Martin Fone's Blog, page 170

January 28, 2021

Death In Ecstasy

Death in Ecstasy – Ngaio Marsh

This fourth Inspector Alleyn novel, published in 1936, is an odd affair and I am still unsure what to make of Ngaio Marsh. For some the characterisation of two of the characters will seem overtly homophobic, capped off by the comment that they could not be the culprits because they wouldn’t have the guts for murder. Also, from a police procedural perspective, it is very odd for Alleyn to spike one of the suspect’s drinks. And then we have the problem of dear old Nigel Bathgate.

At a loose end, Bathgate looks out of the window of his flat on a wet and windy evening and espies a motley group of characters entering the door of a building nearby. His interest piqued, he goes along to see what is happening. He has stumbled upon the House of the Sacred Flame. Refused entry by the doorman, he manages to sneak in and witnesses a bizarre quasi-religious ritual involving the group standing in a circle, chanting the names of gods and passing around a chalice. Would you believe it but the very ceremony that Bathgate chooses to observe ends in tragedy, the “Chosen Vessel”, Cara Quayne, quaffing some poison from the chalice and dying. The newshound rings for Alleyn to investigate.

Bathgate seems to have a nose highly tuned for a story – disaster seems to follow him about – but once he has been used as a plot device to get the story off the ground, Marsh has the problem of what to do with him. Inevitably, he hangs around, adding little to the story and distracting us from Alleyn’s official helpers, Fox and Bailey.

The cast of suspects are a motley crew of eccentrics, all stereotypical in their own way and none of whom Marsh seems to have any sympathy for. The leader of the sect is a conman, Jasper Garnett. A leading light in the movement is an American businessman, Samuel J Ogden. There is a Frenchman, Raoul de Ravigny who was friendly with the victim, Janie Jenkins, the youngest of the group, who is in love with the addict Maurice Pringle. To complete the list of suspects there is an elderly spinster and all-time busybody, Ernestine Wade, and a jealous woman, Mrs Candour.

By fair means or foul, Alleyn tries to sort out what really happened during the ceremony. It all revolves around poison and at least Marsh did her homework, thanking in the preface to the book, Robin Page for his advice on sodium cyanide, and Robin Adamson for “his fiendish ingenuity in the matter of home-brewed poisons”. In truth, the mystery is not too hard to solve when you realise that money is the root of all evil.

It was a moderately entertaining story, but there were too many irritants along the way to make the book anything more than that.

January 27, 2021

Mystery Mile

Mystery Mile – Margery Allingham

I can’t make mind up about this book, a hugely enjoyable romp of a book, first published in 1930 and, whilst technically the second in Allingham’s Campion series, the first where her sleuth takes the leading role. My quandary is whether it should just be seen as an entertaining detective mystery or was it a send up of the lighter side of the genre, particularly Dorothy L Sayers. Campion, after all, is portrayed as an eccentric, somewhat silly individual, whose innocence and seemingly off-the-wall behaviour and questioning disarms even the coldest of criminal heart. Campion is a chip off Lord Peter Wimsey’s block, but one who is dealing with much darker forces with an international reach.

Once again, we are dealing with an international gang – a trademark feature of the Allingham novels I have read to date – who are out to kill Judge Crowdy Lobbett, who has information that could unmask Mr Big. Wherever Lobbett goes, there seems to be a trail of destruction and unfortunate accidents. His associates are killed in bizarre incidents and the fear is that one day they will get the judge. Campion is hired to protect Lobbett.

We first meet the party on board the good ship Elephantine, a liner en route to Blighty. Campion first appears when he sacrifices a mouse he has adopted in the electrified contraption used by Satsuma, a Japanese magician, in his stage act, thus saving the judge’s life. On arrival in England and after another failed attempt, Campion thinks that it is best to hide the judge to a country mansion deep in the wilds of Mystery Mile, a village on an island, probably modelled on Canvey Island.

There are crimes galore, some sinister, some less serious, enough red herrings to stock a fishmonger’s stall and a wonderful array of characters. There is the local vicar, Swithin Cush, who was not all that he seemed and whose death may or may not have been suicide. Then there is the art dealer, Ali Ferguson Barber, who was also on the Elephantine and makes his way to Mystery Mile. He also is not all that meets the eye and turns out to be a very sinister individual.

A Golden Age detective story wouldn’t be a Golden Age detective story without charming, if limited, rustics and a bit of superstitious nonsense involving The Seven Whistlers. Campion weaves in and out of the story, often his whereabouts unexplained and then he suddenly pops up, with a piece of information that keeps the story moving. If you are looking for a methodical Thorndyke or an inspired Holmes, Campion is not your man. It is often difficult to discern how he has got to a particular point in his investigation. That together with some unnecessary but highly entertaining detours do not seem to matter much because the sum of all these parts is a wonderful, page-turning read.

