Nancy E. Blanton's Blog, page 4

January 17, 2017

Tracking the Prince: Baltimore

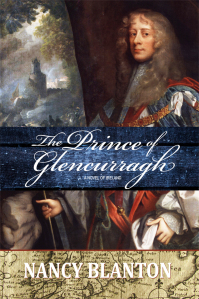

Part 13 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

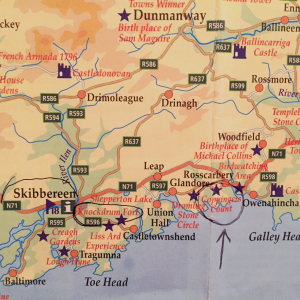

From Skibbereen in County Cork, a 15-minute drive southwest along the scenic R595 will bring you to the town of Baltimore. On the 17th century Down Survey map, Baltimore sits on the tip of a peninsula reaching toward the sea—a perfect location for fishing, boating and a bucolic agrarian lifestyle.

[image error]

In the early 17th century, it was an English settlement pursuing exactly such industry:

“In Southwest Munster, where planters both introduced inshore ‘seine’ netting and invested considerable sums in shore-based facilities for salting and barreling the catch, the export of pilchards rose significantly, at least in the 1620s and early 1630s. The industry was characterized by small-scale plantation-type development, and the trade, which was based on Kinsale, Brookhaven, Baltimore, Bantry, and Berehaven, was dominated by English and continental shipping.”

~ F.X. Martin, F.J. Byrne, A New History of Ireland: Early Modern Ireland, 1534-1691. Oxford Press, 1987.

On the same map, just above Baltimore is a notation for Rathmore, meaning large fort. This is the name I used for the Earl of Barrymore’s fictitious coastal castle in my book, The Prince of Glencurragh. It is to this castle that the book’s main characters are going, so that Barrymore can take them under his wing and negotiate a suitable marriage settlement for Faolán Burke and Vivienne FitzGerald. Today, a bed and breakfast by that name offers a gorgeous hilltop view at the mouth of the River Ilen.

[image error]

On a more recent map, you might see Old Court, a site at which I believed there was an ancient castle. I’d hoped to explore it, because this is where I’d imagined Barrymore’s castle would be located. If you go there today you’ll see a boat building and storage business, but it is indeed set among the ruins of a castle or fort, and a stone window still looks out over the water. We found it on a cool, rainy day in June, and so instead of ancient stones beneath our shoes we had a bit of mud that only served to make the experience its most authentic.

[image error]

[image error]

American readers will recognize the name Baltimore and maybe even Old Court. The City of Baltimore, founded in 1729 in the state of Maryland, started as and English colony in 1661, displacing the Piscataway tribe of Algonquians who had inhabited the lands for centuries. The city was most likely named for Lord Baltimore of the Irish House of Lords, Cecil Calvert, and his family’s Baltimore Manor in County Longford. Maryland was considered a safe haven for Irish Catholics hoping to escape religious persecution, and Calvert had obtained permission from the king to establish the colony.

This Baltimore has enjoyed a high percentage of Irish in its population because it drew a large number of Irish escaping Ireland’s famine of 1845-1853. They settled in southwest Baltimore and found work on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Today, on the Baltimore Metro Subway, you can catch a ride to Old Court Station on Old Court Road in Lochearn, Maryland.

But the Ireland Baltimore has a much more troubled history. In my last post I mentioned that the town of Skibbereen gained population and importance when settlers moved inland from Baltimore to escape Algerian pirates. A terrible raid in 1631 devastated Baltimore, as described in detail by Des Ekin in his book, The Stolen Village.[image error]

The site of Baltimore had been purposely chosen for an English settlement because of its remoteness, allowing greater religious freedom. It also had a reputation for smuggling, especially when it was in the hands of the O’Driscoll clan.

“In would come fine wine and brandies, silks and spices, tobacco and salt. Out would go wool, linen, leather goods…and the occasional fugitive fleeing the hangman’s noose.”

~ Des Ekin

But such remoteness also had its vulnerability, and on a dark June night of that year, three ships arrived carrying Algerian pirates who stormed ashore, killing two of the town’s residents and capturing 107 men, women and children. These captives joined 17 French captives already aboard the ships, and then all were taken to Algiers to be sold as slaves. A French priest observed:

“It was a pitiful sight to see them put up for sale. For then wives were taken from husbands and children from their fathers. Then, I declare, they sold on the one hand the husbands, on the other the wives, ripping their daughters from their arms, leaving them no hope of ever seeing each other again…”

~ Father Pierre Dan

Most of these poor souls were never seen again, because the ransoms were too high, and though King Charles I was petitioned for relief, his councilmen advised against paying, stating that it would only encourage the pirates. And to make matters worse, rumors circulated that the town had been set up for the raid by Sir Walter Coppinger, who wanted the settlers removed so that he might have the land and the lucrative pilchard business for his own (for more about this see my post, Coppinger’s Court).

The terrible event remains a stain on Baltimore’s past, but the town has revived as a summer haven for fishing, swimming and sailing, and as a base for exploring Cape Clear, Sherkin Island and Lough Hyne, Ireland’s first marine nature reserve. And you can rent a 4-bedroom cottage called Old Court at Skibbereen.

[image error]

Thanks to Eddie and Teresa MacEoin, Trinity College Down Survey, Des Ekin’s The Stolen Village, Irish Central News, Irish Railroad Workers Museum, Old Court Boats, and Wikipedia. Except for the map, all images belong to the author.

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle

Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt

Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle

Part 6 – Bandon, Kilcolmen

Part 7 – Timoleague Friary

Part 8 – Castle Freke, Rathbarry, Red Strand

Part 9 – Coppinger’s Court

Part 10 – Drombeg and Knockdrum

Part 11 – Liss Ard, Lough Abisdealy

Part 12 – Skibbereen

[image error]An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

OR, try this universal link for your favorite ebook retailer: books2read.com

Learn more and sign up for updates via my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

January 9, 2017

Tracking the Prince: Skibbereen

Part 12 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

Of all sites visited along this journey with The Prince of Glencurragh, the one I’ve feared to write about most is this, the town of Skibbereen. How would I ever do justice to a town so sunny-gold in my memory, and yet tarnished gray by events in history? Refuge for settlers, home for fishermen, famed as of one of the worst affected by The Great Famine, Skibbereen survives and thrives in its colorful, splendid way. Each time I visit, it looks like some familiar place I’ve never seen.

