Peter Hitchens's Blog, page 255

November 2, 2013

Massie Attack

When I first saw Alex Massie’s latest posting, I quickly forgot about it. It did not once cause me so much as to scratch my chin in doubt, or to seek new figures, or to re-examine my arguments. It was just a bog-standard reiteration of the drug liberalisers’ creed, larded with some mild personal abuse. Then I was amazed to find that various people were praising it as some sort of masterful, crushing response.

Two of these are individuals who have made public *personal* attacks on me in the past, but who (while willing to wound me when among friends who will applaud this) have always avoided any sort of actual direct debate with me on the disagreements between us. In one case, the person involved (who picked a fight with me, wholly unprovoked, for no reason on our first meeting) has ignored repeated invitations to make his case on my blog. I have no idea who the others are, but I am used to the fact that the drug liberalisation lobby resent the continued existence of any voice which opposes them, and besiege such voices with abuse and denigration. The person publicly and intemperately attacked me at an Orwell Prize event, and the nature of that attack (and my temperate response to it) can be found on YouTube by those with reasonable detective powers. When they have seen it, they may begin to understand his interest here.

Then there is the fact that Mr Massie bears an honoured name, and his articles appear on the website of a respected magazine which has long been a very important part of British conservative journalism, and to which I sometimes contribute. So I sit here in a Sydney Hotel, composing a reply. I do not expect this reply to have any impact upon Mr Massie. That would be to flatter him. I write it for the many people in the world, especially the young, who are perplexed and distressed by the social and cultural pressures placed on them, to take drugs; and who are puzzled by the blatant official lying about the state’s true attitude towards technically illegal drugs.

This may seem ungenerous to Mr Massie. And there has to be a basic generosity in debate, as I often state , a willingness to accept that you may in fact have something to learn from your opponent, a willingness to accept that he or she is fully human and has motives which he or she at least believes to be good. If you really think your opponent is a deluded idiot, then of course you have no need to challenge his arguments.

But this is so lacking in his approach that I, desiring to be forgiving, find it very hard to do so until he has shown some sign that he recognises this sort of thing is wrong and that (as John Henry Newman put it in a long-ago debate with Charles Kingsley) it breaches the laws of war and can be described as ‘Poisoning the Wells’.

What do I mean? Take this passage : ‘ I rather regret suggesting Mr Hitchens is a nitwit. That was unnecessary. I do think his argument – impeccably sincere as it may be – runs towards nincompoopery but since we all hold beliefs other people consider idiotic we might do well, at least occasionally, to recall the usefulness of treating the man and the ball as separate concerns.’

In this he abuses me while pretending not to. I know nothing about Mr Massie at all. The patronising attribution of ‘sincerity’(which being translated means ‘poor deluded old booby’), the ‘I don’t want to say he’s a nitwit and a nincompoop and an idiot, but of course he is’, is typical of the faintly grubby technique known as ‘willing to wound, but fearing to strike.’ This is what you get for saying that your opponent is ‘undoubtedly intelligent’, as I did.

I know nothing of Mr Massie and I suspect he knows very little of me. I suspect that (as do many of my critics) he thinks he knows more than he does, and has seldom felt the need to find out if his prejudices match the facts. I would imagine that, in the world he inhabits, dismissing people such as me is guaranteed to produce a warm snigger of collusion and shared disapproval.

Yet he seems to take it personally when I set out the truth about the British state’s attitude to ostensibly illegal drugs, which he purports to believe is one of stern and draconian prohibition. I am said to have said that the ‘war on drugs' is a ‘figment of *his* imagination’. Oh, not just his. Nothing personal, Mr Massie. You are wrong, but the emphasis in this statement is on the word ‘wrong’, not on the word ‘you’. It isn’t all about you, or about me. Actually, it’s about a grave peril, complacently encouraged by fashionable opinion, to a number of young men and women, who as I write this may be taking terrible risks with their futures, and the futures of those who love them. And Mr Massie might consider that his articles may be used by such people as reassurance that that they are not in fact running any danger at all. In this, I do plainly criticise an *action* performed by Mr Massie. But I don’t attack him as a human being.

Then we move on the terms of debate, as set by Mr Massie. He says :

‘The essence of his argument is that, look matey, there is no such thing as a War on Drugs. The evidence for this assertion – and I am afraid it is merely an assertion unbuttressed by the facts it sorely needs – is that the War on Drugs is not prosecuted nearly as vigorously as Peter Hitchens thinks it should be.’

This is extraordinary. I did not set out all my evidence in a brief blog posting (though of course I gave a taste of it there). My evidence is set out in some detail in a book. ‘The War We Never Fought’,(Bloomsbury, 2012) to which he should resort if he wishes to know my full argument. That is why people write books – because they seek to state a case in full. Has Mr Massie read my book? I do not think so.

For if he had, he simply could not assert much of what follows.

He takes this passage(by me)

‘[O]ur decriminalisation is covert and unacknowledged, because international treaties and political necessity currently make open decriminalisation or legislation difficult; also that it is directed mainly at the use and consumption of drugs, not at their importation, cultivation or sale. So far as I can discover, and figures on this are difficult to obtain, the weakening of the cannabis possession laws has been followed by a weakening of the possession laws as applied to Cocaine and Heroin, and also to a softening of sentencing for supply (and the introduction of ‘compounding’ as a way of letting off people importing small amounts of illegal drugs into this country).’

And promptly completely misunderstands it, thus:

‘But how weak are these laws? In recent years we have seen Cannabis reclassified as a Class B drug, Khat classified as a Class C substance, raw magic mushrooms categorised as a Class A substance, Ketamine given a Class C status and Methamphetamine upgraded to a Class A product. In addition other, more exotic or less well-known substances such as Methotexamine have been added to the long list of prohibited drugs.

Since, as best I can tell, no drug of any sort or kind has fallen off the list of prohibited substances and, actually, several more have been added to the catalogue it is perverse to argue that this represents a climate of de facto decriminalisation.’

Oh dear.

By ‘weakening of laws’, I do not simply mean the dilution of statute penalties for drug possession, though this has been in progress for 40 years, as detailed in my book.

I mainly mean the increasing unwillingness of police to arrest and charge, or of courts to apply anything but the lowest level of penalty for possession for cannabis in particular. It is incontrovertible that this has taken place, and my book describes in detail how this has happened.

My point is therefore that the law continues to exist in paper, but is not enforced in fact. Is this a very difficult concept to grasp? I think not. Would it be hard to disprove, if my claim were false? I do not think so. The existence (and widespread use) of the ‘Cannabis Warning’, for instance, is a living, operational proof of my point.

There is, of course a, point at which this process moves beyond statistics. It is well known and undisputed that the police, encumbered by the Codes of Practice of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, increasingly dread having to make arrests because of the tangle of bureaucracy which then ensues. It is also undisputed that the Crown Prosecution Service, which long ago supplanted the police in deciding whether cases should go to court, decides not to prosecute huge numbers of cases which the police, even in this era, think worthy of an arrest.

Once an offence (and shoplifting is another example of this) is almost guaranteed to be met with a shrug by the Crown Prosecution Service and the Courts, the police will try not to pursue it unless they are absolutely forced to, by the blatancy of the individual offence, or the repeated nature of it. Cannabis possession is now such an offence. The police can and do simply ignore it ( and have been observed doing so by journalists) at pro-cannabis demonstrations in central London, at such events as the Notting Hill carnival and at the major rock festivals. Who seriously denies this? Does Mr Massie? Worse, I have repeatedly been told by haggard parents (in prosperous southern towns and less comfortable northern ones) of drugs being on open sale at their children’s state schools, and of the police’s unwillingness to take action to stop this. The remarkable thing is that, despite trying so hard to ignore it, the authorities are still occasionally forced to act or (as I point out) sometimes use the existence of the law to arrest people who they are in fact pursuing for other less easily proven, offences. But that does not change the general position. Cannabis is a de facto decriminalised drug. The strength of the laws on the statute book has no meaning if those laws are not enforced. As I say, this is not a hard concept to grasp.

