Martin Fone's Blog, page 314

October 27, 2016

Double Your Money – Part Ten

John Sadlier (1813 – 1856)

Dickens’ Mr Merdle (Little Dorrit) and Trollope’s Augustus Melmotte (The Way We Live Now) are larger than life literary characters, the epitome of all that was wrong and evil with the Victorian capitalist system. There is little doubt that these characters were based on John Sadlier, an Irish financier and Member of Parliament, dubbed by the contemporary press as the Prince of Swindlers when his peculations were unearthed.

Although he started his working career as a solicitor in Dublin, he founded the Tipperary Joint Stock bank with his uncle, James Scully, in 1838, offering above average interest rates to small farmers and tradesmen. The bank prospered. In 1847 Sadlier was elected member of parliament for Carlow and on moving to London was appointed chairman of the London County Joint Stock Banking Company the following year. It was from this base that he began his investment career, financing railway developments in Sweden, France and Italy, founding his own Dublin newspaper, the Weekly Telegraph and buying swathes of land, valued at over £250 million.

Sadlier seemed to have the Midas touch and quickly became a household name as the Warren Buffett of his era. He couldn’t fail and returned dividends of 6%, significantly higher than his competitors, to his delighted shareholders. In parliament he led what was known as the Pope’s Brass Band, a group of MPs who resisted the Liberal government’s attempt to restructure the Catholic Church, founded the Catholic Defence Association and in late 1852 became Junior Lord of the Treasury.

But like Midas, he was doomed. Not everything was at it seemed. The high dividends were only payable because of fraudulent book-keeping and over-valuation of assets. In 1853 Sadlier was forced to resign his parliamentary seat when an investigation into his election campaign of 1852 showed that the financier had used his bank to bring pressure to bear on 208 voters in the Carlow constituency.

Sadlier started to make increasingly reckless investments, borrowing heavily from his own bank, forging shares in the Royal Swedish Railway Company of which he was chairman and rather desperately and unsuccessfully sought the hand of any Catholic heiress that had enough dosh to get him out of his difficulties. By February 13th 1856 the writing was on the wall. The London agents of the Tipperary Bank refused to cash drafts that Sadlier sent him. The following weekend he wrote a despairing letter to a cousin in which he confessed to “numberless crimes of a diabolical nature” causing “ruin and misery and disgrace to thousands – ay, tens of thousands”.

On the night of February 16th he went to Hampstead heath and behind Jack Straw’s Castle took prussic acid from a silver cream jug – Melmotte’s chosen form of suicide – and was found the next day. Sadlier may have escaped justice but his peculations left many ruined. His overdraft was £250,000 and his collapsed banking empire owed the Bank of Ireland £122,000. He had defrauded the Royal Swedish Railway Company to the tune of £300,000. Over £400,000 was lost by depositors – an enormous sum given that the total deposits of all the joint stock banks in Ireland at the time was £12 million.

Sadlier’s brother, James, an MP at the time, also put his hand in the till and upon his brother’s death scarpered, ultimately to Paris where he was spotted and ordered to return to Westminster. He refused to attend and was expelled – the first MP to suffer this fate in half a century. James eventually settled in Zurich and in June 1881 he was set upon by a knife wielding man who stabbed him to death. Whether the assassin was a creditor with a long memory is not certain.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: Augustus Melmotte, Jack Straw's Castle, John Sadlier MP, Little Dorrit, London and County Joint Stock Banking Company, Mr Merdle, Pope's Brass Band, The Prince of Swindlers, The Way We Live Now, Tipperary Joint Stock Bank

October 26, 2016

Book Corner – October 2016 (2)

The Long Weekend: Life in a Country House between the wars – Adrian Tinniswood

Depending upon your point of view, English country houses were the glue that held rural life together and provided employment to the lower orders or they were the embodiment of the class system that bedevilled British society. Or you could be like Sir Charles Trevelyan and try to have your Victoria sponge and eat it – he moved into Wallington House in Northumberland in 1929 and started opening it up for community events of a socialist hue before eventually giving it over to the National Trust in 1936 on the proviso that he could continue to live there. “I do not believe in the private ownership of land”, he said. “By pure chance I own Wallington. I regard myself solely as a trustee for the community..”