The denouement of the book is a life and death struggle on the edge of the coast between Campion and the Mr Big, Simister, in an echo of the tussle between Holmes and Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls. On the whole, I think it was intended to be a send-up.

January 26, 2021

Haggis Of The Week

To celebrate Burns Night, a haggis has been sent up to the edge of space for the first time, I learned this week.

Working in conjunction with space education and research firm, Stratonauts, a Scottish butcher, Simon Howie, attached a 454g haggis to a weather balloon and let it off. The balloon reached a height of 20 miles above the Earth’s surface with haggis attached and travelled over Stirling, Falkirk, Edinburgh, and the Pentland Hills before landing in Lauder in the Borders.

The haggis survived unscathed, but many would think that a life circling the Earth’s atmosphere would be the best place for it.

January 25, 2021

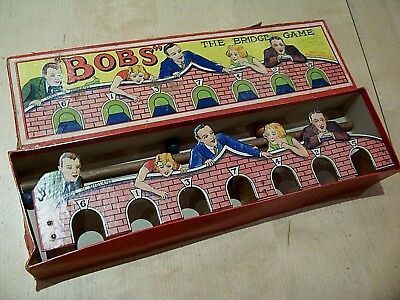

Bob’s Bridge Game

The problem with games such as snooker, pool, billiards, and bagatelle, popular as they may be, is that a full-size table together with sufficient room to enable the players to address their shots from any point means that you need a considerable amount of space to play them. Only the well-off were able to allocate a separate room to which the men could retire after dinner to play a game. The lower orders had to resort to playing in club premises established for the purpose or on smaller versions of the tables in public houses and clubs. As a consequence, opportunities to play at fairs and fetes on outdoor tables were eagerly seized upon.

Indoor games manufacturers realised that there was a ready market for an indoor version of a cue and ball game, if they could only develop one that was relatively simple and space efficient. One such that emerged in the early 20th century was Bob’s Bridge Game, which, if the labelling on the top of the box in which it came is to be believed, was “a popular colonial pastime for any number of players”. It is not clear whether this meant that the game originated from one of the outposts of the British Empire or whether those sent to some far-flung outpost of the empire whiled away their hours playing it.

On opening the box, the players would find a wooden bridge with a number of arches, usually between seven and nine, cut into it. Above each arch was painted a number which represented the number of points you scored if you spotted a ball through it. The bridge had two side flaps which allowed it to stand up. There was also a cue, in two parts which fitted together, usually with red trim and a blue end. To complete the equipment supplied there were seven balls, one of which was red while the others were uncoloured. Regrettably, in early versions of the game the balls were made of ivory.

The game was simplicity itself. You would place the bridge at one end of the table with the side showing the numbered arches facing the players. The red ball would then be place in the centre of the table, about six inches away from the bridge. Taking the cue, a player would strike one of the uncoloured balls with the intention of striking the red ball or any other ball in play and placing it through one of the arches. If the player failed to put a ball through an arch, the ball was left in play and the next player took their shot.

If an uncoloured ball went through an arch, the player scored the number of points allotted to the arch. If they managed to put the red ball through, their score was doubled. If their ball went through an arch without striking another ball, then the points allocated to the arch were deducted from their score. The winner was the one who had the most points when only one ball remained in play.

I wonder how much damage was caused when the balls shot through the arch and fell off the end of the table. A fourth piece of wood, attached to the flaps so that it made an enclosed area, would not only have given the structure extra rigidity but also would have held the balls. This simple solution didn’t seem to strike the manufacturers, probably because it would have made the structure unwieldy for packing into a box of a size that would appeal to shopkeepers.

January 24, 2021

Swan Of The Week

Once upon a time it was fashionable to have three flying ducks hanging on the wall. An elderly woman in Barton-in-Fabis in Nottinghamshire went one better when she had a swan-shaped hole put into her double-glazed bathroom window.

It wasn’t a deliberate choice on her part. A swan, on its way to the nearby River Trent, flew straight at it, smashing it to smithereens and landing in a heap in her room. Fortunately, the woman, who had been standing at the window admiring the view, had stepped away and avoided injury.

The swan, though, was not so lucky and had to be taken away by the RSPCA to be patched up.

It should have gone to Specsavers.

January 23, 2021

Covid-19 Tales (16)

We seem to be having a bit of a BDSM vibe going on this week. News has reached me of another innovative but failed attempt to beat a coronavirus curfew.

Authorities in Quebec have imposed a strict curfew between 8pm and 5am, one of the few exceptions being to walk a dog and then only as far as one kilometre away from your home. Police in Sherbrooke spotted a man and a woman out for a walk at around 9pm on Sunday 10th January.

