Lawrence Miles's Blog, page 8

May 21, 2011

Public Health Campaign

Published on May 21, 2011 16:56

May 17, 2011

Secs Sell 2: "The Deadly Art of Doctor Who"

After all these years, the Magnedon finally has something to tell us.

Three and a half years ago - three and a half ruddy years ago, when I still had a functioning liver, when Paul Cornell had just provided the Doctor with a love-interest who didn't come with a special patch in case she got a puncture, and when Life on Mars had given the BBC a time-travel double-whammy which briefly convinced someone, somewhere, that John Simm would make a better Master than Derek Jacobi - I wrote an article called "Secs Sells". It was, for the most part, about toys.

If you recall, this sort of thing made sense in 2007. It was the year when Doctor Who seemed to swallow the world of consumer plastics like a great big Sumo Auton, when every sensible child's Christmas list proved that we had definitely won. Dalek Sec masks were being advertised on TV. You know, properly advertised. In the ad-breaks. Not just in black-and-white photocopied catalogues that made the action figures look like highly specialised marital aids, the way Dapol models used to be.

And yet... even then, even in the Winter of the Voice-Changer, there was something happening in Tesco's toy department that made us wonder if this wasn't still Dapol's World. The Character range was going pleasantly berserk, producing things that not even the world's least rational foetus would seriously play with rather than just collect. The Faceless Old Woman toy was my personal favourite, although the Burst Cassandra has since become legendary in its absolute uselessness, unless you're thinking of setting it on fire and making K-9 jump through it. Let's be honest, in a series which so routinely turns conventional items into potential threats, even monsters that work conceptually - which is to say, monsters that make perfect sense if you've seen the episode - become bizarre when moulded in plastic. A Weeping Angel figurine, out of context, is a very poor garden ornament. A little boy in a gas-mask would've seemed a perverse sort of plaything to our grandparents. A poseable Auton would've been pushing it even in Pertwee's day.

There were other oddities, like the 9" David Tennant in "Impossible Planet" space-gear, such a lost-looking throwback to Action Man's space-exploration phase that you had to wonder why he didn't have a voice-recorder in his backpack. Of the kind, O my Best Beloved, that you must particularly never take into the bath. Even though you may feel morally obliged to do so when there's a water-planet to explore. Remember, though, how New-School Doctor Who was itself undergoing a rather stressful adolescence at this point. I still maintain that "The Sound of Drums" was the point at which the programme Formally Jumped the Shark, not because it was singularly awful (we'd already had much worse), but because it was the point at which Russell T. Davies started writing scripts for the BAFTA audience rather than the general public. We ended up with an episode, and ultimately a series, in which television itself was the only reality.

So I said, at the time, that the best way of monitoring the series' impact on the Cultural Mass was to watch what happened to the toys. This seems like a good moment to come back to that idea. And not, as you may think, because we're now due for an action figure of Matt Smith in a f***ing Stetson. Instead, I'd like to go off a tangent that explores another way in which Doctor Who has traditionally interacted with the real world... especially at Play Time.

But to do that, I'm going to have to remind you all of Totally Doctor Who.

Now, I'm not a great supporter of (or, since around 2008, even a viewer of) Doctor Who Confidential. It made sense when the Great Journey of Life began again in 2005, but there's only so much to say behind-the-scenes before it becomes a celebration of... the idea that Doctor Who needs to be celebrated. Like DVDs that give you two hours of special features for every hour of movie, it's a work of fetishism above all else. Totally Doctor Who, now, that was remarkable. Simply by existing, perhaps even more unlikely than the victory of the Dalek Sec masks. Sorry? No, well, you weren't the target audience. Not even with someone as eminently capable as Kirsten "Yoghurt-Pants" O'Brien in front of the camera. It had to end, though, as soon as Catherine Tate became a regular fixture. If the emotional hook of a series involves someone who talks about temp work all the time, then no side-show is ever going to appeal to a schoolgoing audience. Nonetheless, the fact that Totally ran for two seasons has to be considered something of a triumph.

This is interesting, when you consider what's happening on CBBC in 2011. I may have to do some explaining here, because I sense that you're not as familiar with it as I might be, nor capable of joining in with most of the songs from Horrible Histories (incidentally, if you want to study the way anachronism has become the collage form of the twenty-first century, then this is at least as important as Doctor Who... plus, Viking rock ballad). Here I'm thinking particularly of Deadly 60. No? Very well. This is essentially the Extreme Sports version of natural history, in which Steve Backshall - mildly irritating at first, until you realise that he's genuinely excited about getting bitten by giant ants - goes in search of the sixty deadliest life-forms on the planet. Even as a method of presenting wildlife to children (ohhh yes, especially boys), this might be unbearable, if it weren't for the fact that Backshall doesn't do things by halves. We're exposed to hideous parasites and hugely unlikely species of squid-thing, not simply the Big Name Predators, and most of them make at least a token effort to savage the presenter. That said, the Big Name Predator footage is something special: David Attenborough's cameraman never came within two feet of getting his arms ripped off by a tiger, and it's genuinely terrifying to watch.

But Deadly 60 has its own pilot-fish programme, Deadly Art. This is the latest and most carnivorous offshoot of the Take Hart format (or Art Attack, if you're dead common), and you can probably see how it all fits together. We get a precis of the accompaying Deadly 60, and then two artists in the studio - usually young women, y'know, like with Tony Hart - make A GIGANTIC SODDING PRAYING MANTIS WITH GLOWING EYES OUT OF SCRAP METAL. Only pausing to run off a smaller version out of the sort of thing you might find, ooh, in your bins.

By now, you should be thinking: Wait a minute. Deadly 60 gets that as a spin-off, and we only get Doctor Who Confidential...? If you aren't, then you have no soul and I pity you, but I'll continue anyway.

The problem is, this comes closer to the nature of the way Doctor Who has traditionally functioned (and here "traditionally" goes at least up until 2007, possibly further) than any spin-off the programme has actually managed to create. Doctor Who was always a tactile thing, even when it came as close as the budget would allow to high-concept. Experiment is in its nature, and that rubs off on you. Yes, we did use wasteground to simulate quarries, either the kind which themselves simulated other planets or the kind where one might reasonably be expected to find a fossilised alien hand. I know for a fact, and from personal observation which under certain other circumstances might lead to a restraining order, that children in the Tennant era used cardboard boxes to reconstruct both monsters and architectures from the modern episodes ("YOU CAN'T TOUCH ME, I'M INSIDE THE TARDIS!"). Even the "Blink" game only works properly if you can play it in the presence of actual, definite statues.

Let me clarify this: if we imagine a theoretical Doctor Who Art, then we're not considering insipid "makes" a la Blue Peter. That would put Character out of business, and besides, you can probably tell from the awful bonus feature on "Talons of Weng-Chiang" that teeny-tiny reconstructions of Doctor Who stories were never popular even in the '70s (while the part about using your sister's violin-oil makes even me feel working-class). What's notable about Deadly 60's spin-off is how the materials of Termite Art, art made from accumulated bits and pieces, fit the subject matter so precisely. It'd be glib to suggest that Termite Art is good for making termites, but you can easily see how household detritus would resemble claws, scales, and pirranha-teeth rather than anything in classical sculpture.

As it was, so it should also be. Doctor Who has always been a creature of Found Parts, for reasons far beyond the BBC's make-do-and-mend requirements. We can trace this all the way back to 1963. The Magnedon, sharp-edged and slack-jawed in its petrified jungle, is a Hell of a lot like the kind of thing the Deadly Artists produce on a weekly basis. The idea of a Magnedon being a backyard project is... more than tempting, from an eight-year-old's perspective. "The Keys of Marinus" is even more obviously made of left-overs, and yes, I would like to build myself a statue that I can put my own arms through. Fine, we can keep "The Sensorites" for the inevitable model spaceship episode (yawn). But "The Aztecs"? "The Aztecs"...! I'm thinking, Barbara's headpiece. Maybe even an Aztec sacrificial mask. Okay, anyone who doesn't think that making an Aztec sacrificial mask would be cooler than an action figure of Matt Smith in a Stetson can now officially naff off and go back to watching Stargate.

