Lawrence Miles's Blog, page 3

January 19, 2013

I think I've already mentioned how my cousin likes buildi...

November 27, 2012

It's obviously the season for temporal décolletage. "Lift...

November 26, 2012

NSFF

This is an undoctored (in every sense) photograph of my favourite... well, what is the word we should use? "Model" doesn't go far enough; "porn star", aside from being a phrase popularised in the '90s to lead young women into a world of pretend-glamour after only a single plying with cocaine, seems to go too far. So we'll stick with the coquettish "adult performer".

Some of you may also wonder why a sophisticated renaissance man like myself would be interested in looking at pahahahahah. Sorry, couldn't keep a straight face.

Some of you may also wonder why a sophisticated renaissance man like myself would be interested in looking at pahahahahah. Sorry, couldn't keep a straight face.

Her name is, for our purposes, Lexxxi Luxe. She currently has two Twitter accounts, one for herself, and one for her two unusually opinionated companions. Anyone who's "enjoyed" her "work" in recent years will be unsurprised by this level of self-awareness, because the third most noticeable thing about her is that apart from walking the line between sexuality and genetic slapstick, she... hmm. Let's put it like this. Men have been known to find themselves distracted by her personality. The words "charm" and "intelligence" have been used. This isn't a classical centrefold: this is the girl you fancied at college. You know. The one studying forensic psychology in that sweater.

Now, thanks to her Twitter stream, we can see the proof. Amongst the various self-portraits of herself in deviously-engineered coiture are pictures like...

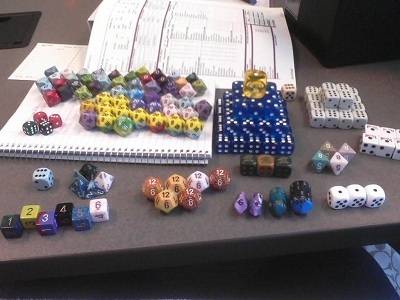

"Lawful-Good Clerics cannot use bras above 38G."

"Lawful-Good Clerics cannot use bras above 38G."

This picture isn't as sexy as the first one, and nobody would suggest otherwise, apart from whatever c***s write The Big Bang Theory. However, it's no less remarkable in terms of either aesthetics (such colour co-ordination...!) or size (I played Dungeons and Dragons for the first time in 1979, when I was seven and the cover of the rulebook was in fucking black-and-white, but even I don't have a dice-pool like that).

I have in my time known many geek-or-gamer women who've been built like sexy Ogron Gods, or who've done things that walk the line between exciting and unsanitary, or both. (I don't know why I keep using the "walk the line" metaphor. If she were standing on a line, would she even be able to see it? We move on.) This, though, is the first time I've come across someone who's joint-unapologetic about (a) having a functional knowledge of trading-card games and (b) allowing footage of herself on the internet in which she's being ****ly *****ed by a **** ******* that ****s like the Bandril Ambassador.

O brave new world that has such people. True, she's already married. But that's never stood in the way of any woman becoming an eminent sex symbol. Surely, nothing on Earth or in any of 1d4 shadow-realms could prevent her taking her rightful place as the ideal (Fighting) Fantasy Figure.

Oh, wait! She's just uploaded a picture of herself in her new T-shirt.

Yeah, he gets on my tits as well.

Yeah, he gets on my tits as well.

What's almost sweet about this is the Twitter response it received from UK BBW Lover (a man walking a line of his own, I feel): "love the t-shirt. 4th & 10th doctor are my favourites though". That's clearly not me, so don't even bother joking.

A personal note, however. It's no great surprise that I'm single, and have been for quite a while, but there's something I've had to accept about this situation: although everyone expects to have more difficulty finding a partner as they get older, I've got... an additional issue. Let's be honest, you'd probably expect anyone with whom I'm in a relationship to have at least a basic knowledge of all ten proper Doctor Whos (not in a "setting tests" way, more in a "that's the sort of person I'm likely to meet anyway" way), and my past history bears this out. However...

...what happens when Doctor Who is specifically targeted at women in the most cynical way conceivable, like Twilight if Stephenie Meyer had been an emotionally-retarded predator rather than just a bit thick? It's a problem that can probably only be understood by the maniacally obsessive, yet imagine a similar situation without the sci-fi bollocks; imagine being a (male, largely heterosexual) musician in a world where only a minority of people are interested in music, and all the women among them like One Direction. Not accidentally, there are more fangirls in the world than ever before, all of them just throbbing with hormonal squee. And squee is poison to my kind. From c. 2008, the one type of woman I absolutely can't go anywhere near is a woman who likes Doctor Who. Or Star Wars, but that's another issue.

