalist with a nose for a story and trouble that is Julian Mendoza, whose unorthodox methods always put him one step ahead of Inspector Howell of the Yard.

Like Farjeon’s Seven Dead, Death Croons the Blues starts off with a burglar, Bill Cuffy, getting more than he bargained for when he breaks into the flat of blues singer Adele Valée as he stumbles on her body. She has been brutally murdered with a kukri, a Gurkha knife. He flees in terror and finds himself in Mendoza’s lodging house and in the metaphorical arms of his landlady, the formidable Mrs MacDougal. Despite Cuffy’s unlikely story, Mendoza believes that he did not kill the singer and, sensing a scoop, sets out to investigate.

It is an action packed story told at a breathless pace, taking Mendoza both into the demi-monde where he has a violent confrontation with an ex-professional boxer, Tiger Slavin, and the upper echelons of society, including a former Cabinet minister. There is blackmail, the set up of an impecunious member of the aristocracy, a couple of hard luck stories amongst the lower orders who see the opportunity to better themselves, and more than one seemingly unshakeable alibi.

Rather like Christie’s later Cards on the Table the breaking of an alibi centres around the playing style of participants in a game of bridge. One player takes an inordinate amount of time to play their hand when leading, allowing the dummy more than enough time to commit their foul deed. The other give away is that they wear a tie so out of kilter with the rest of their evening wear. The murder is meticulously planned, but requires such precise timing and for everything to go as planned that it verges on the incredulous.

Mendoza is a rough diamond, good company and ruthless in his determination to bot solve the crime and get a scoop for his newspaper. This determination endangers the lives of several of the characters and infuriates Inspector Howell who is bound by the rules of police engagement and cannot compete with the journalist’s unorthodoxy. But Mendoza’s methods produce results, revealing a surprising twist involving the back story of Adele Valée and bringing happiness to some poor souls who desperately need it.

The other star of the story is the formidable Mrs MacDougal, who is roped in by her tenant to help out. The opening scene with Bill Cuffy is very amusing, but she also has a softer side, revealed when she deals with an aggressive and unpleasant landlady who threatens to evict an ailing Mrs Cuffy. She is great value.

Angel Face takes into Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock territory with razor gangs controlling racing and dog tracks and the ambitions of a Mr Big to take over all the protection rackets in the capital. This is even faster moving and Mendoza is a man on a mission who takes more than enough beatings in his pursuit for the identity of the master puppeteer. His methods are highly unorthodox, combating American-style gangsterism with American-style policing, once more leaving Inspector Howell aghast, but they prove effective when the weak link is identified. This is a pot-boiler of a thriller as the mystery is drained out of the story by Ronald’s surprising decision to reveal the identity of the ring leader so early on.

The Other Mr Marquis is a study of paranoia which has gripped a bibliophile while The Joke is a mildly amusing extension of the idea that twins experience and suffer the same sensations as each other. I have enjoyed discovering James Ronald and Moonstone Press are to be commended for bringing some of his work back for a modern audience to explore.

October 1, 2024

Twain And The International Date Line

On October 1, 1884, forty-one delegates from 25 nations assembled at the Diplomatic Hall in Washington D.C at the invitation of the US President, Chester Arthur, their mission to establish the Prime Meridian. As it travels around the Sun the Earth rotates on its axis in a counterclockwise direction (from west to east), meaning that different parts of the globe receive the Sun’s direct rays at different times. The boom in global commerce, the growing interdependency between nations, and the increasing sophistication of communications systems meant that it was imperative that all clocks were set to a world standard.

The delegates voted by 22 votes to one to accept the meridian passing through the Observatory at Greenwich as the Prime Meridian from which all longitudes would be calculated both east and west until the 180⁰ meridian was reached. There would be twenty-four time zones of 15 degrees each, twelve running eastwards from the Greenwich meridian to the 180⁰ point and twelve westwards. All countries would adopt a universal day, lasting twenty-four hours, beginning at midnight in Greenwich and counted on a 24-hour clock.

San Domingo, now Dominican Republic, voted against Greenwich being the Prime Meridian with Brazil and France abstaining, the latter not adopting the Greenwich meridian on their maps until 1911.

