Martin Fone's Blog, page 153

July 7, 2021

Murder At Fenwold

A review of Murder at Fenwold by Christopher Bush

Also known as The Death of Cosmo Revere, this is the fourth of Bush’s Ludovic Travers series, there are sixty-three in all. Published originally in 1930 it has been reissued for a modern audience to discover by Dean Street Press. I found it hard going in places, more so than with the other of Bush’s novels I have read, and once I had got to the end, I wondered why that was.

Part of the problem, I think, is that the pace of the narrative is quite variable. It starts off at a cracking pace with the narration of a strange and seemingly unrelated contretemps in London and then the death of the local squire and owner of Fenwold Hall, Cosmo Revere, who seems to have been killed by a falling tree which he was felling late at night. The book then slows right down as Travers and John Franklin, the head of the private detective agency at Durangos, who have been appointed to dig into what has been going on at Fenwold by Revere’s solicitor, proceed with their investigations before revving up again towards the end.

The structure of the book is not helped by Travers’ and Franklin’s roles. They are acting undercover, there is no police investigation as such as the authorities are convinced that Revere’s death was a tragic accident, and have to ferret out information while maintaining their façade of master (Travers) and confidential servant (Franklin). It also does not help that Travers and Franklin approach the problem from different angles and keep much from each other as they pursue their pet theories. This makes for a tangled narrative.

The plot also seems unnecessarily complicated. Naturally, Revere’s death is not all that it seems. Some tell-tale yellow sand and the cut of the felled tree suggests that the official version of events is incorrect. We are treated to a discourse on tree felling, complete with diagrams, to demonstrate that Revere had not been the architect of his own demise. The truth is even weirder. He was crushed by a stone, an extraordinarily bizarre and overly convoluted way to hasten his meeting with his maker.

That is not all, though. There are some odd things going on inside the house, principally the replacement of some of the valuable books, artefacts and objets d’art at the house with copies. Who is responsible and has it anything to do with the murder of Revere. An important witness is also done away with. Signalling, a hastily constructed rock garden, a production of Sheridan’s The Rivals and the mysterious duo of Castleton and Carter, never seen together, an invalid nurse and an omnipresent vicar all add spice to the mix. And does that strange encounter in London provide a clue to the real identity and character of one of the protagonists?

Despite my concerns with the book, there are some considerable saving graces. Bush writes with wit and also with feeling for a country life that even then was fast disappearing. It may be seen as a traditional country house murder but Bush goes out of his way to extend the trope and to imbue it with his love for the English countryside and its way of life. That he struggles to pull it off should not detract from that laudable ambition.

There was enough in the book to persuade me to continue with the series. I just hope that the next one is more satisfying.

July 6, 2021

The Creeping Jenny Mystery

A review of The Creeping Jenny Mystery by Brian Flynn

After a bit of a dip in the last outing, the Creeping Jenny Mystery, originally published in 1930 and now reissued by Dean Street Press, sees Brian Flynn back on form. The seventh in his Anthony Bathurst series, the eponymous Creeping Jenny is not the invasive plant that I spend too much time trying to eradicate from my garden but a jewel thief who visits stately homes, relieving its occupants of just one item of jewellery and leaving a calling card-cum-receipt. You just don’t get that class of thief these days. The title of the American edition published two years later, The Crime at the Crossways, is rather more prosaic but at least fixes the action to the home of Henry Mordaunt KC.

Bathurst himself barely features in the story and much of the burden of detection falls on Peter Daventry, his friend, and his old sparring partner, Inspector Baddeley whom we met in The Billiard Room Mystery. Daventry has toned his act down several notches since Invisible Death but is still a bit of a public school ninny who has an amazing ability to miss the obvious and an uncanny knack of failing to recognise familiar faces. We have a couple of outbreaks of dialogue straight out of the Bertie Wooster lexicon when he writes to Bathurst but the absence of Bathurst generally seems to have a calming effect on him, which is no bad thing.

Another character, Russell Streatfeild, also does some amateur sleuthing and he seems to have much more success at unearthing vital clues than anyone else. Apart from being a confidant of Mordaunt and a lawyer for a firm that has long since been dissolved, no one knows anything about him. I will not spoil the fun of the story but I have always made it a rule in life never to take anyone who misspells field at face value. Baddeley, of course as the police often do, jumps to the wrong conclusions and fails to make much headway in solving the crime.