[image error]

[image error]In the far southwest corner of County Cork, Skibbereen lies where the N71 meets the River Ilen (pronounced like “island”), just a few miles northeast of Baltimore. In fact, Skibbereen began to gain importance after Algerian pirates raided Baltimore in 1631, and survivors moved upstream for safety. Before that, Skebreen (as it is spelled on 17th century maps) was mostly overlooked by cartographers of the time, though it was at the center of three castles held by the powerful MacCarthy clan.

The fate of the castles is not clear, though they may have been lost during the Nine Years’ War against English rule in Ireland, or after the Battle of Kinsale. Today, north of the river and west of the town center is a residential area known as Glencurragh, with nice family houses along Glencurragh Road. In my book, this is where I sited Faolán Burke’s home, among the ruins of his father’s Castle Glencurragh. It is always sunny there, in my mind, with only the occasional soft shower at the most appropriate times to keep the lush foliage a proper shade of green.

Which is not to say The Prince knows only happiness. His adventures are fraught with danger, frustration, and heavy rain. But home is home, and this is where his dreams are rooted, and where he hopes to raise his family. I think readers will like it there as well.

Originally I imagined the castle to be north and east of the Ilen Street Bridge near the present-day site of an old railway station, but my friend Eddie explained that the ground there was too marshy to support a castle. It’s fiction, you might say, so who cares if it is too marshy in reality? Eddie and I cared, wanting the book to be as real as possible. You never know when actual events might come into play in historical fiction. If the site had come under attack, the marshy ground would have played a role.

Glencurragh was better suited and would have been the choice of actual builders, and the name itself inspired me. Coming from the Irish meaning ‘a place for boats,’ I imagined a mullioned window overlooking the commerce along the river.

[image error]

The beautiful River Ilen at Skibbereen, County Cork

Coming south to us from the Mullaghmesha Mountain, she lay in bronze repose with her misty veil close at her surface. She was the very river who nourished every fox and sparrow from above Bantry and all the way out to sea at Baltimore. At Skebreen she abruptly turned west as if she’d simply changed her mind, and then south again as if to wrap a gentle arm about us. Sometimes flowing narrow and peaceful, she was our meandering ribbon of sweet dark nectar yielding trout in the spring and salmon in summer. With the winter rains she swelled at her seams, as anxious and irritable as a new mother; and, yes, wasn’t the earth at her flanks the most fertile?

~ Description of the River Ilen from my novel Sharavogue

Mostly a small and quiet town, in the mid-17th century Skibbereen had fewer than 150 residents as counted by the census. By 1841, that number had slowly climbed to 5,000. But soon that would change.

The Great Irish Famine wiped out about 8.5 million people in Ireland between 1846 and 1851, and more than a million more people emigrated for a chance of survival. Skibbereen was among the areas hardest hit.

“The average population loss in the Poor Law Unions of Cork was 24.2% but Skibbereen Poor Law Union came in with the highest loss in all of Cork, losing 36.1% of its people. It is therefore not surprising that Skibbereen became synonymous with The Great Famine, featuring prominently in its historiography.”

~ Tim Kearney, The Great Famine and Skibbereen

The nightmarish stories of suffering and death are too numerous to report here. Kearney’s article is a fine detailed overview, and I also highly recommend The Great Hunger by Cecil Woodham-Smith. This book brought me to tears and fury. The good news is that the situation in Skibbereen also attracted numerous writers, journalists and historians, and because of the resulting coverage the town “played a pivotal role” in affecting relief efforts.

[image error]

Skibbereen town center with The Maid of Erin memorial

There are several famine memorials in Skibbereen, and at the town center The Maid of Erin commemorates those who suffered in the famine as well as the heroes who fought for freedom in the Irish rebellions. Another memorial is inscribed with lyrics from the song, Dear Old Skibbereen, that Eddie taught me years ago and I’ve never forgotten:

Oh son, I loved my native land, with energy and pride / Til a blight came over all my crops, my sheep and cattle died / My rent and taxes were to pay, I could not them redeem / And that’s the cruel reason why I left old Skibbereen.

[image error]

A used book store I found, loved, and hope is still there.

Thankfully, my memories are of happier times. When I first visited Skibbereen and stayed with Eddie’s family, I remember walking to the local hotel for dinner to celebrate his mother’s birthday: the raucous bantering of six brothers and sisters, everyone full of excitement and cheer, Mrs. MacEoin’s coy smile. Then the breakfast in the warm kitchen, the laundry drying on lines across the high ceiling above us; the squabbling over the tin of fresh scones; and quiet Mr. MacEoin escaping the noise and frenzy by tending his beehives in the back yard.

Sometimes I could kick myself for not taking more pictures and recording every detail in my journal, but frankly it was all too much fun to write.

Thanks to Eddie and Teresa MacEoin and family; Dear Old Skibbereen; Journal, Skibbereen District and Historical Society, Vol. 7; and http://www.technogypsie.com. Images of the town belong to author and are several years old.

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle

Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt

Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle

Part 6 – Bandon, Kilcolmen

Part 7 – Timoleague Friary

Part 8 – Castle Freke, Rathbarry, Red Strand

Part 9 – Coppinger’s Court

Part 10 – Drombeg and Knockdrum

Part 11 – Liss Ard, Lough Abisdealy

[image error]An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

OR, try this universal link for your favorite ebook retailer: books2read.com

Learn more and sign up for updates via my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

December 20, 2016

Tracking the Prince: Liss Ard, Lough Abisdealy

Part 11 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

[image error]Just west of Castletownshend and less than four miles from Skibbereen, there once was a ring fort high on a hill. All but gone now, the place still bears the name, Liss Ard, meaning “high fort.” Turning off the main road, instead of discovering a ruin you’ll come to an attractive high-end resort near the tranquil waters of Lough Abisdealy.

