Martin Fone's Blog, page 174

December 11, 2020

Cantering Through Cant (12)

Groups and associations, particularly the rank and file of the military, are keen to impose their own forms of discipline on their colleagues. Francis Grose’s A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785) is full of examples. Here are just three.

Cob or cobbing Grose describes as “a punishment used by the seamen for petty offences, or irregularities, amongst themselves; it consists of bastinadoing the offenders on the posteriors with a cobbling stick, or pipe staff; the number usually inflicted is a dozen”. The first blow is followed by the cry of Watch, at which point, for fear of punishment, all present must remove their hats. The last stroke, which is always the hardest, Grose informs us, is known as the purse.

Soldiers also practiced this rather barbaric form of punishment but did not include the watch or purse in the number of strokes to be inflicted. These were additional or, as our compiler notes, given “free, gratis and for nothing”. The practice was also used by schoolboys to punish anyone who had the audacity to enter their halls of learning while still wearing a hat.

Cold burning was “a punishment inflicted by private soldiers on their colleagues for trifling offences, or breaches of their mess laws”. The unfortunate victim would be ties to the wall with his arm raised and the master of ceremonies would proceed to pour a jug of cold water down the sleeve, patting it all the while, to ensure that it travelled down his body before exiting from the knees of his breeches.

Indolence in the form of a marked reluctance to leave the bed is not a modern trait. Grose records that cold pig consisted of stripping the bedclothes from the bed and pouring a jug of cold water over the idler.

December 10, 2020

William Kerr’s Border Gin

I picked up a bottle of William Kerr’s Border Gin on my latest trip to Constantine Stores. William did not mind as he is dead and, apart from lending his name, unbeknownst to him, to the gin, has nothing to do with the hooch. Who was Kerr, you might ask? Born in the Scottish Border’s town of Hawick in 1779, William Kerr moved south to seek his fame and fortune, joining the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew as a gardener. In 1804 he went to Asia where he developed a reputation as a plant collector, 238 of the plants he sent back to Kew representing new species. The Kerria, a vigorous, deciduous spring flowering shrub, also known as Jew’s mantle, was named after him. In 1812 Kerr was appointed as superintendent of the newly created botanical garden in Colombo, but, sadly, died within a couple years of his arrival in Sri Lanka.

It seems a natural fit, then, for a product distilled in Hawick using botanicals to be named after the town’s most famous horticultural son. The Border’s Distillery, responsible for the gin, are the first to operate in the Borders since 1837 and also produce malt whisky and vodka. For all their products they only use barley sourced from farms within a twenty-mile radius of the distillery. The water used is drawn from an underground lake beside the distillery, fed from the local hills.

As for the botanicals that go into the mix, we find juniper, lemon, bitter orange, sweet orange, coriander, angelica, orris, almond, liquorice, cassia and heracleum spondhylium aka hogweed or cow parsley. The latter, a native of Europe and Asia, is a source of nectar, particularly for pollinators, and is rated in the top ten for nectar production. The botanicals are steamed, rather than boiled, in the Carterhead still, a process designed to capture some of the subtler essences and aromas which might otherwise be lost in a more vigorous process, before being distilled down in natural water to produce the finished product with a very acceptable fighting weight of 43% ABV.

The bottle is squat with rounded shoulders rather than angular, leading to a short neck and a wooden stopper with an artificial cork. The glass at the shoulder is embossed with “Distilled in Hawick” and “The Borders” and at the bottom of the bottle with “The Borders Distillery”. The central label, using a pale green background, names the principal botanicals, but not all, and some of the places Kerr is associated with. It is a classy and elegant design in a rather understated way.

On removing the stopper, the first impression was one of boldness, the aroma an almost heady mix of juniper, herbs and citrus. In the glass and tasted neat, it initially tasted like a traditional London Dry with the juniper and its usual companions to fore. Then the citrus hit before giving way to the more earthy, herby sensations and departed leaving a pleasant, slightly spicy and lingering aftertaste. It was a remarkably smooth drink and with the addition of a mixer some of the subtler tastes and sensations of the herbs seemed to come to the fore.

