Martin Fone's Blog, page 312

November 16, 2016

Gin o’Clock – Part Fifteen

A question for regular topers – when is it acceptable to have the first snifter of the day? There is a delicate balance to be struck, to be sure – too early and you run the risk of appearing to be in the thrall of the demon drink and too late and you have let valuable drinking hours slip you by, requiring you to create the impression that you have a real thirst on to make up for lost time.

For me the bewitching hour is midday. That twelve hour stretch between midnight and noon gives the body enough time to clear out the excess of the previous day, leaving half a day to enjoy a drink or three at a leisurely pace. After all, the wide array of drinks that the ginaissance has spawned requires that they be appreciated in all their glory. Some, though, take a different approach. Edward Kain, a Victorian engineer, inventor and gentleman was in the habit of retiring at six o’clock in the evening to his favourite armchair with a gin and tonic in hand, his first of the day, to allow his mind to mull over some thorny engineering problem. His restraint was commendable.

His great-grandson, Michael Kain, director of Bramley & Gage, based in Thornbury just outside of Bristol, has produced this month’s featured gin, 6 o’clock Gin, to celebrate this diurnal habit. It comes in a stout, dumpy, domed, dark blue bottle with a glass stopper. The front of the bottle has a strikingly simple design with mechanical cogs inside the number six and the legend “strikingly simple”. On the back of the bottle there is some verbiage explaining that the hooch is distilled in their custom-built copper pot still, funded through peer-to-peer lending incidentally, with its unique double sphere head. My bottle is marked lot number 618108 , bottle number 0654, coming in at a respectable 43% ABV.

However, they are remarkably coy as to what is in the gin. As well as the obligatory juniper, there are six botanicals but to date I have only been able to identify for certain coriander, orris, angelica, orange peel and elderflower. From my tasting there seems to be a hint of liquorice. To the nose this crystal clear spirit is full of juniper and orange. To the taste it is smooth but for me the juniper is overpowering at the expense of the other botanicals and the aftertaste is of tannin. It is a very refreshing drink and is perfect for supping on a hot summer day, alas long since gone now. I found it less satisfying when mixed with an aggressive tonic like Fever-Tree and was better with a milder, sweeter tonic.

As a botanical liquorice contains a natural sweetener called glycyrrhizinic acid which is over twenty times sweeter than ordinary sugar. Distillers used it for these properties and it is thought that liquorice was a popular substitute for sugar in the making of Old Tom gin. Liquorice also contains anethole which gives it its characteristic anise flavouring. Anethole is less soluble in water than it is in ethanol and so when water is added to the spirit to reduce the strength, the spirit can take a cloudy appearance. Distillers who want to use liquorice but maintain a pure spirit have to chill filter it.

Until the next time, whatever hour it may be, cheers!

Filed under: Gin Tagged: 6 o'clock gin, anethole, Bramley & Gage, Edward Kain, Fever-Tree premium Indian Tonic water, ginaissance, glycyrrhizinic acid, liquorice

November 15, 2016

The Streets Of London – Part Fifty

Inner Temple Lane, EC4Y

I spent part of my illustrious working career in offices adjacent to the Temple, the home of London’s barrister community. One of the pleasures of working in that area was wandering through the warren of lanes that make up that neck of the woods, observing legal minds strolling around grappling with some obtuse point of law or, more likely, designing strategies for extracting more fees from their clients.

Inner Temple Lane was one of my favourites, principally because of the solid stone gateway at the north end which leads on to Fleet Street and the magnificent black and white timbered building that fronts on to Fleet Street. It is the City’s sole surviving timber-framed Jacobean townhouse. That it has survived is a miracle.

The stone gateway was originally part of the estate of the Knights Templar, passing to the Order of St John of Jerusalem – the Knights Hospitallers. The latter are responsible for the area’s legal connections, having leased to lawyers considerable pockets of land south of Fleet Street south of Fleet Street so they could ply their trade. The Jacobean townhouse was built around 1610 and contains a beautiful chamber known as Prince Henry’s Room, named after James the First’s son, the plaster work, extant, containing representations of flowers, three feathers and the initials P H. Henry can’t have enjoyed the room for long as he died at the age of eighteen but it may well have served as a council chamber for the Duchy of Cornwall.