Here, along its lush banks, I found the very tree I needed for an exciting scene in The Prince of Glencurragh. It is here that protagonist Faolán Burke sets his trap for the bad guy who stalks him, Geoffrey Eames. Eames ends up tied to the tree, his feet at the water’s edge, and is left to his own devices to get himself free. Appropriate, perhaps, because by at least one source Lough Abisdealy means “lake of the monster.”

[image error]

A lakeside tree for Mr. Eames

[image error]On a map, the shape of Abisdealy looks to me like a giant sperm whale with its tail flipped up. While the lake is a favorite spot for some who fish for pike or carp, it has also produced sightings of another kind of monster, the conger or horse eel—giant eels in the likeness of the Loch Ness monster, as described in another location:

When the normally gushing waters linking lakes and rivers became reduced to a pathetic drizzle a large horse-eel was discovered lodged beneath a bridge by Ballynahinch Castle. The beast was described as thirty feet long and “as thick as a horse.” A carpenter was assigned to produce a spear capable of slaying the great creature but before the plan could be carried through rains arrived to wash the fortunate beast free.

~ Dale Drinnon, Frontiers of Zoology

And in 1914 at Lough Abisdealy, author Edith Somerville reported sighting “a long black creature propelling itself rapidly across the lake. Its flat head, on a long neck, was held high, two great loops of its length buckled in and out of the water as it progressed.”

I saw no snakes, eels or monsters when I visited the lake, but what I did see was a visual feast of trees, their forms twisted, curved and swayed as if they were dancing.

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

[image error]

Entrance to the Sky Garden

If you have an extra €7,500,000 handy you can pick up the estate for your very own. The real estate sales listing describes the “truly remarkable” 163-acre residential estate as a pleasure complex with Victorian mansion (6 bedrooms), Mews House (9 bedrooms) and Lake Lodge (10 bedrooms), plus tennis court, private 40-acre lake, and the Irish Sky Garden designed by artist James Turrell where you might “contemplate the ever-changing sky design.”

While it is not from the 17th century when my novel is set, the location does have some history to it:

“The Mansion house was built by the O’Donovan Chieftain of the O’Donovan Clan circa 1850 and a summer house, a moderately large house, was added to the estate circa 1870. This Summer House now referred to as the Lake Lodge.”

From the lake, the characters in The Prince… are just a few more miles from their destination, Rathmore Castle at Baltimore, and an important meeting with the Earl of Barrymore.

Thanks to Eddie and Teresa MacEoin, Dick Raynor, Exploring West Cork by Jack Roberts, Dale Drinnon and the Frontiers of Zoology, Liss Ard Estate.

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle

Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt

Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle

Part 6 – Bandon, Kilcolmen

Part 7 – Timoleague Friary

Part 8 – Castle Freke, Rathbarry, Red Strand

Part 9 – Coppinger’s Court

Part 10 – Drombeg and Knockdrum

[image error]An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

OR, try this universal link for your favorite ebook retailer: books2read.com

Learn more and sign up for updates via my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

December 12, 2016

Tracking the Prince: Drombeg and Knockdrum

Part 10 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

The hills and bluffs of southwest Cork are not only beautiful, but also magical. It seems at every turn you may find something ancient to fascinate you. Just a short distance from Coppinger’s Court along the Glandore Road, we parked on a narrow dirt road to climb the grassy hill to Drombeg Stone Circle.

[image error]This place had interested me from afar. I didn’t intend to use a stone circle in The Prince of Glencurragh, but this one happened to sit along the travel trajectory and, despite several earlier trips to Ireland, I had never actually visited a stone circle.

I wonder if everyone who visits them secretly hopes to have some kind of mystical experience? Perhaps not of “Outlander” proportions where the novel’s heroine is transported back 200 years, but at least some kind of physical or spiritual sensation. I wonder how many actually do? For me there was just the simple thrill of being there, touching something so old and at one time sacred, and imagining the people upon whose footsteps I walked.

[image error]Also known as “The Druid’s Altar,” archaeologists say this 17-stone circle was in use 1100 to 800 BC. The stones slope toward its famous recumbent stone that seems to align with the winter solstice. Depressions and a cooking area (fulacht fiadh) may have been in use until the 5th century AD.

But I’ve got news for archaeologists: visitors to this site are using it still, based on the tokens and offerings they leave behind. Countless prayers must have been uttered here, and it feels almost intimate, the circle small and cloaked within a soft Irish mist. We were there in June, but had we been there at sunset in December, I’m sure we would have heard the spirits singing…

[image error]

[image error]From there we passed Glandore where we would later eat a spectacular dinner at a waterfront restaurant, and Union Hall where I saw the view of the harbor that has enchanted people for ages (and is captured so creatively by the artists in the book, The Old Pier, Union Hall, by Paul and Aileen Finucane).

But my destination now was Knockdrum Fort, a few miles farther west. Knockdrum is one of Ireland’s many Iron Age stone ring forts, but this one was reconstructed in the 19th century. It has massive stone walls four to five feet high, arranged in a ring to provide protection as well as a 360 view of the surrounding area. Historians say that while it looks like a defensive fort, its purpose may have been sacred instead. The standing boulder just inside the entrance is inscribed with a large cross.

[image error]

Eddie stands within the central house foundation at Knockdrum, within stone outer walls

[image error]Through my research I learned the fort had a souterrain with three chambers cut from solid stone, one having a fireplace and flue. One source said the underground passage went all the way down to the sea.

If this was so, I would indeed plan to use this site for a scene in my book. On paper it seemed the perfect location for a pursuit, a setup, a trap, and then a wily escape through the souterrain. And this is why actual site inspection is so important for an author.

Especially for historical fiction, readers want to learn something of the history as they read, and so, while characters and their actions can be fictional, readers expect a high level of accuracy in locations and historical events. I could not portray the location truthfully and still use it in the story because it was set high on a promontory, creating an unnecessary and unrealistic difficulty for the characters. And, if the souterrain was used for the escape route, it would have been quite a long way almost straight down to the sea, with the only advantage being if you had a seaworthy vessel waiting at the bottom.

[image error]

View over Knockdrum’s outer wall to the sea: it’s a long way down!