As a gin, it has quite a strong and distinctive taste to it, although in the back of my mind, I seemed to me I had tasted something like it before. Rifling through my tasting notes, I tracked it down, it tasted rather like an understated Rosemullion Dry Gin. That is not a criticism. After all, even with the diversity of gins and styles that the ginaissance has spawned, there can only be a certain range of botanical combinations that make a quaffable drink.

I enjoyed Border Distillery’s gin and am sure that William Kerr would have approved.

Until the next time, cheers!

December 9, 2020

Book Corner – December 2020 (3)

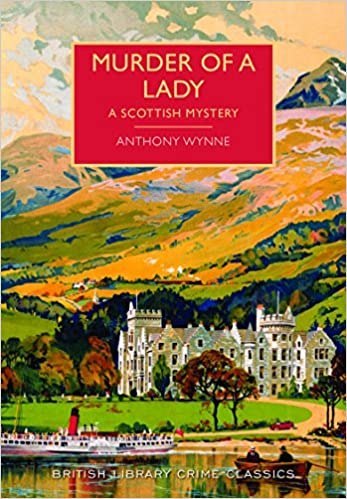

Murder of a Lady – Anthony Wynne

Arthur Wynne was the nom de plume of surgeon, historian, and writer, Robert McNair Wilson. Death of a Lady was published in 1931 and also went under an alternative title of The Silver Scale Mystery. It is Wynne’s twelfth book to feature his amateur detective, Dr Eustace Hailey. Unlike many series of stories featuring a single detective creation, this book stood on its own merits and required little or no knowledge of the detective to enjoy and appreciate it. The book was much more about the plot and a clever story it is too, with an ingenious twist on how to commit a murder or three.

Set in the Highlands of Scotland, Dr Hailey is staying with a friend, Colonel John MacCallien, when they are told that the sister of the local laird, Mary Gregor, has been murdered at nearby Duchlan Castle. It is a classic locked room story, doors and windows locked and a sheer drop from the window. A scale of a herring is found by the fatal wound, prompting the locals to talk of things that swim in the loch and terrorise the neighbourhood. Hailey is made of sterner stuff and is determined to unravel the mystery of how could have committed the murder and how.

Hailey aids and abets the police, but as both of the inspectors seeming to be closing on identifying who the killer might be, or so they think, they are both murdered in circumstances where it would have been thought impossible for a crime to be pulled off. Each has a herring scale by their fatal wound. So, as well as a locked room mystery, you get two impossible crimes for your money.

As investigations get underway the dark secrets of Duchlan Castle begin to be unravelled. As Wynne notes as the story gets underway, “there’s something wrong with this house”. Mary Gregor wasn’t the paragon of virtue that the laird paints her to be but ruled the household with a rod of iron and suppressed anyone who ties to usurp her position. It transpires that the laird’s wife drowned herself and shortly after Mary’s murder, the daughter-in-law, Oonagh, tries to drown herself.

The finger of suspicion falls on the laird’s son, inevitably he is in debt and would benefit financially from his aunt’s death, and his wife, who had a furious row just with the victim just before her death. Hailey, though, is convinced of their innocence and believes that one of the clues to unlocking the mystery(ies) lies in the old scar found on Mary’s body which she had been keen to hide. Of course, it is and does, although I will not spoil your enjoyment by giving anymore away.

Wynne conveys the gloomy, almost Gothic, atmosphere of the castle well and there are not too many red herrings, only their scales, or coincidences to give the story an air of implausibility. It is a well-crafted tale, enjoyable and clever. Wynne takes time to explore the dynamics of the household and get into the mentalities and motives of the various suspects and it pays off. There are some quirky features about the book, not least the suspicions of lowland folk about highlanders and vice versa.

An enjoyable read and a pleasant way to spend a few hours.

December 8, 2020

Covid-19 Tales (15)

Being cooped up with loved ones can cause even the strongest of relationships to fray at the edges, it seems.

An unnamed Italian man from Como had an argument with his wife and decided that he should go for a walk to calm down. Seven days and 280 miles later, he had reached the beach resort of Fano on the Adriatic coast.

Current lockdown restrictions in Italy have imposed a curfew between 10pm and 5 am and a routine patrol by the carabinieri found him out and about at 2am and arrested him. Checking on their database they were able to corroborate the man’s story, his wife had reported him missing, but still fined him €400 for breach of curfew restrictions. They did put him up in a hotel, though.