The Long Weekend is the period between the end of the First World War and the start of the Second, a period of phenomenal change and challenge for the country house, beloved of English fiction of all genres in the early to mid 20th century and TV series to the current day. The carnage of the Flanders’ killing fields did for many a son and heir as well as cutting down swathes of erstwhile servants and estate workers. Taxes and death duties were crippling. Some chose to sit it out, immolated in grief, hanging on in quiet desperation, the English way, like the first family we meet, the Hoares of the wonderful Stourhead whose son, Harry, was killed in 1917, until death and the National Trust came knocking on the door as they did in 1946.

But it was not all gloom and doom. Often salvation came from across the pond either through judicious marriages with American heiresses a la Lord Grantham or through monied American purchasers. The newspaper tycoon, Randolph Hearst, telegraphed “want to buy castle in England, please find one which ones available”. He ended up with St Donat’s which happens to be in Wales, a small detail perhaps. Others were remodelled, some more sensitively and successfully than others, to introduce some of the modern conveniences that earlier owners thought unnecessary, like electricity. The castles at Leeds, Herstmonceaux and Saltwood were all restored during the twenties and thirties.

Some were built from scratch – Lutyens built Castle Drogo for Julius Drewe who wanted a new mediaeval castle built, a contradiction in terms which seemed to escape him. But others were pillaged, staircases and ceilings shipped off to America and some like Nuthall temple in Nottinghamshire demolished. Many didn’t survive the Second World War, not because of bombing but because of the vandalism of troops who were billeted in the stately piles.

Tinniswood is a fount of amusing stories, enlivening the account of life both above and below stairs. I particularly enjoyed the chapter on Saturday to Monday parties – it was infra-dig to call them weekend parties. So accustomed were the staff to see priapic male guests padding the corridors en route to an illicit assignation that one poor chambermaid turned a blind eye to one who turned out to be a thief making off with jewellery to the value of £4,000.

I found the sections on architectural features harder going and, perhaps, more illustrations would have helped the reader. But on the whole it is an engaging and entertaining book with a fund of anecdotes which will light up a dull dinner party. If you haven’t read it, put it on your Christmas list.

Filed under: Books, Culture, History Tagged: Adrian Tinniswood, country houses between the wards, Randolph Hearst, Sir Charles Trevelyan, Stourhead, The Long Weekend

October 25, 2016

On My Doorstep – Part Twelve

The murder of the Reverend Hollest, 1850

Murder most foul was committed in Frimley on 27th September 1850 at around 3 o’clock in the morning. The vicar of Frimley, the Reverend George Hollest and his wife, were lying in their four-poster bed in the Parsonage when they became aware of intruders. According to Mrs Hollest, “we both jumped up in bed at the same time. I saw two men at the foot of our bed”. Both were armed and threatened that “if we made any noise, they would blow our brains out”.

Bizarrely, the Reverend thought that it was their sons who were playing a trick on them, testament to either his unworldliness or his poor parental control. Mrs Hollest was made of sterner stuff and realised that this was indeed a real burglary, tried to summon help by ringing a bell but was pushed to the ground for her troubles. She broke free and managed to raise the alarm, prompting the intruders – there were three indoors and one waiting outside – to flee the scene. By this time the Reverend gave chase, picking up his loaded gun which he kept by the door. Mrs Hollest heard a shot and when her husband returned, he informed her he had been shot in the abdomen. Mrs Hollest summoned the police – Frimley had two parish constables at the time – and the surgeon, Mr Davies.