Mr Massie, and his supporters, do not fail to grasp it because there is anything wrong with their minds, or because they are ‘nincompoops’ or ‘nitwits’. They fail to grasp it for the reason which has, down all the ages, been the strongest force of deception known to man. *They do not want to know*.

For instance the sleight-of-hand in the following passage (the mistaking of paper penalties for actual ones), is an almost exact repeat of a similar claim made in a famous pamphlet by Peter Lilley MP, which I rebut in detail in my book. Nobody who had read my book (or who was paying attention at all) could simply repeat this dud argument and non-response as if it were some kind of decisive blow:

‘Moreover the maximum penalties for both possession and supply of drugs remain severe. Seven years for possessing Class A substances (life for supplying them), five for Class B (14 years for supply) and two years imprisonment for possessing Class C drugs (14 years for supplying them). Doubtless Peter Hitchens would complain that maximum sentences are not imposed with sufficient frequency. And, of course, convicts are often released from jail before they have served their full sentence. Nevertheless, these tariffs are hardly evidence of undue leniency even if, as Hitchens might claim, the full force of the law is invoked too rarely.’

I don’t ‘claim’ this. I state it as a demonstrable fact. Does Mr Massie dispute it? Let us see his figures on the legions of people flung into dungeons for cannabis possession by ruthless authority, if he has any.

Nor is it a question of rarity. The facts show that extreme leniency is standard.

My precise point, and I repeat it here for anyone still in doubt, is that paper penalties are maintained, to abide by international treaties and to reassure conservative voters, but that these mean nothing when they are not enforced. By the way, the person who initially alerted me to this was the late Steve Abrams, the most skilful and dogged campaigner for the weakening of cannabis laws in this country, progenitor of the famous ‘Times’ advertisement of 1967, signed by the Beatles, which called for cannabis decriminalisation. It is Mr Abrams’s thesis which (with grateful acknowledgement) I have made more widely known in my book. Mr Abrams’s purpose was different from mine. He was annoyed at the way in which some drug liberalisers seemed to have forgotten or minimised his role in making cannabis a decriminalised drug in this country, and refused to recognise the extent of his success. Shortly before he died, I sent Mr Abrams my manuscript and was pleased to learn that he broadly agreed with my analysis. Not all drug liberalisers close their minds to the facts. Some undoubtedly do.

The rest of his posting is consists of the usual exaggerations of my arguments, those exaggerations then being correctly dismissed as such, and this being presented as a refutation of my case. I believe there’s a technical term for this sort of thing.

Then there’s lots of unresponsive stuff which does not in fact address my simple point, that the possession and use of drugs in this country has been effectively decriminalised and that the state, pursues an illogical and futile sham war, whose only purpose is to fulfil inescapable treaty obligations and to soothe the remaining moral conservatives in the electorate that something is being done when in fact it isn’t. Meanwhile, young men and women are starting on courses of action from which they might be deterred, courses of action which will ruin their lives and the lives of those who love them.

And the rudest thing I can say about Mr Massie and his friends is that their words and actions are making these tragedies more likely. I do hope that they will one day understand this, and seek, in the time remaining to them, to make amends for this terrible, selfish mistake.

Mr Massie was responding to my response to him, here, which is still a pretty definitive statement of the point, and which I doubt most of my critics have read with any care

This was a response to an unprovoked assault on me which Mr Massie posted here

Mr Massie’s latest attack upon me is here

October 28, 2013

Travel Advisory

October 26, 2013

Today's children have much more to fear than a belt from Dad, Cilla

This is Peter Hitchens' Mail On Sunday column  We live in a censored society, made all the worse because we gag our own mouths.

We live in a censored society, made all the worse because we gag our own mouths.

Since I first heard it decades ago, I have loved the ‘Liverpool Lullaby’, a rather good poem about a mother’s exasperated love for her troublesome son.

A lot of other people love it, too. It should be taught in schools instead of that boneless, rhymeless twaddle they call poetry these days.

Not many songs get released as a B-side single and then become more popular than the A-side.

It is hugely evocative. The opening lines – ‘Oh, you are a mucky kid, dirty as a dustbin lid’ – summon up a whole way of life: a bare room with a small coal fire, surrounded by a twilit landscape of terraced streets stretching down towards the docks on a long-ago Saturday evening. Dad’s at the pub. There’s not much food in the house.

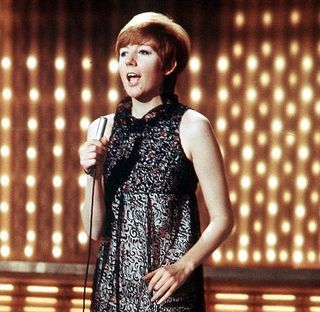

Cilla Black recorded it in the 1960s (it was written in 1959) and still gets asked to sing it. Except that it’s now been watered down.

In a recent TV appearance, she replaced the mother’s repeated warning to the boy that he’ll ‘gerra belt from your dad’ with the feeble ‘you’ll get told off by your dad’.

I asked the song’s author about this. He is Stan Kelly-Bootle (a Cambridge-educated mathematician and computer whizz) and – while he quite understands why Cilla Black did what she did in these PC days – he says: ‘The phrase “you’ll get a belt from your dad” is hyperbole typical of Liverpool and means nothing more than “wait till your father gets home”.

‘It’s the same as saying, “I’ll kill him” when someone has misbehaved big time. It doesn’t mean you’re going to organise a drive-by shooting, at least not in the UK.

It’s just an expression and I don’t think that you should read modern attitudes to child abuse into a song that was written over 50 years ago.’

Quite. If Cilla Black really wants to update the Lullaby, she should go much, much further. There’s no room here for a long debate about smacking. But we do so many worse things now that we’re enlightened.

Today’s deprived child is probably zonked on Ritalin (and his mother on Prozac). He’s probably not that mucky, as he sits all day and all night in front of the TV instead of running wild. The dirty dustbin has been replaced by a battery of Eric Pickles-sized eco-containers.

And while the poor have more money than they did, they have many more perils, too. I wonder what rhymes with ‘pay-day-loan’? ‘Methadone’, perhaps?

But saddest of all, the Lullaby’s boozy, wastrel Dad has vanished from view in hundreds of thousands of homes. He won’t be coming home because he was never there in the first place.

The man who might turn up instead is much more worrying, the current boyfriend who loathes any child that isn’t his own. You’ll get much worse than a belt from him.

And then, not long afterwards, there’ll be the social worker who can’t see anything wrong. Sing a song about that, would you, Cilla?

********************************************************

It is worth pondering how some forms of ‘discrimination’ are still all right, and others not. Killing baby girls because they aren’t boys is one.

Now here’s another. Aric Sigman, a psychologist and biologist, points out that women who raise their own children can be sneered at without fear as ‘self-lobotomised’, servile and sexually unattractive.

Dr Sigman has spotted the modern Stalin-Hitler pact that unites huge, supposedly incompatible forces against this defenceless group.

‘The older feminism, liberal-Left feminism, has ended up a strange bedfellow with Right-wing capitalism.’ Almost there. But why does he think capitalism is ‘Right-wing’? If Leftism pays, that’s fine.

The ONLY way to protect the innocent

Politicians who know the case for capital punishment is unanswerable will often wriggle out of supporting it by a trick.

They will ask anxiously: ‘What about hanging an innocent person by mistake? How could we have that on our conscience?’

Leave aside the fact that every murder victim is innocent, and that many now dead would be alive if we still executed heinous murderers.

Note that nearly once a year, an innocent person is killed by a convicted murderer given a ‘life’ sentence but freed to kill again.

The latest such horror is the death of Graham Buck, a valorous and noble man who went to the aid of a neighbour.

That neighbour was being attacked by Ian McLoughlin.

McLoughlin, now back in prison, will, with a bit of luck, stay there until he is no danger to anyone.