The reason I'm examining this purely theoretical hybrid spin-off is really quite simple. I've argued that something along these lines is in Doctor Who's most primal nature, on-screen and off: for a programme that thrives on the palpable, that does wonders with men in big chunky monster costumes and goes belly-up when it tries to look like a CGI horror movie, this sense of stuff chimes with everything from the Very First Monster We Ever See to the Radio Times ad from 2006. (You may recall that when the RT first advertised on ITV, it began in the week of the "Rise of the Cybermen" cover. It involved a small boy making himself Cyber-armour out of tinfoil. See, I told you it wasn't entirely a twentieth-century thing.) But...? Yes, you knew there'd be a but. But at a time when a programme of this kind actually exists in a BBC children's slot, weirdly related to the real world rather than a haunted forest on a planet full of Daleks, Doctor Who itself... couldn't do it.

This lack of getting-your-hands-dirty-ness tells us a lot about what's changed, even more than we might have expected the toys to. It felt perfectly natural for the 2006 series to segue into something as DIY as Totally, and it would've felt almost as natural for it to link into a session of Termite Art (not in the case of every episode, although some awareness of the child-viewer's urge to create might have caused more people working on "Fear Her" to do their jobs properly). For the Smith Era... not so natural. Given Moffat's technique of making Doctor Who as much like a surrogate action-movie as budget allows, "Day of the Moon" was never going to resemble anything you can make out of packing material. "Curse of the Black Spot" is more likely to have an impact on the real world, if only in terms of shouting "arrr!", yet its strangeness comes from a lighting effect imposed on a supermodel. Rather annoyingly, "The Doctor's Wife" gives us a whole junkyard world - no, better than that, a TARDIS junkyard world - but then uses it as background. Even the moment of actual salvage is a plot convenience rather than a celebration of Found Parts.

Here we'll assume that playing in a skip is, at least symbolically, a good thing. (Symbolically, it's what virtually every pioneer in both the cinematic arts and radiophonics did, so this is a safe assertion as long as you've got some iodine handy in case of scrapes.) On any level, this isn't the sort of thing Doctor Who encourages in the current phase. There are many niggling reasons for that, but it comes down to one key point: Doctor Who is now a brand. It says so on the back of the Michael Moorcock novel, in big letters, so it must be true. "One of the biggest brands in sci-fi," no less. But then, it's not as if we weren't forewarned. First we got the company logo, then we got the range of excitingly-coloured Daleks.

This isn't the first time it's been pitched this way. Just a Russell T. Davies became so bound up in his role as Toast of the Showbiz World that he started making a programme explicitly for people who work in TV, John Nathan-Turner became so bound up in his role as Toast of Fandom (this was in his early period, you understand, before fanzines started announcing fatwahs) that his version of programme-making became divorced from anything outside Doctor Who itself. He'd spend more and more time at conventions, where people would hang on his every word, and cheer whenever he'd say anything like "well, of course, the Ice Warriors might be back next year". The ultimate result, beyond "Attack of the Cybermen" and stories which treated the Rani meeting the Autons as a major selling-point, was to turn the Series Concept into something which largely existed to be sold and oversold to those who already believed in it. Personally, I can forgive the merchandising. The Doctor Who Cookbook at least wanted us to know it was ridiculous, or they wouldn't have put a Yeti in an apron on the cover; and despite Tat Wood's insistence, I've yet to see definite proof that Knit a TARDIS ever existed. No, the issue wasn't the bumf, it was the crippling sense of self-involvement.

Yet Doctor Who in the '80s at least retained one advantage: it was genuinely unique. Season Eighteen may have been in competition with Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, but nobody ever really thought they were meant to have anything in common. And when ITV finally won its great victory circa 1985, with a version of Robin Hood that was demonstrably better (certainly more of-its-time) than "Timelash", you could at least truthfully say they weren't on the same turf. Now, though, Doctor Who isn't the only game in town. It does high-visibility, high-maintenance fantasy... and so does everybody else, from Hollywood downwards, if that's an accurate use of "downwards". The reason the series has to be branded is that it can't retain an identity any other way. We can see a difference, mainly because we're the kind of gits who remember the past too well, but the general audience no longer perceives a gulf between this and the Next Effects Series Along. Many excuses have been made for the relatively feeble viewing figures in 2011, although the most important point has been politely coughed over. The last series of Merlin got higher viewing figures while being threatened by X Factor than this does against pretty-much-nothing-at-all.

As in the '80s, the shift towards branding Doctor Who means appealing to the existing fan-base, if in a slightly different way. Whereas Nathan-Turner tried to do it by overloading episodes with Old Favourites...

(...sorry, I'd honestly forgotten "The Pandorica Opens" until that moment, and it took me a few moments to stop chuckling...)

...we note that all the factors used to keep the series solvent in the 20-teens are favourites of the modern sci-fi fan. You know the ones I mean, you can count 'em off yourselves. Ratings are always a treacherous guide, but is anyone really surprised that viewing figures went back up for "Curse of the Black Spot"? Doctor Who vs Pirates vs Mermaids isn't terribly original, yet at least it puts the programme in a different space from anything else on TV (well, until the Johnny Depp movie a few days later). An Angel-age storyline about a time-baby pregnancy, or snatches of future events that aren't designed to be comprehensible even to the dedicated viewer, are of no interest to anyone except - ironically, given recent controversies - the kind of people who care about spoilers. If the Termite Art version of television provokes the viewer into going outside and poking around to see what's there (and I still hold that this is what most good telly does, especially children's telly), then this is more like siege conditions. Branding always closes the gates. This is your product, you don't need anything else.

Which brings us back to that other sort of product, the "real" toys and games that don't seem real at all. I was right about this, at the very least: you can tell the programme's status from whatever's in the shops. What we have in May 2011, heavily-pitched on commercial TV (and tellingly, often late at night), is the trading-card game that promises "awesome alien beatdowns". Wholly insular, and almost unplayable as a game unless you're already hooked on Yu-Gi-Oh - yes, of course I know about this sort of thing - it exists to flog trading-cards to boys who've already been sold on the idea of buying trading-cards. While we could at least laugh at Tom Baker underpants, and while Dalek Sec seemed like a triumph even though we didn't necessarily like "Evolution of the Daleks" very much, this is... all right. Let's call it a different sort of phenomenon, and leave it at that.

You can't even make a shark out of it.

Three and a half years ago - three and a half ruddy years ago, when I still had a functioning liver, when Paul Cornell had just provided the Doctor with a love-interest who didn't come with a special patch in case she got a puncture, and when Life on Mars had given the BBC a time-travel double-whammy which briefly convinced someone, somewhere, that John Simm would make a better Master than Derek Jacobi - I wrote an article called "Secs Sells". It was, for the most part, about toys.

If you recall, this sort of thing made sense in 2007. It was the year when Doctor Who seemed to swallow the world of consumer plastics like a great big Sumo Auton, when every sensible child's Christmas list proved that we had definitely won. Dalek Sec masks were being advertised on TV. You know, properly advertised. In the ad-breaks. Not just in black-and-white photocopied catalogues that made the action figures look like highly specialised marital aids, the way Dapol models used to be.

And yet... even then, even in the Winter of the Voice-Changer, there was something happening in Tesco's toy department that made us wonder if this wasn't still Dapol's World. The Character range was going pleasantly berserk, producing things that not even the world's least rational foetus would seriously play with rather than just collect. The Faceless Old Woman toy was my personal favourite, although the Burst Cassandra has since become legendary in its absolute uselessness, unless you're thinking of setting it on fire and making K-9 jump through it. Let's be honest, in a series which so routinely turns conventional items into potential threats, even monsters that work conceptually - which is to say, monsters that make perfect sense if you've seen the episode - become bizarre when moulded in plastic. A Weeping Angel figurine, out of context, is a very poor garden ornament. A little boy in a gas-mask would've seemed a perverse sort of plaything to our grandparents. A poseable Auton would've been pushing it even in Pertwee's day.

There were other oddities, like the 9" David Tennant in "Impossible Planet" space-gear, such a lost-looking throwback to Action Man's space-exploration phase that you had to wonder why he didn't have a voice-recorder in his backpack. Of the kind, O my Best Beloved, that you must particularly never take into the bath. Even though you may feel morally obliged to do so when there's a water-planet to explore. Remember, though, how New-School Doctor Who was itself undergoing a rather stressful adolescence at this point. I still maintain that "The Sound of Drums" was the point at which the programme Formally Jumped the Shark, not because it was singularly awful (we'd already had much worse), but because it was the point at which Russell T. Davies started writing scripts for the BAFTA audience rather than the general public. We ended up with an episode, and ultimately a series, in which television itself was the only reality.

So I said, at the time, that the best way of monitoring the series' impact on the Cultural Mass was to watch what happened to the toys. This seems like a good moment to come back to that idea. And not, as you may think, because we're now due for an action figure of Matt Smith in a f***ing Stetson. Instead, I'd like to go off a tangent that explores another way in which Doctor Who has traditionally interacted with the real world... especially at Play Time.