The souterrain was gated off so I could not see inside it, but I had seen enough to know that, while a remarkable site to explore, it would not serve the story well. Perhaps it will find a home in another story one day. The fort’s impressive size and appearance, and the view from all sides, is unforgettable.

Looking northeast of the site as we left it, we saw the “Five Fingers,” or rather three of them. These are megalithic stones jutting from a hill, looking like the skeletal fingers of a giant reaching for the sky—a high five for our explorations that day.

But I still needed a location for that scene in my story. And for this, the Liss Ard would serve quite nicely; coming up next week.

Thanks to Megalithic Ireland, Exploring West Cork by Jack Roberts, Irish Archaeology, abandonedireland.com, Irish Archaeology, The Old Pier, Union Hall, by Paul and Aileen Finucane.

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle

Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt

Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle

Part 6 – Bandon, Kilcolmen

Part 7 – Timoleague Friary

Part 8 – Castle Freke, Rathbarry, Red Strand

Part 9 – Coppinger’s Court

[image error] An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

Learn more and sign up for my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

December 6, 2016

Tracking the Prince: Coppinger’s Court

Part 9 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

I first discovered Coppinger’s Court as a notation on a West Cork tour map. I was seeking a route that my characters in The Prince of Glencurragh would travel from Timoleague to Clonakilty and west along the coast to Baltimore. I wondered if it might become a stopping place along their way, but instead the manor house was so dramatic it inspired another scene altogether.

Coppinger’s Court, also known as Ballyvireen, is located along the Glandore road about two miles west of Rosscarbery. Described as a fortified manor house in the Elizabethan style, the structure has three wings off of a central court, creating nine gables, and each exterior wall has large mullioned windows that would have ensured good natural light.

Coppinger’s Court, also known as Ballyvireen, is located along the Glandore road about two miles west of Rosscarbery. Described as a fortified manor house in the Elizabethan style, the structure has three wings off of a central court, creating nine gables, and each exterior wall has large mullioned windows that would have ensured good natural light.

Considered a place of opulence in its day, the house was said to have been “the finest house ever built in West Cork,” and is credited with having “a chimney for every month, a door for every week, and a window for every day of the year.”

With a description like that, I had to see it. And I already knew it would become the model for the fictitious Rathmore House, the seaside home of the Earl of Barrymore located near the town of Baltimore.

With a description like that, I had to see it. And I already knew it would become the model for the fictitious Rathmore House, the seaside home of the Earl of Barrymore located near the town of Baltimore.

In The Prince of Glencurragh, Faolán Burke, his abducted/intended bride, and accomplices are rushing across Ireland’s south coast toward Baltimore. There they must meet the Earl of Barrymore who has promised to negotiate the marriage settlement. The story takes place in 1634, just three years after the town of Baltimore has been devastated by an attack and raid by Algerian pirates.

This attack was a real and violent event. Most of the town’s residents were abducted, a small number of them were ransomed, and the rest were killed, sold or used as slaves. The few survivors moved inland to Skibbereen for safety. I placed the Earl of Barrymore’s house, Rathmore, at a cove between the two settlements.

And I soon discovered a close and perhaps sinister connection between Coppinger’s Court and the town of Baltimore, centered on the builder of the great house, Sir Walter Coppinger. Sir Walter took pride in his Viking bloodline, and descended from a mercantile family well known in Cork for centuries:

And I soon discovered a close and perhaps sinister connection between Coppinger’s Court and the town of Baltimore, centered on the builder of the great house, Sir Walter Coppinger. Sir Walter took pride in his Viking bloodline, and descended from a mercantile family well known in Cork for centuries:

“In 1319 Stephen Coppinger was mayor of the city, and several of his descendants held this position as well as becoming bailiffs and sheriffs of Cork. The Coppingers remained Roman Catholic and could therefore only afford to build a relatively modest residence at Glenville, of two storeys and five bays fronted by a semi-circular courtyard with a gate at either end.”

~ The Irish Aesthete

Sir Walter, however, was far from modest. He was a businessman, lawyer, landowner, and moneylender, who acquired many of his properties from borrowers who defaulted on their loans. Several sources support his reputation for ruthlessness, and perhaps unscrupulousness.

“Sir Walter Coppinger is remembered, probably wrongly, as an awful despot who lorded it over the district, hanging anyone who disagreed with him from a gallows on a gable end of the Court.”

~ Abandoned Ireland

Sir Walter wished to own Baltimore for its castle and properties, and lucrative pilchard industry. He was involved in legal battles for ownership, but in 1610 he and other claimants agreed to lease the town to English settlers for 21 years. By the end of the lease, Coppinger had brought a case before the king’s Star Chamber, claiming the town as his own and asking to evict the English settlers. But he grew frustrated when the chamber members were reluctant to decide the case, and reluctant to evict prosperous families who had made improvements to the properties. And then came the pirates.

“There is no concrete evidence that Coppinger had any role in organising the Algerine raid of 1631. But it conveniently removed the only obstacle to his total control of Baltimore.”

~ Des Ekin, The Stolen Village

If he was responsible, it seems Karma won in the end. Coppinger was not to benefit from his long-coveted Baltimore. The town’s vast annual pilchard run suddenly disappeared, and by 1636 he had leased out his new castle and village. Sir Walter died in 1639. Then came the great Irish rebellion of 1641. Coppinger’s Court was ransacked and burned, and then confiscated by Oliver Cromwell in 1644. By 1690 after years of disuse, the great house was on its way to becoming another beautiful ruin.

Friendly greeter at the Coppinger’s Court gate

Thanks to The Irish Aesthete, Exploring West Cork by Jack Roberts, The Stolen Village by Des Ekin, abandonedireland.com,

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle

Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt

Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle

Part 6 – Bandon, Kilcolmen

Part 7 – Timoleague Friary

Part 8 – Castle Freke, Rathbarry, Red Strand

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

Learn more and sign up for my newsletter at nancyblanton.com

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

November 28, 2016

Tracking the Prince: Rathbarry and the Red Strand

Part 8 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

Sometimes, though sand and water wash away the past, research and imagination still can resurrect it.