The conference also selected the 180⁰ meridian as the location for the International Date Line (IDL), marking the boundary between one calendar day and the next, passing through the sparsely populated Central Pacific Ocean and causing, at least to western eyes, least inconvenience. Crossing the IDL eastwards decreases the date by one while crossing it westwards advances it by one. Never defined in international law, it runs an erratic path on a map, as countries through whose waters it passes have moved it for their convenience.

One of the most recent examples was Samoa which effectively erased December 30, 2011 from the country’s calendar when it crossed westwards over the IDL. Crowds gathered around the main clock tower in the capital, Appia, and cheered as the clock struck midnight on December 29th, instantly transporting them to New Year’s Eve. Geographical proximity creates some oddities. Just two miles of the Bering Sea separate Big Diomede Island, part of Russia, from Little Diomede, part of the US, as the IDL passes between the two, the Russian territory is always one day ahead.

For sailors and passengers alike crossing the IDL was a high water mark in a voyage across the expanse of the Pacific Ocean. One to experience the sensation was Mark Twain who in 1895 was travelling on the SS Warrimoo, sailing from Vancouver to Sydney, at the start of a world lecture tour to restore his finances after an unwise investment. In Following the Equator (1897) he described the moment, characteristically pointing out the absurdities that arose.

“While we were crossing the 180th meridian”, he wrote, “it was Sunday in the stern of the ship where my family were, and Tuesday on the bow where I was. They were there eating half of a fresh apple on the 8th, and I was at the same time eating the other half of it on the 10th – and I could notice how stale it was, already”.

A child was born in steerage at the precise moment, he reported, and there was no way to tell which day it was born on. “The nurse thinks it was Sunday, the surgeon thinks it is Tuesday”. Twain feared for the child’s future, surmising that the doubts as to its birth date will lead to “vacillation and uncertainty in its opinions about religion and politics, and business, and sweethearts” making it characterless and impossible for it to make a success in life.

September 30, 2024

Seven Dead

A review of Seven Dead by J Jefferson Farjeon – 240824

There is nothing worse when you are going about a bit of honest house breaking than finding a room with seven dead bodies, six men and a female dressed in mannish clothing. This is what confronts Ted Lyte at Haven House in the dramatic opening to Jefferson Farjeon’s second and final book in his Inspector Kendall series, originally published in 1939 and reissued as part of the British Library Crime Classics series.

When the police visit the scene, they find a note welcoming them to the Suicide Club on one side and with a code, which even the most land locked landlubber can recognize as geographical co-ordinates although it takes them some time to realise it, written with a red stubby pencil. The clock in the centre of the mantlepiece has been moved and in its place is a vase with an old cricket ball on top. Throw in a couple of dead cats and no obvious sign as to how all the victims met their end and a painting of a young girl in another room with a bullet hole through her image and you have the makings of a mystery that will test the mettle of even the best detective.

Inspector Kendall seems to be bedevilled by journalists. Having had to contend with Bultin in Thirteen Guests he now has to deal with Tom Hazeldean, whom at least he sees as a useful idiot. As well as being willing and intrigued by the case ever since Ted Lyte ran into him, he is besotted with the image of the girl and has a yacht which makes it handy for a jaunt to Boulogne where the girl in the image, Dora Fenner, niece of the owner of the doomed house, is believed to have fled for unspecified reasons. Hazeldean volunteers to handle that aspect of the case and Kendall is more than happy to have him out of the way so that he can concentrate on matters at the British end.

The focus of the book then turns to Hazeldean’s adventures sur le continent where he easily, conveniently too easily, tracks down the girl, wins her confidence and then is introduced to a strange pension where her uncle, Fenner, double crosses him and the pension owner, Mr Jones, is killed in a plane crash and the silk merchant who has been trailing Hazeldean is murdered. Back in Blighty Kendall uncovers more disparate clues including a missing bicycle, a hidden laboratory, and an abandoned lifeboat from an ocean liner before moving to Boulogne to extract Hazeldean from his difficulties.

There is then a jump in time before the next part of the story when Kendall joins forces with Hazeldean and his now wife, Dora, to sail to the point designated by the co-ordinates, an isolated island in the South Atlantic. It ultimately boils down to a tale of a man who has three identities, a group who swear to wreak their revenge on someone who has double crossed them in a moment of extreme peril, and a desperate attempt to eliminate all traces of previous misdemeanours and scoop the ultimate prize of profits from a deadly poisonous gas, the efficacy o which is only too apparent.