But to do that, I'm going to have to remind you all of Totally Doctor Who.

Now, I'm not a great supporter of (or, since around 2008, even a viewer of) Doctor Who Confidential. It made sense when the Great Journey of Life began again in 2005, but there's only so much to say behind-the-scenes before it becomes a celebration of... the idea that Doctor Who needs to be celebrated. Like DVDs that give you two hours of special features for every hour of movie, it's a work of fetishism above all else. Totally Doctor Who, now, that was remarkable. Simply by existing, perhaps even more unlikely than the victory of the Dalek Sec masks. Sorry? No, well, you weren't the target audience. Not even with someone as eminently capable as Kirsten "Yoghurt-Pants" O'Brien in front of the camera. It had to end, though, as soon as Catherine Tate became a regular fixture. If the emotional hook of a series involves someone who talks about temp work all the time, then no side-show is ever going to appeal to a schoolgoing audience. Nonetheless, the fact that Totally ran for two seasons has to be considered something of a triumph.

This is interesting, when you consider what's happening on CBBC in 2011. I may have to do some explaining here, because I sense that you're not as familiar with it as I might be, nor capable of joining in with most of the songs from Horrible Histories (incidentally, if you want to study the way anachronism has become the collage form of the twenty-first century, then this is at least as important as Doctor Who... plus, Viking rock ballad). Here I'm thinking particularly of Deadly 60. No? Very well. This is essentially the Extreme Sports version of natural history, in which Steve Backshall - mildly irritating at first, until you realise that he's genuinely excited about getting bitten by giant ants - goes in search of the sixty deadliest life-forms on the planet. Even as a method of presenting wildlife to children (ohhh yes, especially boys), this might be unbearable, if it weren't for the fact that Backshall doesn't do things by halves. We're exposed to hideous parasites and hugely unlikely species of squid-thing, not simply the Big Name Predators, and most of them make at least a token effort to savage the presenter. That said, the Big Name Predator footage is something special: David Attenborough's cameraman never came within two feet of getting his arms ripped off by a tiger, and it's genuinely terrifying to watch.

But Deadly 60 has its own pilot-fish programme, Deadly Art. This is the latest and most carnivorous offshoot of the Take Hart format (or Art Attack, if you're dead common), and you can probably see how it all fits together. We get a precis of the accompaying Deadly 60, and then two artists in the studio - usually young women, y'know, like with Tony Hart - make A GIGANTIC SODDING PRAYING MANTIS WITH GLOWING EYES OUT OF SCRAP METAL. Only pausing to run off a smaller version out of the sort of thing you might find, ooh, in your bins.

By now, you should be thinking: Wait a minute. Deadly 60 gets that as a spin-off, and we only get Doctor Who Confidential...? If you aren't, then you have no soul and I pity you, but I'll continue anyway.

The problem is, this comes closer to the nature of the way Doctor Who has traditionally functioned (and here "traditionally" goes at least up until 2007, possibly further) than any spin-off the programme has actually managed to create. Doctor Who was always a tactile thing, even when it came as close as the budget would allow to high-concept. Experiment is in its nature, and that rubs off on you. Yes, we did use wasteground to simulate quarries, either the kind which themselves simulated other planets or the kind where one might reasonably be expected to find a fossilised alien hand. I know for a fact, and from personal observation which under certain other circumstances might lead to a restraining order, that children in the Tennant era used cardboard boxes to reconstruct both monsters and architectures from the modern episodes ("YOU CAN'T TOUCH ME, I'M INSIDE THE TARDIS!"). Even the "Blink" game only works properly if you can play it in the presence of actual, definite statues.

Let me clarify this: if we imagine a theoretical Doctor Who Art, then we're not considering insipid "makes" a la Blue Peter. That would put Character out of business, and besides, you can probably tell from the awful bonus feature on "Talons of Weng-Chiang" that teeny-tiny reconstructions of Doctor Who stories were never popular even in the '70s (while the part about using your sister's violin-oil makes even me feel working-class). What's notable about Deadly 60's spin-off is how the materials of Termite Art, art made from accumulated bits and pieces, fit the subject matter so precisely. It'd be glib to suggest that Termite Art is good for making termites, but you can easily see how household detritus would resemble claws, scales, and pirranha-teeth rather than anything in classical sculpture.

As it was, so it should also be. Doctor Who has always been a creature of Found Parts, for reasons far beyond the BBC's make-do-and-mend requirements. We can trace this all the way back to 1963. The Magnedon, sharp-edged and slack-jawed in its petrified jungle, is a Hell of a lot like the kind of thing the Deadly Artists produce on a weekly basis. The idea of a Magnedon being a backyard project is... more than tempting, from an eight-year-old's perspective. "The Keys of Marinus" is even more obviously made of left-overs, and yes, I would like to build myself a statue that I can put my own arms through. Fine, we can keep "The Sensorites" for the inevitable model spaceship episode (yawn). But "The Aztecs"? "The Aztecs"...! I'm thinking, Barbara's headpiece. Maybe even an Aztec sacrificial mask. Okay, anyone who doesn't think that making an Aztec sacrificial mask would be cooler than an action figure of Matt Smith in a Stetson can now officially naff off and go back to watching Stargate.

The reason I'm examining this purely theoretical hybrid spin-off is really quite simple. I've argued that something along these lines is in Doctor Who's most primal nature, on-screen and off: for a programme that thrives on the palpable, that does wonders with men in big chunky monster costumes and goes belly-up when it tries to look like a CGI horror movie, this sense of stuff chimes with everything from the Very First Monster We Ever See to the Radio Times ad from 2006. (You may recall that when the RT first advertised on ITV, it began in the week of the "Rise of the Cybermen" cover. It involved a small boy making himself Cyber-armour out of tinfoil. See, I told you it wasn't entirely a twentieth-century thing.) But...? Yes, you knew there'd be a but. But at a time when a programme of this kind actually exists in a BBC children's slot, weirdly related to the real world rather than a haunted forest on a planet full of Daleks, Doctor Who itself... couldn't do it.

This lack of getting-your-hands-dirty-ness tells us a lot about what's changed, even more than we might have expected the toys to. It felt perfectly natural for the 2006 series to segue into something as DIY as Totally, and it would've felt almost as natural for it to link into a session of Termite Art (not in the case of every episode, although some awareness of the child-viewer's urge to create might have caused more people working on "Fear Her" to do their jobs properly). For the Smith Era... not so natural. Given Moffat's technique of making Doctor Who as much like a surrogate action-movie as budget allows, "Day of the Moon" was never going to resemble anything you can make out of packing material. "Curse of the Black Spot" is more likely to have an impact on the real world, if only in terms of shouting "arrr!", yet its strangeness comes from a lighting effect imposed on a supermodel. Rather annoyingly, "The Doctor's Wife" gives us a whole junkyard world - no, better than that, a TARDIS junkyard world - but then uses it as background. Even the moment of actual salvage is a plot convenience rather than a celebration of Found Parts.

Here we'll assume that playing in a skip is, at least symbolically, a good thing. (Symbolically, it's what virtually every pioneer in both the cinematic arts and radiophonics did, so this is a safe assertion as long as you've got some iodine handy in case of scrapes.) On any level, this isn't the sort of thing Doctor Who encourages in the current phase. There are many niggling reasons for that, but it comes down to one key point: Doctor Who is now a brand. It says so on the back of the Michael Moorcock novel, in big letters, so it must be true. "One of the biggest brands in sci-fi," no less. But then, it's not as if we weren't forewarned. First we got the company logo, then we got the range of excitingly-coloured Daleks.

This isn't the first time it's been pitched this way. Just a Russell T. Davies became so bound up in his role as Toast of the Showbiz World that he started making a programme explicitly for people who work in TV, John Nathan-Turner became so bound up in his role as Toast of Fandom (this was in his early period, you understand, before fanzines started announcing fatwahs) that his version of programme-making became divorced from anything outside Doctor Who itself. He'd spend more and more time at conventions, where people would hang on his every word, and cheer whenever he'd say anything like "well, of course, the Ice Warriors might be back next year". The ultimate result, beyond "Attack of the Cybermen" and stories which treated the Rani meeting the Autons as a major selling-point, was to turn the Series Concept into something which largely existed to be sold and oversold to those who already believed in it. Personally, I can forgive the merchandising. The Doctor Who Cookbook at least wanted us to know it was ridiculous, or they wouldn't have put a Yeti in an apron on the cover; and despite Tat Wood's insistence, I've yet to see definite proof that Knit a TARDIS ever existed. No, the issue wasn't the bumf, it was the crippling sense of self-involvement.