At first, the vicar was not thought to be seriously injured but his condition soon deteriorated and he died the following evening “after much suffering”. A post mortem revealed a loose marble in the fold of the peritoneum, between the bladder and the rectum. The thieves had got away with quite a haul – they abandoned a telescope and umbrella by a tree in their dash for freedom – including three watches (two gold and one silver), various small silver items, a bag of copper coins from the Parish Clothing Fund and a gold ring set with a bloodstone and on which Forget me not was engraved in old English lettering. A reward of £150 was offered for the arrest of the malefactors.

Three young men of bad character, according to contemporary reports, were arrested in the Rose and Crown beer-shop, Hiram Smith, James Jones and Levi Harwood, and were brought before the deliciously named local magistrate, Captain Mangles. A fourth suspect was added to the group, Samuel Harwood. There being no honour amongst thieves, Smith turned Queen’s evidence. Betraying the physiognomic theories of the time, the Times described him as having a sallow, unhealthy skin, an extremely forbidding expression, prominent features and a hesitating glance that marked him out as a rogue.

According to Smith, the four men had walked to Frimley, armed with two horse pistols which they loaded with marbles. After breaking in to the Parsonage, they feasted on bread, beef, wine and spirits and being satisfied that they were undetected, went up to the Hollest’s bedroom, Samuel Harwood, who was unmasked, waiting outside. Witnesses identified Smith as having been in Frimley some days earlier, selling earthenware, presumably on a recce. One of the coins from the Clothing Fund which was badly worn was found on one of the burglars, was recognised by Mrs Hollest.

Levi Harwood, who confessed to the murder, and James Jones were sentenced to hang on 15th April 1851, Levi Smith was cleared of murder but detained and brought to trial for another robbery – he cheekily claimed the reward but there is no record of him being paid – and Samuel Harwood was released through lack of evidence. One consequence of the murder was that Surrey got its own county constabulary. The parsonage was sold shortly afterwards and today is a convent.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: Levi Smith, murder most foul in Frimley, murder of Reverend Hollest, Reverend Hollest, the Parsonage at Frimley

October 24, 2016

A Better Life

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearance

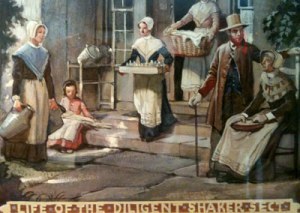

When all around you is going from bad to worse there is something vaguely appealing about starting again from scratch and creating a society which operates in the way you think best, in other words a utopian society, a term first coined by Thomas More in his book, Utopia, published in 1516. One of the most successful utopian communities, at least in terms of longevity, was the United Society, better known as the Shakers.

In the 1760s there was an offshoot of the Quakers operating in England, called the Shaking Quakers, so-called because they danced and spoke in tongues. By 1770 Ann Lee had split from the Quakers following the death of her fourth child and formed the Shakers, claiming to have had a vision from God in which she was told that sexual intercourse was the root of all evil and that to truly follow God you had to be celibate. Perhaps a more revolutionary thought was that God must be bisexual because both men and women were made in God’s image.

Lee gathered adherents, who regarded her as the female component of Christ’s spirit and as representing Christ’s second appearance on earth. Mother, as she was known, then had another vision in 1772, in the form of a tree, telling her to move to America where a place had been prepared for the Shakers. So in 1774 nine Shakers, including Lee, upped sticks to cross the Atlantic, stopping initially in the Big Apple while saving up enough money to buy a patch of wilderness they called Niskeyuna in Western New York State, the first of what were to become eighteen Shaker communities.

Four basic tenets ruled the Shaker lifestyle – communal living, celibacy, regular confession of sins and withdrawal from the outside world. Men and women were treated equally and people of different races and creeds were welcomed – truly revolutionary for the time but also sensible because the strict celibacy rule meant that they needed to recruit constantly in order to survive. There was also a strong work ethic, requiring each member of the community to work – each had an allotted task – and they were expected, in the words of Lee, to toil “as if you had 1,000 years to live, and as if you were going to die tomorrow”. Their craft work reflects the pride and care they took in their work.