There are two crimes to solve, which may or may not be linked, the theft of the Lorrimer sapphire and the murder of Olive Mordaunt, who was found down a well, stabbed with a dagger, a theatre prop brought to the house by a guest to the house party to celebrate the engagement of Captain Lorrimer to Molly Mordaunt. The theft of the jewel followed the script of previous Creeping Jenny heists with one significant exception. Mordaunt had prior warning that the theft would be attempted.

Prior to the discovery of theft two of then guests very publicly struck a wager of £100 as to whether Creeping Jenny would strike. What was the significance of that? Lorrimer had taken the precaution of secreting a fake sapphire, but that too was stolen. And was it significant that four of the guests had been at each of the house parties where Creeping Jenny had previously struck? And why was Olive Mordaunt lured outside to her death? What did she know that led to her demise? Who was the mysterious person in a yellow dress?

Baddeley, of course, arrests the wrong person but between them Daventry and Streatfeild with some epistolary words of advice from Bathurst work through the clues and piece the puzzle together. It is an amusing romp of a story with a bit of cross-dressing thrown in and a denouement that comes slightly left field in a restaurant in London involving a bit of impersonation and a fist in the face for Baddeley. Still, he made his arrest.

It was a thoroughly entertaining novel, which even Daventry’s occasional lurch into Woosterism did not spoil. If you like your crime novels to have a light touch and entertain, this one is for you.

July 5, 2021

As Ugly As A Tick On A Dog’s Belly

The semicolon is not everybody’s cup of tea. Mark Twain may have been dismissive of their appearance, but in Huckleberry Finn he used 1,562 of them. Herman Melville loved them, peppering his text of Moby Dick with over four thousand semicolons, an average of one for every 52 words. How did this Marmite of punctuation marks come to be used in the first place?

The culprit or hero of our story is a printer who operated in Venice towards the end of the 15th century, Aldus Manutius. Not only was he an accurate printer but he was also innovative. He was the first to perfect the printing of the Greek alphabet, enabling the classical texts of the likes of Plato and Aristotle to be more easily replicated. Manutius’ conquering of Greek script cemented the roles of Plato and Aristotle in Renaissance thought and scholarship.

Manutius was also responsible for developing Italic fonts, where the letters lurch rather drunkenly to the right. In his day books and documents were unwieldy and large, barely portable and meant that readers had to go to the books rather than books accompanying the reader. Manutius’ third innovation was to create the Octavio paper size for printing, essentially the traditional flat sheet folded into half, then half again and then half again, so that it was an eight of its original size. The age of the portable book had dawned.

Punctuation was a rather hit and miss affair. For centuries manuscripts had been written in scriptio continua, where all the letters and words formed one continuous stream, only broken when the scribe reached the end of the line or page. Anyone who has read a mediaeval text, I had to as part of my third year at university, will know that it is a slow and laborious task to extract any meaning from a long line of letters, leaving aside any scribal errors. Manutius realised that the power of printing opened up a wider audience for his products but that readers needed an easier and quicker way of making sense of the jumble of letters on a page and so set about introducing and standardising punctuation.

The semicolon first made its appearance in 1494 in a literary Latin text called De Aetna, printed by Manutius, written by Pietro Bembo and using a hybrid mark, a full stop sitting above a comma, produced especially by the Bolognese type designer, Francesco Griffo. The book, De Aetna, was an essay written in dialogue form about climbing the Sicilian volcano. The semicolons were used primarily to separate long lists of items.

Mind you, there was room for confusion. The same symbol is also used as an abbreviation for -ue in the conjunction neque, meaning “and or also not”, although it is positioned at the same level of the words on the page to show it is not a pause.

Seen as something halfway between a full stop which brings a sentence to a conclusion and a comma which indicates a small pause in the flow, there were no hard and fast rules governing the use of a semicolon. The playwright, Ben Jonson, had a go at defining its use, calling it “a distinction of an imperfect sentence, wherein with somewhat a longer breath, the sentence following is included”. Over time its usage settled down to providing assistance with a long list of items and to allow two ideas, concepts or sentiments to flow together into one sentence as they would into your mind. Its heyday was in the 19th century, but nowadays editors try to discourage its use.