Yet Doctor Who in the '80s at least retained one advantage: it was genuinely unique. Season Eighteen may have been in competition with Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, but nobody ever really thought they were meant to have anything in common. And when ITV finally won its great victory circa 1985, with a version of Robin Hood that was demonstrably better (certainly more of-its-time) than "Timelash", you could at least truthfully say they weren't on the same turf. Now, though, Doctor Who isn't the only game in town. It does high-visibility, high-maintenance fantasy... and so does everybody else, from Hollywood downwards, if that's an accurate use of "downwards". The reason the series has to be branded is that it can't retain an identity any other way. We can see a difference, mainly because we're the kind of gits who remember the past too well, but the general audience no longer perceives a gulf between this and the Next Effects Series Along. Many excuses have been made for the relatively feeble viewing figures in 2011, although the most important point has been politely coughed over. The last series of Merlin got higher viewing figures while being threatened by X Factor than this does against pretty-much-nothing-at-all.

As in the '80s, the shift towards branding Doctor Who means appealing to the existing fan-base, if in a slightly different way. Whereas Nathan-Turner tried to do it by overloading episodes with Old Favourites...

(...sorry, I'd honestly forgotten "The Pandorica Opens" until that moment, and it took me a few moments to stop chuckling...)

...we note that all the factors used to keep the series solvent in the 20-teens are favourites of the modern sci-fi fan. You know the ones I mean, you can count 'em off yourselves. Ratings are always a treacherous guide, but is anyone really surprised that viewing figures went back up for "Curse of the Black Spot"? Doctor Who vs Pirates vs Mermaids isn't terribly original, yet at least it puts the programme in a different space from anything else on TV (well, until the Johnny Depp movie a few days later). An Angel-age storyline about a time-baby pregnancy, or snatches of future events that aren't designed to be comprehensible even to the dedicated viewer, are of no interest to anyone except - ironically, given recent controversies - the kind of people who care about spoilers. If the Termite Art version of television provokes the viewer into going outside and poking around to see what's there (and I still hold that this is what most good telly does, especially children's telly), then this is more like siege conditions. Branding always closes the gates. This is your product, you don't need anything else.

Which brings us back to that other sort of product, the "real" toys and games that don't seem real at all. I was right about this, at the very least: you can tell the programme's status from whatever's in the shops. What we have in May 2011, heavily-pitched on commercial TV (and tellingly, often late at night), is the trading-card game that promises "awesome alien beatdowns". Wholly insular, and almost unplayable as a game unless you're already hooked on Yu-Gi-Oh - yes, of course I know about this sort of thing - it exists to flog trading-cards to boys who've already been sold on the idea of buying trading-cards. While we could at least laugh at Tom Baker underpants, and while Dalek Sec seemed like a triumph even though we didn't necessarily like "Evolution of the Daleks" very much, this is... all right. Let's call it a different sort of phenomenon, and leave it at that.

You can't even make a shark out of it.

Published on May 17, 2011 20:53

May 15, 2011

Oh, All Right

Re: the thing that's even worse than the Doctor running around with a ray-gun.

To be honest, it's not atypical for Neil Gaiman to take something innately complex and shape it into something incredibly crass and attention-grabbing: if you can turn Death into a goth pin-up, then the TARDIS isn't going to stand a chance. The obvious thing to say at this point is that in a phase of the series where the only impressive thing the Doctor can do is flirt, and where every scene has the emotional depth and maturity of Han Solo saying "I know" before being pushed into the carbonite, the TARDIS was inevitably going to become the latest in a line of inflatable dolls posing as female characters. But the more important point is that everyone who's reading this probably will, and definitely should, know someone more interesting. The banality of the TARDIS-as-person is part of the design, of course, because it makes us feel that - hey! - we ourselves aren't that much smarter, wiser, or well-travelled. Gaiman's mind-trap, like Moffat's, is that nothing should appear to be cooler than the viewer... except the writer.

It's an obvious irony that this comes in the same week as BBC4's repeat of "Hand of Fear", in which a TARDIS without legs has more personality than the version with a face. No, worse still: even Bob Baker and Dave Martin, reviled by many as the hacks of the '70s, gave the supporting characters a life outside the frame. If Doctor Who still pitched itself as drama, rather than a checklist of egregious fan-wank, then you'd care about Uncle and Aunty more than anything else in the episode. We're not supposed to care, because LOOK, THE TARDIS IS A WOMAN!!!

But I don't recognise that as the TARDIS, any more than I recognise this Buck-Rogers-in-a-Bow-Tie version of the Doctor as the character I used to believe in. The TARDIS is meant to be better than this. So is her pilot. So is the programme.

To be honest, it's not atypical for Neil Gaiman to take something innately complex and shape it into something incredibly crass and attention-grabbing: if you can turn Death into a goth pin-up, then the TARDIS isn't going to stand a chance. The obvious thing to say at this point is that in a phase of the series where the only impressive thing the Doctor can do is flirt, and where every scene has the emotional depth and maturity of Han Solo saying "I know" before being pushed into the carbonite, the TARDIS was inevitably going to become the latest in a line of inflatable dolls posing as female characters. But the more important point is that everyone who's reading this probably will, and definitely should, know someone more interesting. The banality of the TARDIS-as-person is part of the design, of course, because it makes us feel that - hey! - we ourselves aren't that much smarter, wiser, or well-travelled. Gaiman's mind-trap, like Moffat's, is that nothing should appear to be cooler than the viewer... except the writer.

It's an obvious irony that this comes in the same week as BBC4's repeat of "Hand of Fear", in which a TARDIS without legs has more personality than the version with a face. No, worse still: even Bob Baker and Dave Martin, reviled by many as the hacks of the '70s, gave the supporting characters a life outside the frame. If Doctor Who still pitched itself as drama, rather than a checklist of egregious fan-wank, then you'd care about Uncle and Aunty more than anything else in the episode. We're not supposed to care, because LOOK, THE TARDIS IS A WOMAN!!!

But I don't recognise that as the TARDIS, any more than I recognise this Buck-Rogers-in-a-Bow-Tie version of the Doctor as the character I used to believe in. The TARDIS is meant to be better than this. So is her pilot. So is the programme.

Published on May 15, 2011 14:42

May 11, 2011

Thirty Books from Interrupted Worlds

Inspired by Philip Purser-Hallard's @trapphic Twitter-stream (a series of 140-character micro-stories, entirely original in his case). The following are all classic works of literature by well-remembered authors, abridged to exactly 140 characters for easy dissemination among the puny humans, but taken from those universes where events have been influenced by multiple timelines, anachronistic technologies, or Things That Should Not Be.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times; it was an age of wisdom, it was an age of Roman legionnaires riding about on dinosaurs.

- Charles Dickens

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a time machine must be in need of a wife who's really his own nan.

- Jane Austen

It was only when she saw the tendril attached to the rabbit's back that Alice realised how the Xithraxi went "fishing" for psychic children.

- Lewis Carroll

After driving out the animals, the MetaTermites wrote on the side of the barn: FOUR LEGS GOOD. SIX LEGS BEST. Then the UltraSpiders arrived.

- George Orwell

"It is not only the Heights that seem so curiously disposed," Heathcliff warned, "but the Widths, Lengths, and... perhaps other dimensions."

- Emily Brontë

Disguised as a washer-woman, Mr Toad found it easy to slip past the jailer. The bizarre inconsistency in scale had destroyed the man's mind.

- Kenneth Grahame

"You mean I can't get out of this unless I kill my own grandfather, but if I kill my own grandfather, I won't be around to get out of this?"

- Joseph Heller

24 hours later, Fogg returned with Hitler's crown and the Grail of Saladin. His friends claimed he'd definitely said *one* world, 80 *days*.

- Jules Verne

It was chaos: when the boys on the island learned they were being killed by public vote, they tore off Davina's head and stuck it on a pole.

- William Golding

Now Mary understood the secret of Jamaica Inn. Its eerie mystique was a beacon, allowing the locals to kill and rob any curious Time Agents.

- Daphne du Maurier

"Why, you're a Son of Adam!" said Mr Beaver, delighted. "Our race has been interbreeding with yours for millennia. How are our death-spawn?"

- C. S. Lewis

On winter evenings, Beth would sit by the fire and sew Higgs-Bosons onto subatomic quilts, while Amy would carp about modern-day relativism.