But you might ask why he was free, or even alive.

In 1984, a court somehow ruled that it was ‘manslaughter’ after McLoughlin killed Len Delgatty, smashing his skull seven times with a hammer, cramming his body upside down into a cupboard and ransacking the house for money.

He was out of prison in five years. The judge pretended to sentence him to serve ten. Even that was reduced to eight years on appeal.

Can these judges sleep? Three years after his release, he was sent to prison for ‘life’ for stabbing Peter Halls to death.

Then some genius allowed him out on day release, so freeing him to murder Mr Buck.

Innocent deaths all over the place.

And I promise there will be more. But none of them causes our compassionate, conscience-stricken politicians to regret their abolition of the gallows, or reconsider it. Funny, that.

*******************************************************

Have you noticed how mainstream advertisements are turning political? While waiting to see that puzzling but exciting film Captain Phillips, I endured two bank commercials.

In one, a young man was seeking a home loan because he didn’t like his granny’s ‘Right-wing views’.

In another we were shown two female twins, with contrasting lives but the same sort of debit card. One had a husband.

The other had a lesbian girlfriend. What are these commercials really selling?

******************************************************

For reasons that will become clear, I can’t use names here. But, as I too often do, I was investigating claims of police indifference (and worse) to the plight of an individual besieged by louts.

A spokesman for the force involved asked to ‘go on background’, that is, to say things that couldn’t be quoted.

This publicly salaried official then began to smear the complainer, saying there were ‘issues about mental health’.

When I didn’t immediately swallow this poison, and asked for details, the mouthpiece turned hostile and refused to say more.

The blackening of Andrew Mitchell is a huge issue because the police in general are out of control. Small, local forces on foot patrol are the answer, not helmet cameras.

If you want to comment on Peter Hitchens, click on Comments and scroll down

October 25, 2013

Do try a bit of Deep Thought, Michael

There was an interesting contrast today between my personal mailbox and Twitter, the one full of mainly supportive comments about my appearance on the BBC’s ‘Question Time’ and the other seething with loathing. Well, both are obviously selective and there’s no great surprise there.

Nor is there much surprise about the Twitter Mob (never out of the top drawer, intellectually) seeing some sort of contradiction in my condemning the recent mass immigration into this country, and recommending those young enough to do so to emigrate from this country while they still can.

(Why the urgency? The accelerating depreciation of the Pound Sterling will make relocation increasingly difficult. The current inflation rate, alleged to be around 3% a year but probably higher in reality, plus the almost complete suppression of interest, means that in 15 years or so the value of any savings or property you have will be nearly halved, or at least much diminished in realisable saleable value. I am by no means sure that property prices, outside the immediate London commuter belt or even within it, can sustain their current levels either. In many desirable destination countries, these effects will not be matched. Emigration without some savings and the ability to buy or rent a home while seeking work is pretty hard, and (see below) not to be encouraged in most cases. It’s also the case that British educational qualifications , once respected, will increasingly be seen for what they are, devalued paper).

But I was disappointed when my old acquaintance Michael Rosen, whom I remember as an ornament of the radical movement at Oxford (I was a townie, he a student) in the late 1960s, and whom I have always rather liked as a person, tweeted as follows ; ‘Peter Hitchens #bbcqt : deep thinker said, UK ruined because of immigration,therefore people should leave. (ie become an immigrant!)’

Oh, come on, Michael. Do act like the grown-up you are. You might try thinking a little more deeply than this shallow crowd-pleasing jeering. First of all, I was careful, as I always am, to use the specific phrase ‘Mass Immigration’ . Why? Because immigration on the scale encouraged by New Labour (see many articles featuring the amazing revelations of the former Blairite apparatchik Andrew Neather ,for example http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/neather-andrew/ ) and not seriously hampered by the Cameroons, cannot be properly absorbed.

Nothing on this scale has happened in this country before. Even before it began, we were already having grave problems integrating our Muslim minorities, especially in the Pennine towns, and the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Eastern Europeans has transformed many areas and overloaded many public services (of the kind that people such as Mr Rosen are keen on) . Accusations of racial bigotry against those who are worried by this would be false anyway. But the fact that the migrants are predominantly pinko-grey Europeans makes it impossible to claim that objections to this migration are motivated by irrational skin-based dislike, a lie that has been useful in the past in heading off any objections to large-scale arrivals. The difference is (as it always has been) to do with language and culture. And the real question has always been – shall the arrivals adapt themselves to us, or shall we adapt ourselves to them?

For those who don’t much like this country anyway, the choice is plain. They will demand multiculturalism because they see it as a useful tool for dismantling the British monoculture, conservative, Christian, monarchist, puritanical, which they wish to get rid of and have wanted to get rid of for decades. For those who do like this country, it’s equally plain. Immigration must be kept to levels small enough to ensure that the migrants are encouraged to integrate and to become British, the best way of ensuring harmony and of maintaining the British nation state, the largest form of social and political organisation in which it is possible to be effectively unselfish. This is the real quarrel and, when it is stated in this way, it is hard for the revolutionaries to win it. That is why they almost always seek to smear their opponents as bigots.

It is also material. Many migrants are, thanks to their position, willing to work for far less than the locals, and to live in much more basic conditions while they do so. This, inevitably, has the greatest impact on those working for low wages, the sort of people Mr Rosen seemed to be worried about back in those Sixties days. Of course Mr Neather and people like him see great advantages in this pool of labour.

He explained how immigration had been ‘highly positive’ for ‘middle-class Londoners’. He wrote: ‘It’s not simply a question of foreign nannies, cleaners and gardeners – although frankly it’s hard to see how the capital could function without them.’

He was even franker: ‘But this wave of immigration has enriched us much more than that. A large part of London’s attraction is its cosmopolitan nature.

It is so much more international now than, say, 15 years ago, and so much more heterogeneous than most of the provinces, that it’s pretty much unimaginable for us to go back.’

I suspect that is true. Our borders are held wide open by our EU membership, and will shortly be even more open, as more ‘accession’ countries join the EU, and as the EU becomes increasingly unable to patrol its Mediterranean coastline, or its porous border with Turkey.

So the left have won. The country has been transformed. Those who loved it as it was have lost the country they loved. They must either live in a place which is no longer the country they grew up in, and adapt with varying degrees of willingness to a different world, or seek their fortunes elsewhere. Since the new multicultural Britain is also a low-wage nation, heavily crowded in its most prosperous area, plagued with poor schools, bad and expensive transport, failing medical services, rising living costs, rising levels of casual violence and disorder (masked by fiddled government figures which fool only the rich and insulated) and increasing government incompetence, any young person must , it seems to me, at least consider the possibility of moving elsewhere.

Why should this be contradictory? Nothing in the above passage involved any condemnation of *migrants* as such. Who blames them for seeking to better themselves by coming here (even though many of them are bound to be disappointed)? Certainly not I. I have never written a word of criticism of them, and hope I never shall. Having lived abroad, in rather comfortable circumstances, and uprooted my life to do so (with far more help and ease than most of them could dream of) I have at least some inkling of the courage and determination they must have needed. It is the people who have encouraged them to come, without having any idea how to handle the changes they bring, who draw my wrath.

Were I to migrate to any other country, I would adapt myself to its laws and customs, learn its language as well as I could, and ensure that my children did so too. I hope I would continue to remember my old home, and see to it that my children knew of their heritage, but I would recognise that, by accepting the protection of a differnet state and its laws, I owed that state my undivided loyalty, and a duty to become as fully integrated as possible, as soon as possible. I would see it as my duty to do so, and would be amazed and disappointed if my new host country did not insist on this.

I would expect them to apply serious immigration laws and checks, and would abide patiently by them. I would expect to start at the bottom of whatever trade or profession I followed (this is why I say that only the young are really free to do this). I would be amazed if (for instance) Canada suddenly announced that any British person could immediately go to live and work in Canada, provided he or she could get there.