The Shakers also believed that their communities would serve as a model by which they would attain redemption, a promise which they used to attract the new recruits which were their lifeblood. By 1850 there some 4,000 Shakers in America in communities from Maine to Kentucky – Lee’s last vision told her that they would find an ideal place for their communities out West.

Over the two centuries or so of their existence it is estimated that some 20,000 or so have lived their lives in whole or in part in accordance with the tenets Mother Lee established in accordance with her vision. There are now just a handful of Shakers but they have reason to hope. According to yet another Lee vision – how many can you have? – the community would be renewed when membership had dropped to five. You can imagine the remaining handful anxiously looking for any sign of ill-health amongst their colleagues. Needless to say, it’s not happened yet!

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: Ann "Mother" Lee, Niskeyuna, tenets of Shaker life, the Shakers, The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearance

October 23, 2016

Chilli Of The Week

Although I’m partial to a curry I have never really the understood the attraction of an AB (arse burner). I have never been tempted in the slightest to test my ability to endure a hot chilli. But there are some who can’t resist the challenge and, indeed, enter competitions to demonstrate their bravado. If you are in the slightest bit tempted, here is a cautionary tale I came across this week.

It features the Bhut jolokia aka the ghost pepper which measures 1 million on the scale created by Wilbur Scoville in 1912 to measure the pungency of chillis. To put it into context it is 400 times hotter than Tabasco sauce. Anyway, some herbert, unnamed, in America (natch) smeared the chilli in powdered form on to a burger and proceeded to eat it. No sooner than he had taken the last mouthful, he started experiencing violent retching and severe abdominal and chest pains.

On arrival at the hospital it was discovered that the chilli had made a 2.5-centimetre tear in his oesophagus. The result – 23 days in hospital and a gastric tube fitted on discharge.

A warning to us all. Mind you, the Buht jolokia is nothing compared to the world’s hottest, the Carolina Reaper, which weighs in at 2.2 million Scovilles.

Filed under: Humour, News Tagged: Bhut jolokia chilli, Carolina Reaper chilli, man tears oesophagus after eating chilli, the Scoville scale, Wilbur Scoville

October 22, 2016

Fountain Of The Week

I’m partial to the odd glass of vino and so my ears pricked up this week when I heard of an attraction available at the Italian town of Caldari di Ortana in Abruzzo. I had previously associated it with a stop off on the Cammino di San Tomasso, the route along which pilgrims tramp from Ortana where the bones of St Thomas are supposed to lie to St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Not being a left footer and doubting the provenance of the bones, I have always left it at that.

Now, though, there is a reason for going. The Dora Sarchese winery has installed a 24 hour, free, red wine fountain in the town. Apparently, it works like one of those push button water drinking fountain jobbies. The winery was coy as to the type of wine on offer so I suppose you have to take a chance but even a coarse Italian red gratis would be acceptable.

The courtiers of Henry VIII and the French king Francis I had a wine fountain to enjoy when the two monarchs met in 1520 and there is a famous picture of some of them lolling around at its base in a drunken stupor. Dora Sarchese say that their largesse is not to promote public drunkenness but to offer succour to weary pilgrims. Wait until the stag party operators hear about it!

Filed under: Humour, News Tagged: Caldari di Ortana, Cammino di San Tomasso, Italian town instals red wine fountain, St Thomas, The Dora Sarchese winery

October 21, 2016

What Is The Origin Of (102)?…

Make no bones about

This phrase is used to make a vehement assertion about something, as in “make no bones about it, this is going to be interesting”. Alternatively, it can be used to indicate that someone does something without objection, as in “she made no bones about taking the dog for a walk”. The origin of this phrase is harder to unravel.