The semicolon has caused some trouble over the years. A dispute over its usage between two University of Paris law professors in 1837 was settled by a duel. A rogue semicolon which entered the transcription of a statute led to the suspension of alcohol service in Boston for six years due to the ambiguity it had caused. In 1927 two men accused of the same crime in a New Jersey murder trial received different sentences because of the misuse of a semicolon. Salvatore Rannelli received a life sentence; Salvatore Merra the death sentence. In 1945, a semicolon in the definition of war crimes in the Charter of the International Military Tribunal threatened to stop the prosecution of Nazi war criminals until the ambiguities were clarified.

Use with caution is my advice.

July 4, 2021

Hailstone Of The Week

Residents in Medina County in Texas experienced what was described as a “supercell” storm on April 28th with winds gusting at speeds of between 70 and 100 miles per hour and hailstones between four and six inches in diameter. Seem like hailrocks to me.

One measuring 6.4 inches in diameter, 12 inches in circumference and weighing more than a pound fell in Hondo and has been designated as Texas’ largest ever piece of hail. The US equivalent of the Met Office, the National Weather Service, have even been able to use radar to detect its plummet to Earth, timing it at 7.35pm.

That may not have been the largest that was chucked at Texas. On social media there were pictures of a piece of hail measuring 6.57 inches in diameter that fell that night. Official verification was not possible as this manna from heaven had already been blended into a batch of margaritas.

Never look a gift horse in the mouth!

July 3, 2021

Topiary Of The Week

Trees add a bit of structure to a garden, but they can be a fruitful source of disputes between neighbours. You are entitled to cut back the branches of a tree that overhangs into your property, provided, of course, that it is not under a Preservation Order.

For 25 years or so a fir tree, now 16-feet tall, had been in Bharat Mistry’s front garden in Waterthorpe in Sheffield, although over time it had encroached over his neighbour’s property. Would you believe it, birds had the audacity to roost in it, making a noise and covering the ground with faeces.

Relations between the two households splintered and unable to find a resolution to the dispute, Bharat’s neighbour called in a tree surgeon, who successfully chopped the tree in half, removing the half that was causing offence.

The result does look a bit odd but will soon grow on you, even becoming a bit of a tourist attraction.

July 1, 2021

The Devil’s Dictionary (8)

To paraphrase Stealers Wheel, it is tempting to think that you are stuck in the middle with idiots on the left and idiots on the right. Ambrose Bierce in his The Devil’s Dictionary, first published in book form in 1912, is trenchant on the subject of the idiot. Such a person, he states, “is a member of a large and powerful tribe whose influence in human affairs has always been dominant and controlling. Then idiot’s activity is not confined to any special field of thought or action, but pervades and regulates the whole. He has the last word in everything; his decision is unappealable. He sets the opinions and fashion of taste, dictates the limitations of speech and circumscribes conduct with a dead-line”.

Or perhaps they are ignorami. Such a person is “unacquainted with certain kinds of knowledge familiar to yourself, and having certain other kinds of which you know nothing about”. Either way, it is difficult to be impartial; “unable to perceive any promise of personal advantage from espousing either side of a controversy, or adopting either of two conflicting opinions”. Those we put into those categories we might consider to be incumbents. Take care lest we fall into Bierce’s trap because an incumbent, he says, “is the person of liveliest interest to the outcumbents”.

These days we pay too much regard to income. This, he states, is “the natural and rational gauge and measure of respectability, the commonly accepted standards being artificial, arbitrary and fallacious. A common way to maximise your income is through some form of success. I once had a boss who attributed his rise up the greasy corporate ladder to the remarkable ability to never be able to make a decision. Most problems, he claimed, resolved themselves without any interference on his part. After all, indecision, as Bierce says, is “the chief element of success”.

