Martin Fone's Blog, page 154

June 27, 2021

Orchid Of The Week

Where’s the safest place to keep something away from prying eyes? A bank, obvs.

The small-flowered tongue orchid, Serapias parviflora to you and me, was thought to have been extinct in the UK after the previous colony at Rame Head in Cornwall was destroyed in 2009 as a result of land mismanagement. Normally a native of the Mediterranean basin and the Atlantic coast of France, Spain, and Portugal, it has been found in the roof garden above the 11th floor of the Nomura bank in London’s Angel Lane.

There are fifteen of them and they grow up to 30 centimetres in height and produce between three and 12 orange flowers. I hope they flourish.

Of course, the discovery raises the question: why did it take so long to find them? And is the roof garden just a piece of virtue signalling that no one takes any notice of?

June 26, 2021

Covid-19 Tales (21)

In a considerable step up from encouraging people to give health workers the clap, Nederlands Visbureau, the Dutch Fish Marketing Board, have given the first barrel of 2021 Hollandse Nieuwe, the season’s first herring, to the Municipal Health Services in recognition of their endeavours in the country’s attempts to vaccinate its populace.

Hollandse Nieuwe are young herring caught between mid-May and mid-June that have a body fat percentage of at least 16%. Gutted and salted, but with the pancreas intact, they are eaten raw, held by the tail and dropped into the mouth rather like a seal does its food. The Dutch consider it a delicacy, washing it down with a special liqueur.

I remember a Dutch broker colleague of mine inviting me to celebrate Flag Day in Scheveningen, outside of Rotterdam, a day dedicated to celebrating the arrival of the fishy delicacy. It turned out to be a weekend of nothing but herring. I have never had one since.

After the official handover, herring will also be presented to any vaccination staff and to people receiving their vaccinations at the time. Barrels will also be distributed to other vaccination centres around the country.

If that doesn’t drive up vaccine take up, I don’t know what will!

June 25, 2021

The Devil’s Dictionary (7)

Happiness, according to Ambrose Bierce in his The Devil’s Dictionary, first published in book form in 1906,”an agreeable sensation, arising from contemplating the misery of another”. Some believe that the ultimate form of happiness is to secure a place in Heaven where “the wicked cease from troubling you with talk of their personal affairs, and the good listen with attention when you expound your own”. To help you on your way, you will travel in a hearse, “Death’s baby-carriage”, and mourners may even wring their hands, “a singular instrument worn at the end of the human arm and commonly thrust into somebody’s pocket”. Handkerchiefs may even be evident, although the sage warns that these small squares of silk or linen are “used in various ignoble offices about the face and especially serviceable at funerals to conceal the lack of tears”.

Such consolations, Christians may judge, are unattainable to the heathen, a “benighted creature who has the folly to worship something he can see and feel”. An expression of hatred, perhaps, “a sentiment appropriate to the occasion of another’s superiority”.

Homicide, or murder as we British like to call it, is “the slaying of one human being by another. There are four kinds of homicide: felonious, excusable, justifiable, and praiseworthy, but it makes no great difference to the person slain whether he fell by one kind or another – the classification is for the advantage of the lawyers”.

For all of his forthrightness, at least Bierce was not a hypocrite; “one, who professing virtues that he does not respect secures the advantage of seeming to be what he despises”.

June 24, 2021

Much Dithering

A review of Much Dithering by Dorothy Lambert

This is a lovely book, set in an archetypal quaint English village called Much Dithering. It is quiet, so quiet that it is off the bus route, a comment that would evoke no surprise these days when the range of public transport is so lamentably poor, but at the time the book was published, 1938 and now reissued by Dean Street Press under their Furrowed Middlebrow imprint, it was the epitome of isolation. Nothing much happens in the village and its residents live out their lives following a cycle of humdrum, albeit worthy, activities.