Now, can anyone – having read the above - tell me what is the contradiction between opposing mass immigration into this country, and advocating emigration to other countries? It’s only there if you don’t think, Michael.

An Interview with Australia's Radio National, and Professor Stevens Again

Some of you may wish to listen to an interview I gave recently to Australia’s ABC Radio National (I’m planning to speak on the non-existent ‘war against drugs’ in Sydney on 3rd November)

You may download the audio of this programme by visiting this address

Meanwhile, Professor Stevens has replied, sort of, to my two responses to him.

http://www.talkingdrugs.org/peter-hitchens%E2-fantasy-based-drug-policy

I have personally invited him to come here and do so, and I repeat the invitation publicly, but when he does I hope he can do better than this unresponsive reiteration, which is close to the ad hominem. The British Crime Survey on which he seeks to rely is a grandiose opinion poll, notorious for the way it leaves out the young. Even if it didn’t, any survey which required named and traceable individuals to tell an official body if they used an illegal drug must be open to doubt (the same would apply to surveys in schools).

Many jurisdictions , for political or treaty reasons, maintain the outward appearance of stringent laws against drugs. An ignorant or propagandist outsider could believe or pretend that this was the real position. But in practice, they do not apply them consistently or generally. So to complain that they ae ineffectual is rather to miss the point.

He says ‘I can only reply that if I were to respond to every accusation, contradiction, exaggeration, distortion, supposition and tendentious insinuation in his writings on this subject, it would try the patience of the most fascinated reader.’

OK then, let us have a specific example of one ‘exaggeration’, and one ‘distortion’ (the other things he accuses me of are not open to objective proof and are abuse dressed up as debate. These two, more or less, might be objectively demonstrable). An exaggeration would of course involve a material overstatement of a measurable objective fact. A distortion would involve a twisting of a measurable objective fact, to such an extent that it misled the reader.

October 23, 2013

Why the Long Haul to Keele was Worth It

Last night I completed my national anti-drugs tour, with a debate at the University of Keele, near the Potteries in Staffordshire. I feel as if I have been arguing about this subject for a year without stopping, though in fact, when I tot it up, I’ve also debated about, or spoken about, national politics, foreign policy, mass immigration, the Tory Party and of course the Ancient of Days during the same period. But mostly it has been drugs, from the Henley Festival a year ago to the Cheltenham Festival earlier this month, via Salford, Oxford, Bristol (in both of which places I debated with Howard Marks), Exeter and Canterbury, to Keele.

I’d never been to this beautifully situated campus before. It was rather unfashionable in the early days of the Plate-Glass universities (York, Sussex, Essex, Kent at Canterbury, East Anglia, Lancaster) set up in the late 60s thanks to the Robbins Report. It had pre-dated them. It lacked their modernistic glamour and their cathedral city picturesqueness. I now realise that this expansion was the last flowering of the grammar schools, wafting their meritocratic products into the higher reaches of the establishment in unprecedented (and unrepeated) numbers. Is this why they were also so radical? And why the generations which have followed have always been by comparison, a bit of a walk on the mild side? Someone ought to look onto it, but it had better not be me, because any book I write from now on will be buried in obloquy. The only book the British chattering classes want me to write is my Prison Diaries.

Keele is close to the Five Towns of the Potteries made famous by Arnold Bennett, an author I’ve still not properly explored (though I unhesitatingly recommend ‘The Old Wives’ Tale’, the only one of his books I have read). Like so much of the industrial Britain I took for granted in my childhood, it has been completely transformed. Much evil has been swept away, in terms of cramped and badly-built houses, filthy air and class distinction. But with it has gone a whole industry of superb pottery, often beautiful and providing tens of thousands of families with an honest and secure living, and so underpinning a happy and sociable way of life. I used my senile person’s bus pass to travel to the campus from Stoke-on-Trent railway station – itself a superb triumph of Mock Jacobean architecture, beautifully done in brick and stone (what a change from the ubiquitous concrete of the modern age) and kept in remarkably good condition. This expansive, generous and confident building was obviously meant to express the area’s prosperity and success when it was built. I keenly felt the absence of a Top Hat and side-whiskers as I scurried scruffily through its majestic portals. I quite often have this sensation, in the more confident and better-preserved relics of an older, harder, more formal Britain, of being a barbarian scuttling about amid the ruins of a half-understood lost civilisation.

The top deck of my bus allowed me to admire what seemed to be the chief industries of the new Potteries - pound shops, takeaways, hairdressers, a hydroponic emporium, but (unusually in this sort of landscape) no visible nail bars. I also saw no mosques, and no niquabs, though there were a few hijabs in view. No doubt there are glossy out-of-town malls, and pleasant suburbs which I did not see, and I think I spotted a huge new football stadium on the outskirts, but as so often I gained the impression of a place in which almost nothing was now being used for its original purpose. This has, for some time, seemed to sum up modern Britain. The problem is, what is its new purpose?

Well, we’ll see.

But after a few miles of this we climbed a hill, providing a lovely, tawny autumnal view across the Potteries to the hills beyond, and wound into the campus itself. In the midst of it sits the old Keele Hall (an unfortunate name, if you have any naval knowledge), an enjoyable 19th-century monstrosity which lies heavily on the earth. Beyond lies a beautiful chestnut avenue, presumably a leftover from a former house, which would be quite enchanting if it were not assailed by the endless obliterating sigh of tyres and the unsettling growl of engines from a nearby motorway. And there are mature woods, and a lake as well. I wish I’d had more time to explore them.

I’ll say little about the debate, which has been held here dozens of times, except to give my most sincere thanks to Grant and Gareth (who also gave me two fine loaves of properly-baked bread) .They manfully stood in for our opponents, who weren’t there. One of the missing was Peter Reynolds, whose car broke down on the way, and who provides the speech he would have delivered here http://www.clear-uk.org/what-peter-hitchens-missed/ . The other missing speaker’s absence remains a mystery to me, so I’ll not go into it.

I’ve spent a lot of time on replying to pro-liberalisation blogs in the past few weeks, so I’ll leave it to readers to work out what I would have said in reply to Mr Reynolds.

I and my ally in the fight against drugs, David Raynes, both thought that the best thing to do was to have as full and as courteous a debate as we could. With inexperienced volunteer debaters against us (who rose very well to the occasion) there was no point in gladiatorial techniques. I think we both sensed that the mood of the meeting was heavily against our position from the start, and concentrated on sowing seeds of doubt. The curious voting procedure, in which members of the audience wrote down ‘before’ and ‘after’ views on slips of paper, did show a very slight shift towards our position, but as it also seemed to show that some members of the audience had dematerialised or been abducted by aliens between votes, I am not sure what to make of it.

I asked, as I had at Canterbury, how many members of the audience had used illegal drugs and (as at Canterbury) the great majority of those present unhesitatingly put up their hands. How anyone, seeing these displays, of blithe law-breaking and blithe willingness to admit to it, could continue to pretend that we lived under a draconian prohibition regime, I simply do not know. My hope at all these occasions is that David or I may have planted, in the minds even of one person, a doubt about the wisdom of taking a drug which is far more dangerous than its reputation would suggest. Just one such doubt would justify all the long hours in the train, the late return home and the lost evening, all the preparation, all the repetitive and unresponsive prosing of the drugs lobby, all the glasses of tepid water

I’ll append a couple of responses to this post. I see that a certain persistent and dedicated critic, wholly lacking in generosity, has now (by an amazingly convoluted pathway from the issue of the MMR being imposed on two children) got on to male infant circumcision. I’ll leave it to the supporters of that practice to defend it. I’m mildly against it, but I defend their freedom to do it, because two of the World’s major faiths make it a requirement, and attacks on it from outside those faiths seem to me to be indirect attacks on followers of those religions, who in one case are also an ethnic group. If people want to do that, then let them do it directly, not crabwise and sneakily. Oddly enough, in my childhood, many American and British doctors recommended circumcision for medical reasons (reasons which have also been advanced by religious defenders of the operation) , and it became quite widespread among non-Jews and non-Muslims (as did the equally fashionable procedures of tonsillectomy and appendectomy). That seems to have faded now.