The Draycott Murder Mystery

A review of The Draycott Murder Mystery by Molly Thynne

It was a bittersweet moment when I reached the final page of this novel. It meant that I had read all of Molly Thynne’s six murder mystery stories. My last was her first, published in 1928 and now reissued for a modern readership by Dean Street Press. Its original title, in the UK at least, was The Red Dwarf, a reference to a type of fountain pen which has a pivotal role to play in the development of the plot. I seem to be developing a thing about titles, but I prefer the original with its air of mystery to the rather prosaic American title. Either way it is a cracking read.

Given it was her first in this genre, although not her first published book, Thynne produces an impressive story, wasting no time in getting going. John Leslie returns from a walk to his farm in a storm to find the front door swinging open. Upon entering his house, he discovers a dead woman, whom he has never seen, slumped over his desk, obviously shot. With the murder weapon his own gun and having no discernible alibi – he had walked for four hours alone after having a row with his fiancée, Lady Cynthia Bell – the finger of suspicion is pointed at him. The police arrest him and the due process of the law sees him convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

Stated like that, there seems hardly enough material to make a short story, never mind a novel, even if it is hard to believe that a jury would convict and a judge would pass a capital sentence on what is little more than circumstantial evidence. There is clearly more afoot and Thynne skilfully adds layer upon layer of complexity to make a compelling story which works on two levels; will Leslie be pardoned and who really committed the murder?

As with every Golden Age detective fiction heroine in her situation, Lady Cynthia is convinced of her beau’s innocence and her friend, the invalid Sybil Kean, summons her dearest friend, Allen “Hatter” Fayre, an amateur sleuth, to dig into the case. He agrees to do so and soon discovers that the case is not so cut and dried as it appears.

The murder victim is Mrs Draycott, a woman with a penchant for rooting out dark secrets and blackmail, sister of Miss Allen who disapproves heartily of her behaviour. What has she discovered and does it hold the key to her murder? Why did she go to the farm wearing evening slippers on a stormy night and as a woman who shunned exercise why did she choose to go out on a foul night, who was she meeting and was she picked up in a car with a damaged and incomplete number plate? Why is the distinguished KC, Sybil’s husband, seemingly only going through the motions to prove Leslie’s innocence and why did he take the Red Dwarf found on the ground near the farm?

“Hatter” works through all of these conundrums and gradually pieces together the chain of events that led to Draycott’s demise. Dark secrets emerge from the past and provide the motivation for the crime. I had worked out the likely suspect but why they had committed the crime did not become clear until the end. Leaving the murder, a suicide and a natural death to one side, if you like happy endings, Thynne does not disappoint.

An impressive debut from an excellent writer in this genre. It is just a pity that she stopped after her sixth. Still, I can always reread them.

June 30, 2021

Vittoria Cottage

A review of Vittoria Cottage by D E Stevenson

Increasingly I am finding that in these times of uncertainty there is something extremely comforting about retreating into a world that is distinctly twee and cosy. It may explain why some authors, extremely popular in their day but then dismissed as old hat, are making a well-deserved comeback. One such is Scottish author, Dorothy Stevenson, who wrote forty novels over a career that spanned from 1923 to 1970 and sold over 7 million copies here and in the States.

Originally published in 1949 and now reissued by Dean Street Press, Vittoria Cottage is the first of three novels charting the fortunes of the Dering family. I always wonder about trilogies whether the author initially set out to write a three-part series or whether the trilogy just evolved. Rather like a television series that is desperate to be commissioned for a second series, Stevenson’s novel ends somewhat abruptly. I did not mind that as she had left enough clues for the reader to make their mind up as to what happened next. If I read Music In The Hills I might find out if my expectations have been fulfilled.

As with Cold Comfort Farm, there have always been Werings at Vittoria Cottage, or at least since the Regency period. The latest incumbent is Caroline, recently widowed, whose life is a struggle, juggling tight finances, keeping up appearances and trying to sort out the lives of her three children. She reminds me a little of Mrs Durrell.

Bobbie, the youngest of the brood, seems to cause no trouble, unlike Leda who is selfish and headstrong and makes an unsuitable engagement with the son of the local squire, Derek Ware. The ups and downs of the relationship do nothing to preserve the piece and calm of the household. Caroline’s son, James, is in Malaya but his return is a breath of fresh air, giving Caroline the stability and inner strength that she craves.