The building survived the Great Fire and part of it was used as a pub, initially the Hand Inn and then the Prince’s Arms. From 1795 the premises, now known as the Fountain, were leased by Mrs Salmon and housed her enormously popular collection of waxworks. Amongst the delights on offer was a clockwork model of Mother Shipton which kicked visitors as they departed, thanks to hidden treadles under the floorboards. Other highlights included were what were termed as anatomical waxes alongside tableaux, one of which was “Shepherds and Shepherdesses making violent love”. A young Charles Dickens was a regular visitor and in David Copperfield he has his eponymous hero going “to see some perspiring waxworks in Fleet Street”. After Mrs Salmon’s death the collection was sold and relocated at Water Lane.

A photograph of the gateway dating to around the 1870s shows that the premises were occupied by Carter’s Ladies and Gentlemen Hair Cutting Saloons, offering hair cutting and shampooing services as well as steam-powered hair brushing. The front window proclaimed that a haircut would cost you six pennies. It also offered wigs for sale and the items on sale look to be of a judicial nature rather than syrups you might buy if the steam-powered hair brush had chewed up your barnet.

Large hoardings proclaimed the building to be “formerly the Palace of Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey” but advertising standards being somewhat laxer in those days there is no evidence that it was. What was apparent was that the building was in a dilapidated state with its frontage boarded up and the Jacobean timbers hidden under numerous coats of paint. It was only rescued and restored to its former glory about a century ago. Prince Henry’s Room has been open to the general public since 1975, usually afternoons but check if you are thinking of going, and hosts an exhibition of Samuel Pepys and the London he lived in.

We should be grateful that this wonderful landmark has survived the vicissitudes of fire, war, time and taste.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: Charles Dickens, David Copperfield, Inner Temple Lane gateway, Mother Shipton, Mrs Salmon's waxworks of Fleet Street, Prince henry's Room, Samuel Pepys

November 14, 2016

I Don’t Want To Belong To Any Club That Will Accept People Like Me As A Member – Part Twenty Eight

The Scriblerus Club

This club, formed in 1714, was more of a literary collective and was formed of some of the sharpest literary talents of the age including Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Gay, John Arbuthnot and Thomas Parnell. It took its rather curious name from a cod scholar, Martinus Scriblerus, whom the group created to represent the kind of pedantic scholar who was to be the butt of their satire. Swift was given the nickname Martin by the group – a rather lame play on the ornithological derivation of his surname – and the pedant’s first name was given in his honour. Instead of concentrating on humanistic matters Scriblerus would spend his time in the Gradgrindian tasks of checking facts and trivial details.

The club’s aim was to develop a canon of literature that attacked the then trend for excessively literal approaches to academic subjects, ranging from medicine to philosophy. The members’ goal was to produce satirical commentary on the abuse of human learning, on the assumption that ridiculing these prevailing ideas and approaches was the best way of minimising their influence. They met occasionally, usually at Arbuthnot’s house.

The problem was that with such an array of mercurial talents in membership disputes were bound to occur and this sounded the death knell for the club. As Sir Walter Scott commented in his Life of Swift, “the violence of political faction, like a storm that spares the laurel no more than the cedar, dispersed this little band of literary brethren, and prevented the accomplishment of a task for which talents so various, so extended, so brilliant, can never again be united.”

Swift tried to play the role of peacemaker. He wrote a fable of Fagot where the ministers of the land are called upon to contribute their various badges of office to make the bundle strong and secure but his diplomatic entreaties fell on stoney ground. In a huff Swift retreated to Berkshire where he stayed in seclusion for some weeks.

Although short-lived as a club, the legacy of Martinus Scriblerus lived on. The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus, published in 1741 in a volume of Pope’s works, although much of it was written by Arbuthnot, tells of his upbringing and education. Such was the energy and enthusiasm that they invested in this project that Pope confided to Swift in a letter that “the top of my own ambition is to contribute to that great work and I shall translate Homer by and by”. You can imagine the fun they had in creating their character.

Pope’s Dunciad Variorum, published in 1729, incorporates Scriblerus’ fastidious notes, penned by Pope. And probably the most famous product of the club was Swift’s own Travels of Lemuel Gulliver, the third book of which concerns the visit to Laputa and which betrays the stamp of Scriblerus. Gay’s Beggar’s Opera grew out of a suggestion made by Swift at the club and Henry Fielding’s The Welsh Opera (1731) was presented as a tribute to the Scriblerians and satirised the government. His pen name was Scriblerus Secundus, naturally.