By now, I've come to terms with this. It's fairly clear that, for everyone's benefit, I should stay away from any single woman connected with fandom on any level whatsoever. Certainly in the real world.

But now they're in pornography too...?

Also, if you type "Lexxxi Luxe" into Google Images, this is the first picture you get. You sick, sick people.

Also, if you type "Lexxxi Luxe" into Google Images, this is the first picture you get. You sick, sick people.

November 11, 2012

Barry Letts in the Underworld

Nice to know that sometimes, nature can do CSO that's even more unconvincing than "Planet of the Spiders".

Now look at the photo accompanying the National Geographic article: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2008/11/crystal-giants/shea-text. And try to work out why nothing in modern SF looks quite so improbably alien, when this is just 300 yards under the planet you're on.

October 31, 2012

...

Because I just had the worst thought in the entire history of time.

October 20, 2012

In Case You Didn't Believe Us...

http://www.rhymney-silurian-male-choir.org/

October 17, 2012

About Red Dwarf

From a distance, it's not much of a stretch. In the great schism of the 1990s, when letters were sent to DWM suggesting that future Doctor Who should be as much like Star Trek: The Next Generation as possible (and then, after the TV movie, that it should be as unlike The X-Files as possible), Doctor Who and Red Dwarf were seen as pod-brothers: both BBC, both sci-fi. I never believed it then and I don't believe it now, but you probably guessed that, not least because I loathe what's come to be called sci-fi. But I did watch the first episode of Red Dwarf in 1987, as did most of the boys in my class [ADVERTSING SMALL PRINT - girls not included in this survey - boys stay on one side of the classroom and girls on the other - boys may not cross over and talk to girls because that means they're gay somehow]. Still a few years away from the idea of "Cult TV", we just thought it was funny, and different, and unexpected. Younger readers may like to note that although the '80s were exactly as awful as you've gathered, "different" and "unexpected" were still good things then.

Because that's what comedy programmes were / are supposed to be, surely? We had the pleasure of watching "The End" and saying "oh, riiiight... is that guy coming out of the ventilator shaft descended from the cat, then?".

Not untypically, the '90s acceptance of Red Dwarf as "Cult" and "sci-fi" is what slit its throat. In the beginning, Grant and Naylor perceived it as "Steptoe and Son in space". The creators of Porridge pointed out circa 1990 that the essence of sitcom is "two blokes who don't like each other trapped in a room": though both the Fletch / Godber relationship and the media's partial realisation that WOMEN EXIST have caused us to redefine our terms, it's still true that sitcom requires a sense of entrapment if it's going to work. The Grant-Naylor pushmepullyou considered "Marooned" one of the best of the early episodes, and I'd posit it as the best... but even though "Marooned" is essentially two blokes who don't like each other trapped in a room, both the scenario in which they're trapped and the nature of their conversation couldn't exist outside of a space-travelling, history-mangling context. "Polymorph" is more popular with sci-fi people, yet even this takes the claustrophobia of The Thing and uses it for laughs.

Look at the way I phrased that, and it tells you everything. "More popular with sci-fi people." Quite. Despite its authors' claim that Red Dwarf was a working-class sitcom, by the early '90s it had become Cult TV for middle-class university students. I have no problem with this, being massively middle-class myself, but the sense of delusion is startling. It began as Steptoe and Son, using science-fiction ideas to set up otherwise implausible situations; by Red Dwarf VI, it believed it was Star Trek: The Next Generation with jokes. The gulf between the two is enormous. "Emohawk" is a work of fan-fic. "Gunmen of the Apocalypse", after the first few minutes of grotesque VR-sex (a new source of humour in the early '90s), is a very bland episode of an SF series that isn't dramatic enough to be drama and isn't funny enough to be comedy. '90s Red Dwarf fans, by that stage as insular as '90s Doctor Who fans or '90s Iron Maiden fans, voted it one of their favourites. Nobody else gave a toss. (Seeing it this way, "Back to Reality" might be considered the fulcrum of the whole series, the point where comedy and SF balanced perfectly. Of course, we didn't have the term "just before it jumped the shark" in those days.)