The heroine of the story is Jocelyn Renshawe, a young widow whose husband died a year before his father, thus robbing her of the opportunity of inheriting the family pile, which, when Lady Augusta topples of her mortal coil, will pass to a nephew no one knows and who is living abroad. Jocelyn’s marriage was a loveless affair and she has never known romance and is never likely to. Her aunt and mother-in-law are anxious to settle her long-term future in a way which will trap her in Much Dithering and crush what remains of her spirit.

Much to the disgust of the older residents, some newcomers have discovered Much Dithering including the dull, retired army man, Colonel Tidmarsh, whom the old ladies consider suitable marriage material for Jocelyn, and the nouveau-riche Murchison-Bellabys. Jocelyn’s estranged mother, Ermyntrude, descends on the village for an impromptu stay, less to see her daughter whom she treats with contempt, but rather to continue her dalliance with Adrian Murchison-Bellaby. He, though, not only has eyes for Jocelyn, but is entangled with a young beauty, Lucia, who turns out to be the daughter of the local publican. Adrian’s sister, Joyce, has the hots for Lucia’s brother, the dance band leader, Victor.

For such a seemingly dull woman, Jocelyn finds herself with three suitors, the third being the dashing Gervase Blythe, who seems to be a commercial traveller, an army acquaintance of Colonel Tidmarsh, and gallantly rescues her from a soaking. He is a man of some mystery, although the perceptive reader will have little difficulty in working out who he might be.

The villagers, though, are less perceptive and suspect that he may be a thief as there have been some jewellery thefts in the village, something unheard of in such a backwater, around the time of his precipitate departure. After a trip to the Hunt Ball Jocelyn realizes she is in love with Gervase, but his departure and the odium surrounding his name places her in some difficulty, and she feels she cannot give him the alibi that would clear his name.

Inevitably, this complex web of romantic liaisons resolves itself with each of the main protagonists fated to a relationship which even the most churlish of readers would hope would be their lot.

Lambert has an easy style and writes with some wit and warmth, enjoying the opportunity to poke fun at the insularity of country life and the wariness and positive dislike exhibited towards newcomers and their modern ways by the established village folk. It is also a commentary of the lot of a woman who has to struggle to win her freedom and to live the life that she wants to live rather than the one that her elders allot to her. After much dithering, Jocelyn breaks free.

More than that it is a gentle, slightly whimsical tale which is ideal for a holiday read or if you just want to get away from it all.

June 23, 2021

Helen Passes By

A review of E R Punshon’s Helen Passes By

This is the twenty-third book in Ernest Punshon’s Bobby Owen series, originally published in 1947 and reissued for a modern readership to discover by Dean Street Press. I am a fan of the series, but this was a strange affair. It started off at pace and was bright and breezy in style but soon got bogged down as a result of its rambling and over-complicated plot. It managed to get back on track as it approached its denouement which was as dramatic as it was tragic.

The eponymous Helen is the daughter of Lord Adour, a narcissistic woman who is in love with her own beauty and who has an unerring knack of making men swoon on seeing her. It this power and magnetism that is at the centre of the case, although Owen never gets to see her to test whether he was impervious to her charms.

Counterbalancing this 20th century Helen of Troy is Alexander Wayling, described as “ugly” but who has a charming way that works well with the women and a happy of knack of touching everyone he meets for a few shillings or a few pounds. He manages to relieve Owen of five shillings and Olive of a fiver. The paths of Helen and Wayling become entwined with tragic consequences for at least one of the two.

One of Wayling’s more endearing characteristics is that he is a fount of all knowledge. At the start of the book, he tells Owen that he is to be seconded back to Scotland Yard to head up a politically sensitive case involving the murder of Itter Bains, found shot in the woods, which has been badly handled by the local Deputy Chief Constable, Seers, and which is attracting considerable interest in the left-wing press because of the potential involvement of a prominent peer, Lord Adour, Helen’s father.