What we do know is that it has a long pedigree as a variant first appeared in print in 1548 in Nicholas Udall’s The first tome or volume of the Paraphrase of Erasmus vpon the Newe Testamente, where he described Abraham who “made no manier – a comparative of many – bones ne stykyng (hesitation), but went in hande to offer up his only son Isaac”. By the late 16th century making no bones made an appearnce – Marbeck’s Book of Notes of 1581 noted, “whatsoever matter is intreated of, they never make bones in it” and in 1597 in the chapter on incestuous persons in Thomas Beard’s The Theatre of God’s Judgements, “divers of the Roman Emperours were so villainous and wretched as to make no bones of this sin with their owne sisters, as Caligula, Antonius and Commodus”.

An earlier variant still was the phrase, to find no bones is something. This appeared in a letter written by Friar Brackley to John Paston in 1459 regarding a legal dispute, “Mayster R Popy, a cunnying and crafty man…and fond that tyme no bonys in the matere”. Clearly, the bones are being used in this context to denote obstacles or objections. The absence of bones (obstacles) enabled the crafty so and so to agree to what was being proposed.

So what are we to make of these bones? We have seen before that mediaeval and Tudor foodstuffs often left a lot to be desired in terms of quality. You were not always eating what you thought you were and sometimes foreign and cheaper bodies would be added to increase the supplier’s profit. An unwelcome surprise, although not as unwelcome as some I’m sure that could be experienced, was to find a bone in a pudding, pie or soup – at least you could be certain it came from a previously living creature. One theory is that the expression comes from the gastronomic delight of not discovering a foreign object in your tucker.

Adherents of this theory draw upon John Skelton’s The Tunnying of Elynour Rummyng of 1516 in which the eponymous protagonist brewed a strong ale and gave a cup to a drunken woman, Ales. “Ales found therein no thornes/ but supped it up at ones/ she found therein no bones”.

Making bones appeared in Thackeray’s Pendennis of 1850, “do you think that the government or opposition would make any bones about accepting the seat if he offered it to them?”, where bones are clearly objections. And, I think, this is our clue. Bone is not a foreign object found in your food, it is a figurative description for strife or disagreement. There are a number of proverbs where bone is used in this sense – tonge breketh bone (speech causes strife), it is said that although itself has none, a tongue breaks the hard bone to pieces and fair words never break bones , to name just three.

Perhaps some strength is added to the theory by considering the French equivalent, ne pas macher ses mots (don’t chew your words). I won’t make any bones of whichever version you accept.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: bones used figuratively to mean strife, ne pas macher ses mots, origin of make no bones about, The Tunnying of Elynour Rummyng, to find no bones in

October 20, 2016

I Predict A Riot – Part Fifteen

The eel pulling riot, 1886

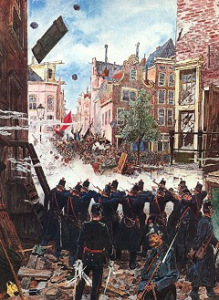

Throughout history people have found some strange ways to keep themselves amused. I’m not sure I quite see the attractions of palingtrekken or eel pulling but it was amazingly popular amongst the poorer sorts in 19th century Amsterdam.

It was a pretty simple sport. A rope would be stretched across a canal and a live eel would be suspended from the middle of it, hanging down. Contestants would then stand in open boats navigating the canal and would try to snatch the poor creature free. Great acclaim was reserved for anyone determined enough to release the eel. But, of course, an eel is metaphorically slippery and in the predicament it found itself would be scared out of its wits. This meant it was difficult to grasp and many a contestant would find themselves in the water of the canal, to the amusement of the crowds of bystanders on the bank. What sport!

Even by the standards that endured in the late 19th century palingtrekken was recognised, by the authorities at least, as a gratuitously cruel sport and attempts were made to clamp down on the fun. Organisers announced in July 1886 that they were going to stage a contest at the Lindengracht. This was duly banned by the authorities.