While the narrative is bitty it is fast paced and all the disparate pieces, including the obsession over cricket, come together when a diary is found on the deserted island. Farjeon wisely eschews the tedium of interrogations, concentrating on action while delivering the necessary information as the storyline demands. While it does not emulate the drama of its opening, it is a readable and enjoyable piece of crime fiction.

September 28, 2024

Some Rochdale Pioneers

One of the many problems that the Rochdale Pioneers faced before being able to open their shop at Toad Lane on December 21, 1844, was the supply of produce. Determined to stifle this piece of working class initiative local politicians and businessman pressurised local businesses to have nothing to do with them, forcing the Pioneers to travel as far as Manchester, some ten miles away, to get supplies. The barrow was borrowed by John Hill and pushed by Samuel Ashworth, William Cooper, and John Holt.

The honour of opening the shutters of the shop for the first time fell to James Smithies. He was to play a prominent role in the Pioneers, developing strategies to buy and store produce in large quantities, improving the efficiency of transporting goods, and organizing the store into logical departments. Smithies was also active in teaching members and others to read and write.

In the Toad Lane store James Standing weighed the produce, using accurate scales – this was not always the case in shops in those days – and ensuring that the amount was as requested and that the produce was unadulterated. He became an active campaigner in support of The Ten Hour Act, a bill designed to reduce the length of the working day to a maximum of ten hours. This was introduced, as part of The Factories Act, in 1847.

Like Smithies many of the original Pioneers had deeply held political convictions around the need to develop a better society, and were socialists and chartists. The Pioneer Society’s principle of one member, one vote went to the heart of Chartist aspirations. Some also had strong religious beliefs. James Wilkinson would walk across the moors, regardless of the weather, preaching the gospel to congregations in Todmorden, Bacup, and other surrounding towns, and founded a church in Rochdale, known as the co-op chapel because the congregation included fourteen Pioneers.

John Scowcroft, a rag and bone man rather than a weaver or artisan, would also walk the moors spreading the gospel, usually around the Ramsbottom area. He took grave offence when other Pioneers sought to stifle discussion of religion at their meetings.

The early days of the store at Toad Lane were a struggle and money was tight, Samuel Ashworth and William Cooper working initially for free until the Pioneers had built up enough money to pay them. They also took loans from Benjamin Rudman who did not require security nor bother even giving them receipts, trusting them implicitly to make good their debts in due course.

The success of the Pioneers led to a significant expansion in the range of their activities. The Co-operative Wholesale Society (CWS), the Co-operative Insurance Society, and the Co-op News were set up by Abraham Greenwood. The CWS went on to supply goods all around the world under the guidance of John Thomas Mitchell, earning him the sobriquet of “Baron Wholesale”.

There is a trail around Rochdale Cemetery which links seventeen graves, fifteen of which are from the originals and the other two from early members.

September 27, 2024

Trent’s Last Case

A review of Trent’s Last Case by E C Bentley – 240822

One of the three best detective stories ever written, according to Agatha Christie, and one to which every detective writer owes something, consciously or subconsciously in Dorothy L Sayers’ opinion, Trent’s Last Case, originally published in 1913 and also known as The Woman in Black, holds an iconic status in the development of the genre. Curiously, Edmund Bentley today is perhaps better known for inventing the clerihew, an irregular form of humorous verse on biographical topics which bear his middle name.

It is always difficult from this distance to get a sense of what the contemporary reader would have found groundbreaking in Bentley’s approach and to assess its impact. For me the surprise came when John Marlowe looks in the car rear view mirror and sees the look on Sigsbee Manderson’s face and realizes that he has been set up. A little research led to my discovering that that standard piece of motoring equipment and the bane of the learner driver’s life was not patented until the early 1920s and was a very unusual feature, although one that a plutocrat might have installed.