Castlefreke

From Timoleague, Clonakilty is nearly a straight shot west along the R600. Heading south from there are rolling hills, green bluffs and marshy expanses leading toward Dunnycove Bay. On most driving and tour maps you’ll see a notation for Castlefreke.

Built by Randall Oge Barry in the 15th century, the fort was lost to the English after the Battle of Kinsale, was besieged and later burned during the Rebellion of 1641. A tower house was built on the site in 1780, which was remodeled in 1820, burned down in 1910, and at the time of my visit it was being remodeled as an event venue. However we did not visit Castlefreke itself, because it was not my destination. Instead, I wished to see Rathbarry Castle, the Red Strand, and just a little farther west, Coppinger’s Court.

Wall of old Rathbarry

Featuring characters from the Barry family in The Prince of Glencurragh, I sought locations where they might have met or slept. I was to find little remaining of the castle, but enough to stir my imagination, and even more so, the illuminate larger forces that had been in play in the region.

Thanks to my friends Eddie and Teresa, who introduced me to their friend Pat Hogan, I was able to visit and learn much about Rathbarry, and it became a landmark in the book, near the cottage of the mysterious healer Pol-Liam.

The castle Rathbarry existed on the site of what is now Castlefreke, bearing the family name of Freke for the current owners. Far out on the roadway, the gateposts marking the entrance to the castle grounds with their large spherical tops were said to be true remnants of the 17th century. Just one wall of the ancient stables and carriage house remained, and a new stable house had been built within it remodeled as a private residence. We were treated to a peek inside this structure to get a feel for what home life was like there.

The castle Rathbarry existed on the site of what is now Castlefreke, bearing the family name of Freke for the current owners. Far out on the roadway, the gateposts marking the entrance to the castle grounds with their large spherical tops were said to be true remnants of the 17th century. Just one wall of the ancient stables and carriage house remained, and a new stable house had been built within it remodeled as a private residence. We were treated to a peek inside this structure to get a feel for what home life was like there.

From the upper wall of the ruin, crumbling stone stairs led down to an ancient watergate, a stone passage leading directly from the castle to the water, where boats would have come to deliver food and supplies. But, except for a small, enclosed pond, there was no water. From the top of the steps I could see the bay, maybe half a mile distant. How, I wondered, could the castle have been served from such a distance?

From the upper wall of the ruin, crumbling stone stairs led down to an ancient watergate, a stone passage leading directly from the castle to the water, where boats would have come to deliver food and supplies. But, except for a small, enclosed pond, there was no water. From the top of the steps I could see the bay, maybe half a mile distant. How, I wondered, could the castle have been served from such a distance?

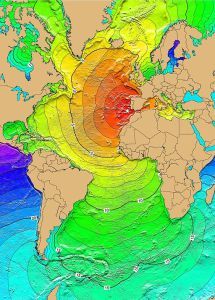

Estimated distance and travel times for Lisbon tsunami (NOAA, public domain)

As Mr. Hogan reminded me, the landscape had changed dramatically since the 17th century, and events at the global level could have affected Ireland’s coastlines. In fact, in 1755 the Great Lisbon Earthquake and tsunami are believed to have done so. Considered one of the deadliest earthquakes in history, it is estimated to have hit the 8.5 to 9.0 range on today’s scale of magnitude, killed thousands of people and nearly devastated Lisbon. The tsunami’s impact was far-reaching.

“Tsunamis as tall as 20 metres (66 ft) swept the coast of North Africa, and struck Martinique and Barbados across the Atlantic. A three-metre (ten-foot) tsunami hit Cornwall on the southern English coast. Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, was also hit, resulting in partial destruction of the “Spanish Arch” section of the city wall. At Kinsale, several vessels were whirled round in the harbor, and water poured into the marketplace.”

~ Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, 1830

Gigantic waves were reported as well in the West Indies and Brazil. Could these environmental events have shifted sands and reshaped Ireland’s coastline? Undoubtedly.

Gigantic waves were reported as well in the West Indies and Brazil. Could these environmental events have shifted sands and reshaped Ireland’s coastline? Undoubtedly.

Almost within view of Rathbarry was another site I wished to visit: the Red Strand. Also likely to have been altered by the tsunami, this sandy beach was called “red” because the sand contained fossilized sea creatures or “calcareous matter,” which was believed to have a healing effect and also promote fertility. As late as the 19th century the sand was being collected for use in fertilizing crops some 16 miles away.

The only red I saw during my visit was in the clumps of seaweed washed ashore; still, the strand fascinates, bounded on one side by stones, and on the other by bluffs and stream. The strand and the story behind it served my imagination for a deadly scene in the book.

Next time: Coppinger’s Court.

Thanks to: Library Ireland, Exploring West Cork by Jack Roberts, Castles.nl, Pat Hogan, Eddie McEoin, Wikipedia and other sources.

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle

Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt

Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle

Part 6 – Bandon/Kilcolman

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

November 21, 2016

Tracking the Prince: Timoleague

Part 7 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous post links below.

Driving south from Bandon on R602, you will arrive at the town of Timoleague in about 20 minutes, and see immediately the great landmark of Timoleague Friary. For the Prince of Glencurragh, traveling on horseback, at night and over rugged terrain, it would have taken at least three hours to reach this first stop on Faolán Burke’s path to destiny.

Driving south from Bandon on R602, you will arrive at the town of Timoleague in about 20 minutes, and see immediately the great landmark of Timoleague Friary. For the Prince of Glencurragh, traveling on horseback, at night and over rugged terrain, it would have taken at least three hours to reach this first stop on Faolán Burke’s path to destiny.

In the 17th century, local parishes were required to maintain their roads, especially in market towns. In 1634, a new act of Parliament allowed for a tax levy to cover the costs. But it would be decades before Ireland’s road systems were noted for improvements. A Scotsman traveling through Ireland in winter around 1619-1620 described his horse as “sinking to his girth” on boggy roads, his saddles and saddlebags destroyed.

Timoleague Franciscan friary would have provided a most welcome shelter to travelers, even it its ruined state. It remains a massive and impressive structure, the walls of the various rooms still intact so that you can recognize the floor plan and how each room was used. The roof is long gone, and some sources say that parts of the structure were carted away for use in other buildings.