- Louisa May Alcott

"Lolita, fire of my loins, light of my life. And apparently it isn't legal even if you use a tachyonic accelerator to make them look older."

- Vladimir Nabokov

"Oh bother!" said Pooh. "It's bad enough that my back half is stuck in Rabbit's kitchen, but my front half is in the universe of Nazi bees."

- A. A. Milne

"The warpship wreck had inverted space and time, marooning me on a single day, far from the present. Still, at least I had my Man Sideways."

- Daniel Defoe

I'M TRANSMITTING THIS FROM YOUR FUTURE. STOP RIGHT NOW, ALL RIGHT? YOU DON'T WANT TO CARRY ON WITH THIS. TRUST ME, IT'S REALLY NOT WORTH IT.

- Salman Rushdie

"Its back shines like quicksilver," said Ahab, "and in its gut, Hell's own wrath. Aye, a uranium coin for the first to spy the Red October!"

- Herman Melville

riverrun, in stream of conscientiousness, wilfitfully scarding sense to halve the Horror from 'Cross Eternity and its rrravaging of rrreason

- James Joyce

Once she'd dug a well for the villagers, adding her own DNA drones to the water was simple. Oh yes: this town would be *exactly* like Alice.

- Nevil Shute

D'Artagnon's faith in "one for all, and all for one" was only tested when he felt the Musketeer Gestalt surreptitiously borrowing his liver.

- Alexander Dumas

"Yet on some whim, I Judas' nipple brushed / That cold tomb swung aside, and there revealed / A lower level still, that's like the Batcave."

- Dante

"You fool," growled his anti-world counterpart, as its claws tore through his duffelcoat. "Did you really think yours was the Darkest Peru?"

- Michael Bond

"Nanocure Kurtz-G318 has gone native inside the Congolese ambassador. We think it's arranged the cancer cells into its own personal empire."

- Joseph Conrad

Among those at the Paris barricade was Les Miserables, a '70s club comic who'd become unstuck in time. France remembered him subconsciously.

- Victor Hugo

The golden age ended in 1963, when a study found that not every tank-engine required AI to be efficient, especially on island branch-lines.

- The Reverend W. Awdry

Mina accepted her fate after realising that Dracula means "Son of the Dragon", and that he could give her rides "like in Neverending Story".

- Bram Stoker

"Reader: I married him. This was considered daringly metatextual, yet it was a preferable narrative device to the Fourth-Wall Siege Engine."

- Charlotte Brontë

Its four arms became helicopter blades; its turret, a great cannon. But Rotatron, leader of the Windmillcons, was about to meet its nemesis.

- Cervantes

El-Ahrairah gazed beyond the portal, at all the worlds his people would infest. From this day, he'd be the Prince with Nine-Billion Enemies.

- Richard Adams

"Long before becoming Emperor, I visited the Sybil at Cunae. She revealed to me a monstrous prophecy about a place called the Night Garden."

- Robert Graves

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times; it was an age of wisdom, it was an age of Roman legionnaires riding about on dinosaurs.

- Charles Dickens

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a time machine must be in need of a wife who's really his own nan.

- Jane Austen

It was only when she saw the tendril attached to the rabbit's back that Alice realised how the Xithraxi went "fishing" for psychic children.

- Lewis Carroll

After driving out the animals, the MetaTermites wrote on the side of the barn: FOUR LEGS GOOD. SIX LEGS BEST. Then the UltraSpiders arrived.

- George Orwell

"It is not only the Heights that seem so curiously disposed," Heathcliff warned, "but the Widths, Lengths, and... perhaps other dimensions."

- Emily Brontë

Disguised as a washer-woman, Mr Toad found it easy to slip past the jailer. The bizarre inconsistency in scale had destroyed the man's mind.

- Kenneth Grahame

"You mean I can't get out of this unless I kill my own grandfather, but if I kill my own grandfather, I won't be around to get out of this?"

- Joseph Heller

24 hours later, Fogg returned with Hitler's crown and the Grail of Saladin. His friends claimed he'd definitely said *one* world, 80 *days*.

- Jules Verne

It was chaos: when the boys on the island learned they were being killed by public vote, they tore off Davina's head and stuck it on a pole.

- William Golding

Now Mary understood the secret of Jamaica Inn. Its eerie mystique was a beacon, allowing the locals to kill and rob any curious Time Agents.

- Daphne du Maurier

"Why, you're a Son of Adam!" said Mr Beaver, delighted. "Our race has been interbreeding with yours for millennia. How are our death-spawn?"

- C. S. Lewis

On winter evenings, Beth would sit by the fire and sew Higgs-Bosons onto subatomic quilts, while Amy would carp about modern-day relativism.

- Louisa May Alcott

"Lolita, fire of my loins, light of my life. And apparently it isn't legal even if you use a tachyonic accelerator to make them look older."

- Vladimir Nabokov

"Oh bother!" said Pooh. "It's bad enough that my back half is stuck in Rabbit's kitchen, but my front half is in the universe of Nazi bees."

- A. A. Milne

"The warpship wreck had inverted space and time, marooning me on a single day, far from the present. Still, at least I had my Man Sideways."

- Daniel Defoe

I'M TRANSMITTING THIS FROM YOUR FUTURE. STOP RIGHT NOW, ALL RIGHT? YOU DON'T WANT TO CARRY ON WITH THIS. TRUST ME, IT'S REALLY NOT WORTH IT.

- Salman Rushdie

"Its back shines like quicksilver," said Ahab, "and in its gut, Hell's own wrath. Aye, a uranium coin for the first to spy the Red October!"

- Herman Melville

riverrun, in stream of conscientiousness, wilfitfully scarding sense to halve the Horror from 'Cross Eternity and its rrravaging of rrreason

- James Joyce

Once she'd dug a well for the villagers, adding her own DNA drones to the water was simple. Oh yes: this town would be *exactly* like Alice.

- Nevil Shute

D'Artagnon's faith in "one for all, and all for one" was only tested when he felt the Musketeer Gestalt surreptitiously borrowing his liver.

- Alexander Dumas

"Yet on some whim, I Judas' nipple brushed / That cold tomb swung aside, and there revealed / A lower level still, that's like the Batcave."

- Dante

"You fool," growled his anti-world counterpart, as its claws tore through his duffelcoat. "Did you really think yours was the Darkest Peru?"

- Michael Bond

"Nanocure Kurtz-G318 has gone native inside the Congolese ambassador. We think it's arranged the cancer cells into its own personal empire."

- Joseph Conrad

Among those at the Paris barricade was Les Miserables, a '70s club comic who'd become unstuck in time. France remembered him subconsciously.

- Victor Hugo

The golden age ended in 1963, when a study found that not every tank-engine required AI to be efficient, especially on island branch-lines.

- The Reverend W. Awdry

Mina accepted her fate after realising that Dracula means "Son of the Dragon", and that he could give her rides "like in Neverending Story".

- Bram Stoker

"Reader: I married him. This was considered daringly metatextual, yet it was a preferable narrative device to the Fourth-Wall Siege Engine."

- Charlotte Brontë

Its four arms became helicopter blades; its turret, a great cannon. But Rotatron, leader of the Windmillcons, was about to meet its nemesis.

- Cervantes

El-Ahrairah gazed beyond the portal, at all the worlds his people would infest. From this day, he'd be the Prince with Nine-Billion Enemies.

- Richard Adams

"Long before becoming Emperor, I visited the Sybil at Cunae. She revealed to me a monstrous prophecy about a place called the Night Garden."

- Robert Graves

Published on May 11, 2011 23:00

April 30, 2011

Invader Debrief

Later, back at Silence HQ...

"Jesus, Barry. For someone who calls himself 'Silent', you've got a f***ing mouth on you."

"Er... what?"

"You should kill us all on sight? You actually said you should kill us all on sight? Into a mobile 'phone? Christ, why didn't you tell them to shag your sister while you were at it? It doesn't even make sense within the context of the dialogue, you twat!"

"Look, I'm sorry, all right? I was just... y'know... trying to sound hard. I wanted them to know we were going all the way with this. It's not like I meant to RUIN ALL OUR PLANS FOR WORLD CONQUEST."

"You're doing it again, Barry."

"I... oh yeah."

"Unbelievable. We've been working on this since the Stone Age, somehow. Jagaroth, Fendahl, Last of the Daemons... we've seen 'em all off. Millions of years spent on a foolproof masterplan. But ohhhh, no. It can't withstand Big-Mouth Barry, can it?"