On closer inspection, the officers discovered that the woman was walking her husband on a lead. They had no truck with the couple’s argument that all the woman was doing was walking her dog of a husband and both culprits were rightly slapped with CAD€1,500 fines.

January 22, 2021

Sparrow-mumbling

Our attitude towards animals has changed for the better over the centuries, although some might say that the organised and indiscriminate slaughter of wild creatures has simply been replaced by the systematic erosion of their natural habitats. What has changed, undoubtedly, is our aversion to acts of cruelty directed at one or more animals, a change in attitudes that led to the passing of the first Cruelty to Animals Act in Britain in 1835. This Act, following lobbying by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, itself formed in 1824, expanded protection afforded to bulls, dogs, bears, and sheep in earlier legislation and prohibited bear-baiting and cock-fighting.

These, though, were not the only pastimes which in 1860 Erastus Benedict called “the kindred manly sports of the lower classes”. Other activities such as badger-baiting and dog-fighting prevailed (and still do, albeit clandestinely and illegally) affording the spectator a dubious form of entertainment and the opportunity to wager on the outcome. These contests were usually fatal to one or more of the contestants. If there was any merit to the bizarre practice of sparrow-mumbling, a pursuit popular at fairs, the odds were slightly in the favour of the bird.

That observer of the language and customs of what were deemed to be the lower orders, Francis Grose, included a description of sparrow-mumbling in his Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, first published in 1811. Even by the standards of the time, he felt moved to call it “a cruel sport”. What he called a “booby”, a stupid or silly person, paid a fee to participate in the contest. His hands were tied behind him and “the wing of a cock-sparrow put into his mouth: with this hold”, Grose explains, “he is to get the sparrow’s head into his mouth: on attempting to do it, the bird defends itself surprisingly, frequently pecking the mumbler till his lips are covered with blood and he is obliged to desist: to prevent the bird from getting away, he is fastened by a string to a button of the booby’s coat”.

Grose’s description was of a version of the pastime practised in London, but there were other variants. In Cornwall miners would attempt to strip the feathers from a sparrow by just using their teeth, after the unfortunate bird had been tethered by a string to their teeth. A more extreme version was to clip the bird’s wings and place it in a hat. Using just their lips, the contestant was supposed to manoeuvre the bird into their mouth and bite its head off.

One of the earliest references to the custom appeared in George Chapman’s Andromeda Liberate from 1614. There he writes how it was “most pleasing to sit in a corner and spend your teeth to the stumps in mumbling an old sparrow till your lips bleed and your eyes water”. In the 18th century one of John Arscott’s party pieces, when entertaining at his family pile of Pencarrow, was to put a live sparrow into his mouth and using his teeth to pluck all its feathers off. His guests were invited to guess whether it would fly again. He would also swallow a live mouse and regurgitate the creature from his stomach. Not to be outdone, Francis Delaval once “organised a great contest of sparrow-mumbling for his friends”.

The practice fell into disfavour in the 19th century.

January 21, 2021

Mayfield Sussex Hop Gin

One of the fascinating features of the ginaissance is how enterprising distillers have sought to introduce new botanicals into our favourite spirit. It creates a marketing edge, an opportunity to differentiate yourself from the crowd and sometimes it even produces a drink that is memorable and worth the effort. James Rackham’s idea was to use the Sussex hops that he found growing wild in the hedgerows as the central component of his new gin. The result was Mayfield Sussex Hop Gin. As gin and beer are my favourite tipples, a gin that combines the two has got to be worth investigating.

The Sussex hop is now an approved variety of hop and rather than relying on the variable bounty of the hedgerows, Rackham secures his supply from a hop farm in Salehurst. It is one of eight botanicals used in the mix, bringing with it some heady floral tones and characteristic bitterness. I was concerned that the taste of hop would overwhelm the gin, but Rackham has guarded against this with a judicious choice of accompanying botanicals. To watch over the hops he has chosen juniper, orange peel, lemon peel, angelica root, coriander, liquorice, and orris root. Each of the botanicals is micro-distilled in a copper pot still and then brough together. Bar the hops, it is a very conventional line up and one that would normally result in a tasty, traditional London Dry gin style.

Indeed, that is the case. On opening the synthetic stopper, the aroma is distinctively juniper led with hints of citrus and pepper. In the glass the spirit is crystal clear. In the mouth, the first impressions are of a hit of juniper followed by some citrus elements, although more subdued in taste than in smell, and pepper. The aftertaste is lingering with a warming mix of juniper and spicy pepper. The hops, frankly, are difficult to detect, operating in the background to give a hint of floral tones, rather than dominating the spirit. It is a well-balanced, indeed elegant, gin and with an ABV of 40% has enough kick to make its presence felt while leaving room for more. It left me thinking, though, it could have been a little more adventurous in allowing the hops to assume more prominence.