A short-lived club that had a long-lasting influence on English literature.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: Alexander Pope, Gradgrindian, John Arbuthnot, Jonathan Swift, Martinus Scriblerus, Scriblerus secundus, the Dunciad variorum, the fable of Fagot, The Scriblerus Club

November 13, 2016

Toilet Roll Of The Week

For the household that has almost everything, I read this week, Tesco have launched a luxury soft tissue bog roll which smells of mulled wine. On sale in all of its UK retail outlets it contains citrol, eugenol, cinnamol, citronella and limonene. According to a spokesperson, “it has a mulled spice fragrance core and a decorated paper for extra indulgence everyday”.

Apart from the obvious why, the other $64,000 question is whether its fragrance is strong enough to mask the odour of digested Brussels sprouts. Only time will tell, I guess.

It has never crossed my mind to sniff a toilet roll but perhaps it will catch on. After all, stranger things have happened this week.

Filed under: Humour, News Tagged: Brussels sprouts, mulled wine scented toilet roll, Tesco, Tesco launch mulled wine toilet rolls

November 12, 2016

Advert Of The Week

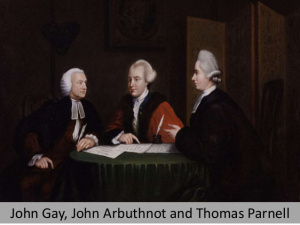

Christmas is coming and we are being inundated with adverts. so it takes something special to grab our attention, like this ad which sells the delights of Australia’s Northern Territories to potential tourists.

It is colourful, direct, uses , an iconic image and deploys the modern taste for acronyms effectively and for those of a certain disposition has the potential to cause offence.

Bonzer, I think they say.

Filed under: Humour, News Tagged: humorous advert for Northern Territories, new advert for Northern Territories, NT Official

November 11, 2016

What Is The Origin Of (105)?…

Flea in your ear

We deploy this phrase when we dismiss someone with words of sarcastic advice or reproof ringing in their ears. It denotes giving someone a sharp oral rebuke. The phrase first appeared in the written English language as far back as 1426 in John Lydgate’s The Pilgrimage of the Life of the Manhood, manhood denoting the human condition. Lydgate’s work in turn was a translation of a devotional work by the French Cistercian monk, Guillaume de Deguileville.

Flea is a term given to any small, flattened, wingless, bloodsucking insect of the order Siphonaptera. They are parasites and are best known for their prodigious ability to leap. Even today they can be found on even the best groomed of our domestic pets and in medieval times when hygiene and living standards were considerably lower you can imagine that they were frequently encountered in the home. If you were unfortunate enough to have a flea jump into your ear, the experience would doubtless have been unpleasant with the flea wriggling around, trying to jump to freedom and probably giving you a nip or two along the way.

Interestingly, though, Deguilville didn’t use the term to suggest a sense of irritation or discomfort, rather using it to denote the sort of spiritual emotion that is evoked by contemplating great wonders. Indeed, in mediaeval French the phrase “avoir la puce a l’oreille” was used to describe the amorous or sexual desire you felt for someone, a meaning it retained until at least the 17th century when Jean de la Fontaine wrote, “a longing girl/ with thoughts of sweetheart in her head/ in bed all night will sleepless twirl./ A flea is in her ear, ‘tis said”. The agitation caused a lovelorn maiden by thoughts of her beau were considered from a figurative standpoint akin to the frantic and jerky movements of an animal trying to rid itself of an unwelcome visitor from its ears.

And in more modern times the French use their version of the expression to denote having doubts or someone putting suspicions into your head. This sense is broadly repeated in similar expressions found in German, Italian and Greek, the flea perhaps taking the role of an external influence whispering messages of distrust into your ear. The Dutch use a flea in the ear to denote someone who is fidgety or restless, preferring to concentrate on the visible signs of someone or something being attacked by fleas.