Notwithstanding this minor inconvenience, the organisers pressed on and on Sunday 25th July a large crowd gathered on the banks of the Linden canal to watch the proceedings. The police moved in and their attempts to put a halt to contest were resisted by the locals. A full-blown riot ensued and order was only eventually restored that evening.

But that wasn’t the end of the affair. The following day the residents of the poor and working class quarter of Jordaan joined and matters took a more serious and disturbing turn. Paving stones were ripped up to serve as missiles and barricades were erected on the streets. The police moved in and were pelted with heavy objects thrown down from the roofs of the nearby buildings. A crowd armed with sticks and rods lay siege to the local cop shop. So serious was the violence that the army had to be brought in and permission was granted to fire live ammunition – to disastrous effect.

The barricades were torn down, one by one, as the army swept through the district, firing randomly until order was finally restored by nightfall. 26 people had lost their lives and over one hundred people had been injured.

In the immediate post-riot enquiry concerns were voiced that this riot had more sinister overtones and was part of a socialist plot to overturn Dutch society. Many of the rioters who had been arrested were interrogated but the public prosecutor concluded that the riot had been spontaneous, rather than planned. It was, however, a popular expression of the discontent of the poorer classes over their lot and heavy-handed authoritarian attempts to deny them what pleasure they could find.

As for the eel that was hanging from the canal bridge whilst all hell broke out, it was taken down and reputedly sold, in 1913, for the princely sum of 1.75 guilders, after which it disappeared, never to be seen again. I would assume it was too old to be eaten.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: death toll in eel pulling riot, eel pulling, Lindengracht, palingtrekken, the eel pulling riot of Amsterdam 1886

October 19, 2016

Gin o’Clock – Part Thirteen

In my notes on my exploration of the ginaissance I have briefly alluded to Old Tom gin, a style of gin which has been rescued from obscurity. It has been described as the missing link, sitting halfway between the drier London dry gin and the sweeter Dutch Genever. This is because a sweetener, often sugar, is used in its distillation, something that is verboten in the production of London dry gin.

In the 19th century it was all the rage. Henry Johnson described it in his Bartender’s Manual of 1882 as one of the essential “liquors required in the bar room”. He included Old Tom in everything from a refreshing Tom Collins to a sparkling gin fizz. But over the last century or so it was a style of gin that fell out of favour. Only the revival in interest in gin and old gin recipes has restored it to its former glory as the go-to gin base for a cocktail.

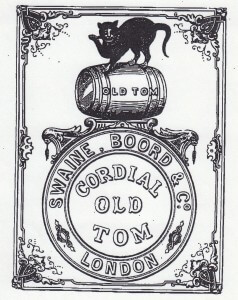

How did it get its name? Well, the story goes that in 1736 Captain Dudley Bradstreet established an ingenious method of dispensing gin to counteract the government’s attempt to prohibit the sale of the hooch. He put a sign depicting a moggy in the window of his gaff and let it be known that gin could be purchased by the cat. Underneath the sign was a slot into which a customer would insert their money and the gin would be dispensed through a pipe either into a cup or directly into the toper’s mouth. This arrangement caught on and many establishments offered a service where a customer would call out “puss” and, if they heard an answering “meow”, they knew their luck was in and they would get their hands on some gin. Old Tom became an affectionate nickname for gin. In 1849 Joseph Boord registered the image of a cat for his Old tom gin, the oldest registered trademark for gin.

The increase in the sugar trade in the 19th century meant that it was within the price range of the ordinary person who as a consequence developed a sweet tooth. It was natural for gin to follow this trend and the introduction of the continuous still enabled a cleaner neutral spirit to be used as the base for Old Tom gin. Often Old Tom was advertised as sweetened gin and by the late 19th century was sold with an ABV of around 40 to 44%.