And so it comes to pass. Steer has made a pig’s ear of the investigation, mainly because he too is besotted by Helen and cannot conceive of the idea that a noble peer of the realm or his family could be involved in anything as unseemly as a common or garden murder. Owen is the manifestation of Punshon’s egalitarian Weltanschauung, and not only does he believe that such sentiments are nonsense, but he will also treat everyone on their merits. And so he does.

Steer’s preconceptions and bungling of the case means that there is precious little in the way of physical evidence for Owen to work on. It becomes more of a psychological investigation as he strives to understand each character’s motivation and the reasons for their often strange and incomprehensible behaviour. There are many red herrings and oddities including a Frenchman who suddenly appears and then disappears, a motor launch that suddenly vanishes, a well-informed journalist lurking around, the ever-present Wayling and a midnight assault.

One almost irrelevant episode, the boarding house run by Mrs Mack where those who have run the course of their life quickly exit and young women make short sojourns, which whilst answering why the journo Harry Haile is in the area, raises more questions than it answers. Whilst Owen clearly disapproves of the practices of euthanasia and abortion, both illegal at the time that the book is set, which Mrs Mack freely admits are practised there, would a serving policeman turn a blind to it, whether it was within his jurisdiction or not?

As Owen is staying away from home, Punshon finishes several chapters with extracts from the letters Owen writes to his wife, Olive. This allows Punshon to explain Owen’s thought processes at different stages of the investigation and is quite an effective device, even though Punshon resists the temptation to use it to give us some insights into their relationship.

It would not be a Punshon story without a couple of set pieces. They are effective and dramatic, but Punshon’s writing changes from an easily flowing, almost conversational, style to an overly wrought, almost stilted narrative. The disruption to the flow I this book is quite noticeable.

Although this is not one of Punshon’s best, a moderate to good Bobby Owen story has enough in it to keep the reader interested and the ending is well worth persevering for.

June 22, 2021

The Cornish Coast Murder

The Cornish Coast Murder – John Bude

Published in 1935, The Cornish Crime Murder marks the crime writing debut of John Bude, the pen name of Ernest Elmore. He went on to write thirty in total and was a co-founder of the Crime Writers’ Association. His principal detective creation was Inspector Meredith, although he does not feature in this novel. Indeed, the main representative of the police force here, Inspector Bigswell is all at sea in this case and has to be steered in the right direction by an amateur sleuth, the detective fiction loving Reverend Dodd. The book has been reissued for a modern readership to enjoy as part of the enterprising British Library Crime Classics series.

If you like cosy, entertaining murder mysteries which are written with a light touch and literate, this will suit you down to the ground. Bude never reached the heights of some of his contemporaries, perhaps because there is a sense that he does not take things too seriously, preferring to construct an undemanding, unsensational puzzle laced with a gentle sense of humour. I have only read three of his books, so far, but |I have enjoyed them all.

This story, as the title suggests, is set on the Cornish coast in a village of some 400 souls, Boscawen. The book opens with the local vicar, Dodd, hosting his usual cosy Monday evening dinner with the local doctor. The highlight, after a meal, is to go through the latest consignment of murder mystery stories they have received and quizzing each other on their respective success in unmasking the culprit. By the end of the book Dodd has an epiphany, his close association with murder sating and extinguishing his appetite for any form of murder most literary.

Their pleasant evening is interrupted on a night of a fierce thunderstorm when a telephone call from Ruth Tregarthan summons the doctor to the home of her uncle, Julius. He has been found dead in a room overlooking the coastline, shot by one of three shots that have penetrated the window. The three bullet holes show a very erratic shooting pattern. Ruth had been out at the time of the murder and her footprints are found on the coastal path along with those of the local midwife. Ruth’s paramour, Ronald Hardy, had an argument with Julius shortly before his death, the uncle was trying to end the liaison, and has disappeared without trace. As he is suffering from shell shock the finger of suspicion is levelled at him, possibly in cahoots with Ruth, at least as far as the police are concerned.