Despite walking forty miles a day, the man claimed that he was “fine, just a little tired” and reported that strangers had given him food and drink along the way.

Must have been some argument. The couple are reunited and may even be living happily together.

December 7, 2020

Book Corner – December 2020 (2)

A Man Lay Dead – Ngaio Marsh

Published in 1934, this is the first of New Zealand-born Ngaio Marsh’s thirty-three novels to feature her upper-class detective, Roderick Alleyn. I found the book difficult to get into at first and, whilst entertaining enough, was fairly average fare. It had all the hallmarks of an accomplished author getting into her stride and finding her feet.

The first disappointment for me was the plot. The setting is a weekend gathering at an English country house, standard fare for murder mysteries, where the assembled company are going to play a party game called Murder, where one of the guests is selected as the murderer, one of the guests is ”murdered” and the others have to work out who did it. What fun! Of course, the game of “Murder” goes wrong and one of the guests, Charles Rankin, a philanderer, is murdered. Whodunit and why?

The usual motley crew of characters form the Sir Hubert Handesley’s house party. There was an archaeologist, Arthur Wilde, and his wife, Marjorie whose marriage is rocky, a mysterious Russian art expert, Foma Tokareff, Rosamund Grant, Sir Hubert’s niece, the thoroughly modern Millie of a girl, Angela Morton, and Nigel Bathgate, Rankin’s cousin. Throw in for good measure a Russian butler who is a member of a secret cult, an exotic dagger which has connections with a Russian secret society and there is plenty of scope for a feast of ludicrous alibis, outrageous red herrings and a sub plot of Russian gangsters which really adds little to the storyline other than padding it out. And the way that the murder is committed is preposterous, requiring a high level of balance, gymnastic ability, and all carried out in the dark in the matter of seconds.

Although a third-party narrative, the story is seen through the perspective of Nigel Bathgate, a journalist and terribly nice, well-connected young man. Despite a moment of unbelievably surprising amnesia, Bathgate has his alibi confirmed and is corralled by Alleyn to help him establish who the murderer is. The pair are also assisted by Angela Morton whose pluckiness and devil-may-care attitude, she drives at speeds reaching 60 to 65mph for goodness sake, is just what is needed to combat those dangerous Bolshevik gangsters. The developing love interest between Bathgate and Morton also helps to pad out the book.

It seemed to me that Marsh had not quite settled on how to portray Alleyn. At times he reads like a second-hand Lord Peter Wimsey, debonair, not taking himself too seriously, having a rather flippant attitude to the matter in hand. On other occasions he is a more cerebral detective with a nose for things and an ability to spot what others have missed or to see through a miasma of conflicting alibis and motives.

For all his cleverness, Alleyn cannot actually prove how the murder was committed and has to rely upon an amateurish reconstruction of what he supposed happened and a confession from someone whose earlier attempt to confess all he had contemptuously rejected.

I finished the book, thinking that it was surprising that Marsh was considered to stand alongside her earlier female counterparts, Christie, Allingham and Sayers. It was not a bad book, entertaining enough and well written, but even for its time it was somewhat clichéd, bloated and improbable. That said, Marsh does play fair with the reader and the clues are all there to follow Alleyn’s reasoning, if you can be bothered.

Perhaps the other 32 books will be better!

December 6, 2020

Names Of The Week (8)

Hard on the heels of the decision to change the name of the Quebecois town of Asbestos to Val-des-Sources, the 100 or so residents of an Austrian village 350 kilometres west of Vienna have decided to herald the dawn of 2021 with a new name, Fugging.

For a thousand years or so it has been known as Fucking, but the villagers, known as Fuckingers, have grown a little tired of tourists stopping to take advantage of the photo opportunities the signs offer and the ridicule to which they have been subjected. Fugging apparently approximates to the way the locals pronounce the name of the village.

A 6th century Bavarian baron by the name of Focko is said to have founded the settlement and it appears in a map from 1825 as Fuking.

It is not known what the Fuggingers are going to do with all the redundant signs. I would imagine there will be quite a market for them.