The bottle is attractive, made with clear glass, looking rather like a slightly dumpy wine bottle. What makes it stand out on the shelf is its diabolic label featuring an image of a startled devil with a pair of tongs wrapped round his nose. This relates to the epic struggle between St Dunstan and the devil, played out in the 10th century in the village of the gin’s origin, Mayfield. Archbishop Dunstan is said to have grasped the devil’s nose with a pair of red-hot tongs and the devil’s roar was heard three miles away. The very same pair, it is said, were displayed at the village’s convent.

The devil went off to the nearby springs in Tunbridge Wells to assuage his heated nose, thereby giving the waters their distinctive reddish hue, although in reality this is down to its high iron content. Another version of the story claims that the devil flew off towards Brighton with the tongs still attached to his nose and they dropped off and landed at a place now known as Tongdean.

All nonsense, of course, but it adds a nice marketing edge to what is an impressive gin and a welcome addition to my collection.

Until the next time, cheers!

January 20, 2021

The Puzzle Lock

The Puzzle Lock – R Austin Freeman

Another collection of short stories, nine in all published in 1925, showcasing the talents of R Austin Freeman’s detective creation, Dr Roger Thorndyke. Through the eyes of his faithful scribes, principally, but not exclusively, Jervis, the reader has the opportunity to wonder at the observational skills and deep scientific knowledge that Thorndyke deploys to crack what otherwise seem intractable problems.

I had read a couple before in anthologies, Mystery of the Sandhills and the Green Check Jacket, but that did not spoil my enjoyment and it was interesting to seem them in the context of this collection. The problem I find with Freeman is that he is a bit dry as a writer, scrupulously fair with the reader in explaining the intricacies of the cases and determined to reveal the depth of Thorndyke’s forensic knowledge, whereas some of the stories could do with a bit of Conan Doyle’s lightness of touch, even if the latter comes at the expense of probability and credibility.

The eponymous story opens the collection and Thorndyke in attempting to solve the mysterious disappearance of two men and a robbery, finds himself and his colleagues in a tricky hole. In order to escape with his life he has to crack the code to an ingenious chronograph lock. That there are eight further tales rather suggests that he succeeded.

Thorndyke’s ability to analyse dirt and chalk comes in handy in solving the complexities of the Green Check Jacket and, in particular, in placing the murder spot, while his understanding of the peculiarities of walking sticks leads to the resolution of the conundrum that is Nebuchadnezzar’s Seal. Mystery of the Sand Hills revolves around footprints made in the sand and the dunes.

Rex v Burnaby is an unusual twist on the usual tales as Thorndyke is trying to prevent a murder. A man is extremely sensitive to a particular drug that appears to be poisoning him. However, it is almost impossible to fathom out how the drug is being administered to him. Cue, Roger Thorndyke. In a similar vein, Apparition of Burling Court involves a man who believes that a curse has been responsible for the deaths of some of his ancestors and that he is next on the list. Will Thorndyke solve the case in the nick of time?

He has his work cut out to defend his clients in Phyllis Annersley’s Pearls as two witnesses to the woman’s murder positively identify them. All is not lost, though.

Money is a powerful motive for murder and that is the theme behind The mysterious visitor. The disappearance of a man is barely cause for concern until it is discovered that he has inherited a large fortune. He needs to be found and, quite how did the legatee die? The premise to the Sower of Pestilence is a little bizarre in that a man running a cats’ orphanage receives a large donation in the form of a purse that has clearly been stolen. A bank is then bombed. Are the two incidents linked? Thorndyke, of course, reveals all.

As the solicitor remarks at the end of Phyllis Annersley’s Pearls; “and yet it is so obvious – when you know”. A book to dip in and out of if you like cases of a more technical nature.

January 19, 2021

Hack Of The Week

The world of BDSM has been rocked by a glitch that has left many participants hacked off. Chastity belts are popular as a way for a dominant to control their submissive partner from touching their own genitals and to use them to engage in sex. It is the way of the modern world that some innovative company, Qiui Cellmate in this instance, have jumped on this predilection and produced an electronic chastity belt which is controlled by an app, the first in the world, they claim.

Unfortunately, the manufacturers were not as careful at safeguarding the password that protected their coding from harm as they were their clients’ genitals. Some bright spark has managed to break into the device, sending threatening messages to the wearers, demanding money. Failure to pay up would see them being stuck with the device forever.

One victim who received a demand for AUD$900 was shocked to see that the hacker wasn’t mincing their words. The software in the lock had been tampered with and he could not open it. Fortunately, as he did not have the device on, a heavy-duty bolt cutter or angle grinder was not needed to cut the metal ring which locks the device under the wearer’s penis.

Moral of the story – trust your partner, not software.