"Okay, fine. You're upset. I'm upset too, yeah? You know I'd never deliberately do anything to SABOTAGE A SCHEME THAT'S BEEN AEONS IN THE MAKING."

"Barry!"

"Crap. All right, if you've really got to know. It's my Tourette's, it always gets worse when I'm stressed. There's no need to BITE MY BALLS... ow."

"GO AND WATCH MISFITS...! Bugger."

"GO AND WATCH MISFITS...! Bugger."

"Jesus, Barry. For someone who calls himself 'Silent', you've got a f***ing mouth on you."

"Er... what?"

"You should kill us all on sight? You actually said you should kill us all on sight? Into a mobile 'phone? Christ, why didn't you tell them to shag your sister while you were at it? It doesn't even make sense within the context of the dialogue, you twat!"

"Look, I'm sorry, all right? I was just... y'know... trying to sound hard. I wanted them to know we were going all the way with this. It's not like I meant to RUIN ALL OUR PLANS FOR WORLD CONQUEST."

"You're doing it again, Barry."

"I... oh yeah."

"Unbelievable. We've been working on this since the Stone Age, somehow. Jagaroth, Fendahl, Last of the Daemons... we've seen 'em all off. Millions of years spent on a foolproof masterplan. But ohhhh, no. It can't withstand Big-Mouth Barry, can it?"

"Okay, fine. You're upset. I'm upset too, yeah? You know I'd never deliberately do anything to SABOTAGE A SCHEME THAT'S BEEN AEONS IN THE MAKING."

"Barry!"

"Crap. All right, if you've really got to know. It's my Tourette's, it always gets worse when I'm stressed. There's no need to BITE MY BALLS... ow."

"GO AND WATCH MISFITS...! Bugger."

"GO AND WATCH MISFITS...! Bugger."

Published on April 30, 2011 22:00

April 23, 2011

Cheap Shot Redux

Same schtick, but now with analysis.

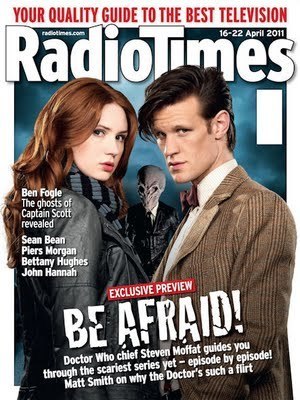

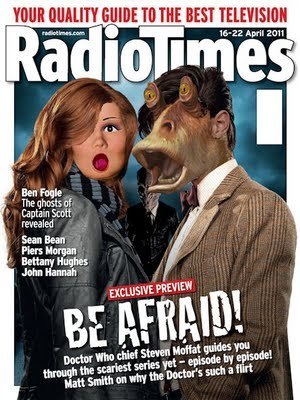

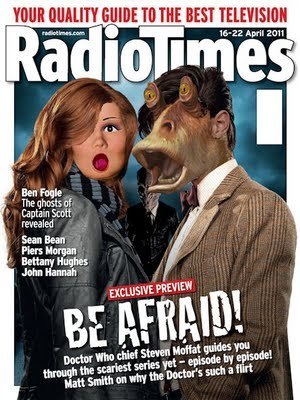

The cover of this week's Radio Times...

...and what it looks like to me.

That piece of Radio Times cover sabotage was instinctive, if you can use the word "instinctive" to describe something that ultimately took about half an hour on PhotoShop. The point being, that really is how I see modern-day Doctor Who: the adventures of Jar Jar Binks and a blow-up doll, trying to look as if they smoulder against a bad CGI background. I was planning to leave it at that, but...

...but another week's exposure to the trailer has led me to realise something. Specifically, why the Gungan Doctor seems to fit this picture so perfectly.

Well, here we go again.

We know, by now, that there are certain... all right, let's be positive, and call them "tropes" rather than "clichés" or "acts of desperation". Certain tropes that Moffat will always use, the most obvious being the "going back in time and messing about with history in order to produce the desired result" idea. '90s-era fandom will know that this began with his Decalog story "Continuity Errors", the first (official) thing he ever wrote for Doctor Who, and magnificent in itself. "In itself" because he's pirated bits of it for almost everything he's done since. "Curse of the Fatal Death", "The Girl in the Fireplace", "Blink" (and, more tellingly, the Sally Sparrow story that "Blink" was based on), "Silence in the Library", and then - finally, or at least, I hope it's finally - "A Christmas Carol", not so much a cannibalisation as a remake with icing. Although the most cloying example is obviously "The Eleventh Hour", because the moment you see two unnamed "Girls" in the Radio Times cast list, you know they're going to be two previous versions of the new companion and you know the Doctor is going to spend the whole twatty hour going backwards and forwards while being surprised by things that don't even surprise the audience. Even a mook like Charlie Brooker called it "business as usual".

Easy to see why Moffat is pulled towards this kind of thing, though. We can cover up its obviousness by giving it a cute nickname like "timey-wimey, in-and-outey", but we all instinctively know it's the product of a background in comedy. Jack Dee, during his BBC Britain's Best Sit-Com segment, argued that Fawlty Towers is the Perfect Farce. Rubbish: Moffat's comedy writing shows the same precision, but he can do it in four dimensions, effectively sticking a turkey down the vicar's trousers EVEN BEFORE THE VICAR WAS BORN. It's what he's good at. A comic structure that intersects with itself in time, space, and slapstick.

Arguably, it's the only thing he's good at.

Put in the spotlight, Moffat returns to a stimulus-response kind of thinking. If he does something that works, something that people like, then he does it again: this is how comedy writers, those who demand an instant reaction from the audience, are primed to think. He once told me that he found writing drama incredibly easy after writing comedy. Therein lies most of the problem. Drama isn't easy, it's just harder to see when you're not doing it properly. If you get comedy wrong, then the audience won't laugh. If you get drama wrong, then... hey! They'll still applaud politely. If your drama passes the time and doesn't frighten the horses, it'll get recommissioned. That doesn't mean it was actually dramatic, or that it hit its target.

No, this is getting too grandiose, so let's stick to the Moffat Era in specific. Moffat is trained to repeat what works. He specifically looks at the kind of thing People Who Watch Doctor Who like, and what might appeal to them again in future. In terms of People Who Watch Doctor Who, he's homed in on two main groups. One of which is a perfect partner for his going-back-in-time-and-fiddling-about model (what I'll hereafter call the Farcical Version, for the logical reason and because I enjoy it). That group is, of course, children.

It worked brilliantly in "The Girl in the Fireplace", and the logic seems sound. Four points here. Children watch Doctor Who; children are scared by Doctor Who; children idolise the Doctor; therefore, get the Doctor to interact directly with a child who's being threatened by a scary monster in the dark, and it'll be a winner. Perfect, yes? So much so that it can be repeated at every opportunity in order to get the children on-side, just like comedy writers are self-programmed to. "Silence of the Library" (again), "The Eleventh Hour" (again), "A Christmas Carol" (again), and now - if the trailer's anything to go by - "The Impossible Astronaut". All of them bring the Doctor into direct contact with an audience-substitute child who's being menaced by something, since the suggestion is that this is what every under-twelve secretly wants.

And it's this tendency that truly links Moffat to his soul-twin, Neil Gaiman. Gaiman never had the excuse of being a comedy writer. He just wanted to spend the early '90s nicking all of Alan Moore's best ideas and then hanging around conventions in sunglasses, trying to impress the chicks. But modern Who-cynicism works the same way. Gaiman's odious Books of Magic provided, pre-Harry Potter, a bespectacled future messiah exactly like the typical reader of comic-books who used to get bullied at school; worse, Sandman turned Death (i.e. the obsession of all literate teenagers, especially the sort of pseudo-goths who might be interested in "alternative" culture) into every Teenage Boy Outsider's perfect blow-up doll and every Neurotic Girl Outsider's vision of what she wants to look like when she's at university. You can call this sort of drivel "writing" if you like, but it's actually closer to what advertising agencies do when they want to sell spot-cream. Moore was (and still is) a sometimes-genius who might get residual highs from licking his own eyeballs; Grant Morrison was (and may still be) a spiky little punkette who often got things wrong, but always went "RAAAAH!"; while Gaiman has continually been that awful boy at sixth-form who tried to get into girls' pants by claiming that he'd rewritten the poems of Lord Byron to fit the meter of "The Joshua Tree". Yes, I went to college in the late '80s. The analogy still holds.

Moffat, meanwhile, sees children as half of his target demographic. This is also a problem, but mainly because his foundations are shaky. Let's look at those key four points again.