And then, as you all know, Red Dwarf VII crossed the line. An obsession with making sci-fi TV "but funny", filmlooked for international slickness even though it alienated the casual audience and removed the last traces of sitcom from a programme that was never, ever designed to work as a "space" show... by this stage, Red Dwarf fans were already seen as the kind of gits who expressed themselves through T-shirts from Forbidden Planet rather than conversation, much as Python fans had been since the '80s. The seventh series made even them too embarrassed to admit to liking it. The eighth was an improvement - in some ways taking the Porridge point rather literally, in others ruining it all with a two-parter involving a f***ing great dinosaur and a cliffhanger that just looked silly - but it came too late. Red Dwarf had pretended to be cool with a hint of monster. It had ended up too geeky even for geeks.

[We will assume the ninth didn't really happen.]

The big surprise of Red Dwarf X, then, is that isn't awful. None of the excitement or newness of I-III, yet still, maybe something of IV-V. This isn't a review, so I won't review it: I'm more interested in its structure. The episodes are designed as sitcom in space, not sci-fi with jokes. The "exterior" shots are now CGI rather than modelwork, and you can argue amongst yourselves as to whether that makes them more or less interesting, even though the answer is obviously less. But everything within the ship is on the small scale, the almost-human level. So much so that when the episode three trailer informs us of the crew [time-travelling / entering a VR / having a mass hallucination] and meeting Jesus, the disappointment's nearly crippling. Then again, even in the early years, they were allowed one day out per series.

The point remains that Red Dwarf X has failed to be terrible simply because it's cramped, and understated, and... well... cheap. "Necessity is the mother of invention" is used to defend all manner of cackpole that didn't turn out the way its creators intended, but can we really deny that things become horribly boring when we've got the capability to do anything? You've presumably read this blog before, so you presumably know what I'm thinking about. Red Dwarf gives us a much clearer example, though. Red Dwarf VII had free reign (there was even a snide-but-backfiring comment about the ship having all the parts it was meant to have before the JMC / BBC stripped it back), as a result of which, it became self-parody. Reassign it to Freeview with what we assume is a minimal budget, and suddenly it's at least focused again.

One final question, irrelevant to much of the above, but something I find interesting just because I like to think about the way people think. If you look at early-phase Doctor Who (certainly the '60s, but leaking into the '70s), the worst thing that can happen to you - the very worst imaginable horror - is to have your consciousness invaded. The trouble is, "mind control" has become so hackneyed in the last half-century that we tend to think of it as the desperate act of a desperate scriptwriter. Yet it meant something tangible, something terribly serious, at a point when (a) psychology was only just establishing itself as a major factor in human concerns after years of being a specialist interest, (b) world powers were being shown to actively employ it as a weapon, and (c) Western culture believed in the notion of people being able to govern themselves rather than just "consuming". As That Tat Wood pointed out, one of the reasons Doctor Who writers used the mind control trope without presenting it as the work of Commie infiltrators was that Doctor Who writers were the kind of people who read a lot of books. Reading promotes an inner voice, and an inner argument. Anything that overrides that argument is a terror beyond all other terrors. Today, mind control is generally presented as A Bad Thing for fading historical reasons (Nazism and Stalinism, even though neither did as much in the field of thought-manipulation as democratic America), unless it's the work of terrorists who want to deprive you of the freedom to choose between Virgin or Sky (the CSI version of brainwashing).

Yet in Red Dwarf, the great fear is of foreknowledge, of predestination. We're trapped by who we are, and by what we're absolutely, inescapably bound to do. "Bound" in its truest sense, too, the sense that you're tied to your future. We could take the characters' own immutable shallowness to be a sign of this, but the idea of being trapped in your destiny occurs as early as the second episode ("Future Echoes", as if most of you didn't know that). It's an idea repeated throughout the series: "Justice" ends with a rant about free will that's undercut by a pratfall which suggests an apology on behalf of the writer/s for explaining the point, while "The Inquisitor" gives us a creature that makes us feel guilty for not achieving greatness. As do the parents of one lead character and the fantasies of the other, throughout the whole 25 years and counting. For further examples, look up a list of episodes on the internet - yes, like I just did - and be astonished by the number of events you hadn't even noticed that fit the same pattern.

When Doug Naylor takes charge in the is-it-funny-or-is-it-sci-fi years, this recoil from an inevitable future gets worse. The first three episodes of Red Dwarf VII are about people doing things because destiny demands it, ironically even though the audience-killing "Tikka to Ride" begins with a prologue which explains that none of the futures predicted in previous episodes are an issue any more. A year later, "Cassandra" takes the breaks off. Now "Fathers and Suns" gives us a computer (like Cassandra, female... a male concern, even if we don't realise it?) who'll doom you in advance because she knows you're going to do exactly the same thing if you're given the opportunity.