But if two parents disagree about male circumcision, then no judge should dare to instruct that the operation goes ahead, especially if the delay means that the child involved will be aware of what he is to undergo (non-infant circumcision seems to me to be absolutely and unquestionably a matter for the proposed circumcisee, and nobody else). The only proper action by the law should be to maintain the status quo, and say that as long as the parents differed, no action should be taken. That is an almost exact parallel with my view of the MMR matter.

But then my generosity-free critic employs his technique of subtle, imperceptible twisting of what I have said, which will work on those who for one reason or another don’t see my response. Does he begin to understand the contempt I have for his behaviour? If he wishes to provoke me into reacting, he has of course succeeded, but does he realise why and how? He knows I regard his contributions with scorn ( as I do) and is presumably annoyed by the fact that I ignore them. He could overcome this easily, by posting items which were written for the purpose of intelligent, generous debate. Instead, it appears that he seeks to provoke me into a response. He has succeeded that far. I hope he likes the response even less than he likes the silence.

Here he is ‘But what about Mr Hitchens's view that parents should be free to beat... sorry, 'discipline' their children? After all, it involves an actual physical assault on the child that they can't simply renounce when they get older, the risks are obvious, the benefits to the child are more than questionable and it takes a huge leap of faith to believe that just because someone has produced some offspring they can be trusted to enforce the violence fairly.’

Well, it is quite true that I think parents should be free to smack their children if they wish, and not to smack them if they prefer. The word ‘smack’ is quite clear in its meaning, but in case of any doubt it means a light blow with the palm of an open hand. I am amazed to find myself living in a culture where this harmless form of discipline, the open-handed smack, is looked upon as barbaric and brutal, on the verge of crime, while the drugging of healthy children, and the permanent and irreversible alteration of their brains and bodies with potent psychotropics is looked on as normal, encouraged by teachers, social workers and doctors, and generously subsidised by the state. I also think that ‘just because someone has produced some offspring’ is an extraordinary dismissal of the immense responsibility, to protect, provide, guard, cherish,teach, guide and nurture which descends on the shoulders of the parent, never to depart.

How on earth did we get here? Nobody was talking about smacking, nor circumcision, nor about religion. Yet Mr Hunter has managed to insert both subjects into a discussion about a court-enforced immunisation against the wishes of one parent and ,it seems, both the childrne involved (an event which I should have thought would have provoked some sceptical thought even in the most complacent mind). In reply to another nuisance contributor, if ‘PTSD’ has no objective existence, wouldn’t it be rather idle to propose a uniform treatment for all the different forms of suffering and behaviour now included under this suspect umbrella? And these people wonder why I prefer to ignore them.

October 21, 2013

Nigel Farage, Drugs and a Major Reason for not liking UKIP

I am grateful to Lewis Taylor for drawing this exchange to my attention (It’s in an interview of Nigel Farage, link below, done by the same University of York student who recently interviewed me)

Interviewer: 'We spoke to Mail on Sunday columnist Peter Hitchens last month and he wanted to know where UKIP stands and where you yourself Nigel Farage stand on the legalisation of drugs.

Nigel Farage: 'Hitchens and I disagree on this fundamentally. UKIP as a party takes the same view as Hitchens, that we haven't really enforced the law properly and that we have to get generally tougher. My own view is different. I think the war on drugs was lost many years ago. Hitchens will say it was never fought, I know. But we are where we are and drugs are now openly available not just in the streets of London, but in little hamlets and on the North Cornish coast. This isn't even an epidemic it's endemic. The history with prohibition as we saw with alcohol in America is disastrous. I feel a huge amount of crime, they call it petty crime but its not so petty if its your Grandmother is it? Who's been bashed over the head and had her handbag taken and I feel the more we can do to take drugs and the whole drugs industry out of the hands of the racketeers the better.’

You can watch it all here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3dNKx30AW4 (begins approx. 9.56)

Readers might like to compare this with an earlier statement by Mr Farage on the subject on the BBC, on 2nd April 2010, recounted here.

http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/2010/04/what-did-nigel-farage-say-about-drugs.html

On that occasion, he said :’ ‘I have a feeling that prohibition in this whole area simply isn't working. Every year we say that we are going to fight the war on drugs harder than we have fought it the year before. And I think this is one of those areas of life, and, whilst people may find this distasteful, I think we need a proper full Royal Commission on this whole area of drugs to investigate whether perhaps life might be better for millions of people living on council estates that are dominated by the drugs dealers, that are dominated by the crime that surrounds, the money that people raise, to get these drugs, let's find out through a Royal Commission whether perhaps we should decriminalise drugs, whether we should license them, license the users, and sell them at Boots - because frankly if you add up the costs of drugs to society the big problem is the fact that they're criminal and everything that goes with that. And I think there is an argument that says if we decriminalised it we would make the lives of millions of people far better than they are today.’

He went on to add, when challenged by the Labour Cabinet minister Peter Hain: ‘The drugs problem, the cost of policing it, the costs of prisons, gets worse every year.’

When Mr Hain said that he (Mr Farage) was talking about a drugs free-for-all, Mr Farage (in my view not very accurately) retorted that he hadn't said that, but that he had called for a Royal Commission to investigate it. It seems clear from his words that he would hope for that Commission to produce a particular outcome.

He then returned to his argument, saying: ‘If you examine the percentage of crime, the amount of police time, the amount of court time and the amount of people in prison and you add it all up, drugs are costing this country £50 to £70 billion a year - all because it's a criminal activity. And I would argue that when the ban on Mephedrone comes in, the big winners are the drug dealers.

‘The policy's failing. More and more people are taking drugs, the cost goes up every year, we are losing the war on drugs, let's face up to that.’

When the programme's chairman, Jonathan Dimbleby then pointed out that some police officers believed decriminalisation would ease the problem, Mr Farage appeared to me to say ‘absolutely’ in approving tones.

Some Replies to Contributors - MMR, monarchy and drugs

Some responses to comments. First, to Mr Falls, who writes : Having read Neil McKeganey's Controversies in Drug Policy and Practice and Theodore Dalrymple's Romancing Opiates, I am baffled as to how Mr Hitchens feels they corroborate his semantic argument about addiction.’

To which I reply that it is the facts in their books, rather than any views expressed by the authors, which back up my point.

Mr Falls correctly says : ‘Dalrymple's book uses the term addiction and addict throughout he does not doubt the existence of addiction rather he states that withdrawal in his clinical experience is not as severe as many believe and that literature from De Quincey to Irvine Welsh has romanticised the severity. This has resulted in a conventional wisdom and a situation where literature rather than medical reality informs drug treatment. He also doubts the efficacy of substitute treatment and criticises it's expense. McKeganey also thinks addiction exists but criticises the biological reductionist view seeing social deprivation as a contributory factor. He is strongly critical of methadone and subutex substitution because of its cost and its ineffectiveness. He proposes residential abstinence based treatment rather than harm reduction which exacerbates the problem. So neither doubt the existence of addiction. Dalrymple's doubts the severity of withdrawal whilst both are critical of harm reduction.’

I go further than them perhaps because it is my job to do so. The clear conclusion of Dr Dalrymple’s account, for me, is that the idea of ‘addiction’ as an insurmountable affliction, a medical condition which can only be alleviated by treatment and even then may persist or return, is false.

I don’t at all blame Dr Dalrymple for not actually saying directly that ‘addiction’ doesn’t exist, even though his description of ‘addicts’ shows that this is the case. Like Professor McKeganey, his work brings (or brought ) him into daily contact with the modern ‘treatment’ establishment, for whom the idea of personal responsibility is actively horrifying, and the idea of ‘addiction’ therefore an article of faith. They will have learned long ago that there is no practical point in engaging with these fanatics. I’ve never asked either man about this. My hostility to the ideas of ‘treatment’ and ‘addiction’ is not shared by any of my allies in the campaign to retain and strengthen our drug laws, and I just put up with that. They are practical people seeking to attain practical ends. I am a voice crying in the wilderness making a moral case. I expect my allies have done what I did in the past over many similar matters, and simply not allowed their minds to range beyond the borders of what was conventionally accepted. It is a perfectly normal thing to do. I’ve just given it up.