For the local inspector, Bigswell, this is a rare opportunity to shine and make his name, especially if he can wrap the case up before his superiors are forced to call in Scotland Yard, the experts as he pejoratively calls them. Bigswell is nothing if not thorough but all the leads he follows seem to lead to dead ends. Dodd, pinning his faith on intuition, convinced that neither Ronald nor Ruth was responsible, intrigued by the absence of any other footprints and the erratic nature of the gun shots and a letter that seems to suggest that Julius has a hold over someone going by the initials of ML, eventually pieces all the clues together and uses a rather Heath Robinsonish method to establish where the bullets were fired.

I’m not sure that Bude plays quite fair with his readers when unfolding the solution to the crime I that even if they could identify the killer, there was no way that they could have identified who ML was or what the motivation for the murder was. That said, it was an excellent story and makes an ideal read for a summer holiday, preferably down in Cornwall.

June 21, 2021

Five Exclamation Marks, The Sure Sign Of An Insane Mind

The late, lamented Terry Pratchett may have had a point. Is there are more controversial punctuation mark used today? Elmore Leonard wrote that “you are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of Prose” while F Scott Fitzgerald likened their use to laughing at your own jokes. I try to ration my usage of them but on social media it is often a rarity to see a message without one.

Those who have had the joy of reading ancient texts will know that they were written in scriptio continua, with all the words running into each other without a break. This meant that not only did the person looking at the text have to be able to read but also know enough grammar to be able to make sense of the string of letters before them. It was not until the 6th century that certain literary conventions that we take for granted such as spacing between words and elementary forms of punctuation began to be introduced. The exclamation mark emerged sometime after that.

In Latin, Io means joy. Perhaps to bring a bit of joy into their lives, medieval scribes would put the “I” above the “o”. Over time the “o” became a dot and, lo! the exclamation mark was born. It is difficult to date precisely when the exclamation mark was used purely to add emphasis to a word or sentence rather than being shorthand for “Io” but the earliest example of the mark can be seen in a manuscript written by Coluccio Salutati in 1399. Some think that it was the Italian poet, Iacopo Alpoleio da Urbisaglia who came up with the idea of the exclamation mark slightly earlier in the 14th century, giving it the name of punctus admirativus, the admiration mark.

Grammarians used the term as the designated name for this form of punctuation until some time in the 17th century when the exclamation mark emerged as an alternative descriptor for the punctuation mark. By the 18th century, though, there began to emerge a subtle differentiation between the occasions when the mark would be called an “admiration mark” and when it was more appropriate to deem it an “exclamation mark”.

According to James Hoy, the note of admiration was used for circumstances which “intimated some sudden passion of the mind” while a note of exclamation was reserved solely for “crying out”. We can perhaps deduce from this that the principal distinction between the two was that between joy and anguish. When the mark was associated with rapture, amazement, and wonder it was termed “admiration” but its use in association with disgust, grief, and anger marked it out as the mark of exclamation.

Such subtleties may have kept the grammarians and pedants happy, but for the majority of people this rather contrived distinction served no necessary purpose as whether they exclaimed in joy or anger they were exclaiming. By the end of the 19th century exclamation had won out over admiration, the Stanford Dictionary of Anglicised Words and Phrases noting in its 1892 edition that the note of admiration is “now called the note of exclamation”. All that was left was for “note of” to drop out of use to be replaced by “mark”.

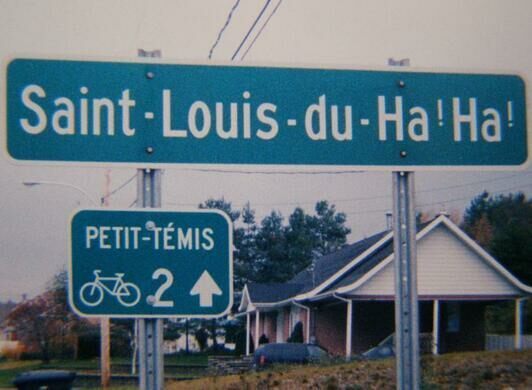

Controversial as the use of exclamation marks may be to some, places such as the North Devon village of Westward Ho! and the gloriously named Quebecois village of Saint-Louis-du-Ha!-Ha! Are proud to display the exclamation mark. Saint-Louis is the only place in the world to use of them, whether in joy or anger I know not.