Not for the first time is the English-speaking community at odds with our European friends. We have tended to concentrate on the physical discomforts that having a flea in your ear can cause and have used it figuratively through the centuries to equate that physical pain with the mental anguish caused on receipt of a stern telling off. The mathematician and alchemist, John Dee, wrote in a letter in 1586, although not published until 1659 in True Faithful Relation..and Spirits, “at length had such his answer, that he is gone to Rome with a flea in his eare that disquieteth him”. John Arbuthnot wrote in his History of John Bull, published in 1712, “we being stronger than they, sent them away with a Flea in their Ear”. Ryder Haggard in Jess, published in 1887, wrote “I sent him off with a flea in his ear, I can tell you”. No sign of doubt, suspicions or amorous feeling there!

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: avoir la puce a l'oreille, Guillaume de Deguileville, John Arbuthnot, origin of flea in your ear, Siphonaptera

November 10, 2016

Double Your Money – Part Eleven

The South Sea Bubble of 1720

The lure of easy money has always been one hard to resist – even governments are on the look-out for an easy way out of their financial difficulties. The War of Spanish Succession (1701 – 1714) had left the British government on its uppers and they promised the South Sea Company, formed in 1711, a monopoly of all trade to the Spanish colonies in South America in return for taking over and consolidating the national debt. The Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 which confirmed Spanish sovereignty over its South American colonies scuppered the company’s chances of exploiting its franchise.

Nonetheless, the company pursued a strategy to become the guarantor of choice for the British government, persuading it in 1719 to convert additional portion of national debt into South Sea Company shares, offering interest of 5% paid by the government. The share price of the company stood at £128 in January 1720 but as more national debt was underwritten by it the price rose to £175 in February and to £330 by the end of the following month when it saw off competition from the Bank of England to underwrite even more debt.

As we have seen elsewhere a nascent stock exchange was forming in London and in 1720 those who were unable to get their hands on South Sea company stock found that there were a remarkable number of start-ups vying for their fortunes. Some companies were lunatic – one was set up to manufacture a gun to fire square cannon balls – or fraudulent – one’s mission statement was “for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage but no-one to know what it is” and attracted £2,000 of investors’ money – and others wildly optimistic – one company was established to buy the Irish bogs. Most people with money or savings plunged in with gay abandon.

In June 1720 Parliament passed the Bubble Act requiring all joint stock companies to receive a royal charter, an attempt by the South Sea Company to control competition in a frenzied market. When the Company got its charter its share price rocketed to £1,050. To meet the demand for shares the company issued more, even lending would-be investors the money to pay the initial deposit – a fatal flaw that would have tragic consequences.

When in August the first instalments of the money subscriptions on South Sea stock were due and many investors had subscribed without the financial resources to meet their obligations. Their only recourse was to sell. This in turn triggered a fall in the share price – by September it was down to £175 – ruining many who were unable to recoup their investments. Many, including members of the clergy and gentry lost their life savings and those who had staked everything became destitute overnight. Suicide rates increased dramatically.

Retribution for the disaster soon followed. The Directors of the Company were arrested and their estates forfeited and as a result of a Parliamentary enquiry – 462 MPs and 112 Peers were involved in the company – John Aslabie, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and several MPs were expelled from parliament in 1721.

To rectify the situation Robert Walpole was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer and he split the National Debt that had been placed with the company between the bank of England, the Treasury and a sinking fund, a portion of the nation’s income that was put aside each year. Eventually financial stability was restored and a salutary lesson about the vagaries of investing in shares was learnt by all.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: John Aslabie, Robert Walpole, the cause of the south sea bubble, the consequences of the south sea bubble, the South Sea Bubble, the South Sea Company, Treaty of Utrecht, value of South Sea Company shares

November 9, 2016

Book Corner – November 2016 (1)

After Me Comes The Flood – Sarah Perry

This is not a book I would have ordinarily picked up but I was so besotted by The Essex Serpent, my stand-out book of 2016 by a country mile, that I was tempted to explore her debut novel, After Me Comes The Flood. I was not disappointed and found the book strangely compelling.

Without giving too much away, a bookseller named John Cole walks out of his shop after 35 days of drought and drives towards the Norfolk coast to visit his brother. On the way his car breaks down – unreliable motors seem a frequent literary motif in books I have read in the last couple of years – and instead of ringing the AA as most of us would have done, he sets out on foot and comes across a house. He is welcomed in by the occupants – a strange crew consisting of a former preacher, Elijah (natch), a beautiful pianist, Eve, the ingénue Claire and her fragile brother Alex, a sinister man called Walker and the matriarch of the house, Hester. What is more, they seem to be expecting him, indeed waiting impatiently for him to arrive.