A recent study, which you can search for yourselves if you think I make all this up, analysed the human relationships in (amongst many others) Beowulf and Hamlet. It found that Beowulf, despite the surfeit of monsters, was more realistic. Why...? Because in the works we call "sagas", be they Nordic or descendants of Nordic, there's never an ending: good things happen, and bad things happen, but they'll keep happening regardless. Despite their recently-assumed moral similarity to Protestant works, they're actually closer to Buddhism, where the wheel keeps turning unless someone can eventually stop it. Shakespearean tragedy, on the other hand, is always set in an enclosed universe where an end-point will be reached, where people will ultimately suffer, where catharsis will be the objective...

...and in this respect, sitcom is tragedy. Every episode is constructed to create catharsis, suffering, and end-point. Doctor Who writers of yesteryear were genuinely mortified by the idea of other people controlling their thoughts, a fear we no longer experience, since we brush it off as being "part of modern culture" (remember, the anti-jingle rant of "The Macra Terror" is about opposition to advertising rather than opposition to some imaginary fascist elite, jingles being a new and worrying presence in British society circa 1966). '60s readers feared different things to '80s-reared comedy scriptwriters. And many of the latter might reasonably be worried about becoming trapped by their own devices.

Doug Naylor among others.

September 28, 2012

The Wormhole Water Wheel

"The First Law of Thermodynamics is, you do not talk about thermodynamics. The Second Law of Thermodynamics is, you do not talk about thermodynamics." - John-Luke Roberts.

We can be sure, at least, that wormholes work. Which is to say, we can be sure we won't look stupid if we bring them up in conversation. We know this because Carl Sagan told us so. Needing a way to bring humans and aliens into Contact, and not wanting to resort to anything silly like spaceships travelling faster than light in real-space, he concluded that the most feasible method of travelling bbbillions and bbbillions of miles in order to meet one's own dead dad was to interpret General Relativity in a rather dynamic way. This idea wasn't new, and the w-word had been used by a rather apologetic John Wheeler in the '50s, but it's informed every generation of nuts-and-bolts sci-fi since 1985. Nobody has yet proved wormholes impossible. In theory, they're still the fastest way to get from A to A-but-on-the-other-side-of-space.

Note the sentiment buried in that logic, though. It's a sentiment - perhaps in more than one sense of the word - that's found even in Sagan's own musings. Not wanting to resort to anything silly like faster-than-light travel. Current Scientific Thinking is an awkward, chimerical thing, always slippery, always mutable, but mutable in surprising ways. Thankfully, and despite the best attempts of creationists to suggest otherwise, it's well aware of its own nature: yet even so, there are principles for which even the most flagellantly self-analytical physicist feels an attraction stronger than reason. You don't mess with the speed of light, even if the Standard Model is incomplete. And you don't try to outwit the Laws of Thermodynamics, especially not the second one.

This last point is interesting for historical reasons. On the surface, the nineteenth century was "just" another era in which science continued to get the upper hand over slack-jawed dribbling assumption, as were the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the early Industrial Revolution (divide those up into smaller mecha-geological periods as you see fit). The difference is that all of these previous movements had put the Arts Scientifick within a Christian framework, or a Muslim framework if you consider what the Islamic world was up to while we were getting medieval on each others' asses. During the 1800s, science realised / was permitted to point out that no monotheistic God was influencing the equations, let alone marking anyone's homework. The most profound effect of this wasn't the rise of atheism, the decline of religion, or some Dawkinsian crusade towards a definitive post-sacred Truth: in a way, quite the reverse. A much more fundamental result was the sensation, now so common that most of us take it for granted, that nobody had prepared a finale.

Consider the consequences. Before the age of Darwin and Maxwell, even science had a millenarian approach to the universe, a belief - never fully defined, never fully formulated - in some carefully-arranged end point. The appropriately God-awful phrase "intelligent design" would describe most scientific thought before the twentieth century, far beyond mere biology. Famously, the Whig model of human existence took it for granted that every epoch was an improvement on the last, and Whig history went hand-in-hand with the notion of scientific progress even as late as the 1960s. We were definitely heading somewhere, towards an inevitable New Jerusalem, if not exactly the New Testament version then certainly a guiding light at the end of time.

And then, within a generation, it transpired that we weren't. Evolution may not have been an entirely random process, but the understanding of natural selection showed that nobody was making plans. It was as if the cosmos had left us at a motorway service station with £3.50 in sandwich-money, then driven off into the night (a suggestion there of abandonment by parents, but we'll come to that). And if evolution was bad, entropy was catastrophically non-catastrophic. The Laws of Thermodynamics had become formalised by the mid-1800s. Not only did we not have a final destination, but everything was falling apart faster than it could be repaired. Creation was grinding to a halt, and despite what many of us may have picked up from "Logopolis", it wouldn't make a groovy green CSO effect before it went.