Timoleague Franciscan friary would have provided a most welcome shelter to travelers, even it its ruined state. It remains a massive and impressive structure, the walls of the various rooms still intact so that you can recognize the floor plan and how each room was used. The roof is long gone, and some sources say that parts of the structure were carted away for use in other buildings.

From the mullioned window in the chorus, one would be hard-pressed to find a view more peaceful and contemplative. This is the spot where my heroine, Vivienne, considers her circumstances, having been abducted by three strange men, however benevolent they might have seemed. It’s the place where narrator Aengus recalls a treasured time with his father. And it is where he and Vivienne first realize a common bond.

From the mullioned window in the chorus, one would be hard-pressed to find a view more peaceful and contemplative. This is the spot where my heroine, Vivienne, considers her circumstances, having been abducted by three strange men, however benevolent they might have seemed. It’s the place where narrator Aengus recalls a treasured time with his father. And it is where he and Vivienne first realize a common bond.

Scenes in the book came alive for me as I entered each room and walked the same paths of monks and soldiers, and imagined conversations echoed in my mind.

Timoleague is an Anglicization of the Irish Tigh Molaige, meaning House of Malaga for St. Malaga who is believed to have first brought beekeeping to Ireland. Foundation of the friary is attributed to the McCarthys in the 13th century, and also to William de Barry and his wife Margery de Courcy in the 14th century. Unfortunately, its position along the beautiful River Argideen and overlooking Courtmacsherry Bay made it vulnerable to Algerian pirates who sometimes cruised Ireland’s coastline in search of hostages and plunder.

However, pirates may have seemed a minor threat compared the friary’s fate in the hands of the English. In King Henry VIII’s time, the structure was seized and as part of the Reformation the monks were dispersed. The monks returned in 1604, and then the English soldiers returned in 1612 to sack the buildings and smash all the stained glass windows. Then in 1642, English soldiers fighting the great Irish rebellion burned both the friary and town.

However, pirates may have seemed a minor threat compared the friary’s fate in the hands of the English. In King Henry VIII’s time, the structure was seized and as part of the Reformation the monks were dispersed. The monks returned in 1604, and then the English soldiers returned in 1612 to sack the buildings and smash all the stained glass windows. Then in 1642, English soldiers fighting the great Irish rebellion burned both the friary and town.

Many headstones dot the friary’s hillside, and large stone tombs in the nave are so ancient the chiseled inscriptions are no longer legible. Yet, the ruin is still an active cemetery for the local community.

Thanks to Timoleague Friary, Roaringwater Journal, Monastic Ireland. Photos belong to the author.

Series posts:

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle Part 6 – Bandon, Kilcolmen

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

See all of my books and other information at

November 14, 2016

Tracking the Prince: Bandon and Kilcolmen

Part 6 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous posts listed at the end.

Oliver Plunkett Street, photo by Brian Abbott, CC BY-SA 2.0 wikimedia commons

My research for The Prince of Glencurragh truly gained momentum when I visited Bandon in County Cork. Here I saw the place where my story began, and realized my reconnection with an old friend was the key that would allow the story to unfold.

Known as the gateway to West Cork, the city of Bandon lies 27 km (not quite 17 miles) west of Cork City. Established in 1604 as part of King James I’s Munster Plantation, it was a planned settlement English Protestants in Ireland. The famous stone bridge dates back at least to 1594, connecting people on either side of the Bandon River to facilitate trade. A timber bridge had existed even earlier, built by the O’Mahony (Oh-MAY-hon-ee) clan in 14th century.

When Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Cork, acquired the lease for all the properties of the town, he began a five-year project to enclose 27 acres within a wall nine feet thick and from 30 to 50 feet high in some places. On the heels of the Desmond Rebellions, this was intended to protect the peaceful settlers within against the wild Irish without.

Protection was needed against the unrest the settlement itself had created. Bandon lands had belonged to the O’Mahony and McCarthy clans, and the displacement left Irish families homeless and their sons without inheritance, sowing seeds for an even greater rebellion than the Desmonds could muster.

For the story in The Prince of Glencurragh, Bandon’s wall is critical, because certain local laws were enforced by a sheriff within the town’s walls, but did not extend beyond them. When the would-be “prince” Faolán Burke abducts his heiress from a rectory situated outside the town walls, technically he has broken no laws.

In preparation for my travels, my research uncovered a near-perfect model for this rectory, the Kilcolmen Rectory just east of where the walls of Bandon would have reached. To my surprise and delight, my dear friends and guides Eddie and Teresa actually live in Bandon (I had thought they still lived in Templemore).

I met Eddie when I was 19 or 20, visiting Ireland for a summer study program, and had the privilege of staying with his family in Skibbereen for a few days. We had not seen each other in decades, and so the reconnecting was gratifying and emotional.

Eddie knew of the rectory and was able to take me straight there. Though it is now a private home, Eddie chatted with the resident—she was leaning out of the upstairs bathroom window where she’d been bathing her children—while I looked about the house and grounds. We did not go inside, but Eddie sent me some interior photos he happened upon when the house went on the real estate market months later.

Eddie knew of the rectory and was able to take me straight there. Though it is now a private home, Eddie chatted with the resident—she was leaning out of the upstairs bathroom window where she’d been bathing her children—while I looked about the house and grounds. We did not go inside, but Eddie sent me some interior photos he happened upon when the house went on the real estate market months later.

This rectory is much larger and finer than the one I had imagined, but served quite well to give me an authentic feel for the place. The front door is opposite the stairs, and on either side are doorways to the parlor and the dining room. I loved the enormous windows of the place, and the high ceilings. The bedroom is where the character Vivienne would have pushed her bed beneath a window to wait for St. Agnes to reveal the image of the man she would marry. The road outside would have been a dirt carriage path instead of a nice, clean paved drive.

This rectory is much larger and finer than the one I had imagined, but served quite well to give me an authentic feel for the place. The front door is opposite the stairs, and on either side are doorways to the parlor and the dining room. I loved the enormous windows of the place, and the high ceilings. The bedroom is where the character Vivienne would have pushed her bed beneath a window to wait for St. Agnes to reveal the image of the man she would marry. The road outside would have been a dirt carriage path instead of a nice, clean paved drive.