And where does the change leave the nearby hamlets of Oberfucking and Unterfucking? Fucked, I guess.

December 5, 2020

Covid-19 Tales (14)

The Danes, having found a mutant strain of coronavirus in their mink population, arranged a cull of more than 10 million of the creatures. They were then buried in shallow, mass graves at a depth of around one metre.

Unfortunately, in West Jutland the bodies are beginning to surface back on the surface, in a zombie stylee. It seems that as the bodies decompose, gases form and push what remains of the creatures up and out of the ground. To counter the problem, the authorities have been shovelling extra soil on to the graves to increase the depth at which they are buried. The soil in West Jutland, it seems, is sandy and at the original depth forms too light a barrier to prevent the rise of these zombie mutants.

There may be another problem. Scientists fear that some of the mass graves were positioned too near natural water supplies and, consequently, that drinking water has been contaminated.

Covid-19 seems to be the disease that keeps on giving.

December 4, 2020

Cantering Through Cant (11)

No gentleman in the 18th century would be seen out in public without wearing a wig. Hair hygiene being somewhat rudimentary, most shaved their pates to rid themselves of greasy, nit-infested locks and a splendid wig hid their baldness. Not unsurprisingly, there was a dearth of synonyms for a wig in the argot of the day. Francis Grose in his A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785) informs us that a cauliflower was “a large white wig, such as is commonly worn by the dignified clergy, and was formerly by physicians”.

Cauliflower, though, also had a different and less obvious meaning, “the private parts of a woman”. Grose explains all by recounting a tale, whether apocryphal or grounded in fact I know not; “a woman, who was giving evidence in a cause wherein it was necessary to express those parts, made use of the term cauliflower; for which the judge on the bench, a peevish old fellow, reproved her, saying she may as well call it artichoke. Not so, my lord, replied she; for an artichoke has a bottom, but a c**t and a cauliflower have none”.

It is fascinating to observe how words change their meaning over time. Take caterwaul. Now we take it to mean to wail or screech like a cat; it has very much a sonic context. However, in Grose’s time caterwauling was defined as “going out in the night in search of intrigues, like a cat in the gutters”.

Clearly, there is more about a caterwaul than making a noise.

December 2, 2020

Wallis’ Locomotive Game of Railroad Adventure

From this time perspective it is difficult to appreciate just how transformative the introduction of the railways. As well as allowing people to travel at previously unimagined speeds, it heralded in social travelling, the weekend as well as opening up the economy and requiring the need for uniformity in time. Inevitably, games’ manufacturers sought to cash in on this railway boom and Edward Wallis was one such. His game, romantically entitled Locomotive Game of Railroad Adventure, was developed and first produced in 1835.

It sought to capture the thrills and spills of a railway journey by way of a game consisting of 49 squares on a beautifully printed board, illustrating stations and locations along the putative route. Dice rather than a teetotum was used, there were now no such concerns about the morality of using something associated with sinful gambling, and as the players navigated their way around the board there were, rather akin to snakes and ladders, hazards which could impede the journey, forfeits had to be paid and, to even things up, the opportunity to gain an extra go..

Reflecting the infancy of the national rail network, the game took the players on a circular journey from and back to London in two geographic loops, although represented as a continuum on the board, taking in Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds, Southampton, Birmingham once more, and York. The winner was the first to get round the course, although I have not been able to establish conclusively whether they had to land exactly on the winning square. Players also seem to have been provided with a certain amount of money to fund the consequences of some of the hazards that lay in store for them or to make their journey more comfortable. Quite how much and what the consequence of running out of money is unclear.

Depending upon the square you landed, you would be required to pay a fare appropriate for the class of accommodation, there were three classes, as well as the Cattle Carriage and assorted carriages for livestock and goods. Then there were squares which might be described as representing the experience of travel. If you landed on a square with a tunnel you received a token from each of the other players “to cheer you when you are travelling in the dark”. Failure to observe the railway companies’ rules and regulations. One square was labelled “Intoxicated” and the player who landed there was ticked off for travelling in such a state. The smoking of a cigar in a carriage labelled “No Smoking” incurred a fine of four. Squares labelled “Refreshment Room” and “Private Carriage” meant the player incurred extra expense while the square entitled “Lazy Lay-a-bed” meant missing a turn as your indolence had caused you to miss the train.