Probably what was really intended to shock and surprise is that what seemed a logical solution to the mystery of Manderson’s death, pieced together from disparate clues ranging from the state of the victim’s clothing and, particularly, his shoes – Manderson had a bit of a shoe fetish – to the fact that he went out without his dentures by the amateur sleuth, Philip Trent and revealed halfway through the book, is only part of the answer. Two more layers of complexity are added to Trent’s foundations as the book progresses, both by way of confessions, the last intended to be quite a twist and a shock.

Perhaps because I have read so many stories where the initial theory proves to be inadequate, becoming one of Sayers’ subconscious borrowings, it did not seem to have the same powerful effect that it must have had when it was originally published. The impact was further diluted by the fact that I had already got the real agent of Manderson’s death in my sights. The denouement, though, was so devastating to Trent that he vowed to give up sleuthing for good, hence the book’s title.

In her review, Kate Jackson floats the idea that Bentley might have had in mind a satire of the nascent genre and I have some sympathy with that reading of the novel. Bentley was trying to get away from the omniscient supersleuth that the likes of Conan Doyle had created, preferring a character who was human with human fallibilities, so much so that they doubt their abilities and retire gracefully. He did not return to Trent for another twenty-three years, which suggests that he had done with the genre by pointing out some of its absurdities.

Manderson is the archetypal villainous victim over whom the reader is invited to share little sympathy and the first chapter which goes to great lengths to establish his status in the financial world, his ruthless methods and the imminence of a shock on the stock exchange to lull the reader to thinking that his death is business related. However, as Trent quickly establishes, the real root of the mystery lies in his fractured relationship with his wife, Mabel, and his suspicions of a love triangle. Trent is so taken by the image of the widow dressed in black, sitting on a rock, that he becomes besotted with her and allows his feelings to cloud his judgment.

It is a case where the sleuth decides to suppress the truth and one in which the police, led by Inspector Murch of the Yard, fail to get anywhere near the solution, allowing Trent to play judge and jury, another trope that was to find favour with later crime writers. Bentley’s style is a little wordy but there is a sense of pace to the story, except for a curious and overlong chapter where Trent broods over Mabel that a more brutal editor would have excised, and on the whole makes for a satisfying read. However, from this time perspective it lacks the wow factor that it once undoubtedly had.

September 26, 2024

Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers

It was grim up North, especially in the mid-19th century. Factories were dangerous places and the work, as well as tedious and gruelling, was unrelenting with 12 to 14 hour shifts six days a week, even for children. The long working days also meant that by the time the workers left the factory most of the shops had closed, leaving them at the mercy of company-owned stores where prices were set artificially high. Even the food they bought was of low quality and often adulterated and in short measure.

A group of workers in Rochdale, calling themselves the Pioneers, decided that things had to change and proposed the establishment of a store that would not only sell pure and unadulterated foodstuffs at a fair price and in the advertised weights but also to operate on democratic principles. The management would be elected by the members and decisions would be decided by a majority vote with every member, whether male or female, having one vote each. Anyone spending in the store would also receive a share of the profits and the more they spent, the higher their return, extending the concept introduced by the Fenwick Weavers’ Society and a predecessor of the Co-operative “divi”.

The Pioneers set out their guiding principles which included open membership, democracy, dividend on surplus in proportion to trade and capital, limited interest on capital, political and religious neutrality, cash trading with no credit extended (unlike the Fenwick Weavers), and promotion of education. Share capital was raised and the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers was born, one of the first consumer co-operatives in the world. Some authorities report that there were twenty-eight original members who each subscribed £1 but neither the total of the capital nor the number of members appears in the co-operative’s minutes.

Fine aspirations are one thing but putting them into practice was another. Initially, they met a lot of resistance from local landlords and traders, having trouble getting a lease on a suitable property. Eventually, having raised £10 to rent premises at Toad Lane in Rochdale. Even then the gas company was reluctant to connect them to the services. Eventually, on December 21, 1844, they were able to open their shutters and start trading.

However, local wholesalers were determined to stifle this innovative competition and refused to provide the Pioneers with stock, forcing them to obtain the initial supplies of butter, sugar, eggs, flour, and oatmeal from Manchester. This involved wheeling the stock in a wheelbarrow for ten miles, a journey that took at least four hours.

Nevertheless, despite all the obstacles, the Pioneers soon gained a reputation for providing high-quality and unadulterated goods and within three months had expanded the range of items for sale to include tobacco and tea. By the end of the first year of trading, they had expanded to eighty members and had capital of £182. The co-operative movement was born.