Eddie later showed me that Bandon’s town walls are mostly invisible now but for some crumbling remnants. Still, the wall sets the town apart and Bandon is a member of the Irish Walled Towns Network.

Eddie later showed me that Bandon’s town walls are mostly invisible now but for some crumbling remnants. Still, the wall sets the town apart and Bandon is a member of the Irish Walled Towns Network.

Upon seeing these things, the story became real to me and I could tell it with sincerity. But the truth is I would never have found or seen the places I was looking for without Eddie and Teresa. It is one thing to look at a map and draw circles and lines, and yet another to actually find your way around a mostly unmarked and unfamiliar region. They took me everywhere I wanted to go, for they knew each place already, and even more than that, they had personal history with some of them, a love of exploration, and an often unspoken but clear reverence for the land and its history.

They showed me a ruin not on my list, but beautiful and fascinating: Castle Bernard. Where once there had been a medieval castle belonging to the O’Mahonys, in 1788 the first earl of Bandon, Francis Bernard, built a beautiful mansion with tall windows and soaring castellated towers.

By the time it was inhabited by the 4th earl, James Francis Bernard, a new and modern rising came from the IRA. In June 1921, while the earl hid in the cellar, IRA soldiers set fire to the castle and captured the earl as he tried to escape. Now mostly swallowed up by the woods and vines, the magnificence and inaccessibility of the ruin spur the imagination.

From Bandon we would travel for three spectacular days to uncover the rest of Faolán Burke’s trail.

As a side note, my friends in the Pacific Northwest might like to know that Bandon has a twin city agreement with Bandon, Oregon. In 1873, Lord George Bennet founded the city and named it after his hometown in Ireland. Bennet is known for introducing the lovely-flowering but highly troublesome gorse to the American landscape.

Thanks to: Irish Walled Town Network, Heritage Bridges of County Cork (Cork County Council), Castles.nl, Wikipedia and other sources.

Part 1 – Kanturk Castle

Part 2 – Rock of Cashel

Part 3 – Barryscourt

Part 4 – Ormonde Castle

Part 5 – Lismore Castle

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

November 2, 2016

The Prince Of Glencurragh: The Backstory

On October 22, the Florida Writers Association bestowed the coveted Royal Palm Literary Award on my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. This is an enormous honor and a great thrill. I worked harder on this book than anything before, loved the story and characters, and I’m gratified that the judges loved it, too: first place for historical fiction, and first runner up for book of the year across all genres in its category.

On October 22, the Florida Writers Association bestowed the coveted Royal Palm Literary Award on my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. This is an enormous honor and a great thrill. I worked harder on this book than anything before, loved the story and characters, and I’m gratified that the judges loved it, too: first place for historical fiction, and first runner up for book of the year across all genres in its category.

So here’s the backstory: why I wrote it, what it’s about, and some themes that I hope will come through for readers.

This book is actually the prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue (also a Royal Palm award winner in 2014). It is about that protagonist’s father, Faolán Burke. I had originally intended to write the sequel, but at the time several readers urged me to tell what had happened before, and how Elvy Burke came to be in her troubled situation. So I focused instead on 1634, the year Elvy was born, and found the time rich with change, struggle, and growing discontent that would lead to the great Irish rebellion of 1641.

About the title

The Prince refers to the protagonist in the story, Faolán Burke, who aspires to be a leader among his people, and to build the castle that was his father’s dream. The gentleman on the cover is not a prince; he was James Butler, the 12th Earl of Ormonde, and later the first Duke of Ormonde, who embodied all the princely attributes of his day – he is the ideal, what Faolán would hope to become.

National Portrait Gallery

Ormonde was one of the largest landholders in Ireland at the time, and land was power. He ascended to the earldom at just 24 years of age, when his grandfather died, because the first heir, James’s father, had been lost at sea. This ceremonial portrait was a great inspiration to me: I was fascinated by the pride and strength in his face, the long golden curls, and the magnificent robes. He was admired by almost everyone in his day; he was a statesman of his time.

Biographer C.V. Wedgwood describes James Butler as a “high-hearted” nobleman: “Handsome, intelligent and valiant, he was also to the very core of his being a man of honor: loyal, chivalrous and just.”

One little quirk you might notice on the cover, if you look at Ormonde’s right hand holding the lance. He appears to be missing a finger! In later portraits the finger exists, so this must be a mistake (or perhaps intentional) by the artist.

One little quirk you might notice on the cover, if you look at Ormonde’s right hand holding the lance. He appears to be missing a finger! In later portraits the finger exists, so this must be a mistake (or perhaps intentional) by the artist.

Glencurragh comes from a residential section of Skibbereen, a town in southwest County Cork (in the book I use the old spelling, Skebreen). When I visited there last year, my friend of many years helped me find the most likely place where my fictitious castle might have been located. Glencurragh means “a place for boats,” and the castle would’ve protected the commerce up and down the River Ilen. At one point in time there were three castles along the river at Skibbereen, but all have crumbled away.

It’s because of my affection for this friend and his family that both novels are set, at least in part, in their beautiful hometown, Skibbereen.

It’s because of my affection for this friend and his family that both novels are set, at least in part, in their beautiful hometown, Skibbereen.

So what’s the story about?

It’s about a young man chasing down a dream in the worst of times. Faolán Burke, son of a famous Irish warrior, is not a great catch. He should have inherited vast lands and the beautiful Castle Glencurragh. But the English lands confiscated the land, the castle of his father’s dreams was never built, and Faolán will try almost anything to make his lost heritage a reality.

In the opening scene, Faolán falls a bit short of his ideal. He’s abducting an heiress for his bride. There was no law against abduction at this time, and while I won’t say it was common, it did occur. Once abducted, women were considered soiled goods, the family could no longer negotiate a lucrative marriage settlement with a wealthy suitor, and usually would try to make the best of it with the family of the abductor.

In this case the heiress was under protection of an earl, and earls could generally exert their own law. So Faolán with his lady must run for cover until they have the protection and support of someone equal in power that can help negotiate the settlement.