Love ‘em or loathe ‘em, they are here to stay!

June 20, 2021

Rescue Of The Week

This blog is not known for its sentimentality, but I could not resist this story from Harrison Township in Michigan.

The Fire Department were called to a road junction where a raccoon was seen sticking its head through a hole in a sewer cover. Onlookers were quick to spot that it was stuck fast.

Reluctant to use an oxy acetylene cutter and a liberal application of soap to the hole and the animal’s head not doing the trick, the fire crew borrowed some cooking oil from a neighbour. After oiling the sewer cover and the raccoon, they lifted the cover out and with one officer holding the raccoon’s head and the other pulling its body, they eventually got it free.

The raccoon, unhurt, was liberated after its moment of fame. It made a change from rescuing cats from trees, I suppose.

June 19, 2021

Statue Of The Week (5)

Italian artist, Salvatore Garau, caused a bit of a stir in art circles when his latest masterpiece entitled Io sono sold at auction for €15,000, almost double its reserve price. All the buyer got for their money is a certificate of ownership because the piece is an “immaterial sculpture”, a vacuum.

Explaining his concept, Garau commented that “a vacuum is nothing more than a space full of energy, and even if we empty it and there is nothing left, according to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, that nothing has weight”.

This unusual masterpiece comes with some unusual specifications. It must be displayed in a private home free of obstruction, in an area measuring five feet square. There are no requirements for lighting or climate control.

Gaura’s imagination knows no bounds. In February he unveiled Buddha in Contemplation in the Piazza Della Scala in Milan, an invisible sculpture whose only presence was a taped area on some cobbles. Outside the New York stock exchange, he has installed Afrodite Cries, the only physical evidence of which is an empty white circle.

The artist is challenging us to activate our imagination to see his work. Others might just see it for what it is, but, hey, that’s modern art. I must have hundreds of immaterial sculptures in my house. That will add to its value when I tell the estate agent.

June 18, 2021

The Devil’s Dictionary (6)

Another dip into Ambrose Bierce’s fascinating The Devil’s Dictionary, first published in book form in 1906. We all claim to have friendships, but some are more durable than others. Perhaps no wonder if Bierce’s definition is to be believed. Friendship, he claims, is “a ship big enough to carry two in fair weather, but only one in foul”. To be reduced to a state of being friendless means that you have no favours to bestow, are destitute of fortune and addicted to utterance of truth and common sense.

One reason for being bereft of friends is that they have all died. A funeral is an opportunity to pay our last respects, but in Bierce’s eyes it is “a pageant whereby we attest our respect for the dead by enriching the undertaker, and strengthen our grief by an expenditure that deepens our groans and doubles our tears”. Still, we can always look to the future, “that period of time in which our affairs prosper, our friends are true and our happiness is assured”. Of course, the future never comes.

In the days before fountain pens, biros and the now ubiquitous keyboard, people used to write with quills made from the feathers of a goose. Bierce defines a goose as a “bird that supplies quills for writing. These, by some occult process of nature, are penetrated and suffused with various degrees of the bird’s intellectual energies and emotional character, so when inked and drawn mechanically across paper by a person called an “author”, there results a very fair and accurate transcript of the fowl’s thought and feeling. The difference in geese, as discovered by this ingenious method, is considerable; many are found to only have trivial and insignificant powers, but some are seen to be very great geese indeed.”

If Bierce’s theory us correct, relatively few geese are proficient in grammar which, he notes, is “a system of pitfalls thoughtfully prepared for the feet of the self-made man, along the path by which he advances with distinction”. Indeed.