The Rochdale Pioneers Museum marks their achievement and is well worth a visit. Next time we will look at some of the prime movers of the Pioneers, many of whom are buried in the local cemetery.

September 25, 2024

Your Country Needs You

Perhaps the greatest contribution of the weekly magazine, London Opinion and Today, to British culture was the front cover of its issue for September 5, 1914. By this time it was known for its black and white cartoons, it did not introduce colour until the1920s, and had a circulation of around 300,000. The cover bore a striking image of Lord Horatio Kitchener staring and pointing with the rubric “Your Country Needs You”.

It was the handiwork of Alfred Leete, originally a printer from Weston-super-Mar, who switched to drawing cartoons when Punch accepted one of his drawings in 1905. As a cartoonist he was well versed in the need to get a message across succinctly and with power. Kitchener’s eyes, rather like those of the Mona Lisa, stare out and seem to follow the viewer. Photoshopping is not a modern phenomenon and Leete was not averse to manipulating the image of Kitchener who, by this time, was 64 years old, by darkening and widening his moustache and correcting his squint.

The stroke of genius, though, was Kitchener’s hand gesture, provocatively direct and demanding a response from the viewer. Inside the same edition Leete had a half page cartoon showing a uniformed soldier with a girl on each arm, viewed with jealousy by a wimpish young man in civilian garb. The message was clear, if unsubtle: only the volunteer for Kitchener’s Army gets the girls.

Leete’s designed was copied for military recruitment campaigns from India to Canada and Germany while four million copies of James Montgomery Flagg’s Uncle Sam take of the image were printed in the US during the First World War. Unprotected by copyright it has been used for humorous effect on a multitude of items and has proven to be universally popular, iconic and ageless, a graphic designer’s dream.

According to James Taylor in his book Your Country Needs You (2013), though, after trawling through the records of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, there were almost 200 official recruitment posters produced during the First World War but the iconic “Your Country Needs You” poster was not one of them. His analysis of thousands of photographs of street scenes and recruiting offices failed to reveal it and while the London Opinion offered its readers 100 postcards of the image for 1s 4d, Taylor could not track down any surviving examples.

The wording did appear in poster form was an elaborate design, when the words and picture appear, in a smaller scale, below five flags and surrounded by details or rates of pay and other information, including the additional slogan – “Your Country is Still Calling. Fighting Men! Fall In!!”. Taylor found no evidence it was particularly widespread or popular at the time. However, the most popular poster of the era, in terms of numbers produced, did feature Kitchener, but without the pointing finger and featuring a 30-word extract from a speech he had made.

Leete’s image only became iconic after the First World War, and the idea that it inspired thousands of men to join up ahead of conscription seems like an urban myth.

September 24, 2024

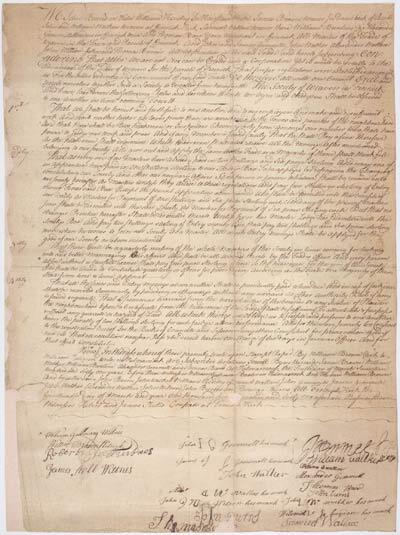

The Fenwick Weavers’ Society

Sixteen weavers met at Fenwick Church near Kilmarnock on March 14, 1761, to put in motion a revolutionary idea. Instead of relying upon the patronage of the local landowners and aristocracy, they were looking to organize themselves and co-operate with each other in a way that was mutually beneficial. They signed the foundation document of the Fenwick Weavers’ Society, agreeing to be “honest and faithful to one another” and their employers, making “good sufficient” work, and setting prices that were “neither higher nor lower…than are accustomed in towns and parishes of the neighbourhood”. They agreed to pay an admission fee of two shillings and sixpence to be used for the good of the Society.