The modern revival in the interest in Old Tom was sparked by Hayman Distillers and it is appropriate, therefore, that Hayman’s Old Tom Gin should be our featured gin of the month. It comes in a distinctive square, squat bottle with green labelling and a foil cap a la a bottle of wine with a natural cork stopper. It is clear and to the nose has a distinctive juniper and zesty orange smell. To the taste it is slightly sweet with juniper dominating, although spice and citrus can be detected. The aftertaste is long-lasting and predominantly spicy.

The gin was launched in 2007 and follows a recipe perfected by a family ancestor, James Borough, in the 1860s or 70s. As noted before, all Hayman’s different gins use the same ten botanicals – juniper, coriander, lemon peel, orange peel, angelica root, cinnamon, cassia bark, orris root, liquorice and nutmeg – although the proportions differ and, of course, sugar is added for the distinctive Old Tom taste.

A very acceptable alternative to the London Dry gin I have been quaffing.

Filed under: Gin Tagged: Captain Dudley Bradstreet, cats and gin, ginaissance, Hayman's Old Tom Gin, history of Old Tom Gin, Joseph Boord, Old Tom gin

October 18, 2016

Quacks Pretend To Cure Other Men’s Disorders But Rarely Find A Cure For Their Own – Part Forty Four

Angelick snuff

For some a more sophisticated way of ingesting tobacco is via the snout in the form of snuff. No need to ignite a cigarette or cigar and pollute the room and inconvenience bystanders with their noxious fumes. Simply tip some of the powder on to the back of your hand and sniff vigorously. The effects are almost instantaneous and the resulting sneezing fit will be loud and soil your handkerchief with the contents of your nose.

I had never considered taking snuff to have any medicinal benefits but, perhaps, that is because I had overlooked Angelick snuff, so named because it was flavoured with angelica rather than because it was manna from heaven. It was available in the first half of the 18th century and, according to an advertisement which appeared in the Daily Post of January 17th 1739, only available from Jacob’s Coffee House, against the Angel and Crown Tavern in Broad Street, behind the Royal Exchange in London, price one shilling a paper with directions.

As we have grown to expect, the claims for its properties were fulsome. The advertisement described it as “the most noble composition in the world”. So what was it good for? Well, you name it. “instantly removing all manner of disorder of the head and brain, easing the most excruciating pain in a moment; taking away all swimming or giddiness, proceeding from Vapours, or any other cause”. But that was not all, “also drowsiness, sleepiness and all other lethargic effects, perfectly curing deafness to admiration, and all humours and soreness in the eyes, wonderfully strengthening them when weak”.

The list of maladies that succumbed to the power of the snuff included catarrhs, defluxions of rheum and toothache instantaneously. It was also claimed to be beneficial in apoplectic fits and falling sickness as well as comforting the nerves and raising the spirits. And then to testimonials, “its admirable efficacy… has been experienced above a thousand times and very justly causes it to be esteemed the most beneficial snuff in the world, being good for all sorts of persons. And as most of the above disorders are sudden, and the remedy by this most noble Angelick snuff as speedy, no family ought to be without it, nor ever will, when they have once used it”.

A reference in the Spectator claimed it was only available at Mr Payn’s Toy Shop but as this was also said to be by the Angel and Crown Tavern, I suspect this was the same as the Coffee House. Whilst probably not injurious, at least if you shut your eyes to the addictive and carcinogenic properties of concentrated tobacco, it is hard to imagine that it had the slightest effect on many of the maladies cited in the glowing advertisement. It may have caused a momentary distraction, watering of the eyes, volcanic sneezing fits and the like, which took the user’s attention away from anything else that was afflicting him. At best, it was a temporary fix but, of course, that meant you had to repeat the dose – more money for the supplier and enhancing the chances of addiction.

When you indulge in something that you know deep down is bad for you, it is a comfort to delude yourself that it may just be doing some good too.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: angelica, Angelick snuff, Jacob's Coffee House, Mr Payn's Toy Shop