The book relates events over a week, a chapter for each day. The style is a mix of first person as John tells us of his thoughts and experiences and third person narrative. The first part of the book deals with John’s attempts to find out what this small community is all about, why they are there and his fears as to what they might do if they discover that he is an impostor, something Walker suspects from the outset. John seems unable to leave the house, even though he has opportunity to do so. Perry portrays a place where the atmosphere is claustrophobic and disconcerting in an excellent first half.

For me some of the tension went out of the book when we learn why everyone knew John’s name and who they are and how they fit together. The characters are rather one-dimensional, almost caricatures and little attempt is made to get us to warm to any of them. What the book may lack in that direction, it more than makes up for it in the portrayal of a sense of doom hanging over the community. Perry’s descriptions are evocative and laden with atmosphere – it has a touch of the Gothic. The principal fear, at least of Alex with whom John forms a friendship, is that a storm cometh which will cause the reservoir nearby to breach and inundate the community.

I will not spoil the ending but it merits careful reading. Perry’s prose has a dreamlike quality which complements her development of this strange environment. There are symbols galore – who is Eadwacer? What are the implications of the two meat hooks hanging in the kitchen, the graffiti carved in the furniture and the broken sundial? Save for a telephone call and a reference to a mobile phone there is a timeless quality to the story. It is probably set in the modern-day but it doesn’t really matter. Events occur in a vacuum. As Perry says, you don’t have to know the meaning of everything; you just have to know it has meaning.

If I had to quibble I would say the plot is a bit thin and the second half of the book is not a patch on the first. As a debut novel, it is extraordinary and you can see the seeds that gave birth to the Essex Serpent. If you were only to read one of her books, read that. If you choose to read both, come to this second.

Filed under: Books, Culture Tagged: After Me Comes The Flood, debut novel of Sarah Perry, Eadwacer, Sarah Perry, the Essex Serpent

November 8, 2016

Quacks Pretend To Cure Other Men’s Disorders But Rarely Find A Cure For Their Own – Part Forty Five

John Hill (1714 – 1775) and his Pectoral Balsam of Honey

Our latest quack, John Hill, was a noted botanist in his time and was a prolific writer, perhaps best known for his 26 volume The Vegetable System – its full title running to 58 words required a volume in itself. He was also a man of letters but was very disputatious and vexatious, traits which earned him many an enemy. Samuel Johnson described him as “an ingenious man but [who] had no veracity” and the actor David Garrick wrote of him, “for physics and farces, his equal scarce there is;/ his farces are physic, his physic a farce is.” The Swedes, the race that is not the vegetable, seemed to like him awarding a knighthood.

For a quack Hill was unusual in that he had a medical degree and he put this and his botanical knowledge to good use by creating a number of herbal-based remedies including the pectoral balm of honey. He used the monies earned from his medicines to fund the publication of his books and earned a considerable fortune.

Honey has a long medicinal history, the ancient Egyptians using it for embalming bodies and dressing wounds as well as an offering to the gods. Holisitic practitioners consider it to be one of nature’s best all-round remedies but scientific claims for its efficacy are unproven other than for the care of wounds and the suppression of coughs. When I have a tickle in my throat, I like to suck a honey flavoured lozenge.

The trouble with honey, though, is that concentrated honey was difficult to obtain in a quantity and at a cost that made a honey-based balsam commercially viable. The actual base for Hill’s balsam, according to the Modern Domestic Medicine of 1827 was an ounce of balsam of tolu – a South American resin which is still today used in cough syrups – a drachm of gum storax, fifteen grains of purified opium, four ounces of best honey and a pint of rectified spirit of wine. The brew was left to mix for five or six days and then strained. Voila.

As we have grown accustomed to expect, the advertising that accompanied the balsam was effusive in its praises. “..the unequalled efficacy and safety of this elegant Medicine in the immediate relief and gradual cure of coughs, colds, sore throats, hoarseness, difficulty of breathing, catarrhs, asthma and consumptions.” A large tea-spoonful mixed in a wine glass of water made a dose “converting the water into a most pleasant balsamic liquor, to be taken morning and evening.” Bottles sold at 3s 6d and bore the signature H.Hill – adverts warned the reader to be wary of imitations – and were available from 150, Oxford Street and a couple of outlets in the City and one in Borough.