One might think that by embracing the Second Law more passionately than any other principle, the physicists of the world are at worst obsessed with the absolute extinction of all life, at best just very intelligent goths. In fact, the acceptance of entropy is what finally freed science. It must have occurred to the majority of people reading this blog that those with the most apocalyptic religious beliefs, those who both expect and eagerly await a final judgement on Goodies and Baddies, just seem to want their dads to step in and sort everything out. To accept that you're going to die is a form of maturity; to accept that everything dies, but to continue to care about it anyway, might arguably be seen as the greatest achievement of either an individual or a culture. You see what I mean about scientists having a sentimental attraction for certain parts of the cosmic model. Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington described entropy as holding "the supreme position among the laws of Nature". It's impossible to frame this in a context without some sense of emotion.

"There is something lamentable, degrading, and almost insane in pursuing the visionary schemes of past ages with dogged determination... the history of Perpetual Motion is a history of the fool-hardiness of either half-learned, or totally ignorant persons." So wrote Henry Dircks, as long ago as 1861, after he'd made a survey of all those who'd tried to produce infinite work / energy in clear breach of the Laws. Those who've attempted to build a perpetual motion machine, to violate the greatest of inviolables, have traditionally been seen as not only misguided but... delusional. Childish, even. And we have been, of course. Millions, literally millions of human beings since the nineteenth century have attempted to build such machines, not all of them adults. Kathy Sykes, the televisual physicist, admitted that she spent much of her childhood trying to do it with Lego. Leaving aside the point that this clearly makes her the ideal woman, she can hardly be alone.

This in itself tells us something interesting. When grown-ups try to make devices that effectively generate something out of nothing, we can assume they generally do it because some entropic instinct is telling them that FOR CHRIST'S SAKE, I DON'T WANT TO DIE IN THIS INCREASINGLY COLD AND ULTIMATELY FUTILE UNIVERSE. It's hard to imagine a six-year-old having the same impulse, although H. P. Lovecraft may have come close. It seems likely that there's an element of challenge involved here. Tell a child to do anything and they'll do the opposite. Tell an intelligent child that something is impossible - an intelligent child like, ooh, maybe the kind who used to watch Doctor Who when it was about things - and they'll try to prove that it isn't. But even beyond that...

All right, let's ask the question, and let's answer it with our instincts. Pretend you've never heard of thermodynamics; pretend you don't know that Maxwell's Demon is as much a product of superstition as every other kind. Why can't you build a perpetual motion machine?

After all, so much in nature's universe tempts us to believe that it's not just possible, but inevitable. Newton showed that an object set in motion, if left unmolested by gravity, atmosphere, and all those other nuisances of friction you find on Earth, should carry on indefinitely. Sadly those nuisances of friction include any machine you might build in order to exploit the process, but nonetheless, the subconscious message we're given is that Things Go On Forever. All schoolchildren are, or were, taught that if you push an object in outer space then it'll keep moving. Often provoking awkward questions about what happens when it hits the edge of the universe, questions which may be even more tangled now. (I'm not a racist, but do you remember how neat our galactic neighbourhood was before all the dark matter moved in and started overcrowding it? I've heard you can get up to 1.898E27 kilograms of superdense material into one council flat.) With true-but-misleading lessons like these found in most childhoods, is it honestly so ridiculous for someone to believe they can construct a device that literally gives 110%...? Efficiency, that is.

Six years ago, I designed a perpetual motion machine of my own. I didn't actually set out to do this: I was watching a documentary about water wheels (look, I'm Homo BBC4, all right?), and found myself niggled. Two sets of facts, both of which had been explained to me as "true", seemed to contradict each other. The result apparently went against Maxwell's equations, so something was clearly wrong somewhere.

My machine was purely theoretical. It couldn't be constructed on present-day Earth, because it relies on the ability to artificially engineer wormholes. But nobody's ever proved that to be impossible, and if Carl Sagan can accept it as the basis of an argument, then I'm sure you can.

Here's the diagram. And I've already copyrighted it © 2006, so hands off.

It's really very simple. The core of the device is a vertical tube, within the gravitational field of a planet (or any other sizeable body). A projectile, let's just call it a metal ball, is dropped into the tube. It turns the "water wheel", and the energy is stored in whatever medium suits you. After that, the ball falls to the bottom of the tube and enters your wormhole. The wormhole has been arranged, and space-time carefully folded, so that the "exit" of the wormhole is at the top of the tube. Travelling from bottom to top without actually being lifted, the ball begins its journey again. The wheel keeps turning. Infinite energy is produced.