1. Children watch Doctor Who. Yep, that's true.

2. Children are scared by Doctor Who. Ahhhhh. Here we're walking on thin ice, if not clingfilm. In the '60s, children were definitely scared by Doctor Who: the sensation of never-before-seen luminous worlds and never-before-heard radiophonic sounds, coming out of a crackling box in the corner of the room, drove the young 'uns under the furniture. In the '70s, less so. I was never scared by it, as a child. As I (and many others) have aleady noted, I was terrified of Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" video, but never of Daleks. Colour, and the sense of Doctor Who as an extension of Top of the Pops without Queen, made it exotic rather than pant-wetting. The younger viewers of the '80s remember being interested, not frightened. Post-2005...? Modern Doctor Who is, to the excited kidling, about playing games with fear rather than actually being afraid. Eight-year-olds in the time of Eccleston looked at the Autons and went "YESSSSSS!", but they didn't hide behind the sofa. "Blink", for all its terrible sitcom dialogue and dribbling "character" scenes, is a brilliant playground game. But it didn't cause nightmares. "Keep watching that statue, Jay! We'll build something to stop it. No, don't turn round! DON'T TURN ROUND!"

In other words, the idea that children are scared by Doctor Who is based on the nostalgia of grown-ups, not on the way the programme works at its core. Let's face it, we're in 2011, where even pre-watershed-TV is full of CGI horror that the thing from "The Lazarus Experiment" is barely going to scratch. Any movie on Channel 5 should give you the same mix of special effects and things going "bleuurgghhh". The children aren't scared, they want to act in a manner that allows them to seem scared, primarily so they can fight it: the idea that Doctor Who is a scary programme, though it may have led to a typically Pavlovian tendency for the Radio Times to squeal "IT'S THE SCARIEST ONE YET!" every other week, is based on the folk-memory of old gits like us. And likewise...

3. Children idolise the Doctor. No, they don't. Fans do, generally when they get older. Eight-year-olds don't want David Tennant to burst into their rooms and protect them: that's the desire of a rather more mature age-group, on both sides of the gender line (this is why "The Girl in the Fireplace" pulled it off, and why it's significant that the Little Girl rather unbelievably snogs the Doctor as soon as she's a Big Girl). Children don't ask for the Doctor's intervention, because children want to be able to do the job themselves. This may be why so many Moffat Era stories remind you of Time Bandits, but why none of them have ever been as good. Terry Gilliam at least knew that the child should be the smart one, not the one who's patronised for his intelligence by a particularly nerdy grown-up.

4. The final point is the most crucial: the idea that you make Doctor Who popular with children by getting the Doctor to interact directly with a child. And it's this that brings us back to what George Lucas did in 1999.

Now, when Lucas made The Phantom Menace, he specifically wanted to make an "innocent" film. He wanted to make an adventure story that focused on childhood, in the same way that Attack of the Clones focused on teenage angst and Revenge of the Sith focused on the failure to become a proper adult. In this, he succeeded. Geeks of all colours loathed Episode I, largely because they'd spent the previous twenty years pretending that Han Solo was the important one, and nauseating adolescents always hate to admit that anything designed for children might be any good. (When I was fourteen, I started hating the Muppets. Jesus! Can you imagine that...? Nobody good hates Muppets. Or Bagpuss.) Yet children rather liked The Phantom Menace, because it was... you know... fun. Not "dark". Not "scary". Not "full of Freudian terror, like we pretend The Empire Strikes Back is these days". Just... fun.

Yet Uncle George made two mistakes, or rather, one mistake twice. Since he was thinking about childhood, he included characters specifically designed to accord with children. This is always a bad move. Even in his own universe, no kid watching the original Star Wars needed prompting this way. Most children circa 1977 empathised with R2-D2, a sarcastic little bugger who saw things from a child's perspective, who could tell when the grown-ups were going astray and gently prod them in the right direction. Those with a more dynamic streak could empathise with Luke Skywalker as well, with his perpetual my-family-are-dead-and-now-I-have-to-save-the-galaxy-hooray-I-mean-boo-hoo demeanour. On a less boyish level, Leia was the first fairytale princess who kicked back. Children don't particularly like watching other children, but tend to stick with characters who express a child's frustration on a larger scale. The newly-spawned (all right, especially newly-spawned boys in this case) who watched The Phantom Menace generally sided with Little Obi-Wan rather than Anakin, since Ewan MacGregor had a Liam Neeson-shaped father-figure to remind them of family life, but enough will of his own to make them feel he was "one of them". They didn't give a stuff about Anakin. And as for Jar Jar Binks...

Jar Jar Binks was designed to be Every Child's Imaginary Friend, a ditzy, rubbery-faced, comical alien. Real children, of course, don't respond to that any better than the nauseating adolescents did. The point of an imaginary friend is that you want to be that friend: you don't want to laugh at him for pulling faces, you want to be able to fly / walk through walls / stop time like he does. Lucas got more right than we acknowledge, but this was his biggest error. Ironic, then, that Moffat makes it repeatedly. By forcing the Doctor to interact with children, he really has made the Doctor a Jar Jar figure. If he does goofy things in your own kitchen, then the Doctor becomes unnecessary and rather annoying. We want to see him explore the universe on our behalf, we don't want him to be exactly like the magician who came to our sixth birthday party and did that rubbish trick with the string.

Again, remember that the "Fireplace" logic is ultimately there for us, for grown-ups who've ended up resorting to fetishism. Just like terrible party magicians are never hired by their audience, but by the audience's parents. And when the Doctor makes things worse by delivering horribly misplaced macho action-movie dialogue ("there's one thing you don't put in a trap... me!!!"), you've got a script full of frustrated adolescence being delievered by characters who'd be better off saying "exsqueeeeeeze me!" and admitting that there's nothing remotely "dark" about it.

I'll wind this up with a personal reflection. Halfway through last year's season, I was on a train coming back from central London, sitting just behind a family who'd spent the day at the Natural History Museum. The mother mentioned Doctor Who, and the girl-child (I'd estimate eleven years old, but I'm not an expert) said in a semi-interested sort of way: "Yeah... yeah, I don't always watch it." This makes sense now, but would've been bizarre only three years earlier. I instinctively connect the urge to watch Doctor Who with the urge to go to museums. They're both about curiosity: rightly or wrongly, I feel that wanting to examine a brontosaurus is much the same as wanting to know how someone from the fiftieth century might pretend to be an ancient Chinese god, and I can't put myself in the place of someone who'd be interested in one but not the other. In the Moffat Era universe, however, curiosity isn't a criterion. The Doctor never explores; he just changes the timeline until the universe suits him. The Doctor never discovers; he knows all the answers, so that he can make flip comments without having to think about what he's actually saying. The Doctor never investigates; he disposes of monsters because he's the Doctor, and therefore wins by default.

If you wanted to be really cynical, you could say that the Matt Smith version is the perfect Doctor for the consumerist world, making the universe comfortable for all the people who want comfort without imagination. But that tendency started on Tennant's watch. Moffat simply doesn't want to argue, because asking questions doesn't get an instant audience response, even if it makes better television and (ultimately) better people. In this version of the universe, libraries and museums are there to be "creepy", not places you might actually enjoy or (God forbid) learn anything from. "Silence in the Library" forgets it's even about a library after the first ten minutes, and switches to a subplot about the Doctor communicating with a child via a TV set. "The Big Bang" could only have been written by someone who thinks of museums as alien rather than an instinctive second home. Moffat used to be a schoolteacher, of course. I'll let you draw your own conclusions about that.

So if it isn't really doing anything for the children who keep appearing in it, then where's Doctor Who really being aimed...? The answer's fairly obvious: it's Twilight with time-travel, more interested in the Doctor's love-life than going anywhere outside the sci-fi comfort zone. That's "sci-fi" in the sense of "sci-fi TV", naturally, not in the good way. We recall that Moffat refuses to read SF literature, which he considers saa-aad. This is why the new series is filled with all the clichés that a mid-'90s geek would like: Area 51, "tragic" Doctor-driven story-arcs, mysterious transdimensional love affairs, and - yes - Neil sodding Gaiman.

So the final judgement on the Moffat Era, at least as it stands, will fit into two neat sentences. At its best, Doctor Who was a programme for intelligent children. Now it's a programme for very stupid adolescents.

The cover of this week's Radio Times...

...and what it looks like to me.

That piece of Radio Times cover sabotage was instinctive, if you can use the word "instinctive" to describe something that ultimately took about half an hour on PhotoShop. The point being, that really is how I see modern-day Doctor Who: the adventures of Jar Jar Binks and a blow-up doll, trying to look as if they smoulder against a bad CGI background. I was planning to leave it at that, but...