Whether it worked or not is unclear but the mix of wine, opium, honey and tolu would not have been unpleasant to the taste, at least. But the principal ingredient of the balsam was tolu not honey as the Medical Observer of 1808 pointed out. “The Balsam of Tolu, from its fragrant aromatic smell, is a ready and cheap substitute [for the faff of producing concentrated honey]. This deception was first begun by Sir John Hill who..did not lose sight of a balsam of honey which is nothing less than a balsam of tolu sold under this name. We regret that a man of Sir John Hill’s abilities should have been put to such shifts.”

Hill’s ability to stir up a hornet’s nest survived his death but he did very nicely out of the sales, thank you very much.

Filed under: Culture, History Tagged: balsam of tolu, David Garrick's opinion of Sir John Hill, Doctor Samuel Johnson, medicinal properties of honey, Pectoral Balsam of Honey, recipe for pectoral balsam of honey, Sir John Hill, the Medical Observer

November 7, 2016

There Ain’t ‘Alf Some Clever Bastards – Part Sixty One

Wilhelm Rontgen (1845 – 1923)

Without question, one breakthrough that has revolutionised the medical profession is the discovery of the x-ray machine. The process of x-raying a patient in a hospital or in the dentist’s chair to get a picture of what is going on inside is so routine that we barely give it a second thought. But someone somewhere must have identified these radioactive rays which illuminate our insides and this is where the latest inductee of our illustrious Hall of Fame, the German physicist, Wilhelm Rontgen, comes in.

During the course of 1895 he began investigating what happened when an electrical discharge was passed through various types of vacuum tubes. In early November he was concentrating on testing a tube created by Philipp von Lenard which had been modified by adding a thin aluminium window to allow the cathode rays to escape and a cardboard covering to stop the aluminium from being damaged. Despite the cardboard cover stopping light escaping, Wilhelm noted that when a small cardboard screen coated with barium platinocyanide was placed close to the aluminium window a fluorescent glow could be detected.

On 8th November Rontgen then turned his attention to the Hittorf-Crookes tube which had a thicker glass wall, covering it with cardboard and attaching it to a coil to generate an electrostatic charge. He darkened the room and as he passed the coil charge through the tube, he noticed a shimmering effect which came from the barium platinocyanide screen he had placed nearby. It dawned on him that he may have isolated a new form of ray which he dubbed x, using the algebraic notation used to denote an unknown quantity.

Locking himself away in his laboratory for a couple of weeks to examine the properties of these rays, Wilhelm summoned his wife, Anna Bertha, and took the world’s first x-ray. When she saw the bones of her hand, his old Dutch exclaimed, “I have seen my death”. It’s hard being an inventor’s wife.

When experimenting to see which materials had the ability to stop the rays, Rontgen positioned a small piece of lead while the discharge was occurring. On the screen he saw his own skeleton, flickering and ghostly – the first radiographic image. He published the first of three papers he wrote on his discovery – Uber eine neue Art von Strahlen (On a New Kind of Rays) – on 28th December 1895 and was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Wurzburg. In 1901 Wilhelm was awarded the very first Nobel Prize for Physics.

But as we come to expect from our inductees, financial success didn’t follow his landmark discovery. Firstly, and nobly, he refused to patent his discovery, wanting mankind to benefit from the practical applications of his discovery. The prize money from the Nobel award, he donated to his university at Wurzburg.

But philanthropy doesn’t make you immune from harsh economic reality. Despite inheriting a fortune, 2 million Reichsmarks, on his father’s death, the rampant inflation of the Weimar republic ate into it and shortly after the end of the First World War he was declared bankrupt. He saw the rest of his life out quietly at his country home in Weilheim, near Munich, and on his death in accordance with his wishes, his personal and scientific correspondence was destroyed.

Wilhelm, for identifying x-rays and refusing to patent your discovery, you are a worthy inductee into our Hall of Fame.

If you enjoyed this, why not try Fifty Clever Bastards by Martin Fone which is now available on Amazon in Kindle format and paperback. For details follow the link https://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Daps&field-keywords=fifty+clever+bastards

Filed under: Culture, History, Science Tagged: Anna Bertha Rontgen, barium platinocyanide plate, Fifty Clever Bastards, first x-ray, Hittorf-Crookes tube,