No, I couldn't see the problem either. But I'm one of the half-learned.

The obvious difficulty - I say difficulty, not flaw - is that entropy strikes at the heart of the machine. The ball will wear down the wheel; the machinery will fall apart. But this ceases to be a problem when you realise the vast amounts of energy being produced out of nowhere, more than enough to fuel a self-repair system. Vast energy permits the replacement of matter, so it's an engineering problem, not a problem with the physics. (And if you're prepared to countenance the wormholes, then something clever involving nanites is probably going to be on the cards.) This aside, it all looked moderately rational.

Given my background, however, it seemed... a little unlikely that I'd found a way of punching entropy in the face. I took it to a few of my more academically-scientific acquaintances, and asked them what the problem was. Now, this may be a constant peril when laypersons ask questions about theoretical physics without a BBC2 voice-over to hand, but their answers weren't terribly illuminating. Among other things, they speculated that the gravity would in effect "run out": a difficult proposition for me to grasp, given that every model for gravity I've seen (or do I mean metaphor for gravity...?) has presented it as a side-effect of the nature of space-time, not a finite quantity. I couldn't really worm a de-vagued version out of anyone, and my elementary research into gravitational potential energy didn't help much. The suggestion was also raised that the engineering of wormholes might in itself require infinite energy before infinite energy could be generated, although if you're going to assume that the universal rules re: the warping of space-time have been deliberately fixed in order to protect the Laws of Thermodynamics, then you might as well just write GOD SAYS NO on the diagram.

A few weeks later, I was invited to a book-signing in London. Not just me, natch, since my own gravity isn't yet sufficient to pull in a crowd on my own. I was there signing (among other things) About Time; seated next to me was the author of The Science of Doctor Who, the sort of book that everyone had been expecting for ages, but apparently rushed into production after the 2005 series bulldozed everything else in broadcasting while standing on ITV's throat. I was, I admit, rather unfair that afternoon. As you may know, The Science of Doctor Who was a rather - ahem - svelte book, whereas About Time eventually took up six volumes and increasingly felt as if it were made of dwarf-star alloy. Its multi-million-word bulk had already covered most of the pop-science areas in The Science of, and this allowed me to show off like nobody's business. "Oh, so you've gone for quantum entanglement as the most likely answer to teleportation?" I'd say. "We discussed that possibility in the essay under 'Nightmare of Eden', but we concluded that..." And so on.

Nevertheless, my neighbour during that signing was a proper science writer (and, later, the author of How to Destroy the Universe... I don't think I was that mean to him). At the end of the day, I drew my design on a piece of paper - I remember it being a napkin, but probably only because it's always a napkin in these stories - and asked him why it didn't do what I thought it did. He frowned a bit and made some interested "mmm" noises, but ultimately agreed that he didn't know either. He took it away for further analysis. I never heard from him again.

There are two notable points here, which between them mean that the Wormhole Water Wheel has done its job, at least as a personal thought-experiment. Firstly: though I still don't know exactly what's wrong with it, it doesn't immediately look stupid to people who know a lot more about physics than I do, which is more than you can say for most perpetual motion machines. Secondly: it's raised questions in my own mind about the very nature of "stupid", and the way sentimentality - or, if you prefer, basic human need - influences our sense of speculation even when we think we're being wholly scientific. More than once while I was touting my impossible machine, I was left with the sense that the explanations as it Why It Didn't Work were based on the assumption that It Can't Possibly Work, even that the universe required safety protocols to ensure its failure... meaning, they weren't exactly explanations.

A third and incidental point is that the diagram would make a really nice T-shirt.

As adults, the contempt we feel for perpetual motion is as instinctive as our childhood belief that it must surely be possible. Often, such designs have been the symbol of absurd, irrational folly: I particularly like their status in Vonnegut's Hocus Pocus, his almost dinosaur-like description of them as the fossils of doomed ambition. Yet it takes an above-average understanding of physics to spot the hitch in the Wormhole Water Wheel, whatever the f*** it is. The very concept requires wormhole engineering as well as conventional Newtonian physics. Might we not at least speculate, then, that some even more exotic and unlikely combination of not-impossible elements might do exactly what the Water Wheel is intended to do? Ultimately, the Laws of Thermodynamics are considered unbreakable for two principle reasons. One is that no observation has ever been made which contradicts them, although this is possibly the most contentious area it's possible for a human being to enter. (Which is to say, the question "when has something ever come out of nothing?" could well be answered with the question "what are you currently standing in?". It's not unreasonable to suggest that "universe" and "a breach of the Laws of Thermodynamics" are synonymous... not unreasonable, but unprovable, at least for now.)