Anyone thinking of criticising the absurd concept of ‘addiction’ as widely accepted in our society, only needs to watch the hurricane of abuse and screeching which I have received for stating this obvious truth. They would find, as I do, that the advocates of ‘addiction’ will happily use it to mean one thing ( an insurmountable, overpowering physical affliction which is not the sufferer’s fault and from which he cannot escape unaided, if at all) when they are demanding funds for its ‘treatment’ and as something quite different ( a far more nuanced condition which can be conquered by the sufferer under certain circumstances and may even be his own responsibility) when they encounter informed critics.

The two are obviously wholly contradictory, and a universe which accepts the first as true cannot also accept the second as true. But the one that brings in the funds, and these days ensures the employment of substantial numbers of (wholly disinterested) persons is the one that maintains it is a physical insurmountable condition, entirely absolving its victims from personal responsibility.

Once again I commend readers to my discussion of the matter with ‘Citizen Sane’ which can be found here http://bit.ly/GzI61T. He too greeted my position with scorn at the beginning, but was open-minded enough to concede it.

My purpose is a moral one. I seek to point out when falsehoods are being told, and false ideas followed. This is not because I hope to influence current events - though I often find that my ideas do actually become current, and even modish, years after I first encounter derision for expressing them – my advocacy of bicycling as a civilised modern method of transport for instance, drew me nothing but mockery from colleagues, as well as lectures about the (undoubted) dangers back in the 1970s. Now I can’t move in London for the legions of cyclists.

It is because I think someone just has to tell the truth about what is going on. The existence or non-existence of ‘addiction’ is a moral question, like so many others. And my moral position rests on a profoundly unfashionable belief in personal responsibility for our own actions.

What is noticeable about so many of the defenders of ‘addiction’ is the way they simply cannot cope with any challenge to it. They act and speak as if it is self-evidently true. This is almost invariably the response of believers to challenges to their faith. It is self -evidently true that water will wet us and fire will burn ( and in my view it is self-evidently that fear is a powerful motive, and that therefore effective and consistent punishment of actions influences the doing of them). But the existence of ‘addiction’ is not in that category. It only survives because it is conventional wisdom, which is almost invariably wrong, and almost invariably accepted by almost everybody.

‘Baz’ like many others, misses the point of the MMR judgement.

The injection into a human bloodstream of a vaccine is an invasive, irreversible physical assault on the human body of an innocent person. The person compelled to undergo this assault is not guilty of any offence deserving punishment - which I would accept, though ‘Baz’ probably wouldn’t, might under some circumstances justify a lawfully-imposed physical penalty .

‘Baz’ may think that there is ‘no logical reason’ to refuse the MMR, but ‘Baz’ needs to understand that in a free society others may have different views, and this should be left to them. His opinion is not an objective fact, and certainly cannot be the basis for ordering physical assaults on innocent person.

‘Damiana’ writes ; ‘Odd that adults inflicting an injection on a child is a no-no, yet adults inflicting religion on a child (in order to be a Girl Guide) is not. The difference, of course, is perpetuating health as opposed to perpetuating a religious tradition that not all humans share in the first place. ‘

This seems to me to be a wholly false comparison, which only a mind furiously prejudiced against religion could make. The raising of a child in a religious faith involves no invasive physical assault, and in any case takes place in the family, a fortress of freedom against absolute state power, whose independence any free person should support. The child brought up in a faith is free to reject that faith when it attains the age of reason, and indeed is better equipped to reject it than a person who does not even know what it is, and so can have no real opinion of it. If, as ‘Damiana’ presumably believes, religious faith is self-evidently transparent drivel, then the child will be *more* likely to reject it if he or she encounters it in its full force, than if he or she is merely mildly aware of it as something other people do.

The arguments (many times rehearsed here) about the MMR make it clear that there are very different views about a) the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing the dangers of measles b) the certainty we can have over the safety of such vaccines in all cases. The other simple point is that it is wholly irreversible, and cannot be undone if its effects turn out to be damaging, or if future knowledge shows that it is harmful. There is also the issue of the social contract bargain suggested by the immunisers, in which we have some sort of duty to risk our children for the sake of the Blessed NHS and the (alleged) Higher Good. As I say, in a People’s Republic such ideas are law. But in a free society, they are not. I am merely pointing out that the MMR zealots are not, in fact, lovers of freedom, but rather sympathisers with the other thing. I understand that they don’t like this being pointed out, but in that case they should either decide that they like the strong state and dislike liberty, and be honest about it, or change their views.

A Mr ‘Edmund Blackadder’ asks :’ On the question of the Royal Train, does Mr Hitchens not think that at a time when food banks are on the increase, it does look like a case of 'let them eat cake, when the well heeled and well subsidised royals are now getting a ruddy refurbished train to themselves?’

No, Mr Hitchens doesn’t. The idea that that monarchy is a huge public charge is laughable. I am interested and perplexed by the growth of food banks, but their existence suggests to me that there are detailed failures in the benefits system, which need to be fixed, not that it lacks money in general. Nobody should go without food if their families or they have no way of providing for themselves. The train, as others have pointed out, is not especially luxurious, and many Presidents are far more costly and luxury-lapped than our monarchy.

The bizarre idea that republics are in some way *automatically* more free and fair than monarchies persists against all the evidence. It is quite possible to be a monarchy and to be free, in fact in most of the Anglosphere, and in Scandinavia, constitutional monarchy has been a most successful way of ensuring liberty under the law, and of affirming the sovereignty of free peoples under laws chosen by themselves. Many Republics seek to emulate many of its characteristics (Ireland, I think, being one of them). The USA is an 18th-century monarchy in which the monarch, instead of inheriting, is picked by billionaire donors every four years. France is, likewise an elective monarchy. Germany is an interesting experiment which has yet to run its course, but s currently running into trouble because its deliberately indecisive, consensual constitution cannot cope with several major issues, from nuclear power to the Euro. Switzerland is the only Republic I can think of with as much popular sovereignty as the British monarchy provides. And then we have all those other Republics which are or were neither free nor fair – the Republic of South Africa, under the apartheid regime, the German Democratic Republic, the Chilean Republic under Pinochet, etc etc etc. It’s all about thinking, instead of repeating what you’ve heard on the TV or picked up at PSHE, as usual.

I agree that a fully nationalised police force is precisely what we don’t want, and is probably being planned. That's why we need to call for more local police forces, as we used to have before Roy Jenkins closed them down.

Mr Falconer posts : ‘Many of the states within the USA have in place the most draconian penalties for all forms of drug use, where a second offence of possession of cannabis results in a prison sentence, only avoided in the first place by strict judicial. supervision regimes. The result has been that the so-called "land of the free", the USA, with only five percent of the world's population, has over twenty-five percent of its prisoners, currently numbering over two million.’

I need much more detail here. An impression is given by this arrangement of words, but is it the right one? I do know that the drug laws in much of the USA are at least as lax as our own *in practice* (see the case of Jared Loughner, known to the authorities as a long-term cannabis user, never prosecuted for the offence, let alone imprisoned) , though the route of ‘medical marijuana’ has been the main way in which this has been achieved. But perhaps he could list a) these states, and b) explain what he means by ‘only avoided in the first place by strict judicial supervision’ . What is avoided? What does this ‘supervision’ actually involve? and c) can he please explain how he jumps from these statements to the figure of two million prisoners. How many of these prisoners have actually been incarcerated (rather than, say, given suspended sentences never served) for *simple possession of cannabis, with no intent to sell, on a first or second offence, and for nothing else*? Breakdown by state would aid comparison with the figures on drug use, or at least arrests, which we would then need to seek.