But in 1634, the real world has changed. As the English plantation system spreads across the province of Munster, Irish families lose their homes to new English settlers. Lands that have been in their families for centuries now are given to English soldiers as rewards for service. Even castles, once both the bounty and protection of the strongest clans, now are vulnerable to the siege and cannon.

Moreover, knowledge and beliefs are changing. In the 17th century, Galileo and Newton founded modern science; Descartes began modern philosophy; Hobbes and John Locke started modern political theory. Science for the first time has greater influence than religion in decision-making. And people can own books. They become a symbol of wealth, and the bookshelf is invented to display them

Climatically, this was the middle of The Little Ice Age. The 1630s recorded great floods, widespread harvest failure, intense cold winters, wet and cold springs, and drought in summer.

Some scientists say even one degree of climate change can cause changes in human behavior. Faolán finds himself in the crossfire between the four most powerful—and irritable—men in Ireland, each with his own agenda.

THEMES:

Dreams: A young man trying to realize the dream of his father. Everyone has awakened from a dream so beautiful they want to hold onto it, but the longer they are awake the faster it recedes. From another perspective, many of us have seen the sacrifices our parents made and then tried to live their dream for them, only to realize later in life that it does not satisfy. We have to follow our own dreams.

Friendship: The relationship between best friends from childhood. Faolán interacts with his best friend Aengus O’Daly, who narrates the story. I am blessed to have known deep and lasting friendships of this kind that informed this story in ways I didn’t even realize until the end. I am truly grateful to my dear friends for that.

Hope. In great difficulty, when you have no power to change a circumstance that gives you pain, hope is what we rely on to get through, and it is the most human part of us.

Next: A Thorough Undoing

My next book picks up where this one ends, with events that occur between 1635 and 1641. Among English and Irish nobleman alike, hatred grows for the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, and they set out to destroy him. In service of the Earl of Clanricarde, Faolán is charged to find the evidence that will strip Wentworth of his power.

My next book picks up where this one ends, with events that occur between 1635 and 1641. Among English and Irish nobleman alike, hatred grows for the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, and they set out to destroy him. In service of the Earl of Clanricarde, Faolán is charged to find the evidence that will strip Wentworth of his power.

And now, a gentle request:

If you like what you read in The Prince of Glencurragh or any of my books, please take a moment to go online to Amazon, Goodreads, Barnes and Noble, or even Facebook, and write a quick review.

People buy books based on their friends’ recommendations, and book sales help authors pay for the editors, proofreaders and artists who help make the books the high quality you expect. Your words help authors with our words.

Thank you!

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

See all of my books and other information at

October 31, 2016

Tracking the Prince: Lismore Castle

Part 5 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See previous post links below.

Lismore Castle by Francis Wheatley (1747 – 1801) – British artist, Wikimedia creative commons

In The Prince of Glencurragh, the spectacular Lismore Castle in County Waterford is the setting for three emotionally-charged scenes. The grand drawing room and the ancient towers provide dramatic backdrops that help fortify the story.

Taking its name from “lis” meaning fort and “mor” meaning great, the castle is situated on the right bank of the River Blackwater in County Waterford. One story has it that when King James II visited the castle, he backed away from the grand window overlooking the river, startled by the sheer drop to the riverbank when the entrance to the castle is on  ground level. The window was ever-after called King James’s window.

ground level. The window was ever-after called King James’s window.

Sources differ as to the date of construction, but sometime between 1179 and 1185, Lismore was built on the site of the ancient abbey of Mochuda.

“This fine castle was originally founded by the Earl of Moreton, afterwards King John, in the year 1185, and is said to have been the last of three fortresses of the kind which he erected during his visit to Ireland. In four years afterwards it was taken by surprise and broken down by the Irish, who regarded with jealousy and fear the strong holds erected by the English to secure and enlarge their conquests.”

— LibraryIreland.com, the Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 43, April 20, 1833

The castle was later rebuilt as an Episcopal residence (one source says it belonged to the earls of Desmond), until in 1589 when the manor and lands were granted to Sir Walter Raleigh. Sir Walter fell from grace after the death of Queen Elizabeth, and sold the estate to Sir Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Cork. Raleigh was later executed by King James to appease the Spanish, who saw Raleigh as a plundering pirate.

Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork

Lord Cork made extensive improvements to the castle for use as his primary residence. Outbuildings were added, and interiors embellished with fretwork plaster ceilings, tapestry hangings, embroidered silks and velvet.

“The first door-way is called the riding-house, from its being originally built to accommodate two horsemen, who mounted guard, and for whose reception there were two spaces which are still visible under the archway. The riding-house is the entrance into a long avenue shaded by magnificent trees, and flanked with high stone walls; this leads to another doorway, the keep or grand entrance into the square of the castle. Over the gate are the arms of the first Earl of Cork, with the motto, “God’s providence is our inheritance.”

— LibraryIreland.com, the Dublin Penny Journal

Some of the outbuildings were destroyed in the rebellion of 1641 when the castle was closely besieged by 5,000 Irish, and defended by Lord Broghill, the earl’s third son.

Some of the outbuildings were destroyed in the rebellion of 1641 when the castle was closely besieged by 5,000 Irish, and defended by Lord Broghill, the earl’s third son.

The Cavendish family acquired the castle in 1753 when the daughter and heiress of the 4th Earl of Cork, Lady Charlotte Boyle, married William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, who became Prime Minister of Great Britain & Ireland. The 9th Duke, Lord Charles Cavendish, married Adele Astaire, the sister and former dancing partner of Fred Astaire.

Lismore is now an exclusive accommodation and event venue, and even offers culinary packages. The famous gardens are open to the pubic. The upper garden is a 17th-century walled garden, also briefly featured in my book.

Thanks to C.L. Adams’s Castles of Ireland, LibraryIreland.com, celticcastles.com, lismorecastle.com.

Read other posts in the series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh has won the Royal Palm Literary Award for historical fiction. It is a story of 17th century Ireland, in a time of sweeping change prior to the great rebellion of 1641. Available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

See all of my books and sign up for my newsletter (published only 3 or 4 times a year) at nancyblanton.com