The second reason has less to do with observation than with history. Culturally, we need entropy: without it, we become children again. This is why, like the offspring of an abusive parent, we're inclined to defend it even though we secretly want it to go away and stop hurting us. It's not that we have a death-wish, it's just that our awareness of our own ultimate doom is what stops us behaving as if we can expect the Rapture at any moment. This doesn't mean we should consider its inviolability to be "true", nor should we deny the possibility that one day a Wormhole Water Wheel 2.0 will actually turn out to be workable, if only as a theoretical possibility.

Then again, I would say that. Because I don't want to die. And because I still find it perfectly acceptable - this time for reasons that are political as much as historical, or at least grounded in a sense of human creativity and human compassion - that there might be an Omega Point waiting for us at the end of time, a light at the end of a near-total darkness. A light of our own making.

None of which has very much to do with Doctor Who, at least not directly. Unless I'm a splinter of a Jagaroth whose future incarnation is trying to push you juuust a little bit further.

September 9, 2012

It's...

Lawrence Miles,

c/o The Office,

Castle Way,

Hanworth Park,

TW13 7QG.

Not where I live, but send a letter / summons there and it'll get to me. If you want to be extra-childish about it, you can also add:

England,

Europe.

Earth,

The Solar System,

The Milky Way (Mutters' Spiral),

The Universe.

September 5, 2012

The History of the History of "The Daleks" (in Graphs)

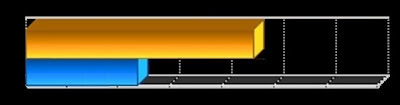

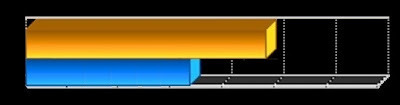

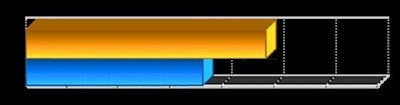

Early 1980s. At this point, of course, Ian Levine is barely-known beyond a very exclusive circle of fandom. Yet Peter Haining's Doctor Who: A Celebration tells us that "The Daleks" is still in the archive, unlike "The Time Meddler" or "Tomb of the Cybermen" or bits of "The Invasion". Whoever saved it from being deleted, hooray! We love you.

Early 1980s. At this point, of course, Ian Levine is barely-known beyond a very exclusive circle of fandom. Yet Peter Haining's Doctor Who: A Celebration tells us that "The Daleks" is still in the archive, unlike "The Time Meddler" or "Tomb of the Cybermen" or bits of "The Invasion". Whoever saved it from being deleted, hooray! We love you. Late 1980s. Typical '80s grimness sets in as "The Daleks" is released on video, and those who'd read about it in Doctor Who Weekly discover that it's not necessarily a retro-rollercoaster just because it's where the Daleks came from. At the same time, Ian Levine pushes John Nathan-Turner towards "Attack of the Cybermen" and the series towards self-destruction. But...!

Late 1980s. Typical '80s grimness sets in as "The Daleks" is released on video, and those who'd read about it in Doctor Who Weekly discover that it's not necessarily a retro-rollercoaster just because it's where the Daleks came from. At the same time, Ian Levine pushes John Nathan-Turner towards "Attack of the Cybermen" and the series towards self-destruction. But...! Early 1990s. ...the reputation of "The Daleks" is redeemed, as '70s kids who grew up with Doctor Who come of age and realise that despite the script, it's a brilliant piece of '60s design and experimental television. Its environments and radiophonics are justly praised. Sadly, the same '70s kids also see Ian Levine on TV for the first time and wonder if this weirdly aggressive, distinctly un-Doctorish man is really representing them properly. None of which is helped by rumours that he had "The Time Meddler", "Tomb of the Cybermen", and the missing bits of "The Invasion" all along.

Early 1990s. ...the reputation of "The Daleks" is redeemed, as '70s kids who grew up with Doctor Who come of age and realise that despite the script, it's a brilliant piece of '60s design and experimental television. Its environments and radiophonics are justly praised. Sadly, the same '70s kids also see Ian Levine on TV for the first time and wonder if this weirdly aggressive, distinctly un-Doctorish man is really representing them properly. None of which is helped by rumours that he had "The Time Meddler", "Tomb of the Cybermen", and the missing bits of "The Invasion" all along. Late 1990s. Admiration for "The Daleks" grows, despite gits who want all sci-fi on television to be like Babylon-5 and/or Neil Gaiman comics. The internet is invented, giving Ian Levine increasing opportunities to be "frank" with people. The true horror of the twenty-first century should've been obvious at about this point.