And a few more responses to responses

My goodness, the microscopic ingenuity of some of my critics. Take this, from Mr 'B':'Peter Hitchens still maintains that addiction does not exist; that each individual has the will power to resist the urge to take an action by which he might be tempted. However, he only seems to use such an argument when talking about drug or alcohol addiction. Contrast this with his views on television which he considers to be harmful and which he wishes had never been invented. In an article posted on this blog on 21/11/11, the reason he gives for this standpoint is that "very few humans have the will to resist it". If they do not have the will to resist television, something extraneous to their bodies, why does he imagine that they have the will to resist taking drugs, something which they ingest into their bodies and which Mr Hitchens has conceded can damage the brain? '

Human will is not a fixed quantity, but, like muscular strength, something that can be strengthened by use and weakened by disuse. If people are encouraged to take responsibility for their actions, they will develop the will to do so. From their earliest childhoods, western children are left in front of TV sets by absent or lazy adults and accustomed to the passive state this engenders. Damage will be done, but they can be rescued from it, and indeed trained to rescue themselves. It's the same with drugs. The best thing with both is not to start at all, and deterrent punishment is good for preventing drug abuse. But I don't think we could make TV-watching, a crime, or even the dumping of children in front of TV a crime (though it is one) . In any case, the 'withdrawal symptoms' of supposedly addictive drugs are hugely exaggerated by fiction, movies and myth. It's probably harder to stop watching TV. But it's possible to stop doing both, if you want to.

Christopher Charles must grasp that many of the greatest human beings who ever lived came out of poverty and deprivation a thousand times worse than anything in modern Britain or the USA. How then can such poverty and deprivation be advanced as an excuse for the wilful crime of drug abuse? It just won't do. It's the propaganda of the tax and spend lobby (who always cream off a large share of that spending for their own fat salaries, and for whom even the riches of the 21st century are 'poverty'. For if 'poverty' ever ended, so would their fat salaries) .

Mr Falls makes similar excuses, which likewise serve the vast and well-funded 'treatment' industry and and its appendages ' Drugs and addiction are a symptom of Broken Britain not a cause, concealing the underlying issues of unemployment, poor education, poverty, alienation and despair that incompetent Westminster politicians have caused. ' They are neither a symptom nor a cause. They are immoral, criminal acts done by people controlled neither by conscience nor by law. If people have morals, there are fewer bad deeds. if they won't have morals, then they must have fear instead. Where would-be criminals fear the law, they do not break it. But where there are neither morals nor law, chaos follows.

Those who argue against morals and law, and excuse bad behaviour, are Apostles of Chaos, and will not be able to complain when it comes, kicking, yelling swearing and screaming, to their front doors. The rest of us will blame them.

'Baz' lectures me ;'One more time Peter, the father gave his consent for his children to be inoculated. Why do you think that a parent shouldn't be able to make decisions about the welfare of their children? The complication in this case was that the mother disagreed. It went to court, and the court found in favour of the father'

Well, one more time, Mr 'Baz', examine the real issue of how a free country can force this thing on three people who (as far as we know) don't want it, including the two who will undergo it, because a fourth does, who will not undergo it. As he later rightly points out, the parents are divided on the issue, which raises all kinds of problems. But in general, where a deliberative body (such as the parents in a family) cannot reach agreement, the chairman (or Judge) must cast his vote in favour of the status quo. You cannot base an action on a vote which shows an even division on its merits.

He adds 'since there is no scientific evidence against MMR.'

Others differ about this. I understand there have been judgements in other jurisdictions which have suggested it may have problems, and I refer him to Vivienne Parry's interesting point in the Observer in July 2007 ( she is a supporter of the MMR) :' "There's a small risk with all vaccines. No-one has ever said that any vaccine is completely without side effects. But we have to decide whether the benefits outweigh the risks. If we had measles, it would kill lots of children. If you have a vaccine, it will damage some children, but a very small number.'

I think that's the calculation, though as it happens I think the MMR zealots hugely exaggerate the dangers of measles. And what if your child is one of the 'some'? The State won't care, and may wish to deny any connection, using all its force and wealth to humiliate and belittle the persons involved, as States do. But you will care, quite a lot .

He continues:'The case is very much the same as the Neon Roberts case, when his mother tried to stop him receiving radiotherapy. Would you describe radiotherapy as a "serious assault"? I'm guessing not, as it wouldn't allow you to make ill-informed comments about MMR. '

Is it much the same? No, it's not the same at all, not remotely, and I'm shocked and rather revolted at the crudity and twisting involved in the suggestion. Neon Roberts was seriously ill, and the radiotherapy was a rational treatment for that illness, given the current state of medical knowledge These two children are not ill at all, and if they were, the injection wouldn't cure or treat them. Even in cases of serious illness, people (or their parents) do have to sign consent forms for invasive surgery, in free countries.

Oh, and 'Baz' can be excused for not realising this, but I have recent personal experience of the effects of radiotherapy on a close relative, and having seen them, I can easily see why a mother would hesitate over allowing such a thing to happen to a beloved child. It is a very powerful and severe process, searing and painful long after it has taken place. I would hesitate to undergo it myself, however bad the alternative.

Oh, and 'Paul P', with every appearance of not realising he is saying anything silly, posts : 'I think Mr Farage is taking a pragmatic position and making pragmatic points'

Does he really? Who'd have thought it? I am sorry to be reduced to sarcasm, but surely it is the only reasonable reponse to platitude posing as profundity.

Mr 'P' continues :'The market for recreational drugs is now simply too big, and as history shows with parallel issues, Prohibition in America as Mr Farage cites, the market will sooner or later prevail.'

When will the contributors who ceaselessly cite 'Prohibition' look it up and find out what actually happened? How many times have I dealt with this? Yet it has never even gone in one ear, let alone out of the other. He discovered this wonderful argument, years ago, and nothing is going to shift him from it, let alone facts.

'Prohibition' never even attempted to ban consumption or possession of alcohol. Tiny resources were devoted to enforcement of its bans on manufacture, transport and sale. The USA, unlike Britain, has vast unpatrolled borders, immense unwatchable coastlines and a huge interior. Alcohol had previously not only been legal, but in regular use by tens of millions. The German and Italian minorities, respectable, law-abiding and hard-working, both regarded the Act as a prejudiced assault on their ways of life. There is, simply, no comparison.

Mr 'P' intones that 'Casualties, such as there inevitably will be in numbers deemed too small to count, will be tolerated.'

By whom? Not, I think, by the elderly, impoverished parents forced by an inadequate health service to nurse their ruined, hopeless, broken adult chidlren, seduced by the stupid propganda of the 'drugs are safe' lobby. *They* will not tolerate it. They will hate and resent it, or those who made it more likely, and they will be right.

Mr 'P', perhaps immune from such a threat, is jolly generous to offer to 'tolerate' it on their behalf, but I doubt if he will be offering himself (I'd conscript him if it were up to me, on the grounds of invincible smug self-satisfaction) to man the locked wards through the long, howling weekends, or provide respite care.

He says, grandly 'That's why we have an NHS.'

Is it so? Does he have any idea of the hopeless inadequacy of our mental hospitals even now? How much worse will that be if the liberalisers get their way?

He concludes' Mr Hitchens' campaign will I fear come to be seen more and more as an idiosyncratic out-of-stepness with popular opinion, the sort of idiosyncrasy one sees from time to time announcing the coming end of the world on sandwich boards.'

Yes, I suspect he is right. But when did the fact that something *is* so come to mean that it *ought* to be so? What logic, or moral calculus, leads to this conclusion? That is, I accept, the sort of society we are. But whose fault will that be? Mine, for telling the truth? Or his, for sneering at me for doing so?

He concludes, bizarrely:' It is very regrettable because I think Mr Hitchens' underpinning moral reasoning is sound, that a drugged-up society moves irrevocably closer with every fix to an acquiescent state of political somnambulance.'