A handsome stranger (natch), Robert Shepperton, settles in the village and he and Caroline start to get emotionally attached. Then Caroline’s sister, the actress Harriet Fane, turns up after the run of her latest play was curtailed due to unfavourable reviews, and she makes eyes at Shepperton. Will she snatch Caroline’s just desserts from her or will she continue with her acting career and tour the States? The two sisters fall in love with the same man is a bit hackneyed, but Stevenson makes an entertaining enough and moving tale out of it.

What endeared me to Stevenson is her style. It is gentle, undemanding and easy to read but its sheer simplicity is deceiving. It is a difficult trick to pull off convincingly and just as you seem to be drifting off, she pulls you back sharply with a memorable turn of phrase or a cleverly worked joke. An example is a description of the family dog, Joss, which is described as an enigma, a breed unknown to the villagers.

Stevenson delineates her characters sufficiently enough for them to be believable, but I do not think you can claim to really know them, understand how they think. I enjoyed her portrayal of Comfort Podbury, the home help who, as her name suggests, is a little on the large side and whose ambition is to lose weight, ideally with as little effort as possible through a miracle drug.

While it not my normal fare, I enjoyed it as a form of escapism. You can understand why she was popular in her day, why she fell out of favour and why, in these desperate times, her time has come again.

June 29, 2021

Murder At Monk’s Barn

A review of Murder at Monk’s Barn by Cecil Waye

It is always a pleasure to come across a new author, although appearances can be deceptive. Cecil Waye was one of the noms de plume under which Cecil wrote, the other two being John Road and Miles Burton. Cecil Waye had four outings in a detective series featuring the Perrins, of which Murder at Monk’s Barn is the first, published originally in 1931 and now reissued by the indefatigable Dean Street Press.

This is a rather cosy, twee novel, but is an easy read, well-paced and with an ingenious method of committing a murder. Apparently, it was based on a ploy used by ANZAC troops in the trenches of the First World War. With relatively few obvious suspects it does not seem a terribly smart idea to have one of the sleuths falling head over heels in love with one of them and doing her utmost to prove their innocence.

In truth, the culprit is easy to spot, although, whilst Waye plays fair with the reader by liberally lacing his narrative with all the clues needed, the actual method by which Gilbert Wynter, shot through the head whilst shaving in his dressing room, met his end eluded me. The more I thought about the more incredible it seemed that someone in the height of emotional turmoil could have pulled it off in one go.

Waye certainly gives his readers value for money because we have not one murder but two. The second, an instance of a box of chocolates laced with poison, rather gave the game away in terms of whodunit, but he managed to obfuscate who the intended victim was with a simple but effective device.

Gilbert Wynter, a local businessman, is shot dead. The local bobby, PC Burden, hears the shot and rushes to the scene. A gun is found in the shrubbery at the spot where the fatal shot would have been discharged but the only external entrance to the garden was locked, and the victim was shot through thick curtains which were drawn at the time. Austin Wynter, fearing that the police are making a hash of the investigation, engages brother and sister detective duo, Christopher and Vivienne Perrins, to step in.

Unusually, the amateur sleuths work in tandem with the police, rather than against, and strike up a good rapport with the Inspector. Vivienne is the brains of the duo, an independent, headstrong woman, who solves the problem. Sadly, she falls in love and is destined to be married off. As it wouldn’t do for a married woman to continue working, I suspect that will be the end of her as far as the series is concerned. A shame as Christopher is a less rounded character, although he will have ample opportunity to develop. The police, though, are far more comfortable dealing with a man.

As the investigations proceed, we have the usual mix of marital infidelities, rivalry and a housemaid who has been seduced. Her plight is sympathetically handled and a garrulous postmistress and, to a lesser extent, Mrs Cunningham provide some welcome humour. The local policeman, PC Burdon, is not the stereotypical bumbling bobby and does an impressive job in garnering the evidence. The weight of evidence begins to tell against Austin Wynter.

Waye tells a good story, his style is engaging, and his characters are interesting, and, if three deaths and a nervous breakdown are discounted, with a happy ending of sorts. What more do you want?