Railway journeys were not without their incidents and the game sought to replicate the real-life experience. Delays caused by the inclemency of the weather – snow, ice, flooding – would hold the player back as well as a stop to replenish coke and water. There were also accidents to navigate. One square was labelled “Pig run over” and if you were unfortunate enough to land there you would be fined one “for letting them stray on the line, one for the poor fellow you have made into pork, and two for that one begun to be converted into sausage meat, by taking off his snout”. Another square had the train hitting a horse. There was no mention of any human fatalities or derailments or boiler explosions which were part and parcel of the real train experience at the time. Swift progress, though, got you to the market first, in time to make a killing. The game, though, did suggest that any profits made should go to charitable causes, a mix of the well-meaning philanthropy that infiltrated some parts of Victorian capitalism.

The game also had its moments of humour, intentional or otherwise. One square pictured a bridegroom, distraught at the sight of the train moving off carrying with it his bride. For this misfortune you missed a turn.

The game shed an interesting insight into the attitudes towards train travel at the time, but in time would prove no substitute for the delights of a model railway.

Book Corner – December 2020 (1)

To Let – John Galsworthy

Going through my library on my Kindle I found that whilst I had read the first two books in Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga, Man of Property and In Chancery, I had not completed the trilogy. Looking for something different from my diet of Golden Age detective fiction, I decided to give the final part, To Let, published in 1921, a go. Galsworthy went on to write another six books about the family he created, but this book brings to an end the story of the old generation with the death of Timothy. I’m not sure the book stands up on its own merits and to enjoy and appreciate it, you need to have read its predecessors.

Perhaps because of this, the book is more immediately engaging than the earlier ones, Galsworthy assuming that his reader is up to speed. The story has moved on twenty years since the bitter divorce of Soames and Irene. Soames has married again and has a beautiful if high-spirited and spoilt daughter, Fleur. Irene too has remarried, to Soames’ cousin, Jolyon, and she has a son, Jon. Inevitably, Fleur and Jon fall in love, an affair that is doomed but one that rakes up the bitter coals of their parents’ past.

Galsworthy’s strengths lie in his easy narrative style and his readiness to poke fun at middle class mores. His characterisation is first rate and setting the unlovable and rather staid Soames at the centre of the book, whilst a risk, pays off. We get to know him, warts and all, and begin to see what makes him tick. His world order is falling apart, his elder relatives are dying off and the youngsters are so different in attitude, living for the moment rather than building a solid portfolio of investments and property, that he cannot understand them. He also concerned that the well-established certainties of life are under attack and looming large in his thoughts is the threat of taxation that will hit his slowly accumulated wealth.

Soames has not got over the loss of Irene, made worse by the fact that she married his cousin and lives in the house he had built for her and which was the start of where their relationship went wrong. The reader can readily understand his despair when he learns that his daughter is pursuing a dangerous liaison. Besotted by her, the only possession that he has that he truly loves, he feels he has to support her, despite the pain it brings him. he death of Jolyon forces matters to a head and Jon has a difficult choice to make. I could not help thinking that he made the right one.

Fleur, of course, was resilient enough to move on and settle down with someone who, at least in her father’s eyes, was a much more suitable match, and came with the prospect of a title, something that the Forsytes had previously looked on with disdain. After all, they were men of substance, measured in bricks and mortars, and pounds and pence, not fancy titles.

The events of the book force Soames to take stock of his life and his philosophy and ends on a rather gloomy note. ““To Let”—the Forsyte age and way of life, when a man owned his soul, his investments, and his woman, without check or question. And now the state had, or would have, his investments, his woman had herself, and God knew who had his soul. “To Let”—that sane and simple creed!”

But it is not a depressing book. The story is well told and plotted, the characters, even the minor ones who flit in and out, are well fleshed out. Imperfections are not hidden. The Fleur Jon storyline could easily have gone into Romeo and Juliet territory but Galsworthy, rightly, resists the temptation and allows the love affair to reach its natural conclusion. With the exception of Timothy’s servants, who are a little too stereotyped for my taste, the characters are painted in a naturalistic style and the reader can believe in them and their motivations.

I enjoyed the book.