...but another week's exposure to the trailer has led me to realise something. Specifically, why the Gungan Doctor seems to fit this picture so perfectly.

Well, here we go again.

We know, by now, that there are certain... all right, let's be positive, and call them "tropes" rather than "clichés" or "acts of desperation". Certain tropes that Moffat will always use, the most obvious being the "going back in time and messing about with history in order to produce the desired result" idea. '90s-era fandom will know that this began with his Decalog story "Continuity Errors", the first (official) thing he ever wrote for Doctor Who, and magnificent in itself. "In itself" because he's pirated bits of it for almost everything he's done since. "Curse of the Fatal Death", "The Girl in the Fireplace", "Blink" (and, more tellingly, the Sally Sparrow story that "Blink" was based on), "Silence in the Library", and then - finally, or at least, I hope it's finally - "A Christmas Carol", not so much a cannibalisation as a remake with icing. Although the most cloying example is obviously "The Eleventh Hour", because the moment you see two unnamed "Girls" in the Radio Times cast list, you know they're going to be two previous versions of the new companion and you know the Doctor is going to spend the whole twatty hour going backwards and forwards while being surprised by things that don't even surprise the audience. Even a mook like Charlie Brooker called it "business as usual".

Easy to see why Moffat is pulled towards this kind of thing, though. We can cover up its obviousness by giving it a cute nickname like "timey-wimey, in-and-outey", but we all instinctively know it's the product of a background in comedy. Jack Dee, during his BBC Britain's Best Sit-Com segment, argued that Fawlty Towers is the Perfect Farce. Rubbish: Moffat's comedy writing shows the same precision, but he can do it in four dimensions, effectively sticking a turkey down the vicar's trousers EVEN BEFORE THE VICAR WAS BORN. It's what he's good at. A comic structure that intersects with itself in time, space, and slapstick.

Arguably, it's the only thing he's good at.

Put in the spotlight, Moffat returns to a stimulus-response kind of thinking. If he does something that works, something that people like, then he does it again: this is how comedy writers, those who demand an instant reaction from the audience, are primed to think. He once told me that he found writing drama incredibly easy after writing comedy. Therein lies most of the problem. Drama isn't easy, it's just harder to see when you're not doing it properly. If you get comedy wrong, then the audience won't laugh. If you get drama wrong, then... hey! They'll still applaud politely. If your drama passes the time and doesn't frighten the horses, it'll get recommissioned. That doesn't mean it was actually dramatic, or that it hit its target.

No, this is getting too grandiose, so let's stick to the Moffat Era in specific. Moffat is trained to repeat what works. He specifically looks at the kind of thing People Who Watch Doctor Who like, and what might appeal to them again in future. In terms of People Who Watch Doctor Who, he's homed in on two main groups. One of which is a perfect partner for his going-back-in-time-and-fiddling-about model (what I'll hereafter call the Farcical Version, for the logical reason and because I enjoy it). That group is, of course, children.

It worked brilliantly in "The Girl in the Fireplace", and the logic seems sound. Four points here. Children watch Doctor Who; children are scared by Doctor Who; children idolise the Doctor; therefore, get the Doctor to interact directly with a child who's being threatened by a scary monster in the dark, and it'll be a winner. Perfect, yes? So much so that it can be repeated at every opportunity in order to get the children on-side, just like comedy writers are self-programmed to. "Silence of the Library" (again), "The Eleventh Hour" (again), "A Christmas Carol" (again), and now - if the trailer's anything to go by - "The Impossible Astronaut". All of them bring the Doctor into direct contact with an audience-substitute child who's being menaced by something, since the suggestion is that this is what every under-twelve secretly wants.

And it's this tendency that truly links Moffat to his soul-twin, Neil Gaiman. Gaiman never had the excuse of being a comedy writer. He just wanted to spend the early '90s nicking all of Alan Moore's best ideas and then hanging around conventions in sunglasses, trying to impress the chicks. But modern Who-cynicism works the same way. Gaiman's odious Books of Magic provided, pre-Harry Potter, a bespectacled future messiah exactly like the typical reader of comic-books who used to get bullied at school; worse, Sandman turned Death (i.e. the obsession of all literate teenagers, especially the sort of pseudo-goths who might be interested in "alternative" culture) into every Teenage Boy Outsider's perfect blow-up doll and every Neurotic Girl Outsider's vision of what she wants to look like when she's at university. You can call this sort of drivel "writing" if you like, but it's actually closer to what advertising agencies do when they want to sell spot-cream. Moore was (and still is) a sometimes-genius who might get residual highs from licking his own eyeballs; Grant Morrison was (and may still be) a spiky little punkette who often got things wrong, but always went "RAAAAH!"; while Gaiman has continually been that awful boy at sixth-form who tried to get into girls' pants by claiming that he'd rewritten the poems of Lord Byron to fit the meter of "The Joshua Tree". Yes, I went to college in the late '80s. The analogy still holds.

Moffat, meanwhile, sees children as half of his target demographic. This is also a problem, but mainly because his foundations are shaky. Let's look at those key four points again.

1. Children watch Doctor Who. Yep, that's true.

2. Children are scared by Doctor Who. Ahhhhh. Here we're walking on thin ice, if not clingfilm. In the '60s, children were definitely scared by Doctor Who: the sensation of never-before-seen luminous worlds and never-before-heard radiophonic sounds, coming out of a crackling box in the corner of the room, drove the young 'uns under the furniture. In the '70s, less so. I was never scared by it, as a child. As I (and many others) have aleady noted, I was terrified of Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" video, but never of Daleks. Colour, and the sense of Doctor Who as an extension of Top of the Pops without Queen, made it exotic rather than pant-wetting. The younger viewers of the '80s remember being interested, not frightened. Post-2005...? Modern Doctor Who is, to the excited kidling, about playing games with fear rather than actually being afraid. Eight-year-olds in the time of Eccleston looked at the Autons and went "YESSSSSS!", but they didn't hide behind the sofa. "Blink", for all its terrible sitcom dialogue and dribbling "character" scenes, is a brilliant playground game. But it didn't cause nightmares. "Keep watching that statue, Jay! We'll build something to stop it. No, don't turn round! DON'T TURN ROUND!"

In other words, the idea that children are scared by Doctor Who is based on the nostalgia of grown-ups, not on the way the programme works at its core. Let's face it, we're in 2011, where even pre-watershed-TV is full of CGI horror that the thing from "The Lazarus Experiment" is barely going to scratch. Any movie on Channel 5 should give you the same mix of special effects and things going "bleuurgghhh". The children aren't scared, they want to act in a manner that allows them to seem scared, primarily so they can fight it: the idea that Doctor Who is a scary programme, though it may have led to a typically Pavlovian tendency for the Radio Times to squeal "IT'S THE SCARIEST ONE YET!" every other week, is based on the folk-memory of old gits like us. And likewise...

3. Children idolise the Doctor. No, they don't. Fans do, generally when they get older. Eight-year-olds don't want David Tennant to burst into their rooms and protect them: that's the desire of a rather more mature age-group, on both sides of the gender line (this is why "The Girl in the Fireplace" pulled it off, and why it's significant that the Little Girl rather unbelievably snogs the Doctor as soon as she's a Big Girl). Children don't ask for the Doctor's intervention, because children want to be able to do the job themselves. This may be why so many Moffat Era stories remind you of Time Bandits, but why none of them have ever been as good. Terry Gilliam at least knew that the child should be the smart one, not the one who's patronised for his intelligence by a particularly nerdy grown-up.

4. The final point is the most crucial: the idea that you make Doctor Who popular with children by getting the Doctor to interact directly with a child. And it's this that brings us back to what George Lucas did in 1999.

Now, when Lucas made The Phantom Menace, he specifically wanted to make an "innocent" film. He wanted to make an adventure story that focused on childhood, in the same way that Attack of the Clones focused on teenage angst and Revenge of the Sith focused on the failure to become a proper adult. In this, he succeeded. Geeks of all colours loathed Episode I, largely because they'd spent the previous twenty years pretending that Han Solo was the important one, and nauseating adolescents always hate to admit that anything designed for children might be any good. (When I was fourteen, I started hating the Muppets. Jesus! Can you imagine that...? Nobody good hates Muppets. Or Bagpuss.) Yet children rather liked The Phantom Menace, because it was... you know... fun. Not "dark". Not "scary". Not "full of Freudian terror, like we pretend The Empire Strikes Back is these days". Just... fun.