What will his role be in making this happen?

October 20, 2013

My Second Reply to Professor Stevens

This is the second part of my response to a blog published by Professor Alex Stevens, of the University of Kent at Canterbury, and available here.

http://www.talkingdrugs.org/alex-stevens/evidence-versus-morality-debating-drugs-with-peter-hitchens

In my first response I dealt with some simple factual points, and about what I regard as unconscious misrepresentations of my case by Professor Stevens. I stress that I think he himself is the main person deceived by these distortions.

This is why he does not actually address my factual case – that the British state has informally abandoned attempts to interdict demand for cannabis - with any great verve or originality. Howard Marks is a much better spokesman for the drug liberalisation cause, not least because he’s clear and open about what he wants, and because he listens to what I say.

I noted in my previous post how the Professor had simply missed my point on an important issue. I shall need to do so again, in a separate case, below. The fact that an intelligent person does this is always interesting and educative.

Now I turn to the curious dichotomy he seeks to establish – between evidence and morality. The implication is that, as my case is moral at heart - which it is – I have allowed my moral beliefs to influence my handling of facts. Have I? If so, where and when? Amazingly in an academic, he criticises my evidence as being ‘selective’. The Professor must know that all evidence is by its nature selective to an extent, since it is beyond the physical capacity of human beings – even full-time academic researchers with secretaries and, perhaps, the help of graduate students - to assemble *all* the evidence on any given subject.

Selectivity is only wrong if it deliberately leaves out facts which contradict the writer’s case, or deliberately exaggerates or misrepresents those which support it. If he can point to any instances of this, will he please do so? If not, can he please stop saying this?

My book, I should say here, does not purport to be an academic study. It is much better-written and much more to the point than most such things. It is clearly and proudly polemical. But it is also correct. It tells (with evidence and supporting quotation in some quantity) the much-neglected truth about the enforcement of laws against the possession of some drugs in England and Wales since 1971. This truth is unwelcome to those who like to claim that this country groans under the weight of a cruel prohibition regime, as they ceaselessly do. Why they claim this is for them to say. I can only point out that the claim , perhaps coincidentally, serves the interests mainly of those who seek to weaken our drug possession laws still further, and whose ultimate objective is presumably that we should have no such laws at all. Whether those who serve those interests know what they are doing, only they can say.

Now, here’s an instance of the Professor, who is so concerned about ‘evidence’, getting things wrong because he hears what he wants to hear. We suffer here from the absence ( so far as I know ) of any recording of the Canterbury debate. If anyone has one, can I please listen to it? But let’s take this passage :

‘Hitchens may be right that there is no biological diagnostic test for drug dependence. But his main argument against cannabis is that it produces schizophrenia. Both schizophrenia and drug dependence are diagnosed on the basis of the behaviour and the self-reported experiences of the patient. Neither of them can be detected by blood test or biopsy (although some neuroscientists claim that both conditions are visible in brain scans). If you’re going to say that addicts choose to use drugs, you might as well say that schizophrenics choose to have delusions. But that would not support an argument on the tragic effects of cannabis.’

Now, I first got involved in this discussion some years ago. It has been a long, steep learning process. Journalists ( and perhaps Professors) suffer from the old problem of conventional wisdom. They think they know all kinds of things until they study them. Then they find out that they don't know about them at all. Luckily, 40 years of journalism have taught me to examine everything with a scepticism that most people find annoying and pessimistic, but which I regard as essential.

And I freely admit that, when I began to discuss it, I assumed (as most people do) that classifications such as ‘Schizophrenia’ had an objective meaning. Actually, it was my interest in two separate controversies, over ‘ADHD’ and ‘Dyslexia’ that led me to the discovery that this wasn’t necessarily so, and to my introduction to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association and its strange history. I then learned even more about the vagueness of (ancient and modern) psychiatric medical diagnoses by looking into the controversy surrounding ‘Clinical Depression’ and the prescription of SSRI tablets.

Similarly, I have come to question the universal acceptance of the concept of ‘addiction’ as an insurmountable physical affliction rather than as what it is - a grandiose description of a failure of will, intended to relieve the so-called ‘addict’ of personal responsibility for that failure. And I have learned that, like all heresy, this is shocking to most people. This is a society which largely rejects personal responsibility and is unpleasantly surprised when anyone suggest that it might in fact still exist.

Since that point, I have simply ceased to use the term ‘Schizophrenia’ , except in the course of explaining that it is a shape-shifter and a moveable feast, along with almost all mental illnesses. I have certainly long ceased to suggest direct causal links between cannabis and any mental illness, including ‘Schizophrenia’. I have stuck to what we have, which is a very worrying and very strong correlation between cannabis and mental illness. I tend to speak at length about the case of Henry Cockburn to make this point. I also take the view that we are at the same stage we were at with cigarettes 60 years ago, in that the correlation is severe and striking but the direct evidence of causation is lacking. (By the way, we’re told it’s all anecdotal. Here’s a recent such anecdote

http://www.dailyecho.co.uk/news/10732162.Motorway_plunge_victim_was_high_on_cannabis/?ref=rss

…which is of course as anecdotal as all get out, especially the rather terrible detail about how the poor child was identified. But there are a lot of these anecdotes in our local papers, and at some point anecdotes might begin to add up to evidence, if anyone selective enough were to try to connect them).

I have used the term ‘mental illness’. If Professor Stevens had read my book with any care, or even listened to what I said that night, I think he would know this.

Yet Professor Stevens seems to have heard me specifically linking cannabis to Schizophrenia in Canterbury that night. Well, it’s possible he heard me correctly, and I don’t like to directly contradict anyone on facts, as it’s potentially rude. But in the light of the above, how likely is it that I did so? I am well aware of the inconsistency he tries to pin on me. If ‘Addiction’ isn’t objectively measurable, how can ‘Schizophrenia be?

That, by the way, is as far as the contradiction goes. ‘Addiction’ and ‘Schizophrenia’ share very few characteristics apart from the difficulty of objectively establishing their presence in the human frame.

I would normally doubt the logical and intellectual powers of anyone who said ‘If you’re going to say that addicts choose to use drugs, you might as well say that schizophrenics choose to have delusions.’.

But, as this is a Professor speaking, I owe it to him to take this comparison seriously. On ‘Addiction’ I do urge him to read Theodore Dalrymple’s witty and informed work ‘Romancing Opiates –Pharmacological Lies and the Addiction Bureaucracy’ . Dr Dalrymple was for many years a prison psychiatrist and encountered ‘addicts ‘ in large numbers ( a brief taste of his experience can be read here http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-476208/Heroin-addiction-isnt-illness--stop-spending-millions-treating-it.html by the open-minded few (note in particular his dismissal of ‘withdrawal symptoms’, and the ease with which his patients stopped using the drug when it suited them to do so). I also repeat my link to this discussion I had with another person who initially believed my dismissal of ‘addiction’ was outrageous http://bit.ly/GzI61T

But the point here is that nobody is forced to take the drugs which are generally supposed to be ‘addictive’. Nobody ‘catches’ ‘addiction’. Habitual use of heroin or crack cocaine has to be deliberately, doggedly pursued, by repeated ingestion or absorption (often involving wilful and actively painful and unpleasant self-harm).

Now, one of the things about severe mental illness, such as that which falls within the accepted current diagnosis of ‘Schizophrenia’, is that its victims are generally struck down without warning by symptoms they did nothing to bring about. Its causes are, I think, largely unknown in most cases. Heredity, grievous emotional stress and physical injury have all been blamed. To compare the undesired onset of such a terrible affliction with the deliberate ingestion of an illegal drug known by all to be dangerous is a logical absurdity which would be comical if it weren’t also rather nasty. And this from a Professor!

I would add that if Establishment persons such as him accepted (and I do not know if he does, for he tends not to respond to arguments about this, but suspect he doesn’t) that there is a significant correlation between illness and cannabis use, then the position would alter slightly.