Initially, the Society began by sharing equipment that were used within the weaving industry such as looms and raw materials but by November 1769, it was looking to provide benefit to the wider community. It used its funds to buy food in bulk to get the advantage of the lower wholesale prices and then sold off smaller portions to members and non-members alike at a cost above the wholesale price but below the commercial cost. The profits were then divided amongst its members, a redistribution model thought to have been a precursor of the dividend model later by the later co-operative movement.

The Fenwick Weavers’ Society gradually extended its range of activities, lending small amounts of money to families of its members, acting, effectively, as an early form of credit union, founding a subscription library in 1808 and setting up an “emigration society” which facilitated locals to emigrate to Anglophone countries such as New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and the United States.

By 1873, the emigration programme had proven to be something of an own goal with the population of Fenwick dropping to a quarter of its original 2,000, causing the Society to disband. It was reconvened in March 2008 as an industrial and provident society with a mission to record, collect, and commemorate the history and heritage of the Weavers.

Today, there are over three million co-operatives world-wide with over one billion members and employing, directly or indirectly, 250 million people. The germ of the idea formulated by the Fenwick Weavers Society was developed upon by the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, who are widely considered to be one of the very first consumer co-operatives. We will chart their story next time.

September 23, 2024

Murder By Chance

A review of Murder by Chance by Peter Drax – 240819

Eric Addis, writing under his nom de plume of Peter Drax, published six novels, the first of which, Murder By Chance, was originally released in 1933 and has subsequently been reissued by Dean Street Press. His aim was to add a touch of realism to the cosy genre of detective fiction and, if this book is anything to go by, he succeeded. This is more a thriller than a murder mystery, the identity of the murderers – there are two corpses – revealed to the reader as they happen, and it is a page-turning and gripping read.

There is no mastermind who has planned the perfect crime. We have a group of chancers who spot an opportunity and go for it but their plans quickly unravel as events and pure chance intervene reducing their chances of success. On the side of law and order there is no brilliant sleuth who is able to reconstruct the crimes and identify the culprits from the slightest of evidence. Chief Inspector Thompson is hard working and diligent but at the end is no nearer identifying the suspect whom he has dubbed X let alone get his hands on them. It takes the dramatic intervention of a Royal Navy destroyer to thwart an audacious escape, but the culprits swap the hemp jig for Davey Jones’ locker.

One of the fascinating aspects of the book for me is that it shines a light on a part of riparian London that, thanks to the increase in the size of shipping using the dockyards in London and the combined effects of the bombing raids of the Luftwaffe and the subsequent gentrification of the area, no longer exists. It is full of picaresque characters, living on the extremities of society, eking out a living any way that they can. There is grime and dirt, squalor but also a sense of camaraderie, at least at the very bottom of the pile.

The original crime is as old as the hills or, at least, as old as mercantile trading, buying a ship and scuttling it to obtain the insurance money. Johannis Kurdorfer is a master of this form of insurance fraud, able to see out a comfortable retirement on his Mediterranean island of Posnik, having earned such a notoriety that the underwriters and brokers have refused to have anything to do with any risk that he is remotely involved in. Oh for the days before anti-collusion laws. The underwriter’s life would be much simpler.

However, Kurdorfer is bored and is easily lured out of retirement by Sam Hartford who proposes to buy an old ship, the Karnoc, and, with his help, scuttle it. As Kurdorfer is blacklisted at Lloyd’s, another captain is hired, Geoffrey Hunt, whom Kurdorfer instantly dislikes. Alfred Brown is involved in the scheme to raise the purchase money but, seeing his main chance, looks to double-cross Sam but his plans to raise the money meet with unexpected difficulties. Before they even get their hands on the Karnoc, two men are murdered, Hunt and Hartford.

The plot is clunky at times and requires some unlikely coincidences to occur, but what Drax lacks in finesse in that department, he more than makes up for in excitement and there is an urgency to his style. Contrary to the impression gained from detective fiction, murders are rarely premeditated but are more often the unanticipated consequences of a nexus of circumstances. Drax’s novel approach makes a refreshing change and it is fascinating to see how the characters react to the predicament they find themselves in.

If you want a different perspective on the detective fiction genre, this is a must-read. I look forward to following the series.