Late 1990s. Admiration for "The Daleks" grows, despite gits who want all sci-fi on television to be like Babylon-5 and/or Neil Gaiman comics. The internet is invented, giving Ian Levine increasing opportunities to be "frank" with people. The true horror of the twenty-first century should've been obvious at about this point. 2000s. Faith's argument in the now-popular Buffy the Vampire Slayer ("I've saved lives, so I can be an absolute cow-bag and do anything I want") strikes a terrible chord with those still trying to defend Ian Levine because of "The Daleks". The new series throws fandom into a confusion that distracts from both Serial B itself (despite a well-deserved screening on BBC4) and the increasing public vileness of the man responsible for its survival (this graph amended to remove the subject's severe but arguably one-off vileness to its compiler, although really).

2000s. Faith's argument in the now-popular Buffy the Vampire Slayer ("I've saved lives, so I can be an absolute cow-bag and do anything I want") strikes a terrible chord with those still trying to defend Ian Levine because of "The Daleks". The new series throws fandom into a confusion that distracts from both Serial B itself (despite a well-deserved screening on BBC4) and the increasing public vileness of the man responsible for its survival (this graph amended to remove the subject's severe but arguably one-off vileness to its compiler, although really). Modern era. Irony strikes, like that final wafer-thin mint with its razor-sharp edge. Ian Levine, a man now seen as so utterly monstrous that even Gary Barlow can't be nice about him, supports the series on the grounds that (a) some adolescents think it's cool, (b) the writer of "Love & Monsters" has gone away, and (c) it's full of old stuff buffed up a bit and taken out of context. You know, sort of like "Attack of the Cybermen", only with more personal schtick that girls might go for. The parallel facts, that the new chief writer (a) claimed to hate all science-fiction before 2005, (b) has stated only two Doctor Who stories to be any good before his own arrival, and (c) called Ian Levine "that c***", are overlooked by many. Including Ian Levine, amusingly. Meanwhile, "The Daleks" becomes irrelevant, as anything that doesn't look like a CGI action-movie is officially designated saa-aad. Ian Levine himself is too busy screaming at people on newsgroups to note the horrible sense of tragedy, occasionally even libelling them by claiming they're hoarding "lost" episodes, ironic given that he's so often been accused of keeping back the missing bits of "The Invasion".

Modern era. Irony strikes, like that final wafer-thin mint with its razor-sharp edge. Ian Levine, a man now seen as so utterly monstrous that even Gary Barlow can't be nice about him, supports the series on the grounds that (a) some adolescents think it's cool, (b) the writer of "Love & Monsters" has gone away, and (c) it's full of old stuff buffed up a bit and taken out of context. You know, sort of like "Attack of the Cybermen", only with more personal schtick that girls might go for. The parallel facts, that the new chief writer (a) claimed to hate all science-fiction before 2005, (b) has stated only two Doctor Who stories to be any good before his own arrival, and (c) called Ian Levine "that c***", are overlooked by many. Including Ian Levine, amusingly. Meanwhile, "The Daleks" becomes irrelevant, as anything that doesn't look like a CGI action-movie is officially designated saa-aad. Ian Levine himself is too busy screaming at people on newsgroups to note the horrible sense of tragedy, occasionally even libelling them by claiming they're hoarding "lost" episodes, ironic given that he's so often been accused of keeping back the missing bits of "The Invasion".If someone who knew the future pointed out a child to you, and told you that child would grow up totally horrid... to be a joyless monomaniac who'd bully, cajole, and spoil the experiences of everyone who loved the same thing he claimed to love, despite his humourless contempt for all its most basic principles... to stereotype you and most of your friends as the kind of violently obsessive, bloody-minded eejit that society always feared you were, to the extent of appearing on national telly and threatening to personally murder whoever lied about having episode four of "The Tenth Planet"... would you then do anything possible to prevent that child becoming like Ian Levine? Yes. Yes, I agree, I would too. Even if it meant making sure he never saw Doctor Who, ever.

And as the blue bar finally ticks over the yellow, even at the cost of "The Daleks". Nobody should ever feel compelled to be that grateful.

Lawrence Miles's Blog

- Lawrence Miles's profile

- 58 followers