June 28, 2021

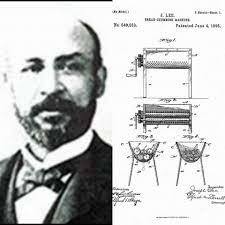

Joseph Lee And The Bread Making Machine

Bread is one of our oldest and most popular of foodstuffs, with British households buying the equivalent of twelve million loaves a day, of which just over nine million are white. There is a bewildering array of choice with over 200 different kinds of bread produced in the UK, ranging from butter-rich brioche and crisp baguettes to farmhouse loaves and focaccia, soft ciabatta and crumpets to chapattis and flaky croissants, all made possible courtesy of the vast range and quality of British flour.

The market may have been sliced up between the large bakeries (around 80% of UK bread production) and in-store bakeries (17%), but a very distinctive lockdown trend has been the increase in the number of people making their own bread at home. In the twelve weeks up to June 14, 2020 The Grocer was reporting a surge in sales of ingredients required by the home baker, flour up by 113.2%, other baking ingredients by 72.6%, baking fruits by 72.3%, and sugar by 49.7%. Such was the unanticipated demand for flour in 1.5kg bags that UK millers had to work around the clock to replenish supermarket shelves.

But, whose idea was the bread maker?

Joseph Lee was born in 1849, the son of slaves in South Carolina. After working as a servant in Beaufort, he served for eleven years in the US Coast Survey as a steward, where he developed his culinary skills. He was fascinated by the process of making bread and quickly recognised that evenly and thoroughly kneaded dough was the prerequisite for the perfect loaf.

Seeing that cooking offered him an opportunity to better himself, Lee took the bold step of opening a small local restaurant while still in his twenties. This did not satisfy his ambitions. In the 1880s he took over the Woodland Park Hotel in Newton, near Boston, a move which proved a great success, the Boston Daily Advertiser listing him as one of “Newton’s rich men” in 1886.

An extension to provide bowling alleys and billiard and pool rooms was opened to the public on May 7, 1890, completing an establishment that was “a picturesque structure with gables and towers, dormer windows, high chimneys and wide shady verandas… surrounded by seven acres of well-kept grounds”. It numbered the great and the good of Boston society amongst its clientele.

With America entering a depression in 1893, Lee had to keep a close eye on costs, focusing on a subject he knew well, bread making. Making bread by hand was laborious, delivered variable results and produced a lot of wastage. His solution was to automate the kneading process. On May 7, 1894 Lee secured a patent (No 524,042) for a kneading machine, “which will thoroughly mix and knead the dough and bring it to the desired condition without resorting to the tedious process of mixing and kneading the same by hand”.

Powered by a motor, pestles pounded the dough and screw conveyors moved it around the tray so that it was assaulted from all angles. Lee’s patent application stated that “the simplicity of construction and operation of the machine is such that it can be supplied at a minimum cost” saving time, labour and producing a superior product.

So effective was it that it did the work of six men, producing sixty pounds more bread from each barrel of flour than could be made by hand. As to quality, the Colored American magazine declared that “kneading done by it develops the gluten of the flour to an unprecedented degree, and the bread is made whiter, finer in texture, and improved in digestible qualities”.

Its efficiency meant that Lee had another problem on his hands – he was producing more bread than his guests could eat. His ingenuity knew no bounds and the following year he had devised and patented a device to mechanise the tearing, crumbling, and grinding of bread into crumbs. These were then used for everything from fried and battered fish to salad croutons and for one of America’s favourite breakfast meals before the advent of cereals, bread crumbs and milk.

Not content with the action of his kneading machine, he changed and patented the design in 1902 more closely to replicate the movement of the human hand. Eventually Lee assigned the rights to the kneading machine to The National Bread Co in return for shares and a slice of the royalties, while the bread-crumbing machine was sold to The Goodell Company of New Hampshire. He died in 1905.

By the mid-20th century automated ovens for bread making were widely used by commercial bakeries. A self-contained, all-in-one bread making machine for domestic use was a relatively recent concept, though, cooked up by the Matsushita Electric Industrial Company, now Panasonic, following research into the optimal method of kneading dough by Ikuko Tanaka. Launched in 1986, within a decade it was a must-have accessory in many an Occidental kitchen. Lee’s legacy is that all modern bread makers retain a miniaturised version of his original kneading design.

The best thing since sliced bread, you might say.